Whiplashis a 2014 Americanpsychological dramafilm written and directed byDamien Chazelle,starringMiles Teller,J. K. Simmons,Paul Reiser,andMelissa Benoist.It focuses on an ambitious music student and aspiring jazz drummer (Teller), who is pushed to his limit by his abusive instructor (Simmons) at the fictional Shaffer Conservatory in New York City.

| Whiplash | |

|---|---|

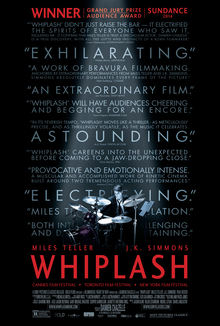

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Damien Chazelle |

| Written by | Damien Chazelle |

| Based on | Whiplash by Damien Chazelle |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Sharone Meir |

| Edited by | Tom Cross |

| Music by | Justin Hurwitz |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 106 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.3 million[2] |

| Box office | $49 million[2] |

The film was produced byBold Films,Blumhouse Productions,and Right of Way Films.Sony Picturesacquired distribution rights for most of the world, releasing the film underSony Pictures Classicsin North America, Germany, and Australia, andStage 6 Filmsin select international territories.[3][4]

Chazelle completed the script in 2013, drawing upon his experiences in a "very competitive" jazz band in high school. Soon after, Right of Way and Blumhouse helped Chazelle turn fifteen pages of the script into an eighteen-minute short film, also titledWhiplash.The short film received acclaim after debuting at the2013 Sundance Film Festival,which attracted investors to produce the complete version of the script. Filming took place in September 2013 throughout Los Angeles over the course of twenty days. The film explores concepts of perfectionism, dedication, and success and deconstructs the concept of ambition.

Whiplashpremiered in competition at the2014 Sundance Film Festivalon January 16, as the festival's opening film; it won the Audience Award and Grand Jury Prize for drama.[5]The film opened in limited release domestically in the United States and Canada on October 10, 2014, gradually expanding to over 500 screens and finally closing on March 26, 2015. The film received acclaim for its screenplay, direction, editing, sound mixing, and performances. It grossed $49 million on a $3.3 million budget, making it Chazelle's highest-grossing feature untilLa La Land(2016). The film receivedmultiple accolades,winningAcademy AwardsforBest Film EditingandBest Sound Mixing,and was nominated forBest PictureandBest Adapted Screenplay.Simmons's performance won theAcademy,BAFTA,Critics' Choice,Golden Globe,andScreen Actors Guildawards for Best Supporting Actor. It has since been assessed as one of the best films of the 2010s, the 21st century andof all time.[6][7][8][9][10]

Plot

editJazz drummerAndrew Neiman attends the prestigious Shaffer Conservatory inNew York City,hoping one day to leave a legacy like that of his childhood idolBuddy Rich.Terence Fletcher, the conductor of the Shaffer Conservatory Studio Band, recruits him to play in the Studio ensemble as an alternate for core drummer Carl Tanner. Andrew quickly discovers that Fletcher, although encouraging at first, is relentlessly strict and both verbally and physically abusive towards his students. When Andrew fails to keep tempo during his first ensemble rehearsal ofHank Levy's "Whiplash",Fletcher throws a chair at him, slaps his face, and berates him.

Determined to impress Fletcher, Andrew excessively practices, oftentimes until his hands blister and bleed. After their first set at a jazz competition, Andrew misplaces Tanner's sheet music. Tanner cannot play without the sheets, so Andrew replaces him to successfully perform "Whiplash" from memory. Fletcher promotes him to core drummer. However, Andrew is taken aback when Fletcher abruptly reassigns the position to Ryan Connolly, a drummer from a lower-level ensemble within Shaffer. Because of his single-mindedness toward music, Andrew clashes with his family. He breaks up with his girlfriend, Nicole, to focus on his ambitions. One day, Fletcher begins rehearsal by mournfully announcing that Sean Casey, a promising former member of the Studio Band, died in a car accident. Fletcher then pushes the three drummers to play at a faster tempo on "Caravan",keeping the band for a grueling five-hour practice before Andrew earns back the core position.

On the way to the next competition, Andrew's bus gets a flat tire. He rents a car but arrives late and forgets his sticks at the rental office. After Fletcher reluctantly agrees to wait, Andrew races back and retrieves them, but his car is hit by a truck on the way back. Heavily injured, he crawls from the wreckage and runs to the theater, arriving bloodied and weak just as the ensemble enters the stage. He struggles to play, and Fletcher halts the performance to dismiss him from the band. Enraged, Andrew attacks Fletcher onstage but is pulled away by security and expelled from Shaffer. At his father's request, Andrew meets a lawyer representing the parents of the late Sean Casey, who was not in a car accident, but in realityhanged himselfafter suffering depression and anxiety allegedly inflicted by Fletcher's abuse. Casey's parents want Fletcher held accountable, and Andrew reluctantly agrees to testify anonymously, leading Shaffer to terminate Fletcher.

Andrew abandons drumming, but months later encounters Fletcher playing piano at a jazz club. Over a drink, Fletcher admits his teaching methods were harsh but insists they were necessary to motivate his students to become successful. Citing an incident whenJo Jonesthrew a cymbal atCharlie Parkeras an example, Fletcher says the worst words that could be said to a student are "Good job." He invites Andrew to perform with his band at theJVC Jazz Festival,playing the same songs from the Studio Band; Andrew hesitantly accepts. Andrew calls Nicole to invite her to the performance, but learns she is in a new relationship.

At JVC, Fletcher confronts Andrew and reveals he knows Andrew testified against him. As revenge, Fletcher leads the band into a song Andrew does not know and was not provided sheet music for. After a disastrous performance, Andrew walks offstage, humiliated. His father embraces him backstage, but Andrew returns to the stage, reclaims the drum kit, and cuts off Fletcher's introduction to the next piece by cueing the band into "Caravan". Initially angered, Fletcher resumes conducting. As the piece finishes, Andrew continues into an unexpected extended solo. Impressed, Fletcher assists him and nods in approval before cueing the finale.

Cast

edit- Miles Telleras Andrew Neiman, an ambitious young jazz drummer at Shaffer Conservatory

- J. K. Simmonsas Terence Fletcher, a ruthless jazz instructor at Shaffer

- Paul Reiseras Jim Neiman, Andrew's father, a writer turned high school teacher

- Melissa Benoistas Nicole, a movie theater employee who briefly dates Andrew

- Austin Stowellas Ryan Connolly, another drummer in Fletcher's band

- Nate Lang as Carl Tanner, another drummer in Fletcher's band

- Chris Mulkeyas Uncle Frank Neiman, Andrew's uncle

- Damon Guptonas Mr. Kramer, Andrew's first instructor before being recruited by Fletcher

Production

editDevelopment

editWhile attendingPrinceton High School,writer-directorDamien Chazellewas in the "very competitive" Studio Band and drew on the dread he felt in those years.[11]He based the conductor, Terence Fletcher, on his former band instructor (who died in 2003) but "pushed it further", adding elements ofBuddy Richand other band leaders known for their harsh treatment.[11]Chazelle wrote the film "initially in frustration" while trying to get his musicalLa La Landoff the ground.[12]

Right of Way Films and Blumhouse Productions helped Chazelle turn fifteen pages of his original screenplay into ashort filmstarringJohnny Simmonsas Neiman andJ. K. Simmons(no relation)[13]as Fletcher.[14]The eighteen-minute short film received acclaim after debuting at the2013 Sundance Film Festival,winning the short film Jury Award for fiction,[15]which attracted investors to produce the complete version of the script.[16]The feature-length film was financed for $3.3 million by Bold Films.[3]

In August 2013,Miles Tellersigned on to star in the role originated by Johnny Simmons; J. K. Simmons remained attached to his original role.[17]Early on, Chazelle gave J. K. Simmons direction that "I want you to take it past what you think the normal limit would be," telling him: "I don't want to see a human being on-screen any more. I want to see a monster, a gargoyle, an animal." Many of the band members were real musicians or music students, and Chazelle tried to capture their expressions of fear and anxiety when Simmons pressed them. Chazelle said that, in between takes, Simmons was "as sweet as can be", which he credits for keeping "the shoot from being nightmarish".[11]

Filming

editPrincipal photography began in September 2013, with filming taking place throughout Los Angeles, including the Hotel Barclay,Palace Theater,and theOrpheum Theatre.[18][19]The film was shot in nineteen days, with a schedule of fourteen hours of filming per day.[20]Chazelle was involved in a serious car accident in the third week of filming and was hospitalized with possible concussion, but he returned to set the following day to wrap the shoot on time.[20]

Having taught himself to play drums at age fifteen, Teller performed much of the drumming seen in the film. Supporting actor and jazz drummer Nate Lang, who plays Teller's rival Carl in the film, trained Teller in the specifics of jazz drumming; this included changing hisgripfrom "matched" to "traditional".[21][22]For certain scenes, professional drummerKyle Craneserved as Teller's drum double.[23][24]

Music

editThe soundtrack album was released on October 7, 2014, viaVarèse Sarabandelabel.[25]The soundtrack consists of 24 tracks divided in three different parts: original jazz pieces written for the film, original underscore parts written for the film, and classic jazz standards written byStan Getz,Duke Ellington,and other musicians. The actual drummer wasBernie Dresel.[26]

On March 27, 2020, an expanded deluxe edition was released on double CD and 2-LP gatefold sleeve vinyl with new cover art, and featured original music by Justin Hurwitz, plus bonus track and remixes by Timo Garcia, Opiuo,Murray A. Lightburnand more.[27]

Reception

editBox office

editIn North America, the film opened in alimited releaseon October 10, 2014, in 6 theaters, grossing $135,388 ($22,565 per theater) and finishing 34th at the box office.[2]It expanded to 88 locations, then 419 locations.[28]After three months on release it had earned $7 million, and finally expanded nationwide to 1000 locations to capitalize on receiving five Academy Awards nominations.[29]Whiplashgrossed $13.1 million in the U.S. and Canada and $35.9 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $49 million against a budget of $3.3 million.[2]

Critical response

editOn the review aggregation websiteRotten Tomatoes,the film scored 94% based on 307 reviews, with an average rating of 8.6/10. The site's critical consensus states, "Intense, inspiring, and well-acted,Whiplashis a brilliant sophomore effort from director Damien Chazelle and a riveting vehicle for stars J. K. Simmons and Miles Teller. "[30]OnMetacriticthe film has a score of 89 out of 100, based on reviews from 49 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[31]Simmons received wide praise for his performance and won the2015Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[32][33]

Peter Debruge, in his review forVariety,said that the film "demolishes the cliches of the musical-prodigy genre, investing the traditionally polite stages and rehearsal studios of a topnotch conservatory with all the psychological intensity of a battlefield or sports arena."[34]Todd McCarthyofThe Hollywood Reporterpraised the performances of Teller and Simmons, writing: "Teller, who greatly impressed in last year's Sundance entryThe Spectacular Now,does so again in a performance that is more often simmering than volatile... Simmons has the great good fortune for a character actor to have here found a co-lead part he can really run with, which is what he excitingly does with a man who is profane, way out of bounds and, like many a good villain, utterly compelling. "[35]Whiplashalso won the 87thAcademy Award for Best Sound Mixingand the 87thAcademy Award for Best Film Editing.[36]

Amber Wilkinson ofThe Daily Telegraphpraised the direction and editing, writing: "Chazelle's film has a sharp and gripping rhythm, with shots beautifully edited byTom Cross... often cutting to the crash of Andrew's drums. "[37]James Rocchi ofIndiewiregave a positive review and said, "Whiplashis... full of bravado and swagger, uncompromising where it needs to be, informed by great performances and patient with both its characters and the things that matter to them. "[38]Henry Barnes ofThe Guardiangave the film a positive review, calling it a rare film "about music that professes its love for the music and its characters equally."[36]

Forrest Wickman ofSlatesaid the film distorted jazz history and promoted a misleading idea of genius, adding that "In all likelihood, Fletcher isn't making a Charlie Parker. He's making the kind of musician that would throw a cymbal at him."[39]InThe New Yorker,Richard Brodysaid, "Whiplashhonors neither jazz nor cinema. "[40]

Top ten lists

editThe film appeared on many critics' end-of-year lists. Metacritic collected lists published by major film critics and publications and in their analysis, recorded thatWhiplashappeared on 57 lists and in 1st place on 5 of those lists. Overall the film was ranked in 5th place for the year byMetacritic.[41]

- 1st – William Bibbiani,CraveOnline

- 1st – Chris Nashawaty,Entertainment Weekly[42]

- 1st – Erik Davis,Movies.com

- 2nd – A. A. Dowd,The A.V. Club[43]

- 2nd – Scott Feinberg,The Hollywood Reporter

- 2nd – Mara Reinstein,Us Weekly

- 3rd – Tasha Robinson,The Dissolve

- 3rd – Amy Taubin,Artforum

- 3rd – Steve Persall,Tampa Bay Times

- 3rd – Matt Singer,ScreenCrush

- 3rd – Rob Hunter,Film School Rejects

- 4th –Ignatiy Vishnevetsky,The A.V. Club[43]

- 4th –Kyle Smith,New York Post

- 4th – Peter Hartlaub,San Francisco Chronicle

- 4th – Brian Miller,Seattle Weekly

- 4th –Michael Phillips,Chicago Tribune

- 4th –David Edelstein,Vulture

- 5th –Ty Burr,The Boston Globe

- 5th – Genevieve Koski,The Dissolve

- 5th –James Berardinelli,Reelviews

- 5th –David Ansen,The Village Voice[44]

- 5th – Betsy Sharkey,Los Angeles Times(tied withFoxcatcher)

- 6th –Peter Travers,Rolling Stone

- 6th –Richard Roeper,Chicago Sun-Times

- 6th – Joe Neumaier,New York Daily News

- 7th – Jesse Hassenger,The A.V. Club[43]

- 7th –Rex Reed,New York Observer

- 7th – Noel Murray,The Dissolve

- 7th – Jocelyn Noveck,Associated Press

- 7th –Wesley Morris,Grantland

- 7th – Alison Willmore,BuzzFeed

- 8th – Keith Phipps,The Dissolve

- 8th – Mike Scott,The Times-Picayune

- 8th – Rafer Guzman,Newsday

- 8th – Seth Malvín Romero,A.V. Wire

- 8th – Ben Kenigsberg,The A.V. Club[43]

- 8th – Barbara Vancheri,Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

- 8th – Kristopher Tapley,Hitfix

- 8th – Matthew Jacobs and Christopher Rosen,Huffington Post

- 9th –Nathan Rabin,The Dissolve

- 10th – Clayton Davis, Awards Circuit

- 10th –Owen Gleiberman,BBC

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Claudia Puig,USA Today

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Stephen Whitty,The Star-Ledger

Accolades

editThe film received the top audience and grand jury awards in the U.S. dramatic competition at the2014 Sundance Film Festival;[45]Chazelle's short film of the same name took home the jury award in the U.S. fiction category one year prior.[15]The film also took the grand prize and the audience award for its favorite film at the40th Deauville American Film Festival.[46]

Whiplashwas originally planned to compete for theAcademy Award for Best Original Screenplay,but on January 6, 2015, theAcademy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences(AMPAS) announced that the film would instead be competing in theAdapted Screenplaycategory[47]to the surprise of many including Chazelle,[48]due to the short film premiering at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival (one year before the feature film's release), even though the feature film's script was written first and the short was made to attract investors into producing the feature-length film.[14]Although theWriters Guild of Americacategorized the screenplay as original, AMPAS classed it as an adaptation of the 2013 short version.[48]

At the87th Academy Awards,J. K. Simmonsreceived theAcademy Award for Best Supporting Actorfor his performance,Tom Crosswon theAcademy Award for Best Film EditingandCraig Mann,Ben WilkinsandThomas Curleywon theAcademy Award for Best Sound Mixing.In December 2015, the score received aGrammynomination, and the film was nominated for theNME Awardfor Best Film.[49]

In 2020, it ranked 13 onEmpire's list of "The 100 Greatest Movies Of The 21st Century."[50]In 2024, it topped the list of the Sundance Film Festival's Top 10 Films of All Time as the result of a survey conducted with 500 filmmakers and critics in honor of the festival's 40th anniversary.[51][52]

References

edit- ^"Whiplash".British Board of Film Classification.August 5, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on November 13, 2014.RetrievedNovember 12,2014.

- ^abcd"Whiplash (2014)".Box Office Mojo.Archivedfrom the original on October 9, 2015.RetrievedNovember 9,2015.

- ^abHorn, John (January 16, 2014)."Sundance 2014: Sony grabs international rights to 'Whiplash'".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on January 18, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^"Sundance: Sony Pictures Worldwide Acquisitions Nabs International Rights To Fest Opener 'Whiplash'".Deadline Hollywood.January 16, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 29,2023.

- ^Cohen, Sandy (January 17, 2014)."Sundance Film Festival 2014 opens with the premiere of 'Whiplash,' Damien Chazelle's tale of a brutal drumming instructor and his protege".The Oregonian.Associated Press.Archivedfrom the original on July 20, 2018.RetrievedJanuary 18,2014.

- ^"100 Greatest Movies of All Time".

- ^"The 10 Best Music Films of All Time (According to IMDb)".Screen Rant.February 8, 2020.

- ^Shoard, Catherine (December 9, 2014)."The 10 best films of 2014: No 4 – Whiplash".The Guardian.

- ^"The 100 Greatest Movies Of The 21st Century".Empire.March 18, 2020.Archivedfrom the original on August 17, 2021.RetrievedAugust 18,2023.

- ^Bergeson, Samantha (January 16, 2024)."'Whiplash' Named Top Sundance Film of All Time in Festival Poll of Over 500 Filmmakers and Critics ".IndieWire.RetrievedJanuary 26,2024.

- ^abcDowd, A.A (October 15, 2014)."Whiplash maestro Damien Chazelle on drumming, directing, and J. K. Simmons".The A.V. Club.Archivedfrom the original on January 3, 2015.RetrievedDecember 30,2014.

- ^Hammond, Pete (August 30, 2016)."Damien Chazelle'sLa La Land,An Ode To Musicals, Romance & L.A., Ready To Launch Venice And Oscar Season ".Deadline Hollywood.Archivedfrom the original on June 12, 2018.RetrievedSeptember 20,2016.

- ^Dowd, A. A. (September 21, 2016)."Two takes on Whiplash show that J.K. Simmons is scary in small doses, too".The A.V. Club.Archivedfrom the original on June 27, 2018.RetrievedJune 27,2018.

- ^abBahr, Lindsey (May 14, 2013)."'Whiplash': Sundance-winning short of becoming full-length feature ".Entertainment Weekly.CNN. Archived fromthe originalon February 26, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^ab"2013 Sundance Film Festival Announces Jury Awards in Short Filmmaking".www.sundance.org.January 23, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on January 24, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 21,2019.

- ^Fleming, Mike Jr. (May 14, 2013)."Cannes: Bold, Blumhouse, Right Of Way Strike Up Band For Feature Version Of Sundance ShortWhiplash".Deadline Hollywood.Penske Media Corporation.Archivedfrom the original on February 23, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^Fleming, Mike Jr. (August 5, 2013)."The Spectacular Now's Miles Teller GetsWhiplash".Deadline Hollywood.Penske Media Corporation.Archivedfrom the original on February 15, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^McNary, Dave (September 19, 2013)."Jake Gyllenhaal'sNightcrawlerGets California Incentive (Exclusive) ".Variety.Penske Media Corporation.Archivedfrom the original on November 1, 2013.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^"Tuesday, Sept. 24 Filming Locations for The Heirs, Undrafted, Dumb & Dumber To, Focus, Shelter, & more!".On Location Vacations. September 24, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on January 9, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^ab"Making of 'Whiplash': How a 20-Something Shot His Harrowing Script in Just 19 Days".The Hollywood Reporter.December 9, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on May 22, 2020.RetrievedMarch 4,2015.

- ^"Inside the Making of Oscar-NominatedWhiplash".ABC News.February 13, 2015.

- ^Tucker, Reed (October 4, 2014)."How Miles Teller learned to fake drum like a pro inWhiplash".New York Post.

- ^"Kyle Crane: Bigger Achievements".tapeop.com.RetrievedFebruary 16,2023.

- ^Morgenstern, Michael,Keeping Time: Kyle Crane on the Drums(Documentary, Short, Drama),retrievedFebruary 16,2023

- ^"WhiplashSoundtrack Details ".filmmusicreporter.com.Archivedfrom the original on May 23, 2017.RetrievedApril 10,2017.

- ^Van de Sande, Kris (February 5, 2016)."Talking animals with Zootopia's Creative Minds".Endor Express.Archivedfrom the original on February 26, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 26,2020.

- ^Micucci, Matt (February 20, 2020)."Listen to a Bonus Track from New Expanded" Whiplash "Soundtrack Album".JAZZIZ Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on June 22, 2020.RetrievedJune 19,2020.

- ^Ray Subers (November 16, 2014)."Weekend Report: 'Dumb' Sequel Takes First Ahead of 'Big Hero 6,' 'Interstellar'".Box Office Mojo.

- ^Ray Subers (January 22, 2015)."Forecast: Bombs Away for 'Mortdecai,' 'Strange Magic'".Box Office Mojo.

- ^"Whiplash (2014)".Rotten Tomatoes.Fandango Media.Archivedfrom the original on October 13, 2023.RetrievedOctober 13,2023.

- ^"Whiplash".Metacritic.CBS Interactive.Archivedfrom the original on October 13, 2023.RetrievedOctober 13,2023.

- ^Smith, Nigel M (October 15, 2014)."J. K. Simmons on HisWhiplashOscar Buzz and Abusing Miles Teller ".indieWire.Archivedfrom the original on October 18, 2014.RetrievedOctober 15,2014.

- ^Riley, Jenelle (September 3, 2014)."J. K. Simmons on Playing a 'Real' Villain inWhiplash".Variety.Archivedfrom the original on September 5, 2014.RetrievedSeptember 3,2014.

- ^"Sundance Film Review:Whiplash".Variety.January 17, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on January 20, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^"Whiplash: Sundance Review".The Hollywood Reporter.January 17, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on January 19, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^ab"Whiplash: Sundance 2014 – first look review".The Guardian.January 17, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on January 19, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^"Sundance 2014: Whiplash, review".The Telegraph.January 18, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on January 19, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^"Sundance Review:WhiplashStarring Miles Teller Leads With The Different Beat Of A Very Different Drum ".indieWire. Archived fromthe originalon February 19, 2015.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^Wickman, Forrest (October 11, 2014)."WhatWhiplashGets Wrong About Genius, Work, and the Charlie Parker Myth ".Slate.Archivedfrom the original on October 13, 2014.RetrievedOctober 13,2014.

- ^Brody, Richard(October 13, 2014)."Getting Jazz Right in the Movies".The New Yorker.Archivedfrom the original on April 20, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 5,2015.

- ^Dietz, Jason (December 6, 2014)."Best of 2014: Film Critic Top Ten Lists".Metacritic.RetrievedJune 6,2021.

- ^Nashawaty, Chris (December 4, 2014)."10 Best/5 Worst Movies of 2014".Entertainment Weekly.Archived fromthe originalon March 28, 2021.RetrievedMarch 28,2021.

- ^abcd"The best of film 2014: The ballots".The A.V. Club.December 18, 2014.

- ^"The 2014 Village Voice Film Critics' Poll".Archived fromthe originalon December 10, 2015.RetrievedAugust 26,2020.

- ^Zeitchik, Steven; Olsen, Mark (January 25, 2014)."Sundance 2014 winners: 'Whiplash' wins big".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on January 26, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 27,2014.

- ^Richford, Rhonda (September 13, 2014)."'Whiplash' Takes Top Prize in Deauville ".The Hollywood Reporter.Archivedfrom the original on September 14, 2014.RetrievedSeptember 13,2014.

- ^Tapley, Kristopher (January 6, 2015)."Oscar surprise: 'Whiplash' deemed an adapted screenplay by Academy".HitFix.Archivedfrom the original on January 6, 2015.RetrievedJanuary 6,2015.

- ^abHammond, Peter (January 6, 2015)."Academy & WGA At Odds Over 'Whiplash' Screenplay; Will It Hurt Oscar Chances?".Deadline Hollywood.Archivedfrom the original on June 12, 2018.RetrievedDecember 28,2017.

- ^Britton, Luke Morgan (February 17, 2016)."NME Awards 2016 with Austin, Texas full winners list".NME.

- ^"The 100 Greatest Movies of the 21st Century".March 18, 2020.

- ^"Alliance of Women Directors Announces Inaugural Rising Director Fellowship Class – Film News in Brief".Variety.January 16, 2024.RetrievedFebruary 26,2024.

- ^Bergeson, Samantha (January 16, 2024)."'Whiplash' Named Top Sundance Film of All Time in Festival Poll of Over 500 Filmmakers and Critics ".IndieWire.RetrievedFebruary 26,2024.