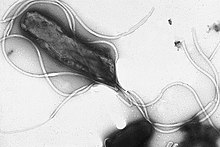

Helicobacter pylori,previously known asCampylobacter pylori,is agram-negative,flagellated,helical bacterium.Mutants can have a rod or curved rod shape that exhibits lessvirulence.[1][2]Itshelicalbody (from which thegenusnameHelicobacterderives) is thought to have evolved to penetrate themucous liningof thestomach,helped by itsflagella,and thereby establish infection.[3][2]The bacterium was first identified as the causal agent ofgastric ulcersin 1983 by Australianphysician-scientistsBarry MarshallandRobin Warren.[4][5]In 2005, they were awarded theNobel Prize in Physiology or Medicinefor their discovery.[6]

| Helicobacter pylori | |

|---|---|

| |

| Electron micrographofH. pyloripossessing multipleflagella(negative staining) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Campylobacterota |

| Class: | "Campylobacteria" |

| Order: | Campylobacterales |

| Family: | Helicobacteraceae |

| Genus: | Helicobacter |

| Species: | H. pylori

|

| Binomial name | |

| Helicobacter pylori (Marshallet al.1985) Goodwinet al.,1989

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Infection of the stomach withH. pyloriis not the cause of illness itself: over half of the global population is infected, but most individuals are asymptomatic.[7][8]Persistentcolonizationwith more virulent strains can induce a number of gastric and non-gastric disorders.[9]Gastric disorders due to infection begin withgastritis,or inflammation of the stomach lining.[10]When infection is persistent, the prolonged inflammation will becomechronic gastritis.Initially, this will be non-atrophic gastritis, but the damage caused to the stomach lining can bring about the development ofatrophic gastritisand ulcers within the stomach itself or theduodenum(the nearest part of the intestine).[10]At this stage, the risk of developinggastric canceris high.[11]However, the development of aduodenal ulcerconfers a comparatively lower risk of cancer.[12]Helicobacter pyloriis aclass 1 carcinogenic bacteria,and potential cancers include gastricMALT lymphomaandgastric cancer.[10][11]Infection withH. pyloriis responsible for an estimated 89% of all gastric cancers and is linked to the development of 5.5% of all cases cancers worldwide.[13][14]H. pyloriis the only bacterium known to cause cancer.[15]

Extragastric complications that have been linked toH. pyloriincludeanemiadue either to iron deficiency orvitamin B12 deficiency,diabetes mellitus,cardiovascular illness, and certain neurological disorders.[16]An inverse association has also been claimed withH. pylorihaving a positive protective effect againstasthma,esophageal cancer,inflammatory bowel disease(includinggastroesophageal reflux diseaseandCrohn's disease), and others.[16]

Some studies suggest thatH. pyloriplays an important role in the natural stomach ecology by influencing the type of bacteria that colonize the gastrointestinal tract.[17][18]Other studies suggest that non-pathogenic strains ofH. pylorimay beneficially normalize stomach acid secretion, and regulate appetite.[19]

In 2023, it was estimated that about two-thirds of the world's population was infected withH. pylori,being more common indeveloping countries.[20]The prevalence has declined in many countries due toeradication treatmentswith antibiotics andproton-pump inhibitors,and with increasedstandards of living.[21][22]

Microbiology

editHelicobacter pyloriis a species ofgram-negative bacteriain theHelicobactergenus.[23] About half the world's population is infected withH. pyloribut only a few strains arepathogenic.H pyloriis ahelical bacteriumhaving a predominantlyhelical shape,also often described as having a spiral orSshape.[24][25]Its helical shape is better suited for progressing through the viscousmucosa lining of the stomach,and is maintained by a number ofenzymesin thecell wall'speptidoglycan.[1]The bacteria reach the less acidic mucosa by use of theirflagella.[26]Three strains studied showed a variation in length from 2.8–3.3 μm but a fairly constant diameter of 0.55–0.58 μm.[24]H. pylorican convert from a helical to an inactivecoccoidform that can evade the immune system, and that may possibly become viable, known asviable but nonculturable(VBNC).[27][28]

Helicobacter pyloriismicroaerophilic– that is, it requiresoxygen,but at lower concentration than in theatmosphere.It contains ahydrogenasethat can produce energy by oxidizing molecularhydrogen(H2) made byintestinal bacteria.[29]

H. pylorican be demonstrated in tissue byGram stain,Giemsa stain,H&E stain,Warthin-Starry silver stain,acridine orange stain,andphase-contrast microscopy.It is capable of formingbiofilms.Biofilms help to hinder the action of antibiotics and can contribute to treatment failure.[30][31]

To successfully colonize its host,H. pyloriuses many differentvirulence factorsincludingoxidase,catalase,andurease.[32]Urease is the most abundant protein, its expression representing about 10% of the total protein weight.[33]

H. pyloripossesses five majorouter membrane proteinfamilies.[32]The largest family includes known and putativeadhesins.The other four families areporins,iron transporters,flagellum-associated proteins, and proteins of unknown function. Like other typical gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane ofH. pyloriconsists ofphospholipidsandlipopolysaccharide(LPS). TheO-antigenof LPS may befucosylatedand mimicLewis blood group antigensfound on the gastric epithelium.[32]

Genome

editHelicobacter pyloriconsists of a large diversity of strains, and hundreds ofgenomeshave been completelysequenced.[34][35][36]The genome of the strain26695consists of about 1.7 millionbase pairs,with some 1,576 genes.[37][38]Thepan-genome,that is the combined set of 30 sequenced strains, encodes 2,239 protein families (orthologous groupsOGs).[39]Among them, 1,248 OGs are conserved in all the 30 strains, and represent theuniversal core.The remaining 991 OGs correspond to theaccessory genomein which 277 OGs are unique to one strain.[40]

There are elevenrestriction modification systemsin the genome ofH. pylori.[38]This is an unusually high number providing adefence against bacteriophages.[38]

Transcriptome

editSingle-cell transcriptomicsusingsingle-cell RNA-Seqgave the completetranscriptomeofH. pyloriwhich was published in 2010. This analysis of itstranscriptionconfirmed the known acid induction of majorvirulenceloci, including the urease (ure) operon and the Cagpathogenicity island(PAI).[41]A total of 1,907transcription start sites337 primaryoperons,and 126 additional suboperons, and 66 monocistronswere identified. Until 2010, only about 55 transcription start sites (TSSs) were known in this species. 27% of the primary TSSs are also antisense TSSs, indicating that – similar toE. coli–antisense transcriptionoccurs across the entireH. pylorigenome. At least one antisense TSS is associated with about 46% of allopen reading frames,including manyhousekeeping genes.[41]About 50% of the5′UTRs(leader sequences) are 20–40 nucleotides (nt) in length and support the AAGGag motif located about 6 nt (median distance) upstream of start codons as the consensusShine–Dalgarno sequenceinH. pylori.[41]

Proteome

editTheproteomeofH. pylorihas been systematically analyzed and more than 70% of itsproteinshave been detected bymass spectrometry,and other methods. About 50% of the proteome has been quantified, informing of the number of protein copies in a typical cell.[42]

Studies of theinteractomehave identified more than 3000protein-protein interactions.This has provided information of how proteins interact with each other, either in stableprotein complexesor in more dynamic, transient interactions, which can help to identify the functions of the protein. This in turn helps researchers to find out what the function of uncharacterized proteins is, e.g. when an uncharacterized protein interacts with several proteins of theribosome(that is, it is likely also involved in ribosome function). About a third of all ~1,500 proteins inH. pyloriremain uncharacterized and their function is largely unknown.[43]

Infection

editAn infection withHelicobacter pylorican either have no symptoms even when lasting a lifetime, or can harm the stomach and duodenalliningsbyinflammatory responsesinduced by several mechanisms associated with a number ofvirulence factors.Colonizationcan initially causeH. pylori induced gastritis,aninflammation of the stomach liningthat became a listed disease inICD11.[44][45][46]This will progress tochronic gastritisif left untreated. Chronic gastritis may lead toatrophyof the stomach lining, and the development ofpeptic ulcers(gastric or duodenal). These changes may be seen as stages in the development ofgastric cancer,known asCorrea's cascade.[47][48]Extragastric complications that have been linked toH. pyloriincludeanemiadue either to iron-deficiency or vitamin B12 deficiency, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular, and certain neurological disorders.[16]

Peptic ulcers are a consequence of inflammation that allows stomach acid and the digestive enzymepepsinto overwhelm the protective mechanisms of themucous membranes.The location of colonization ofH. pylori,which affects the location of the ulcer, depends on the acidity of the stomach.[49]In people producing large amounts of acid,H. pyloricolonizes near thepyloric antrum(exit to the duodenum) to avoid the acid-secretingparietal cellsat thefundus(near the entrance to the stomach).[32]G cellsexpress relatively high levels ofPD-L1that protects these cells fromH. pylori-induced immune destruction.[50]In people producing normal or reduced amounts of acid,H. pylorican also colonize the rest of the stomach.

The inflammatory response caused by bacteria colonizing near the pyloric antrum induces G cells in the antrum to secrete the hormonegastrin,which travels through the bloodstream to parietal cells in the fundus.[51]Gastrin stimulates the parietal cells to secrete more acid into the stomach lumen, and over time increases the number of parietal cells, as well.[52]The increased acid load damages the duodenum, which may eventually lead to the formation of ulcers.

Helicobacter pyloriis a class Icarcinogen,and potential cancers include gastricmucosa-associated lymphoid tissue(MALT)lymphomasandgastric cancer.[10][11][53]Less commonly,diffuse large B-cell lymphomaof the stomach is a risk.[54]Infection withH. pyloriis responsible for around 89 per cent of all gastric cancers, and is linked to the development of 5.5 per cent of all cases of cancer worldwide.[13][14]Although the data varies between different countries, overall about 1% to 3% of people infected withHelicobacter pyloridevelop gastric cancer in their lifetime compared to 0.13% of individuals who have had noH. pyloriinfection.[55][32]H. pylori-induced gastric cancer is the third highest cause of worldwide cancer mortality as of 2018.[56]Because of the usual lack of symptoms, when gastric cancer is finally diagnosed it is often fairly advanced. More than half of gastric cancer patients have lymph node metastasis when they are initially diagnosed.[57]

Chronic inflammation that is a feature of cancer development is characterized by infiltration ofneutrophilsandmacrophagesto the gastric epithelium, which favors the accumulation ofpro-inflammatory cytokines,reactive oxygen species(ROS) andreactive nitrogen species(RNS) that causeDNA damage.[58]Theoxidative DNA damageand levels ofoxidative stresscan be indicated by a biomarker,8-oxo-dG.[58][59]Other damage to DNA includesdouble-strand breaks.[60]

Smallgastricandcolorectal polypsareadenomasthat are more commonly found in association with the mucosal damage induced byH. pylorigastritis.[61][62]Larger polyps can in time become cancerous.[63][61]A modest association ofH. pylorihas been made with the development ofcolorectal cancers,but as of 2020 causality had yet to be proved.[64][63]

Signs and symptoms

editMost people infected withH. pylorinever experience any symptoms or complications, but will have a 10% to 20% risk of developingpeptic ulcersor a 0.5% to 2% risk of stomach cancer.[8][65]H. pylori induced gastritismay present as acute gastritis withstomach ache,nausea,and ongoingdyspepsia(indigestion) that is sometimes accompanied by depression and anxiety.[8][66]Where the gastritis develops into chronic gastritis, or an ulcer, the symptoms are the same and can includeindigestion,stomach or abdominal pains, nausea,bloating,belching,feeling hunger in the morning, feeling full too soon, and sometimesvomiting,heartburn, bad breath, and weight loss.[67][68]

Complications of an ulcer can cause severe signs and symptoms such as black or tarry stool indicative ofbleedinginto the stomach or duodenum; blood - either red or coffee-ground colored in vomit; persistent sharp or severe abdominal pain; dizziness, and a fast heartbeat.[67][68]Bleeding is the most common complication. In cases caused byH. pylorithere was a greater need forhemostasisoften requiring gastric resection.[69]Prolonged bleeding may cause anemia leading to weakness and fatigue. Inflammation of the pyloric antrum, which connects the stomach to the duodenum, is more likely to lead to duodenal ulcers, while inflammation of thecorpusmay lead to a gastric ulcer.

Stomach cancercan cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, and unexplained weight loss.[70]Gastric polypsareadenomasthat are usually asymptomatic and benign, but may be the cause of dyspepsia, heartburn, bleeding from the stomach, and, rarely, gastric outlet obstruction.[61][71]Larger polyps may havebecome cancerous.[61] Colorectal polypsmay be the cause of rectal bleeding, anemia, constipation, diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain.[72]

Pathophysiology

editVirulence factorshelp a pathogen to evade the immune response of the host, and to successfullycolonize.The many virulence factors ofH. pyloriinclude its flagella, the production of urease, adhesins,serine proteaseHtrA(high temperature requirement A), and the majorexotoxinsCagAandVacA.[30][73]The presence of VacA and CagA are associated with moreadvanced outcomes.[74]CagA is an oncoprotein associated with the development of gastric cancer.[7]

H. pyloriinfection is associated withepigeneticallyreduced efficiency of theDNA repairmachinery, which favors the accumulation of mutations and genomic instability as well as gastric carcinogenesis.[75]It has been shown that expression of two DNA repair proteins,ERCC1andPMS2,was severely reduced onceH. pyloriinfection had progressed to causedyspepsia.[76]Dyspepsia occurs in about 20% of infected individuals.[77]Epigenetically reduced protein expression of DNA repair proteinsMLH1,MGMTandMRE11are also evident. Reduced DNA repair in the presence of increased DNA damage increases carcinogenic mutations and is likely a significant cause of gastric carcinogenesis.[59][78][79]Theseepigenetic alterationsare due toH. pylori-inducedmethylation of CpG sites in promoters of genes[78]andH. pylori-induced altered expression of multiplemicroRNAs.[79]

Two related mechanisms by whichH. pyloricould promote cancer have been proposed. One mechanism involves the enhanced production offree radicalsnearH. pyloriand an increased rate of host cellmutation.The other proposed mechanism has been called a "perigenetic pathway",[80]and involves enhancement of the transformed host cell phenotype by means of alterations in cell proteins, such asadhesionproteins.H. pylorihas been proposed to induce inflammation and locally high levels oftumor necrosis factor(TNF), also known as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)), and/orinterleukin 6(IL-6).[81]According to the proposed perigenetic mechanism, inflammation-associated signaling molecules, such as TNF, can alter gastric epithelial cell adhesion and lead to the dispersion and migration of mutated epithelial cells without the need for additional mutations intumor suppressor genes,such as genes that code for cell adhesion proteins.[82]

Flagellum

editThe first virulence factor ofHelicobacter pylorithat enables colonization is itsflagellum.[83]H. pylorihas from two to seven flagella atthe same polar locationwhich gives it a high motility. The flagellar filaments are about 3 μm long, and composed of two copolymerizedflagellins,FlaA and FlaB, coded by the genesflaA,andflaB.[26][73]The minor flagellin FlaB is located in the proximal region and the major flagellin FlaA makes up the rest of the flagellum.[84]The flagella are sheathed in a continuation of the bacterial outer membrane which gives protection against the gastric acidity. The sheath is also the location of the origin of the outer membrane vesicles that gives protection to the bacterium from bacteriophages.[84]

Flagella motility is provided by theproton motive forceprovided by urease-driven hydrolysis allowingchemotactic movementstowards the less acidicpHgradient in the mucosa.[30]The mucus layer is about 300μmthick, and the helical shape ofH. pyloriaided by its flagella helps it to burrow through this layer where it colonises a narrow region of about 25 μm closest to the epithelial cell layer, where the pH is near to neutral. They further colonise thegastric pitsand live in thegastric glands.[1][84][85]Occasionally the bacteria are found inside the epithelial cells themselves.[86]The use ofquorum sensingby the bacteria enables the formation of a biofilm which furthers persistent colonisation. In the layers of the biofilm,H. pylorican escape from the actions of antibiotics, and also be protected from host-immune responses.[87][88]In the biofilm,H. pylorican change the flagella to become adhesive structures.[89]

Urease

editIn addition to usingchemotaxisto avoid areas of high acidity (low pH),H. pylorialso produces large amounts ofurease,anenzymewhich breaks down theureapresent in the stomach to produceammoniaandbicarbonate,which are released into the bacterial cytosol and the surrounding environment, creating a neutral area.[90]The decreased acidity (higher pH) changes the mucus layer from a gel-like state to a more viscous state that makes it easier for the flagella to move the bacteria through the mucosa and attach to the gastric epithelial cells.[90]Helicobacter pyloriis one of the few known types of bacterium that has aurea cyclewhich is uniquely configured in the bacterium.[91]10% of the cell is ofnitrogen,a balance that needs to be maintained. Any excess is stored in urea excreted in the urea cycle.[91]

A final stage enzyme in the urea cycle isarginase,an enzyme that is crucial to the pathogenesis ofH. pylori.Arginase producesornithineand urea, which the enzyme urease breaks down into carbonic acid and ammonia. Urease is the bacterium’s most abundant protein, accounting for 10–15% of the bacterium's total protein content. Its expression is not only required for establishing initial colonization in the breakdown of urea to carbonic acid and ammonia, but is also essential for maintaining chronic infection.[92][65]Ammonia reduces stomach acidity, allowing the bacteria to become locally established. Arginase promotes the persistence of infection by consuming arginine; arginine is used by macrophages to produce nitric oxide, which has a strong antimicrobial effect.[91][93]The ammonia produced to regulatepHis toxic to epithelial cells.[94]

Adhesins

editH. pylorimust make attachment with the epithelial cells to prevent its being swept away with the constant movement and renewal of the mucus. To give them this adhesion,bacterial outer membrane proteinsas virulence factors calledadhesinsare produced.[95]BabA (blood group antigen binding adhesin) is most important during initial colonization, and SabA (sialic acid binding adhesin) is important in persistence. BabA attaches to glycans and mucins in the epithelium.[95]BabA (coded for by thebabA2gene) also binds to theLewis b antigendisplayed on the surface of the epithelial cells.[96]Adherence via BabA is acid sensitive and can be fully reversed by a decreased pH. It has been proposed that BabA's acid responsiveness enables adherence while also allowing an effective escape from an unfavorable environment such as a low pH that is harmful to the organism.[97]SabA (coded for by thesabAgene) binds to increased levels ofsialyl-LewisXantigen expressed on gastric mucosa.[98]

Cholesterol glucoside

editThe outer membrane containscholesterol glucoside,a sterol glucoside thatH. pyloriglycosylatesfrom thecholesterolin the gastric gland cells, and inserts it into its outer membrane.[99]This cholesterol glucoside is important for membrane stability, morphology and immune evasion, and is rarely found in other bacteria.[100][101]

The enzyme responsible for this ischolesteryl α-glucosyltransferase(αCgT or Cgt), encoded by theHP0421gene.[102]A major effect of the depletion of host cholesterol by Cgt is to disrupt cholesterol-richlipid raftsin the epithelial cells. Lipid rafts are involved in cell signalling and their disruption causes a reduction in the immune inflammatory response, particularly by reducinginterferon gamma.[103]Cgt is also secreted by the type IV secretion system, and is secreted in a selective way so that gastric niches where the pathogen can thrive are created.[102]Its lack has been shown to give vulnerability from environmental stress to bacteria, and also to disrupt CagA-mediated interactions.[99]

Catalase

editColonization induces an intense anti-inflammatory response as a first-line immune system defence. Phagocytic leukocytes and monocytes infiltrate the site of infection, and antibodies are produced.[104]H. pyloriis able to adhere to the surface of the phagocytes and impede their action. This is responded to by the phagocyte in the generation and release of oxygen metabolites into the surrounding space.H. pylorican survive this response by the activity ofcatalaseat its attachment to the phagocytic cell surface. Catalase decomposes hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, protecting the bacteria from toxicity. Catalase has been shown to almost completely inhibit the phagocytic oxidative response.[104]It is coded for by the genekatA.[105]

Tipα

editTNF-inducing protein alpha (Tipα) is a carcinogenic protein encoded byHP0596unique toH. pylorithat induces the expression oftumor necrosis factor.[82][106]Tipα enters gastric cancer cells where it binds to cell surfacenucleolin,and induces the expression ofvimentin.Vimentin is important in theepithelial–mesenchymal transitionassociated with the progression of tumors.[107]

CagA

editCagA(cytotoxin-associated antigen A) is a majorvirulence factorforH. pylori,anoncoproteinthat is encoded by thecagAgene. Bacterial strains with thecagAgene are associated with the ability to cause ulcers, MALT lymphomas, and gastric cancer.[108][109]ThecagAgene codes for a relatively long (1186-amino acid) protein. Thecagpathogenicity island(PAI) has about 30 genes, part of which code for a complextype IV secretion system(T4SS or TFSS). The lowGC-contentof thecagPAI relative to the rest of theHelicobactergenome suggests the island was acquired byhorizontal transferfrom another bacterial species.[38]Theserine proteaseHtrAalso plays a major role in the pathogenesis ofH. pylori.The HtrA protein enables the bacterium to transmigrate across the host cells' epithelium, and is also needed for the translocation of CagA.[110]

The virulence ofH. pylorimay be increased by genes of thecagpathogenicity island; about 50–70% ofH. pyloristrains in Western countries carry it.[111]Western people infected with strains carrying thecagPAI have a stronger inflammatory response in the stomach and are at a greater risk of developing peptic ulcers or stomach cancer than those infected with strains lacking the island.[32]Following attachment ofH. pylorito stomach epithelial cells, the type IV secretion system expressed by thecagPAI "injects" theinflammation-inducing agent, peptidoglycan, from their owncell wallsinto the epithelial cells. The injected peptidoglycan is recognized by the cytoplasmicpattern recognition receptor(immune sensor) Nod1, which then stimulates expression ofcytokinesthat promote inflammation.[112]

The type-IVsecretionapparatus also injects thecagPAI-encoded protein CagA into the stomach's epithelial cells, where it disrupts thecytoskeleton,adherence to adjacent cells, intracellular signaling,cell polarity,and other cellular activities.[113]Once inside the cell, the CagA protein isphosphorylatedontyrosine residuesby a host cell membrane-associatedtyrosine kinase(TK). CagA then allosterically activatesprotein tyrosine phosphatase/protooncogeneShp2.[114] These proteins are directly toxic to cells lining the stomach and signal strongly to the immune system that an invasion is under way. As a result of the bacterial presence, neutrophils and macrophages set up residence in the tissue to fight the bacteria assault.[115]Pathogenic strains ofH. pylorihave been shown to activate theepidermal growth factor receptor(EGFR), amembrane proteinwith a TKdomain.Activation of the EGFR byH. pyloriis associated with alteredsignal transductionandgene expressionin host epithelial cells that may contribute to pathogenesis. AC-terminalregion of the CagA protein (amino acids 873–1002) has also been suggested to be able to regulate host cellgene transcription,independent of protein tyrosine phosphorylation.[109]A great deal of diversity exists between strains ofH. pylori,and the strain that infects a person can predict the outcome.

VacA

editVacA(vacuolating cytotoxin autotransporter) is another major virulence factor encoded by thevacAgene.[116]All strains ofH. pyloricarry this gene but there is much diversity, and only 50% produce the encoded cytotoxin.[92][33]The four main subtypes ofvacAares1/m1, s1/m2, s2/m1,ands2/m2.s1/m1ands1/m2are known to cause an increased risk of gastric cancer.[117]VacA is an oligomeric protein complex that causes a progressive vacuolation in the epithelial cells leading to their death.[118]The vacuolation has also been associated with promoting intracellular reservoirs ofH. pyloriby disrupting the calcium channel cell membraneTRPML1.[119]VacA has been shown to increase the levels ofCOX2,an up-regulation that increases the production of aprostaglandinindicating a strong host cell inflammatory response.[118][120]

Outer membrane proteins and vesicles

editAbout 4% of the genome encodes forouter membrane proteinsthat can be grouped into five families.[121]The largest family includesbacterial adhesins.The other four families areporins,iron transporters,flagellum-associated proteins, and proteins of unknown function. Like other typical gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane ofH. pyloriconsists ofphospholipidsandlipopolysaccharide(LPS). TheO-antigenof LPS may befucosylatedand mimicLewis blood group antigensfound on the gastric epithelium.[32]

H. pyloriforms blebs from the outer membrane that pinch off asouter membrane vesiclesto provide an alternative delivery system for virulence factors including CagA.[99]

AHelicobactercysteine-rich proteinHcpA is known to trigger an immune response, causing inflammation.[122] AHelicobacter pylorivirulence factorDupAis associated with the development of duodenal ulcers.[123]

Mechanisms of tolerance

editThe need for survival has led to the development of different mechanisms of tolerance that enable the persistence ofH. pylori.[124]These mechanisms can also help to overcome the effects of antibiotics.[124]H. pylorihas to not only survive the harsh gastric acidity but also the sweeping of mucus by continuousperistalsis,andphagocyticattack accompanied by the release ofreactive oxygen species.[125]All organisms encode genetic programs for response to stressful conditions including those that cause DNA damage.[126]Stress conditions activate bacterial response mechanisms that are regulated by proteins expressed byregulator genes.[124]Theoxidative stresscan induce potentially lethal mutagenicDNA adductsin its genome. Surviving thisDNA damageis supported bytransformation-mediatedrecombinational repair,that contributes to successful colonization.[127][128]H. pyloriis naturally competent for transformation. While many organisms are competent only under certain environmental conditions, such as starvation,H. pyloriis competent throughout logarithmic growth.[126]

Transformation(the transfer of DNA from one bacterial cell to another through the intervening medium) appears to be part of an adaptation forDNA repair.[126]Homologous recombinationis required for repairingdouble-strand breaks(DSBs). The AddAB helicase-nuclease complex resects DSBs and loadsRecAonto single-strand DNA (ssDNA), which then mediates strand exchange, leading to homologous recombination and repair. The requirement of RecA plus AddAB for efficient gastric colonization suggests thatH. pyloriis either exposed to double-strand DNA damage that must be repaired or requires some other recombination-mediated event. In particular, natural transformation is increased by DNA damage inH. pylori,and a connection exists between the DNA damage response and DNA uptake inH. pylori.[126]This natural competence contributes to the persistence ofH. pylori.H. pylorihas much greater rates of recombination and mutation than other bacteria.[3]Genetically different strains can be found in the same host, and also in different regions of the stomach.[129]An overall response to multiple stressors can result from an interaction of the mechanisms.[124]

RuvABCproteins are essential to the process of recombinational repair, since they resolve intermediates in this process termedHolliday junctions.H. pylorimutants that are defective in RuvC have increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and to oxidative stress, exhibit reduced survival within macrophages, and are unable to establish successful infection in a mouse model.[130]Similarly, RecN protein plays an important role in DSB repair.[131]AnH. pylorirecN mutant displays an attenuated ability to colonize mouse stomachs, highlighting the importance of recombinational DNA repair in survival ofH. pyloriwithin its host.[131]

Biofilm

editAn effective sustained colonization response is the formation of abiofilm. Having first adhered to cellular surfaces, the bacteria produce and secreteextracellular polymeric substance(EPS). EPS consists largely ofbiopolymersand provides the framework for the biofilm structure.[90]H. pylorihelps the biofilm formation by altering its flagella into adhesive structures that provide adhesion between the cells.[89]Layers of aggregated bacteria as microcolonies accumulate to thicken the biofilm.

The matrix of EPS prevents the entry of antibiotics and immune cells, and provides protection from heat and competition from other microorganisms.[90]Channels form between the cells in the biofilm matrix allowing the transport of nutrients, enzymes, metabolites, and waste.[90]Cells in the deep layers may be nutritionally deprived and enter into the coccoid dormant-like state.[132][133]By changing the shape of the bacterium to a coccoid form, the exposure ofLPS(targeted by antibiotics) becomes limited, and so evades detection by the immune system.[134]It has also been shown that thecagpathogenicity island remains intact in the coccoid form.[134]Some of these antibiotic resistant cells may remain in the host aspersister cells.Following eradication, the persister cells can cause a recurrence of the infection.[132][133]Bacteria can detach from the biofilm to relocate and colonize elsewhere in the stomach to form other biofilms.[90]

Diagnosis

editColonization withH. pyloriis not a disease in itself, but a condition associated with a number ofstomach diseases.[32]Testing is recommended in cases ofpeptic ulcer diseaseor low-grade gastricMALT lymphoma;afterendoscopicresection of earlygastric cancer;for first-degree relatives with gastric cancer, and in certain cases of indigestion. Other indications that prompt testing forH. pyloriinclude long termaspirinor othernon-steroidal anti-inflammatoryuse, unexplainediron deficiency anemia,or in cases ofimmune thrombocytopenic purpura.[135]Several methods of testing exist, both invasive and non-invasive.

Non-invasive tests forH. pyloriinfection includeserological testsforantibodies,stool tests,andurea breath tests.Carbon urea breath tests include the use ofcarbon-13,or a radioactivecarbon-14producing a labelled carbon dioxide that can be detected in the breath.[136]Carbon urea breath tests have a highsensitivity and specificityfor the diagnosis ofH. pylori.[136]

Proton-pump inhibitors and antibiotics should be discontinued for at least 30 days prior to testing forH. pyloriinfection or eradication, as both agents inhibitH. pylorigrowth and may lead to false negative results.[135]Testing to confirm eradication is recommended 30 days or more after completion of treatment forH. pyloriinfection.H. pyloribreath testing or stool antigen testing are both reasonable tests to confirm eradication.[135]H. pyloriserologic testing, includingIgG antibodies,are not recommended as a test of eradication as they may remain elevated for years after successful treatment of infection.[135]

An endoscopic biopsy is an invasive means to test forH. pyloriinfection. Low-level infections can be missed by biopsy, so multiple samples are recommended. The most accurate method for detectingH. pyloriinfection is with ahistologicalexamination from two sites after endoscopicbiopsy,combined with either arapid urease testor microbial culture.[137]Generally, repeating endoscopy is not recommended to confirmH. pylorieradication, unless there are specific indications to repeat the procedure.[135]

Transmission

editHelicobacter pyloriis contagious, and istransmittedthrough direct contact either withsaliva(oral-oral) orfeces(fecal–oral route), but mainly through the oral–oral route.[8]Consistent with these transmission routes, the bacteria have been isolated fromfeces,saliva,anddental plaque.[138]H. pylorimay also be transmitted by consuming contaminated food or water.[139]Transmission occurs mainly within families in developed nations, but also from the broader community in developing countries.[140]

Prevention

editTo prevent the development ofH. pylori-related diseases when infection is suspected, antibiotic-based therapy regimens are recommended toeradicate the bacteria.[46]When successful the disease progression is halted. First line therapy is recommended if low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma is diagnosed, regardless of evidence ofH. pylori.However, if a severe condition of atrophic gastritis with gastric lesions is reached antibiotic-based treatment regimens are not advised since such lesions are often not reversible and will progress to gastric cancer.[46]If the cancer is managed to be treated it is advised that an eradication program be followed to prevent a recurrence of infection, or reduce a recurrence of the cancer, known as metachronous.[46][141][142]

Due toH. pylori'srole as a major cause of certain diseases (particularly cancers) and its consistently increasingresistance to antibiotic therapy,there is an obvious need for alternative treatments.[143]A vaccine targeted towards the development of gastric cancer, including MALT lymphoma, would also prevent the development of gastric ulcers.[5]A vaccine that would be prophylactic for use in children, and one that would be therapeutic later are the main goals. Challenges to this are the extreme genomic diversity shown byH. pyloriand complex host-immune responses.[143][144]

Previous studies in the Netherlands and in the US have shown that such a prophylactic vaccine programme would be ultimately cost-effective.[145][146]However, as of late 2019 there have been no advanced vaccine candidates and only one vaccine in a Phase I clinical trial. Furthermore, development of a vaccine againstH. pylorihas not been a priority of major pharmaceutical companies.[147]A key target for potential therapy is theproton-gated urea channel,since the secretion of urease enables the survival of the bacterium.[148]

Treatment

editThe 2022 Maastricht Consensus Report recognisedH. pylorigastritis asHelicobacter pylori induced gastritis,and has been included inICD11.[44][45][46]Initially the infection tends to be superficial, localised to the upper mucosal layers of the stomach.[149]The intensity of chronic inflammation is related to the cytotoxicity of theH. pyloristrain. A greater cytotoxicity will result in the change from a non-atrophic gastritis to an atrophic gastritis, with the loss ofmucous glands.This condition is a prequel to the development of peptic ulcers and gastric adenocarcinoma.[149]

Eradication ofH. pyloriis recommended to treat the infection, including when advanced topeptic ulcer disease.The recommendations for first-line treatment is a quadruple therapy consisting of aproton-pump inhibitor,amoxicillin,clarithromycin,andmetronidazole.Prior to treatment, testing is recommended to identify any pre-existing antibiotic resistances. A high rate of resistance to metronidazole has been observed. In areas of known clarithromycin resistance, the first-line therapy is changed to abismuthbased regimen includingtetracyclineand metronidazole for 14 days. If one of these courses of treatment fails, it is suggested to use the alternative.[44]

Treatment failure may typically be attributed to antibiotic resistance, or inadequate acid suppression from proton-pump inhibitors.[150]Following clinical trials, the use of thepotassium-competitive acid blockervonoprazan,which has a greater acid suppressive action, was approved for use in the US in 2022.[151][150]Its recommended use is in combination with amoxicillin, with or without clarithromycin. It has been shown to have a faster action and can be used with or without food.[150]Successful eradication regimens have revolutionised the treatment of peptic ulcers.[152][153]Eradication ofH. pyloriis also associated with a subsequent decreased risk of duodenal or gastric ulcer recurrence.[135]

Plant extractsandprobioticfoods are being increasingly used asadd-onsto usual treatments. Probiotic yogurts containinglactic acid bacteriaBifidobacteriaandLactobacillusexert a suppressive effect onH. pyloriinfection, and their use has been shown to improve the rates of eradication.[14]Some commensal intestinal bacteria as part of thegut microbiotaproducebutyratethat acts as aprebioticand enhances the mucosal immune barrier. Their use as probiotics may help balance the gut dysbiosis that accompanies antibiotic use.[154]Some probiotic strains have been shown to have bactericidal and bacteriostatic activity againstH. pylori,and also help to balance the gut dysbiosis.[155][134]Antibiotics have a negative impact on gastrointestinal microbiota and cause nausea, diarrhea, andsicknessfor which probiotics can alleviate.[134]

Antibiotic resistance

editIncreasingantibiotic resistanceis the main cause of initial treatment failure. Factors linked to resistance include mutations,efflux pumps,and the formation ofbiofilms.[156][157]One of the mainantibioticsused in eradication therapies isclarithromycin,but clarithromycin-resistant strains have become well-established and the use of alternative antibiotics needs to be considered. Fortunately, non-invasive stool tests for clarithromycin have become available that allow selection of patients that are likely to respond to the therapy.[158]Multidrug resistance has also increased.[157]Additional rounds of antibiotics or other therapies may be used.[159][160][161]Next generation sequencingis looked to for identifying initial specific antibiotic resistances that will help in targeting more effective treatment.[162]

In 2018, theWHOlistedH. pylorias a high priority pathogen for the research anddiscovery of new drugsand treatments.[163]The increasing antibiotic resistance encountered has spurred interest in developing alternative therapies using a number of plant compounds.[164][165]Plant compounds have fewer side effects than synthetic drugs. Most plant extracts contain a complex mix of components that may not act on their own as antimicrobials but can work together with antibiotics to enhance treatment and work towards overcoming resistance.[164]Plant compounds have a different mechanism of action that has proved useful in fighting antimicrobial resistance. For example, various compounds can act by inhibiting enzymes such as urease, and weakening adhesions to the mucous membrane.[166]Sulfur-containing compounds from plants with high concentrations of polysulfides,coumarins,andterpeneshave all been shown to be effective againstH. pylori.[164]

H. pyloriis found in saliva anddental plaque.Its transmission is known to include oral-oral, suggesting that the dental plaque biofilm may act as a reservoir for the bacteria. Periodontal therapy orscaling and root planinghas therefore been suggested as an additional treatment to enhance eradication rates, but more research is needed.[139][167]

Cancers

editStomach cancer

editHelicobacter pyloriis a risk factor forgastric adenocarcinomas.[168]Treatment is highly aggressive, with even localized disease being treated sequentially with chemotherapy and radiotherapy before surgical resection.[169]Since this cancer, once developed, is independent ofH. pyloriinfection, eradication regimens are not used.[170]

Gastric MALT lymphoma and DLBCL

editMALT lymphomasaremalignanciesofmucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.Early gastric MALTomas due toH. pylorimay be successfully treated (70–95% of cases) with one or moreeradication programs.[14]Some 50–80% of patients who experience eradication of the pathogen develop a remission and long-term clinical control of their lymphoma within 3–28 months.Radiation therapyto the stomach and surrounding (i.e. peri-gastric) lymph nodes has also been used to successfully treat these localized cases. Patients with non-localized (i.e. systemic Ann Arbor stage III and IV) disease who are free of symptoms have been treated withwatchful waitingor, if symptomatic, with theimmunotherapydrugrituximab(given for 4 weeks) combined with thechemotherapydrugchlorambucilfor 6–12 months; 58% of these patients attain a 58% progression-free survival rate at 5 years. Frail stage III/IV patients have been successfully treated with rituximab or the chemotherapy drugcyclophosphamidealone.[171]Antibiotic-proton pump inhibitor eradication therapy and localized radiation therapy have been used successfully to treat H. pylori-positive MALT lymphomas of the rectum; however radiation therapy has given slightly better results and therefore been suggested to be the disease's preferred treatment.[172]However, the generally recognized treatment of choice for patients with systemic involvement uses various chemotherapy drugs often combined with rituximab.

A MALT lymphoma may rarely transform into a more aggressivediffuse large B-cell lymphoma(DLBCL).[173]Where this is associated withH. pyloriinfection, the DLBCL is less aggressive and more amenable to treatment.[174][175][176]When limited to the stomach, they have sometimes been successfully treated withH. pylorieradication programs.[54][175][177][176]If unresponsive or showing a deterioration, a more conventional chemotherapy (CHOP), immunotherapy, or local radiotherapy can be considered, and any of these or a combination have successfully treated these more advanced types.[175][176]

Prognosis

editHelicobacter pyloricolonizes the stomach for decades in most people, and induces chronic gastritis, a long-lasting inflammation of the stomach. In most cases symptoms are never experienced but about 10–20% of those infected will ultimately develop gastric and duodenal ulcers, and have a possible 1–2% lifetime risk of gastric cancer.[65]

H. pylorithrives in a high salt diet, which is seen as an environmental risk factor for its association with gastric cancer. A diet high in salt enhances colonization, increases inflammation, increases the expression ofH. pylorivirulence factors, and intensifies chronic gastritis.[178][179]Paradoxically, extracts ofkimchi,a salted probiotic food, has been found to have a preventive effect onH. pylori–associated gastriccarcinogenesis.[180]

In the absence of treatment,H. pyloriinfection usually persists for life.[181]Infection may disappear in the elderly as the stomach's mucosa becomes increasingly atrophic and inhospitable to colonization. Some studies in young children up to two years of age have shown that infection can be transient in this age group.[182][183]

It is possible forH. pylorito re-establish in a person after eradication. This recurrence can be caused by the original strain (recrudescence), or be caused by a different strain (reinfection). A 2017 meta-analysis showed that the global per-person annual rates of recurrence, reinfection, and recrudescence is 4.3%, 3.1%, and 2.2% respectively. It is unclear what the main risk factors are.[184]

Mounting evidence suggestsH. pylorihas an important role in protection from some diseases.[16]The incidence ofacid reflux disease,Barrett's esophagus,andesophageal cancerhave been rising dramatically at the same time asH. pylori's presence decreases.[185]In 1996,Martin J. Blaseradvanced the hypothesis thatH. pylorihas a beneficial effect by regulating the acidity of the stomach contents.[51][185]The hypothesis is not universally accepted, as severalrandomized controlled trialsfailed to demonstrate worsening of acid reflux disease symptoms following eradication ofH. pylori.[186][187]Nevertheless, Blaser has reasserted his view thatH. pyloriis a member of the normalgastric microbiota.[17]He postulates that the changes in gastric physiology caused by the loss ofH. pyloriaccount for the recent increase in incidence of several diseases, includingtype 2 diabetes,obesity,and asthma.[17][188]His group has recently shown thatH. pyloricolonization is associated with a lowerincidenceof childhood asthma.[189]

Epidemiology

editIn 2023, it was estimated that about two-thirds of the world's population were infected withH. pyloriinfection, being more common indeveloping countries.[20]H. pyloriinfection is more prevalent in South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East.[153]The global prevalence declined markedly in the decade following 2010, with a particular reduction in Africa.[21]

The age when someone acquires this bacterium seems to influence the pathologic outcome of the infection. People infected at an early age are likely to develop more intense inflammation that may be followed by atrophic gastritis with a higher subsequent risk of gastric ulcer, gastric cancer, or both. Acquisition at an older age brings different gastric changes more likely to lead to duodenal ulcer.[181]Infections are usually acquired in early childhood in all countries.[32]However, the infection rate of children in developing nations is higher than inindustrialized nations,probably due to poor sanitary conditions, perhaps combined with lower antibiotics usage for unrelated pathologies. In developed nations, it is currently uncommon to find infected children, but the percentage of infected people increases with age. The higher prevalence among the elderly reflects higher infection rates incurred in childhood.[32]In the United States, prevalence appears higher inAfrican-AmericanandHispanicpopulations, most likely due to socioeconomic factors.[190][191]The lower rate of infection in the West is largely attributed to higher hygiene standards and widespread use of antibiotics. Despite high rates of infection in certain areas of the world, the overall frequency ofH. pyloriinfection is declining.[192]However, antibiotic resistance is appearing inH. pylori;many metronidazole- and clarithromycin-resistant strains are found in most parts of the world.[193]

History

editHelicobacter pylorimigrated out of Africaalong with its human host around 60,000 years ago.[194]Research has shown thatgenetic diversityinH. pylori,like that of its host, decreases with geographic distance fromEast Africa.Using the genetic diversity data, researchers have created simulations that indicate the bacteria seem to have spread from East Africa around 58,000 years ago. Their results indicate modern humans were already infected byH. pyloribefore their migrations out of Africa, and it has remained associated with human hosts since that time.[195]

H. pyloriwas first discovered in the stomachs of patients with gastritis andulcersin 1982 byBarry MarshallandRobin WarrenofPerth, Western Australia.At the time, the conventional thinking was that no bacterium could live in the acid environment of the human stomach. In recognition of their discovery, Marshall and Warren were awarded the 2005Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[196]

Before the research of Marshall and Warren, German scientists found spiral-shapedbacteriain the lining of the human stomach in 1875, but they were unable toculturethem, and the results were eventually forgotten.[185]The Italian researcherGiulio Bizzozerodescribed similarly shaped bacteria living in the acidic environment of the stomach of dogs in 1893.[197]ProfessorWalery Jaworskiof theJagiellonian UniversityinKrakówinvestigated sediments of gastric washings obtained bylavagefrom humans in 1899. Among some rod-like bacteria, he also found bacteria with a characteristic spiral shape, which he calledVibrio rugula.He was the first to suggest a possible role of this organism in the pathogenesis of gastric diseases. His work was included in theHandbook of Gastric Diseases,but it had little impact, as it was published only in Polish.[198]Several small studies conducted in the early 20th century demonstrated the presence of curved rods in the stomachs of many people with peptic ulcers and stomach cancers.[199]Interest in the bacteria waned, however, when an American study published in 1954 failed to observe the bacteria in 1180 stomach biopsies.[200]

Interest in understanding the role of bacteria in stomach diseases was rekindled in the 1970s, with the visualization of bacteria in the stomachs of people with gastric ulcers.[201]The bacteria had also been observed in 1979, by Robin Warren, who researched it further with Barry Marshall from 1981. After unsuccessful attempts at culturing the bacteria from the stomach, they finally succeeded in visualizing colonies in 1982, when they unintentionally left theirPetri dishesincubating for five days over theEasterweekend. In their original paper, Warren and Marshall contended that most stomach ulcers and gastritis were caused by bacterial infection and not bystressorspicy food,as had been assumed before.[202]

Some skepticism was expressed initially, but within a few years multiple research groups had verified the association ofH. pyloriwith gastritis and, to a lesser extent, ulcers.[203]To demonstrateH. pyloricaused gastritis and was not merely a bystander, Marshall drank a beaker ofH. pyloriculture. He became ill with nausea and vomiting several days later. An endoscopy 10 days after inoculation revealed signs of gastritis and the presence ofH. pylori.These results suggestedH. pyloriwas the causative agent. Marshall and Warren went on to demonstrate antibiotics are effective in the treatment of many cases of gastritis. In 1994, theNational Institutes of Healthstated most recurrent duodenal and gastric ulcers were caused byH. pylori,and recommended antibiotics be included in the treatment regimen.[204]

The bacterium was initially namedCampylobacter pyloridis,then renamedC. pyloriin 1987 (pyloribeing thegenitiveofpylorus,the circular opening leading from the stomach into the duodenum, from theAncient Greekwordπυλωρός,which meansgatekeeper[205]).[206]When16S ribosomal RNAgene sequencingand other research showed in 1989 that the bacterium did not belong in the genusCampylobacter,it was placed in its owngenus,Helicobacterfrom the Ancient Greekέλιξ(hělix) "spiral" or "coil".[205][207]

In October 1987, a group of experts met in Copenhagen to found the European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), an international multidisciplinary research group and the only institution focused onH. pylori.[208]The Group is involved with the Annual International Workshop on Helicobacter and Related Bacteria,[209](renamed as the European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group[210]), the Maastricht Consensus Reports (European Consensus on the management ofH. pylori),[211][212][213][214]and other educational and research projects, including two international long-term projects:

- European Registry onH. pyloriManagement (Hp-EuReg) – a database systematically registering the routine clinical practice of European gastroenterologists.[215]

- OptimalH. pylorimanagement in primary care (OptiCare) – a long-term educational project aiming to disseminate the evidence based recommendations of the Maastricht IV Consensus to primary care physicians in Europe, funded by an educational grant fromUnited European Gastroenterology.[216][217]

Research

editResults fromin vitrostudies suggest thatfatty acids,mainlypolyunsaturated fatty acids,have a bactericidal effect againstH. pylori,but theirin vivoeffects have not been proven.[218]

The antibiotic resistance provided by biofilms has generated much research into targeting the mechanisms ofquorum sensingused in the formation of biofilms.[88]

A suitable vaccine forH. pylori,either prophylactic or therapeutic, is an ongoing research aim.[8]TheMurdoch Children's Research Instituteis working at developing a vaccine that instead of specifically targeting the bacteria, aims to inhibit the inflammation caused that leads to the associated diseases.[147]

Gastric organoidscan be used as models for the study ofH. pyloripathogenesis.[95]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^abcMartínez LE, O'Brien VP, Leverich CK, Knoblaugh SE, Salama NR (July 2019)."Nonhelical Helicobacter pylori Mutants Show Altered Gland Colonization and Elicit Less Gastric Pathology than Helical Bacteria during Chronic Infection".Infect Immun.87(7).doi:10.1128/IAI.00904-18.PMC6589060.PMID31061142.

- ^abSalama NR (April 2020)."Cell morphology as a virulence determinant: lessons from Helicobacter pylori".Curr Opin Microbiol.54:11–17.doi:10.1016/j.mib.2019.12.002.PMC7247928.PMID32014717.

- ^abRust M, Schweinitzer T, Josenhans C (2008)."Helicobacter Flagella, Motility and Chemotaxis".In Yamaoka, Y. (ed.).Helicobacter pylori:Molecular Genetics and Cellular Biology.Caister Academic Press.ISBN978-1-904455-31-8.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2016.Retrieved1 April2008.

- ^Warren JR, Marshall B (June 1983). "Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis".Lancet.1(8336): 1273–5.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92719-8.PMID6134060.S2CID1641856.

- ^abFitzGerald R, Smith SM (2021). "An Overview of Helicobacter pylori Infection".Helicobacter Pylori.Methods Mol Biol. Vol. 2283. pp. 1–14.doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-1302-3_1.ISBN978-1-0716-1301-6.PMID33765303.S2CID232365068.

- ^Watts G (October 2005)."Nobel prize is awarded to doctors who discovered H pylori".BMJ.331(7520): 795.doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7520.795.PMC1246068.PMID16210262.

- ^ab"Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and Cancer - NCI".www.cancer.gov.25 September 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2023.Retrieved18 October2023.

- ^abcdede Brito BB, da Silva FA, Soares AS, Pereira VA, Santos ML, Sampaio MM, et al. (October 2019)."Pathogenesis and clinical management of Helicobacter pylori gastric infection".World J Gastroenterol.25(37): 5578–5589.doi:10.3748/wjg.v25.i37.5578.PMC6785516.PMID31602159.

- ^Chen CC, Liou JM, Lee YC, Hong TC, El-Omar EM, Wu MS (2021)."The interplay between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal microbiota".Gut Microbes.13(1): 1–22.doi:10.1080/19490976.2021.1909459.PMC8096336.PMID33938378.

- ^abcdMatsuo Y, Kido Y, Yamaoka Y (March 2017)."Helicobacter pylori Outer Membrane Protein-Related Pathogenesis".Toxins.9(3): 101.doi:10.3390/toxins9030101.PMC5371856.PMID28287480.

- ^abcMarghalani AM, Bin Salman TO, Faqeeh FJ, Asiri MK, Kabel AM (June 2020)."Gastric carcinoma: Insights into risk factors, methods of diagnosis, possible lines of management, and the role of primary care".J Family Med Prim Care.9(6): 2659–2663.doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_527_20.PMC7491774.PMID32984103.

- ^Koga Y (December 2022)."Microbiota in the stomach and application of probiotics to gastroduodenal diseases".World J Gastroenterol.28(47): 6702–6715.doi:10.3748/wjg.v28.i47.6702.PMC9813937.PMID36620346.

- ^abShin WS, Xie F, Chen B, Yu J, Lo KW, Tse GM, et al. (October 2023)."Exploring the Microbiome in Gastric Cancer: Assessing Potential Implications and Contextualizing Microorganisms beyond H. pylori and Epstein-Barr Virus".Cancers.15(20): 4993.doi:10.3390/cancers15204993.PMC10605912.PMID37894360.

- ^abcdVioleta Filip P, Cuciureanu D, Sorina Diaconu L, Maria Vladareanu A, Silvia Pop C (2018)."MALT lymphoma: epidemiology, clinical diagnosis and treatment".Journal of Medicine and Life.11(3): 187–193.doi:10.25122/jml-2018-0035.PMC6197515.PMID30364585.

- ^Ruggiero P (November 2014)."Use of probiotics in the fight against Helicobacter pylori".World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol.5(4): 384–91.doi:10.4291/wjgp.v5.i4.384.PMC4231502.PMID25400981.

- ^abcdSantos ML, de Brito BB, da Silva FA, Sampaio MM, Marques HS, Oliveira E, et al. (July 2020)."Helicobacter pylori infection: Beyond gastric manifestations".World J Gastroenterol.26(28): 4076–4093.doi:10.3748/wjg.v26.i28.4076.PMC7403793.PMID32821071.

- ^abcBlaser MJ (October 2006)."Who are we? Indigenous microbes and the ecology of human diseases".EMBO Reports.7(10): 956–60.doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400812.PMC1618379.PMID17016449.

- ^Gravina AG, Zagari RM, De Musis C, Romano L, Loguercio C, Romano M (August 2018)."Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases: A review".World Journal of Gastroenterology(Review).24(29): 3204–3221.doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i29.3204.PMC6079286.PMID30090002.

- ^Ackerman J (June 2012). "The ultimate social network".Scientific American.Vol. 306, no. 6. pp. 36–43.doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0612-36.PMID22649992.

- ^ab"Helicobacter pylori | CDC Yellow Book 2024".wwwnc.cdc.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 22 October 2023.Retrieved20 October2023.

- ^abLi Y, Choi H, Leung K, Jiang F, Graham DY, Leung WK (19 April 2023). "Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection between 1980 and 2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis".The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.8(6): 553–564.doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00070-5.PMID37086739.S2CID258272798.

- ^Hooi JK, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MM, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, et al. (August 2017)."Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis".Gastroenterology.153(2): 420–429.doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022.PMID28456631.

- ^Goodwin CS, Armstrong JA, Chilvers T, et al. (1989)."Transfer ofCampylobacter pyloriandCampylobacter mustelaetoHelicobactergen. nov. asHelicobacter pyloricomb. nov. andHelicobacter mustelaecomb. nov., respectively ".Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol.39(4): 397–405.doi:10.1099/00207713-39-4-397.

- ^abMartínez LE, Hardcastle JM, Wang J, Pincus Z, Tsang J, Hoover TR, et al. (January 2016)."Helicobacter pylori strains vary cell shape and flagellum number to maintain robust motility in viscous environments".Mol Microbiol.99(1): 88–110.doi:10.1111/mmi.13218.PMC4857613.PMID26365708.

- ^O'Rourke J, Bode G (2001).Morphology and Ultrastructure.ASM Press.ISBN978-1-55581-213-3.PMID21290748.

- ^abKao CY, Sheu BS, Wu JJ (February 2016)."Helicobacter pylori infection: An overview of bacterial virulence factors and pathogenesis".Biomedical Journal.39(1): 14–23.doi:10.1016/j.bj.2015.06.002.PMC6138426.PMID27105595.

- ^Ierardi E, Losurdo G, Mileti A, Paolillo R, Giorgio F, Principi M, et al. (May 2020)."The Puzzle of Coccoid Forms of Helicobacter pylori: Beyond Basic Science".Antibiotics.9(6): 293.doi:10.3390/antibiotics9060293.PMC7345126.PMID32486473.

- ^Luo Q, Liu N, Pu S, Zhuang Z, Gong H, Zhang D (2023)."A review on the research progress on non-pharmacological therapy of Helicobacter pylori".Front Microbiol.14:1134254.doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1134254.PMC10063898.PMID37007498.

- ^Olson JW, Maier RJ (November 2002). "Molecular hydrogen as an energy source for Helicobacter pylori".Science.298(5599): 1788–90.Bibcode:2002Sci...298.1788O.doi:10.1126/science.1077123.PMID12459589.S2CID27205768.

- ^abcBaj J, Forma A, Sitarz M, Portincasa P, Garruti G, Krasowska D, et al. (December 2020)."Helicobacter pylori Virulence Factors-Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogenicity in the Gastric Microenvironment".Cells.10(1): 27.doi:10.3390/cells10010027.PMC7824444.PMID33375694.

- ^Elshenawi Y, Hu S, Hathroubi S (July 2023)."Biofilm of Helicobacter pylori: Life Cycle, Features, and Treatment Options".Antibiotics.12(8): 1260.doi:10.3390/antibiotics12081260.PMC10451559.PMID37627679.

- ^abcdefghijKusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ (July 2006)."Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection".Clinical Microbiology Reviews.19(3): 449–90.doi:10.1128/CMR.00054-05.PMC1539101.PMID16847081.

- ^abAlzahrani S, Lina TT, Gonzalez J, Pinchuk IV, Beswick EJ, Reyes VE (September 2014)."Effect of Helicobacter pylori on gastric epithelial cells".World J Gastroenterol.20(36): 12767–80.doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12767.PMC4177462.PMID25278677.

- ^"Genome information for theH. pylori26695 and J99 strains ".Institut Pasteur. 2002.Archivedfrom the original on 26 November 2017.Retrieved1 September2008.

- ^"Helicobacter pyloriJ99, complete genome ".National Center for Biotechnology Information.Archivedfrom the original on 6 April 2011.Retrieved1 September2008.

- ^Oh JD, Kling-Bäckhed H, Giannakis M, Xu J, Fulton RS, Fulton LA, et al. (June 2006)."The complete genome sequence of a chronic atrophic gastritis Helicobacter pylori strain: evolution during disease progression".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.103(26): 9999–10004.Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.9999O.doi:10.1073/pnas.0603784103.PMC1480403.PMID16788065.

- ^"Helicobacter pylori 26695 genome assembly ASM30779v1".NCBI.Retrieved4 June2024.

- ^abcdTomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, et al. (August 1997)."The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori".Nature.388(6642): 539–47.Bibcode:1997Natur.388..539T.doi:10.1038/41483.PMID9252185.S2CID4411220.

- ^van Vliet AH (January 2017)."Use of pan-genome analysis for the identification of lineage-specific genes of Helicobacter pylori".FEMS Microbiology Letters.364(2): fnw296.doi:10.1093/femsle/fnw296.PMID28011701.

- ^Uchiyama I, Albritton J, Fukuyo M, Kojima KK, Yahara K, Kobayashi I (9 August 2016)."A Novel Approach to Helicobacter pylori Pan-Genome Analysis for Identification of Genomic Islands".PLOS ONE.11(8): e0159419.Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1159419U.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159419.PMC4978471.PMID27504980.

- ^abcSharma CM, Hoffmann S, Darfeuille F, Reignier J, Findeiss S, Sittka A, et al. (March 2010). "The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori".Nature.464(7286): 250–5.Bibcode:2010Natur.464..250S.doi:10.1038/nature08756.PMID20164839.S2CID205219639.

- ^Müller SA, Pernitzsch SR, Haange SB, Uetz P, von Bergen M, Sharma CM, et al. (3 August 2015)."Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture based proteomics reveals differences in protein abundances between spiral and coccoid forms of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori".Journal of Proteomics.126:34–45.doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2015.05.011.ISSN1874-3919.PMID25979772.S2CID415255.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2021.Retrieved26 July2021.

- ^Wuchty S, Müller SA, Caufield JH, Häuser R, Aloy P, Kalkhof S, et al. (May 2018)."Proteome Data Improves Protein Function Prediction in the Interactome of Helicobacter pylori".Mol Cell Proteomics.17(5): 961–973.doi:10.1074/mcp.RA117.000474.PMC5930399.PMID29414760.

- ^abcMalfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, et al. (August 2022). "Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report".Gut.71(9): 1724–1762.doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327745.hdl:10486/714546.PMID35944925.

- ^ab"ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics".icd.who.int.Archivedfrom the original on 15 October 2023.Retrieved9 January2024.

- ^abcde"The Changes Made in the New Expert Consensus on H pylori".Medscape.Archivedfrom the original on 9 January 2024.Retrieved9 January2024.

- ^Repetto O, Vettori R, Steffan A, Cannizzaro R, De Re V (November 2023)."Circulating Proteins as Diagnostic Markers in Gastric Cancer".Int J Mol Sci.24(23): 16931.doi:10.3390/ijms242316931.PMC10706891.PMID38069253.

- ^Livzan MA, Mozgovoi SI, Gaus OV, Shimanskaya AG, Kononov AV (July 2023)."Histopathological Evaluation of Gastric Mucosal Atrophy for Predicting Gastric Cancer Risk: Problems and Solutions".Diagnostics.13(15): 2478.doi:10.3390/diagnostics13152478.PMC10417051.PMID37568841.

- ^Dixon MF (February 2000). "Patterns of inflammation linked to ulcer disease".Baillière's Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology.14(1): 27–40.doi:10.1053/bega.1999.0057.PMID10749087.

- ^Mommersteeg MC, Yu BT, van den Bosch TP, von der Thüsen JH, Kuipers EJ, Doukas M, et al. (October 2022)."Constitutive programmed death ligand 1 expression protects gastric G-cells from Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation".Helicobacter.27(5): e12917.doi:10.1111/hel.12917.PMC9542424.PMID35899973.S2CID251132578.

- ^abBlaser MJ, Atherton JC (February 2004)."Helicobacter pylori persistence: biology and disease".The Journal of Clinical Investigation.113(3): 321–33.doi:10.1172/JCI20925.PMC324548.PMID14755326.

- ^Schubert ML, Peura DA (June 2008). "Control of gastric acid secretion in health and disease".Gastroenterology.134(7): 1842–60.doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.021.PMID18474247.S2CID206210451.

- ^Abbas H, Niazi M, Makker J (May 2017)."Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma of the Colon: A Case Report and a Literature Review".The American Journal of Case Reports.18:491–497.doi:10.12659/AJCR.902843.PMC5424574.PMID28469125.

- ^abPaydas S (April 2015)."Helicobacter pylori eradication in gastric diffuse large B cell lymphoma".World Journal of Gastroenterology.21(13): 3773–6.doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i13.3773.PMC4385524.PMID25852262.

- ^Kuipers EJ (March 1999). "Review article: exploring the link between Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer".Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.13(Suppl 1): 3–11.doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00002.x.PMID10209681.S2CID19231673.

- ^Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, et al. (April 2019)."Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods".International Journal of Cancer.144(8): 1941–1953.doi:10.1002/ijc.31937.PMID30350310.

- ^Deng JY, Liang H (April 2014)."Clinical significance of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer".World Journal of Gastroenterology.20(14): 3967–75.doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.3967.PMC3983452.PMID24744586.

- ^abValenzuela MA, Canales J, Corvalán AH, Quest AF (December 2015)."Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation and epigenetic changes during gastric carcinogenesis".World Journal of Gastroenterology.21(45): 12742–56.doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12742.PMC4671030.PMID26668499.

- ^abRaza Y, Khan A, Farooqui A, Mubarak M, Facista A, Akhtar SS, et al. (October 2014). "Oxidative DNA damage as a potential early biomarker of Helicobacter pylori associated carcinogenesis".Pathology & Oncology Research.20(4): 839–46.doi:10.1007/s12253-014-9762-1.PMID24664859.S2CID18727504.

- ^Koeppel M, Garcia-Alcalde F, Glowinski F, Schlaermann P, Meyer TF (June 2015)."Helicobacter pylori Infection Causes Characteristic DNA Damage Patterns in Human Cells".Cell Reports.11(11): 1703–13.doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.030.PMID26074077.

- ^abcdMarkowski AR, Markowska A, Guzinska-Ustymowicz K (October 2016)."Pathophysiological and clinical aspects of gastric hyperplastic polyps".World Journal of Gastroenterology.22(40): 8883–8891.doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.8883.PMC5083793.PMID27833379.

- ^Dong YF, Guo T, Yang H, Qian JM, Li JN (February 2019). "[Correlations between gastric Helicobacter pylori infection and colorectal polyps or cancer]".Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi(in Chinese).58(2): 139–142.doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2019.02.011.PMID30704201.

- ^abZuo Y, Jing Z, Bie M, Xu C, Hao X, Wang B (September 2020)."Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis".Medicine (Baltimore).99(37): e21832.doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000021832.PMC7489651.PMID32925719.

- ^Papastergiou V, Karatapanis S, Georgopoulos SD (January 2016)."Helicobacter pylori and colorectal neoplasia: Is there a causal link?".World J Gastroenterol.22(2): 649–58.doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.649.PMC4716066.PMID26811614.

- ^abcDebowski AW, Walton SM, Chua EG, Tay AC, Liao T, Lamichhane B, et al. (June 2017)."Helicobacter pylori gene silencing in vivo demonstrates urease is essential for chronic infection".PLOS Pathogens.13(6): e1006464.doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006464.PMC5500380.PMID28644872.

- ^Al Quraan AM, Beriwal N, Sangay P, Namgyal T (October 2019)."The Psychotic Impact of Helicobacter pylori Gastritis and Functional Dyspepsia on Depression: A Systematic Review".Cureus.11(10): e5956.doi:10.7759/cureus.5956.PMC6863582.PMID31799095.

- ^ab"Helicobacter Pylori (H. Pylori) Tests: MedlinePlus Medical Test".medlineplus.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 16 February 2024.Retrieved16 February2024.

- ^ab"Symptoms & Causes of Peptic Ulcers (Stomach or Duodenal Ulcers) - NIDDK".National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.Archivedfrom the original on 17 February 2024.Retrieved17 February2024.

- ^Popa DG, Obleagă CV, Socea B, Serban D, Ciurea ME, Diaconescu M, et al. (October 2021)."Role of Helicobacter pylori in the triggering and evolution of hemorrhagic gastro-duodenal lesions".Exp Ther Med.22(4): 1147.doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10582.PMC8392874.PMID34504592.

- ^Al-Azri M, Al-Kindi J, Al-Harthi T, Al-Dahri M, Panchatcharam SM, Al-Maniri A (June 2019)."Awareness of Stomach and Colorectal Cancer Risk Factors, Symptoms and Time Taken to Seek Medical Help Among Public Attending Primary Care Setting in Muscat Governorate, Oman".Journal of Cancer Education.34(3): 423–434.doi:10.1007/s13187-017-1266-8.ISSN0885-8195.PMID28782080.S2CID4017466.Archivedfrom the original on 24 February 2024.Retrieved20 January2024.

- ^Wu Q, Yang ZP, Xu P, Gao LC, Fan DM (July 2013). "Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis".Colorectal Disease.15(7): e352-64.doi:10.1111/codi.12284.PMID23672575.S2CID5444584.

- ^Soetikno RM, Kaltenbach T, Rouse RV, Park W, Maheshwari A, Sato T, et al. (March 2008)."Prevalence of nonpolypoid (flat and depressed) colorectal neoplasms in asymptomatic and symptomatic adults".JAMA.299(9): 1027–35.doi:10.1001/jama.299.9.1027.PMID18319413.

- ^abYamaoka Y, Saruuljavkhlan B, Alfaray RI, Linz B (2023). "Pathogenomics of Helicobacter pylori".Helicobacter pylori and Gastric Cancer.Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 444. pp. 117–155.doi:10.1007/978-3-031-47331-9_5.ISBN978-3-031-47330-2.PMID38231217.

- ^Alfarouk KO, Bashir AH, Aljarbou AN, Ramadan AM, Muddathir AK, AlHoufie ST, et al. (22 February 2019)."Helicobacter pylori in Gastric Cancer and Its Management".Frontiers in Oncology.9:75.doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00075.PMC6395443.PMID30854333.

- ^Santos JC, Ribeiro ML (August 2015)."Epigenetic regulation of DNA repair machinery in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis".World Journal of Gastroenterology.21(30): 9021–37.doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i30.9021.PMC4533035.PMID26290630.

- ^Raza Y, Ahmed A, Khan A, Chishti AA, Akhter SS, Mubarak M, et al. (May 2020)."Helicobacter pylori severely reduces expression of DNA repair proteins PMS2 and ERCC1 in gastritis and gastric cancer".DNA Repair.89:102836.doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2020.102836.PMID32143126.

- ^Dore MP, Pes GM, Bassotti G, Usai-Satta P (2016)."Dyspepsia: When and How to Test for Helicobacter pylori Infection".Gastroenterology Research and Practice.2016:8463614.doi:10.1155/2016/8463614.PMC4864555.PMID27239194.

- ^abMuhammad JS, Eladl MA, Khoder G (February 2019)."Helicobacter pylori-induced DNA Methylation as an Epigenetic Modulator of Gastric Cancer: Recent Outcomes and Future Direction".Pathogens.8(1): 23.doi:10.3390/pathogens8010023.PMC6471032.PMID30781778.

- ^abNoto JM, Peek RM (2011)."The role of microRNAs in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis and gastric carcinogenesis".Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology.1:21.doi:10.3389/fcimb.2011.00021.PMC3417373.PMID22919587.

- ^Tsuji S, Kawai N, Tsujii M, Kawano S, Hori M (July 2003)."Review article: inflammation-related promotion of gastrointestinal carcinogenesis--a perigenetic pathway".Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.18(Suppl 1): 82–9.doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.18.s1.22.x.PMID12925144.S2CID22646916.

- ^Yu B, de Vos D, Guo X, Peng S, Xie W, Peppelenbosch MP, et al. (April 2024)."IL-6 facilitates cross-talk between epithelial cells and tumor- associated macrophages in Helicobacter pylori-linked gastric carcinogenesis".Neoplasia.50:100981.doi:10.1016/j.neo.2024.100981.PMC10912637.PMID38422751.

- ^abSuganuma M, Yamaguchi K, Ono Y, Matsumoto H, Hayashi T, Ogawa T, et al. (July 2008)."TNF-alpha-inducing protein, a carcinogenic factor secreted from H. pylori, enters gastric cancer cells".International Journal of Cancer.123(1): 117–22.doi:10.1002/ijc.23484.PMID18412243.S2CID5532769.

- ^Duan Q, Zhou M, Zhu L, Zhu G (January 2013). "Flagella and bacterial pathogenicity".J Basic Microbiol.53(1): 1–8.doi:10.1002/jobm.201100335.PMID22359233.S2CID22002199.

- ^abcNedeljković M, Sastre DE, Sundberg EJ (July 2021)."Bacterial Flagellar Filament: A Supramolecular Multifunctional Nanostructure".Int J Mol Sci.22(14): 7521.doi:10.3390/ijms22147521.PMC8306008.PMID34299141.

- ^Elbehiry A, Marzouk E, Aldubaib M, Abalkhail A, Anagreyyah S, Anajirih N, et al. (January 2023)."Helicobacter pylori Infection: Current Status and Future Prospects on Diagnostic, Therapeutic and Control Challenges".Antibiotics.12(2): 191.doi:10.3390/antibiotics12020191.PMC9952126.PMID36830102.

- ^Petersen AM, Krogfelt KA (May 2003)."Helicobacter pylori: an invading microorganism? A review".FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology(Review).36(3): 117–26.doi:10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00020-8.PMID12738380.

- ^Ali A, AlHussaini KI (January 2024)."Helicobacter pylori: A Contemporary Perspective on Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies".Microorganisms.12(1): 222.doi:10.3390/microorganisms12010222.PMC10818838.PMID38276207.

- ^abZafer MM, Mohamed GA, Ibrahim SR, Ghosh S, Bornman C, Elfaky MA (February 2024)."Biofilm-mediated infections by multidrug-resistant microbes: a comprehensive exploration and forward perspectives".Arch Microbiol.206(3): 101.Bibcode:2024ArMic.206..101Z.doi:10.1007/s00203-023-03826-z.PMC10867068.PMID38353831.

- ^abSun Q, Yuan C, Zhou S, Lu J, Zeng M, Cai X, et al. (2023)."Helicobacter pylori infection: a dynamic process from diagnosis to treatment".Front Cell Infect Microbiol.13:1257817.doi:10.3389/fcimb.2023.1257817.PMC10621068.PMID37928189.

- ^abcdefLin Q, Lin S, Fan Z, Liu J, Ye D, Guo P (May 2024)."A Review of the Mechanisms of Bacterial Colonization of the Mammal Gut".Microorganisms.12(5): 1026.doi:10.3390/microorganisms12051026.PMC11124445.PMID38792855.

- ^abcHernández VM, Arteaga A, Dunn MF (November 2021). "Diversity, properties and functions of bacterial arginases".FEMS Microbiol Rev.45(6).doi:10.1093/femsre/fuab034.PMID34160574.

- ^abLi S, Zhao W, Xia L, Kong L, Yang L (2023)."How Long Will It Take to Launch an Effective Helicobacter pylori Vaccine for Humans?".Infect Drug Resist.16:3787–3805.doi:10.2147/IDR.S412361.PMC10278649.PMID37342435.

- ^George G, Kombrabail M, Raninga N, Sau AK (March 2017)."Arginase of Helicobacter Gastric Pathogens Uses a Unique Set of Non-catalytic Residues for Catalysis".Biophysical Journal.112(6): 1120–1134.Bibcode:2017BpJ...112.1120G.doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2017.02.009.PMC5376119.PMID28355540.

- ^Smoot DT (December 1997)."How does Helicobacter pylori cause mucosal damage? Direct mechanisms".Gastroenterology.113(6 Suppl): S31-4, discussion S50.doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(97)80008-X.PMID9394757.

- ^abcDoohan D, Rezkitha YA, Waskito LA, Yamaoka Y, Miftahussurur M (July 2021)."Helicobacter pylori BabA-SabA Key Roles in the Adherence Phase: The Synergic Mechanism for Successful Colonization and Disease Development".Toxins.13(7): 485.doi:10.3390/toxins13070485.PMC8310295.PMID34357957.

- ^Rad R, Gerhard M, Lang R, Schöniger M, Rösch T, Schepp W, et al. (15 March 2002)."The Helicobacter pylori Blood Group Antigen-Binding Adhesin Facilitates Bacterial Colonization and Augments a Nonspecific Immune Response".The Journal of Immunology.168(6): 3033–3041.doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.3033.PMID11884476.

- ^Bugaytsova JA, Björnham O, Chernov YA, Gideonsson P, Henriksson S, Mendez M, et al. (March 2017)."Helicobacter pylori Adapts to Chronic Infection and Gastric Disease via pH-Responsive BabA-Mediated Adherence".Cell Host & Microbe.21(3): 376–389.doi:10.1016/j.chom.2017.02.013.PMC5392239.PMID28279347.

- ^Mahdavi J, Sondén B, Hurtig M, Olfat FO, Forsberg L, Roche N, et al. (July 2002)."Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation".Science.297(5581): 573–8.Bibcode:2002Sci...297..573M.doi:10.1126/science.1069076.PMC2570540.PMID12142529.

- ^abcTesterman TL, Morris J (September 2014)."Beyond the stomach: an updated view of Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment".World Journal of Gastroenterology(Review).20(36): 12781–808.doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12781.PMC4177463.PMID25278678.

- ^Zhang L, Xie J (September 2023)."Biosynthesis, structure and biological function of cholesterol glucoside in Helicobacter pylori: A review".Medicine (Baltimore).102(36): e34911.doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000034911.PMC10489377.PMID37682174.

- ^Ridyard KE, Overhage J (May 2021)."The Potential of Human Peptide LL-37 as an Antimicrobial and Anti-Biofilm Agent".Antibiotics.10(6): 650.doi:10.3390/antibiotics10060650.PMC8227053.PMID34072318.

- ^abHsu CY, Yeh JY, Chen CY, Wu HY, Chiang MH, Wu CL, et al. (December 2021)."Helicobacter pylori cholesterol-α-glucosyltransferase manipulates cholesterol for bacterial adherence to gastric epithelial cells".Virulence.12(1): 2341–2351.doi:10.1080/21505594.2021.1969171.PMC8437457.PMID34506250.