Beautyis commonly described as a feature of objects that makes thempleasurableto perceive. Such objects include landscapes, sunsets, humans and works of art. Beauty, art and taste are the main subjects ofaesthetics,one of the fields of study withinphilosophy.As a positive aesthetic value, it is contrasted withuglinessas its negative counterpart.

One difficulty in understanding beauty is that it has both objective and subjective aspects: it is seen as a property of things but also as depending on the emotional response of observers. Because of its subjective side, beauty is said to be "in the eye of the beholder".[2]It has been argued that the ability on the side of the subject needed to perceive and judge beauty, sometimes referred to as the "sense of taste", can be trained and that the verdicts of experts coincide in the long run. This suggests the standards of validity of judgments of beauty are intersubjective, i.e. dependent on a group of judges, rather than fully subjective or objective.

Conceptions of beauty aim to capture what is essential to all beautiful things.Classical conceptionsdefine beauty in terms of the relation between the beautiful object as a whole and its parts: the parts should stand in the right proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole.Hedonist conceptionssee a necessary connection between pleasure and beauty, e.g. that for an object to be beautiful is for it to cause disinterested pleasure. Other conceptions include defining beautiful objects in terms of their value, of a loving attitude toward them or of their function.

Overview

Beauty, together with art and taste, is the main subject ofaesthetics,one of the major branches of philosophy.[3][4]Beauty is usually categorized as an aesthetic property besides other properties, like grace, elegance or thesublime.[5][6][7]As a positive aesthetic value, beauty is contrasted withuglinessas its negative counterpart. Beauty is often listed as one of the three fundamental concepts of human understanding besidestruthandgoodness.[5][8][6]

Objectivists orrealistssee beauty as an objective or mind-independent feature of beautiful things, which is denied bysubjectivists.[3][9]The source of this debate is that judgments of beauty seem to be based on subjective grounds, namely our feelings, while claiming universal correctness at the same time.[10]This tension is sometimes referred to as the "antinomy of taste".[4]Adherents of both sides have suggested that a certain faculty, commonly called asense of taste,is necessary for making reliable judgments about beauty.[3][10]David Hume,for example, suggests that this faculty can be trained and that the verdicts of experts coincide in the long run.[3][9]

Beauty is mainly discussed in relation toconcrete objectsaccessible to sensory perception. It has been suggested that the beauty of a thingsuperveneson the sensory features of this thing.[10]It has also been proposed thatabstract objectslike stories or mathematical proofs can be beautiful.[11]Beauty plays a central role inworks of artand nature.[12][10]

An influential distinction among beautiful things, according toImmanuel Kant,is that betweenadherentbeauty (pulchritudo adhaerens)[note 1]andfree beauty(pulchritudo vaga). A thing has adherent beauty if its beauty depends on the conception or function of this thing, unlike free or absolute beauty.[10]Examples of adherent beauty include an ox which is beautiful as an ox but not beautiful as a horse[3]or a photograph which is beautiful, because it depicts a beautiful building but that lacks beauty generally speaking because of its low quality.[9]

Objectivism and subjectivism

Judgments of beauty seem to occupy an intermediary position between objective judgments, e.g. concerning the mass and shape of a grapefruit, and subjective likes, e.g. concerning whether the grapefruit tastes good.[13][10][9]Judgments of beauty differ from the former because they are based on subjective feelings rather than objective perception. But they also differ from the latter because they lay claim on universal correctness.[10]This tension is also reflected in common language. On the one hand, we talk about beauty as an objective feature of the world that is ascribed, for example, to landscapes, paintings or humans.[14]The subjective side, on the other hand, is expressed in sayings like "beauty is in the eye of the beholder".[3]

These two positions are often referred to asobjectivism(orrealism) andsubjectivism.[3]Objectivismis the traditional view, while subjectivism developed more recently inwestern philosophy.Objectivists hold that beauty is a mind-independent feature of things. On this account, the beauty of a landscape is independent of who perceives it or whether it is perceived at all.[3][9]Disagreements may be explained by an inability to perceive this feature, sometimes referred to as a "lack of taste".[15]Subjectivism, on the other hand, denies the mind-independent existence of beauty.[5][3][9]Influential for the development of this position wasJohn Locke's distinction betweenprimary qualities,which the object has independent of the observer, andsecondary qualities,which constitute powers in the object to produce certain ideas in the observer.[3][16][5]When applied to beauty, there is still a sense in which it depends on the object and its powers.[9]But this account makes the possibility of genuine disagreements about claims of beauty implausible, since the same object may produce very different ideas in distinct observers. The notion of "taste" can still be used to explain why different people disagree about what is beautiful, but there is no objectively right or wrong taste, there are just different tastes.[3]

The problem with both the objectivist and the subjectivist position in their extreme form is that each has to deny some intuitions about beauty. This issue is sometimes discussed under the label "antinomyof taste ".[3][4]It has prompted various philosophers to seek a unified theory that can take all these intuitions into account. One promising route to solve this problem is to move from subjective tointersubjective theories,which hold that the standards of validity of judgments of taste are intersubjective or dependent on a group of judges rather than objective. This approach tries to explain how genuine disagreement about beauty is possible despite the fact that beauty is a mind-dependent property, dependent not on an individual but a group.[3][4]A closely related theory sees beauty as asecondaryorresponse-dependent property.[9]On one such account, an object is beautiful "if it causes pleasure by virtue of its aesthetic properties".[5]The problem that different people respond differently can be addressed by combining response-dependence theories with so-calledideal-observer theories:it only matters how an ideal observer would respond.[10]There is no general agreement on how "ideal observers" are to be defined, but it is usually assumed that they are experienced judges of beauty with a fully developed sense of taste. This suggests an indirect way of solving theantinomy of taste:instead of looking fornecessary and sufficient conditionsof beauty itself, one can learn to identify the qualities of good critics and rely on their judgments.[3]This approach only works if unanimity among experts was ensured. But even experienced judges may disagree in their judgments, which threatens to undermine ideal-observer theories.[3][9]

Conceptions

Various conceptions of the essential features of beautiful things have been proposed but there is no consensus as to which is the right one.

Classical

The "classical conception" (seeClassicism) defines beauty in terms of the relation between the beautiful objectas a wholeand itsparts:the parts should stand in the right proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole.[3][5][9]On this account, which found its most explicit articulation in theItalian Renaissance,the beauty of a human body, for example, depends, among other things, on the right proportion of the different parts of the body and on the overall symmetry.[3]One problem with this conception is that it is difficult to give a general and detailed description of what is meant by "harmony between parts" and raises the suspicion that defining beauty through harmony results in exchanging one unclear term for another one.[3]Some attempts have been made to dissolve this suspicion by searching forlaws of beauty,like thegolden ratio.

18th century philosopherAlexander Baumgarten,for example, saw laws of beauty in analogy withlaws of natureand believed that they could be discovered through empirical research.[5]As of 2003, these attempts have failed to find a general definition of beauty and several authors take the opposite claim that such laws cannot be formulated, as part of their definition of beauty.[10]

Hedonism

A very common element in many conceptions of beauty is its relation topleasure.[11][5]Hedonism makes this relation part of the definition of beauty by holding that there is a necessary connection between pleasure and beauty, e.g. that for an object to be beautiful is for it to cause pleasure or that the experience of beauty is always accompanied by pleasure.[12]This account is sometimes labeled as "aesthetic hedonism" in order to distinguish it from other forms ofhedonism.[17][18]An influential articulation of this position comes fromThomas Aquinas,who treats beauty as "that which pleases in the very apprehension of it".[19]Immanuel Kantexplains this pleasure through a harmonious interplay between the faculties of understanding and imagination.[11]A further question for hedonists is how to explain the relation between beauty and pleasure. This problem is akin to theEuthyphro dilemma:is something beautiful because we enjoy it or do we enjoy it because it is beautiful?[5]Identity theorists solve this problem by denying that there is a difference between beauty and pleasure: they identify beauty, or the appearance of it, with the experience of aesthetic pleasure.[11]

Hedonists usually restrict and specify the notion of pleasure in various ways in order to avoid obvious counterexamples. One important distinction in this context is the difference betweenpureandmixed pleasure.[11]Pure pleasure excludes any form of pain or unpleasant feeling while the experience of mixed pleasure can include unpleasant elements.[20]But beauty can involve mixed pleasure, for example, in the case of a beautifully tragic story, which is why mixed pleasure is usually allowed in hedonist conceptions of beauty.[11]

Another problem faced by hedonist theories is that we take pleasure from many things that are not beautiful. One way to address this issue is to associate beauty with a special type of pleasure:aestheticordisinterested pleasure.[3][4][7]A pleasure is disinterested if it is indifferent to the existence of the beautiful object or if it did not arise owing to an antecedent desire through means-end reasoning.[21][11]For example, the joy of looking at a beautiful landscape would still be valuable if it turned out that this experience was an illusion, which would not be true if this joy was due to seeing the landscape as a valuable real estate opportunity.[3]Opponents of hedonism usually concede that many experiences of beauty are pleasurable but deny that this is true for all cases.[12]For example, a cold jaded critic may still be a good judge of beauty because of her years of experience but lack the joy that initially accompanied her work.[11]One way to avoid this objection is to allow responses to beautiful things to lack pleasure while insisting that all beautiful things merit pleasure, that aesthetic pleasure is the only appropriate response to them.[12]

Others

G. E. Mooreexplained beauty in regard tointrinsic valueas "that of which the admiring contemplation is good in itself".[21][5]This definition connects beauty to experience while managing to avoid some of the problems usually associated with subjectivist positions since it allows that things may be beautiful even if they are never experienced.[21]

Another subjectivist theory of beauty comes fromGeorge Santayana,who suggested that we project pleasure onto the things we call "beautiful". So in a process akin to acategory mistake,one treats one's subjective pleasure as an objective property of the beautiful thing.[11][3][5]Other conceptions include defining beauty in terms of a loving or longing attitude toward the beautiful object or in terms of its usefulness or function.[3][22]In 1871, functionalistCharles Darwinexplained beauty as result of accumulativesexual selectionin "The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex".[5]

In philosophy

Greco-Roman tradition

The classical Greek noun that best translates to the English-language words "beauty" or "beautiful" wasκάλλος,kallos,and the adjective was καλός,kalos.This is also translated as "good" or "of fine quality" and thus has a broader meaning than mere physical or material beauty. Similarly,kalloswas used differently from the English word beauty in that it first and foremost applied to humans and bears an erotic connotation.[23]TheKoine Greekword for beautiful was ὡραῖος,hōraios,[24]an adjective etymologically coming from the word ὥρα,hōra,meaning "hour". In Koine Greek, beauty was thus associated with "being of one's hour".[25]Thus, a ripe fruit (of its time) was considered beautiful, whereas a young woman trying to appear older or an older woman trying to appear younger would not be considered beautiful. In Attic Greek,hōraioshad many meanings, including "youthful" and "ripe old age".[25]Anotherclassicalterm in use to describe beauty waspulchrum(Latin).[26]

Beauty for ancient thinkers existed both inform,which is the material world as it is, and as embodied in the spirit, which is the world of mental formations.[27]Greek mythologymentionsHelen of Troyas the most beautiful woman.[28][29][30][31][32]Ancient Greek architectureis based on this view of symmetry andproportion.

Pre-Socratic

In one fragment ofHeraclitus'swritings (Fragment 106) he mentions beauty, this reads: "To God all things are beautiful, good, right..."[33]The earliest Western theory of beauty can be found in the works of early Greek philosophers from thepre-Socraticperiod, such asPythagoras,who conceived of beauty as useful for a moral education of the soul.[34]He wrote of how people experience pleasure when aware of a certain type of formal situation present in reality, perceivable by sight or through the ear[35]and discovered the underlying mathematical ratios in the harmonic scales in music.[34]ThePythagoreansconceived of the presence of beauty in universal terms, which is, as existing in a cosmological state, they observed beauty inthe heavens.[27]They saw a strong connection betweenmathematicsand beauty. In particular, they noted that objects proportioned according to thegolden ratioseemed more attractive.[36]

Classical period

Theclassicalconcept of beauty is one that exhibits perfect proportion (Wolfflin).[37]In this context, the concept belonged often within the discipline of mathematics.[26]An idea of spiritual beauty emerged during theclassical period,[27]beauty was something embodying divine goodness, while the demonstration of behaviour which might be classified as beautiful, from an inner state of morality which is aligned to thegood.[38]

The writing ofXenophonshows a conversation betweenSocratesandAristippus.Socrates discerned differences in the conception of the beautiful, for example, in inanimate objects, the effectiveness of execution of design was a deciding factor on the perception of beauty in something.[27]By the account of Xenophon, Socrates found beauty congruent with that to which was defined as the morally good, in short, he thought beauty coincident withthe good.[39]

Beauty is a subject ofPlatoin his workSymposium.[34]In the work, the high priestessDiotimadescribes how beauty moves out from a core singular appreciation of the body to outer appreciations via loved ones, to the world in its state of culture and society (Wright).[35]In other words, Diotoma gives to Socrates an explanation of how love should begin witherotic attachment,and end with the transcending of the physical to an appreciation of beauty as a thing in itself. The ascent of love begins with one's own body, then secondarily, in appreciating beauty in another's body, thirdly beauty in the soul, which cognates to beauty in the mind in the modern sense, fourthly beauty in institutions, laws and activities, fifthly beauty in knowledge, the sciences, and finally to lastly love beauty itself, which translates to the original Greek language term asautotokalon.[40]In the final state,auto to kalonand truth are united as one.[41]There is the sense in the text, concerning love and beauty they both co-exist but are still independent or, in other words, mutually exclusive, since love does not have beauty since it seeks beauty.[42]The work toward the end provides a description of beauty in a negative sense.[42]

Plato also discusses beauty in his workPhaedrus,[41]and identifies Alcibiades as beautiful inParmenides.[43]He considered beauty to be the Idea (Form) above all other Ideas.[44]Platonic thought synthesized beauty withthe divine.[35]Scruton(cited: Konstan) states Plato states of the idea of beauty, of it (the idea), being something inviting desirousness (c.fseducing), and, promotes anintellectualrenunciation(c.f.denouncing) of desire.[45]ForAlexander Nehamas,it is only the locating of desire to which the sense of beauty exists, in the considerations of Plato.[46]

Aristotledefines beauty inMetaphysicsas having order, symmetry and definitenesswhich the mathematical sciences exhibit to a special degree.[37]He saw a relationship between the beautiful (to kalon) and virtue, arguing that "Virtue aims at the beautiful."[47]

Roman

InDe Natura Deorum,Cicerowrote: "the splendour and beauty of creation", in respect to this, and all the facets of reality resulting from creation, he postulated these to be a reason to seethe existence of a God as creator.[48]

Western Middle Ages

In theMiddle Ages,Catholic philosopherslikeThomas Aquinasincluded beauty among thetranscendentalattributes ofbeing.[49]In hisSumma Theologica,Aquinas described the three conditions of beauty as: integritas (wholeness), consonantia (harmony and proportion), and claritas (a radiance and clarity that makes the form of a thing apparent to the mind).[50]

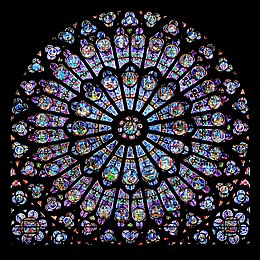

In the Gothic Architecture of theHighandLate Middle Ages,light was considered the most beautiful revelation ofGod,which was heralded in design.[1]Examples are thestained glassof GothicCathedralsincludingNotre-Dame de ParisandChartres Cathedral.[51]

St. Augustinesaid of beauty "Beauty is indeed a good gift of God; but that the good may not think it a great good, God dispenses it even to the wicked."[52]

Renaissance

Classical philosophyand sculptures of men and women produced according to theGreek philosophers' tenets of ideal human beauty were rediscovered inRenaissanceEurope, leading to a re-adoption of what became known as a "classical ideal". In terms of female human beauty, a woman whoseappearanceconforms to these tenets is still called a "classical beauty" or said to possess a "classical beauty", whilst the foundations laid by Greek and Roman artists have also supplied the standard for male beauty and female beauty in western civilization as seen, for example, in theWinged Victory of Samothrace.During the Gothic era, the classical aesthetical canon of beauty was rejected as sinful. Later,RenaissanceandHumanistthinkers rejected this view, and considered beauty to be the product of rational order and harmonious proportions. Renaissance artists and architects (such asGiorgio Vasariin his "Lives of Artists" ) criticised the Gothic period as irrational and barbarian. This point of view ofGothic artlasted until Romanticism, in the 19th century. Vasari aligned himself to the classical notion and thought of beauty as defined as arising fromproportionand order.[38]

Age of Reason

TheAge of Reasonsaw a rise in an interest in beauty as a philosophical subject. For example, Scottish philosopherFrancis Hutchesonargued that beauty is "unity in varietyand variety in unity ".[54]He wrote that beauty was neither purely subjective nor purely objective—it could be understood not as "any Quality suppos'd to be in the Object, which should of itself be beautiful, without relation to any Mind which perceives it: For Beauty, like other Names of sensible Ideas, properly denotes thePerceptionof some mind;... however we generally imagine that there is something in the Object just like our Perception. "[55]

Immanuel Kantbelieved that there could be no "universal criterion of the beautiful" and that the experience of beauty is subjective, but that an object is judged to be beautiful when it seems to display "purposiveness"; that is, when its form is perceived to have the character of a thing designed according to some principle and fitted for a purpose.[56]He distinguished "free beauty" from "merely adherent beauty", explaining that "the first presupposes no concept of what the object ought to be; the second does presuppose such a concept and the perfection of the object in accordance therewith."[57]By this definition, free beauty is found in seashells and wordless music; adherent beauty in buildings and the human body.[57]

The Romantic poets, too, became highly concerned with thenatureof beauty, withJohn Keatsarguing inOde on a Grecian Urnthat:

- Beauty is truth, truth beauty, —that is all

- Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Western 19th and 20th century

In the Romantic period,Edmund Burkepostulated a difference between beauty in its classical meaning and thesublime.[58]The concept of the sublime, as explicated by Burke andKant,suggested viewing Gothic art and architecture, though not in accordance with the classical standard of beauty, as sublime.[59]

The 20th century saw an increasing rejection of beauty by artists and philosophers alike, culminating inpostmodernism's anti-aesthetics.[60]This is despite beauty being a central concern of one of postmodernism's main influences,Friedrich Nietzsche,who argued that the Will to Power was the Will to Beauty.[61]

In the aftermath of postmodernism's rejection of beauty, thinkers have returned to beauty as an important value. American analytic philosopherGuy Sircelloproposed his New Theory of Beauty as an effort to reaffirm the status of beauty as an important philosophical concept.[62][63]He rejected the subjectivism of Kant and sought to identify the properties inherent in an object that make it beautiful. He called qualities such as vividness, boldness, and subtlety "properties of qualitative degree" (PQDs) and stated that a PQD makes an object beautiful if it is not—and does not create the appearance of— "a property of deficiency, lack, or defect"; and if the PQD is strongly present in the object.[64]

Elaine Scarryargues that beauty is related to justice.[65]

Beauty is also studied by psychologists and neuroscientists in the field ofexperimental aestheticsandneuroestheticsrespectively. Psychological theories see beauty as a form ofpleasure.[66][67]Correlational findings support the view that more beautiful objects are also more pleasing.[68][69][70]Some studies suggest that higher experienced beauty is associated with activity in the medialorbitofrontal cortex.[71][72]This approach of localizing the processing of beauty in one brain region has received criticism within the field.[73]

Philosopher and novelistUmberto EcowroteOn Beauty: A History of a Western Idea(2004)[74][75]andOn Ugliness(2007).[76]The narrator of his novelThe Name of the Rosefollows Aquinas in declaring: "three things concur in creating beauty: first of all integrity or perfection, and for this reason, we consider ugly all incomplete things; then proper proportion or consonance; and finally clarity and light", before going on to say "the sight of the beautiful implies peace".[77][78]Mike Phillips has described Umberto Eco'sOn Beautyas "incoherent" and criticized him for focusing only on Western European history and devoting none of his book to Eastern European, Asian, or African history.[75]Amy Finnerty described Eco's workOn Uglinessfavorably.[79]

Chinese philosophy

Chinese philosophyhas traditionally not made a separate discipline of the philosophy of beauty.[80]Confuciusidentified beauty with goodness, and considered a virtuous personality to be the greatest of beauties: In his philosophy, "a neighborhood with arenman in it is a beautiful neighborhood. "[81]Confucius's studentZeng Shenexpressed a similar idea: "few men could see the beauty in some one whom they dislike."[81]Menciusconsidered "complete truthfulness" to be beauty.[82]Zhu Xisaid: "When one has strenuously implemented goodness until it is filled to completion and has accumulated truth, then the beauty will reside within it and will not depend on externals."[82]

Human attributes

The word "beauty" is often[how often?]used as a countable noun to describe a beautiful woman.[83][84]

The characterization of a person as "beautiful", whether on an individual basis or by community consensus, is often[how often?]based on some combination ofinner beauty,which includes psychological factors such aspersonality,intelligence,grace,politeness,charisma,integrity,congruenceandelegance,andouter beauty(i.e.physical attractiveness) which includes physical attributes which are valued on an aesthetic basis.[citation needed]

Standards of beauty have changed over time, based on changing cultural values. Historically, paintings show a wide range of different standards for beauty.[85][86]

A strong indicator of physical beauty is "averageness".[87][88]When images of human faces are averaged together to form a composite image, they become progressively closer to the "ideal" image and are perceived as more attractive. This was first noticed in 1883, whenFrancis Galtonoverlaid photographic composite images of the faces of vegetarians and criminals to see if there was a typical facial appearance for each. When doing this, he noticed that the composite images were more attractive as compared to any of the individual images.[89]Researchers have replicated the result under more controlled conditions and found that the computer-generated, mathematical average of a series of faces is rated more favorably than individual faces.[90]It is argued that it is evolutionarily advantageous that sexual creatures are attracted to mates who possess predominantly common or average features, because it suggests theabsence of genetic or acquired defects.[91][92][93]

Since the 1970's there has been increasing evidence that a preference for beautiful faces emerges early in infancy, and is probably innate,[94][95][96] and that the rules by which attractiveness is established are similar across different genders and cultures.[97][98]

A feature of beautiful women which has been explored by researchers is awaist–hip ratioof approximately 0.70. As of 2004, physiologists had shown that women withhourglass figureswere more fertile than other women because of higher levels of certain female hormones, a fact that may subconsciously condition males choosing mates.[99][100]In 2008, other commentators have suggested that this preference may not be universal. For instance, in some non-Western cultures in which women have to do work such as finding food, men tend to have preferences for higher waist-hip ratios.[101][102][103]

Exposure to the thin ideal in mass media, such as fashion magazines, directly correlates with body dissatisfaction, low self-esteem, and the development of eating disorders among female viewers.[104][105]Further, the widening gap between individual body sizes and societal ideals continues to breed anxiety among young girls as they grow, highlighting the dangerous nature of beauty standards in society.[106]

Western concept

A study usingChineseimmigrants andHispanic,BlackandWhiteAmerican citizensfound that their ideals of female beauty were not significantly different.[109]Participants in the study ratedAsianandLatinawomen as more attractive thanWhiteandBlack women,and it was found that Asian and Latina women had more of the attributes that were considered attractive for women.[110]Exposure toWestern mediadid not influence or improve the Asian men's ratings of White women.[111]

One study found thatEast Asian womenin the United States are closer to the ideal figure promoted in Western media, and that East Asian women conform to both Western and Eastern influences in the United States.[112][113]East Asian men were found to be more impacted by Western beauty ideals then East Asian women, in the United States. East Asian men felt as though their bodies were not large enough and therefore deviated from the Western norm.[114]East Asian men and white Western women were found to have the highest levels of body dissatisfaction in the United States.[115]A study ofAfrican AmericanandSouth Asianwomen found that some had internalized a white beauty ideal that placed light skin and straight hair at the top.[116]

Eurocentric standards for men include tallness, leanness, and muscularity, which have been idolized through American media, such as inHollywoodfilms and magazine covers.[117]

In of the United States,African Americanshave historically been subjected to beauty ideals that often do not reflect their own appearance, which can lead to issues of low self-esteem. African-American philosopherCornel Westelaborates that, "much of black self-hatred and self-contempt has to do with the refusal of many black Americans to love their own black bodies-especially their black noses, hips, lips, and hair."[118]According to Patton (2006), the stereotype of African-American women's inferiority (relative to other races of women) maintains a system of oppression based on race and gender that operates to the detriment of women of all races, and also black men.[119]In the 1960s, theblack is beautifulcultural movement sought to dispel the notion of aEurocentricconcept of beauty.[120]

Much criticism has been directed at models of beauty which depend solely upon Western ideals of beauty, as seen, for example, in theBarbiefranchise. Criticisms of Barbie are often centered around concerns that children consider Barbie a role model of beauty and will attempt to emulate her. One of the most common criticisms of Barbie is that she promotes an unrealistic idea of body image for a young woman, leading to a risk that girls who attempt to emulate her will becomeanorexic.[121]

As of 1998, these criticisms of the lack of diversity in such franchises as theBarbiemodel of beauty in Western culture, had led to a dialogue to create non-exclusive models of Western ideals in body type for young girls who do not match the thinness ideal that Barbie represents.[122]Mattel responded to these criticisms.

In East Asian cultures, familial pressures and cultural norms shape beauty ideals. A 2017 experimental study concluded that Asian cultural idealization of "fragile" girls was impacting Asian American women's lifestyle, eating, and appearance choices.[123]

Effects on society

Researchers have found that good-looking students get higher grades from their teachers than students with an ordinary appearance.[124]Some studies using mock criminal trials have shown that physically attractive "defendants" are less likely to be convicted—and if convicted are likely to receive lighter sentences—than less attractive ones (although the opposite effect was observed when the alleged crime was swindling, perhaps because jurors perceived the defendant's attractiveness as facilitating the crime).[125]Studies among teens and young adults, such as those of psychiatrist and self-help authorEva Ritvoshow that skin conditions have a profound effect on social behavior and opportunity.[126]

How much money a person earns may also be influenced by physical beauty. One study found that people low in physical attractiveness earn 5 to 10 percent less than ordinary-looking people, who in turn earn 3 to 8 percent less than those who are considered good-looking.[127]In the market for loans, the least attractive people are less likely to get approvals, although they are less likely to default. In the marriage market, women's looks are at a premium, but men's looks do not matter much.[128]The impact of physical attractiveness on earnings varies across races, with the largest beauty wage gap among black women and black men.[129]

Conversely, being very unattractive increases the individual's propensity for criminal activity for a number of crimes ranging from burglary to theft to selling illicit drugs.[130]

Discrimination against others based on their appearance is known aslookism.[131]

See also

Notes

- ^Translated inZangwillasdependentbeauty

References

- ^abStegers, Rudolf (2008).Sacred Buildings: A Design Manual.Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 60.ISBN3764382767.

- ^Gary Martin (2007)."Beauty is in the eye of the beholder".The Phrase Finder.Archivedfrom the original on November 30, 2007.RetrievedDecember 4,2007.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvSartwell, Crispin (2017)."Beauty".The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.Archivedfrom the original on February 26, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^abcde"Aesthetics".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on February 28, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 9,2021.

- ^abcdefghijkl"Beauty and Ugliness".Encyclopedia.com.Archivedfrom the original on December 24, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 9,2021.

- ^ab"Beauty in Aesthetics".Encyclopedia.com.Archivedfrom the original on January 13, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 9,2021.

- ^abLevinson, Jerrold (2003). "Philosophical Aesthetics: An Overview".The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics.Oxford University Press. pp. 3–24.Archivedfrom the original on February 10, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Kriegel, Uriah (2019)."The Value of Consciousness".Analysis.79(3): 503–520.doi:10.1093/analys/anz045.ISSN0003-2638.Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^abcdefghijDe Clercq, Rafael (2013). "Beauty".The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics.Routledge.Archivedfrom the original on January 13, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^abcdefghiZangwill, Nick (2003). "Beauty". In Levinson, Jerrold (ed.).Oxford Handbook to Aesthetics.Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199279456.003.0018.Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 16,2021.

- ^abcdefghiDe Clercq, Rafael (2019)."Aesthetic Pleasure Explained".Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism.77(2): 121–132.doi:10.1111/jaac.12636.

- ^abcdGorodeisky, Keren (2019). "On Liking Aesthetic Value".Philosophy and Phenomenological Research.102(2): 261–280.doi:10.1111/phpr.12641.S2CID204522523.

- ^Honderich, Ted (2005). "Aesthetic judgment".The Oxford Companion to Philosophy.Oxford University Press.Archivedfrom the original on January 29, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Scruton, Roger (2011).Beauty: A Very Short Introduction.Oxford University Press. p. 5.Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Rogerson, Kenneth F. (1982)."The Meaning of Universal Validity in Kant's Aesthetics".The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism.40(3): 304.doi:10.2307/429687.JSTOR429687.Archivedfrom the original on February 10, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Uzgalis, William (2020)."John Locke".The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.Archivedfrom the original on April 24, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 9,2021.

- ^Berg, Servaas Van der (2020)."Aesthetic Hedonism and Its Critics".Philosophy Compass.15(1): e12645.doi:10.1111/phc3.12645.S2CID213973255.Archivedfrom the original on February 11, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Matthen, Mohan; Weinstein, Zachary."Aesthetic Hedonism".Oxford Bibliographies.Archivedfrom the original on January 18, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Honderich, Ted (2005). "Beauty".The Oxford Companion to Philosophy.Oxford University Press.Archivedfrom the original on January 29, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Spicher, Michael R."Aesthetic Taste".Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Archivedfrom the original on February 14, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^abcCraig, Edward (1996). "Beauty".Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Routledge.Archivedfrom the original on January 16, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Hansson, Sven Ove (2005)."Aesthetic Functionalism".Contemporary Aesthetics.3.Archivedfrom the original on February 13, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^Konstan, David (2014).Beauty - The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea.New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 30–35.ISBN978-0-19-992726-5.

- ^Matthew 23:27, Acts 3:10, Flavius Josephus, 12.65

- ^abEuripides,Alcestis515.

- ^abG Parsons (2008).Aesthetics and Nature.A&C Black. p. 7.ISBN978-0826496768.Archivedfrom the original on February 3, 2023.RetrievedMay 11,2015.

- ^abcdJ. Harrell; C. Barrett; D. Petsch, eds. (2006).History of Aesthetics.A&C Black. p. 102.ISBN0826488552.Archivedfrom the original on February 3, 2023.RetrievedMay 11,2015.

- ^P.T. Struck -The Trojan WarArchivedDecember 22, 2021, at theWayback MachineClassics Department of University of Penn [Retrieved 2015-05-12]( < 1250> )

- ^R Highfield -Scientists calculate the exact date of the Trojan horse using eclipse in HomerArchivedDecember 24, 2021, at theWayback MachineTelegraph Media Group Limited 24 Jun 2008 [Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^Bronze Age first sourceC Freeman -Egypt, Greece, and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean- p.116ArchivedFebruary 3, 2023, at theWayback Machine,verified atA. F. Harding -European Societies in the Bronze Age- p.1ArchivedFebruary 3, 2023, at theWayback Machine[Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^Sources for War with TroyArchivedDecember 8, 2015, at theWayback MachineCambridge University Classics Department [Retrieved 2015-05-12]( < 750, 850 > )

- ^the most beautiful-C.Braider -The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism: Volume 3ArchivedFebruary 3, 2023, at theWayback Machine,The Renaissance: Zeuxis portrait (p.174)ISBN0521300088- Ed. G.A. Kennedy, G.P. Norton &The British Museum -Helen runs off with ParisArchivedOctober 11, 2015, at theWayback Machine[Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^W.W. Clohesy -The Strength of the Invisible: Reflections on Heraclitus (p.177)ArchivedAugust 12, 2017, at theWayback MachineAuslegung Volume XIIIISSN0733-4311[Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^abcFistioc, M.C. (December 5, 2002).The Beautiful Shape of the Good: Platonic and Pythagorean Themes in Kant's Critique of the Power of Judgment.Review by S Naragon, Manchester College. Routledge, 2002 (University of Notre Dame philosophy reviews).Archivedfrom the original on January 22, 2016.RetrievedMay 11,2015.

- ^abcJ.L. Wright.Review of The Beautiful Shape of the Good:Platonic and Pythagorean Themes in Kant's Critique of the Power of Judgment by M.C.FistiocVolume 4 Issue 2 Medical Research Ethics.Pacific University Library. Archived fromthe originalon March 4, 2016.RetrievedMay 11,2015.(ed. 4th paragraph -beauty and the divine)

- ^Seife, Charles (2000).Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea.Penguin. p. 32.ISBN0-14-029647-6.

- ^abSartwell, C. Edward N. Zalta (ed.).Beauty.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition).Archivedfrom the original on January 18, 2021.RetrievedMay 11,2015.

- ^abL Cheney (2007).Giorgio Vasari's Teachers: Sacred & Profane Art.Peter Lang. p. 118.ISBN978-0820488134.Archivedfrom the original on February 3, 2023.RetrievedMay 11,2015.

- ^N Wilson -Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece(p.20) Routledge, 31 Oct 2013ISBN113678800X[Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^K Urstad.Loving Socrates:The Individual and the Ladder of Love in Plato'sSymposium(PDF).Res Cogitans 2010 no.7, vol. 1. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on October 10, 2015.RetrievedMay 11,2015.

- ^abW. K. C. Guthrie; J. Warren (2012).The Greek Philosophers from Thales to Aristotle (p.112).Routledge.ISBN978-0415522281.RetrievedMay 12,2015.

- ^abA Preus (1996).Notes on Greek Philosophy from Thales to Aristotle (parts 198 and 210).Global Academic Publishing.ISBN1883058090.RetrievedMay 12,2015.

- ^S Scolnicov (2003).Plato's Parmenides.University of California Press. p. 21.ISBN0520925114.RetrievedMay 12,2015.

- ^Phaedrus

- ^D. Konstan (2014).Beauty - The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea.published by Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0199927265.RetrievedNovember 24,2015.

- ^F. McGhee -review of text written by David Konstan[usurped]published by theOxonian ReviewMarch 31, 2015 [Retrieved 2015-11-24](references not sources:Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2014.06.08 (Donald Sells)ArchivedNovember 26, 2014, at theWayback Machine+DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199605507.001.0001ArchivedJuly 16, 2020, at theWayback Machine)

- ^Nicomachean Ethics

- ^M Garani (2007).Empedocles Redivivus: Poetry and Analogy in Lucretius.Routledge.ISBN978-1135859831.Archivedfrom the original on February 3, 2023.RetrievedMay 12,2015.

- ^Eco, Umberto (1988).The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas.Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ. Press. p. 98.ISBN0674006755.

- ^McNamara, Denis Robert (2009).Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy.Hillenbrand Books. pp. 24–28.ISBN1595250271.

- ^Duiker, William J., and Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2019).World History.United States: Cengage Learning. p. 351.ISBN1337401048

- ^"NPNF1-02. St. Augustine's City of God and Christian Doctrine - Christian Classics Ethereal Library".CCEL.Archivedfrom the original on July 1, 2017.RetrievedMay 1,2018.

- ^Ames-Lewis, Francis (2000),The Intellectual Life of the Early Renaissance Artist,New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, p. 194,ISBN0-300-09295-4

- ^Francis Hutcheson (1726).An Inquiry Into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue: In Two Treatises.J. Darby.ISBN9780598982698.Archivedfrom the original on February 3, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2020.

- ^Kennick, William Elmer (1979).Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics; 2nd ed.New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 421.ISBN0312053916.

- ^Kennick, William Elmer (1979).Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics; 2nd ed.New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 482–483.ISBN0312053916.

- ^abKennick, William Elmer (1979).Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics; 2nd ed.New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 517.ISBN0312053916.

- ^Doran, Robert (2017).The Theory of the Sublime from Longinus to Kant.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 144.ISBN1107499151.

- ^Monk, Samuel Holt (1960).The Sublime: A Study of Critical Theories in XVIII-century England.Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 6–9, 141.OCLC943884.

- ^Hal Foster (1998).The Anti-aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture.New Press.ISBN978-1-56584-462-9.

- ^Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1967).The Will To Power.Random House.ISBN978-0-394-70437-1.

- ^Guy Sircello,A New Theory of Beauty.Princeton Essays on the Arts, 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- ^Love and Beauty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- ^Kennick, William Elmer (1979).Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics; 2nd ed.New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 535–537.ISBN0312053916.

- ^Elaine Scarry (November 4, 2001).On Beauty and Being Just.Princeton University Press.ISBN0-691-08959-0.

- ^Reber, Rolf; Schwarz, Norbert; Winkielman, Piotr (November 2004). "Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver's Processing Experience?".Personality and Social Psychology Review.8(4): 364–382.doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3.hdl:1956/594.PMID15582859.S2CID1868463.

- ^Armstrong, Thomas; Detweiler-Bedell, Brian (December 2008). "Beauty as an Emotion: The Exhilarating Prospect of Mastering a Challenging World".Review of General Psychology.12(4): 305–329.CiteSeerX10.1.1.406.1825.doi:10.1037/a0012558.S2CID8375375.

- ^Vartanian, Oshin; Navarrete, Gorka; Chatterjee, Anjan; Fich, Lars Brorson; Leder, Helmut; Modroño, Cristián; Nadal, Marcos; Rostrup, Nicolai; Skov, Martin (June 18, 2013)."Impact of contour on aesthetic judgments and approach-avoidance decisions in architecture".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.110(Suppl 2): 10446–10453.doi:10.1073/pnas.1301227110.PMC3690611.PMID23754408.

- ^Marin, Manuela M.; Lampatz, Allegra; Wandl, Michaela; Leder, Helmut (November 4, 2016)."Berlyne Revisited: Evidence for the Multifaceted Nature of Hedonic Tone in the Appreciation of Paintings and Music".Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.10:536.doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00536.PMC5095118.PMID27867350.

- ^Brielmann, Aenne A.; Pelli, Denis G. (May 2017)."Beauty Requires Thought".Current Biology.27(10): 1506–1513.e3.Bibcode:2017CBio...27E1506B.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.018.PMC6778408.PMID28502660.

- ^Kawabata, Hideaki; Zeki, Semir (April 2004). "Neural Correlates of Beauty".Journal of Neurophysiology.91(4): 1699–1705.doi:10.1152/jn.00696.2003.PMID15010496.S2CID13828130.

- ^Ishizu, Tomohiro; Zeki, Semir (July 6, 2011)."Toward A Brain-Based Theory of Beauty".PLOS ONE.6(7): e21852.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621852I.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021852.PMC3130765.PMID21755004.

- ^Conway, Bevil R.; Rehding, Alexander (March 19, 2013)."Neuroaesthetics and the Trouble with Beauty".PLOS Biology.11(3): e1001504.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001504.PMC3601993.PMID23526878.

- ^Eco, Umberto (2004).On Beauty: A historyof a western idea.London: Secker & Warburg.ISBN978-0436205170.

- ^abPhillips, Mike (January 29, 2005)."Review: On Beauty edited by Umberto Eco".the Guardian.RetrievedJune 3,2023.

- ^Eco, Umberto (2007).On Ugliness.London: Harvill Secker.ISBN9781846551222.

- ^Eco, Umberto (1980).The Name of the Rose.London: Vintage. p. 65.ISBN9780099466031.

- ^Fasolini, Diego (2006). "The Intrusion of Laughter into the Abbey of Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose: The Christian paradox of Joy Mingling with Sorrow".Romance Notes.46(2): 119–129.JSTOR43801801.

- ^"Edited by Umberto Eco - Book Review - The New York Times".On Ugliness.December 2, 2007.RetrievedJune 3,2023.

- ^The Chinese Text: Studies in Comparative Literature(1986). Cocos (Keeling) Islands: Chinese University Press. p. 119.ISBN962201318X.

- ^abChang, Chi-yun (2013).Confucianism: A Modern Interpretation (2012 Edition).Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 213.ISBN9814439894

- ^abTang, Yijie (2015).Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, Christianity and Chinese Culture.Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 242.ISBN3662455331

- ^"Beauty | Definition of Beauty by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com".Lexico Dictionaries | English.Archived fromthe originalon August 9, 2020.RetrievedAugust 1,2020.

- ^"BEAUTY (noun) American English definition and synonyms | Macmillan Dictionary".Macmillan Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on July 9, 2017.RetrievedAugust 1,2020.

- ^Artists' Types of BeautyArchivedFebruary 3, 2023, at theWayback Machine",The Strand Magazine.United Kingdom, G. Newnes, 1904. pp. 291–298.

- ^Chō, Kyō (2012).The Search for the Beautiful Woman: A Cultural History of Japanese and Chinese Beauty.Translated bySelden, Kyoko Iriye.Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 100–102.ISBN978-1442218956..

- ^Langlois, Judith H.; Roggman, Lori A. (1990). "Attractive Faces Are Only Average".Psychological Science.1(2): 115–121.doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00079.x.S2CID18557871.

- ^Strauss, Mark S. (1979). "Abstraction of prototypical information by adults and 10-month-old infants".Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory.5(6): 618–632.doi:10.1037/0278-7393.5.6.618.PMID528918.

- ^Galton, Francis (1879)."Composite Portraits, Made by Combining Those of Many Different Persons Into a Single Resultant Figure".The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.8.JSTOR: 132–144.doi:10.2307/2841021.ISSN0959-5295.JSTOR2841021.Archivedfrom the original on July 26, 2020.RetrievedJune 14,2020.

- ^Langlois, Judith H.; Roggman, Lori A.; Musselman, Lisa (1994). "What Is Average and What Is Not Average About Attractive Faces?".Psychological Science.5(4). SAGE Publications: 214–220.doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00503.x.ISSN0956-7976.S2CID145147905.

- ^Koeslag, Johan H. (1990). "Koinophilia groups sexual creatures into species, promotes stasis, and stabilizes social behaviour".Journal of Theoretical Biology.144(1). Elsevier BV: 15–35.Bibcode:1990JThBi.144...15K.doi:10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80297-8.ISSN0022-5193.PMID2200930.

- ^Symons, D. (1979)The Evolution of Human Sexuality.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^Highfield, Roger(May 7, 2008)."Why beauty is an advert for good genes".The Daily Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 13,2012.

- ^Slater, Alan; Von der Schulenburg, Charlotte; Brown, Elizabeth; Badenoch, Marion; Butterworth, George; Parsons, Sonia; Samuels, Curtis (1998). "Newborn infants prefer attractive faces".Infant Behavior and Development.21(2). Elsevier BV: 345–354.doi:10.1016/s0163-6383(98)90011-x.ISSN0163-6383.

- ^Kramer, Steve;Zebrowitz, Leslie;Giovanni, Jean Paul San; Sherak, Barbara (February 21, 2019). "Infants' Preferences for Attractiveness and Babyfaceness".Studies in Perception and Action III.Routledge. pp. 389–392.doi:10.4324/9781315789361-103.ISBN978-1-315-78936-1.S2CID197734413.

- ^Langlois, Judith H.; Ritter, Jean M.; Roggman, Lori A.; Vaughn, Lesley S. (1991). "Facial diversity and infant preferences for attractive faces".Developmental Psychology.27(1). American Psychological Association (APA): 79–84.doi:10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.79.ISSN1939-0599.

- ^Apicella, Coren L; Little, Anthony C; Marlowe, Frank W (2007). "Facial Averageness and Attractiveness in an Isolated Population of Hunter-Gatherers".Perception.36(12). SAGE Publications: 1813–1820.doi:10.1068/p5601.ISSN0301-0066.PMID18283931.S2CID37353815.

- ^Rhodes, Gillian (2006). "The Evolutionary Psychology of Facial Beauty".Annual Review of Psychology.57(1). Annual Reviews: 199–226.doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208.ISSN0066-4308.PMID16318594.

- ^"Hourglass figure fertility link".BBC News.May 4, 2004.Archivedfrom the original on October 11, 2011.RetrievedJuly 1,2018.

- ^Bhattacharya, Shaoni (May 5, 2004)."Barbie-shaped women more fertile".New Scientist.Archivedfrom the original on July 10, 2018.RetrievedJuly 1,2018.

- ^"Best Female Figure Not an Hourglass".Live Science.December 3, 2008.Archivedfrom the original on July 10, 2018.RetrievedJuly 1,2018.

- ^Locke, Susannah (June 22, 2014)."Did evolution really make men prefer women with hourglass figures?".Vox.Archivedfrom the original on July 10, 2018.RetrievedJuly 1,2018.

- ^Begley, Sharon."Hourglass Figures: We Take It All Back".Sharon Begley.Archivedfrom the original on July 10, 2018.RetrievedJuly 1,2018.

- ^"Media & Eating Disorders".National Eating Disorders Association.October 5, 2017.Archivedfrom the original on December 2, 2018.RetrievedNovember 27,2018.

- ^"Model's link to teenage anorexia".BBC News.May 30, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on April 13, 2020.RetrievedOctober 25,2009.

- ^Jade, Deanne."National Centre for Eating Disorders - The Media & Eating Disorders".National Centre for Eating Disorders.Archivedfrom the original on December 24, 2018.RetrievedNovember 27,2018.

- ^"A Woman's Face is Her Fortune (advertisement)".The Helena Independent.November 9, 2000. p. 7.

- ^Little, Becky (September 22, 2016)."Arsenic Pills and Lead Foundation: The History of Toxic Makeup".National Geographic.Archived fromthe originalon November 5, 2018.

- ^Cunningham, Michael (1995). ""Their ideas of beauty are, on the whole, the same as ours": Consistency and variability in the cross-cultural perception of female physical attractiveness ".Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.68(2): 261–279.doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.2.261.ISSN1939-1315.

- ^Cunningham 1995,p. 1995: "All groups of judges made more positive ratings of the Asian and Hispanic targets compared with the Black and White targets. Further analyses indicated that the Asian and Hispanic targets happened to possess significantly larger eye height, eye width, nose width, eyebrow height, smile width, and upper lip width than the White and Black women".

- ^Cunningham 1995,p. 271: "The four-item measure of exposure to Western culture was not reliably associated with giving higher ratings to Whites (r =. 19, n s). The relation of rating Whites to frequency of viewing Western television, for example, was quite low (r=.01)."

- ^Barnett, Heather L.; Keel, P.; Conoscenti, Lauren M. (2001). "Body Type Preferences in Asian and Caucasian College Students".Sex Roles.45(11/12): 875-875.doi:10.1023/A:1015600705749.S2CID141429057.

- ^Barnett, Keel & Conoscenti 2001,p. 875: "Rieger et al. (2001) argue that traditional values and practices in Asian cultures also idealize thinness. Virtues of fasting that results in emaciation are quoted from the Daoist text Sandong zhunang (Rieger et al., 2001). Thus, while Caucasian and Asian women may be exposed to similar ideals of attractiveness, and Asian women are nearer to weight ideals portrayed by the media, both traditional and western values may contribute to the internalization of extremely thin ideals by Asian females."

- ^Barnett, Keel & Conoscenti 2001,p. 875: "Additionally, ethnic facial features may contribute to a general feeling of deviating from the norm, leading Asian or Asian American men to focus on a seemingly mutable quality, body weight. Further, Asian men were more likely than Caucasian men to select an ideal body figure that was similar to the figure they thought most attractive to the opposite sex. This suggests that Asian males may be more invested in achieving a larger body in order to attract a romantic partner. Finally, Asian males may be negatively affected by efforts to acculturate to Western society. A recent study revealed that acculturation is positively related to perfectionism in Asian males but not Asian females (Davis & Katzman, 1999)."

- ^Barnett, Keel & Conoscenti 2001,p. 875: "" Specifically, Asian males reported an ideal figure that was larger than their current figure. An interaction between gender and ethnicity revealed that Caucasian females and Asian males reported the largest degree of body dissatisfaction. "

- ^Harper, Kathryn; Choma, Becky L. (October 5, 2018). "Internalised White Ideal, Skin Tone Surveillance, and Hair Surveillance Predict Skin and Hair Dissatisfaction and Skin Bleaching among African American and Indian Women".Sex Roles.80(11–12): 735–744.doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0966-9.ISSN0360-0025.S2CID150156045.

- ^Pompper, D.; Allison, M.C. (2022).Rhetoric of Masculinity: Male Body Image, Media, and Gender Role Stress/Conflict.Lexington Books. pp. 82–83.ISBN978-1-7936-2689-9.RetrievedJune 3,2023.

- ^West, C. (2017).Race Matters, 25th Anniversary: With a New Introduction.Beacon Press. p. 85.ISBN978-0-8070-0883-6.RetrievedJune 1,2023.

- ^Patton, Tracey Owens (July 2006). "Hey Girl, Am I More than My Hair?: African American Women and Their Struggles with Beauty, Body Image, and Hair".NWSA Journal.18(2): 45–46.doi:10.2979/NWS.2006.18.2.24(inactive July 17, 2024).JSTOR4317206.Project MUSE199496ProQuest233235409.

These stereotypes and the culture that sustains them exist to define the social position of black women as subordinate on the basis of gender to all men, regardless of color, and on the basis of race to all other women. These negative images also are indispensable to the maintenance of an interlocking system of oppression based on race and gender that operates to the detriment of all women and all blacks "(Caldwell 2000, 280).

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2024 (link) - ^DoCarmo, Stephen."Notes on the Black Cultural Movement".Bucks County Community College. Archived fromthe originalon April 8, 2005.RetrievedNovember 27,2007.

- ^Dittmar, Helga; Halliwell, Emma; Ive, Suzanne (March 2006). "Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls".Developmental Psychology.42(2): 283–292.doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283.PMID16569167.

- ^Flett, G.L.; Kocovski, N.; Davison, G.C.; Neale, J.M.; Blankstein, K.R. (2017).Abnormal Psychology, Sixth Canadian Edition Loose-Leaf Print Companion(in Welsh). John Wiley & Sons Canada, Limited. p. 292.ISBN978-1-119-44409-1.RetrievedJanuary 11,2024.

- ^Wong, Stephanie N.; Keum, Brian TaeHyuk; Caffarel, Daniel; Srinivasan, Ranjana; Morshedian, Negar; Capodilupo, Christina M.; Brewster, Melanie E. (December 2017). "Exploring the conceptualization of body image for Asian American women".Asian American Journal of Psychology.8(4): 296–307.doi:10.1037/aap0000077.S2CID151560804.

- ^Begley, Sharon(July 14, 2009)."The Link Between Beauty and Grades".Newsweek.Archivedfrom the original on April 20, 2010.RetrievedMay 31,2010.

- ^Amina A Memon; Aldert Vrij; Ray Bull (October 31, 2003).Psychology and Law: Truthfulness, Accuracy and Credibility.John Wiley & Sons. pp. 46–47.ISBN978-0-470-86835-5.

- ^"Image survey reveals" perception is reality "when it comes to teenagers"(Press release). multivu.prnewswire.com.Archivedfrom the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^Lorenz, K. (2005)."Do pretty people earn more?".CNN News.Time Warner.Cable News Network.Archivedfrom the original on October 12, 2015.RetrievedJanuary 31,2007.

- ^Daniel Hamermesh; Stephen J. Dubner (January 30, 2014)."Reasons to not be ugly: full transcript".Freakonomics.Archivedfrom the original on March 1, 2014.RetrievedMarch 4,2014.

- ^Monk, Ellis P.; Esposito, Michael H.; Lee, Hedwig (July 1, 2021). "Beholding Inequality: Race, Gender, and Returns to Physical Attractiveness in the United States".American Journal of Sociology.127(1): 194–241.doi:10.1086/715141.S2CID235473652.

- ^Erdal Tekin; Stephen J. Dubner (January 30, 2014)."Reasons to not be ugly: full transcript".Freakonomics.Archivedfrom the original on March 1, 2014.RetrievedMarch 4,2014.

- ^Leo Gough (June 29, 2011).C. Northcote Parkinson's Parkinson's Law: A modern-day interpretation of a management classic.Infinite Ideas. p. 36.ISBN978-1-908189-71-4.

Further reading

- Richard O. Prum (2018).The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin's Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World - and Us.Anchor.ISBN978-0345804570.

- Liebelt, C. (2022),Beauty: What Makes Us Dream, What Haunts Us.Feminist Anthropology.

External links

- Sartwell, Crispin."Beauty".InZalta, Edward N.(ed.).Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Beautyat theIndiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- BBC Radio 4's In Our Time programme on Beauty(requiresRealAudio)

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas:Theories of Beauty to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- beautycheck.de/englishRegensburg University – Characteristics of beautiful faces

- Eli Siegel's "Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?"

- Art and love in Renaissance Italy,Issued in connection with an exhibition held Nov. 11, 2008-Feb. 16, 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (see Belle: Picturing Beautiful Women; pages 246–254).

- Plato - Symposiumin S. Marc Cohen, Patricia Curd, C. D. C. Reeve (ed.)