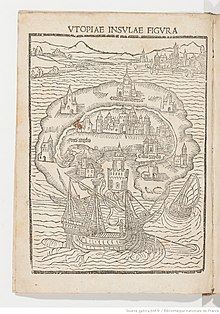

Autopia(/juːˈtoʊpiə/yoo-TOH-pee-ə) typically describes an imaginarycommunityorsocietythat possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members.[1]It was coined bySir Thomas Morefor his 1516 bookUtopia,which describes afictional islandsociety in theNew World.

Hypothetical utopias focus on, among other things, equality in categories such aseconomics,governmentandjustice,with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying according to ideology.[2]Lyman Tower Sargentargues that the nature of a utopia is inherently contradictory because societies are nothomogeneousand have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. To quote:

There are socialist, capitalist, monarchical, democratic, anarchist, ecological, feminist, patriarchal, egalitarian, hierarchical, racist, left-wing, right-wing, reformist, free love, nuclear family, extended family, gay, lesbian and many more utopias [Naturism,Nude Christians,...] Utopianism, some argue, is essential for the improvement of the human condition. But if used wrongly, it becomes dangerous. Utopia has an inherent contradictory nature here.

— Lyman Tower Sargent,Utopianism: A very short introduction(2010)[3]

The opposite of a utopia is adystopia.Utopian and dystopian fictionhas become a popular literary category. Despite being common parlance for something imaginary, utopianism inspired and was inspired by some reality-based fields and concepts such asarchitecture,file sharing,social networks,universal basic income,communes,open bordersand evenpirate bases.

Etymology and history

editThe wordutopiawas coined in 1516 fromAncient Greekby the EnglishmanSir Thomas Morefor his Latin textUtopia.It literally translates as "no place", coming from theGreek:οὐ( "not" ) and τόπος ( "place" ), and meant any non-existent society, when 'described in considerable detail'.[4]However, in standard usage, the word's meaning hasshiftedand now usually describes a non-existent society that is intended to be viewedas considerably betterthan contemporary society.[5]

In his original work, More carefully pointed out the similarity of the word toeutopia,meaning "good place", fromGreek:εὖ( "good" or "well" ) and τόπος ( "place" ), which ostensibly would be the more appropriate term for the concept in modern English. The pronunciations ofeutopiaandutopiainEnglishareidentical,which may have given rise to the change in meaning.[5][6]Dystopia,a term meaning "bad place" coined in 1868, draws on this latter meaning. The opposite of a utopia,dystopiais a concept which surpassedutopiain popularity in thefictional literaturefrom the 1950s onwards, chiefly because of the impact of George Orwell'sNineteen Eighty-Four.

In 1876, writerCharles Renouvierpublished a novel calledUchronia(FrenchUchronie).[7]Theneologism,usingchronosinstead oftopos,has since been used to refer to non-existent idealized times in fiction, such asPhilip Roth'sThe Plot Against America(2004),[8]andPhilip K. Dick'sThe Man in the High Castle(1962).[9]

According to thePhilosophical Dictionary,proto-utopian ideas begin as early as the period ofancient Greeceand Rome,medieval heretics,peasant revoltsand establish themselves in the period of the early capitalism,reformationandRenaissance(Hus,Müntzer,More,Campanella),democratic revolutions(Meslier,Morelly,Mably,Winstanley,laterBabeufists,Blanquists,) and in a period of turbulent development of capitalism that highlighted antagonisms ofcapitalist society(Saint-Simon,Fourier,Owen,Cabet,Lamennais,Proudhonand their followers).[10]

Definitions and interpretations

editFamous quotes from writers and characters about utopia:

- "There is nothing like a dream to create the future. Utopia to-day, flesh and blood tomorrow." —Victor Hugo

- "A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias." —Oscar Wilde

- "Utopias are often only premature truths." —Alphonse de Lamartine

- "None of theabstractconcepts comes closer to fulfilled utopia than that of eternal peace. "—Theodor W. Adorno

- "I think that there is always a part of utopia in any romantic relationship." —Pedro Almodovar

- "In ourselves alone the absolute light keeps shining, a sigillum falsi et sui, mortis et vitae aeternae [false signal and signal of eternal life and death itself], and the fantastic move to it begins: to the external interpretation of the daydream, the cosmic manipulation of a concept that is utopian in principle." —Ernst Bloch

- "When I die, I want to die in a Utopia that I have helped to build." —Henry Kuttner

- "A man must be far gone in Utopian speculations who can seriously doubt that if these [United] States should either be wholly disunited, or only united in partial confederacies, the subdivisions into which they might be thrown would have frequent and violent contests with each other." —Alexander Hamilton,FederalistNo. 6.

- "Most dictionaries associate utopia with ideal commonwealths, which they characterize as an empirical realization of an ideal life in an ideal society. Utopias, especially social utopias, are associated with the idea of social justice." – Lukáš Perný[11]

- "We are all utopians, so soon as we wish for something different." –Henri Lefebvre[12]

- "Every daring attempt to make a great change in existing conditions, every lofty vision of new possibilities for the human race, has been labeled Utopian." –Emma Goldman[13]

Utopian socialistÉtienne Cabetin his utopian bookThe Voyage to Icariacited the definition from the contemporaryDictionary of ethical and political sciences:

Utopias and other models of government, based on the public good, may be inconceivable because of the disordered human passions which, under the wrong governments, seek to highlight the poorly conceived or selfish interest of the community. But even though we find it impossible, they are ridiculous to sinful people whose sense of self-destruction prevents them from believing.

MarxandEngelsused the word "utopia" to denote unscientific social theories.[14]

PhilosopherSlavoj Žižektold about utopia:

Which means that we should reinvent utopia but in what sense. There are two false meanings of utopia one is this old notion of imagining this ideal society we know will never be realized, the other is the capitalist utopia in the sense of new perverse desire that you are not only allowed but even solicited to realize. The true utopia is when the situation is so without issue, without the way to resolve it within the coordinates of the possible that out of the pure urge of survival you have to invent a new space. Utopia is not kind of a freeimaginationutopia is a matter of inner most urgency, you are forced to imagine it, it is the only way out, and this is what we need today. "[15]

PhilosopherMilan Šimečkasaid:

...utopism was a common type of thinking at the dawn of humancivilization.We find utopian beliefs in the oldest religious imaginations, appear regularly in the neighborhood of ancient, yet pre-philosophical views on the causes and meaning of natural events, the purpose of creation, the path of good and evil, happiness and misfortune, fairy tales and legends later inspired by poetry and philosophy... the underlying motives on which utopian literature is built are as old as the entire historical epoch of human history.”[16]

PhilosopherRichard Stahelsaid:

...everysocial organizationrelies on something that is not realized or feasible, but has the ideal that is somewhere beyond the horizon, alighthouseto which it may seek to approach if it considers that ideal socially valid and generally accepted. "[17]

Varieties

editChronologically, the first recorded Utopian proposal isPlato'sRepublic.[18]Part conversation, part fictional depiction and part policy proposal,Republicwould categorize citizens into a rigid class structure of "golden," "silver," "bronze" and "iron" socioeconomic classes. The golden citizens are trained in a rigorous 50-year-long educational program to be benign oligarchs, the "philosopher-kings." Plato stressed this structure many times in statements, and in his published works, such as theRepublic.The wisdom of these rulers will supposedly eliminate poverty and deprivation through fairly distributed resources, though the details on how to do this are unclear. The educational program for the rulers is the central notion of the proposal. It has few laws, no lawyers and rarely sends its citizens to war but hiresmercenariesfrom among its war-prone neighbors. These mercenaries were deliberately sent into dangerous situations in the hope that the more warlike populations of all surrounding countries will be weeded out, leaving peaceful peoples to remain.

During the 16th century, Thomas More's bookUtopiaproposed an ideal society of the same name.[19]Readers, including Utopian socialists, have chosen to accept this imaginary society as the realistic blueprint for a working nation, while others have postulated that Thomas More intended nothing of the sort.[20]It is believed that More'sUtopiafunctions only on the level of a satire, a work intended to reveal more about theEnglandof his time than about an idealistic society.[21]This interpretation is bolstered by the title of the book and nation and its apparent confusion between the Greek for "no place" and "good place": "utopia" is a compound of the syllable ou-, meaning "no" and topos, meaning place. But thehomophonicprefix eu-, meaning "good," also resonates in the word, with the implication that the perfectly "good place" is really "no place."

Mythical and religious utopias

editIn many cultures, societies, and religions, there is some myth or memory of a distant past when humankind lived in a primitive and simple state but at the same time one of perfect happiness and fulfillment. In those days, the variousmythstell us, there was an instinctive harmony between humanity and nature. People's needs were few and their desires limited. Both were easily satisfied by the abundance provided by nature. Accordingly, there were no motives whatsoever for war or oppression. Nor was there any need for hard and painful work. Humans were simple andpiousand felt themselves close to their God or gods. According to one anthropological theory, hunter-gatherers were theoriginal affluent society.

These mythical or religious archetypes are inscribed in many cultures and resurge with special vitality when people are in difficult and critical times. However, in utopias, the projection of the myth does not take place towards the remote past but either towards the future or towards distant and fictional places, imagining that at some time in the future, at some point in space, or beyond death, there must exist the possibility of living happily.

In the United States and Europe, during theSecond Great Awakening(ca. 1790–1840) and thereafter, many radical religious groups formed utopian societies in whichfaithcould govern all aspects of members' lives. These utopian societies included theShakers,who originated in England in the 18th century and arrived in America in 1774. A number of religious utopian societies from Europe came to the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, including the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness (led byJohannes Kelpius(1667–1708), theEphrata Cloister(established in 1732) and theHarmony Society,among others. The Harmony Society was aChristian theosophyandpietistgroup founded inIptingen,Germany,in 1785. Due to religious persecution by theLutheran Churchand the government inWürttemberg,[22]the society moved to the United States on October 7, 1803, settling inPennsylvania.On February 15, 1805, about 400 followers formally organized the Harmony Society, placing all theirgoods in common.The group lasted until 1905, making it one of the longest-running financially successful communes in American history.

TheOneida Community,founded byJohn Humphrey NoyesinOneida, New York,was a utopian religiouscommunethat lasted from 1848 to 1881. Although this utopian experiment has become better known today for its manufacture of Oneida silverware, it was one of the longest-running communes in American history. TheAmana Colonieswere communal settlements inIowa,started by radical Germanpietists,which lasted from 1855 to 1932. TheAmana Corporation,manufacturer of refrigerators and household appliances, was originally started by the group. Other examples areFountain Grove(founded in 1875), Riker's Holy City and other Californian utopian colonies between 1855 and 1955 (Hine), as well asSointula[23]inBritish Columbia,Canada. TheAmishandHutteritescan also be considered an attempt towards religious utopia. A wide variety ofintentional communitieswith some type of faith-based ideas have also started across the world.

Anthropologist Richard Sosis examined 200 communes in the 19th-century United States, both religious and secular (mostlyutopian socialist). 39 percent of the religious communes were still functioning 20 years after their founding while only 6 percent of the secular communes were.[24]The number of costly sacrifices that a religious commune demanded from its members had a linear effect on its longevity, while in secular communes demands for costly sacrifices did not correlate with longevity and the majority of the secular communes failed within 8 years. Sosis cites anthropologistRoy Rappaportin arguing thatritualsand laws are more effective whensacralized.[25]Social psychologistJonathan Haidtcites Sosis's research in his 2012 bookThe Righteous Mindas the best evidence thatreligionis anadaptive solutionto thefree-rider problemby enablingcooperationwithoutkinship.[26]Evolutionary medicineresearcherRandolph M. Nesseand theoretical biologistMary Jane West-Eberhardhave argued instead that because humans withaltruistictendencies are preferred as social partners they receivefitness advantagesbysocial selection,[list 1]with Nesse arguing further that social selection enabled humans as a species to become extraordinarilycooperativeand capable of creatingculture.[31]

TheBook of Revelationin the ChristianBibledepicts aneschatologicaltime with the defeat ofSatan,ofEviland ofSin.The main difference compared to theOld Testamentpromisesis that such a defeat also has anontologicalvalue: "Then I saw 'anew heaven and a new earth,' for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea...'He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death' or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away "[32]and no longer justgnosiological(Isaiah:"See, I will create/new heavens and a new earth./The former things will not be remembered,/nor will they come to mind".[33][34][35]Narrow interpretation of the text depicts Heaven on Earth or a Heaven brought to Earth withoutsin.Daily and mundane details of this new Earth, where God andJesusrule, remain unclear, although it is implied to be similar to the biblical Garden of Eden. Some theological philosophers believe that heaven will not be a physical realm but instead anincorporealplace forsouls.[36]

Golden Age

editTheGreekpoetHesiod,around the 8th century BC, in his compilation of the mythological tradition (the poemWorks and Days), explained that, prior tothe present era,there were four other progressively less perfect ones, the oldest of which was theGolden Age.

Scheria

editPerhaps the oldest Utopia of which we know, as pointed out many years ago byMoses Finley,[37]isHomer'sScheria,island of thePhaeacians.[38]A mythical place, often equated with classicalCorcyra,(modernCorfu/Kerkyra), whereOdysseuswas washed ashore after 10 years of storm-tossed wandering and escorted to the King's palace by his daughterNausicaa.With stout walls, a stone temple and good harbours, it is perhaps the 'ideal'Greek colony,a model for those founded from the middle of the 8th Century onward. A land of plenty, home to expert mariners (with the self-navigating ships), and skilled craftswomen who live in peace under their king's rule and fear no strangers.

Plutarch,the Greek historian and biographer of the 1st century, dealt with the blissful and mythic past of humanity.

Arcadia

editFromSir Philip Sidney's prose romanceThe Old Arcadia(1580), originally a region in thePeloponnesus,Arcadiabecame asynonymfor any rural area that serves as apastoralsetting, alocus amoenus( "delightful place" ).

The Biblical Garden of Eden

editTheBiblicalGarden of Edenas depicted in theOld TestamentBible'sBook of Genesis2 (Authorized Version of 1611):

And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed. Out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food; thetree of lifealso in the midst of the garden and thetree of knowledge of good and evil.[...]

And the Lord God took the man and put him into the garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat: but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die. [...]

And the Lord God said, It is not good that the man should be alone; [...] And the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam and he slept: and he took one of his ribs and closed up the flesh instead thereof and the rib, which the Lord God had taken from man, made he a woman and brought her unto the man.

According to the exegesis that the biblical theologianHerbert Haagproposes in the bookIs original sin in Scripture?,[40]published soon after theSecond Vatican Council,Genesis 2:25 would indicate thatAdam and Evewere created from the beginning naked of thedivine grace,an originary grace that, then, they would never have had and even less would have lost due to the subsequent events narrated.[41]On the other hand, while supporting a continuity in the Bible about the absence ofpreternaturalgifts (Latin:dona praeternaturalia)[42]with regard to theophitic event,Haag never makes any reference to the discontinuity of the loss of access to the tree of life.

The Land of Cockaigne

editThe Land ofCockaigne(also Cockaygne, Cokaygne), was an imaginary land of idleness and luxury, famous in medieval stories and the subject of several poems, one of which, an early translation of a 13th-century French work, is given inGeorge Ellis'Specimens of Early English Poets.In this, "the houses were made of barley sugar and cakes, the streets were paved with pastry and the shops supplied goods for nothing." London has been so called (seeCockney) but Boileau applies the same to Paris.[43]Schlaraffenlandis an analogous German tradition. All these myths also express some hope that theidyllicstate of affairs they describe is not irretrievably and irrevocably lost to mankind, that it can be regained in some way or other.

One way might be a quest for an "earthly paradise" – a place likeShangri-La,hidden in theTibetanmountains and described byJames Hiltonin his utopian novelLost Horizon(1933).Christopher Columbusfollowed directly in this tradition in his belief that he had found the Garden of Eden when, towards the end of the 15th century, he first encountered theNew Worldand its indigenous inhabitants.[citation needed]

The Peach Blossom Spring

editThePeach Blossom Spring(Chinese:Đào hoa nguyên;pinyin:Táohuāyuán), a prose piece written by the Chinese poetTao Yuanming,describes a utopian place.[44][45]The narrative goes that a fisherman from Wuling sailed upstream a river and came across a beautiful blossoming peach grove and lush green fields covered with blossom petals.[46]Entranced by the beauty, he continued upstream and stumbled onto a small grotto when he reached the end of the river.[46]Though narrow at first, he was able to squeeze through the passage and discovered an ethereal utopia, where the people led an ideal existence in harmony with nature.[47]He saw a vast expanse of fertile lands, clear ponds, mulberry trees, bamboo groves and the like with a community of people of all ages and houses in neat rows.[47]The people explained that their ancestors escaped to this place during the civil unrest of theQin dynastyand they themselves had not left since or had contact with anyone from the outside.[48]They had not even heard of the later dynasties of bygone times or the then-currentJin dynasty.[48]In the story, the community was secluded and unaffected by the troubles of the outside world.[48]

The sense of timelessness was predominant in the story as a perfect utopian community remains unchanged, that is, it had no decline nor the need to improve.[48]Eventually, the Chinese termPeach Blossom Springcame to be synonymous for the concept of utopia.[49]

Datong

editDatong(Chinese:Đại đồng;pinyin:dàtóng) is a traditional Chinese Utopia. The main description of it is found in the ChineseClassic of Rites,in the chapter called "Li Yun" (Chinese:Lễ vận;pinyin:Lǐ yùn). Later, Datong and its ideal of 'The World Belongs to Everyone/The World is Held in Common' Tianxia weigong(Chinese:Thiên hạ vi công;pinyin:Tiānxià wèi gōng) influenced modern Chinese reformers and revolutionaries, such asKang Youwei.

Ketumati

editIt is said, onceMaitreyaisreborninto the future kingdom ofKetumati,a utopian age will commence.[50]The city is described inBuddhismas a domain filled with palaces made of gems and surrounded byKalpavrikshatrees producing goods. During its years, none of the inhabitants ofJambudvipawill need to take part in cultivation and hunger will no longer exist.[51]

Modern utopias

editIn the 21st century, discussions around utopia for some authors includepost-scarcity economics,late capitalism,anduniversal basic income;for example, the "human capitalism" utopia envisioned inUtopia for Realists(Rutger Bregman2016) includes a universal basic income and a 15-hourworkweek,along withopen borders.[52]

Scandinavian nations,which as of 2019 ranked at the top of theWorld Happiness Report,are sometimes cited as modern utopias, although British authorMichael Boothhas called that a myth and wrote a2014 book about the Nordic countries.[53]

Economics

editParticularly in the early 19th century, several utopian ideas arose, often in response to the belief that social disruption was created and caused by the development ofcommercialismandcapitalism.These ideas are often grouped in a greater "utopian socialist" movement, due to their shared characteristics. A once common characteristic is anegalitariandistribution of goods, frequently with the total abolition ofmoney.Citizens only doworkwhich they enjoy and which is for thecommon good,leaving them with ample time for the cultivation of the arts and sciences. One classic example of such a utopia appears inEdward Bellamy's 1888 novelLooking Backward.William Morrisdepicts another socialist utopia in his 1890 novelNews from Nowhere,written partially in response to the top-down (bureaucratic) nature of Bellamy's utopia, which Morris criticized. However, as the socialist movement developed, it moved away from utopianism;Marxin particular became a harsh critic of earlier socialism which he described as "utopian". (For more information, see theHistory of Socialismarticle.) In a materialist utopian society, the economy is perfect; there is no inflation and only perfect social and financial equality exists.

Edward Gibbon Wakefield's utopian theorizing on systematiccolonialsettlementpolicy in the early-19th century also centred on economic considerations, but with a view to preserving class distinctions;[54] Wakefield influenced several colonies founded inNew ZealandandAustraliain the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s.

In 1905,H. G. WellspublishedA Modern Utopia,which was widely read and admired and provoked much discussion. Also considerEric Frank Russell's bookThe Great Explosion(1963), the last section of which details an economic and social utopia. This forms the first mention of the idea ofLocal Exchange Trading Systems(LETS).

During the "Khrushchev Thaw"period,[55]the Soviet writerIvan Efremovproduced the science-fiction utopiaAndromeda(1957) in which a major cultural thaw took place: humanity communicates with a galaxy-wide Great Circle and develops its technology and culture within a social framework characterized by vigorous competition between alternative philosophies.

The English political philosopherJames Harrington(1611–1677), author of the utopian workThe Commonwealth of Oceana,published in 1656, inspired Englishcountry-partyrepublicanism (1680s to 1740s) and became influential in the design of three American colonies. His theories ultimately contributed to the idealistic principles of the American Founders. The colonies ofCarolina(founded in 1670),Pennsylvania(founded in 1681), andGeorgia(founded in 1733) were the only three English colonies in America that were planned as utopian societies with an integrated physical, economic and social design. At the heart of the plan for Georgia was a concept of "agrarian equality" in which land was allocated equally and additional land acquisition through purchase or inheritance was prohibited; the plan was an early step toward theyeomanrepublic later envisioned byThomas Jefferson.[56][57][58]

Thecommunesof the 1960s in the United States often represented an attempt to greatly improve the way humans live together in communities. Theback-to-the-landmovements andhippiesinspired many to try to live in peace and harmony on farms or in remote areas and to set up new types of governance.[59]Communes likeKaliflower,which existed between 1967 and 1973, attempted to live outside of society's norms and to create their own idealcommunalistsociety.[60][61]

People all over the world organized and builtintentional communitieswith the hope of developing a better way of living together. Many of these intentional communities are relatively small. Many intentional communities have a population close to 100, with many possibly exceeding this number.[62]While this may seem large, it is pretty small in comparison to the rest of society. From the small populations, it is apparent that people do not prefer this kind of living[citation needed].While many of these new small communities failed, some continue to grow, such as the religion-basedTwelve Tribes,which started in the United States in 1972. Since its inception, it has grown into many groups around the world. Similarly, a commune calledBrook Farmestablished itself in 1841. Founded by Charles Fourier's visions of Utopia, they attempted to recreate his idea of a central building in society called the Phalanx.[63]Unfortunately, this commune could not sustain itself and failed after only six years of operation. They wanted to stay open for longer, but they could not afford it. Their goal, however, was very similar to that of Utopia: to lead a more wholesome and simpler life than the atmosphere of pressure surrounding society at the time.[63]It is clear that despite ambition, it is difficult for communes to stay in operation for very long.

Science and technology

editThoughFrancis Bacon'sNew Atlantisis imbued with a scientific spirit, scientific and technological utopias tend to be based in the future, when it is believed that advancedscienceandtechnologywill allow utopianliving standards;for example, the absence ofdeathandsuffering;changes inhuman natureand thehuman condition.Technology has affected the way humans have lived to such an extent that normal functions, like sleep, eating or even reproduction, have been replaced by artificial means. Other examples include a society where humans have struck a balance with technology and it is merely used to enhance the human living condition (e.g.Star Trek). In place of the static perfection of a utopia,libertarian transhumanistsenvision an "extropia",an open, evolving society allowing individuals and voluntary groupings to form the institutions and social forms they prefer.

Mariah Utsawapresented a theoretical basis fortechnological utopianismand set out to develop a variety of technologies ranging from maps to designs for cars and houses which might lead to the development of such a utopia. In his bookDeep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World,philosopherNick Bostromexplores what to do in a "solved world", assuming that human civilization safely buildsmachine superintelligenceand manages to solve its political, coordination and fairness problems. He outlines some technologies considered physically possible at technological maturity, such ascognitive enhancement,reversal of aging,self-replicating spacecrafts,arbitrary sensory inputs (taste, sound...), or the precise control of motivation, mood, well-being and personality.[64]

One notable example of a technological andlibertarian socialistutopia is Scottish authorIain Banks'Culture.

Opposing thisoptimisticperspective are scenarios where advanced science and technology will, through deliberate misuse or accident, cause environmental damage or even humanity'sextinction.Critics, such asJacques EllulandTimothy Mitchelladvocateprecautionsagainst the premature embrace of new technologies. Both raise questions about changing responsibility and freedom brought bydivision of labour.Authors such asJohn ZerzanandDerrick Jensenconsider that modern technology is progressively depriving humans of their autonomy and advocate the collapse of the industrial civilization, in favor of small-scale organization, as a necessary path to avoid the threat of technology on human freedom andsustainability.

There are many examples of techno-dystopias portrayed in mainstream culture, such as the classicsBrave New WorldandNineteen Eighty-Four,often published as "1984", which have explored some of these topics.

Ecological

editEcological utopian society describes new ways in which society should relate to nature.Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Westonfrom 1975 by Ernest Callenbach was one of the first influential ecological utopian novels.[65]Richard Grove's bookGreen Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism 1600–1860from 1995 suggested the roots of ecologicalutopian thinking.[66]Grove's book sees early environmentalism as a result of the impact of utopian tropical islands on European data-driven scientists.[67]The works on ecological eutopia perceive a widening gap between the modern Western way of living that destroys nature[68]and a more traditional way of living before industrialization.[69]Ecological utopias may advocate a society that is more sustainable. According to the Dutch philosopherMarius de Geus,ecological utopias could be inspirational sources for movements involvinggreen politics.[70]

Feminism

editUtopias have been used to explore the ramifications of genders being either a societal construct or a biologically "hard-wired" imperative or some mix of the two.[71]Socialist and economic utopias have tended to take the "woman question" seriously and often to offer some form of equality between the sexes as part and parcel of their vision, whether this be by addressing misogyny, reorganizing society along separatist lines, creating a certain kind of androgynous equality that ignores gender or in some other manner. For example,Edward Bellamy'sLooking Backward(1887) responded, progressively for his day, to the contemporary women's suffrage and women's rights movements. Bellamy supported these movements by incorporating the equality of women and men into his utopian world's structure, albeit by consigning women to a separate sphere of light industrial activity (due to women's lesser physical strength) and making various exceptions for them in order to make room for (and to praise) motherhood. One of the earlier feminist utopias that imagines complete separatism isCharlotte Perkins Gilman'sHerland(1915).[citation needed]

Inscience fiction and technological speculation,gender can be challenged on the biological as well as the social level.Marge Piercy'sWoman on the Edge of Timeportrays equality between the genders and complete equality in sexuality (regardless of the gender of the lovers). Birth-giving, often felt as the divider that cannot be avoided in discussions of women's rights and roles, has been shifted onto elaborate biological machinery that functions to offer an enriched embryonic experience. When a child is born, it spends most of its time in the children's ward with peers. Three "mothers" per child are the norm and they are chosen in a gender neutral way (men as well as women may become "mothers" ) on the basis of their experience and ability. Technological advances also make possible the freeing of women from childbearing inShulamith Firestone'sThe Dialectic of Sex.The fictional aliens inMary Gentle'sGolden Witchbreedstart out as gender-neutral children and do not develop into men and women until puberty and gender has no bearing on social roles. In contrast,Doris Lessing'sThe Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five(1980) suggests that men's and women's values are inherent to the sexes and cannot be changed, making a compromise between them essential. InMy Own Utopia(1961) byElizabeth Mann Borghese,gender exists but is dependent upon age rather than sex – genderless children mature into women, some of whom eventually become men.[71]"William Marston'sWonder Womancomics of the 1940s featured Paradise Island, also known asThemyscira,a matriarchal all-female community of peace, loving submission, bondage and giant space kangaroos. "[72]

Utopiansingle-gender worldsor single-sex societies have long been one of the primary ways to explore implications of gender and gender-differences.[73]In speculative fiction, female-only worlds have been imagined to come about by the action of disease that wipes out men, along with the development of technological or mystical method that allow femaleparthenogenicreproduction.Charlotte Perkins Gilman's 1915 novel approaches this type of separate society. Many feminist utopias pondering separatism were written in the 1970s, as a response to theLesbian separatist movement;[73][74][75]examples includeJoanna Russ'sThe Female ManandSuzy McKee Charnas'sWalk to the End of the WorldandMotherlines.[75]Utopias imagined by male authors have often included equality between sexes, rather than separation, although as noted Bellamy's strategy includes a certain amount of "separate but equal".[76]The use of female-only worlds allows the exploration of female independence and freedom frompatriarchy.The societies may be lesbian, such asDaughters of a Coral DawnbyKatherine V. Forrestor not, and may not be sexual at all – a famous early sexless example beingHerland(1915) byCharlotte Perkins Gilman.[74]Charlene Ball writes inWomen's Studies Encyclopediathat use of speculative fiction to explore gender roles in future societies has been more common in the United States compared to Europe and elsewhere,[71]although such efforts asGerd Brantenberg'sEgalia's DaughtersandChrista Wolf's portrayal of the land of Colchis in herMedea: Voicesare certainly as influential and famous as any of the American feminist utopias.

Urban Design

editWalter Elias Disney's originalEPCOT (concept)(Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow),Paolo Soleri'sArcosanti,and Saudi PrinceMohammed bin Salman'sNeomare examples of Utopian city design.

Critical Utopia

editCritical utopia is a theory conceptualised by literary theoristTom Moylan.[77]In contrast with utopianism, critical utopia rejects utopia. The idea is highlyself-referentialand uses the idea of utopia to advance society while critiquing it simultaneously. A problem with utopianism is identified: it has limitations since the imagined utopia is significantly distant from current society. Utopia also fails to acknowledge the differences between people that result in differences in experience.[77]Moylan explains that "[critical utopias] ultimately refer to something other than a predictable alternative paradigm, for at their core they identify self-critical utopian discourse itself as a process that can tear apart the dominant ideological web. Here, then, critical utopian discourse becomes a seditious expression of social change and popular sovereignty carried on in a permanently open process of envisioning what is not yet."[78]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^Giroux, Henry A.(2003)."Utopian thinking under the sign of neoliberalism: Towards a critical pedagogy of educated hope"(PDF).Democracy & Nature.9(1).Routledge:91–105.doi:10.1080/1085566032000074968.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2019-12-05.Retrieved2018-03-11.

- ^Giroux, H. (2003). "Utopian thinking under the sign of neoliberalism: Towards a critical pedagogy of educated hope".Democracy & Nature.9(1): 91–105.doi:10.1080/1085566032000074968.

- ^Sargent, Lyman Tower (2010).Utopianism: A very short introduction.Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 21.doi:10.1093/actrade/9780199573400.003.0002.ISBN978-0-19-957340-0.

- ^"Definitions | Utopian Literature in English: An Annotated Bibliography From 1516 to the Present".openpublishing.psu.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 4 September 2022.Retrieved4 September2022.

- ^abSargent, Lyman Tower (2005). Rüsen, Jörn; Fehr, Michael; Reiger, Thomas W. (eds.). The Necessity of Utopian Thinking: A cross-national perspective.Thinking Utopia: Steps into Other Worlds(Report). New York: Berghahn Books. p. 11.ISBN978-1-57181-440-1.

- ^Lodder, C.; Kokkori, M; Mileeva, M. (2013).Utopian Reality: Reconstructing culture in revolutionary Russia and beyond.Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. pp. 1–9.ISBN978-90-04-26320-8.

- ^Uchronia: Uchronie (l'utopie dans l'histoire), esquisse historique apocryphe du développement de la civilisation européenne tel qu'il n'a pas été, tel qu'il aurait pu être,Uchronia.net,archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-11,retrieved2011-10-01,reprinted 1988,ISBN2-213-02058-2.

- ^Douglas, Christopher (2013). ""Something That Has Already Happened": Recapitulation and Religious Indifference in The Plot Against America ".MFS Modern Fiction Studies.59(4): 784–810.doi:10.1353/mfs.2013.0045.ISSN1080-658X.S2CID162310618.

- ^Fondanèche, Daniel; Chatelain, Danièle; Slusser, George (1988). "Dick, the Libertarian Prophet (Dick: une prophète libertaire)".Science Fiction Studies.15(2): 141–151.ISSN0091-7729.JSTOR4239877.

- ^Filozofický slovník 1977, s. 561

- ^PERNÝ, Lukáš: Utopians, Visionaries of the World of the Future (The History of Utopias and Utopianism), Martin: Matica slovenská, 2020, p. 16

- ^LEFEBVRE, Henri (2000 [1968]) Everyday Life in the Modern World. Translated by Sacha Rabinovitch. London: The Athlone Press, p.75.

- ^Emma Goldman, “Socialism Caught in the Political TrapArchived2024-05-25 at theWayback Machine,”in Red Emma Speaks: An Emma Goldman Reader, ed. Alix Kates Shulman, freely available at the Anarchist Library.

- ^Frederick Engels. Socialism: Utopian and Scientific.

- ^"Slavoj Žižek on Utopia".Archivedfrom the original on 2019-08-21.Retrieved2019-08-21.

- ^ŠIMEČKA, M. (1963): Sociálne utópie a utopisti, Bratislava: Vydavateľstvo Osveta.

- ^SŤAHEL, R. In: MICHALKOVÁ, R.: Symposion: Utópie. Bratislava: RTVS. 2017.

- ^More, Travis; Vinod, Rohith (1989)

- ^"Thomas More's Utopia".bl.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2017.Retrieved14 May2017.

- ^"Utopian Socialism".utopiaanddystopia.com.The Utopian Socialism Movement.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2017.Retrieved14 May2017.

- ^Dalley, Jan (30 December 2015)."Openings: Going back to Utopia".Financial Times.London.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-12-10.Retrieved27 August2018.

- ^Robert Paul Sutton,Communal Utopias and the American Experience: Religious Communities(2003) p. 38

- ^Teuvo Peltoniemi (1984)."Finnish Utopian Settlements in North America"(PDF).sosiomedia.fi. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2010-10-26.Retrieved2008-10-12.

- ^Sosis, Richard (2000)."Religion and Intragroup Cooperation: Preliminary Results of a Comparative Analysis of Utopian Communities"(PDF).Cross-Cultural Research.34(1).SAGE Publishing:70–87.doi:10.1177/106939710003400105.S2CID44050390.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on January 25, 2020.RetrievedJanuary 7,2020.

- ^Sosis, Richard; Bressler, Eric R. (2003). "Cooperation and Commune Longevity: A Test of the Costly Signaling Theory of Religion".Cross-Cultural Research.37(2).SAGE Publishing:211–239.CiteSeerX10.1.1.500.5715.doi:10.1177/1069397103037002003.S2CID7908906.

- ^Haidt, Jonathan(2012).The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion.New York:Vintage Books.pp. 298–299.ISBN978-0307455772.

- ^Nesse, Randolph(2019).Good Reasons for Bad Feelings: Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry.Dutton.pp. 172–176.ISBN978-1101985663.

- ^West-Eberhard, Mary Jane (1975). "The Evolution of Social Behavior by Kin Selection".The Quarterly Review of Biology.50(1).University of Chicago Press:1–33.doi:10.1086/408298.JSTOR2821184.S2CID14459515.

- ^West-Eberhard, Mary Jane (1979). "Sexual Selection, Social Competition, and Evolution".Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.123(4).American Philosophical Society:222–34.JSTOR986582.

- ^Nesse, Randolph M.(2007). "Runaway social selection for displays of partner value and altruism".Biological Theory.2(2).Springer Science+Business Media:143–55.CiteSeerX10.1.1.409.3359.doi:10.1162/biot.2007.2.2.143.S2CID195097363.

- ^Nesse, Randolph M.(2009). "10. Social Selection and the Origins of Culture". InSchaller, Mark;Heine, Steven J.;Norenzayan, Ara; Yamagishi, Toshio; Kameda, Tatsuya (eds.).Evolution, Culture, and the Human Mind.Philadelphia:Taylor & Francis.pp. 137–50.ISBN978-0805859119.

- ^Rev 21:1;4

- ^65:17

- ^Joel B. Green;Jacqueline Lapsley; Rebekah Miles; Allen Verhey, eds. (2011).Dictionary of Scripture and Ethics.Ada Township, Michigan:Baker Books.p.190.ISBN978-1-4412-3998-3.

This goodness theme is advanced most definitively through the promise of a renewal of all creation, a hope present in OT prophetic literature (Isa. 65:17–25) but portrayed most strikingly through Revelation's vision of a "new heaven and a new earth" (Rev. 21:1). There the divine king of creation promises to renew all of reality: "See, I am making all things new" (Rev. 21:5).

- ^Steve Moyise; Maarten J.J. Menken, eds. (2005).Isaiah in the New Testament. The New Testament and the Scriptures of Israel.London:Bloomsbury Publishing.p.201.ISBN978-0-567-61166-6.

By alluding to the new Creation prophecy of Isaiah John emphasizes the qualitatively new state of affairs that will exist at God's new creative act. In addition to the passing of the former heaven and earth, John also asserts that the sea was no more in 21:1c.

- ^"The Book of the Secrets of Enoch, Chapters 1-68".The Reluctant Messenger.Archivedfrom the original on 26 October 2022.Retrieved14 May2017.

- ^M.I.Finley, World of Odysseus, 1954, 100.

- ^Homer Odyssey 6:251-7:155

- ^Rev 21:1

- ^Haag, Herbert(1969).Is original sin in Scripture?.New York:Sheed and Ward.ISBN9780836202502.Germanor. ed.:1966.

- ^Genesis 2:25

- ^(in German)Haag, Herbert (1966). pp.1, 49ff.

- ^Cobham Brewer E.Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable,Odhams, London, 1932

- ^Tian, Xiaofei (2010). "From the Eastern Jin through the Early Tang (317–649)".The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 221.ISBN978-0-521-85558-7.

- ^Berkowitz, Alan J. (2000).Patterns of Disengagement: the Practice and Portrayal of Reclusion in Early Medieval China.Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 225.ISBN978-0-8047-3603-9.

- ^abLongxi, Zhang (2005).Allegoresis: Reading Canonical Literature East and West.Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 182.ISBN978-0-8014-4369-5.

- ^abLongxi, Zhang (2005).Allegoresis: Reading Canonical Literature East and West.Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 182–183.ISBN978-0-8014-4369-5.

- ^abcdLongxi, Zhang (2005).Allegoresis: Reading Canonical Literature East and West.Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 183.ISBN978-0-8014-4369-5.

- ^Gu, Ming Dong (2006).Chinese Theories of Fiction: A Non-Western Narrative System.Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 59.ISBN978-0-7914-6815-9.

- ^Patry, Denise; Strahan, Donna; Becker, Lawrence (2010).Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 58.ISBN9781588393999.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-07-15.Retrieved2023-03-20.

- ^Maddegama, Udaya (1993).Sermon of the Chronicle-to-be.Motilal Banarsidass.pp. 32–33.ISBN9788120811331.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-06-15.Retrieved2023-03-20.

- ^Heller, Nathan (2018-07-02)."Who Really Stands to Win from Universal Basic Income?".The New Yorker.ISSN0028-792X.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-08-25.Retrieved2019-08-25.

- ^"Are Danes Really That Happy? The Myth of the Scandinavian Utopia".NPR.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-08-25.Retrieved2019-08-25.

- ^

Woollacott, Angela(2015). "Systematic Colonization: From South Australia to Australind".Settler Society in the Australian Colonies: Self-Government and Imperial Culture.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 39.ISBN9780191017735.Retrieved24 June2020.

In Wakefield's utopia, land policy would limit the expansion of the frontier and regulate class relationships.

- ^"the Thaw – Soviet cultural history".Archivedfrom the original on 11 September 2017.Retrieved14 May2017.

- ^Fries, Sylvia,The Urban Idea in Colonial America,Chapters 3 and 5

- ^Home, Robert,Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities,9

- ^Wilson, Thomas,The Oglethorpe Plan,Chapters 1 and 2

- ^"America and the Utopian Dream – Utopian Communities".brbl-archive.library.yale.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 8 May 2017.Retrieved14 May2017.

- ^"For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements and Communalism in America, 2nd Edition".secure.pmpress.org.Archived fromthe originalon 2017-02-28.Retrieved2017-04-26.

- ^Curl, John(2009). "Communalism in the 20th Century".For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America(2 ed.). Oakland, California: PM Press (published 2012). pp. 312–333.ISBN9781604867329.Retrieved24 June2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^Sager, Tore (August 17, 2017)."Planning by intentional communities: An understudied form of activist planning".Planning Theory.17(4): 449–471.doi:10.1177/1473095217723381.hdl:11250/2598634.ISSN1473-0952.Archivedfrom the original on November 9, 2023.RetrievedApril 13,2024.

- ^ab"Brook Farm | Transcendentalist Utopia, West Roxbury, MA | Britannica".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-05-07.Retrieved2024-04-13.

- ^Bostrom, Nick (March 27, 2024).Deep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World.ISBN978-1646871643.

- ^Archived atGhostarchiveand theWayback Machine:Callenbach, Ernest; Heddle, James.""Ecotopia Then & Now," an interview with Ernest Callenbach ".Retrieved2013-04-06– viaYouTube.

- ^Grove, Richard (1995)."Green imperialism: colonial expansion, tropical island Edens, and the origins of environmentalism, 1600-1860".Cambridge University Press.Archivedfrom the original on 25 May 2024.Retrieved14 August2022.

- ^Mollins, Julie (22 February 2021)."Selective memories: The historical roots of environmentalism".CIFOR Forests News.Archivedfrom the original on 16 August 2022.Retrieved16 August2022.

- ^Kirk, Andrew G. (2007).Counterculture Green: the Whole Earth Catalog and American environmentalism.University Press of Kansas. p. 86.ISBN978-0-7006-1545-2.

- ^For examples and explanations, see:Marshall, Alan (2016).Ecotopia 2121: A Vision of Our Future Green Utopia.New York: Arcade Publishers.ISBN978-1-62872-614-5.And Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew, and Bellamy, Brent Ryan (2019).An Ecotopian Lexicon.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.ISBN978-151790-589-7

- ^de Geus, Marius (1996).Ecologische utopieën – Ecotopia's en het milieudebat.Uitgeverij Jan van Arkel.

- ^abcTierney, Helen (1999).Women's Studies Encyclopedia.Greenwood Publishing Group. p.1442.ISBN978-0-313-31073-7.

- ^Noah Berlatsky, "Imagine There's No Gender: The Long History of Feminist Utopian Literature,"The Atlantic,April 15, 2013.https://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/2013/04/imagine-theres-no-gender-the-long-history-of-feminist-utopian-literature/274993/Archived2013-08-27 atarchive.today

- ^abAttebery, p. 13.

- ^abGaétan Brulotte& John Phillips,Encyclopedia of Erotic Literature,"Science Fiction and Fantasy", CRC Press, 2006, p. 1189,ISBN1-57958-441-1

- ^abMartha A. Bartter,The Utopian Fantastic,"Momutes",Robin Anne Reid,p. 101ISBN0-313-31635-X

- ^Martha A. Bartter,The Utopian Fantastic,"Momutes",Robin Anne Reid,p. 102[ISBN missing]

- ^abMoylan, Tom (1986).Demand the Impossible.Methuen, Inc.ISBN0 416 00012 6.

- ^Gardiner, Michael (1993). "Bakhtin's Carnival: Utopia as Critique".Bakhtin: Carnival and Other Subjects.3–4(2-1/2): 20–47.ISSN0923-411X.

- Bundled references

References

edit- Living in the Future: Utopianism and the Long Civil Rights Movement(2022) by Victoria Wolcott

- Utopia: Music album(2023), by Travis Scott.

- Utopia: The History of an Idea(2020), by Gregory Claeys. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Two Kinds of Utopia,(1912) byVladimir Lenin.www

.marxists .org /archive /lenin /works /1912 /oct /00 .htm - Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science(1870?) byFriedrich Engels.

- Ideology and Utopia: an Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge(1936), byKarl Mannheim,translated by Louis Wirth and Edward Shils. New York, Harcourt, Brace. See original,Ideologie Und Utopie,Bonn: Cohen.

- History and Utopia(1960), byEmil Cioran.

- Utopian Thought in the Western World(1979), byFrank E. Manuel& Fritzie Manuel. Oxford: Blackwell.ISBN0-674-93185-8

- California's Utopian Colonies(1983), by Robert V. Hine. University of California Press.ISBN0-520-04885-7

- The Principle of Hope(1986), byErnst Bloch.See original, 1937–41,Das Prinzip Hoffnung

- Demand the Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination(1986) byTom Moylan.London: Methuen, 1986.

- Utopia and Anti-utopia in Modern Times(1987), by Krishnan Kumar. Oxford: Blackwell.ISBN0-631-16714-5

- The Concept of Utopia(1990), byRuth Levitas.London: Allan.

- Utopianism(1991), by Krishnan Kumar. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.ISBN0-335-15361-5

- La storia delle utopie(1996), by Massimo Baldini. Roma: Armando.ISBN9788871444772

- The Utopia Reader(1999), edited byGregory ClaeysandLyman Tower Sargent.New York: New York University Press.

- Spirit of Utopia(2000), byErnst Bloch.See original,Geist Der Utopie,1923.

- Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions(2005) byFredric Jameson.London: Verso.

- Utopianism: A Very Short Introduction(2010), byLyman Tower Sargent.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Defined by a Hollow: Essays on Utopia, Science Fiction and Political Epistemology(2010) byDarko Suvin.Frankfurt am Main, Oxford and Bern: Peter Lang.

- Existential Utopia: New Perspectives on Utopian Thought(2011), edited by Patricia Vieira andMichael Marder.London & New York: Continuum.ISBN1-4411-6921-0

- "Galt's Gulch: Ayn Rand's Utopian Delusion" (2012), by Alan Clardy.Utopian Studies23, 238–262.ISSN1045-991X

- The Nationality of Utopia: H. G. Wells, England, and the World State(2020), by Maxim Shadurski. New York and London: Routledge.ISBN978-03-67330-49-1

- Utopia as a World Model: The Boundaries and Borderlands of a Literary Phenomenon(2016), by Maxim Shadurski. Siedlce: IKR[i]BL.ISBN978-83-64884-57-3.

- An Ecotopian Lexicon(2019), edited by Matthew Schneider-Mayerson and Brent Ryan Bellamy. University of Minnesota Press.ISBN978-1517905897.

External links

edit- .Catholic Encyclopedia.1913.

- Utopia – The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001

- Intentional Communities Directory

- History of 15 Finnishutopian settlements in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Australia and Europe.

- Towards Another Utopia of The CityInstitute of Urban Design, Bremen, Germany

- Ecotopia 2121: A Vision of Our Future Green Utopia – in 100 Cities.

- UtopiasArchived2010-07-08 at theWayback Machine– a learning resource from theBritish Library

- Utopia of the GOODAn essay on Utopias and their nature.

- Review of Ehud Ben ZVI, Ed. (2006). Utopia and Dystopia in Prophetic Literature. Helsinki: The Finnish Exegetical Society.A collection of articles on the issue of utopia and dystopia.

- The story of UtopiasMumford, Lewis

- [1]North America

- [2]Europe

- Utopian Studiesacademic journal

- Matthew Pethers."Utopia".Words of the World.Brady Haran(University of Nottingham). Archived fromthe originalon 2021-09-20.Retrieved2016-01-03.