July 11, 2024

Farshid Moussavi’s Open-ended Architecture Comes to the U.S.

“Architectural practice is nonlinear,” Moussavi reflects. “The project evolves along the way—and constantly evolves. There is no way an architect has all the answers on day one, when a project takes six to ten years to come to fruition.”

Prior to establishing FMA, Moussavi—an elected member ofLondon’s Royal Academysince 2015, a professor in practice atHarvard Graduate School of Design (GSD),and a recipient of the 2022 Jane Drew Prize for women in architecture—ran a collaborative practice called Foreign Office Architects (FOA). Earlier works completed in this partnership, like theYokohama International Port Terminal(2002), reveal both a striking material sophistication and a deep understanding of the aliveness of architecture, qualities that have flourished in her later practice

Speaking over Zoom from her studio in London, Moussavi describes this aliveness in two phases—the design process, in which “chaotic flows of desire” like financial constraints, client expectations, and social conditions must be mapped together; and the “micropolitics” that play out after each project’s completion. Moussavi defines these as nuanced and evolving relationships between users and the building.

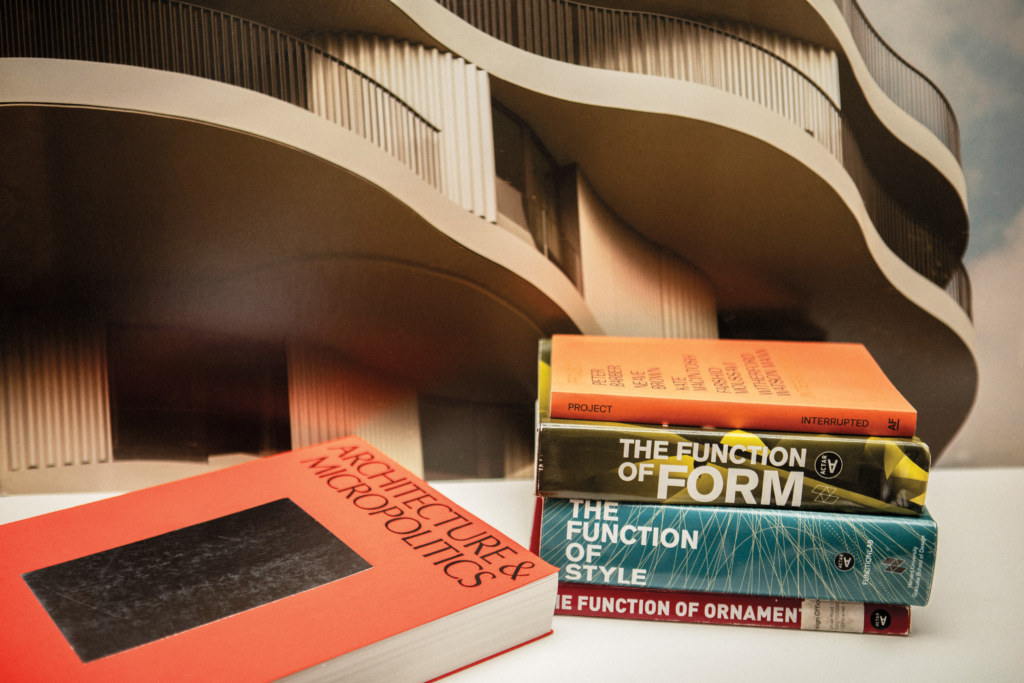

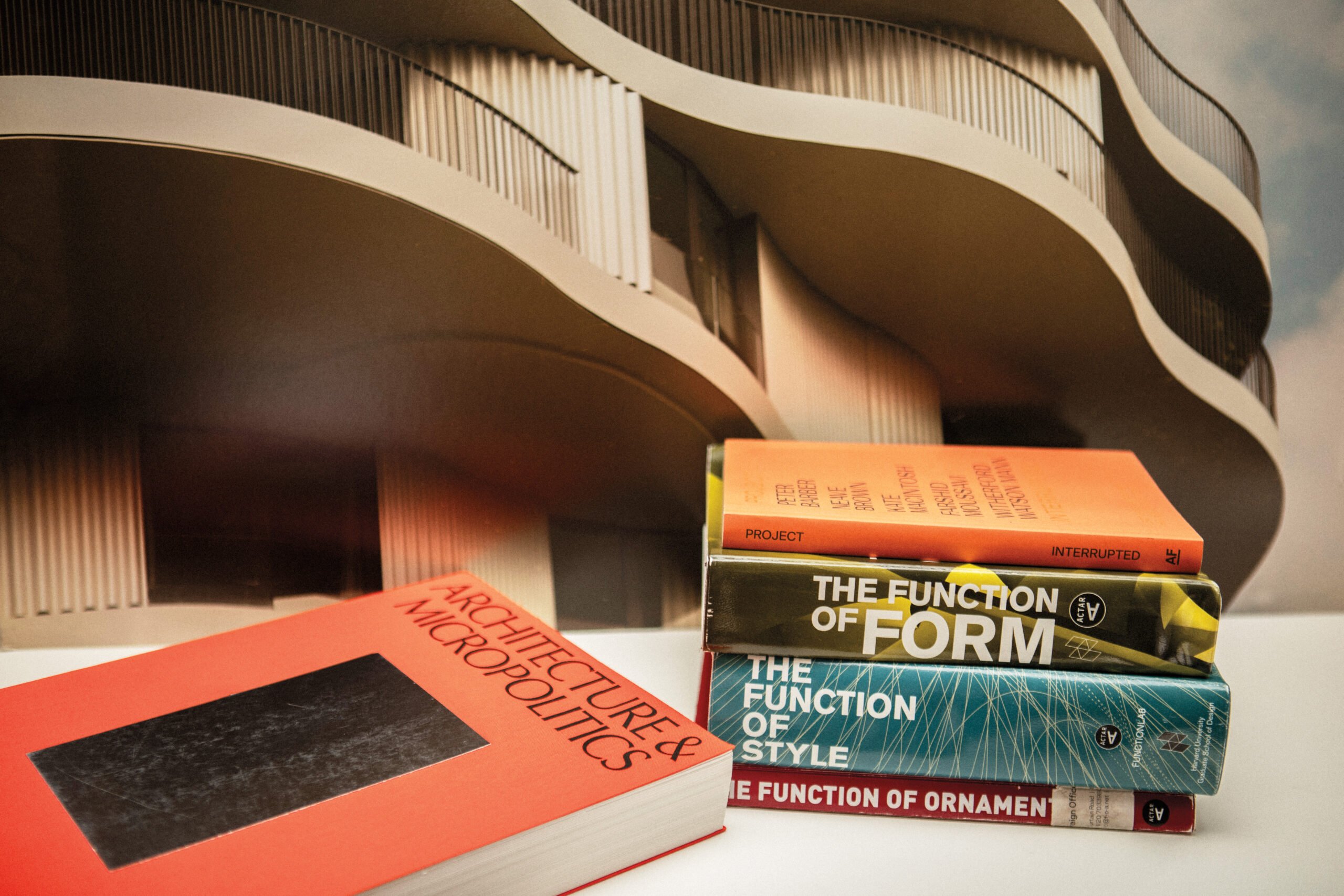

The architect’s latest publication—an almost-600-page monograph titledArchitecture & Micropolitics(2022)—highlights four key projects pursued over the past decade of practice, and includes a brief text by French philosopher Jacques Rancière, who examines the subversive role of the user in FMA’s projects. Moussavi, for her part, draws her work into dialogue with the rhizomatic theories of Deleuze and Guattari, as well as the open-ended wanderings of experimental literature like that of Walter Benjamin. FMA projects channel theArcades Project,for sure, but are also reminiscent of the player-led lore-making of an open-world videogame.

A Building as an Open-ended and Multiauthored System

When considering a building as an open-ended, multiauthored system, multiple clichés from the history of architecture can be offloaded. First up: the building as a product of the so-called “master architect.” If architecture can be understood as an assemblage of “actants” —defined by Moussavi as the architect, building, and user—it can also be seen as something of a hive mind. For Moussavi, this distributed agency of the building is precisely the point. “Architectural practice is nonlinear,” Moussavi reflects. “The project evolves along the way—and constantly evolves. There is no way an architect has all the answers on day one, when a project takes six to ten years to come to fruition.”

While one can read certain values across FMA projects—flexibility, transparency, scalelessness, stacking, and reflectivity among them—these qualities shape-shift across each building. Hence there is no trademark “style” that is intrinsically FMA-coded; it’s less about a signature material output than a mood. For Moussavi, this affective capacity of the architecture is at the heart of a building’s micropolitics, which can be more intricately defined as the small-scale encounters or details of a building that trigger necessarily unpredictable reactions from its users, who in turn extend the life of the building by interpreting and utilizing it in their own ways.

In that spirit, it seems fitting to embark on a nonlinear tour through some of Moussavi’s architectural worlds, beginning with two French housing projects completed a year apart:Îlot 19 in La Défense(2016) andLa Folie Divine in Toulouse(2017). Îlot 19 appears like a great slab of glass and dark metal; horizontal screen-laden loggias and open balconies run the length of the building, alternating across its 11 floors, which are composed of mixed private and student accommodation, retail units, and public space. Its four lobbies are shared among all its diverse residents; each apartment’s unique layout allows for continuous customization as the residents’ needs change. Meanwhile, the bright La Folie Divine—its curvaceous design defined by rippling corrugated aluminum—likewise blurs indoor and outdoor space across its nine floors. The building offers its residents panoramic, unobstructed views of its garden surrounds from generous balconies lined with billowing curtains. Both projects advocate for a kind of universal luxury, with modifiable floor plans that enable residents to develop their own worlds while nestled inside a larger built ecosystem.

Gleaming like a gnarled block of silica, theCleveland Museum,completed in 2012, shores up haphazardly on its axial boulevard as if dropped from outer space. The building’s prismlike form is composed of two rhomboids and six triangles; the acrobatic gemstone contorts from a hexagonal base to a rectangular rooftop. Clad in black metal paneling, with thin strips of diagonal windows running along its flank like a rib cage, the building’s reflective surface dynamically picks up its surroundings.

“The building’s cladding was originally going to be a champagne-gold aluminum,” Moussavi shares. “But a prompt from a donor at a meeting triggered a big color change some four years into the project.” The museum’s final plate and form—a reflective black-mirror stainless steel exterior, with a royal-blue metal gallery overhang interior and an origami-like twisted staircase hovering above the lobby—ditch the white-cube formalism endemic to museum design for something much more interesting.

Moussavi Turns Micropolitics into Macroscale

FMA’s first project in the United States—the Ismaili Center in Houston,initiated in 2021 and due to complete in 2025—offers a whopping 150,000 square feet for the architect to put micropolitics into macroscale practice. Commissioned by His Highness the Aga Khan, the imam of Ismailism, and conceived as an “ambassador building” to bring Islamic faith into dialogue with other cultures and communities, it is also the first Ismaili center in this country. Moussavi’s design features intricate stone tile cladding with Persian detailing, a large veranda supported by thin columns, and three interior atria. Set within ten acres of gardens designed byNelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects,and theDLR Groupserving as executive architect and engineer of record providing architecture, MEP/FP engineering, acoustics, audiovisual, lighting, and theatrical services. The building offers a combination of mixed-use social spaces alongside more private pockets including a Jamatkhana for worship. “The building is designed to be very porous and open, responding to the local ecology and weather patterns of Texas,” explains Moussavi. “The larger the project, the more can be done with its micropolitics.”

In addition to FMA, Moussavi maintains a robust pedagogical and research practice. This includes FunctionLab, the research arm of FMA, and a housing-themed studio at Harvard GSD since 2017. Prior to her new monograph, Moussavi publishedThe Function of Ornament(2006),The Function of Form(2009), andThe Function of Style(2014)—a trilogy of texts that analyze architectural affects and propose new means of conceptualizing the flows of material, ideology, and agency within built systems. FunctionLab unites Moussavi’s material and theoretical practice, enabling the built projects to feed into research and vice versa, ouroboros-like, tending to an ever-evolving ecosystem of ideas.

Moussavi’s keen attention to the sense-making of sensory experience, matched by the architect’s commitment to framing architecture as an ongoing and collaborative act, distinguishes her approach and output from many contemporary practitioners. For Moussavi, it’s never been about imprinting the practice on the project, but each project shaping the practice according to its needs. “When the architect goes, the building remains,” reflects Moussavi. “The key is always keeping the system open.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to:[email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

Sustainability Is the New Luxury

Conscious choices can lead to peace of mind, and there is so much beauty to be found in regenerative materials.

Viewpoints

How the Built Environment Evolves with the Times

METROPOLIS’s Summer 2024 issue explores the function of buildings and the forces that shape them.

Products

5 Architectural Products for Higher Education Projects

From mass timber to twisted sunshades, these new materials are positioned to be first choices on university campuses.