Elvin Ray Jones(September 9, 1927 – May 18, 2004) was an American jazz drummer of thepost-bopera.[1]Most famously a member ofJohn Coltrane's quartet, with whom he recorded from late 1960 to late 1965, Jones appeared on such albums asMy Favorite Things,A Love Supreme,AscensionandLive at Birdland.After 1966, Jones led his own trio, and later larger groups under the nameThe Elvin Jones Jazz Machine.His brothersHankandThadwere also celebrated jazz musicians with whom he occasionally recorded.[1]Elvin was inducted into theModern DrummerHall of Fame in 1995.[2]In hisThe History of Jazz,jazz historian and criticTed Gioiacalls Jones "one of the most influential drummers in the history of jazz".[3]He was also ranked at Number 23 onRolling Stonemagazine's "100 Greatest Drummers of All Time".

Elvin Jones | |

|---|---|

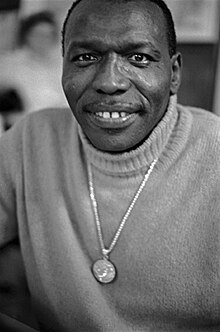

Jones in 1979 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Elvin Ray Jones |

| Born | September 9, 1927 Pontiac, Michigan,U.S. |

| Died | May 18, 2004(aged 76) Englewood, New Jersey,U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1948–2004 |

Early life and education

editElvin Jones was born inPontiac, Michigan,[4]to parents Henry and Olivia Jones, who had moved to Michigan fromVicksburg, Mississippi.[5]His elder brothers were pianistHank Jonesand trumpeterThad Jones,both highly regarded musicians.[6]By age two, he said, drums held a special fascination for him. He would watch thecircusparades go past his home as a child, and was particularly excited by themarching banddrummers. Following this early passion, Elvin joined his high school's black marching band, where he developed his foundation inrudiments.

Career

edit1946–1949: Military service

editJones served in theUnited States Armyfrom 1946 to 1949.[6]With his mustering-out pay (and an additional $35 borrowed from his sister), Jones purchased his firstdrumset.[7]

1949–1960: Professional musician beginnings

editJones began his professional career in 1949 with a short-lived gig in a club onDetroit's Grand River Street.[5]Eventually he went on to play with artists includingBilly MitchellandWardell Gray.In 1955, after a failed audition for theBenny Goodmanband, he found work inNew York City,joiningMiles DavisandCharles Mingus[5]for theirBlue Moodsalbum on Mingus's co-ownedDebutlabel.[8]During the late 1950s, Jones was a member of theSonny Rollinstrio[6]that recorded most of the albumA Night at the Village Vanguard,an album cited as a high point for both Rollins and for 1950s jazz in general.[9][10]

1960–1966: Association with John Coltrane

editIn 1960, he began playing withJohn Coltrane.[4]By 1962, he had become an integral member of the classic John Coltrane Quartet along with bassistJimmy Garrisonand pianistMcCoy Tyner.[4]Jones and Coltrane would often play extendedduetpassages. This band is widely considered to have redefined "swing"(therhythmicfeel of jazz), in much the same way thatLouis Armstrong,Charlie Parker,and others had done during earlier stages of jazz's development. Jones said of that period playing with Coltrane: "Every night when we hit the bandstand—no matter if we'd come five hundred or a thousand miles—the weariness just dropped from us. It was one of the most beautiful things a man can experience. If there is anything like perfect harmony in human relationships, that band was as close as you can come."[5]

Jones stayed with Coltrane until early 1966. By then, Jones was not entirely comfortable with Coltrane's new direction, especially as hispolyrhythmicstyle clashed with the "multidirectional" approach of the group's second drummer,Rashied Ali."I couldn't hear what was going on... I felt I just couldn't contribute."[5]

Post-Coltrane career

editJones remained active after leaving the Coltrane group, and led several bands in the late 1960s and 1970s that are considered influential groups.[6]Notable among them was a trio formed with saxophonist and multi-instrumentalistJoe Farrelland (ex-Coltrane) bassistJimmy Garrison,with whom he recorded theBlue NotealbumsPuttin' It TogetherandThe Ultimate.Jones recorded extensively for Blue Note under his own name in the late 1960s and early 1970s with groups that featured prominent as well as up and coming musicians. The two-volumeLive at the Lighthouseshowcases a 21- and 26-year-oldSteve GrossmanandDave Liebman,respectively. Jones also played on many albums of the "modal jazz era", such asThe Real McCoywith McCoy Tyner andSpeak No EvilwithWayne Shorter.

Beginning in the early 1980s, Jones performed and recorded with his own group, theElvin Jones Jazz Machine,whose lineup changed through the years.[11]BothSonny FortuneandRavi Coltrane,John Coltrane's son, played saxophone with the Jazz Machine in the early 1990s, appearing together with Jones onIn EuropeonEnja Recordsin 1991. His final recording as a band leader,The Truth: Heard Live at the Blue Note,recorded in 1999 and issued in 2004, featured an enlarged version of his Jazz Machine—Antoine Roney (sax),Robin Eubanks(trombonist),Darren Barrett(trumpet),Carlos McKinney(piano),Gene Perla(bass), and guest saxophonistMichael Brecker.[12]In 1990 and 1992, the Elvin Jones Jazz Machine partnered withWynton Marsalis,performing atThe Bottom Linein New York.[13]Among his last recordings was accompanying his brother, pianist Hank Jones, and bassist Richard Davis on an album titledAutumn Leavesunder the name The Great Jazz Trio.[11][14]

Other musicians who made significant contributions to Jones's music during this period were baritone saxophonistPepper Adams,tenor saxophonistsGeorge ColemanandFrank Foster,trumpeterLee Morgan,bassistGene Perla,keyboardistJan Hammerandjazz–world musicgroupOregon.

In 1969, Jones played drums for beat poetAllen Ginsberg's 1970 LPSongs of Innocence and Experience,a musical adaptation ofWilliam Blake'spoetry collection of the same name.[15]

He appeared as the villain Job Cain in the 1971 musicalWestern filmZachariah,[16]in which he performed a drum solo after winning a saloon gunfight.[16]

Jones, who taught regularly, often took part in clinics, played in schools, and gave free concerts inprisons.His lessons emphasized music history as well as drumming technique. In 2001, Jones was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Music fromBerklee College of Music.[17]

Death

editElvin Jones died of heart failure inEnglewood, New Jersey,on May 18, 2004.[18]He was survived by his first wife Shirley, children: Elvin Nathan Jones and Rose-Marie Jones, and his second common-law wife Keiko Okuya.[19]

Influence

editJones's sense of timing,polyrhythms,dynamics,timbre,andlegato phrasinghelped bring the drumset to the foreground. In a 1970 profile published inLife Magazine,Albert Goldmandubbed Jones "the world's greatest rhythm drummer",[20]and his free-flowing style was a major influence on many leading drummers, includingChristian Vander(Magma),Mitch Mitchell[21](whomJimi Hendrixcalled "my Elvin Jones"[22]),Ginger Baker,[23]Bill Bruford,[24]John Densmore(The Doors) andJanet Weiss(Sleater-Kinney).

Discography

editFilmography

edit- 1979A Different Drummer(Rhapsody)[1]

- 1996Elvin Jones: Jazz Machine(VIEW)[25]

- 1971Zachariah,directed byGeorge Englund

References

edit- ^abcYanow, Scott."Elvin Jones".AllMusic.RetrievedOctober 19,2011.

- ^"Modern Drummer's Readers Poll Archive, 1979–2014".Modern Drummer.RetrievedAugust 10,2015.

- ^Gioia, Ted (1997).The history of jazz.New York: Oxford University Press. p. 304.ISBN0-19-512653-X.

- ^abcColin Larkin,ed. (1997).The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music(Concise ed.).Virgin Books.pp. 682–3.ISBN1-85227-745-9.

- ^abcdeBalliett, Whitney (May 18, 1968)."A Walk to the Park, Profile (Elvin Jones)"(PDF).bangthedrumschool.com.The New Yorker. pp. 45–70.Archived(PDF)from the original on December 30, 2021.RetrievedDecember 30,2021.

- ^abcdColin Larkin,ed. (1992).The Guinness Who's Who of Jazz(First ed.).Guinness Publishing.p. 230/1.ISBN0-85112-580-8.

- ^Gross, Terry."Elvin Jones NPR interview".NPR.org.RetrievedMay 30,2007.

- ^Werlin, Mark (March 11, 2017)."Charles Mingus And Miles Davis: Changing Moods".www.allaboutjazz.com.All About Jazz.RetrievedDecember 30,2021.

- ^Yanow, Scott (November 2, 2010)."Hard Bop (Essay)".Allmusic.RetrievedAugust 24,2012.

- ^Cook, Richard and Brian Morton (2008),The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings(9th edn), Penguin, p. 1233.

- ^abMattingly, Rick."Elvin Jones".PAS.org.Percussive Arts Society.RetrievedDecember 30,2021.

- ^Kelman, John (October 13, 2004)."Elvin Jones Jazz Machine: The Truth: Heard Live At The Blue Note".www.AllAboutJazz.com.All About Jazz.RetrievedDecember 30,2021.

- ^"Elvin Jones Jazz Machine with Wynton Marsalis".wyntonmarsalis.org.RetrievedDecember 30,2021.

- ^"The Great Jazz Trio - Autumn Leaves".www.discogs.com.May 18, 2004.RetrievedDecember 30,2021.Recorded 2002; released 2004.

- ^Jurek, Thom (2017)."The Complete Songs of Innocence and Experience - Allen Ginsberg".AllMusic.RetrievedApril 28,2019.

- ^abGreenspun, Roger(January 25, 1971)."Zachariah (1970) Screen: 'Zachariah,' an odd Western".The New York Times.

- ^"Berklee Honors Rollins, Holds Summer Clinics".Jazztimes.com.RetrievedJuly 21,2017.

- ^"Elvin Jones, Jazz Drummer With Coltrane, Dies at 76".The New York Times.May 19, 2004.RetrievedDecember 4,2017.

- ^"Final Bar: Jazz Obituaries".downbeat.com.December 20, 2022.RetrievedJune 21,2024.

- ^Goldman, Albert (February 6, 1970)."Elvin Jones' Kinesthetic Trip: World's Best Rhythm Drummer".Life.Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^Herman, Gary (December 1981/January 1982)."The Continuing Experience of Mitch Mitchell".Modern Drummer.Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^Heatley, Michael;Shapiro, Harry (2009).Jimi Hendrix Gear: The Guitars, Amps & Effects That Revolutionized Rock 'n' Roll.Voyageur Press. p. 166.

- ^Gillin, Beth (January 13, 1968)."The Homogenized Sound".The Camden Courier-Post.Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^Stump, Paul (1997).The Music's All that Matters: A History of Progressive Rock.Quartet Books Limited. p. 49.ISBN0-7043-8036-6.

- ^Jones, Elvin."VIEW DVD Listing".View.com.RetrievedOctober 19,2011.