Abstract

Plasmodium knowlesiis an intracellular malaria parasite whose natural vertebrate host isMacaca fascicularis(the ‘kra’ monkey); however, it is now increasingly recognized as a significant cause of human malaria, particularly in southeast Asia1,2.Plasmodium knowlesiwas the first malaria parasite species in which antigenic variation was demonstrated3,and it has a close phylogenetic relationship toPlasmodium vivax4,the second most important species of human malaria parasite (reviewed in ref.4). Despite their relatedness, there are important phenotypic differences between them, such as host blood cell preference, absence of a dormant liver stage or ‘hypnozoite’ inP. knowlesi,and length of the asexual cycle (reviewed in ref.4). Here we present an analysis of theP. knowlesi(H strain, Pk1(A+) clone5) nuclear genome sequence. This is the first monkey malaria parasite genome to be described, and it provides an opportunity for comparison with the recently completedP. vivaxgenome4and other sequencedPlasmodiumgenomes6,7,8.In contrast to otherPlasmodiumgenomes, putative variant antigen families are dispersed throughout the genome and are associated with intrachromosomal telomere repeats. One of these families, the KIRs9,contains sequences that collectively match over one-half of the host CD99 extracellular domain, which may represent an unusual form of molecular mimicry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

TheP. knowlesigenome sequence was produced by whole-genome shotgun sequencing to eightfold coverage, with targeted gap closure and finishing (Supplementary Table 1). The 23.5-megabase (Mb) nuclear genome is composed of 14 chromosomes and contains the expected complement of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) genes with known function (Supplementary Table 2) and a large number of novel structured ncRNA candidate genes (Supplementary Figs 1–5andSupplementary Tables 3 and 4). The presumed centromeres are similar to those found in otherPlasmodiumspecies4,6,and are positionally conserved within regions sharing synteny withP.vivax(seeFig. 1of ref.4). The overall G+C base composition is 37.5%. A total of 5,188 protein-encoding genes were identified, which is slightly lower than the predicted proteome size ofP. falciparumandP. vivax4,6.

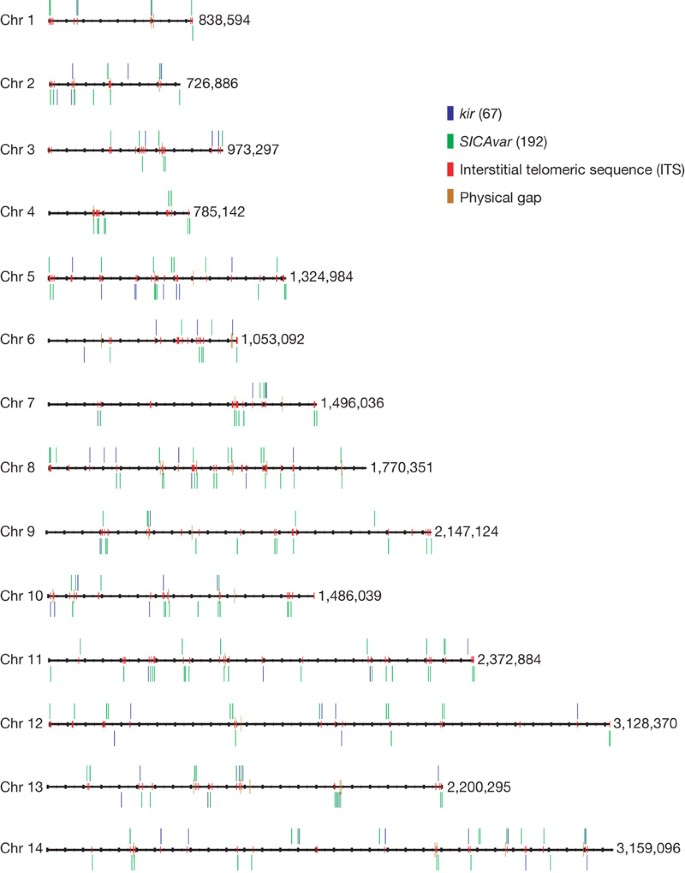

The positions ofkir(shown in blue) andSICAvar(green) genes and gene fragments are shown on all 14 chromosomes. Interstitial telomeric sequences (GGGTT[T/C]A) are found surroundingkirandSICAvargenes (shown in red). The values along the right of each chromosome indicate the total sequence length in base pairs.

Unusually forPlasmodiumspecies, (G+C)-rich repeat regions containing intrachromosomal telomeric sequences (ITSs, containing the heptad sequence GGGTT[T/C]A) are found at multiple internal sites in theP. knowlesichromosomes, arrayed tandemly or as components of larger repeat units (Fig. 1). These sequences appear infrequently inP.vivaxandP. falciparumat internal chromosome sites (Supplementary Figs 6 and 7). In the protozoan parasiteTrypanosoma brucei10,ITSs may be the templates for recombination events that result in gene conversion among variant antigenVSGgenes11.In mammalian genomes12,ITSs are common and may represent the ‘scars’ of double-stranded DNA break repair12.Alternatively, ITSs may have a role in transcriptional control.

For approximately 80% (4,156 out of 5,185) of predicted genes inP. knowlesi,orthologues could be identified in bothP. falciparumandP. vivax(for details, see ref.4). TheP.knowlesi-specific variant antigen gene families,SICAvargenes13andkirgenes9,form the largest groups ofP. knowlesi-specific expansions (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). Five distinct gene families of unknown function, with 4–15 paralogous members, are unique toP. knowlesi(referred to as Pk-fam-a to Pk-fam-e inSupplementary Table 7). Pk-fam-a and Pk-fam-b each have more than nine paralogous members (Supplementary Fig. 8), which have a two-exon gene structure with a signal peptide, a carboxy-terminal transmembrane region, but lack typical export motifs14,15.Members of the protein family Pk-fam-c and Pk-fam-e represent two new families with putative protein export signals (Supplementary Fig. 8andSupplementary Table 8).

A comparison of Pfam domains16between the predicted proteomes ofP. knowlesi,P. vivaxandP. falciparum(Supplementary Table 9,Supplementary Information) revealed major differences in domains that distinguish species-specific protein families involved in antigenic variation. The remainder of the proteome was relatively conserved albeit with some interesting copy number variations of a few key housekeeping enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 9andSupplementary Table 9).

In otherPlasmodiumgenomes sequenced so far, variant gene families involved in antigenic variation (Supplementary Figs 6 and 7) are typically arranged in the subtelomeres, and only a few members of these families have hitherto been found at intrachromosomal sites. Notably, theP.knowlesigenome sequence has revealed that the major variant gene families (that is,SICAvar13andkir9) are randomly distributed across all 14 chromosomes (Fig. 1) and often co-localize with ITS-containing repeats (Supplementary Information). Although all of the telomeres were not fully assembled, we know that in the case of chromosome 7,P. knowlesiandP. vivaxhave atypical gene content—the subtelomere encodes proteins associated with merozoite invasion (for example, MAEBL and members of the reticulocyte-binding-like (RBL) family) (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Variant SICA (schizont-infected cell agglutination) antigens on the surface of infected red blood cells5are associated with parasite virulence17and are encoded by theSICAvargene family13—the largest variant antigen gene family inP. knowlesi.Switching of variant types underlies the establishment of a chronic infection in the vertebrate host, a process that is essential in all species, to ensure mosquito transmission and the completion of the life cycle. Full-lengthSICAvargenes have 3–14 exons (Supplementary Table 5andSupplementary Fig. 11), resulting in a range of sizes for the predicted proteins of 53–247 kDa. Although many of theSICAvargenes are present only as fragments, we estimate that there are up to 107 members in the H strain ofP. knowlesibased on the number of conserved final exons.

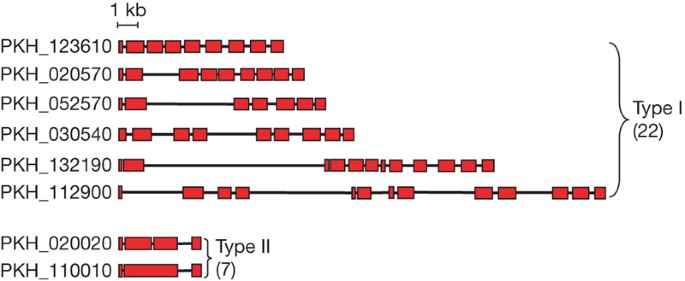

Twenty-nine predictedSICAvargenes have complete gene structures and were divided into two subtypes (Fig. 2). The type ISICAvargenes with 7–14 exons predominate, with a few containing unusually long introns (Fig. 2). The type II subgroup represents smallSICAvargenes with 3–4 exon structures. Unusually large introns (5.8–13.6 kb) are a unique feature ofSICAvargenes and have not previously been seen in any other sequenced apicomplexan gene (Fig. 2).

Schematic view of the exon structure of type I and type IISICAvargenes. Exons are shown as red boxes with introns as joining lines.

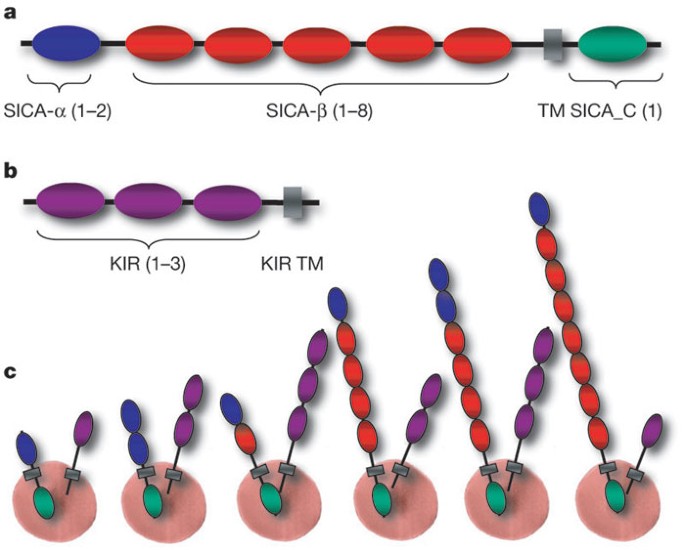

SICA antigens have a modular structure (Fig. 3,Supplementary Fig. 12) comprising a variable number of highly diverged cysteine-rich domains (CRDs) encoded by multiple exons, a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic domain. A high level of sequence diversity was observed, with the exception of the 3′ terminal exon13.We investigated the domain organization of the CRDs using profile hidden Markov models (HMMs;Fig. 3andSupplementary Fig. 13). The full-length SICA proteins contain a distinct five-cysteine CRD (termed SICA-α) at the amino terminus, which occurs once or twice and may have a stabilizing role analogous to the cysteine-rich N-terminal capping motifs of extracellular leucine-rich repeat proteins18.There are 1–8 CRDs (referred to as SICA-β) with 7–10 conserved cysteine residues. The transmembrane domain and a conserved domain follow at the C terminus (termed SICA_C inSupplementary Figs 12 and 13).

a,Domain organization of full-length SICA proteins. The number of different domains (SICA-α, SICA-β and SICA_C) is shown in parentheses. TM, transmembrane.b,Domain organization of full-length KIR proteins.c,Examples of an infected erythrocyte showing SICA and KIR proteins anchored to the surface in different combinations.

AlthoughP. knowlesiandP. falciparumare phylogenetically distant, the SICA andP. falciparumerythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) variant antigens share many fundamental biological characteristics (reviewed in ref.19). Common regulatory mechanisms involving post-transcriptional gene silencing have been proposed between thevargene family inP. falciparumand theSICAvarfamily inP. knowlesi19.We have identified conserved sequence motifs between the singlevarintron andSICAvarintrons (Supplementary Figs 14–18) in the region thought to be the origin of a ncRNA transcript involved in the silencing ofvargenes20,indicating possible commonality in regulatory mechanisms.

We searched for evidence of gene conversion within theSICAvarfamily, using the predicted sequences of 20 type I full-lengthSICAvargenes (Supplementary Information). It is clear that exon shuffling has an important role inSICAvarevolution13.The low-complexity repeat regions found within introns might facilitate recombination through misalignment during mitosis; this could explain the presence ofSICAvarfragments found throughout the genome and/orSICAvargene models with partial intron/exon structures. These comprise whole, and apparently intact, exons that might provide a reservoir for diversification analogous to that seen withVSGgenes inTrypanosoma brucei11(Supplementary Information).

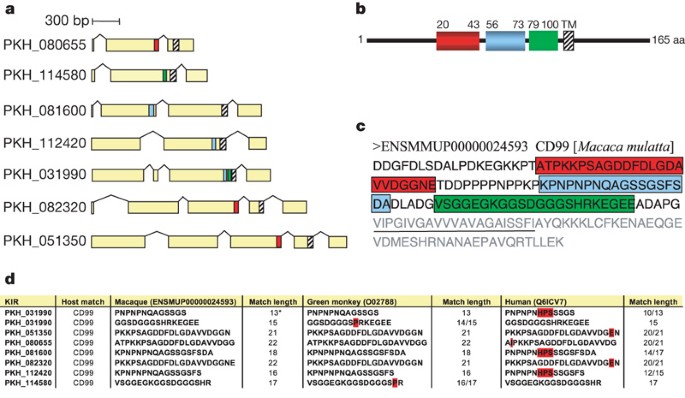

Kirs represent the second largest variant gene family. They encode predicted proteins of 36–97 kDa that are hypothesized to be expressed at the surface of infected erythrocytes and undergo antigenic variation9.There are 68 predictedkirgenes, 4 of which have incomplete structures (Supplementary Table 6). They were divided into four types depending on the number of exons (Supplementary Fig. 19). Most (58 out of 64)kirgenes belong to types I and II. The domain organization of all predicted KIR proteins was also determined using profile HMMs (Fig. 3andSupplementary Fig. 20). They contain 1–3 domains, followed by a transmembrane domain at the C terminus (referred to as KIR TM inSupplementary Fig. 20). A BLAST analysis of KIR proteins revealed stretches of up to 36 amino acids within the predicted extracellular domain that have 100% identity to host proteins, the most striking of which is to CD99. These matches were evident in several KIR proteins. Interestingly, different family members contain matches to different regions of CD99, such that together, they represent over one-half of the CD99 extracellular domain (Fig. 4). Tests were performed to assess the possibility that such matches could occur by chance (Supplementary Table 10). We have compared the sequences toMacaca mulatta,African green monkey and human. The matches exclude conserved cysteine regions and the degree of sequence identity decreases noticeably as the evolutionary distance to the natural host increases (Fig. 4andSupplementary Table 10). CD99 has a critical role as a immunoregulatory molecule in T-cell function (seehttp:// ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/). These exact matches may interfere with recognition of parasitized erythrocytes by the host immune system or act as CD99 analogues that interfere by competing with T cells for CD99 partner molecules.

a,Seven KIRs show conserved matches to three different regions of CD99 (shown in red, blue and green).b,Schematic view ofMacaca mulattaCD99, showing matches to different KIRs. The numbers represent the amino acid position. TM, transmembrane domain. The highlighted regions represent the summary of perfectly matched amino acid stretches in the CD99 extracellular domain to a subgroup of seven KIR proteins.c,Amino acid sequence ofMacaca mulattaCD99, highlighting the summary of matches to KIRs. Amino acids corresponding to the transmembrane domain are underlined. The light-grey amino acids represent the transmembrane domain and the intracellular part of CD99.d,Comparison of the matches toMacaca fascicularis,African green monkey and human. Mismatches are highlighted in red. The asterisk refers to an additional host CD99 match in a KIR protein (PKH_031990) that did not satisfy the minimum length cutoff of 15 amino acids.

We undertook a more systematic search for other such instances of parasite proteins containing extensive stretches of identical host sequences, using the PMATCH algorithm (Supplementary Information). Unsurprisingly, a large number of matches to highly conserved housekeeping genes were observed, but in addition regions of perfect identity to another host protein (known as AHNAK, seehttp:// ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/) were detected in two KIRs and one SICA-like protein (Supplementary Fig. 21andSupplementary Table 10). Analogous searches using the predicted exported protein repertoires (exportome) ofP.vivaxandP.falciparumfound no such matches to host proteins (Supplementary Table 11). The identity to host proteins is maintained at the amino acid sequence rather than DNA sequence level (data not shown).

Acquisition of host proteins, and thus the ability to mimic their function, has been observed in many bacterial and viral pathogens21.In parasitic protozoa there are known cases where stretches of amino acids present on a parasite-encoded cell surface protein match perfectly to regions of host proteins22.However, in all such cases, the matches correspond to a common amino acid repeat that is shared between them22,23,24.Malaria parasites are known to have a potential immunomodulatory role either by secreting functional homologues of host molecules or by binding to host antigen-presenting cells25,26.This is the first observation of its kind in a malaria protein that shows acquisition of host peptide sequences that are likely to be on the infected cell surface and thus may interact with the host. The mechanism by which these host sequences have arisen remains to be clarified. Possible explanations include convergent evolution or horizontal transfer followed by gene degeneration events.

During the intraerythrocytic life cycle, malaria parasites significantly remodel the erythrocyte by exporting numerous proteins14,15.This depends on a short motif, termed the plasmodium export element (PEXEL) or vacuolar transport signal (VTS), which is present in over 300P. falciparumproteins and is common to allPlasmodiumspecies sequenced so far27.In addition to the members of the PHIST family27,an additional 100 proteins inP. knowlesihave typical PEXEL-like motifs (Supplementary Table 8andSupplementary Fig. 22).

Like the PfEMP1 protein inP. falciparum,the SICAs and KIRs lack a signal peptide and a typical PEXEL-motif. We have identified a novel motif in the N-terminal region of SICA-α domains with a positionally conserved tryptophan residue surrounded by hydrophilic residues (Supplementary Fig. 22) that may be the export signal. Similarly, 75% of KIR proteins have a conserved Z-L-P-S motif (where Z denotes a hydrophilic residue) at the beginning of the KIR domain that may also facilitate export (Supplementary Fig. 22). In summary, approximately 280 predictedP. knowlesiproteins may be exported to the infected erythrocyte surface via the PEXEL-dependent or PEXEL-independent pathways. By comparison, the exportome ofP. vivaxis considerably larger than that ofP. knowlesiand seems to be much bigger than previously thought27.About 145P. vivaxproteins contain typical PEXEL motifs including the members of the PHIST family and a small subgroup of 12 VIRs.

Genome sequencing ofP. knowlesiand its comparison with other malaria genomes has highlighted several novel features of this emerging and potentially life-threatening human malaria parasite, and underscores the importance of full genome sequencing of newPlasmodiumspecies. Major differences in both content and organization of its genome were revealed that involve the host–parasite interface, reinforcing the notion that malaria species have evolved specific mechanisms for enhancing their survival within their respective hosts. TheP. knowlesigenome will also greatly enhance the utility of this human-infective species as a model for addressing questions pertinent to allPlasmodiumspecies.

Methods Summary

The random shotgun approach was used to obtain roughly eightfold coverage of the whole nuclear genome sequence from the erythrocyte stage of the Pk1(A+) clone of the H strain ofP. knowlesi5.Sequence reads were assembled (as described in theSupplementary Information) and positional information from sequenced read pairs were used to resolve the orientation and position of the contigs. The assembledP. knowlesicontigs were iteratively ordered and oriented by alignment toP. vivaxassembled sequences (described in ref.4) and by manual checking. Automated predictions from the gene finding algorithms were manually reviewed by comparison to orthologues in otherPlasmodiumspecies. Artemis and Artemis Comparison Tool (ACT) were used (as described previously28) for annotation and curation and viewing the TBLASTX comparisons of regions with conserved synteny betweenP. knowlesi,P. vivaxandP. falciparum.This also allowed us to curate gene models and identify local interruptions of synteny. Functional annotations were based on standard protocols as described previously6.

Online Methods

Parasite material and isolation of genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was isolated from blood drawn from an infected rhesus monkey at 10% ring stage parasitaemia. Blood was Plasmodipur-filtered five times to remove white blood cells and erythrocytes were lysed in 0.1% saponin. Total parasite DNA was isolated using the PUREGENE DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All experimental animal work in these studies was carried out under protocols approved by the independent Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed according to Dutch and European laws.

Sequencing

We sequenced theP. knowlesigenome from plasmid clones containing small fragments of up to 4 kb inserted into pUC19 vector. Problems associated with high G+C sequence were addressed by optimizing the sequence mixture. The quality of reads for the project was as follows: 97.6% ofP. knowlesireads had a quality score of (derived from the PHRED score generated by GAP429) >70 (P= 1 × 10-7). Regions containing repeat sequences or an unexpected read depth were manually inspected. In addition, aP. knowlesifosmid library was constructed in pCC1FOS vector and end sequences were produced (10.5-fold clone coverage) to obtain paired-end information from 40-kb inserts. In particular, we re-examined regions with apparent breaks in synteny for potential misassembly errors and location of several intrachromosomal telomeric-repeat (GGGTT[T/C]A) sequences associated withSICAvarandkirgenes. Sequence reads were assembled with PHRED/PHRAP on the basis of overlapping sequence and were manually edited in GAP4 database29.Information from oriented read pairs, together with additional sequencing from selected large-insert clones and synteny withP. vivaxchromosomes, were used to resolve potential misassemblies. Using long-range sequence information from the fosmid end sequences, we were able to bridge 142 out of 190 total gaps (Supplementary Table 1).

Gene finding and genome annotation

Annotation (PK4 version of assembly) was performed using the Artemis30and ACT software31.Genes were identified by manual curation of the output of the gene finding software SNAP32and Annotaid (an extension of the comparative gene prediction program Projector33;I. M. Meyer, unpublished). A set of 100 manually curatedPlasmodium knowlesigenes was used as the training set for SNAP predictions. Annotaid was optimized for genome-wide analysis by training its parameters with a manually curated training set of 180 orthologous gene pairs fromP. knowlesiandP. falciparum.

Functional assignments were based on assessment of BLAST and FASTA similarity searches against public databases and searches in protein domain databases such as InterPro34.In addition, TMHMMv2.035,SignalPv3.036and t-RNA scan37were used to identify transmembrane domains, signal peptides and t-RNA genes.

To define the orthologous and paralogous relationships between the predicted proteomes of threePlasmodiumspecies (P. falciparum,P. knowlesi,P. vivax), the OrthoMCL protein clustering algorithm38was used with an inflation value of 1.5.

To search for parasite proteins containing stretches of perfectly matched host sequences, the PMATCH algorithm (R. Durbin, unpublished) was used to report exact matches of 15 amino acids or greater after screening out low complexity sequences (details are provided inSupplementary Information).

Building profile HMMs of SICA and KIR protein domains

Sequence alignments and dotter39analysis of SICA proteins revealed the presence of a distinct N-terminal cysteine-rich domain (termed SICA-α: in some cases there are two copies of this domain), multiple central cysteine-rich domains (SICA-β) and a C-terminal cytoplasmic encoding domain (SICA_C). For each domain, a profile HMM (using HMMer,http://hmmer.janelia.org/) was constructed and searched against theP. knowlesigenome to find all examples of the domain (significant matches hadE-values <0.001). The HMMs were rebuilt, using alignments constructed using all significant hits, and re-searched until no additional examples of the domain were found.

The program Phobius40was used to identify the putative transmembrane region located between the end of the last SICA-β domain and the SICA_C domain in all cases. An identical procedure was used to identify the domains in the KIR proteins. In this case, a single domain type was found on all KIR proteins, repeated between one and three times. Putative transmembrane proteins were identified as before, but only∼50% of KIR proteins had a predicted transmembrane region. Visual inspection of the corresponding C-terminal regions from sequences, both with and without predictions, showed the presence of a common hydrophobic patch. To investigate whether the Phobius40software was insufficiently sensitive to identify all of the KIR transmembrane regions, the predicted transmembrane regions were aligned and used to build a HMM of the transmembrane region. This was then used to iteratively search the whole genome as before.

Accession codes

Primary accessions

EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ

Data deposits

The annotation and sequence data for the 14 chromosomes of the H strain ofP. knowlesihave been submitted to the EMBL database with the following accession numbers:AM910983–AM910996.The annotation and sequence data are also available athttp:// genedb.organdhttp:// plasmodb.org.

References

Cox-Singh, J. et al.Plasmodium knowlesimalaria in humans is widely distributed and potentially life-threatening.Clin. Infect. Dis.46,165–171 (2008)

White, N. J.Plasmodium knowlesi:the fifth human malaria parasite.Clin. Infect. Dis.46,172–173 (2008)

Brown, K. N. & Brown, I. N. Immunity to malaria: antigenic variation in chronic infections ofPlasmodium knowlesi.Nature208,1286–1288 (1965)

Carlton, J. M. et al. Comparative genomics of the neglected human parasitePlasmodium vivax.Nature10.1038/nature07327 (this issue)

Howard, R. J., Barnwell, J. W. & Kao, V. Antigenic variation ofPlasmodium knowlesimalaria: identification of the variant antigen on infected erythrocytes.Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA80,4129–4133 (1983)

Gardner, M. J. et al. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasitePlasmodium falciparum.Nature419,498–511 (2002)

Carlton, J. M. et al. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the model rodent malaria parasitePlasmodium yoelii yoelii.Nature419,512–519 (2002)

Hall, N. et al. A comprehensive survey of thePlasmodiumlife cycle by genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses.Science307,82–86 (2005)

Janssen, C. S., Phillips, R. S., Turner, C. M. & Barrett, M. P.Plasmodiuminterspersed repeats: the major multigene superfamily of malaria parasites.Nucleic Acids Res.32,5712–5720 (2004)

Berriman, M. et al. The genome of the African trypanosomeTrypanosoma brucei.Science309,416–422 (2005)

Barry, J. D. et al. What the genome sequence is revealing about trypanosome antigenic variation.Biochem. Soc. Trans.33,986–989 (2005)

Nergadze, S. G., Rocchi, M., Azzalin, C. M., Mondello, C. & Giulotto, E. Insertion of telomeric repeats at intrachromosomal break sites during primate evolution.Genome Res.14,1704–1710 (2004)

al-Khedery, B., Barnwell, J. W. & Galinski, M. R. Antigenic variation in malaria: a 3′ genomic alteration associated with the expression of aP.knowlesivariant antigen.Mol. Cell3,131–141 (1999)

Hiller, N. L. et al. A host-targeting signal in virulence proteins reveals a secretome in malarial infection.Science306,1934–1937 (2004)

Marti, M., Good, R. T., Rug, M., Knuepfer, E. & Cowman, A. F. Targeting malaria virulence and remodeling proteins to the host erythrocyte.Science306,1930–1933 (2004)

Finn, R. D. et al. The Pfam protein families database.Nucleic Acids Res.36(Database issue) D281–D288 (2008)

Barnwell, J. W., Howard, R. J., Coon, H. G. & Miller, L. H. Splenic requirement for antigenic variation and expression of the variant antigen on the erythrocyte membrane in clonedPlasmodium knowlesimalaria.Infect. Immun.40,985–994 (1983)

Kajava, A. V. Structural diversity of leucine-rich repeat proteins.J. Mol. Biol.277,519–527 (1998)

Galinski, M. R. & Corredor, V. Variant antigen expression in malaria infections: posttranscriptional gene silencing, virulence and severe pathology.Mol. Biochem. Parasitol.134,17–25 (2004)

Deitsch, K. W., Calderwood, M. S. & Wellems, T. E. Malaria: Cooperative silencing elements invargenes.Nature412,875–876 (2001)

Finlay, B. B. & McFadden, G. Anti-immunology: evasion of the host immune system by bacterial and viral pathogens.Cell124,767–782 (2006)

Werner, E. B., Taylor, W. R. & Holder, A. A. APlasmodium chabaudiprotein contains a repetitive region with a predicted spectrin-like structure.Mol. Biochem. Parasitol.94,185–196 (1998)

Goundis, D. & Reid, K. B. Properdin, the terminal complement components, thrombospondin and the circumsporozoite protein of malaria parasites contain similar sequence motifs.Nature335,82–85 (1988)

Hall, R. et al. Mimicry of elastin repetitive motifs byTheileria annulatasporozoite surface antigen.Mol. Biochem. Parasitol.53,105–112 (1992)

MacDonald, S. M. et al. Immune mimicry in malaria:Plasmodium falciparumsecretes a functional histamine-releasing factor homologin vitroandin vivo.Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA98,10829–10832 (2001)

Urban, B. C. et al.Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes modulate the maturation of dendritic cells.Nature400,73–77 (1999)

Sargeant, T. J. et al. Lineage-specific expansion of proteins exported to erythrocytes in malaria parasites.Genome Biol.7,R12 (2006)

Berriman, M. & Harris, M. Annotation of parasite genomes.Methods Mol. Biol.270,17–44 (2004)

Bonfield, J. K., Smith, K. & Staden, R. A new DNA sequence assembly program.Nucleic Acids Res.23,4992–4999 (1995)

Rutherford, K. et al. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation.Bioinformatics16,944–945 (2000)

Carver, T. J. et al. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool.Bioinformatics21,3422–3423 (2005)

Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes.BMC Bioinformatics5,59 (2004)

Meyer, I. M. & Durbin, R. Gene structure conservation aids similarity based gene prediction.Nucleic Acids Res.32,776–783 (2004)

Mulder, N. J. et al. InterPro, progress and status in 2005.Nucleic Acids Res.33(Database Issue) D201–D205 (2005)

Krogh, A., Larsson, B., von Heijne, G. & Sonnhammer, E. L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes.J. Mol. Biol.305,567–580 (2001)

Bendtsen, J. D., Nielsen, H., von Heijne, G. & Brunak, S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0.J. Mol. Biol.340,783–795 (2004)

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence.Nucleic Acids Res.25,955–964 (1997)

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J. & Roos, D. S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes.Genome Res.13,2178–2189 (2003)

Sonnhammer, E. L. & Durbin, R. A dot-matrix program with dynamic threshold control suited for genomic DNA and protein sequence analysis.Gene167,GC1–GC10 (1995)

Kall, L., Krogh, A. & Sonnhammer, E. L. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method.J. Mol. Biol.338,1027–1036 (2004)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute core sequencing and informatics groups. The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust through its support to the Pathogen Sequencing Unit at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. We thank J. Barnwell for providing the Pk1(A+) clone of the H strain of the parasite for the generation of genomic DNA by A. Thomas. We thank A. Voorberg-vd Wel (BPRC, Rijswijk) for technical assistance. We thank D. Fergusson for providing us with the electron micrograph image of the erythrocyte, used inFig. 2.Part of this work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, NIH, BioMalPar and the Virimal contract. This work is dedicated to the memory of Marie-Adele Rajandream.

Author ContributionsB.G.B., C.I.N., N.H., A.W.T. and C.M.R.T. initiated the project. M.A.Q., T.C., H.H., S.M., D.O., S.S., N.L., F.S., K.Br., R.S., S.T., S.M., M.Sa., M.Si., B.W. and D.W. constructed DNA libraries and performed sequencing; B.W., M.S. and I.C. finished and assembled sequence data; K.M., D. Harris and C.Ch. managed finishing and sequencing teams; M.A.R. managed the computational and bioinformatics support team; M.A.A., S.B., T.J.C., D. Harper, T.K., A.R.T., E.Z. and N.P. provided computational and bioinformatic support; U.B., A.E.B., E.M.P., S.L. and B.G.B. annotated the genome data. U.B., A.E.B., I.M.M., C.Ca., C.I.N., R.D.F., J.M., T.M., C.M.R.T., T.G.C., K.Bo., M.R.G., C.S.J., T.J.S., M.M., A.F.C., A.P.J., C.H.M.K., M.B. and A.P. contributed specific analysis topics presented in this manuscript or contributed data to characterize the genome and commented on manuscript drafts. U.B. performed data submission in EMBL. A.P., M.B., A.E.B., U.B. and C.I.N. drafted and edited the paper. A.P. and M.B. directed the project and A.P. assembled the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Notes, Supplementary Figures 1-28 with Legends and Supplementary Tables 1-3 and 11-14 (PDF 7475 kb)

Supplementary Table 4

This file contains Supplementary Table 4 with Legend (XLS 47 kb)

Supplementary Table 5

This file contains Supplementary Table 5 with Legend (XLS 93 kb)

Supplementary Table 6

This file contains Supplementary Table 6 with Legend (XLS 54 kb)

Supplementary Table 7

This file contains Supplementary Table 7 with Legend (XLS 50 kb)

Supplementary Table 8

This file contains Supplementary Table 8 with Legend (XLS 39 kb)

Supplementary Table 9

This file contains Supplementary Table 9 with Legend (PDF 1379 kb)

Supplementary Table 10

This file contains Supplementary Table 10 with Legend (PDF 112 kb)

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), which permits distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This licence does not permit commercial exploitation, and derivative works must be licensed under the same or similar licence.

About this article

Cite this article

Pain, A., Böhme, U., Berry, A.et al.The genome of the simian and human malaria parasitePlasmodium knowlesi. Nature455,799–803 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07306

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07306

This article is cited by

-

Malaria & mRNA Vaccines: A Possible Salvation from One of the Most Relevant Infectious Diseases of the Global South

Acta Parasitologica(2023)

-

Systems biology of malaria explored with nonhuman primates

Malaria Journal(2022)

-

Plasmodium knowlesi: the game changer for malaria eradication

Malaria Journal(2022)

-

The first complete genome of the simian malaria parasite Plasmodium brasilianum

Scientific Reports(2022)

-

Malaria-Antigene in der Ära der mRNA-Impfstoffe

Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde(2022)