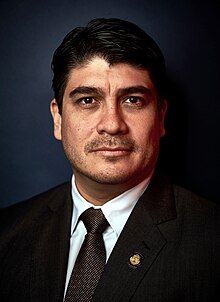

Carlos Andrés Alvarado Quesada(Spanish pronunciation:[ˈkaɾlosalβaˈɾaðokeˈsaða];born 14 January 1980) is a Costa Rican politician, writer, journalist, and political scientist who served as the 48th president ofCosta Rica[2]from 8 May 2018 to 8 May 2022. A member of theCitizens' Action Party(PAC), Alvarado previously served asMinister of Labor and Social Securityduring the presidency ofLuis Guillermo Solís.[3]

Carlos Alvarado Quesada | |

|---|---|

| |

| 48thPresident of Costa Rica | |

| In office 8 May 2018 – 8 May 2022 | |

| Vice President | Epsy Campbell Barr Marvin Rodríguez Cordero |

| Preceded by | Luis Guillermo Solís |

| Succeeded by | Rodrigo Chaves Robles |

| Minister of Labor and Social Security | |

| In office 28 March 2016 – 19 January 2017 | |

| President | Luis Guillermo Solís |

| Preceded by | Víctor Morales Mora |

| Succeeded by | Alfredo Hasbum Camacho |

| Minister of Human Development and Social Inclusion | |

| In office 10 July 2014 – 29 March 2016 | |

| President | Luis Guillermo Solís |

| Preceded by | Fernando Marín Rojas |

| Succeeded by | Emilio Arias Rodríguez |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Carlos Andrés Alvarado Quesada[1] 14 January 1980 San José, Costa Rica |

| Political party | Citizens' Action Party |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Gabriel |

| Education | University of Costa Rica(BA,MA) University of Sussex(MA) |

Alvarado, who was38 years old at the time of his presidential inauguration,became the youngest serving Costa Rican president sinceAlfredo González FloresWho took office in 1914 at the age of 36.

Education

editAlvarado holds abachelor's degreein communications and amaster's degreeinpolitical sciencefrom theUniversity of Costa Rica.He was aCheveningScholar from 2008 to 2009, earning a master's degree indevelopment studiesfrom the Institute of Development Studies at theUniversity of SussexinFalmer,England.[3][4]

Personal life

editAlvarado was born into a middle-class family in thePavas District,San José cantonin central Costa Rica, on 14 January 1980. His father,Alejandro Alvarado Induni,was an engineer, and his mother,Adelia Quesada Alvarado,was a homemaker. He has an older brother named Federico and a younger sister named Irene.[5]

Alvarado met his future wife,Claudia Dobles Camargo,while riding the school bus they both used to take to elementary school.[6]

Alvarado isRoman Catholic.[7]

Career

editLiterary career

editIn 2006, Alvarado Quesada published the anthology of storiesTranscripciones InfieleswithPerro Azul.[8]That same year, he obtained the Young Creation Award ofEditorial Costa Ricawith the novelLa Historia de Cornelius Brown.[8]In 2012, he published the historical novelLas Posesiones,which portrays the dark period in Costa Rican history when the government confiscated the properties ofGermansandItaliansduringWorld War II.[8]

Early political career

editHe served as an advisor to the Citizen Action Party's group in theLegislative Assembly of Costa Ricain the 2006-2010 period. He was a consultant to theInstitute of Development Studiesof theUnited Kingdomin financing SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises),[3]Department Manager of Dish Care & Air Care (Procter & GambleLatin America), Director of Communication for the presidential campaign ofLuis Guillermo Solís,professor in the School of Sciences of Collective Communication of theUniversity of Costa Ricaand the School of Journalism Of theUniversidad Latina de Costa Rica.[3]During the Solís Rivera administration, he served as Minister of Human Development and Social Inclusion and Executive President of theJoint Social Welfare Institute,the institution charged with combating poverty and giving state aid to the population with scarce resources. After the resignation ofVíctor Morales Moraas minister, Alvarado was appointedminister of Labor.[3][9]

President of Costa Rica (2018–2022)

editThis section has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Same-sex marriagewas a major issue in the campaign, after a ruling by theInter-American Court of Human Rightsrequired Costa Rica to recognize such unions.[10]Presidential candidateFabricio Alvarado Muñozcampaigned against same-sex marriage, while Alvarado Quesada argued to respect the court's ruling. On 1 April 2018, Alvarado Quesada won thepresidential election(second round) with 61%, defeating Alvarado Muñoz.[11]He was sworn into office on 8 May 2018.[12]

As president, Carlos Alvarado Quesada focused ondecarbonizingCosta Rica's economy. He set a goal for the country to achieve zero net emissions by the year 2050.[13]He planned to build an electric rail-based public transit system for the capital,San Josésince 40% of the country'sgreenhouse gas emissionscome from transportation.[14]On 24 February 2019, he launched a plan to fully decarbonize the country's economy, in a ceremony alongsideChristiana Figueres,the Costa Rican former UNFCCC head.[15]At this event, he described decarbonization as "the great challenge of our generation," and declared that "Costa Rica must be among the first countries to achieve it, if not the first."[16]

In December 2018, he pushed through a law that raised taxes and reduced public sector salaries, which he justified due to the country's poor economic situation. His actions resulted in the largest general strike in twenty years.[17]

During theCOVID-19 pandemic,he decided to maintain aneoliberaleconomic policy with high social costs. The government has thus cut public spending, especially in the education budget. Unemployment has risen from 8.1% in 2017 to 14.4% by the end of 2021, 23% of the population lives below the poverty line and the public debt has reached 70% of GDP, one of the highest rates in Latin America. While this policy was supported in Congress by theNational Liberation Party(PNL) and theSocial Christian Unity Party(PUSC), the two main traditional parties, it has caused the government to lose the support of civil servants, academics, the left, and a large part of the middle class. According toECLAC,Costa Rica is expected to be the Latin American country, along with Brazil, that will have the most difficulty in reviving its economy after the pandemic.[18][19]

The country's political life has been marked by corruption cases, both in government and in opposition parties, which have contributed to the discrediting of the political class among a part of the population. Ministers, former ministers, and mayors have been implicated in corruption cases involving embezzlement and bribery for multi-million dollar public works contracts. In 2021, six mayors, including the mayor of the capital San José, were arrested. Some cases even revealed the penetration of political circles bydrug traffickinggroups.[20]

At the end of Carlos Alvarado's presidential term, he had a twelve percent approval rating.[21]His successor,Rodrigo Chaves Robles,assumed office on 8 May 2022.

After the presidency

editDuring his government, Alvarado combined his national activities with his participation in international events, both in-person and virtual, on Costa Rica's global positioning as a leading nation in sustainability, energy, and climate change mitigation. Alvarado was invited by organizations such as Chatham House,[22]Atlantic Council,[23]and DC Dialogues, moderated byColumbia Universityprofessor and CNN en Español columnistGeovanny Vicente.[24][25]After his presidency, Alvarado continued with this academic agenda, serving as a keynote speaker for events at institutions such asHarvard University,[26]the Inter-American Investment and Nature Forum (IABNF), organized by the Inter-American Institute of Justice and Sustainability (IIJS), where he has shared the stage with international leaders likeClaudia S. de Windt,among others.[27][28]

Currently, he is a professor at the Graduate School of Global Affairs atTufts Universityin Massachusetts, United States.[29]

References

edit- ^Quesada, Andrés (7 May 2018)."Carlos Alvarado".El País(in Spanish).Retrieved15 August2019.

- ^"Carlos Alvarado Quesada | The Fletcher School".fletcher.tufts.edu.Retrieved3 May2024.

- ^abcde"Carlos Alvarado Quesada"(PDF).oecd.org.Retrieved28 March2017.

- ^IDS, University of Sussex and."IDS alumnus elected President of Costa Rica".The University of Sussex.Archived fromthe originalon 7 May 2018.Retrieved13 February2019.

- ^"Carlos Alvarado: President of Costa Rica, Journalist, Writer, Musician, Husband and Father".Costa Rica Star News.8 April 2018.Retrieved8 April2022.

- ^"La sancarleña que en un mes será la Primera Dama del país".San Carlos Digital.2 April 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 24 November 2018.Retrieved24 November2018.

- ^Gómez, Dylan (2 February 2019).""Soy creyente (…) soy católico y mi familia es muy católica", afirma Alvarado ante las críticas ".NCR.Retrieved27 May2020.

- ^abc"Carlos Alvarado Quesada".Editorial Costa Rica.Archived fromthe originalon 15 July 2020.Retrieved28 March2017.

- ^"Carlos Alvarado, actual presidente del IMAS, es el nuevo ministro de Trabajo".La Nación.Retrieved1 March2022.

- ^Henley, Jon (2 April 2018)."Costa Rica: Carlos Alvarado wins presidency in vote fought on gay rights".The Guardian.Retrieved3 July2018.

- ^David Alire Garcia; Enrique Andres Pretel (1 April 2018)."Costa Rica center-left easily wins presidency in vote fought on gay rights".Reuters.

- ^"Chevening Alumnus Carlos Alvarado becomes 48th president of Costa Rica | Chevening".Archived fromthe originalon 17 March 2022.Retrieved18 March2022.

- ^"Costa Rica Commits to Fully Decarbonize by 2050".United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.4 March 2019.Retrieved7 June2022.

- ^"Costa Rica launches 'unprecedented' push for zero emissions by 2050".Reuters.25 February 2019.Retrieved2 April2019.

- ^"Costa Rica launches plan to become the world's first decarbonized country".The Climate Group.25 February 2019. Archived fromthe originalon 27 July 2020.Retrieved2 April2019.

- ^"Costa Rica Commits to Fully Decarbonize by 2050 | UNFCCC".Unfccc.int.Retrieved2 April2019.

- ^"Costa Rica: Jornada de movilización en la segunda semana de huelga contra la reforma fiscal".Laizquierdadiario.com.

- ^"L'indécision domine l'électorat avant les élections au Costa Rica".Le Monde.6 February 2022.Retrieved1 March2022.

- ^"A Poorer Costa Rica, the Challenge of the Next Governor".Ticotimes.net.6 February 2022.Retrieved1 March2022.

- ^"L'indécision domine l'électorat avant les élections au Costa Rica".Le Monde.6 February 2022.Retrieved1 March2022.

- ^"Imagen de Carlos Alvarado llega a su punto más bajo en cuatro años y ahora un 72% tiene una opinión negativa de su gestión".Larepublica.net.Retrieved1 March2022.

- ^"In conversation with Carlos Alvarado Quesada".www.chathamhouse.org.3 November 2021.

- ^"Leaders of the Americas: A conversation with H.E. Carlos Alvarado, President of Costa Rica".

- ^"Prioritizing Biodiversity and Green Energy: A Conversation with President of Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado".

- ^"[:en]#DCDialogues: Prioritizing Biodiversity and Green Energy: A Conversation with President of Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado - NYU Washington DC[:es]#DCDialogues: Priorizando la Biodiversidad y la Energía Verde: Una Conversación con el Presidente de Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado - NYU Washington DC[:]".12 July 2024.

- ^"Former Costa Rican President Alvarado describes his country's public health successes".27 October 2022.

- ^"Inaugural IABNF 2023 sets biodiversity agenda".LatAm Investor.Retrieved20 September2024.

- ^"IABNF 2023 Speaker Lineup".

- ^"Carlos Alvarado Quesada | the Fletcher School".

External links

edit- Biography by CIDOB(in Spanish)