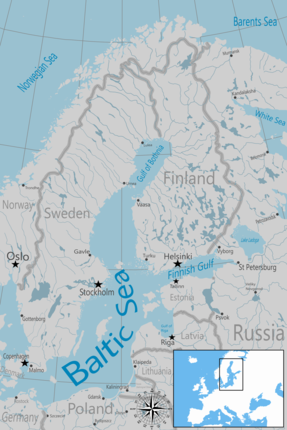

TheBaltic Seais an arm of theAtlantic Oceanthat is enclosed byDenmark,Estonia,Finland,Germany,Latvia,Lithuania,Poland,Russia,Sweden,and theNorthand CentralEuropean Plain.[3]

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 10°E to 30°E longitude. It is ashelf seaandmarginal seaof the Atlantic with limited water exchange between the two, making it aninland sea.The Baltic Sea drains through theDanish straitsinto theKattegatby way of theØresund,Great BeltandLittle Belt.It includes theGulf of Bothnia(divided into theBothnian Bayand theBothnian Sea), theGulf of Finland,theGulf of Rigaand theBay of Gdańsk.

The "Baltic Proper"is bordered on its northern edge, at latitude 60°N, byÅlandand the Gulf of Bothnia, on its northeastern edge by the Gulf of Finland, on its eastern edge by the Gulf of Riga, and in the west by the Swedish part of the southern Scandinavian Peninsula.

The Baltic Sea is connected byartificial waterwaysto theWhite Seavia theWhite Sea–Baltic Canaland to theGerman Bightof theNorth Seavia theKiel Canal.

Definitions

editAdministration

editTheHelsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Areaincludes the Baltic Sea and theKattegat,without calling Kattegat a part of the Baltic Sea, "For the purposes of this Convention the 'Baltic Sea Area' shall be the Baltic Sea and the Entrance to the Baltic Sea, bounded by the parallel of the Skaw in the Skagerrak at 57°44.43'N."[4]

Traffic history

editHistorically, theKingdom of DenmarkcollectedSound Duesfrom ships at the border between the ocean and the land-locked Baltic Sea, in tandem: in theØresundatKronborgcastle nearHelsingør;in theGreat BeltatNyborg;and in theLittle Beltat its narrowest part thenFredericia,after that stronghold was built. The narrowest part of Little Belt is the "Middelfart Sund" nearMiddelfart.[5]

Oceanography

editGeographers widely agree that the preferred physical border between the Baltic and North Seas is the Langelandsbælt (the southern part of theGreat Beltstrait nearLangeland) and theDrogden-Sill strait.[6]The Drogden Sill is situated north ofKøge Bugtand connectsDragørin the south ofCopenhagentoMalmö;it is used by theØresund Bridge,including theDrogden Tunnel.By this definition, theDanish straitsis part of the entrance, but theBay of Mecklenburgand theBay of Kielare parts of the Baltic Sea. Another usual border is the line betweenFalsterbo,Sweden, andStevns Klint,Denmark, as this is the southern border of Øresund. It is also the border between the shallow southern Øresund (with a typical depth of 5–10 meters only) and notably deeper water.

Hydrography and biology

editDrogdenSill (depth of 7 m (23 ft)) sets a limit to Øresund andDarssSill (depth of 18 m (59 ft)), and a limit to the Belt Sea.[7]The shallowsillsare obstacles to the flow of heavy salt water from the Kattegat into the basins aroundBornholmandGotland.

The Kattegat and the southwestern Baltic Sea are well oxygenated and have a rich biology. The remainder of the Sea is brackish, poor in oxygen, and in species. Thus, statistically, the more of the entrance that is included in its definition, the healthier the Baltic appears; conversely, the more narrowly it is defined, the more endangered its biology appears.

Etymology and nomenclature

editTacituscalled it the Suebic Sea, Latin:Mare Suebicumafter theGermanic peopleof theSuebi,[8][9]andPtolemySarmatianOceanafter theSarmatians,[10]but the first to name it theBaltic Sea(Medieval Latin:Mare Balticum) was the eleventh-century German chroniclerAdam of Bremen.The origin of the latter name is speculative and it was adopted intoSlavicandFinnic languagesspoken around the sea, very likely due to the role ofMedieval Latinincartography.It might be connected to the Germanic wordbelt,a name used for two of the Danish straits,the Belts,while others claim it to be directly derived from the source of the Germanic word,Latinbalteus"belt".[11]Adam of Bremenhimself compared the sea with a belt, stating that it is so named because it stretches through the land as a belt (Balticus, eo quod in modum baltei longo tractu perScithicasregiones tendatur usque inGreciam).

He might also have been influenced by the name of a legendary island mentioned in theNatural HistoryofPliny the Elder.Pliny mentions an island namedBaltia(orBalcia) with reference to accounts ofPytheasandXenophon.It is possible that Pliny refers to an island named Basilia ( "the royal" ) inOn the Oceanby Pytheas.Baltiaalso might be derived from "belt", and therein mean "near belt of sea, strait".[citation needed]

Others have suggested that the name of the island originates from theProto-Indo-Europeanroot*bʰelmeaning "white, fair",[12]which may echo the naming of seas after colours relating to the cardinal points (as perBlack SeaandRed Sea).[13]This '*bʰel' root and basic meaning were retained inLithuanian(asbaltas),Latvian(asbalts) andSlavic(asbely). On this basis, a related hypothesis holds that the name originated from this Indo-European root via aBaltic languagesuch as Lithuanian.[14]Another explanation is that, while derived from the aforementioned root, the name of the sea is related to names for various forms of water and related substances in several European languages, that might have been originally associated with colors found in swamps (compare Proto-Slavic*bolto"swamp" ). Yet another explanation is that the name originally meant "enclosed sea, bay" as opposed to open sea.[15]

In theMiddle Agesthe sea was known by a variety of names. The name Baltic Sea became dominant after 1600. Usage ofBalticand similar terms to denote the region east of the sea started only in the 19th century.[citation needed]

Name in other languages

editThe Baltic Sea was known in ancient Latin language sources asMare Suebicumor evenMare Germanicum.[16]Older native names in languages that used to be spoken on the shores of the sea or near it usually indicate the geographical location of the sea (in Germanic languages), or its size in relation to smaller gulfs (in Old Latvian), or tribes associated with it (in Old Russian the sea was known as the Varanghian Sea). In modern languages, it is known by the equivalents of "East Sea", "West Sea", or "Baltic Sea" in different languages:

- "Baltic Sea"is used in Modern English; in theBaltic languagesLatvian(Baltijas jūra;in Old Latvian it was referred to as "the Big Sea", while the present day Gulf of Riga was referred to as "the Little Sea" ) andLithuanian(Baltijos jūra); inLatin(Mare Balticum) and theRomance languagesFrench(Mer Baltique),Italian(Mar Baltico),Portuguese(Mar Báltico),Romanian(Marea Baltică) andSpanish(Mar Báltico); inGreek(Βαλτική ΘάλασσαValtikí Thálassa); inAlbanian(Deti Balltik); inWelsh(Môr Baltig); in theSlavic languagesPolish(Morze BałtyckieorBałtyk),Czech(Baltské mořeorBalt),Slovenian(Baltsko morje),Bulgarian(Балтийско мореBaltijsko More),Kashubian(Bôłt),Macedonian(Балтичко МореBaltičko More),Ukrainian(Балтійське мореBaltijs′ke More),Belarusian(Балтыйскае мораBaltyjskaje Mora),Russian(Балтийское мореBaltiyskoye More) andSerbo-Croatian(Baltičko more/Балтичко море); inHungarian(Balti-tenger).

- InGermanic languages,except English,"East Sea"is used, as inAfrikaans(Oossee),Danish(Østersøen[ˈøstɐˌsøˀn̩]),Dutch(Oostzee),German(Ostsee),Low German(Oostsee),IcelandicandFaroese(Eystrasalt),Norwegian(Bokmål:Østersjøen[ˈø̂stəˌʂøːn];Nynorsk:Austersjøen), andSwedish(Östersjön). InOld Englishit was known asOstsǣ,[17]which does not however mean 'east sea' and may be related to a people known in the same work as theOsti.[18]Also inHungarianthe former name wasKeleti-tenger( "East-sea", due to German influence). In addition,Finnish,aFinnic language,uses the termItämeri"East Sea", possibly acalquefrom a Germanic language. As the Baltic is not particularly eastward in relation to Finland, the use of this term may be a leftover from the period of Swedish rule.

- In another Finnic language,Estonian,it is called the"West Sea"(Läänemeri), with the correct geography (the sea is west of Estonia). InSouth Estonian,it has the meaning of both"West Sea"and"Evening Sea"(Õdagumeri). In the endangeredLivonian languageof Latvia, the sea (and sometimes theIrbe Straitas well) is called the"Large Sea"(Sūŗ meŗorSūr meŗ).[19][20]

History

editClassical world

editAt the time of theRoman Empire,the Baltic Sea was known as theMare SuebicumorMare Sarmaticum.Tacitusin his AD 98AgricolaandGermaniadescribed the Mare Suebicum, named for theSuebitribe, during the spring months, as abrackishsea where the ice broke apart and chunks floated about. The Suebi eventually migrated southwest to temporarily reside in the Rhineland area of modern Germany, where their name survives in the historic region known asSwabia.Jordanescalled it theGermanic Seain his work, theGetica.[citation needed]

Middle Ages

editIn the earlyMiddle Ages,Norse (Scandinavian) merchants built a trade empire all around the Baltic. Later, the Norse fought for control of the Baltic againstWendish tribesdwelling on the southern shore. The Norse also used the rivers ofRussiafor trade routes, finding their way eventually to theBlack Seaand southern Russia. This Norse-dominated period is referred to as theViking Age.[citation needed]

Since theViking Age,the Scandinavians have referred to the Baltic Sea asAustmarr( "Eastern Lake" ). "Eastern Sea", appears in theHeimskringlaandEystra saltappears inSörla þáttr.Saxo Grammaticusrecorded inGesta Danoruman older name,Gandvik,-vikbeingOld Norsefor "bay", which implies that the Vikings correctly regarded it as an inlet of the sea. Another form of the name, "Grandvik", attested in at least one English translation ofGesta Danorum,is likely to be a misspelling.[citation needed]

In addition to fish the sea also providesamber,especially from its southern shores within today's borders ofPoland,RussiaandLithuania.First mentions of amber deposits on the South Coast of the Baltic Sea date back to the 12th century.[21]The bordering countries have also traditionally exported lumber,wood tar,flax,hempand furs by ship across the Baltic. Sweden had from early medieval times exportedironandsilvermined there, while Poland had and still has extensivesaltmines. Thus, the Baltic Sea has long been crossed by much merchant shipping.[citation needed]

The lands on the Baltic's eastern shore were among the last in Europe to be converted toChristianity.This finally happened during theNorthern Crusades:Finlandin the twelfth century by Swedes, and what are nowEstoniaandLatviain the early thirteenth century by Danes and Germans (Livonian Brothers of the Sword). TheTeutonic Ordergained control over parts of the southern and eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, where they set uptheir monastic state.Lithuaniawasthe last European state to convert to Christianity.[citation needed]

An arena of conflict

editIn the period between the 8th and 14th centuries, there was much piracy in the Baltic from the coasts ofPomeraniaandPrussia,and theVictual BrothersheldGotland.[citation needed]

Starting in the 11th century, the southern and eastern shores of the Baltic were settled by migrants mainly fromGermany,a movement called theOstsiedlung( "east settling" ). Other settlers were from theNetherlands,Denmark,andScotland.ThePolabian Slavswere gradually assimilated by the Germans.[22]Denmarkgradually gained control over most of the Baltic coast, until she lost much of her possessions after being defeated in the 1227Battle of Bornhöved.[citation needed]

In the 13th to 16th centuries, the strongest economic force in Northern Europe was theHanseatic League,a federation of merchant cities around the Baltic Sea and theNorth Sea.In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries,Poland,Denmark,andSwedenfought wars forDominium maris baltici( "Lordship over the Baltic Sea" ). Eventually, it was Sweden thatvirtually encompassed the Baltic Sea.In Sweden, the sea was then referred to asMare Nostrum Balticum( "Our Baltic Sea" ). The goal of Swedish warfare during the 17th century was to make the Baltic Sea an all-Swedish sea (Ett Svenskt innanhav), something that was accomplished except the part between Riga in Latvia andStettinin Pomerania. However, theDutchdominated the Baltic trade in the seventeenth century.[citation needed]

In the eighteenth century,RussiaandPrussiabecame the leading powers over the sea. Sweden's defeat in theGreat Northern Warbrought Russia to the eastern coast. Russia became and remained a dominating power in the Baltic. Russia'sPeter the Greatsaw the strategic importance of the Baltic and decided to found his new capital,Saint Petersburg,at the mouth of theNevariver at the east end of theGulf of Finland.There was much trading not just within the Baltic region but also with the North Sea region, especially easternEnglandand theNetherlands:their fleets needed the Baltic timber, tar, flax, and hemp.[citation needed]

During theCrimean War,a joint British and French fleet attacked the Russian fortresses in the Baltic; the case is also known as theÅland War.They bombardedSveaborg,which guardsHelsinki;andKronstadt,which guards Saint Petersburg; and they destroyedBomarsundinÅland.After the unification ofGermanyin 1871, the whole southern coast became German.World War Iwas partly fought in the Baltic Sea. After 1920Polandwas granted access to the Baltic Sea at the expense of Germany by thePolish Corridorand enlarged the port ofGdyniain rivalry with the port of theFree City of Danzig.[citation needed]

After the Nazis' rise to power, Germany reclaimed theMemellandand after the outbreak of theEastern Front (World War II)occupied the Baltic states. In 1945, the Baltic Sea became a mass grave for retreating soldiers and refugees on torpedoedtroop transports.The sinking of theWilhelm Gustloffremains the worst maritime disaster in history, killing (very roughly) 9,000 people. In 2005, a Russian group of scientists found over five thousand airplane wrecks, sunken warships, and other material, mainly from World War II, on the bottom of the sea.[citation needed]

Since World War II

editSince the end ofWorld War II,various nations, including theSoviet Union,the United Kingdom and the United States have disposed ofchemical weaponsin the Baltic Sea, raising concerns of environmental contamination.[23]Today, fishermen occasionally find some of these materials: the most recent available report from the Helsinki Commission notes that four small scale catches of chemical munitions representing approximately 105 kg (231 lb) of material were reported in 2005. This is a reduction from the 25 incidents representing 1,110 kg (2,450 lb) of material in 2003.[24]Until now, theU.S. Governmentrefuses to disclose the exact coordinates of the wreck sites. Deteriorating bottles leakmustard gasand other substances, thus slowly poisoning a substantial part of the Baltic Sea.[citation needed]

After 1945, theGerman population was expelledfrom all areas east of theOder-Neisse line,making roomfor new Polish and Russian settlement. Polandgained most of the southern shore.The Soviet Union gained another access to the Baltic with theKaliningrad Oblast,that had been part of German-settledEast Prussia.The Baltic states on the eastern shore were annexed by the Soviet Union. The Baltic then separated opposing military blocs:NATOand theWarsaw Pact.Neutral Sweden developedincident weaponsto defend itsterritorial watersafter theSwedish submarine incidents.[25]This border status restricted trade and travel. It ended only after the collapse of theCommunistregimes in Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s. Finland and Sweden joined NATO in 2023 and 2024, respectively, making the Baltic Sea almost entirely surrounded by the alliance's members.[26][27]Such an arrangement has also existed for theEuropean Union(EU) since May 2004 following the accession of the Baltic states and Poland. The remaining non-NATO and -EU shore areas are Russian: the Saint Petersburg area and theKaliningrad Oblastexclave.

Winter storms begin arriving in the region during October. These have caused numerousshipwrecks,and contributed to the extreme difficulties of rescuing passengers of the ferryM/S Estoniaen route fromTallinn,Estonia, toStockholm,Sweden, in September 1994, which claimed the lives of 852 people. Older, wood-based shipwrecks such as theVasatend to remain well-preserved, as the Baltic's cold and brackish water does not suit theshipworm.

Finland and Sweden joining NATO in 2023 and 2024, respectively, led some to label the sea a ″NATO lake″, as all the countries surrounding the Baltic Sea except Russia had become members of NATO.[28][29][27][30]

Storm floods

editStorm surgefloods are generally taken to occur when the water level is more than one metre above normal. In Warnemünde about 110 floods occurred from 1950 to 2000, an average of just over two per year.[31]

Historic flood events were theAll Saints' Flood of 1304and other floods in the years 1320, 1449, 1625, 1694, 1784 and 1825. Little is known of their extent.[32]From 1872, there exist regular and reliable records of water levels in the Baltic Sea. The highest was theflood of 1872when the water was an average of 2.43 m (8 ft 0 in) above sea level at Warnemünde and a maximum of 2.83 m (9 ft 3 in) above sea level in Warnemünde. In the last very heavy floods the average water levels reached 1.88 m (6 ft 2 in) above sea level in 1904, 1.89 m (6 ft 2 in) in 1913, 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in) in January 1954, 1.68 m (5 ft 6 in) on 2–4 November 1995 and 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) on 21 February 2002.[33]

Geography

editGeophysical data

editAn arm of theNorth Atlantic Ocean,the Baltic Sea is enclosed bySwedenandDenmarkto the west,Finlandto the northeast, and theBaltic countriesto the southeast.

It is about 1,600 km (990 mi) long, an average of 193 km (120 mi) wide, and an average of 55 metres (180 ft) deep. The maximum depth is 459 m (1,506 ft) which is on the Swedish side of the center. The surface area is about 349,644 km2(134,998 sq mi)[34]and the volume is about 20,000 km3(4,800 cu mi). The periphery amounts to about 8,000 km (5,000 mi) of coastline.[35]

The Baltic Sea is one of the largestbrackishinland seas by area, and occupies a basin (aZungenbecken) formed by glacial erosion during the last fewice ages.

| Sub-area | Area | Volume | Maximum depth | Average depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | km3 | m | m | |

| Baltic proper | 211,069 | 13,045 | 459 | 62.1 |

| Gulf of Bothnia | 115,516 | 6,389 | 230 | 60.2 |

| Gulf of Finland | 29,600 | 1,100 | 123 | 38.0 |

| Gulf of Riga | 16,300 | 424 | > 60 | 26.0 |

| Belt Sea/Kattegat | 42,408 | 802 | 109 | 18.9 |

| Total Baltic Sea | 415,266 | 21,721 | 459 | 52.3 |

Extent

editTheInternational Hydrographic Organizationdefines the limits of the Baltic Sea as follows:[37]

- Bordered by the coasts of Germany, Denmark, Poland, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, it extends north-eastward of the following limits:

- In theLittle Belt.A line joiningFalshöft(54°47′N9°57.5′E/ 54.783°N 9.9583°E) and Vejsnæs Nakke (Ærø:54°49′N10°26′E/ 54.817°N 10.433°E).

- In theGreat Belt.A line joining Gulstav (South extreme ofLangelandIsland) and Kappel Kirke (54°46′N11°01′E/ 54.767°N 11.017°E) on Island ofLolland.

- In theGuldborg Sound.A line joining Flinthorne-Rev and Skjelby (54°38′N11°53′E/ 54.633°N 11.883°E).

- Inthe Sound.A line joiningStevnsLighthouse (55°17′N12°27′E/ 55.283°N 12.450°E) andFalsterbo Point(55°23′N12°49′E/ 55.383°N 12.817°E).

Subdivisions

edit1 =Bothnian Bay

2 =Bothnian Sea

1 + 2 =Gulf of Bothnia,partly also 3 & 4

3 =Archipelago Sea

4 =Åland Sea

5 =Gulf of Finland

6 = Northern Baltic Proper

7 = WesternGotland Basin

8 = EasternGotland Basin

9 =Gulf of Riga

10 =Bay of Gdańsk/Gdansk Basin

11 =BornholmBasin andHanö Bight

12 =ArkonaBasin

6–12 =Baltic Proper

13 =Kattegat,not an integral part of the Baltic Sea

14 = Belt Sea (Little BeltandGreat Belt)

15 =Öresund(The Sound)

14 + 15 =Danish straits,not an integral part of the Baltic Sea

The northern part of the Baltic Sea is known as theGulf of Bothnia,of which the northernmost part is the Bay of Bothnia orBothnian Bay.The more rounded southern basin of the gulf is calledBothnian Seaand immediately to the south of it lies theSea of Åland.TheGulf of Finlandconnects the Baltic Sea withSaint Petersburg.TheGulf of Rigalies between theLatviancapital city ofRigaand theEstonianisland ofSaaremaa.

The Northern Baltic Sea lies between theStockholmarea, southwestern Finland, and Estonia. TheWestern and Eastern Gotland basinsform the major parts of the Central Baltic Sea or Baltic proper. TheBornholmBasin is the area east of Bornholm, and the shallowerArkonaBasin extends from Bornholm to the Danish isles ofFalsterandZealand.

In the south, theBay of Gdańsklies east of theHel Peninsulaon the Polish coast and west of theSambia PeninsulainKaliningrad Oblast.TheBay of Pomeranialies north of the islands ofUsedom/UznamandWolin,east ofRügen.Between Falster and the German coast lie theBay of MecklenburgandBay of Lübeck.The westernmost part of the Baltic Sea is theBay of Kiel.The threeDanish straits,theGreat Belt,theLittle BeltandThe Sound(Öresund/Øresund), connect the Baltic Sea with theKattegatandSkagerrakstrait in theNorth Sea.

Temperature and ice

editThe water temperature of the Baltic Sea varies significantly depending on exact location, season and depth. At the Bornholm Basin, which is located directly east of the island of the same name, the surface temperature typically falls to 0–5 °C (32–41 °F) during the peak of the winter and rises to 15–20 °C (59–68 °F) during the peak of the summer, with an annual average of around 9–10 °C (48–50 °F).[39]A similar pattern can be seen in theGotland Basin,which is located between the island of Gotland and Latvia. In the deep of these basins the temperature variations are smaller. At the bottom of the Bornholm Basin, deeper than 80 m (260 ft), the temperature typically is 1–10 °C (34–50 °F), and at the bottom of the Gotland Basin, at depths greater than 225 m (738 ft), the temperature typically is 4–7 °C (39–45 °F).[39]Generally, offshore locations, lower latitudes and islands maintainmaritime climates,but adjacent to the watercontinental climatesare common, especially on theGulf of Finland.In the northern tributaries the climates transition from moderate continental tosubarcticon the northernmost coastlines.

On the long-term average, the Baltic Sea is ice-covered at the annual maximum for about 45% of its surface area. The ice-covered area during such a typical winter includes theGulf of Bothnia,theGulf of Finland,theGulf of Riga,the archipelago west of Estonia, theStockholm archipelago,and theArchipelago Seasouthwest of Finland. The remainder of the Baltic does not freeze during a normal winter, except sheltered bays and shallow lagoons such as theCuronian Lagoon.The ice reaches its maximum extent in February or March; typical ice thickness in the northernmost areas in theBothnian Bay,the northern basin of the Gulf of Bothnia, is about 70 cm (28 in) for landfast sea ice. The thickness decreases farther south.

Freezing begins in the northern extremities of the Gulf of Bothnia typically in the middle of November, reaching the open waters of the Bothnian Bay in early January. TheBothnian Sea,the basin south ofKvarken,freezes on average in late February. The Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Riga freeze typically in late January. In 2011, the Gulf of Finland was completely frozen on 15 February.[40]

The ice extent depends on whether the winter is mild, moderate, or severe. In severe winters ice can form around southernSwedenand even in theDanish straits.According to the 18th-century natural historianWilliam Derham,during the severe winters of 1703 and 1708, the ice cover reached as far as the Danish straits.[41]Frequently, parts of the Gulf of Bothnia and the Gulf of Finland are frozen, in addition to coastal fringes in more southerly locations such as the Gulf of Riga. This description meant that the whole of the Baltic Sea was covered with ice.

Since 1720, the Baltic Sea has frozen over entirely 20 times, most recently in early 1987, which was the most severe winter in Scandinavia since 1720. The ice then covered 400,000 km2(150,000 sq mi). During the winter of 2010–11, which was quite severe compared to those of the last decades, the maximum ice cover was 315,000 km2(122,000 sq mi), which was reached on 25 February 2011. The ice then extended from the north down to the northern tip ofGotland,with small ice-free areas on either side, and the east coast of the Baltic Sea was covered by an ice sheet about 25 to 100 km (16 to 62 mi) wide all the way toGdańsk.This was brought about by a stagnanthigh-pressure areathat lingered over central and northern Scandinavia from around 10 to 24 February. After this, strong southern winds pushed the ice further into the north, and much of the waters north of Gotland were again free of ice, which had then packed against the shores of southern Finland.[42]The effects of the afore-mentioned high-pressure area did not reach the southern parts of the Baltic Sea, and thus the entire sea did not freeze over. However, floating ice was additionally observed nearŚwinoujścieharbor in January 2010.

In recent years before 2011, the Bothnian Bay and the Bothnian Sea were frozen with solid ice near the Baltic coast and dense floating ice far from it. In 2008, almost no ice formed except for a short period in March.[43]

During winter,fast ice,which is attached to the shoreline, develops first, rendering ports unusable without the services oficebreakers.Level ice,ice sludge,pancake ice,andrafter iceform in the more open regions. The gleaming expanse of ice is similar to theArctic,with wind-driven pack ice and ridges up to 15 m (49 ft). Offshore of the landfast ice, the ice remains very dynamic all year, and it is relatively easily moved around by winds and therefore formspack ice,made up of large piles and ridges pushed against the landfast ice and shores.

In spring, the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Bothnia normally thaw in late April, with some ice ridges persisting until May in the eastern extremities of the Gulf of Finland. In the northernmost reaches of the Bothnian Bay, ice usually stays until late May; by early June it is practically always gone. However, in the famine year of1867remnants of ice were observed as late as 17 July nearUddskär.[44]Even as far south asØresund,remnants of ice have been observed in May on several occasions; nearTaarbaekon 15 May 1942 and near Copenhagen on 11 May 1771. Drift ice was also observed on 11 May 1799.[45][46][47]

The ice cover is the main habitat for two large mammals, thegrey seal(Halichoerus grypus) and the Balticringed seal(Pusa hispida botnica), both of which feed underneath the ice and breed on its surface. Of these two seals, only the Baltic ringed seal suffers when there is not adequate ice in the Baltic Sea, as it feeds its young only while on ice. The grey seal is adapted to reproducing also with no ice in the sea. The sea ice also harbors several species of algae that live in the bottom and inside unfrozen brine pockets in the ice.

Due to the often fluctuating winter temperatures between above and below freezing, the saltwater ice of the Baltic Sea can be treacherous and hazardous to walk on, in particular in comparison to the more stable fresh water-ice sheets in the interior lakes.

Hydrography

editThe Baltic Sea flows out through theDanish straits;however, the flow is complex. A surface layer of brackish water discharges 940 km3(230 cu mi) per year into theNorth Sea.Due to the difference insalinity,by salinity permeation principle, a sub-surface layer of more saline water moving in the opposite direction brings in 475 km3(114 cu mi) per year. It mixes very slowly with the upper waters, resulting in a salinity gradient from top to bottom, with most of the saltwater remaining below 40 to 70 m (130 to 230 ft) deep. The general circulation is anti-clockwise: northwards along its eastern boundary, and south along with the western one.[48]

The difference between the outflow and the inflow comes entirely from freshwater.More than 250 streams drain a basin of about 1,600,000 km2(620,000 sq mi), contributing a volume of 660 km3(160 cu mi) per year to the Baltic. They include the major rivers of north Europe, such as theOder,theVistula,theNeman,theDaugavaand theNeva.Additional fresh water comes from the difference ofprecipitationless evaporation, which is positive.

An important source of salty water is infrequent inflows (also known asmajor Baltic inflowsor MBIs) ofNorth Seawater into the Baltic. Such inflows, important to the Baltic ecosystem because of the oxygen they transport into the Baltic deeps, happen on average once per year, but large pulses that can replace the anoxic deep water in theGotland Deepoccur about once in ten years. Previously, it was believed that the frequency of MBIs had declined since 1980, but recent studies have challenged this view and no longer display a clear change in the frequency or intensity of saline inflows. Instead, a decadal variability in the intensities of MBIs is observed with a main period of approximately 30 years.[49][50]

The water level is generally far more dependent on the regional wind situation than on tidal effects. However, tidal currents occur in narrow passages in the western parts of the Baltic Sea. Tides can reach 17 to 19 cm (6.7 to 7.5 in) in the Gulf of Finland.[51]

Thesignificant wave heightis generally much lower than that of theNorth Sea.Quite violent, sudden storms sweep the surface ten or more times a year, due to large transient temperature differences and a long reach of the wind. Seasonal winds also cause small changes in sea level, of the order of 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in).[48]According to the media, during a storm in January 2017, an extreme wave above 14 m (46 ft) has been measured and significant wave height of around 8 m (26 ft) has been measured by theFMI.A numerical study has shown the presence of events with 8 to 10 m (26 to 33 ft) significant wave heights. Those extreme waves events can play an important role in the coastal zone on erosion and sea dynamics.[52]

Salinity

editThe Baltic Sea is the world's largest inlandbrackishsea.[53]Only twoother brackish watersare larger according to some measurements: TheBlack Seais larger in both surface area and water volume, but most of it is located outside thecontinental shelf(only a small fraction is inland). TheCaspian Seais larger in water volume, but—despite its name—it is a lake rather than a sea.[53]

The Baltic Sea'ssalinityis much lower than that of ocean water (which averages 3.5%), as a result of abundant freshwater runoff from the surrounding land (rivers, streams and alike), combined with the shallowness of the sea itself; runoff contributes roughly one-fortieth its total volume per year, as the volume of the basin is about 21,000 km3(5,000 cu mi) and yearly runoff is about 500 km3(120 cu mi).[citation needed]

The open surface waters of the Baltic Sea "proper" generally have a salinity of 0.3 to 0.9%, which is border-linefreshwater.The flow of freshwater into the sea from approximately two hundred rivers and the introduction of salt from the southwest builds up a gradient of salinity in the Baltic Sea. The highest surface salinities, generally 0.7–0.9%, are in the southwesternmost part of the Baltic, in the Arkona and Bornholm basins (the former located roughly between southeastZealandand Bornholm, and the latter directly east of Bornholm). It gradually falls further east and north, reaching the lowest in theBothnian Bayat around 0.3%.[54]Drinking the surface water of the Baltic as a means of survival would actually hydrate the body instead ofdehydrating,as is the case with ocean water.[note 1][citation needed]

As saltwater is denser than freshwater, the bottom of the Baltic Sea is saltier than the surface. This creates a vertical stratification of the water column, ahalocline,that represents a barrier to the exchange ofoxygenand nutrients, and fosters completely separate maritime environments.[55]The difference between the bottom and surface salinities varies depending on location. Overall it follows the same southwest to east and north pattern as the surface. At the bottom of the Arkona Basin (equalling depths greater than 40 m or 130 ft) and Bornholm Basin (depths greater than 80 m or 260 ft) it is typically 1.4–1.8%. Further east and north the salinity at the bottom is consistently lower, being the lowest in Bothnian Bay (depths greater than 120 m or 390 ft) where it is slightly below 0.4%, or only marginally higher than the surface in the same region.[54]

In contrast, the salinity of theDanish straits,which connect the Baltic Sea and Kattegat, tends to be significantly higher, but with major variations from year to year. For example, the surface and bottom salinity in theGreat Beltis typically around 2.0% and 2.8% respectively, which is only somewhat below that of the Kattegat.[54]The water surplus caused by the continuous inflow of rivers and streams to the Baltic Sea means that there generally is a flow of brackish water out through the Danish straits to the Kattegat (and eventually the Atlantic).[56]Significant flows in the opposite direction, salt water from the Kattegat through the Danish straits to the Baltic Sea, are less regular and are known asmajor Baltic inflows (MBIs).

Major tributaries

editThe rating ofmean dischargesdiffers from the ranking of hydrological lengths (from the most distant source to the sea) and the rating of the nominal lengths.Göta älv,a tributary of theKattegat,is not listed, as due to the northward upper low-salinity-flow in the sea, its water hardly reaches the Baltic proper:

| Name | Mean discharge (m3/s) |

Length (km) | Basin (km2) | States sharing the basin | Longest watercourse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neva | 2500 | 74 (nominal) 860 (hydrological) |

281,000 | Russia,Finland(Ladoga-affluentVuoksi) | Suna(280 km) →Lake Onega(160 km) → Svir(224 km) →Lake Ladoga(122 km) → Neva |

| Vistula | 1080 | 1047 | 194,424 | Poland,tributaries:Belarus,Ukraine,Slovakia | Bug(774 km) →Narew(22 km) → Vistula (156 km) total 1204 km |

| Daugava | 678 | 1020 | 87,900 | Russia(source),Belarus,Latvia | |

| Neman | 678 | 937 | 98,200 | Belarus(source),Lithuania,Russia | |

| Kemijoki | 556 | 550 (main river) 600 (river system) |

51,127 | Finland,Norway(source ofOunasjoki) | longer tributaryKitinen |

| Oder | 540 | 866 | 118,861 | Czech Republic(source),Poland,Germany | Warta(808 km) → Oder (180 km) total: 928 km |

| Lule älv | 506 | 461 | 25,240 | Sweden | |

| Narva | 415 | 77 (nominal) 652 (hydrological) |

56,200 | Russia(source of Velikaya),Estonia | Velikaya(430 km) →Lake Peipus(145 km) → Narva |

| Torne älv | 388 | 520 (nominal) 630 (hydrological) |

40,131 | Norway(source),Sweden,Finland | Válfojohka → Kamajåkka → Abiskojaure →Abiskojokk (total 40 km) →Torneträsk(70 km) → Torne älv |

Islands and archipelagoes

edit- Åland(Finland,autonomous)

- Archipelago Sea(Finland)

- Blekinge archipelago(Sweden)

- Bornholm,includingChristiansø(Denmark)

- Falster(Denmark)

- Gotland(Sweden)

- Hailuoto(Finland)

- Kotlin(Russia)

- Lolland(Denmark)

- Kvarkenarchipelago, includingValsörarna(Finland)

- Møn(Denmark)

- Öland(Sweden)

- Rügen(Germany)

- Stockholm archipelago(Sweden)

- Usedomor Uznam (split betweenGermanyandPoland)

- West Estonian archipelago(Estonia):

- Wolin(Poland)

- Zealand(Denmark)

Coastal countries

editCountries that border the sea: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden.

Countries lands in the outerdrainage basin:Belarus, Czech Republic, Norway, Slovakia, Ukraine.

The Baltic Sea drainage basin is roughly four times the surface area of the sea itself. About 48% of the region is forested, with Sweden and Finland containing the majority of the forest, especially around the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland.

About 20% of the land is used for agriculture and pasture, mainly in Poland and around the edge of the Baltic Proper, in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. About 17% of the basin is unused open land with another 8% of wetlands. Most of the latter are in the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland.

The rest of the land is heavily populated. About 85 million people live in the Baltic drainage basin, 15 million within 10 km (6 mi) of the coast and 29 million within 50 km (31 mi) of the coast. Around 22 million live in population centers of over 250,000. 90% of these are concentrated in the 10 km (6 mi) band around the coast. Of the nations containing all or part of the basin, Poland includes 45% of the 85 million, Russia 12%, Sweden 10% and the others less than 6% each.[57]

Cities

editThe biggest coastal cities (by population):

- Saint Petersburg(Russia) 5,392,992 (metropolitan area 6,000,000)

- Stockholm(Sweden) 962,154 (metropolitan area 2,315,612)

- Helsinki(Finland) 665,558 (metropolitan area 1,559,558)

- Riga(Latvia) 614,618 (metropolitan area 1,070,00)

- Gdańsk(Poland) 462,700 (metropolitan area1,041,000)

- Tallinn(Estonia) 458,398 (metropolitan area 542,983)

- Kaliningrad(Russia) 431,500

- Szczecin(Poland) 413,600 (metropolitan area 778,000)

- Espoo(Finland) 306,792 (part of Helsinki metropolitan area)

- Gdynia(Poland) 255,600 (metropolitan area1,041,000)

- Kiel(Germany) 247,000[58]

- Lübeck(Germany) 216,100

- Rostock(Germany) 212,700

- Klaipėda(Lithuania) 194,400

- Oulu(Finland) 191,050

- Turku(Finland) 180,350

Other important ports:

- Estonia:

- Finland:

- Germany:

- Flensburg94,000

- Stralsund58,000

- Greifswald55,000

- Wismar44,000

- Eckernförde22,000

- Neustadt in Holstein16,000

- Wolgast12,000

- Sassnitz10,000

- Latvia:

- Lithuania:

- Palanga17,000

- Poland:

- Kołobrzeg44,800

- Świnoujście41,500

- Police34,284

- Władysławowo15,000

- Darłowo14,000

- Russia:

- Sweden:

- Norrköping84,000

- Gävle75,451

- Trelleborg26,000

- Karlshamn19,000

- Oxelösund11,000

Geology

editThe Baltic Sea somewhat resembles ariverbed,with two tributaries, theGulf of FinlandandGulf of Bothnia.Geologicalsurveys show that before thePleistocene,instead of the Baltic Sea, there was a wide plain around a great river that paleontologists call theEridanos.Several Pleistoceneglacialepisodes scooped out the river bed into the sea basin. By the time of the last, orEemian Stage(MIS5e), the Eemian Sea was in place. Instead of a true sea, the Baltic can even today also be understood as the commonestuaryof all rivers flowing into it.

From that time the waters underwent a geologic history summarized under the names listed below. Many of the stages are named after marine animals (e.g. theLittorinamollusk) that are clear markers of changing water temperatures and salinity.

The factors that determined the sea's characteristics were the submergence or emergence of the region due to the weight of ice and subsequent isostatic readjustment, and the connecting channels it found to theNorth Sea-Atlantic,either through the straits ofDenmarkor at what are now the large lakes ofSweden,and theWhite Sea-Arctic Sea.

- Eemian Sea,130,000–115,000 (years ago)

- Baltic Ice Lake,12,600–10,300

- Yoldia Sea,10,300–9500

- Ancylus Lake,9,500–8,000

- Mastogloia Sea,8,000–7,500

- Littorina Sea,7,500–4,000

- Post-Littorina Sea, 4,000–present

The land is still emergingisostaticallyfrom its depressed state, which was caused by the weight of ice during the last glaciation. The phenomenon is known aspost-glacial rebound.Consequently, the surface area and the depth of the sea are diminishing. The uplift is about eight millimeters per year on the Finnish coast of the northernmost Gulf of Bothnia. In the area, the former seabed is only gently sloping, leading to large areas of land being reclaimed in what are, geologically speaking, relatively short periods (decades and centuries).

The "Baltic Sea anomaly"

editThe "Baltic Sea anomaly" is a feature on an indistinctsonarimage taken by Swedish salvage divers on the floor of the northern Baltic Sea in June 2011. The treasure hunters suggested the image showed an object with unusual features of seemingly extraordinary origin. Speculation published intabloid newspapersclaimed that the object was a sunkenUFO.A consensus of experts and scientists say that the image most likely shows a naturalgeological formation.[59][60][61][62][63]

Biology

editFauna and flora

editThe fauna of the Baltic Sea is a mixture of marine and freshwater species. Among marine fishes areAtlantic cod,Atlantic herring,European hake,European plaice,European flounder,shorthorn sculpinandturbot,and examples of freshwater species includeEuropean perch,northern pike,whitefishandcommon roach.Freshwater species may occur at outflows of rivers or streams in all coastal sections of the Baltic Sea. Otherwise, marine species dominate in most sections of the Baltic, at least as far north asGävle,where less than one-tenth are freshwater species. Further north the pattern is inverted. In the Bothnian Bay, roughly two-thirds of the species are freshwater. In the far north of this bay, saltwater species are almost entirely absent.[39]For example, thecommon starfishandshore crab,two species that are very widespread along European coasts, are both unable to cope with the significantly lower salinity. Their range limit is west of Bornholm, meaning that they are absent from the vast majority of the Baltic Sea.[39]Some marine species, like the Atlantic cod and European flounder, can survive at relatively low salinities but need higher salinities to breed, which therefore occurs in deeper parts of the Baltic Sea.[64][65]The commonblue musselis the dominating animal species, and makes up more than 90% of the total animal biomass in the sea.[66]

There is a decrease in species richness from the Danish belts to theGulf of Bothnia.The decreasing salinity along this path causes restrictions in both physiology and habitats.[67]At more than 600 species of invertebrates, fish, aquatic mammals, aquatic birds andmacrophytes,the Arkona Basin (roughly between southeast Zealand and Bornholm) is far richer than other more eastern and northern basins in the Baltic Sea, which all have less than 400 species from these groups, with the exception of the Gulf of Finland with more than 750 species. However, even the most diverse sections of the Baltic Sea have far fewer species than the almost-full saltwater Kattegat, which is home to more than 1600 species from these groups.[39]The lack oftideshas affected the marine species as compared with the Atlantic.

Since the Baltic Sea is so young there are only two or three knownendemicspecies: the brown algaFucus radicansand the flounderPlatichthys solemdali.Both appear to have evolved in the Baltic basin and were only recognized as species in 2005 and 2018 respectively, having formerly been confused with more widespread relatives.[65][68]The tinyCopenhagen cockle(Parvicardium hauniense), a rare mussel, is sometimes considered endemic, but has now been recorded in the Mediterranean.[69]However, some consider non-Baltic records to be misidentifications of juvenilelagoon cockles(Cerastoderma glaucum).[70]Several widespread marine species have distinctive subpopulations in the Baltic Sea adapted to the low salinity, such as the Baltic Sea forms of the Atlantic herring andlumpsucker,which are smaller than the widespread forms in the North Atlantic.[56]

A peculiar feature of the fauna is that it contains a number of glacialrelict species,isolated populations of arctic species which have remained in the Baltic Sea since the lastglaciation,such as the large isopodSaduria entomon,the Baltic subspecies ofringed seal,and thefourhorn sculpin.Some of these relicts are derived fromglacial lakes,such asMonoporeia affinis,which is a main element in thebenthic faunaof the low-salinityBothnian Bay.

Cetaceansin the Baltic Sea are monitored by the countries bordering the sea and data compiled by various intergovernmental bodies, such asASCOBANS.A critically endangered population ofharbor porpoiseinhabit the Baltic proper, whereas the species is abundant in the outer Baltic (Western Baltic andDanish straits) and occasionally oceanic and out-of-range species such asminke whales,[71]bottlenose dolphins,[72]beluga whales,[73]orcas,[74]andbeaked whales[75]visit the waters. In recent years, very small, but with increasing rates,fin whales[76][77][78][79]andhumpback whalesmigrate into Baltic sea including mother and calf pair.[80]Now extinct Atlanticgrey whales(remains found fromGräsöalongBothnian Sea/southernBothnian Gulf[81]andYstad[82]) and eastern population ofNorth Atlantic right whalesthat is facingfunctional extinction[83]once migrated into Baltic Sea.[84]

Other notablemegafaunainclude thebasking sharks.[85]

Environmental status

editSatellite images taken in July 2010 revealed a massivealgal bloomcovering 377,000 square kilometres (146,000 sq mi) in the Baltic Sea. The area of the bloom extended from Germany and Poland to Finland. Researchers of the phenomenon have indicated that algal blooms have occurred every summer for decades. Fertilizer runoff from surrounding agricultural land has exacerbated the problem and led to increasedeutrophication.[86]

Approximately 100,000 km2(38,610 sq mi) of the Baltic's seafloor (a quarter of its total area) is a variabledead zone.The more saline (and therefore denser) water remains on the bottom, isolating it from surface waters and the atmosphere. This leads to decreased oxygen concentrations within the zone. It is mainly bacteria that grow in it, digesting organic material and releasing hydrogen sulfide. Because of this large anaerobic zone, the seafloor ecology differs from that of the neighboring Atlantic.

Plans to artificially oxygenate areas of the Baltic that have experienced eutrophication have been proposed by theUniversity of Gothenburgand Inocean AB. The proposal intends to use wind-driven pumps to pump oxygen-rich surface water to a depth of around 130 m.[87]

AfterWorld War II,Germany had to be disarmed and large quantities of ammunition stockpiles were disposed directly into the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. Environmental experts and marine biologists warn that these ammunition dumps pose an environmental threat with potentially life-threatening consequences to the health and safety of humans on the coastlines of these seas.[88]

Climate change,pollutionfrom agriculture and forestry, impose such strong effects on the ecosystems of the Baltic sea, that there is a concern the sea will turn from acarbon sinkto a source ofCO2andmethane.[89]

Economy

editConstruction of theGreat Belt Bridgein Denmark (completed 1997) and theØresund Bridge-Tunnel (completed 1999), linking Denmark with Sweden, provided a highway and railroad connection between Sweden and the Danish mainland (theJutland Peninsula,precisely theZealand). The undersea tunnel of the Øresund Bridge-Tunnel provides for navigation of large ships into and out of the Baltic Sea. The Baltic Sea is the main trade route for the export of Russian petroleum. Many of the countries neighboring the Baltic Sea have been concerned about this since a major oil leak in a seagoing tanker would be disastrous for the Baltic—given the slow exchange of water.[citation needed]The tourism industry surrounding the Baltic Sea is naturally concerned aboutoil pollution.[citation needed]

Much shipbuilding is carried out in the shipyards around the Baltic Sea. The largest shipyards are atGdańsk,Gdynia,andSzczecin,Poland;Kiel,Germany;KarlskronaandMalmö,Sweden;Rauma,Turku,andHelsinki,Finland;Riga,Ventspils,andLiepāja,Latvia;Klaipėda,Lithuania; andSaint Petersburg,Russia.

There are several cargo and passenger ferries that operate on the Baltic Sea, such asScandlines,Silja Line,Polferries,theViking Line,Tallink,andSuperfast Ferries.

Construction of theFehmarn Belt Fixed Linkbetween Denmark and Germany is due to finish in 2029. It will be a three-bore tunnel carrying four motorway lanes and two rail tracks.

Through the development ofoffshore wind powerthe Baltic Sea is expected to become a major source of energy for countries in the region. According to the Marienborg Declaration, signed in 2022, all EU Baltic Sea states have announced their intentions to have 19.6 gigawatts of offshore wind in operation by 2030.[90]

Tourism

edit|

Piers

|

Resort towns

|

The Helsinki Convention

edit1974 Convention

editFor the first time ever, all the sources of pollution around an entire sea were made subject to a single convention, signed in 1974 by the then seven Baltic coastal states. The 1974 Convention entered into force on 3 May 1980.

1992 Convention

editIn the light of political changes and developments in international environmental and maritime law, a new convention was signed in 1992 by all the states bordering on the Baltic Sea, and the European Community. After ratification, theConventionentered into force on 17 January 2000. The Convention covers the whole of the Baltic Sea area, including inland waters and the water of the sea itself, as well as the seabed. Measures are also taken in the whole catchment area of the Baltic Sea to reduce land-based pollution. The convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area, 1992, entered into force on 17 January 2000.

The governing body of the convention is theHelsinki Commission,[91]also known as HELCOM, or Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission. The present contracting parties are Denmark, Estonia, the European Community, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, and Sweden.

The ratification instruments were deposited by the European Community, Germany, Latvia and Sweden in 1994, by Estonia and Finland in 1995, by Denmark in 1996, by Lithuania in 1997, and by Poland and Russia in November 1999.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^A healthy serum concentration of sodium is around 0.8–0.85%, and healthy kidneys can concentrate salt in urine to at least 1.4%.

References

edit- ^"Coalition Clean Baltic".Archived fromthe originalon 2 June 2013.Retrieved5 July2013.

- ^Gunderson, Lance H.; Pritchard, Lowell (1 October 2002).Resilience and the Behavior of Large-Scale Systems.Island Press.ISBN9781559639712– via Google Books.

- ^Niktalab, Poopak(2024).Over the Alps: History of Children and Youth Literature in Europe(in Persian) (1st ed.). Tehran, Iran: Faradid Publisher. p. 6.ISBN9786225740457.

- ^"Text of Helsinki Convention".Archived fromthe originalon 2 May 2014.Retrieved26 April2014.

- ^"Sundzoll".Academic dictionaries and encyclopedias.Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2022.Retrieved16 June2022.

- ^"Fragen zum Meer (Antworten) – IOW".www.io-warnemuende.de.Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2014.Retrieved31 May2023.

- ^"Swedish Chemicals Agency (KEMI): The BaltSens Project – The sensitivity of the Baltic Sea ecosystems to hazardous compounds"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 May 2013.Retrieved26 April2014.

- ^Tacitus,Germania(online textArchived18 April 2003 at theWayback Machine):Ergo iam dextro Suebici maris litore Aestiorum gentes adluuntur, quibus ritus habitusque Sueborum, lingua Britannicae propior.– "Upon the right of the Suevian Sea the Æstyan nations reside, who use the same customs and attire with the Suevians; their language more resembles that of Britain." (English text onlineArchived1 December 2020 at theWayback Machine)

- ^Benario, Herbert W. (1 July 1999).Tacitus: Germania.Liverpool University Press. p. 110.ISBN978-1-80034-609-3.Archivedfrom the original on 13 May 2023.Retrieved13 May2023.

- ^Ptolemy,GeographyIII, chapter 5: "Sarmatia in Europe is bounded on the north by the Sarmatian ocean at the Venedic gulf" (online textArchived3 August 2017 at theWayback Machine).

- ^(in Swedish)BalteusArchived27 January 2021 at theWayback MachineinNordisk familjebok.

- ^"Indo-European etymology: Query result".25 February 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 25 February 2007.

- ^Schmitt 1989,pp. 310–313.

- ^Forbes, Nevill (1910).The Position of the Slavonic Languages at the present day.Oxford University Press.p. 7.

- ^Dini, Pietro Umberto (1997).Le lingue baltiche(in Italian). Florence: La Nuova Italia.ISBN978-88-221-2803-4.

- ^Cfr.Hartmann Schedel's 1493 (map), where the Baltic Sea is calledMare Germanicum,whereas the Northern Sea is calledOceanus Germanicus.

- ^TheOld English Orosius

- ^Portham, 1880, p61

- ^"Livones.net - Burājot lībiešu jūrā: debespušu nosaukumi lībiešu valodā".www.livones.net.Archivedfrom the original on 20 July 2023.Retrieved20 July2023.

- ^"A JOURNEY ALONG THE LIVONIAN COAST / REIZ PIDS LĪVÕD RANDÕ"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 20 July 2023.Retrieved20 July2023.

- ^"The History of Russian Amber, Part 1: The Beginning"Archived15 March 2018 at theWayback Machine,Leta.st

- ^Wend – West WendArchived22 October 2014 at theWayback Machine.Britannica. Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^Chemical Weapon Time Bomb Ticks in the Baltic SeaArchived24 January 2012 at theWayback MachineDeutsche Welle,1 February 2008.

- ^Activities 2006: OverviewArchived14 January 2009 at theWayback MachineBaltic Sea Environment Proceedings No. 112.Helsinki Commission.

- ^Ellis, M.G.M.W. (1986). "Sweden's Ghosts?".Proceedings.112(3).United States Naval Institute:95–101.

- ^Kirby, Paul (4 April 2023)."Nato's border with Russia doubles as Finland joins".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2023.Retrieved5 April2023.

- ^abMilne, Richard; Seddon, Max (7 March 2024)."Sweden joins 'Nato lake' on Moscow's doorstep".Financial Times.Retrieved7 March2024.

- ^"Does Sweden joining make the Baltic Sea a 'NATO lake'?".RFI.26 February 2024.Retrieved29 April2024.

- ^"No longer neutral waters: What Baltic Sea strategy for Sweden after NATO enlargement?".France 24.28 March 2024.Retrieved29 April2024.

- ^Kayali, Laura (13 July 2023)."Sorry Russia, the Baltic Sea is NATO's lake now".POLITICO.Retrieved29 April2024.

- ^Sztobryn, Marzenna; Stigge, Hans-Joachim; Wielbińska, Danuta; Weidig, Bärbel; Stanisławczyk, Ida; Kańska, Alicja; Krzysztofik, Katarzyna; Kowalska, Beata; Letkiewicz, Beata; Mykita, Monika (2005)."Sturmfluten in der südlichen Ostsee (Westlicher und mittlerer Teil)"[Storm floods in the Southern Baltic (western and central part)](PDF).Berichte des Bundesamtes für Seeschifffahrt und Hydrographie(in German) (39): 6. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 October 2012.Retrieved2 July2012.

- ^"Sturmfluten an der Ostseeküste – eine vergessene Gefahr?"[Storm floods along the Baltic Sea coastline – a forgotten threat?].Informations-, Lern-, und Lehrmodule zu den Themen Küste, Meer und Integriertes Küstenzonenmanagement.EUCC Die Küsten Union Deutschland e. V. Archived fromthe originalon 24 July 2014.Retrieved2 July2012.CitingWeiss, D. "Schutz der Ostseeküste von Mecklenburg-Vorpommern". In Kramer, J.; Rohde, H. (eds.).Historischer Küstenschutz: Deichbau, Inselschutz und Binnenentwässerung an Nord- und Ostsee[Historical coastal protection: construction of dikes, insular protection and inland drainage at North Sea and Baltic Sea] (in German). Stuttgart: Wittwer. pp. 536–567.

- ^Tiesel, Reiner (October 2003)."Sturmfluten an der deutschen Ostseeküste"[Storm floods at the German Baltic Sea coasts].Informations-, Lern-, und Lehrmodule zu den Themen Küste, Meer und Integriertes Küstenzonenmanagement(in German). EUCC Die Küsten Union Deutschland e. V. Archived fromthe originalon 12 October 2012.Retrieved2 July2012.

- ^"EuroOcean".Archived fromthe originalon 15 April 2014.Retrieved14 April2014.

- ^"Geography of the Baltic Sea Area".Archived fromthe originalon 21 April 2006.Retrieved27 August2005.at envir.ee. (archived) (21 April 2006). Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^"p. 7"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 8 December 2015.Retrieved27 November2015.

- ^"Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition"(PDF).International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 8 October 2011.Retrieved28 December2020.

- ^"Baltic Sea area clickable map".www.baltic.vtt.fi.Archived fromthe originalon 23 October 2007.Retrieved11 April2008.

- ^abcde"Our Baltic Sea".HELCOM.Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2018.Retrieved27 July2018.

- ^Helsingin Sanomat,16 February 2011, p. A8.

- ^Derham, WilliamPhysico-Theology: Or, A Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God from His Works of Creation(London, 1713).

- ^Helsingin Sanomat,10 February 2011, p. A4; 25 February 2011, p. A5; 11 June 2011, p. A12.

- ^Sea Ice SurveyArchived25 November 2016 at theWayback MachineSpace Science and Engineering Center, University of Wisconsin.

- ^"Nödåret 1867".Byar i Luleå. Archived fromthe originalon 27 July 2011.

- ^"Isvintrene i 40'erne".TV 2. 19 January 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2017.Retrieved6 January2017.

- ^"1771 – Nationalmuseet".Archived fromthe originalon 16 April 2017.Retrieved15 April2017.

- ^"Is i de danske farvande i 1700-tallet".Nationalmuseet.Archivedfrom the original on 18 February 2018.Retrieved18 February2018.

- ^abAlhonen, p. 88

- ^Mohrholz, Volker (2018)."Major Baltic Inflow Statistics – Revised".Frontiers in Marine Science.5.doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00384.ISSN2296-7745.

- ^Lehmann, Andreas; Myrberg, Kai; Post, Piia; Chubarenko, Irina; Dailidiene, Inga; Hinrichsen, Hans-Harald; Hüssy, Karin; Liblik, Taavi; Meier, H. E. Markus; Lips, Urmas; Bukanova, Tatiana (16 February 2022)."Salinity dynamics of the Baltic Sea".Earth System Dynamics.13(1): 373–392.Bibcode:2022ESD....13..373L.doi:10.5194/esd-13-373-2022.ISSN2190-4979.Archivedfrom the original on 21 July 2023.Retrieved24 July2023.

- ^Medvedev, I. P.; Rabinovich, A. B.; Kulikov, E. A. (September 2013)."Tidal oscillations in the Baltic Sea".Oceanology.53(5): 526–538.Bibcode:2013Ocgy...53..526M.doi:10.1134/S0001437013050123.ISSN0001-4370.S2CID129778127.Archivedfrom the original on 4 December 2022.Retrieved27 September2021.

- ^Rutgersson, Anna; Kjellström, Erik; Haapala, Jari; Stendel, Martin; Danilovich, Irina; Drews, Martin; Jylhä, Kirsti; Kujala, Pentti; Guo Larsén, Xiaoli; Halsnæs, Kirsten; Lehtonen, Ilari (6 April 2021)."Natural Hazards and Extreme Events in the Baltic Sea region".Earth System Dynamics Discussions.13(1): 251–301.doi:10.5194/esd-2021-13.ISSN2190-4979.S2CID233556209.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2021.Retrieved29 September2021.

- ^abSnoeijs-Leijonmalm P.; E.Andrén (2017). "Why is the Baltic Sea so special to live in?". In P. Snoeijs-Leijonmalm; H. Schubert; T. Radziejewska (eds.).Biological Oceanography of the Baltic Sea.Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 23–84.ISBN978-94-007-0667-5.

- ^abcViktorsson, L. (16 April 2018)."Hydrogeography and oxygen in the deep basins".HELCOM.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2018.Retrieved27 July2018.

- ^"The Baltic Sea: Its Past, Present and Future"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 June 2007.(352 KB),Jan Thulin and Andris Andrushaitis, Religion, Science and the Environment Symposium V on the Baltic Sea (2003).

- ^abMuus, B.; J.G. Nielsen; P. Dahlstrom; B. Nystrom (1999).Sea Fish.Scandinavian Fishing Year Book.ISBN978-8790787004.

- ^Sweitzer, J (May 2019)."Land Use and Population Density in the Baltic Sea Drainage Basin: A GIS Database".Ambio.25:20.Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2020.Retrieved11 July2019– via Researchgate.

- ^Statistische KurzinformationArchived11 November 2012 at theWayback Machine(in German). Landeshauptstadt Kiel. Amt für Kommunikation, Standortmarketing und Wirtschaftsfragen Abteilung Statistik. Retrieved on 11 October 2012.

- ^Mikkelson, David (9 January 2015)."UFO at the Bottom of the Baltic Sea? Rumor: Photograph shows a UFO discovered at the bottom of the Baltic Sea".Urban Legends Reference Pages© 1995-2017 by Snopes.com.Snopes.com.Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2020.Retrieved1 August2017.

- ^Kershner, Kate (7 April 2015)."What is the Baltic Sea anomaly?".How Stuff Works.HowStuffWorks, a division ofInfoSpace Holdings LLC.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2017.Retrieved1 August2017.

- ^Wolchover, Natalie (30 August 2012)."Mysterious' Baltic Sea Object Is a Glacial Deposit".Live Science.Live Science, Purch.Archivedfrom the original on 2 August 2017.Retrieved1 August2017.

- ^Main, Douglas (2 January 2012)."Underwater UFO? Get Real, Experts Say".Popular Mechanics.Archivedfrom the original on 28 December 2014.Retrieved14 March2018.

- ^Interview of Finnish planetary geomorphologist Jarmo Korteniemi (at 1:10:45) onMars Moon Space Tv (30 January 2017),Baltic Sea Anomaly. The Unsolved Mystery. Part 1-2,archivedfrom the original on 23 November 2021,retrieved14 March2018

- ^Nissling, L.; A. Westin (1997)."Salinity requirements for successful spawning of Baltic and Belt Sea cod and the potential for cod stock interactions in the Baltic Sea".Marine Ecology Progress Series.152(1/3): 261–271.Bibcode:1997MEPS..152..261N.doi:10.3354/meps152261.

- ^abMomigliano, M.; G.P.J. Denys; H. Jokinen; J. Merilä (2018)."Platichthys solemdali sp. nov. (Actinopterygii, Pleuronectiformes): A New Flounder Species From the Baltic Sea".Front. Mar. Sci.5(225).doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00225.

- ^Rydén, Lars; Migula, Pawel; Andersson, Magnus (11 January 2024).Environmental Science: Understanding, Protecting and Managing the Environment in the Baltic Sea Region.Baltic University Press.ISBN978-91-970017-0-0.Archivedfrom the original on 15 October 2023.Retrieved24 September2023.

- ^Lockwood, A. P. M.; Sheader, M.; Williams, J. A. (1998). "Life in Estuaries, Salt Marshes, Lagoons and Coastal Waters". In Summerhayes, C. P.; Thorpe, S. A. (eds.).Oceanography: An Illustrated Guide(2nd ed.). London: Manson Publishing. p. 246.ISBN978-1-874545-37-8.

- ^Pereyra, R.T.; L. Bergström; L. Kautsky; K. Johannesson (2009)."Rapid speciation in a newly opened postglacial marine environment, the Baltic Sea".BMC Evolutionary Biology.9(70): 70.Bibcode:2009BMCEE...9...70P.doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-70.PMC2674422.PMID19335884.

- ^Red List Benthic Invertebrate Expert Group (2013)Parvicardium hauniense.HELCOM. Accessed 27 July 2018.

- ^"Parvicardium hauniense".National Museum Wales. 17 May 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2018.Retrieved27 July2018.

- ^Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata)Archived30 October 2016 at theWayback Machine– MarLIN, The Marine Life Information Network

- ^"Baltic dolphin sightings confirmed".Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2019.Retrieved18 November2015.

- ^About the belugaArchived31 October 2016 at theWayback Machine– Russian Geographical Society

- ^Reeves, R.; Pitman, R.L.; Ford, J.K.B. (2017)."Orcinus orca".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2017:e.T15421A50368125.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15421A50368125.en.Retrieved12 November2021.

- ^"Rare Sowerby's beaked whale spotted in the Baltic Sea".Archivedfrom the original on 19 November 2015.Retrieved18 November2015.

- ^"Wieder Finnwal in der Ostsee".Archived fromthe originalon 15 April 2016.

- ^KG, Ostsee-Zeitung GmbH & Co."Finnwal in der Ostsee gesichtet".www.ostsee-zeitung.de.Archived fromthe originalon 30 October 2016.Retrieved30 October2016.

- ^Allgemeine, Augsburger."Angler filmt Wal in Ostsee-Bucht".Archivedfrom the original on 30 October 2016.Retrieved30 October2016.

- ^Jansson N.. 2007."Vi såg valen i viken"Archived7 September 2017 at theWayback Machine.Aftonbladet.Retrieved on 7 September 2017.

- ^"Whales seen again in the waters of the Baltic Sea".Science in Poland.Archivedfrom the original on 4 July 2022.Retrieved30 June2022.

- ^Jones L.M..Swartz L.S.. Leatherwood S..The Gray Whale: Eschrichtius RobustusArchived27 December 2022 at theWayback Machine."Eastern Atlantic Specimens". pp. 41–44.Academic Press.Retrieved on 5 September 2017

- ^Global Biodiversity Information Facility.Occurrence Detail 1322462463Archived6 November 2018 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved on 21 September 2017

- ^Berry, George."North Atlantic right whale".Archivedfrom the original on 25 May 2022.Retrieved16 June2022.

- ^"Regional Species Extinctions – Examples of regional species extinctions over the last 1000 years and more"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 25 April 2011.

- ^"Archived copy"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 7 August 2019.Retrieved18 November2015.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^"Satellite spies vast algal bloom in Baltic Sea".BBC News.23 July 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2010.Retrieved27 July2010.

- ^"Oxygenation at a Depth of 120 Meters Could Save the Baltic Sea, Researchers Demonstrate".Science Daily.Archivedfrom the original on 20 October 2017.Retrieved9 March2018.

- ^"Ticking time bombs on the bottom of the North and Baltic Sea".DW.COM.23 August 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 4 June 2020.Retrieved13 September2019.

- ^Korkman, Anna."Warming Baltic Sea: a red flag for global oceans".Phys.org.Retrieved19 July2024.

- ^Trakimavicius, Lukas."A Sea of Change: Energy Security in the Baltic region".EurActiv.Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2023.Retrieved26 July2023.

- ^Helcom: WelcomeArchived6 May 2007 at theWayback Machine.Helcom.fi. Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

Bibliography

edit- Alhonen, Pentti (1966). "Baltic Sea". In Fairbridge, Rhodes (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Oceanography.New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. pp. 87–91.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (1989). "BLACK SEA".Black Sea – Encyclopaedia Iranica.Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 3.pp. 310–313.

Further reading

edit- Norbert Götz. "Spatial Politics and Fuzzy Regionalism: The Case of the Baltic Sea Area."Baltic Worlds9 (2016) 3: 54–67.

- Aarno Voipio (ed., 1981): "The Baltic Sea." Elsevier Oceanography Series, vol. 30, Elsevier Scientific Publishing, 418 p,ISBN0-444-41884-9

- Ojaveer, H.; Jaanus, A.; MacKenzie, B. R.; Martin, G.; Olenin, S.; et al. (2010)."Status of Biodiversity in the Baltic Sea".PLoS ONE.5(9): e12467.Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512467O.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012467.PMC2931693.PMID20824189.

- Peter, Bruce (2009).Baltic Ferries.Ramsey, Isle of Man: Ferry Publications.ISBN9781906608057.

- The BACC II Author Team; et al. (2015).Second Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin.Regional Climate Studies. Springer.doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16006-1.ISBN978-3-319-16006-1.S2CID127011711.

Historical

edit- Bogucka, Maria. "The Role of Baltic Trade in European Development from the XVIth to the XVIIIth Centuries".Journal of European Economic History9 (1980): 5–20.

- Davey, James.The Transformation of British Naval Strategy: Seapower and Supply in Northern Europe, 1808–1812(Boydell, 2012).

- Dickson, Henry Newton(1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 3 (11th ed.). pp. 286–287.

- Fedorowicz, Jan K.England's Baltic Trade in the Early Seventeenth Century: A Study in Anglo-Polish Commercial Diplomacy(Cambridge UP, 2008).

- Frost, Robert I.The Northern Wars: War, State, and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558–1721(Longman, 2000).

- Grainger, John D.The British Navy in the Baltic(Boydell, 2014).

- Kent, Heinz S. K.War and Trade in Northern Seas: Anglo-Scandinavian Economic Relations in the Mid Eighteenth Century(Cambridge UP, 1973).

- Koningsbrugge, Hans van. "In War and Peace: The Dutch and the Baltic in Early Modern Times".Tijdschrift voor Skandinavistiek16 (1995): 189–200.

- Lindblad, Jan Thomas. "Structural Change in the Dutch Trade in the Baltic in the Eighteenth Century".Scandinavian Economic History Review33 (1985): 193–207.

- Lisk, Jill.The Struggle for Supremacy in the Baltic, 1600–1725(U of London Press, 1967).

- Niktalab, Poopak(2024).Over the Alps: History of Children and Youth literature in Europe (Chapter 2 Baltic sails: the evolution of children's and youth literature in the Baltic countries)(in Persian) (1st ed.). Tehran, Iran: Faradid Publisher. pp. 85–124.ISBN9786225740457.

- Roberts, Michael.The Early Vasas: A History of Sweden, 1523–1611(Cambridge UP, 1968).

- Rystad, Göran, Klaus-R. Böhme, and Wilhelm M. Carlgren, eds.In Quest of Trade and Security: The Baltic in Power Politics, 1500–1990.Vol. 1, 1500–1890. Stockholm: Probus, 1994.

- Salmon, Patrick, and Tony Barrow, eds.Britain and the Baltic: Studies in Commercial, Political and Cultural Relations(Sunderland University Press, 2003).

- Stiles, Andrina.Sweden and the Baltic 1523–1721(1992).

- Thomson, Erik. "Beyond the Military State: Sweden's Great Power Period in Recent Historiography".History Compass9 (2011): 269–283.doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00761.x

- Tielhof, Milja van. The "Mother of All Trades": The Baltic Grain Trade in Amsterdam from the Late 16th to Early 19th Century. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

- Warner, Richard. "British Merchants and Russian Men-of-War: The Rise of the Russian Baltic Fleet". In Peter the Great and the West: New Perspectives. Edited by Lindsey Hughes, 105–117. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

External links

edit- The Baltic Sea, Kattegat and Skagerrak – sea areas and draining basins, poster with integral information by the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute

- Baltic Sea clickable map and details.

- Protect the Baltic Sea while it's still not too late.

- The Baltic Sea Portal– a site maintained by the"Finnish Institute of Marine Research".Archived fromthe originalon 14 February 2008.Retrieved15 July2007.(FIMR) (in English, Finnish, Swedish and Estonian)

- www.balticnest.org

- Encyclopedia of Baltic History

- Old shipwrecksin the Baltic

- How the Baltic Sea was changing– Prehistory of the Baltic from thePolish Geological Institute

- Late Weichselian and Holocene shore displacement history of the Baltic Sea in Finland– more prehistory of the Baltic from theDepartment of Geographyof theUniversity of Helsinki

- Baltic Environmental Atlas: Interactive map of the Baltic Sea region

- Can a New Cleanup Plan Save the Sea? –spiegel.de

- List of all ferry lines in the Baltic Sea

- The Helsinki Commission (HELCOM)HELCOM is the governing body of the "Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area"

- Baltice.org– information related to winter navigation in the Baltic Sea.

- Baltic Sea Wind– Marine weather forecasts

- Ostseeflug– A short film (55'), showing the coastline and the major German cities at the Baltic sea.