American Graffitiis a 1973 Americancoming-of-agecomedy-drama filmdirected byGeorge Lucas,produced byFrancis Ford Coppola,written byWillard Huyck,Gloria Katzand Lucas, and starringRichard Dreyfuss,Ron Howard,Paul Le Mat,Charles Martin Smith,Candy Clark,Mackenzie Phillips,Cindy WilliamsandWolfman Jack.Harrison FordandBo Hopkinsalso appear. Set inModesto, California,in 1962, the film is a study of thecruisingand earlyrock 'n' rollcultures popular among Lucas's age group at that time. Through a series ofvignettes,it tells the story of a group of teenagers and their adventures throughout a single night.

| American Graffiti | |

|---|---|

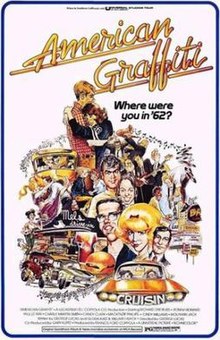

Theatrical release poster byMort Drucker | |

| Directed by | George Lucas |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $777,000[1] |

| Box office | $140 million[1] |

While Lucas was working on his first film,THX 1138,Coppola asked him to write a coming-of-age film. The genesis ofAmerican Graffititook place in Modesto in the early 1960s, during Lucas's teenage years. He was unsuccessful inpitchingthe concept to financiers and distributors but found favor atUniversal Picturesafter every other major film studio turned him down. Filming began inSan Rafael, California,but the production crew was denied permission to shoot beyond a second day. As a result, production was moved toPetaluma, California.[2][3]The film is the first movie to be produced by hisLucasfilmproduction banner.

American Graffitipremiered on August 2, 1973, at theLocarno International Film Festivalin Switzerland, and was released on August 11, 1973, in the United States. The film received widespread critical acclaim and was nominated for theAcademy Award for Best Picture.Produced on a $777,000 budget (equivalent to approximately $5,332,993 in 2023[4]dollars), it has become one of the most profitable films ever. Since its initial release,American Graffitihas earned an estimated return well over $200 million in box-office gross and home video sales, not including merchandising. In 1995, the film was selected for preservation in theNational Film Registry.

Plot

editOn their last evening ofsummer vacationin 1962, high school graduates Curt Henderson and Steve Bolander meet two other friends, confidentdrag-racingking John Milner and unpopular but well-meaning Terry "The Toad" Fields in the parking lot ofMel's Drive-IninModesto, California.Steve and Curt are to travel "Back East"in the morning and start college but the latter has second thoughts about leaving. Laurie, Steve's girlfriend and Curt's sister, arrive moments later, and Steve suggests to her that they see other people while he is away at college to" strengthen "their relationship. Though not openly upset at first, it affects her interactions with him through the night.

Curt, Steve, and Laurie attend the high schoolsock hop.En route, Curt sees a beautiful blonde woman driving a whiteFord Thunderbirdnext to them, who mouths "I love you" before turning right. The interaction causes Curt to desperately search for her throughout the night. After leaving the hop, he is coerced into joining a group ofgreaserscalled "The Pharaohs", who force him to aid them in stealing coins from arcade machines and hooking a chain to a police car, ripping out its back axle. During a tense ride, the Pharaoh leader tells Curt that "The Blonde" is a prostitute, which he does not believe.

With Steve allowing Terry to take care of his car while he's studying at college, Terry uses it to cruise around the strip and pick up the rebellious Debbie. Telling her he is known as "Terry The Tiger", he spends the night trying to impress her, lying about the car being his and purchasing alcohol with no ID. While he and Debbie leave Steve's car in a rural spot to share a romantic interlude, thieves steal the car. Later, after the alcohol has made Terry violently sick, he finds Steve's car and attempts to steal it back. The car thieves appear and beat him up until John intervenes. Terry eventually admits to Debbie that he's been lying about the car all along and he rides a Vespa scooter; she suggests it is "almost a motorcycle" and says she had fun with him, agreeing to meet up with him again.

In an attempt to get cruising company for the evening, John inadvertently picks up Carol, a precocious 12-year-old who manipulates him into driving her around all night. He lies to suspicious friends that she's a cousin and he's stuck with babysitting duty, and they have a series of petty arguments until another car's occupants verbally harass her as she attempts to walk home alone, and John then decides to protect her. Meanwhile, skilled racer Bob Falfa is searching out John to challenge him to the defining race for John's drag-racing crown. During his night of goading anyone he comes across for a challenge, he picks up an emotional Laurie after the argument with Steve that was brewing all night.

After leaving the Pharaohs, Curt drives to the radio station to ask the omnipotent disc jockey "Wolfman Jack"to read a message out on air for the blonde in the White Thunderbird. He encounters an employee who tells him the Wolfman does not work there and that the shows are pre-taped for replay, claiming the Wolfman" is everywhere ". He says the Wolfman would advise Curt to" get your ass in gear "and see the world, but promises to have the Wolfman air the request. As Curt leaves, he notices the employee talking into the microphone and realizes he is the Wolfman, who reads the message for the blonde asking her to call Curt on thepayphoneat Mel's Drive-In.

After taking Carol home, John is found by Bob Falfa, who successfully goads him into the definitive race along Paradise Road outside the city, with spectators appearing to watch. As Terry starts the drag race, John takes the lead, but Bob's tire blows out, causing his car to swerve into a ditch and roll over before bursting into flames. Steve, aware that Laurie was Bob's passenger, rushes to the wreck as she and Bob crawl out and stagger away before the car explodes. While John helps his rival to safety, Laurie begs Steve not to leave her, and he assures her that he will stay with her in Modesto.

Exhausted, Curt is awakened by the payphone. He finally speaks to the blonde, who does not reveal her identity but hints at the possibility of meeting that night. Curt replies that he is leaving town. Later at the airfield, he says goodbye to his parents and friends before boarding the plane. After takeoff, he looks down at the ground from the window and sees the white Thunderbird driving along the road below. Curt thoughtfully gazes into the sky.

A postscript reveals the fates of the four main characters: In 1964, John was killed by a drunk driver; in 1965, Terry was reportedmissing in actionnearAn Lộc,South Vietnam; Steve is an insurance agent in Modesto; and Curt is a writer living in Canada.

Cast

editMain credits

edit- Richard Dreyfussas Curt Henderson

- Ron Howardas Steve Bolander (credited as Ronny Howard)

- Paul Le Matas John Milner

- Charles Martin Smithas Terry "Toad" Fields (credited as Charlie Martin Smith)

- Candy Clarkas Debbie

- Mackenzie Phillipsas Carol

- Cindy Williamsas Laurie Henderson

- Wolfman Jackas the Disc Jockey

- Bo Hopkinsas Joe

- Harrison Fordas Bob Falfa

- Manuel Padilla Jr.as Carlos

- Flash Cadillac & the Continental Kidsas Herby and the Heartbeats

Notable ensemble

edit- Jana Bellan as Budda

- Lynne Marie Stewartas Bobbie

- Deby Celiz as Wendy

- Kathleen Quinlanas Peg

- Scott Beachas Mr. Gordon

- Susan Richardsonas Judy

- Kay Lenzas Jane (credited as Kay Ann Kemper)

- Joe Spanoas Vic

- Debralee Scottas Falfa's Girl

- Del Closeas man at bar

- Suzanne Somersas the blonde in the T-Bird

- Terry McGovernas Mr. Wolfe

Development

editInspiration

editDuring the production ofTHX 1138(1971), producerFrancis Ford Coppolachallenged co-writer/director George Lucas to write a script that would appeal to mainstream audiences.[5]Lucas embraced the idea, using his early 1960s teenage experiencescruisingin Modesto, California. "Cruising was gone, and I felt compelled to document the whole experience and whatmy generationused as a way of meeting girls, "Lucas explained.[5]As he developed the story in his mind, Lucas included his fascination with Wolfman Jack. Lucas had considered doing a documentary about the Wolfman when he attended theUSC School of Cinematic Arts,but he ultimately dropped the idea.[6]

Adding in semiautobiographical connotations, Lucas set the story in his hometown of 1962 Modesto.[5]The characters Curt Henderson, John Milner, and Terry "The Toad" Fields also represent different stages from his younger life. Curt is modeled after Lucas's personality during USC, while John is based on Lucas's teenagedstreet-racingand junior-college years, andhot rodenthusiasts he had known from theKustom Kulturein Modesto. Terry represents Lucas'snerdyears as a freshman in high school, specifically his "bad luck" with dating.[7]The filmmaker was also inspired byFederico Fellini'sI Vitelloni(1953).[8]

After the financial failure ofTHX 1138,Lucas wanted the film to act as a release for a world-weary audience:[9]

[THX] was about real things that were going on and the problems we're faced with. I realized after makingTHXthat those problems are so real that most of us have to face those things every day, so we're in a constant state of frustration. That just makes us more depressed than we were before. So I made a film where, essentially, we can get rid of some of those frustrations, the feeling that everything seems futile.[9]

United Artists

editAfterWarner Bros.abandoned Lucas's early version ofApocalypse Now(during the post-production ofTHX 1138), the filmmaker decided to continue developingAnother Quiet Night in Modesto,eventually changing its title toAmerican Graffiti.[6]To co-write a 15-pagefilm treatment,Lucas hiredWillard HuyckandGloria Katz,who also added semiautobiographical material to the story.[10]Lucas and his colleagueGary KurtzbeganpitchingtheAmerican Graffititreatment to various Hollywood studios and production companies in an attempt to secure the financing needed to expand it into a screenplay,[5]but they were unsuccessful. The potential financiers were concerned thatmusic licensingcosts would cause the film to go way over budget. Along withEasy Rider(1969),American Graffitiwas one of the first films to eschew a traditionalfilm scoreand successfully rely instead on synchronizing a series of popular hit songs with individual scenes.[11]

THX 1138was released in March 1971,[5]and Lucas was offered opportunities to directLady Ice,Tommy,orHair.He turned down those offers, determined to pursue his own projects despite his urgent desire to find another film to direct.[12][13]During this time, Lucas conceived the idea for aspace opera(as yet untitled) which later became the basis for hisStar Warsfranchise. At the1971 Cannes Film Festival,THXwas chosen for theDirectors' Fortnightcompetition. There, Lucas metDavid Picker,then president ofUnited Artists,who was intrigued byAmerican Graffitiand Lucas's space opera. Picker decided to give Lucas $10,000 (equivalent to approximately $75,234 in 2023[4]dollars) to developGraffitias a screenplay.[12]

Lucas planned to spend another five weeks in Europe and hoped that Huyck and Katz would agree to finish the screenplay by the time he returned, but they were about to start on their own film,Messiah of Evil,[10]so Lucas hiredRichard Walter,a colleague from theUSC School of Cinematic Artsfor the job. Walter was flattered, but initially tried to sell Lucas on a different screenplay calledBarry and the Persuasions,a story ofEast Coastteenagers in the late 1950s. Lucas held firm—his was a story aboutWest Coastteenagers in the early 1960s. Walter was paid the $10,000, and he began to expand the Lucas/Huyck/Katz treatment into a screenplay.[12]

Lucas was dismayed when he returned to America in June 1971 and read Walter's script, which was written in the style and tone of anexploitation film,similar to 1967'sHot Rods to Hell."It was overtly sexual and very fantasy-like, withplaying chickenand things that kids didn't really do, "Lucas explained." I wanted something that was more like the way I grew up. "[14]Walter's script also had Steve and Laurie going to Nevada to get married without their parents' permission.[8]Walter rewrote the screenplay, but Lucas nevertheless fired him due to their creative differences.[12]

After paying Walter, Lucas had exhausted his development fund from United Artists. He began writing a script, completing his first draft in just three weeks.[15]Drawing upon his large collection of vintage records, Lucas wrote each scene with a particular song in mind as its musical backdrop.[12]The cost of licensing the 75 songs Lucas wanted was one factor in United Artists' ultimate decision to reject the script; the studio also felt it was too experimental— "a musical montage with no characters". United Artists also passed onStar Wars,which Lucas shelved for the time being.[13]

Universal Pictures

editLucas spent the rest of 1971 and early 1972 trying to raise financing for theAmerican Graffitiscript.[13]During this time,Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer,Paramount Pictures,20th Century Fox,andColumbia Picturesall turned down the opportunity to co-finance and distribute the film.[16]Lucas, Huyck and Katz rewrote the second draft together, which, in addition to Modesto, was also set inMill ValleyandLos Angeles.Lucas also intended to endAmerican Graffitishowing a title card detailing the fate of the characters, including the death of Milner and the disappearance of Toad in Vietnam. Huyck and Katz found the ending depressing and were incredulous that Lucas planned to include only the male characters. Lucas argued that mentioning the girls meant adding another title card, which he felt would prolong the ending. Because of this,Pauline Kaellater accused Lucas ofchauvinism.[16]

Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz took the script toAmerican International Pictures,who expressed interest, but ultimately believedAmerican Graffitiwas not violent or sexual enough for the studio's standards.[17]Lucas and Kurtz eventually found favor atUniversal Pictures,who allowed Lucas totalartistic controland the right offinal cut privilegeon the condition that he makeAmerican Graffition a strict low budget.[13]This forced Lucas to drop the opening scene in which the Blonde Angel, Curt's image of the perfect woman, drives through an empty drive-in cinema in her Ford Thunderbird, her transparency revealing she does not exist.[18]

Universal initially projected a $600,000 budget but added an additional $175,000 once producer Francis Ford Coppola signed on. This would allow the studio to advertiseAmerican Graffitias "from the man who gave youThe Godfather".The proposition also gave Universalfirst-look dealson Lucas's next two planned projects,Star WarsandRadioland Murders.[17]As he continued to work on the script, Lucas encountered difficulties on the Steve and Laurie storyline. Lucas, Katz, and Huyck worked on the third draft together, specifically on the scenes featuring Steve and Laurie.[19]

Production proceeded with virtually no input or interference from Universal sinceAmerican Graffitiwas alow-budget film,and executiveNed Tanenhad only modest expectations of its commercial success. However, Universal did object to the film's title, not knowing what "American Graffiti" meant;[19]Lucas was dismayed when some executives assumed he was making an Italian movie about feet.[16]The studio, therefore, submitted a long list of over 60 alternative titles, with their favorite beingAnother Slow Night in Modesto[19]and Coppola'sRock Around the Block.[16]They pushed hard to get Lucas to adopt any of the titles, but he was displeased with all the alternatives and persuaded Tanen to keepAmerican Graffiti.[19]

Production

editCasting

editThe film's lengthy casting process was overseen byFred Roos,who worked with producer Francis Ford Coppola onThe Godfather.[10]BecauseAmerican Graffiti's main cast was for younger actors, the casting call and notices went through numerous high-school drama groups and community theaters in theSan Francisco Bay Area.[7]Among the actors wasMark Hamill,the futureLuke Skywalkerin Lucas'sStar Warstrilogy.[18]

Over 100 unknown actors auditioned for Curt Henderson before Richard Dreyfuss was cast; George Lucas was impressed with Dreyfuss's thoughtful analysis of the role,[7]and as a result, offered the actor his choice of Curt or Terry "The Toad" Fields.[18]Roos, a former casting director onThe Andy Griffith Show,suggested Ron Howard for Steve Bolander; Howard accepted the role to break out of the mold of his career as a child actor.[7]Howard would later appear in the very similar role ofRichie Cunninghamon theHappy Dayssitcom.[20]Bob Balabanturned down Terry out of fear of becoming typecast, a decision he later regretted. Charles Martin Smith, who, in his first year as a professional actor, had already appeared in two feature films, including 20th Century Fox'sThe Culpepper Cattle Co.and four TV episodes, was eventually cast in the role.[21]

Although Cindy Williams was cast as Laurie Henderson and enjoyed working with both Lucas and Howard,[22]the actress hoped she would get the part of Debbie Dunham, which ended up going to Candy Clark.[10]Mackenzie Phillips,who portrays Carol, was only 12, and under California law, producer Gary Kurtz had to become her legal guardian for the duration of filming.[18]For Bob Falfa, Roos castHarrison Ford,who was then concentrating on a carpentry career. Ford agreed to take the role on the condition that he would not have to cut his hair lest he be offered other movie or TV roles set in the "present day" of the 1970s. The character has a flattop in the script, but a compromise was eventually reached whereby Ford wore aStetsonto cover his hair. Producer Coppola encouraged Lucas to cast Wolfman Jack as himself in acameo appearance."George Lucas and I went through thousands of Wolfman Jack phone calls that were taped with the public," Jack reflected. "The telephone calls [heard on the broadcasts] in the motion picture and on the soundtrack were actual calls with real people."[19][23]

Filming

editAlthoughAmerican Graffitiis set in 1962 Modesto, Lucas believed the city had changed too much in ten years and initially choseSan Rafaelas the primary shooting location.[18]Filming began on June 26, 1972. However, Lucas soon became frustrated at the length of time it was taking to fix camera mounts to the cars.[24]A key member of the production had also been arrested for growing marijuana,[16]and in addition to already running behind theshooting schedule,the San Rafael City Council immediately became concerned about the disruption that filming caused for local businesses, so withdrew permission to shoot beyond a second day.[24]

Petaluma,a similarly small town about 20 miles (32 km) north of San Rafael, was more cooperative, andAmerican Graffitimoved there without the loss of a single day of shooting. Lucas convinced the San Rafael City Council to allow two further nights of filming for general cruising shots, which he used to evoke as much of the intended location as possible in the finished film. Shooting in Petaluma began June 28 and proceeded at a quick pace.[24]Lucas mimicked the filmmaking style ofB-movieproducerSam Katzman(Rock Around the Clock,Your Cheatin' Heart,and the aforementionedHot Rods to Hell) in attempting to save money and authenticated low-budget filming methods.[18]

In addition to Petaluma, other locations includedMel's Drive-Inin San Francisco,Sonoma,Richmond,Novato,and theBuchanan Field AirportinConcord.[25]The freshman hop dance was filmed in the Gus Gymnasium, previously known as the Boys Gym, atTamalpais High SchoolinMill Valley.[26]

More problems ensued during filming; Paul Le Mat was sent to the hospital after an allergic reaction to walnuts. Le Mat, Harrison Ford, and Bo Hopkins were claimed to be drunk most nights and every weekend, and had conducted climbing competitions to the top of the localHoliday Innsign.[27]One actor set fire to Lucas's motel room. Another night, Le Mat threw Richard Dreyfuss into a swimming pool, gashing Dreyfuss's forehead on the day before he was due to have his close-ups filmed. Dreyfuss also complained over the wardrobe that Lucas had chosen for the character. Ford was kicked out of his motel room at the Holiday Inn.[27]In addition, two camera operators were nearly killed when filming the climactic race scene on Frates Road outside Petaluma.[28]Principal photographyended August 4, 1972.[25]

The final scenes in the film, shot at Buchanan Field, feature aDouglas DC-7C airliner of Magic Carpet Airlines, which had previously been leased from owner Club America Incorporated by the rock bandGrand Funk Railroadfrom March 1971 to June 1971.[26][29][30]

Cinematography

editLucas considered covering duties as the sole cinematographer, but dropped the idea.[18]Instead, he elected to shootAmerican Graffitiusing two cinematographers (as he had done inTHX 1138) and no formal director of photography. Two cameras were used simultaneously in scenes involving conversations between actors in different cars, which resulted in significant production time savings.[24]AfterCinemaScopeproved to be too expensive,[18]Lucas decidedAmerican Graffitishould have adocumentary-like feel, so he shot the film usingTechniscopecameras. He believed that Techniscope, an inexpensive way of shooting on35 mm filmand using only half of the film's frame, would give a perfect widescreen format resembling16 mm.Adding to the documentary feel was Lucas's openness for the cast toimprovisescenes. He also usedgoofsfor the final cut, notably Charles Martin Smith's arriving on his scooter to meet Steve outside Mel's Drive-In.[31]Jan D'Alquen and Ron Eveslagewere hired as the cinematographers, but filming with Techniscope cameras brought lighting problems. As a result, Lucas commissioned help from friendHaskell Wexler,who was credited as the "visual consultant".[24]

Editing

editLucas had wanted his then wife,Marcia,to editAmerican Graffiti,but Universal executive Ned Tanen insisted on hiringVerna Fields,who had just finished editingSteven Spielberg'sThe Sugarland Express.[32]Fields worked on the firstrough cutof the film before she left to resume work onWhat's Up, Doc?.After Fields's departure, Lucas struggled with editing the film's story structure. He had originally written the script so that the four (Curt, Steve, John, and Toad) storylines were always presented in the same sequence (an "ABCD" plot structure). The first cut ofAmerican Graffitiwas three and a half hours long, and to whittle the film down to a more manageable two hours, many scenes had to be cut, shortened, or combined. As a result, the film's structure became increasingly loose and no longer adhered to Lucas's original "ABCD" presentation.[31]Lucas completed his final cut ofAmerican Graffiti,which ran 112 minutes, in December 1972.[33]Walter Murchassisted Lucas in post-production foraudio mixingandsound designpurposes.[31]Murch suggested making Wolfman Jack's radio show the "backbone" of the film. "The Wolfman was an ethereal presence in the lives of young people," said producer Gary Kurtz, "and it was that quality we wanted and obtained in the picture."[34]

Soundtrack

editThe choice of music was crucial to the mood of each scene; it isdiegetic musicthat the characters themselves can hear and therefore becomes an integral part of the action.[35]George Lucas had to be realistic about the complexities of copyright clearances, though, and suggested a number of alternative tracks. Universal wanted Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz to hire an orchestra forsound-alikes.The studio eventually proposed a flat deal that offered every music publisher the same amount of money. This was acceptable to most of the companies representing Lucas's first choices, but not toRCA—with the consequence thatElvis Presleyis conspicuously absent from the soundtrack.[13]Clearing themusic licensingrights had cost approximately $90,000,[34]and as a result, no money was left for a traditionalfilm score."I used the absence of music, and sound effects, to create the drama," Lucas later explained.[33]

Asoundtrack albumfor the film,41 Original Hits from the Soundtrack of American Graffiti,was issued byMCA Records.The album contains all the songs used in the film (with the exception of "Gee" by the Crows, which was subsequently included on a second soundtrack album), presented in the order in which they appeared in the film.

Release

editDespite unanimous praise at a January 1973test screeningattended by Universal executive Ned Tanen, the studio told Lucas they wanted to re-edit his original cut ofAmerican Graffiti.[33]Producer Coppola sided with Lucas against Tanen and Universal, offering to "buy the film" from the studio and reimburse it for the $775,000 (equivalent to $5.6 million in 2023)[4]it had cost to make it.[25]20th Century Fox and Paramount Pictures made similar offers to the studio.[6]Universal refused these offers and told Lucas they planned to haveWilliam Hornbeckre-edit the film.[36]

When Coppola'sThe Godfatherwon theAcademy Award for Best Picturein March 1973, Universal relented and agreed to cut only three scenes (amounting to a few minutes) from Lucas's cut. These include an encounter between Toad and a fast-talking car salesman, an argument between Steve and his former teacher Mr. Kroot at the sock hop, and an effort by Bob Falfa to serenade Laurie with "Some Enchanted Evening".The studio initially thought that the film was only fit for release as atelevision movie.[25]

Various studio employees who had seen the film began talking it up, and its reputation grew throughword of mouth.[25]The studio dropped the TV movie idea and began arranging for alimited releasein selected theaters in Los Angeles and New York.[11]Universal presidentsSidney SheinbergandLew Wassermanheard about the praise the film had been garnering in LA and New York, and the marketing department amped up its promotion strategy for it,[11]investing an additional $500,000 (equivalent to $3.4 million in 2023)[4]in marketing and promotion.[6]The film was released in the United States on August 11, 1973[1]tosleeper hitreception.[37]The film had cost only $1.27 million (equivalent to $9.3 million in 2023)[4]to produce and market, but yielded worldwidebox officegross revenues of more than $55 million (equivalent to $377 million in 2023).[4][38]It had only modest success outside the United States and Canada, but became acult filmin France.[36]

Universal reissuedGraffition May 26, 1978, withDolbysound[39][40]and earned an additional $63 million (equivalent to $294 million in 2023),[4]which brought the total revenue for the two releases to $118 million (equivalent to $551 million in 2023).[6][4]The reissue includedstereophonic sound[38]and a couple of minutes the studio had removed from Lucas's original cut.[41]Allhome videoreleases also included these scenes.[25]Also, the date of John Milner's death was changed from June 1964 to December 1964 to fit the narrative structure of the upcoming sequel,More American Graffiti.At the end of its theatrical run,American Graffitihad one of the greatest profit-to-cost ratios of a motion picture ever.[6]

Producer Francis Ford Coppola regretted having not financed the film himself. Lucas recalled, "He would have made $30 million (equivalent to $206 million in 2023)[4]on the deal. He never got over it and he still kicks himself. "[36]It was the 13th-highest-grossing film of all time in 1977[37]and, adjusted for inflation, is currently the 43rd highest.[42]By the 1990s,American Graffitihad earned more than $200 million (equivalent to $466 million in 2023)[4]in box-office gross and home video sales.[6]In December 1997,Varietyreported that the film had earned an additional $55.13 million in rental revenue (equivalent to $105 million in 2023).[4][43]

Universal Studiosfirst released the film on DVD in September 1998,[44]and once more as adouble featurewithMore American Graffiti(1979) in January 2004.[45]The 1978 version of the film was used, with an additional digital change to the sky in the opening title sequence.[41]Additionally, the 1998 DVD and VHS releases were bothTHXcertified as well.[46]Universal released the film onBlu-raywith a new digitally remastered picture supervised by George Lucas on May 31, 2011.[47][48]In celebration of its 50th anniversary, a4Krestoration of the film updated with a brand new5.1 sound mixwas re-released domestically on August 27 and 30 before aUltra HD Blu-rayrelease on November 7, 2023.[49]

Reception

editAmerican Graffitireceived widespread critical acclaim.Roger Ebertgave the film a full four stars and praised it for being "not only a great movie, but a brilliant work of historical fiction; no sociological treatise could duplicate the movie's success in remembering exactly how it was to be alive at that cultural instant".[50]Gene Siskelawarded three-and-a-half stars out of four, writing that although the film suffered from an "overkill" of nostalgia, particularly with regards to a soundtrack so overstuffed that it amounted to "one of those golden-oldie TV blurbs," it was still "well-made, does achieve moments of genuine emotion, and does provide a sock (hop) full of memories."[51]

Vincent CanbyofThe New York Timeswrote, "American Graffitiis such a funny, accurate movie, so controlled and efficient in its narrative, that it stands to be overpraised to the point where seeing it will be an anticlimax. "[52]A.D. Murphy fromVarietyfeltAmerican Graffitiwas a vivid "recall of teenage attitudes and morals, told with outstanding empathy and compassion through an exceptionally talented cast of unknown actors".[53]Charles ChamplinofThe New York Timescalled it a "masterfully executed and profoundly affecting movie."[54]Jay CocksofTimemagazine wrote thatAmerican Graffiti"reveals a new and welcome depth of feeling. Few films have shown quite so well the eagerness, the sadness, the ambitions and small defeats of a generation of young Americans."[55]Pauline KaelofThe New Yorkerwas less enthused, writing that the film "fails to be anything more than a warm, nice, draggy comedy, because there's nothing to back up the style. The images aren't as visually striking as they would be if only there were a mind behind them; the movie has no resonance except from the jukebox sound and the eerie, nocturnal jukebox look." She also noted with disdain that the epilogue did not bother to mention the fates of any of the women characters.[56]Dave Kehr,writing in theChicago Reader,called the film a brilliant work of popular art that redefined nostalgia as a marketable commodity, while establishing a new narrative style.[57]

Based on 62 reviews collected byRotten Tomatoes,95% of the critics enjoyed the film with an average score of 8.6/10. The consensus reads: "One of the most influential of all teen films,American Graffitiis a funny, nostalgic, and bittersweet look at a group of recent high school grads' last days of innocence. "[58]Metacriticcalculated a score of 97 out of 100, indicating "universal acclaim".[59]

Themes

editAmerican Graffitidepicts multiple characters going through acoming of age,such as the decisions to attend college or reside in a small town.[10]The 1962 setting represents nearing an end of an era in American society and pop culture. The early 1960s musical backdrop also links between the early years of rock 'n' roll in the mid- to late 1950s (i.e.,Bill Haley & His Comets,Elvis Presley,andBuddy Holly), and mid-1960s, beginning with the January 1964 arrival ofThe Beatlesand the followingBritish Invasion,whichDon McLean's "American Pie"and the early 1970s revival of 1950s acts and oldies paralleled during the conception and filming.

The setting is two months before theCuban Missile Crisis,and before the outbreak of theVietnam Warand theJohn F. Kennedy assassination[10]and before the peak years of thecounterculture movement.American Graffitievokes mankind's relationship with machines, notably the elaborate number ofhot rods—having been called a "classic-car flick", representative of the motor car's importance to American culture at the time it was made.[60]Another theme is teenagers' obsession with radio, especially with the inclusion of Wolfman Jack and his mysterious and mythological faceless (to most) voice.

Accolades

editThe film is recognized byAmerican Film Institutein these lists:

- 1998:AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies– #77[70]

- 2000:AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs– #43[71]

- 2007:AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)– #62[72]

Legacy

editInternet reviewer MaryAnn Johanson acknowledged thatAmerican Graffitirekindled public and entertainment interest in the 1950s and early 1960s, and influenced other films such asThe Lords of Flatbush(1974) andCooley High(1975) and the TV seriesHappy Days.[73]Alongside other films from theNew Hollywoodera,American Graffitiis often cited for helping give birth to thesummer blockbuster.[74]The film's box-office success made George Lucas an instant millionaire. He gave an amount of the film's profits toHaskell Wexlerfor his visual consulting help during filming, and to Wolfman Jack for "inspiration". Lucas's net worth was now $4 million, and he set aside a $300,000 independent fund for his long-cherished space opera project, which would eventually become the basis forStar Wars(1977).[25]

The financial success ofGraffitialso gave Lucas opportunities to establish more elaborate development forLucasfilm,Skywalker Sound,andIndustrial Light & Magic.[38]Based on the success of the 1978reissue,Universal began production for the sequelMore American Graffiti(1979).[6]Lucas and writers Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz later collaborated onHoward the Duck(1986) andRadioland Murders(1994). They were both released by Universal Pictures, for which Lucas acted as executive producer.Radioland Murdersfeatures characters intended to be Curt and Laurie Henderson's parents, Roger and Penny Henderson.[38]In 1995,American Graffitiwas deemed culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant by the United StatesLibrary of Congressand selected for preservation in theNational Film Registry.[75]In 1997 the city ofModesto, California(where the film largely takes place), honored Lucas with a statue dedication ofAmerican Graffitiat George Lucas Plaza.[5]Furthermore, the city has anannual classic car festivalin honor of its graffiti culture heritage.

DirectorDavid FinchercreditedAmerican Graffitias a visual influence forFight Club(1999).[76]Lucas'sStar Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones(2002) features references to the film. The yellowairspeederthatAnakin SkywalkerandObi-Wan Kenobiuse to pursue bounty hunterZam Wesellis based on John Milner's yellowdeuce coupe,[77]while Dex's Diner is reminiscent ofMel's Drive-In.[78]Adam SavageandJamie Hynemanconducted the "rear axle" experiment on the January 11, 2004, episode ofMythBusters.[79]

Given the popularity of the film's cars withcustomizersandhot roddersin the years since its release, their fate immediately after the film is surprising. All were offered for sale in San Francisco newspaper ads; only the'58 Impala(driven by Ron Howard) attracted a buyer, selling for only a few hundred dollars. The yellow Deuce coupe and the Pharaohs red Mercury went unsold, despite the coupe being priced as low as $1500.[80]The registration plate on Milner's yellow deuce coupe is THX 138 on a yellow, California license plate, slightly altered, reflecting Lucas's earlier science-fiction film (THX 1138).

See also

editReferences

edit- ^abc"American Graffiti (1973) – Financial Information".The Numbers.Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2015.RetrievedJanuary 30,2012.

- ^Mabry, Jennifer (August 9, 2023)."'American Graffiti' at 50: An oral history of 'the quintessential hot rod movie'".Los Angeles Times.RetrievedJune 18,2024.

Although "American Graffiti" is set in Modesto, in California's Central Valley, the film was shot in Petaluma...

- ^Roeper, Richard (August 24, 2023)."50 years ago, 'American Graffiti' showed '70s audiences a simpler time".Chicago Sun-Times.RetrievedJune 18,2024.

Although the story is set in Modesto, the majority of filming actually took place in Petaluma, California.... Filming also took place in San Rafael (the city council withdrew permits after one day)...

- ^abcdefghijk1634–1699:McCusker, J. J.(1997).How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda(PDF).American Antiquarian Society.1700–1799:McCusker, J. J.(1992).How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States(PDF).American Antiquarian Society.1800–present:Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis."Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–".RetrievedFebruary 29,2024.

- ^abcdefHearn, pp. 10–11, 42–47

- ^abcdefghBaxter, pp. 70, 104, 148, 254

- ^abcdHearn, pp. 56–57

- ^abBaxter, pp. 106–118

- ^abSturhahn, Larry (March 1974). "The Filming ofAmerican Graffiti".Filmmakers Newsletter.

- ^abcdef(DVD)The Making of American Graffiti.Universal Studios Home Entertainment.1998.

- ^abcKen Plume (November 11, 2002)."An Interview with Gary Kurtz".IGN.Archivedfrom the original on June 29, 2009.RetrievedApril 30,2009.

- ^abcdeHearn, pp. 52–53

- ^abcdeHearn, pp. 54–55

- ^"A Life Making Movies".Academy of Achievement.June 19, 1999. Archived fromthe originalon May 9, 2008.RetrievedApril 22,2008.

- ^Echarri, Miquel (May 18, 2023)."Fires, alcohol and an out-of-control Harrison Ford: 50 years later, the making of 'American Graffiti' has not been forgotten".EL PAÍS English.RetrievedMay 21,2023.

- ^abcdePollock, pp. 105–111

- ^abBaxter, pp. 120–123

- ^abcdefghBaxter, pp. 124–128

- ^abcdeHearn, pp. 58–60

- ^Brooks, Victor (2012).Last Season of Innocence: The Teen Experience in the 1960s By Victor Brooks.Rowman & Littlefield.ISBN9781442209176.Archivedfrom the original on June 9, 2015.RetrievedJanuary 21,2015.

Happy Days began airing only a few months after Graffiti came out, and much of the plotline revolved around Howard's character, Richie Cunningham, who was almost an exact clone of Steve in the film.

- ^"The Hardest Working Actors in Showbiz".Entertainment Weekly.October 17, 2008.Archivedfrom the original on April 25, 2009.RetrievedMay 9,2009.

- ^"Cindy Williams on working with George Lucas on" American Graffiti "- EMMYTVLEGENDS.ORG"(Interview). Interviewed by Amy Harrington. FoundationINTERVIEWS (published January 27, 2016). August 7, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on February 24, 2020.RetrievedAugust 3,2019– viaYouTube.

- ^"50 years ago, 'American Graffiti' showed '70s audiences a simpler time".August 24, 2023.

- ^abcdeHearn, pp. 61–63

- ^abcdefgHearn, pp. 70–75

- ^abAmerican Graffiti Filming Locations (June – August 1972)ArchivedNovember 20, 2010, at theWayback Machine

- ^abBaxter, p. 129.

- ^Baxter, pp. 129–130.

- ^"Douglas DC-6 and DC-7 Tankers".Archivedfrom the original on November 8, 2010.RetrievedJanuary 16,2011.

- ^"American Graffiti".Archivedfrom the original on July 21, 2011.RetrievedJanuary 16,2011.

- ^abcHearn, pp. 64–66

- ^Baxter, pp. 132–135.

- ^abcHearn, pp. 67–69

- ^abBaxter, pp. 129–135.

- ^"Richards, Mark. 'Diegetic Music, Non-Diegetic Music, and" Source Scoring "' inFilm Music Notes,21 April 2013 ".May 4, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on February 7, 2020.RetrievedApril 11,2020.

- ^abcPollock, pp. 120–128

- ^ab"American Graffiti".Box Office Mojo.Archivedfrom the original on April 16, 2009.RetrievedMay 3,2009.

- ^abcdHearn, pp. 79–86, 122

- ^"9 New Releases, Plus 'Graffiti,' On U Sked To July".Variety.April 12, 1978. p. 3.

- ^"Holiday Ups L.A.; 'Friday' Boff $277,000, 'Graffiti' Smash 211G, 'Wednesday' Splashy $159,000".Variety.May 31, 1978. p. 8.

- ^abCoate, Michael (August 1, 2013)."Where Were You In '73? Remembering American Graffiti On Its 40th Anniversary".The Digital Bits.RetrievedDecember 27,2021.

- ^"Domestic Grosses Adjusted For Inflation".Box Office Mojo.Archivedfrom the original on May 4, 2009.RetrievedMay 3,2009.

- ^Staff (December 16, 1997)."Rental champs: Rate of return".Variety.Archivedfrom the original on January 22, 2012.RetrievedMay 3,2009.

- ^American Graffiti (1973).ISBN078322737X.

- ^"American Graffiti / More American Graffiti (Drive-In Double Feature) (1979)".Amazon.com.January 20, 2004.Archivedfrom the original on April 10, 2016.RetrievedMay 3,2009.

- ^Halperin, Frank (November 6, 1998)."A silver anniversary".Courier-Post.p. 79.Archivedfrom the original on August 29, 2024.RetrievedAugust 29,2024– viaNewspapers.com.

- ^"'American Graffiti' Blu-ray Detailed ".High-Def Digest.Archivedfrom the original on May 8, 2011.RetrievedMay 5,2011.

- ^"American Graffiti (Special Edition) [Blu-ray] (1973)".Amazon.com.Archivedfrom the original on April 10, 2016.RetrievedMay 5,2011.

- ^"Watch American Graffiti in 4K Ultra HD and with Fathom Events".Lucasfilm.August 3, 2023.RetrievedMarch 16,2024.

- ^Roger Ebert(August 11, 1973)."American Graffiti".Chicago Sun-Times.Archivedfrom the original on June 2, 2013.RetrievedMay 5,2009.

- ^Siskel, Gene(August 24, 1973). "'Graffiti'—How many golden oldies can you handle?"Chicago Tribune.Section 2, p. 1.

- ^Canby, Vincent(September 16, 1973). "'Heavy Traffic' and 'American Graffiti'-Two of the Best".The New York Times.Section 2, p. 1, 3.

- ^A.D. Murphy (June 20, 1973)."American Graffiti".Variety.Archivedfrom the original on June 22, 2011.RetrievedMay 5,2009.

- ^Champlin, Charles(July 29, 1973). "A New Generation Looks-Back in 'Graffiti'".Los Angeles Times.Calendar, p. 1.

- ^Jay Cocks(August 20, 1973)."Fabulous '50s".Time.Archived fromthe originalon June 15, 2009.RetrievedMay 5,2009.

- ^Kael, Pauline(October 29, 1973). "The Current Cinema".The New Yorker.154–155.

- ^Dave Kehr."American Graffiti".Chicago Reader.Archivedfrom the original on October 14, 2008.RetrievedMay 5,2009.

- ^"American Graffiti".Rotten Tomatoes.Fandango.Archivedfrom the original on June 4, 2020.RetrievedOctober 5,2021.

- ^American Graffiti,retrievedJuly 6,2021

- ^Badger, Emily."What the Steamship and the Landline Can Tell Us About the Decline of the Private Car".The Atlantic Cities.Archivedfrom the original on April 3, 2013.RetrievedApril 4,2013.

- ^"The 46th Academy Awards (1974) Nominees and Winners".oscars.org.Archivedfrom the original on March 15, 2015.RetrievedDecember 31,2011.

- ^"BAFTA Awards: Film in 1975".BAFTA.1975.RetrievedJune 3,2021.

- ^"26th DGA Awards".Directors Guild of America Awards.RetrievedJuly 5,2021.

- ^"American Graffiti – Golden Globes".HFPA.RetrievedJune 3,2021.

- ^"KCFCC Award Winners – 1970-79".kcfcc.org.December 14, 2013.RetrievedMay 15,2021.

- ^"Past Awards".National Society of Film Critics.December 19, 2009.RetrievedJuly 5,2021.

- ^"1973 New York Film Critics Circle Awards".New York Film Critics Circle.RetrievedJune 3,2021.

- ^"Film Hall of Fame Inductees: Productions".Online Film & Television Association.RetrievedAugust 15,2021.

- ^"Awards Winners".wga.org.Writers Guild of America.RetrievedNovember 24,2023.

- ^"AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies"(PDF).American Film Institute.Archived(PDF)from the original on April 12, 2019.RetrievedAugust 6,2016.

- ^"AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs"(PDF).American Film Institute.Archived(PDF)from the original on March 16, 2013.RetrievedAugust 6,2016.

- ^"AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)"(PDF).American Film Institute.Archived(PDF)from the original on June 6, 2013.RetrievedAugust 6,2016.

- ^MaryAnn Johanson (June 16, 1999)."Boy Meets World".The Flick Filosopher.Archivedfrom the original on June 16, 2009.RetrievedMay 8,2009.

- ^Staff (May 24, 1991)."The Evolution of the Summer Blockbuster".Entertainment Weekly.Archivedfrom the original on April 21, 2009.RetrievedFebruary 26,2008.

- ^"National Film Registry: 1989–2007".National Film Registry.Archivedfrom the original on May 1, 2008.RetrievedMay 9,2008.

- ^Staff (August 13, 1999)."Movie Preview: Oct. 15".Entertainment Weekly.Archivedfrom the original on June 15, 2009.RetrievedFebruary 26,2008.

- ^"Anakin Skywalker's Airspeeder".StarWars.com.Archived fromthe originalon December 6, 2004.RetrievedJanuary 19,2008.

- ^"Dex's Diner".StarWars.com.Archived fromthe originalon October 13, 2007.RetrievedJanuary 19,2008.

- ^"Explosive Decompression/Frog Giggin'/Rear Axle".Adam Savage,Jamie Hyneman.MythBusters.January 11, 2004. No. 13, season 1.

- ^Rod and CustomMagazine, 12/91, pp. 11–12.

Bibliography

edit- John Baxter(1999).Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas.New York City: Spike Books.ISBN0-380-97833-4.

- Marcus Hearn (2005).The Cinema of George Lucas.New York City:ABRAMS Books.ISBN0-8109-4968-7.

- Dale Pollock (1999).Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas.New York City:Da Capo Press.ISBN0-306-80904-4.

External links

edit- Official website

- American GraffitiatIMDb

- American GraffitiatAllMovie

- American GraffitiatBox Office Mojo

- American GraffitiatRotten Tomatoes

- American Graffitiat theAFI Catalog of Feature Films

- American Graffitiat theTCM Movie Database

- American GraffitiFilmsite.org

- The City of Petaluma's salute toAmerican Graffiti

- "Star Wars: The Year's Best Movie".Time.May 30, 1977. Archived fromthe originalon November 14, 2010.RetrievedNovember 16,2010.

- American Graffitiessay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010ISBN0826429777,pages 693-694[1]