Comparative anatomyis the study of similarities and differences in theanatomyof differentspecies.It is closely related toevolutionary biologyandphylogeny[1](theevolutionof species).

The science began in theclassical era,continuing in theearly modern periodwith work byPierre Belonwho noted the similarities of the skeletons of birds and humans.

Comparative anatomy has providedevidence of common descent,and has assisted in the classification of animals.[2]

History

editThe first specifically anatomical investigation separate from a surgical or medical procedure is associated by

.[3]Leonardo da Vincimade notes for a planned anatomical treatise in which he intended to compare the hands of various animals including bears.[4]Pierre Belon,a French naturalist born in 1517, conducted research and held discussions ondolphinembryos as well as the comparisons between the skeletons of birds to the skeletons of humans. His research led to modern comparative anatomy.[5]

Around the same time,Andreas Vesaliuswas also making some strides of his own. A young anatomist of Flemish descent made famous by a penchant for amazing charts, he was systematically investigating and correcting the anatomical knowledge of the Greek physician Galen. He noticed that many of Galen's observations were not even based on actual humans. Instead, they were based on other animals such as non-humanapes,monkeys,andoxen.[6]In fact, he entreated his students to do the following, in substitution for human skeletons, as cited by Edward Tyson: "If you can't happen to see any of these, dissect an Ape, carefully view each Bone, &c...." Then he advises what sort of Apes to make choice of, as most resembling a Man: And conclude "One ought to know the Structure of all the Bones either in a Humane Body, or in an Apes; 'tis best in both; and then to go to the Anatomy of the Muscles."[7]Up until that point, Galen and his teachings had been the authority on human anatomy. The irony is that Galen himself had emphasized the fact that one should make one's own observations instead of using those of another, but this advice was lost during the numerous translations of his work. AsVesaliusbegan to uncover these mistakes, other physicians of the time began to trust their own observations more than those of Galen. An interesting observation made by some of these physicians was the presence of homologous structures in a wide variety of animals which included humans. These observations were later used byDarwinas he formed his theory ofNatural Selection.[8]

Edward Tysonis regarded as the founder of modern comparative anatomy. He is credited with determining thatwhalesanddolphinsare, in fact, mammals. Also, he concluded thatchimpanzeesare more similar to humans than tomonkeysbecause of their arms.Marco Aurelio Severinoalso compared various animals, including birds, in hisZootomia democritaea,one of the first works of comparative anatomy. In the 18th and 19th century, great anatomists likeGeorge Cuvier,Richard OwenandThomas Henry Huxleyrevolutionized our understanding of the basic build andsystematicsofvertebrates,laying the foundation forCharles Darwin's work onevolution.An example of a 20th-century comparative anatomist isVictor Negus,who worked on the structure and evolution of the larynx. Until the advent of genetic techniques likeDNA sequencing,comparative anatomy together withembryologywere the primary tools for understandingphylogeny,as exemplified by the work ofAlfred Romer.[citation needed]

Concepts

editTwo major concepts of comparative anatomy are:

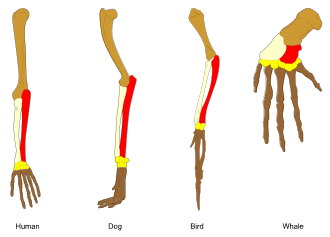

- Homologous structures- structures (body parts/anatomy) which are similar in different species because the species havecommon descentand have evolved, usually divergently, from a shared ancestor. They may or may not perform the same function. An example is the forelimb structure shared bycatsandwhales.

- Analogous structures- structures similar in different organisms because, inconvergent evolution,they evolved in asimilar environment,rather than were inherited from a recent common ancestor. They usually serve the same or similar purposes. An example is the streamlined torpedo body shape ofporpoisesandsharks.So even though they evolved from different ancestors, porpoises and sharks developed analogous structures as a result of their evolution in the same aquatic environment. This is known as ahomoplasy.[9]

Uses

editComparative anatomy has long served asevidence for evolution,now joined in that role bycomparative genomics;[10]it indicates that organisms share a common ancestor.

It also assists scientists in classifying organisms based on similar characteristics of their anatomical structures. A common example of comparative anatomy is the similar bone structures in forelimbs of cats, whales, bats, and humans. All of these appendages consist of the same basic parts; yet, they serve completely different functions. The skeletal parts which form a structure used for swimming, such as a fin, would not be ideal to form a wing, which is better-suited for flight. One explanation for the forelimbs' similar composition is descent with modification. Through random mutations and natural selection, each organism's anatomical structures gradually adapted to suit their respective habitats.[11]The rules for development ofspecialcharacteristics which differ significantly from generalhomologywere listed byKarl Ernst von Baerasthe laws now named after him.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^Gaucher EA, Kratzer JT, Randall RN (January 2010)."Deep phylogeny--how a tree can help characterize early life on Earth".Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology.2(1): a002238.doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a002238.PMC2827910.PMID20182607.

- ^National Academy of Sciences (US) (22 April 1999).Science and Creationism.doi:10.17226/6024.ISBN978-0-309-06406-4.PMID25101403.

- ^Blits KC (April 1999). "Aristotle: form, function, and comparative anatomy".The Anatomical Record.257(2): 58–63.doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990415)257:2<58::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-I.PMID10321433.S2CID38940794.

- ^Bean, Jacob; Stampfle, Felice (1965).Drawings from New York Collections I: The Italian Renaissance.Greenwich, CT: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 28.

- ^Gudger EW (1934). "The Five Great Naturalists of the Sixteenth Century: Belon, Rondelet, Salviani, Gesner and Aldrovandi: A Chapter in the History of Ichthyology".Isis.22(1): 21–40.doi:10.1086/346870.S2CID143961902.

- ^Mesquita ET, Souza Júnior CV, Ferreira TR (March 2015)."Andreas Vesalius 500 years--A Renaissance that revolutionized cardiovascular knowledge".Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Cardiovascular.30(2): 260–5.doi:10.5935/1678-9741.20150024.PMC4462973.PMID26107459.

- ^Edward Tyson, Orang-Outang..., 1699, p. 59.

- ^Caldwell R (2006)."Comparative Anatomy: Andreas Vesalius".University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived fromthe originalon 23 November 2010.Retrieved17 February2011.

- ^Kardong KV (2015).Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution.New York: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 15–16.ISBN978-0-07-802302-6.

- ^Hardison RC (November 2003)."Comparative genomics".PLOS Biology.1(2): E58.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0000058.PMC261895.PMID14624258.

- ^Campbell NA, Reece JB (February 2002).Biology(6th ed.). San Francisco, CA:Benjamin Cummings.pp.438–439.ISBN978-0-8053-6624-2.OCLC1053072597.

Further reading

edit- Lőw P, Molnár K, Kriska G (2016).Atlas of Animal Anatomy and Histology.Springer.ISBN978-3-319-25172-1.

- Wake MH, ed. (1979).Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy(3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-87013-7.

- Zboray G, Kovács Z, Kriska G, Molnár K, Pálfia Z (2010).Atlas of comparative sectional anatomy of 6 invertebrates and 5 vertebrates.Wien: Springer. p. 295.ISBN978-3-211-99763-5.