- 1Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Yunnan, China

- 2Germplasm Bank of Wild Species, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Yunnan, China

- 3Kunming College of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- 4Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

The subfamily Cercidoideae is an early-branching legume lineage, which consists of 13 genera distributed in the tropical and warm temperate Northern Hemisphere. A previous study detected two plastid genomic variations in this subfamily, but the limited taxon sampling left the overall plastid genome (plastome) diversification across the subfamily unaddressed, and phylogenetic relationships within this clade remained unresolved. Here, we assembled eight plastomes from seven Cercidoideae genera and conducted phylogenomic-comparative analyses in a broad evolutionary framework across legumes. The plastomes of Cercidoideae all exhibited a typical quadripartite structure with a conserved gene content typical of most angiosperm plastomes. Plastome size ranged from 151,705 to 165,416 bp, mainly due to the expansion and contraction of inverted repeat (IR) regions. The order of genes varied due to the occurrence of several inversions. InTylosemaspecies, a plastome with a 29-bp IR-mediated inversion was found to coexist with a canonical-type plastome, and the abundance of the two arrangements of isomeric molecules differed between individuals. Complete plastome data were much more efficient at resolving intergeneric relationships of Cercidoideae than the previously used selection of only a few plastid or nuclear loci. In sum, our study revealed novel insights into the structural diversification of plastomes in an early-branching legume lineage, and, thus, into the evolutionary trajectories of legume plastomes in general.

Introduction

Chloroplast genomes (plastomes) of photosynthetic angiosperms usually are highly conserved regarding their overall gene content (115–160 genes) and order and GC content (34–40%). They often present a quadripartite structure that consists of a pair of large inverted repeats (IRs; usually around 25 kb, but can vary from 7 to 88 kb) separated by large and small single copy regions (LSC of ca. 80 kb length and SSC of ca. 20 kb, respectively) (Jansen and Ruhlman, 2012;Ruhlman and Jansen, 2014). The large IRs of the plastome are hypothesized to contribute to plastome stabilization, because their absence often coincides with additional severe changes of gene order (Palmer and Thompson, 1982), although causation remains unclear. With the advent of next-generation sequencing, complete plastome sequencing has increased dramatically. We are becoming more and more aware of an increasing number of plastome rearrangements also in photosynthetic angiosperms that retain a quadripartite structure, like in Campanulaceae (Cosner et al., 2004;Haberle et al., 2008), Geraniaceae (Palmer et al., 1987;Chumley et al., 2006;Guisinger et al., 2011;Weng et al., 2014), or Oleaceae (Lee et al., 2007).

The legume family (Fabaceae) is notable for its departures from the typical plastome structure, of which several rearrangements are of phylogenetic relevance. Plastome size in legumes varies greatly because of either expansion, contraction or loss of the IR. Smaller plastomes characterize species of the inverted repeat-lacking clade (IRLC), which have lost the IR (Wojciechowski et al., 2000). In contrast, larger plastomes are typical of species in the inverted repeat-expanding clade (IREC) that have IRs expanding into the SSC by ca. 13 kb (Dugas et al., 2015;Wang et al., 2017a). The loss of two housekeeping genes, namely the translation initiation factor (infA) and the ribosomal protein L22 (rpl22), is shared among all legumes (Gantt et al., 1991;Magee et al., 2010). Other genes, such asaccD, clpP, psaI, rpl33, rps16,andycf4,have been functionally lost in various legume lineages (Keller et al., 2017). In addition, group IIA-introns have been lost fromclpP, rpl2,andrps12in various legume lineages (Doyle et al., 1995;Jansen et al., 2008;Dugas et al., 2015;Wang et al., 2017a). Many of these unusual plastome features of legumes known so far are restricted to papilionoids and mimosoids, and modifications of the “normal” angiosperm plastome structure (a unique 7.5-kb inversion and 5-kb IR expansion into SSC) have been reported only inTylosema esculentumof Cercidoideae (Kim and Cullis, 2017).

Plastome inversions are common in papilionoids. Except for a few of early diverging lineages of papilionoids, members of this subfamily typically share a 50-kb inversion in the LSC (Doyle et al., 1996). A 78-kb inversion characterizes the subtribe Phaseolinae of Phaseoleae (Bruneau et al., 1990), whereas inRobiniaa 39-kb inversion is known (Schwarz et al., 2015). Inversions of 23, 24, or 36 kb have been reported in different taxa of the Genistoid clade (Martin et al., 2014;Choi and Choi, 2017;Feng et al., 2017;Keller et al., 2017), and multiple inversions have been detected in IRLC-legumes (Milligan et al., 1989;Cai et al., 2008;Sabir et al., 2014;Sveinsson and Cronk, 2014;Lei et al., 2016). However, only two inversions have been reported in other legumes, including the aforementioned 7.5-kb inversion fromT. esculentum(Kim and Cullis, 2017) and a 421-bp inversion from a mimosoid species (Wang et al., 2017a). The 36-kb and 39-kb inversions of some genistoids andRobiniamentioned above, respectively, are both located between a pair of 29-bp short inverted repeats situated in the 3′-ends of twotrnSgenes. Inverted repeats are thought to contribute to inversions by mediating intramolecular recombination that may result in the formation of isomers. The most typical example of such isomers is illustrated by the relative orientation of single copy (SC) regions existing in a single plant as demonstrated byPalmer (1983).Besides,Stein et al. (1986)predicted a universal existence of isomeric plastomes in all plastomes with typical IRs. Some isomeric plastomes caused by small inverted repeats other than the primary IRs have been reported in several conifers (Tsumura et al., 2000;Wu et al., 2011;Yi et al., 2013;Guo et al., 2014;Qu et al., 2017b). However, it remains unknown whether the 29-bp IRs in legume plastomes could also mediate isomers.

Cercidoideae is one of six recently recognized subfamilies of Fabaceae (LPWG, 2017) and probably represents the first-branching legume lineage (Bruneau et al., 2001;Herendeen et al., 2003). This subfamily consists of ca. 335 species in 13 genera that are distributed in tropical and warm temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere (Clark et al., 2017;LPWG, 2017). Some of its species are of economic value to humans. For instance, several species ofBarklya, Bauhinia, Cercis, Griffonia, Phanera, Piliostigma,andTylosemaare valued for the production of foods, timbers, dyes, or ropes, or they find application as medicinal and ornamental plants, or even as coffee substitutes (Lewis et al., 2005). Phylogenetically, intergeneric relationships of Cercidoideae remain unresolved in previous phylogenetic studies (Bruneau et al., 2008;Sinou et al., 2009;LPWG, 2013,2017). Clarifying relationships in Cercidoideae will facilitate many aspects of studies on this economically important group, and contribute to elucidating the evolutionary trajectory of plastid genome evolution in legumes in general. Given plastome variations having been found in only four published species, it is likely that more divergent plastomes hide in Cercidoideae.

Here, we present an analysis of eight newly sequenced plastomes of Cercidoideae. We complement our dataset with four more species from three genera of this subfamily and 45 other legumes to reconstruct the phylogeny of Cercidoideae based on 77 protein-coding genes, 136 intergenic spacers, and 19 introns. Our comparative plastome analysis involving examinations of IR boundary shifts, inversions and locally collinear blocks (LCB), and the existence of isomeric plastomes uncovers unique plastome features and illustrates the variation of plastomes in this clade. Finally, a critical review of plastome structures across the legume family sheds further light on the mechanisms of plastome evolution in Fabaceae.

Materials and Methods

Plant Sampling

For the plastome analysis, we sampled fresh or silica gel-dried leaves of eight species representing seven genera of the subfamily Cercidoideae. Of these, plastomes of generaBarklya, Bauhinia, Griffonia, Lysiphyllum, Piliostigma,andSchnellawere sequenced for the first time. To verify the existence of isomeric plastomes, we isolated total genomic DNA of three additional individuals of twoTylosemaspecies. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes voucher information and material type for sampled plants.

Chloroplast DNA Extraction and Sequencing

Total genomic DNA was isolated with a modified CTAB (Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide) method described inYang et al. (2014).For species from which DNA was obtained from fresh leaves, chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) was amplified using long-range PCR (LPCR) with fifteen primer pairs described inZhang et al. (2016).DNA extracts and cpDNA-amplicons were fragmented for short-insert, paired-end (PE) library construction and sequenced on either an Illumina HiSeq 2000/2500 or X-Ten instrument at Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI, Shenzhen, China), or at the Plant Germplasm and Genomics Center, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences (KIB, CAS, Kunming, China), respectively.

Plastome Assembly and Annotation

All raw sequence data from LPCR-based plastome enrichment was quality-checked using the NGS QC Tool Kit (Patel and Jain, 2012) with default parameters. High-quality PE reads werede novoassembled into contigs usingCLC Genomics Workbenchv.8.5.1 with a k-mer of 63 and an automatic bubble size. We retained only contigs with a minimum length of 1 kb and aligned these withHaematoxylum brasiletto(NC_026679) as reference employing nucleotide BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) at default search parameters. Then, the most probable order of the aligned contigs was determined according to the reference plastome, and the gaps between the contigs were filled by mapping the raw reads to the reference plastome. For shotgun-sequenced genomic DNA, raw reads were filtered and assembled into contigs using GetOrganelle.py1with the plastome ofH. brasilettoas the reference. Contigs were then connected with the help of Bandage Ubuntu dynamic v.080 (Wick et al., 2015) and manual correction where necessary.

Annotation of the plastomes was performed in DOGMA (Wyman et al., 2004), coupled with manual corrections in Geneious v.9.0.2 (Biomatters, Inc.). Protein coding genes were double-checked by finding open reading frames using the Find ORFs function in Geneious v.9.0.2. We used the online tRNAscan-SE service (Schattner et al., 2005) to improve the identification of tRNA genes. Physical maps of all sequenced plastomes were prepared with OrganellarGenomeDRAW v.1.2 (Lohse et al., 2013), and are enclosed here as Supplementary Figure S1. To detect the number of matched reads and the depth of coverage, raw reads were remapped to the assembled plastomes with Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012), implemented in Geneious v.9.0.2. We used the End-to-End alignment type and Medium Sensitivity/Fast preset, and adjusted the maximum insert size to 800 bp; sequences remained untrimmed before mapping. The final annotated plastomes are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MF135594-MF135601 (Table1).

Analysis of Plastome Rearrangements and Inversions

To detect the breakpoints of inversions in the plastomes ofGriffonia simplicifolia, Piliostigma thonningii, Tylosema esculentum,andT. fassoglensis,and to identify locally collinear blocks (LCBs) in plastomes of all sampled legumes (see “Phylogeny reconstruction” in Section “Materials and Methods” and Supplementary Table S2), we performed a whole-plastome alignment using Mauve v.2.3.1 (Darling et al., 2010), implemented in Geneious v.9.0.2. To this end, we used the progressiveMauve algorithm with both the seed weight and minimum LCB score being calculated automatically. To detect the breakpoints of inversions in those four species, the plastome ofCercis glabra,which has a typical angiosperm plastome organization, was used as the reference in Mauve alignments. For the Mauve alignment of all sampled legumes, species were ordered Alpha betically. Because IRLC legumes all lost the IRAin their plastomes, the IRAof plastomes was removed for each species outside the IRLC.

Analysis of Isomeric Plastomes

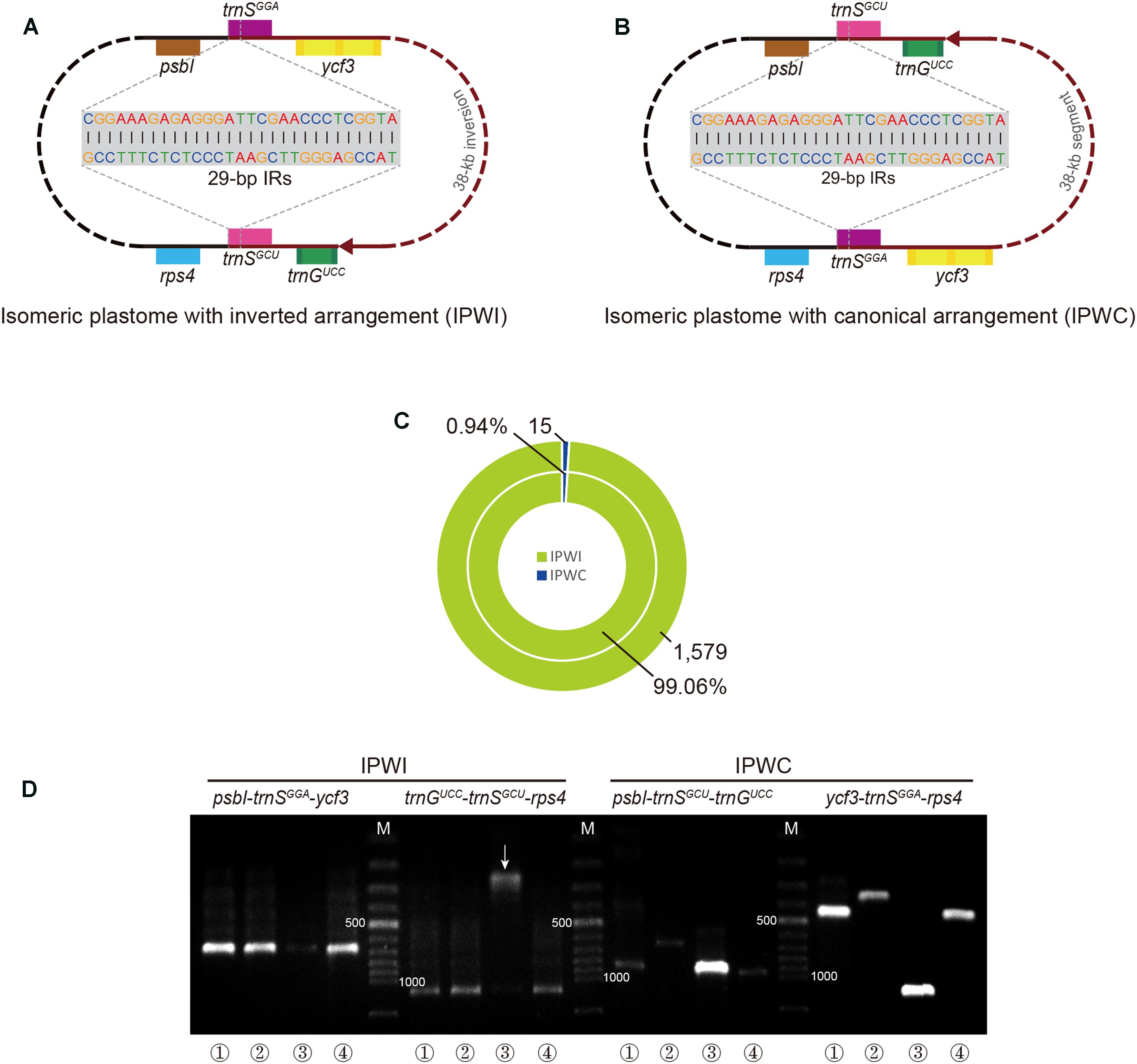

We found a 38-kb inversion between a pair of 29-bp IRs in the 3′-ends oftrnSGCUandtrnSGGAthat was absent from the plastome of the previously publishedTylosemaspecies (Kim and Cullis, 2017). We pursued two approaches to explore whether a plastome with this inversion coexists with a canonical plastome inTylosema fassoglensisand otherTylosemaspecies: Firstly, we used Bowtie2 (as before) to map raw PE reads ofT. fassoglensisto the four regions corresponding to the breakpoints of the inversion. For convenience, we here defined the plastome with the 38-kb inversion as IPWI (isomeric plastome with inverted arrangement), whereas the plastome with its reverse-complement (canonical) orientation as IPWC (isomeric plastome with canonical arrangement). Accordingly,psbI-trnSGGA-ycf3andtrnGUCC-trnSGCU-rps4both were captured from IPWI, whereaspsbI-trnSGCU-trnGUCCandycf3-trnSGGA-rps4were captured from IPWC. Secondly, we performed a PCR assay with specially designed primer pairs that target all four breakpoint regions of the isomeric plastomes. In so doing, we included three additional individuals ofTylosema(Supplementary Table S1) to investigate the universality of the isomeric plastomes in this genus. Each of the 25.5 μL PCR reaction mixture contained 1 μL total genomic DNA (ca. 100 ng/μL) as the template, 0.5 μL each of the forward and reverse primers (10 μmol/L), 12.5 μL Tiangen 2× Taq PCR MasterMix, and 11 μL double-distilled water. To account for potentially different qualities of the template DNAs as well as the possibility of the non-universality of the primer pairs, we used different primer pairs and PCR conditions in our screening, as detailed in Supplementary Table S3.

Phylogenetic Reconstructions

To reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among Cercidoideae and other legumes, we complemented our data set of eight Cercidoideae species with 49 previously published legume plastomes (Kato et al., 2000;Saski et al., 2005;Guo et al., 2007;Jansen et al., 2008;Magee et al., 2010;Kazakoff et al., 2012;Sabir et al., 2014;Sveinsson and Cronk, 2014;Dugas et al., 2015;Lei et al., 2016;Choi and Choi, 2017;Donkpegan et al., 2017;Feng et al., 2017;Kim and Cullis, 2017;Wang et al., 2017a,bandCadellia pentastylis(Surianaceae; Li et al., unpublished data) as outgroups (Supplementary Table S2). Protein coding (CDS) and non-genic (intergenic [IGS] and intron) sequences were extracted and aligned to generate original CDS, IGS and intron alignments, respectively, using MAFFT v.7.271 (Katoh and Standley, 2013) with default parameters. Ambiguously aligned sites in all these alignments were removed using GBLOCKS v.0.91b (Castresana, 2000;Talavera and Castresana, 2007) with default parameters, except that all gap positions were allowed. All original alignments and the GBLOCKS-edited versions were concatenated separately to generate supermatrices. Four more supermatrices of original and GBLOCKS-edited alignments for non-genic regions (IGS + intron, hereafter: NGS) and all plastome regions (CDS + IGS + intron) were then obtained by concatenating the corresponding supermatrices. These datasets were subjected to maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic reconstructions using RAxML-HPC v.8.2.4 (Stamatakis, 2014) with the GTR-CAT substitution model and 1,000 replicates of rapid bootstrap.

Results

Organization of Cercidoideae Plastomes

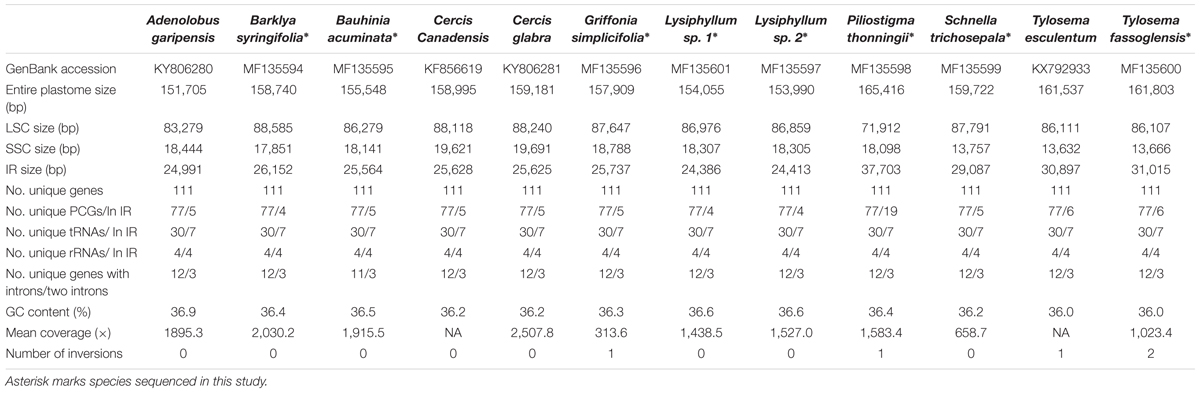

Due to differences regarding both the plant materials and the experimental procedures, the average plastome coverage varied significantly from 313.6× to 2030.2× (Table1). While the total plastome sizes, including their respective LSC, SSC, and IR regions, differ considerably, we observed only marginal variation in GC contents (36.0 to 36.6%). Plastome size among the sampled Cercidoideae species ranges from 151,705 bp inAdenolobus garipensisto 165,416 bp inPiliostigma thonningii.The length of IR ranges from 24,386 bp inLysiphyllumsp. 1 to 37,703 bp inP. thonningii.This followed the substantial length variation for LSC from 71,912 bp inP. thonningiito 88,585 bp inBarklya syringifolia.The length of the SSC also varies substantially, ranging from 13,632 bp inTylosema esculentumto 19,691 bp inCercis glabra.

Plastome Rearrangement

All sampled plastomes of Cercidoideae exhibit a typical quadripartite structure and a conserved gene content; onlyBauhinia acuminatahas lost therpl2intron (Supplementary Figure S1). The plastidaccDgenes in species ofBarklya, Lysiphyllum, Schnella,andTylosemaapparently lack 260-714 bp at their respective 5′-ends, and thematKgenes ofTylosemaare 131-bp shorter at their 5′-ends compared with other Cercidoideae species. However, both genes retain intact open reading frames (ORFs).

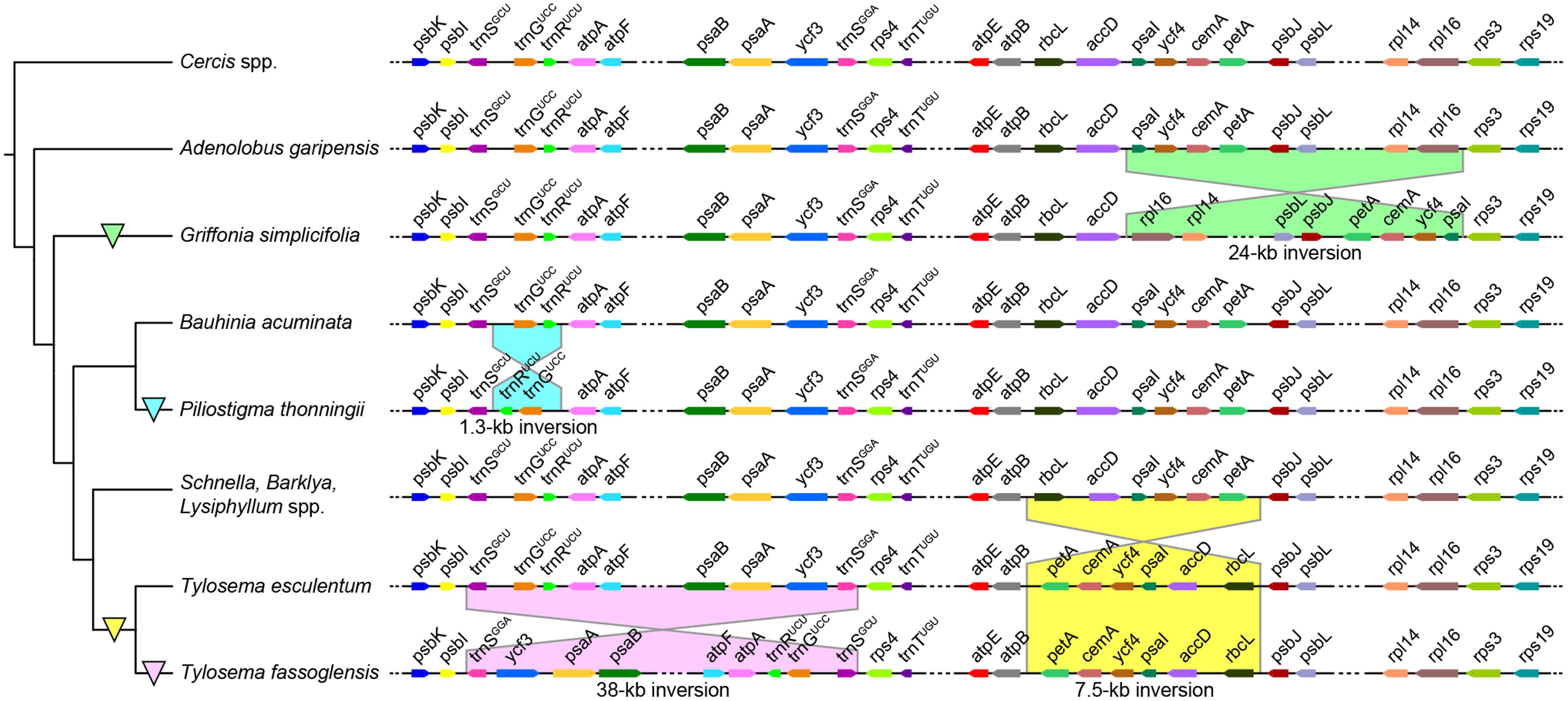

Unlike gene content, gene order differs notably between species due to the occurrence of several inversions (Figure1). The plastome ofGriffonia simplicifoliahas a 24-kb inversion from itsrpl16gene topsaI,resulting in the adjacencies ofaccDwithpsaIandrpl16withrps3.In contrast, a 1.3-kb inversion fromtrnRUCUandtrnGUCC,which results intrnSGCUneighboringtrnRUCUandtrnGUCCbeing adjacent toatpA,characterizes the plastome ofP. thonningii.Tylosema fassoglensishas two inversions in its plastome, one of which is a 7.5-kb inversion spanning fromrbcLtopetA,thus resulting in the colocalizations ofatpBwithpetAandrbcLwithpsbJ– a gene order seen inT. esculentum,too. The second inversion of 38 kb in size lies between the 29-bp IRs at the 3′ -ends oftrnSGCUandtrnSGGAgenes, and, in consequence,psbIis positioned adjacent totrnSGGAandtrnSGCUneighborsrps4.

FIGURE 1.Plastome inversions in Cercidoideae.Griffonia, Piliostigma,andTylosemashow independent inversions in their LSCs compared with other closely related Cercidoideae. The partial plastome maps(right)are not drawn to scale, and the tree topology(left)is depicted according to our phylogenic reconstructions based on the combined plastid coding regions (see Results). Colored triangles on branches demarcate the evolutionary origin of the inversion shown to the right.

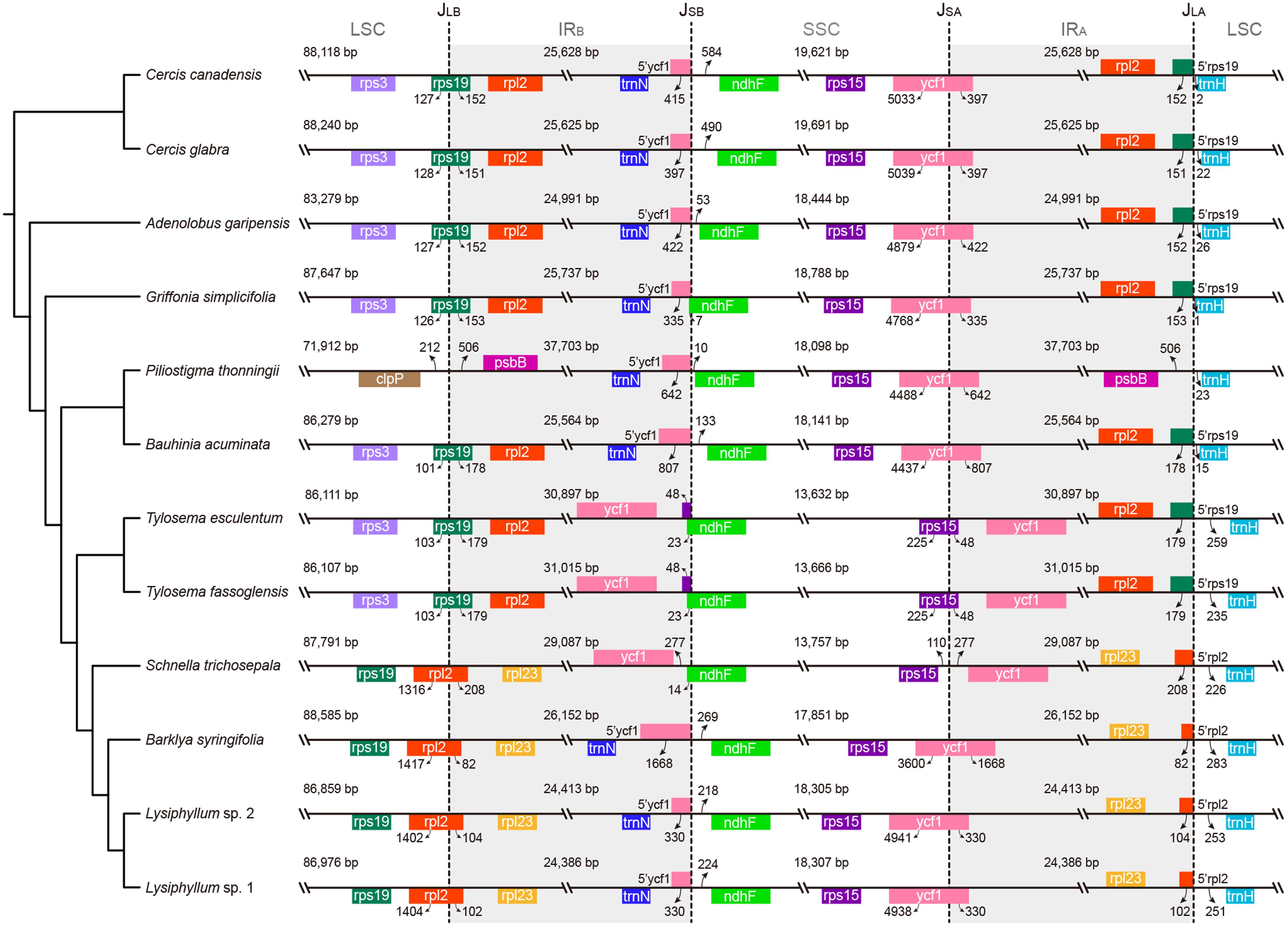

The plastomes ofAdenolobus, Bauhinia, Cercis,andGriffoniahave a conserved IR length, ranging from 24,991 (A. garipensis) to 25,737 bp (G. simplicifolia) (Figure2and Supplementary Figure S1). The locations of IR-SC junctions of these plastomes are also similar to other canonical angiosperm plastomes. Specifically, the LSC/IRBjunction (JLB) lies within therps19gene, which leads to some length variation regarding the duplicated 3’-ends of this gene (from 151 bp inCercis glabrato 178 bp inBau. acuminate) at the border of the IRA/LSC junction (JLA) betweenrpl2(IRA) andtrnH(LSC). The position of the IRA/SSC junction (JSA) is within theycf1.Hence, the duplicated 3′-ends ofycf1range from 335 (G. simplicifolia) to 807 bp (Bau. acuminata) at the border of the IRB/SSC junction (JSB) betweentrnN(IRB) andndhF(SSC). The plastomes ofBar. syringifolia, Lysiphyllumsp. 1,Lysiphyllumsp. 2, andSchnella trichosepalauniformly exhibit a contraction of their IRs. Their LSCs are narrowed by ca. 1.6 kb due to a shift of the JLBinto the 3′-exon ofrpl2through which 82 (Bar. syringifolia) to 208 bp (S. trichosepala) of this gene’s 3′-ends is duplicated in the IRA.Among these taxa,S. trichosepalaalso displays an expansion of approximately 5 kb on the opposite end of its IR, which now contains the entireycf1gene, and the JSBlies in the 5′-end ofndhF(14 bp are duplicating in IRA).Tylosema esculentumandT. fassoglensissimilarly expanded their IRs to contain intactycf1;JSBand JSAare accordingly shifted intondhFandrps15,respectively. The IRs ofBar. syringifoliaexpand by ca. 1.3 kb into the SSC but the IR/SSC junction remains within theycf1coding region. With a gain of 12 kb in size,P. thonningiishows the most extreme IR expansion, leading to the duplication of bothrps19and 13 other genes spanning fromrps3topsbB,and the JLBlies in the intergenic spacer ofclpPandpsbB.

FIGURE 2.IR/SC junctions in Cercidoideae plastomes. Junctions from IRs into single-copy regions are depicted for all Cercidoideae, which are arranged according to their phylogenetic placement. JLB,JSB,JSA,and JLArefer to the junctions of LSC/IRB,SSC/IRB,SSC/IRA,and LSC/IRA,respectively. Genes are indicated by colored boxes above (encoded on the plus strand) and below (minus strand) the horizontal lines. The tree topology (left) is modified from our reconstructed phylogeny (as in Figure1;see Results).

Isomeric Plastomes inTylosemaSpecies

A schematic of the endpoint location of isomeric plastomes is depicted in Figures3A,B.According to the read-mapping results of the putativeT. fassoglensisisomers, 1,579 reads of the over 15 million PE reads obtained by sequencing span the 29-bp IRs in the IPWI orientation, whereas only 15 sequences cover the 29-bp IRs in the IPWC type. Consequently, the frequency of the IPWI and IPWC can be assumed as 99.06% and 0.94%, respectively (Figure3C). Details regarding the statistics of the read-mapping results are presented in Supplementary Table S4. Using PCR validations, the coexistence of IPWI and IPWC was demonstrated to occur also in other three individuals ofTylosema(Figure3D). In general, gel electrophoresis revealed fragments for IPWI ofT. fassoglensis, T. fassoglensis1, andT. esculentumto be much brighter, i.e., more abundant, than inT. fassoglensis2, while that for IPWC normally are much fainter. In addition, inT. fassoglensis, T. fassoglensis1, andT. esculentum,the band expected for IPWI appears much brighter than that for IPWC, except for itsycf3-trnSGGA-rps4region, which may be a result of high primer specificity.

FIGURE 3.Isomeric plastomes inTylosemaspecies.(A)Gene adjacency at the inversion breakpoints in the IPWI-type plastome.(B)Gene adjacency at inversion breakpoints in the IPWC-type plastome.(C)The results of our read-mapping analysis are depicted as numbers of paired-end reads spanning the 29-bp IR in the outer (total number of reads) and inner circles (proportion of matched reads to total mapped reads).(D)PCR amplicons of four breakpoint regions in four individuals ofTylosema(1,T. fassoglensis;2,T. fassoglensis1; 3,T. fassoglensis2; 4,T. esculentum). The white arrow highlights an abnormal result that may be caused by poor primer specificity. Red lines inAandBrefer to the 38-kb inverted segments. “M” inDrefers to a 100 bp plus DNA ladder, with “500” and “1000” indicating fragment lengths of 500 and 1 kb, respectively.

Plastid Phylogeny of Cercidoideae

Our phylogenetic analyses supported the monophyly of Cercidoideae with strong bootstrap support (BS) of 100% and contributed to clarifying intergeneric relationships (Supplementary Figure S2).Cercisis well-resolved as the first-branching lineage (BS = 100%), andAdenolobusis confidently placed as sister to the remaining Cercidoideae species (BS = 100%).BauhiniaandPiliostigmaare strongly supported as sister clades (BS ≥ 94%).Schnella, Barklya,andLysiphyllumform a clade with BS = 100%. However, our different data matrices produced conflicting relationships amongGriffonia(G), theBauhinia+Piliostigma(BP) clade, and the lineage containing the remaining species from a clade ofBarklya+Lysiphyllum+Schnella+Tylosema,hereafter: BLST). The matrices of original and GBLOCKS-edited CDS and all markers supportGriffoniaas sister to BP + BLST clade, while other matrices resolveGriffoniatogether withBauhiniaandPiliostigmaas sister to BLST. Incongruence was also found amongSchnella, BarklyaandLysiphyllumin different matrices, butSchnellaas sister toBarklyaandLysiphyllumwas the most strongly supported relationship.

Discussion

Structural Diversity of Plastomes in Cercidoideae

Our plastid genome analyses reveal various structural variations in Cercidoideae, including several inversions, shifts of IR-SC junction, and intron losses. Inversions and IR boundary shifts represent essential mechanisms for plastome rearrangements, which contribute to the structural diversification of plant plastomes (Wicke et al., 2011;Jansen and Ruhlman, 2012). Our study thus adds new results, because legume plastomes outside the Papilionoideae subfamily have long been considered to be conserved regarding their structure and gene content (Schwarz et al., 2015). We now can show that the evolutionary stasis of angiosperm plastomes breaks up already in early-branching lineages of Fabaceae, even though the two early-diverging Cercidoideae genera show no departures from the typical angiosperm plastome organization (Wang et al., 2017b). Major IR expansions and contractions plus some other structural variations such as inversions, gene duplications, and intron losses were also reported for mimosoids recently (Dugas et al., 2015;Wang et al., 2017a).

Inversions of over 1 kb in length are typical for papilionoid plastomes but rarely encountered in other legumes. No large inversions occur in plastomes of Caesalpinioideae (including mimosoids) and Detarioideae, and the unique 7.5-kb inversion has been identified in only one Cercidoideae species, as reported recently (Kim and Cullis, 2017). By analyzing additional genera of Cercidoideae, we here discover that a 7.5-kb inversion is restricted to examined species ofTylosemainstead of representing a synapomorphy for theBauhinias.l. group as speculated byKim and Cullis (2017).We also discover three more inversions in Cercidoideae, one of which, the 38-kb inversion inTylosema fassoglensis,appears to be directly mediated by a pair of 29-bp IRs, resembling the situation of the 36 and 39-kb inversions in Papilionoideae. The other inversions may be promoted by dispersed repeats in the breakpoint regions through intermolecular recombination (Jansen and Ruhlman, 2012). These newly discovered inversions considerably increase the complexity of plastome arrangements in the legume family, as indicated by a comparative analysis of genome structures across legumes (Supplementary Figure S3).

Large IR expansions and contractions are now known from numerous angiosperm lineages. In Fabaceae, the loss of the IRs in the IRLC papilionoids (including Cicereae, Fabeae, Galegeae s.l., Hedysareae, Millettieae p.p., Trifolieae, and a few allies likeCallerya, Glycyrrhiza,andOnonis) represents the extreme end of the spectrum of plastome rearrangements in legumes (Wojciechowski et al., 2000). IR expansion in Fabaceae has been reported first from the IREC clade (including Ingeae andAcacias.s.), which was named by a synapomorphic 13-kb IR expansion (Dugas et al., 2015;Wang et al., 2017a). In addition, IR-LSC junction shifts were found in two genera of IREC (Williams et al., 2015;Wang et al., 2017a). IR expansion into the SSC was also observed in the plastome ofTylosema esculentum,resulting in the duplication of the completeycf1gene (Kim and Cullis, 2017). Here, we show that IR-SC junction shifts also affectBauhinias.l., except forBauhiniaitself (Figure2). A double-strand break model (Goulding et al., 1996) and illegitimate recombination (Downie and Jansen, 2015;Blazier et al., 2016) may be causal for IR expansions and contractions in mimosoid plastomes (Wang et al., 2017a). The same mechanism may also underpin IR boundary shifts in Cercidoideae plastomes.

Isomeric Plastome inTylosemaspp.

The 29-bp IR-associated inversion we observed inT. fassoglensiswas also previously detected in some genistoids (Martin et al., 2014;Keller et al., 2017) as well as in aRobiniaspecies (Schwarz et al., 2015), where it was thought to result from a flip-flop recombination event. As these 29-bp IRs, which lie at the 3′-ends oftrnSGCUandtrnSGGA,universally exist in almost all legume plastomes, it can be expected that the inversion between this pair of IRs might have occurred or may occur time and again in other legume plastomes through the same mechanism (Martin et al., 2014). Thus, flip-flop recombination may also explain the 29-bp IR-mediated 38-kb inversion inT. fassoglensis.

Interestingly, the plastome with this inversion appears to be an isomeric plastome (IPWI) that coexists with the canonical type (IPWC) in each individual ofTylosema(Figure3). Isomeric plastomes, a result of flip-flop recombination, have been observed in several cupressophytes (Yi et al., 2013;Guo et al., 2014;Hsu et al., 2016;Qu et al., 2017b). Thus far, no isomeric plastomes have been reported in legumes, although two stable plastome configurations relating to a 45-kb inversion between a pair of imperfect repeats were found in different individuals ofMedicago truncatula(Gurdon and Maliga, 2014). Here, we observed two arrangements of isomeric plastomes in four differentTylosemataxa. IPWI is the dominating conformation over IPWC inT. fassoglensis(the sequenced individual), based on both read-mapping and PCR results. PCR screens also confirmed the domination of IPWI inT. fassoglensis1 as well as inT. esculentum.On the contrary, the IPWC dominates over IPWI inT. fassoglensis2. In sum, our results illustrate that isomeric plastomes not only coexist in all of the examined taxa ofTylosema,but the proportions of their relative conformations may be individual-specific. These findings, therefore, provide essential, new insights into the complexity of plastomes in the legume family. Still, further study is needed to explore isomeric plastomes in otherTylosemaspecies and legumes in general, and to clarify the molecular-evolutionary mechanisms and their relevance.

Phylogenetic Relationships in Cercidoideae

Several intergeneric relationships within Cercidoideae are hard to resolve (Bruneau et al., 2008;Sinou et al., 2009;LPWG, 2013,2017). The sister relationship betweenAdenolobusand the remaining genera of Cercidoideae (except for the basalCercis) were all weakly supported in these studies.Sinou et al. (2009)conducted a relatively dense-sampled phylogenetic study of this subfamily. In their work, the phylogenetic relationships ofGriffonia,the Clade 1 ofBauhinias.l. (represented by a clade ofBarklya+Lysiphyllum+Schnella+Tylosemain our study), and the Clade 2 ofBauhinias.l. (Bauhinia+Piliostigmaherein) were unresolved. Our plastome data also failed to clarify the phylogenetic relationship of these three groups but allowed resolving most intergeneric relationships among the sampled genera (Figure4and Supplementary Figure S2). Plastid phylogenomics has been successfully applied to resolve difficult relationships at the generic level (Ma et al., 2014;Givnish et al., 2015;Qu et al., 2017a;Zhang et al., 2017). However, the tree topology might not hold up when the second largest genusPhaneraand four other genera of this subfamily are included in a phylogenetic survey of Cercidoideae. Also, plastid phylogenomics might only resolve a uniparental evolutionary line, not necessarily reflecting the full coalescent history (Wicke and Schneeweiss, 2015). Future studies with an improved, denser taxon sampling in combination with data of other genomic compartments may provide enhanced resolution of the relationships among the genera of this subfamily.

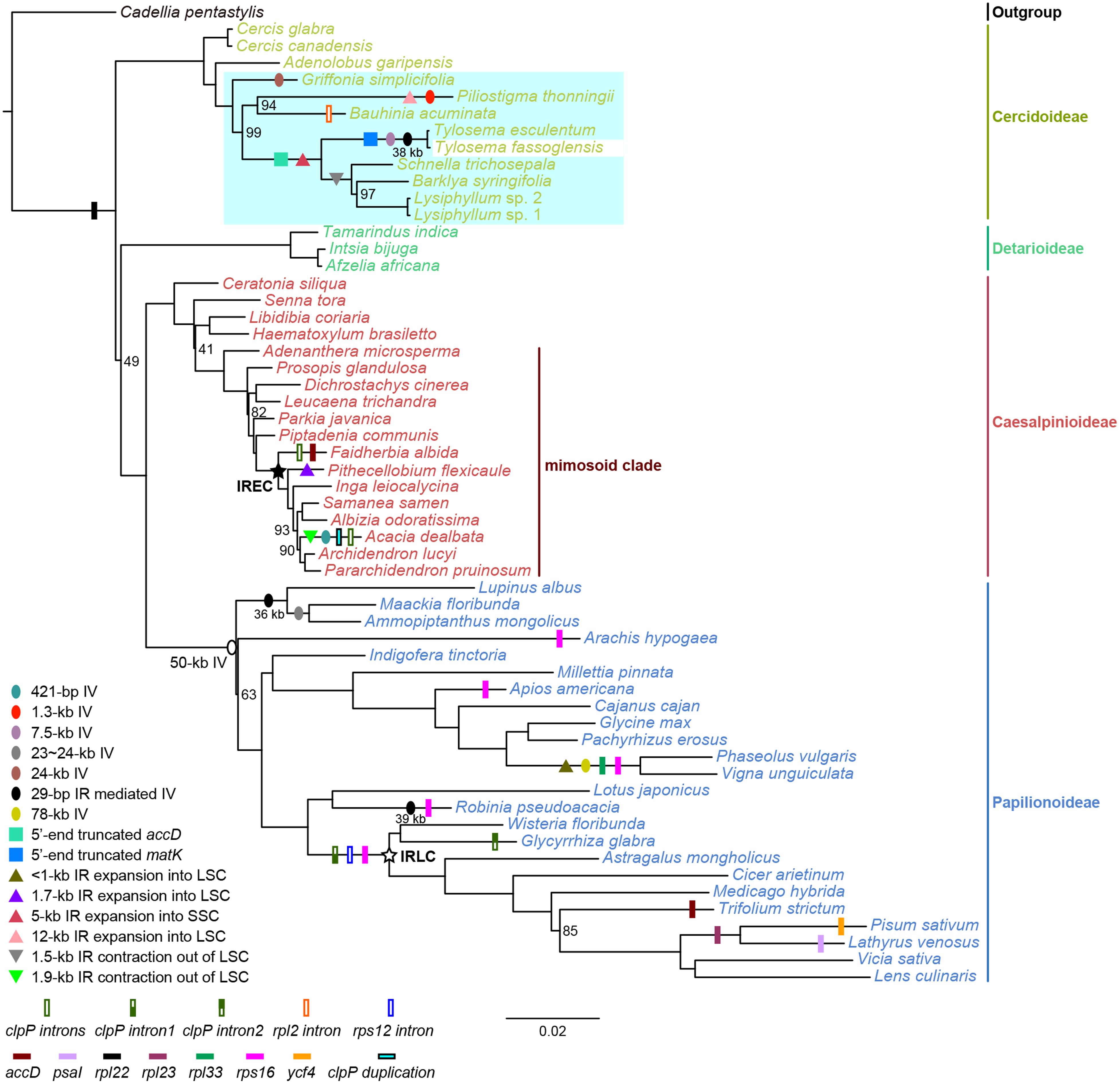

FIGURE 4.Maximum likelihood phylogeny reconstructed using a concatenated dataset of 77 plastid protein-coding genes and major plastome reconfigurations in legumes. The depicted ML tree was reconstructed from a concatenated dataset of 77 plastid protein-coding genes (CDS, Supplementary Figure S2). Species names are colored by their subfamily affiliation. Bootstrap support values of less than 100% are given at nodes. The scale bar indicates the mean number of nucleotide substitutions per site along a branch. As indicated in the legend at the bottom left, inversions (IV), functional, and physical gene losses, IR expansion/contraction, gene duplications, and intron losses are plotted onto branches using colored ovals, squares, triangles, and rectangles, respectively. Hollow circles and pentagons on nodes demarcate the most recent common ancestors of the 50-kb inversion clade, the IR-lacking clade (IRLC), and the IR expanding clade (IREC), respectively. Lengths of 29-bp IR mediated inversions are given below black ovals. A blue-shaded area highlights the plastome variations found in the species sequenced herein, while shown structural features other than these are summarized as reported byBruneau et al. (1990);Schwarz et al. (2015),Choi and Choi (2017),andWang et al. (2017a).

Evolutionary Pattern of Plastome Variations in Legumes

The plastidaccDgene encodes the β-carboxyl transferase subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase). It is essential for plants but has been lost independently in at least six photosynthetic angiosperm lineages (Gurdon and Maliga, 2014). In some legume species, the plastidaccDwas reported to have been functionally transferred to the nucleus (Magee et al., 2010;Sabir et al., 2014), allowing the non-functionalization of the plastid copy. The highly divergent 5′-end ofaccDinPisum(Doyle et al., 1995) may be as much a result of the non-functionalization of plastidaccDas the 5′-end truncation of CercidoideaeaccDwe have reported here. ThematKgene encodes an intron maturase, which has never been found to be a pseudogene or even absent from the plastome of a photosynthetic land plant (Zoschke et al., 2010;Wicke et al., 2011). We found that inTylosema,thematKgene lacks more than 100 bp at its 5′-end although it still constitutes an intact open reading frame. As in other legumes,Tylosemaretains the same set of group IIA-introns, which are usually associated with theMatkprotein during splicing (Zoschke et al., 2010). In some Orobanchaceae, a truncation atmatK’s 5′-end results in the use of an alternative start codon that restores the maturase function (Wolfe et al., 1992;Wicke et al., 2013). More research is needed to experimentally validate whetheraccDandmatKare still functioning inTylosema.

As mentioned earlier, many other structural plastome features have been reported as useful characters to support phylogenetic relationships in legumes (Figure4). Here, we have shown that a shorteraccDmay be a synapomorphy of the clade containingBarklya, Lysiphyllum, Schnella,andTylosema.A 5′-truncation ofmatKa 7.5-kb and a 29-bp IR-mediated 38-kb inversions characterizeTylosemaplastomes.TylosemaandSchnellashare a 5-kb IR expansion, which might have been ancestral to the entire clade, but which has lost fromBarklyaandLysiphyllum.On the other hand, the 1.5-kb IR contraction we reported herein represents a synapomorphic character of theBarklya+Lysiphyllum+Schnellaclade.

There are also many independent or parallel losses of genes or introns, inversions, and IR boundary shifts in legumes (Figure4). In Cercidoideae, the 1.3 and 24-kb inversions are probably autapomorphies ofPiliostigma thonningiiandGriffonia simplicifolia,respectively, and the 12-kb IR expansion into the LSC may be another putative autapomorphy ofP. thonningii.A denser sampling is needed to verify if these unusual plastome rearrangements are synapomorphic for certain lineages.

The loss of therpl2intron has been reported in at least 18 angiosperm families and is thought to be a potentially useful phylogenetic character (Downie et al., 1991;Kelchner, 2002;Judd et al., 2008;Dong et al., 2016;Gu et al., 2016). In Fabaceae, the intron ofrpl2lost several times independently in papilionoids, someBauhiniaspecies, andP. thonningii(Doyle et al., 1995;Lai et al., 1997;Sinou et al., 2009). Our study revealed thatBauhinia acuminatahas lost therpl2intron as well, thus corroborating the findings ofLai et al. (1997).However, we detected therpl2intron inP. thonningii,a finding inconsistent with earlier reports (Sinou et al., 2009). Therefore, we believe that further research with an expanded sampling is urgently needed to determine the number ofrpl2intron losses in legumes and to evaluate its phylogenetic relevance.

Author Contributions

Y-HW, T-SY, D-ZL, and HW designed this research. Y-HW conducted the experiments and analyses. S-DZ collected some species and extracted DNA. J-JJ and S-YC assembled the plastomes. Y-HW, T-SY, and SW wrote the manuscript, and all authors revised it.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key Basic Research Programme of China (2014CB954100), the National Science and Technology on Basic Research Programme (2013FY112600), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDPB0201), and the Large-scale Scientific Facilities of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. 2017-LSF-GBOWS-02).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the abovementioned funding sources. We would like to thank the Brisbane Botanic Garden (Australia) and Kunming Botanic Garden (China) for providing fresh plant material, Prof. Michelle van der Bank (African Centre for DNA Barcoding, South Africa) and Luciano Paganucci de Queiroz (Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Brazil), as well as Sina M. Omosowon (Imperial College London, United Kingdom), for their contribution of silica-dried plant materials. All experiments for this study were carried out in the Key Laboratory of the Southwest China Germplasm Bank of Wild Species at the Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. We would like to acknowledge the dedicated assistance of all staff members of this laboratory. We also thank the two reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, and their recognition of this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at:https:// frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00138/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., and Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool.J. Mol. Biol.215, 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Blazier, J. C., Jansen, R. K., Mower, J. P., Govindu, M., Zhang, J., Weng, M. L., et al. (2016). Variable presence of the inverted repeat and plastome stability inErodium.Ann. Bot.117, 1209–1220. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw065

Bruneau, A., Doyle, J. J., and Palmer, J. D. (1990). A chloroplast DNA inversion as a subtribal character in the Phaseoleae (Leguminosae).Syst. Bot.15, 378–386. doi: 10.2307/2419351

Bruneau, A., Forest, F., Herendeen, P. S., Klitgaard, B. B., and Lewis, G. P. (2001). Phylogenetic relationships in the Caesalpinioideae (Leguminosae) as inferred from chloroplasttrnLintron sequences.Syst. Bot.26, 487–514.

Bruneau, A., Mercure, M., Lewis, G. P., and Herendeen, P. S. (2008). Phylogenetic patterns and diversification in the caesalpinioid legumes.Botany86, 697–718. doi: 10.1139/B08-058

Cai, Z. Q., Guisinger, M., Kim, H. G., Ruck, E., Blazier, J. C., McMurtry, V., et al. (2008). Extensive reorganization of the plastid genome ofTrifolium subterraneum(Fabaceae) is associated with numerous repeated sequences and novel DNA insertions.J. Mol. Evol.67, 696–704. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9180-7

Castresana, J. (2000). Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis.Mol. Biol. Evol.17, 540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334

Choi, I. S., and Choi, B. H. (2017). The distinct plastid genome structure ofMaackia fauriei(Fabaceae: Papilionoideae) and its systematic implications for genistoids and tribe Sophoreae.PLOS ONE12:e0173766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173766

Chumley, T. W., Palmer, J. D., Mower, J. P., Fourcade, H. M., Calie, P. J., Boore, J. L., et al. (2006). The complete chloroplast genome sequence ofPelargonium x hortorum:organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants.Mol. Biol. Evol.23, 2175–2190. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl089

Clark, R. P., Mackinder, B. A., and Banks, H. (2017).Cheniellagen. nov. (Leguminosae: Cercidoideae) from southern China, Indochina and Malesia.Eur. J. Taxon.360, 1–37. doi: 10.5852/ejt.2017.360

Cosner, M. E., Raubeson, L. A., and Jansen, R. K. (2004). Chloroplast DNA rearrangements in Campanulaceae: Phylogenetic utility of highly rearranged genomes.BMC Evol. Biol.4:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-27

Darling, A. E., Mau, B., and Perna, N. T. (2010). progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement.PLOS ONE5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147

Dong, W. P., Xu, C., Li, D. Z., Jin, X. B., Li, R. L., Lu, Q., et al. (2016). Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome sequences in psammophyticHaloxylonspecies (Amaranthaceae).PeerJ4:e2699. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2699

Donkpegan, A. S. L., Doucet, J.-L., Migliore, J., Duminil, J., Dainou, K., Piñeiro, R., et al. (2017). Evolution in African tropical trees displaying ploidy-habitat association: The genusAfzelia(Leguminosae).Mol. Phylogenet. Evol107, 270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.11.004

Downie, S. R., and Jansen, R. K. (2015). A comparative analysis of whole plastid genomes from the Apiales: expansion and contraction of the inverted repeat, mitochondrial to plastid transfer of DNA, and identification of highly divergent noncoding regions.Syst. Bot.40, 336–351. doi: 10.1600/036364415X686620

Downie, S. R., Olmstead, R. G., Zurawski, G., Soltis, D. E., Soltis, P. S., Watson, J. C., et al. (1991). Six independent losses of the chloroplast DNArpl2intron in dicotyledons: molecular and phylogenetic implications.Evolution45, 1245–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb04390.x

Doyle, J. J., Doyle, J. L., Ballenger, J. A., and Palmer, J. D. (1996). The distribution and phylogenetic significance of a 50-kb chloroplast DNA inversion in the flowering plant family Leguminosae.Mol. Phylogen. Evol.5, 429–438. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0038

Doyle, J. J., Doyle, J. L., and Palmer, J. D. (1995). Multiple independent losses of two genes and one intron from legume.Syst. Bot.20, 272–294. doi: 10.2307/2419496

Dugas, D. V., Hernandez, D., Koenen, E. J. M., Schwarz, E., Straub, S., Hughes, C. E., et al. (2015). Mimosoid legume plastome evolution: IR expansion, tandem repeat expansions, and accelerated rate of evolution inclpP.Sci. Rep.5:16958. doi: 10.1038/srep16958

Feng, L., Gu, L. F., Luo, J., Fu, A. S., Ding, Q., Yiu, S. M., et al. (2017). Complete plastid genomes of the genusAmmopiptanthusand identification of a novel 23-kb rearrangement.Conserv. Genet. Resour.9, 647–650. doi: 10.1007/s12686-017-0747-8

Gantt, J. S., Baldauf, S. L., Calie, P. J., Weeden, N. F., and Palmer, J. D. (1991). Transfer ofrpl22to the nucleus greatly preceded its loss from the chloroplast and involved the gain of an intron.EMBO J.10, 3073–3078.

Givnish, T. J., Spalink, D., Ames, M., Lyon, S. P., Hunter, S. J., Zuluaga, A., et al. (2015). Orchid phylogenomics and multiple drivers of their extraordinary diversification.Proc. R. Soc. B.282, 1–10. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1553

Goulding, S. E., Olmstead, R. G., Morden, C. W., and Wolfe, K. H. (1996). Ebb and flow of the chloroplast inverted repeat.Mol. Gen. Genet.252, 195–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02173220

Gu, C., Tembrock, L. R., Johnson, N. G., Simmons, M. P., and Wu, Z. (2016). The complete plastid genome ofLagerstroemia faurieiand loss ofrpl2intron fromLagerstroemia(Lythraceae).PLOS ONE11:e0150752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150752

Guisinger, M. M., Kuehl, J. V., Boore, J. L., and Jansen, R. K. (2011). Extreme reconfiguration of plastid genomes in the angiosperm family Geraniaceae: Rearrangements, repeats, and codon usage.Mol. Biol. Evol.28, 583–600. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq229

Guo, W., Grewe, F., Cobo-Clark, A., Fan, W., Duan, Z., Adams, R. P., et al. (2014). Predominant and substoichiometric isomers of the plastid genome coexist withinJuniperusplants and have shifted multiple times during cupressophyte evolution.Genome Biol. Evol.6, 580–590. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu046

Guo, X. W., Castillo-Ramirez, S., Gonzalez, V., Bustos, P., Fernandez-Vazquez, J. L., Santamaria, R. I., et al. (2007). Rapid evolutionary change of common bean (Phaseolus vulgarisL.) plastome, and the genomic diversification of legume chloroplasts.BMC Genomics8:228. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-228

Gurdon, C., and Maliga, P. (2014). Two distinct plastid genome configurations and unprecedented intraspecies length variation in theaccDcoding region inMedicago truncatula.DNA Res.21, 417–427. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsu007

Haberle, R. C., Fourcade, H. M., Boore, J. L., and Jansen, R. K. (2008). Extensive rearrangements in the chloroplast genome ofTrachelium caeruleumare associated with repeats and tRNA genes.J. Mol. Evol.66, 350–361. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9086-4

Herendeen, P., Bruneau, A., and Lewis, G. (2003). “Phylogenetic relationships in caesalpinioid legumes: a preliminary analysis based on morphological and molecular data,” inAdvances in Legume Systematics, part 10, Higher Level Systematics,eds B. B. Klitgaard and A. Bruneau (Richmond: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), 37–62.

Hsu, C. Y., Wu, C. S., and Chaw, S. M. (2016). Birth of four chimeric plastid gene clusters in Japanese umbrella pine.Genome Biol. Evol.8, 1776–1784. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw109

Jansen, R. K., and Ruhlman, T. A. (2012). “Plastid genomes of seed plants,” inGenomics of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria,eds R. Bock and V. Knoop (Dordrecht: Springer), 103–126.

Jansen, R. K., Wojciechowski, M. F., Sanniyasi, E., Lee, S. B., and Daniell, H. (2008). Complete plastid genome sequence of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and the phylogenetic distribution ofrps12andclpPintron losses among legumes (Leguminosae).Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.48, 1204–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.06.013

Judd, W. S., Campbell, C. S., Kellogg, E. A., Stevens, P. F., and Donoghue, M. J. (2008).Plant Systematics: A Phylogenetic Approach,Third Edn. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Kato, T., Kaneko, T., Sato, S., Nakamura, Y., and Tabata, S. (2000). Complete structure of the chloroplast genome of a legume,Lotus japonicus.DNA Res.7, 323–330. doi: 10.1093/dnares/7.6.323

Katoh, K., and Standley, D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability.Mol. Biol. Evol.30, 772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010

Kazakoff, S. H., Imelfort, M., Edwards, D., Koehorst, J., Biswas, B., Batley, J., et al. (2012). Capturing the biofuel wellhead and powerhouse: the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of the leguminous feedstock treePongamia pinnata.PLOS ONE7:e51687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051687

Kelchner, S. A. (2002). Group II introns as phylogenetic tools: structure function, and evolutionary constraints.Am. J. Bot.89, 1651–1669. doi: 10.3732/ajb.89.10.1651

Keller, J., Rousseau-Gueutin, M., Martin, G. E., Morice, J., Boutte, J., Coissac, E., et al. (2017). The evolutionary fate of the chloroplast and nuclearrps16genes as revealed through the sequencing and comparative analyses of four novel legume chloroplast genomes fromLupinus.DNA Res.24, 343–358. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsx006

Kim, Y., and Cullis, C. (2017). A novel inversion in the chloroplast genome of marama (Tylosema esculentum).J. Exp. Bot.68, 2065–2072. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw500

Lai, M., Sceppa, J., Ballenger, J. A., Doyle, J. J., and Wunderlin, R. P. (1997). Polymorphism for the presence of therpL2intron in chloroplast genomes ofBauhinia(Leguminosae).Syst. Bot.22, 519–528. doi: 10.2307/2419825

Langmead, B., and Salzberg, S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2.Nat. Methods9, 357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923

Lee, H. L., Jansen, R. K., Chumley, T. W., and Kim, K. J. (2007). Gene relocations within chloroplast genomes ofJasminumandMenodora(Oleaceae) are due to multiple, overlapping inversions.Mol. Biol. Evol.24, 1161–1180. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm036

Lei, W., Ni, D., Wang, Y., Shao, J., Wang, X., Yang, D., et al. (2016). Intraspecific and heteroplasmic variations, gene losses and inversions in the chloroplast genome ofAstragalus membranaceus.Sci. Rep.6:21669. doi: 10.1038/srep21669

Lewis, G. P., Schrire, B. D., Mackinder, B. A., and Lock, M. (2005).Legumes of the World.Richmond: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Lohse, M., Drechsel, O., Kahlau, S., and Bock, R. (2013). OrganellarGenomeDRAW-a suite of tools for generating physical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes and visualizing expression data sets.Nucleic Acids Res.41, W575–W581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt289

LPWG (2013). Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades.Taxon62, 217–248. doi: 10.12705/622.8

LPWG (2017). A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny.Taxon66, 44–77. doi: 10.12705/661.3

Ma, P. F., Zhang, Y. X., Zeng, C. X., Guo, Z. H., and Li, D. Z. (2014). Chloroplast phylogenomic analyses resolve deep-level relationships of an intractable bamboo tribe Arundinarieae (poaceae).Syst. Biol.63, 933–950. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syu054

Magee, A. M., Aspinall, S., Rice, D. W., Cusack, B. P., Semon, M., Perry, A. S., et al. (2010). Localized hypermutation and associated gene losses in legume chloroplast genomes.Genome Res.20, 1700–1710. doi: 10.1101/gr.111955.110

Martin, G. E., Rousseau-Gueutin, M., Cordonnier, S., Lima, O., Michon-Coudouel, S., Naquin, D., et al. (2014). The first complete chloroplast genome of the Genistoid legumeLupinus luteus:evidence for a novel major lineage-specific rearrangement and new insights regarding plastome evolution in the legume family.Ann. Bot.113, 1197–1210. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu050

Milligan, B. G., Hampton, J. N., and Palmer, J. D. (1989). Dispersed repeats and structural reorganization in subclover chloroplast DNA.Mol. Biol. Evol.6, 355–368.

Palmer, J. D. (1983). Chloroplast DNA exists in two orientations.Nature301, 92–93. doi: 10.1038/301092a0

Palmer, J. D., Osorio, B., Aldrich, J., and Thompson, W. F. (1987). Chloroplast DNA evolution among legumes - loss of a large inverted repeat occurred prior to other sequence rearrangements.Curr. Genet.11, 275–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00355401

Palmer, J. D., and Thompson, W. F. (1982). Chloroplast DNA rearrangements are more frequent when a large inverted repeat sequence is lost.Cell29, 537–550. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90170-2

Patel, R. K., and Jain, M. (2012). NGS QC toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data.PLOS ONE7:e30619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619

Qu, X. J., Jin, J. J., Chaw, S. M., Li, D. Z., and Yi, T. S. (2017a). Multiple measures could alleviate long-branch attraction in phylogenomic reconstruction of Cupressoideae (Cupressaceae).Sci. Rep.7:41005. doi: 10.1038/srep41005

Qu, X. J., Wu, C. S., Chaw, S. M., and Yi, T. S. (2017b). Insights into the existence of isomeric plastomes in Cupressoideae (Cupressaceae).Genome Biol. Evol.9, 1110–1119. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx071

Ruhlman, T. A., and Jansen, R. K. (2014). “The plastid genomes of flowering plants,” inChloroplast Biotechnology: Methods and Protocols,ed. M. Pal (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press), 3–38.

Sabir, J., Schwarz, E., Ellison, N., Zhang, J., Baeshen, N. A., Mutwakil, M., et al. (2014). Evolutionary and biotechnology implications of plastid genome variation in the inverted-repeat-lacking clade of legumes.Plant Biotechnol. J.12, 743–754. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12179

Saski, C., Lee, S.-B., Daniell, H., Wood, T. C., Tomkins, J., Kim, H.-G., et al. (2005). Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Glycine max and comparative analyses with other legume genomes.Plant Mol. Biol.59, 309–322. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-8882-0

Schattner, P., Brooks, A. N., and Lowe, T. M. (2005). The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs.Nucleic Acids Res.33, W686–W689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366

Schwarz, E. N., Ruhlman, T. A., Sabir, J. S. M., Hajarah, N. H., Alharbi, N. S., Al-Malki, A. L., et al. (2015). Plastid genome sequences of legumes reveal parallel inversions and multiple losses ofrps16in papilionoids.J. Syst. Evol.53, 458–468. doi: 10.1111/jse.12179

Sinou, C., Forest, F., Lewis, G. P., and Bruneau, A. (2009). The genusBauhinias.l. (Leguminosae): a phylogeny based on the plastidtrnL–trnFregion.Botany87, 947–960. doi: 10.1139/B09-065

Stamatakis, A. (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies.Bioinformatics30, 1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033

Stein, D. B., Palmer, J. D., and Thompson, W. F. (1986). Structural evolution and flip-flop recombination of chloroplast DNA in the fern genusOsmunda.Curr. Genet.10, 835–841. doi: 10.1007/BF00418530

Sveinsson, S., and Cronk, Q. (2014). Evolutionary origin of highly repetitive plastid genomes within the clover genus (Trifolium).BMC Evol. Biol.14:228. doi: 10.1186/s12862-014-0228-6

Talavera, G., and Castresana, J. (2007). Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments.Syst. Biol.56, 564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164

Tsumura, Y., Suyama, Y., and Yoshimura, K. (2000). Chloroplast DNA inversion polymorphism in populations ofAbiesandTsuga.Mol. Biol. Evol.17, 1302–1312. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026414

Wang, Y. H., Qu, X. J., Chen, S. Y., Li, D. Z., and Yi, T. S. (2017a). Plastomes of Mimosoideae: structural and size variation, sequence divergence, and phylogenetic implication.Tree Genet. Genomes13:41. doi: 10.1007/s11295-017-1124-1

Wang, Y. H., Wang, H., Yi, T. S., and Wang, Y. H. (2017b). The complete chloroplast genomes ofAdenolobus garipensisandCercis glabra(Cercidoideae, Fabaceae).Conserv. Genet. Resour.9, 635–638. doi: 10.1007/s12686-017-0744-y

Weng, M. L., Blazier, J. C., Govindu, M., and Jansen, R. K. (2014). Reconstruction of the ancestral plastid genome in Geraniaceae reveals a correlation between genome rearrangements, repeats, and nucleotide substitution rates.Mol. Biol. Evol.31, 645–659. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst257

Wick, R. R., Schultz, M. B., Zobel, J., and Holt, K. E. (2015). Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies.Bioinformatics31, 3350–3352. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv383

Wicke, S., Muller, K. F., de Pamphilis, C. W., Quandt, D., Wickett, N. J., Zhang, Y., et al. (2013). Mechanisms of functional and physical genome reduction in photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic parasitic plants of the broomrape family.Plant Cell25, 3711–3725. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.113373

Wicke, S., and Schneeweiss, G. M. (2015). “Next-generation organellar genomics: potentials and pitfalls of high-throughput technologies for molecular evolutionary studies and plant systematics,” inNext-Generation Sequencing in Plant Systematics,eds E. Hörandl and M. S. Appelhans (Königstein: Koeltz Scientific Books), 9–50.

Wicke, S., Schneeweiss, G. M., dePamphilis, C. W., Muller, K. F., and Quandt, D. (2011). The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: Gene content, gene order, gene function.Plant Mol. Biol.76, 273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4

Williams, A. V., Boykin, L. M., Howell, K. A., Nevill, P. G., and Small, I. (2015). The complete sequence of theAcacia ligulatachloroplast genome reveals a highly divergentclpP1gene.PLOS ONE10:e0125768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125768

Wojciechowski, M. F., Sanderson, M. J., Steele, K. P., and Liston, A. (2000). “Molecular phylogeny of the “Temperate Herbaceous Tribes” of papilionoid legumes: a supertree approach,” inAdvances in Legume Systematics,part 9, eds P. S. Herendeen and A. Bruneau (Richmond: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), 277–298.

Wolfe, K. H., Morden, C. W., and Palmer, J. D. (1992). Function and evolution of a minimal plastid genome from a nonphotosynthetic parasitic plant.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.89, 10648–10652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10648

Wu, C. S., Lin, C. P., Hsu, C. Y., Wang, R. J., and Chaw, S. M. (2011). Comparative chloroplast genomes of Pinaceae: insights into the mechanism of diversified genomic organizations.Genome Biol. Evol.3, 309–319. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr026

Wyman, S. K., Jansen, R. K., and Boore, J. L. (2004). Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA.Bioinformatics20, 3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352

Yang, J. B., Li, D. Z., and Li, H. T. (2014). Highly effective sequencing whole chloroplast genomes of angiosperms by nine novel universal primer pairs.Mol. Ecol. Resour.14, 1024–1031. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12251

Yi, X., Gao, L., Wang, B., Su, Y. J., and Wang, T. (2013). The complete chloroplast genome sequence ofCephalotaxus oliveri(Cephalotaxaceae): evolutionary comparison ofCephalotaxuschloroplast DNAs and insights into the loss of inverted repeat copies in Gymnosperms.Genome Biol. Evol.5, 688–698. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt042

Zhang, S. D., Jin, J. J., Chen, S. Y., Chase, M. W., Soltis, D. E., Li, H. T., et al. (2017). Diversification of Rosaceae since the late cretaceous based on plastid phylogenomics.New Phytol.214, 1355–1367. doi: 10.1111/nph.14461

Zhang, T., Zeng, C. X., Yang, J. B., Li, H. T., and Li, D. Z. (2016). Fifteen novel universal primer pairs for sequencing whole chloroplast genomes and a primer pair for nuclear ribosomal DNAs.J. Syst. Evol.54, 219–227. doi: 10.1111/jse.12197

Keywords:inversion, isomeric plastomes, IR expansion/contraction, plastome, variation, Cercidoideae, Fabaceae

Citation:Wang Y-H, Wicke S, Wang H, Jin J-J, Chen S-Y, Zhang S-D, Li D-Z and Yi T-S (2018) Plastid Genome Evolution in the Early-Diverging Legume Subfamily Cercidoideae (Fabaceae).Front. Plant Sci.9:138. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00138

Received:17 November 2017;Accepted:24 January 2018;

Published:08 February 2018.

Edited by:

Federico Luebert,University of Bonn, GermanyReviewed by:

Anne Bruneau,Université de Montréal, CanadaMartin F. Wojciechowski,Arizona State University, United States

Copyright© 2018 Wang, Wicke, Wang, Jin, Chen, Zhang, Li and Yi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of theCreative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence:Ting-Shuang Yi,[email protected]De-Zhu Li,[email protected]

Yin-Huan Wang

Yin-Huan Wang Susann Wicke

Susann Wicke Hong Wang1

Hong Wang1 Jian-Jun Jin

Jian-Jun Jin De-Zhu Li

De-Zhu Li Ting-Shuang Yi

Ting-Shuang Yi