Gabapentinoids,also known asα2δ ligands,are aclass of drugsthat arederivativesof theinhibitory neurotransmittergamma-Aminobutyric acid(GABA) (i.e.,GABA analogues) whichblockα2δ subunit-containingvoltage-dependent calcium channels(VDCCs).[1][2][3][4]This site has been referred to as thegabapentin receptor(α2δ subunit), as it is thetargetof the drugsgabapentinandpregabalin.[5]

| Gabapentinoid | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Gabapentin,the prototypical gabapentinoid | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | α2δ ligands; Ca2+α2δ ligands |

| Use | Epilepsy;Neuropathic pain;Postherpetic neuralgia;Diabetic neuropathy;Fibromyalgia,Generalized anxiety disorder;Restless legs syndrome |

| ATC code | N03AX |

| Biological target | α2δ subunit-containingVDCCs |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Clinically used gabapentinoids include gabapentin, pregabalin, andmirogabalin,[3][4]as well as a gabapentinprodrug,gabapentin enacarbil.[6]Additionally,phenibuthas been found to act as a gabapentinoid in addition to its action of functioning as aGABABreceptoragonist.[7][8]Further analogues likeimagabalinare inclinical trialsbut have not yet been approved.[9]Other gabapentinoids which are used inscientific researchbut have not been approved for medical use includeatagabalin,4-methylpregabalinandPD-217,014.[citation needed]

Medical uses

editGabapentinoids are approved for the treatment ofepilepsy,postherpetic neuralgia,neuropathic painassociated withdiabetic neuropathy,fibromyalgia,generalized anxiety disorder,andrestless legs syndrome.[3][6][10]Someoff-label usesof gabapentinoids include the treatment ofinsomnia,migraine,social phobia,panic disorder,mania,bipolar disorder,andalcohol withdrawal.[6][11]Existing evidence on the use of gabapentinoids inchronic lower back painis limited, and demonstrates significant risk of adverse effects, without any demonstrated benefit.[12]The main side-effects include: a feeling of sleepiness and tiredness, decreased blood pressure, nausea, vomiting and also glaucomatous visual hallucinations.[13]

Side effects

editPharmacology

editPharmacodynamics

editGabapentinoids areligandsof the auxiliaryα2δ subunitsite of certainVDCCs,and thereby act asinhibitorsof α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs.[14][1]There are two drug-binding α2δ subunits,α2δ-1andα2δ-2,and the gabapentinoids show similaraffinityfor (and hence lack ofselectivitybetween) these two sites.[1]The gabapentinoids are selective in their binding to the α2δ VDCC subunit.[14][4]However, phenibut uniquely also binds to and acts as anagonistof theGABABreceptorwith lower affinity (~5- to 10-fold in one study).[15][7]Despite the fact that gabapentinoids areGABA analogues,gabapentin and pregabalin do not bind to theGABA receptors,do not convert intoGABAorGABA receptor agonistsin vivo,and do not modulate GABAtransportormetabolism.[14][16]There is currently no evidence that the relevant actions of gabapentin and pregabalin are mediated by any mechanism other than inhibition of α2δ-containing VDCCs.[17]Although, gabapentinoids such as gabapentin, but not pregabalin, have been found to activate Kvvoltage-gated potassium channels (KCNQ).[18]

Theendogenousα-amino acidsL-leucineandL-isoleucine,which closely resemble the gabapentinoids inchemical structure,are apparent ligands of the α2δ VDCC subunit with similar affinity as gabapentin and pregabalin (e.g.,IC50= 71 nM forL-isoleucine), and are present in humancerebrospinal fluidat micromolar concentrations (e.g., 12.9 μM forL-leucine, 4.8 μM forL-isoleucine).[2]It has been hypothesized that they may be the endogenous ligands of the subunit and that they maycompetitively antagonizethe effects of gabapentinoids.[2][19]In accordance, while gabapentin and pregabalin havenanomolaraffinities for the α2δ subunit, their potenciesin vivoare in the lowmicromolarrange, and competition for binding by endogenousL-amino acids has been said to likely be responsible for this discrepancy.[17]

In one study, the affinity (Ki) values of gabapentinoids for the α2δ subunit expressed in rat brain were found to be 0.05 μM for gabapentin, 23 μM for (R)-phenibut, 39 μM for (S)-phenibut, and 156 μM forbaclofen.[7]Their affinities (Ki) for the GABABreceptor were >1 mM for gabapentin, 92 μM for (R)-phenibut, >1 mM for (S)-phenibut, and 6 μM for baclofen.[7]Based on the low affinity of baclofen for the α2δ subunit relative to the GABAB(26-fold difference), its affinity for the α2δ subunit is unlikely to be of pharmacological importance.[7]

Pregabalin has demonstrated significantly greaterpotency(about 2.5-fold) than gabapentin in clinical studies.[20]

Pharmacokinetics

editAbsorption

editGabapentin and pregabalin areabsorbedfrom theintestinesby anactive transportprocess mediated via thelarge neutral amino acid transporter 1(LAT1, SLC7A5), a transporter foramino acidssuch asL-leucineandL-phenylalanine.[1][14][21]Very few (less than 10 drugs) are known to be transported by this transporter.[22]Unlike gabapentin, which is transported solely by the LAT1,[21][23]pregabalin seems to be transported not only by the LAT1 but also by other carriers.[1]The LAT1 is easilysaturable,so thepharmacokineticsof gabapentin are dose-dependent, with diminished bioavailability and delayed peak levels at higher doses.[1]Conversely, this is not the case for pregabalin, which shows linear pharmacokinetics and no saturation of absorption.[1]Similarly,gabapentin enacarbilis transported not by the LAT1 but by themonocarboxylate transporter 1(MCT1) and thesodium-dependent multivitamin transporter(SMVT), and no saturation of bioavailability has been observed with the drug up to a dose of 2,800 mg.[24]Similarly to gabapentin and pregabalin,baclofen,a close analogue of phenibut (baclofen specifically being 4-chlorophenibut), is transported by the LAT1, although it is a relatively weaksubstratefor the transporter.[22][25]

Theoralbioavailabilityof gabapentin is approximately 80% at 100 mg administered three times daily once every 8 hours, but decreases to 60% at 300 mg, 47% at 400 mg, 34% at 800 mg, 33% at 1,200 mg, and 27% at 1,600 mg, all with the same dosing schedule.[23][24]Conversely, the oral bioavailability of pregabalin is greater than or equal to 90% across and beyond its entire clinical dose range (75 to 900 mg/day).[23]Food does not significantly influence the oral bioavailability of pregabalin.[23]Conversely, food increases thearea-under-curve levelsof gabapentin by about 10%.[23]Drugs that increase the transit time of gabapentin in thesmall intestinecan increase its oral bioavailability; when gabapentin was co-administered with oralmorphine(which slowsintestinalperistalsis),[26]the oral bioavailability of a 600 mg dose of gabapentin increased by 50%.[23]The oral bioavailability of gabapentin enacarbil (as gabapentin) is greater than or equal to 68%, across all doses assessed (up to 2,800 mg), with a mean of approximately 75%.[24][1]In contrast to the other gabapentinoids, the pharmacokinetics of phenibut have been little-studied, and its oral bioavailability is unknown.[15]However, it would appear to be at least 63% at a single dose of 250 mg, based on the fact that this fraction of phenibut was recovered from theurineunchanged in healthy volunteers administered this dose.[15]

Gabapentin at a low dose of 100 mg has aTmax(time topeak levels) of approximately 1.7 hours, while the Tmaxincreases to 3 to 4 hours at higher doses.[1]The Tmaxof pregabalin is generally less than or equal to 1 hour at doses of 300 mg or less.[1]However, food has been found to substantially delay the absorption of pregabalin and to significantly reduce peak levels without affecting the bioavailability of the drug; Tmaxvalues for pregabalin of 0.6 hours in a fasted state and 3.2 hours in a fed state (5-fold difference), and theCmaxis reduced by 25–31% in a fed versus fasted state.[23]In contrast to pregabalin, food does not significantly affect the Tmaxof gabapentin and increases the Cmaxof gabapentin by approximately 10%.[23]The Tmaxof theinstant-release(IR) formulation of gabapentin enacarbil (as active gabapentin) is about 2.1 to 2.6 hours across all doses (350–2,800 mg) with single administration and 1.6 to 1.9 hours across all doses (350–2,100 mg) with repeated administration.[27]Conversely, the Tmaxof theextended-release(XR) formulation of gabapentin enacarbil is about 5.1 hours at a single dose of 1,200 mg in a fasted state and 8.4 hours at a single dose of 1,200 mg in a fed state.[27]The Tmaxof phenibut has not been reported,[15]but theonset of actionand peak effects have been described as occurring at 2 to 4 hours and 5 to 6 hours, respectively, after oral ingestion in recreational users taking high doses (1–3 g).[28]

Distribution

editGabapentin, pregabalin, and phenibut all cross theblood–brain barrierand enter thecentral nervous system.[14][15]However, due to their lowlipophilicity,[23]the gabapentinoids require active transport across the blood–brain barrier.[21][14][29][30]The LAT1 is highly expressed at the blood–brain barrier[31]and transports the gabapentinoids that bind to it across into thebrain.[21][14][29][30]As with intestinal absorption of gabapentin mediated by LAT1, transport of gabapentin across the blood–brain barrier by LAT1 is saturable.[21]Gabapentin does not bind to other drug transporters such asP-glycoprotein(ABCB1) orOCTN2(SLC22A5).[21]

Gabapentin and pregabalin are not significantlybound to plasma proteins(<1%).[23]The phenibut analogue baclofen shows low plasma protein binding of 30%.[32]

Metabolism

editGabapentin, pregabalin, and phenibut all undergo little or nometabolism.[1][23][15]Conversely, gabapentin enacarbil, which acts as aprodrugof gabapentin, must undergoenzymatichydrolysisto becomeactive.[1][24]This is done via non-specificesterasesin theintestinesand to a lesser extent in theliver.[1]

Elimination

editGabapentin, pregabalin, and phenibut are alleliminatedrenallyin theurine.[23][15]They all have relatively shortelimination half-lives,with reported values of 5.0 to 7.0 hours, 6.3 hours, and 5.3 hours, respectively.[23][15]Similarly, the terminal half-life of gabapentin enacarbil IR (as active gabapentin) is short at approximately 4.5 to 6.5 hours.[27]Because of its short elimination half-life, gabapentin must be administered 3 to 4 times per day to maintain therapeutic levels.[24]Similarly, pregabalin has been given 2 to 3 times per day in clinical studies.[23]Phenibut, also, is taken 3 times per day.[33][34]Conversely, gabapentin enacarbil is taken twice a day and gabapentin XR (brand name Gralise) is taken once a day.[35]

Chemistry

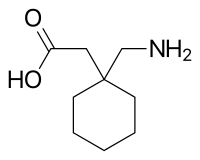

editThe gabapentinoids are 3-substitutedderivativesof GABA; hence, they areGABA analogues,as well asγ-amino acids.[3][4]Specifically, pregabalin is (S)-(+)-3-isobutyl-GABA, phenibut is 3-phenyl-GABA,[15]and gabapentin is a derivative of GABA with acyclohexaneringat the 3 position (or, somewhat inappropriately named, 3-cyclohexyl-GABA).[36][37][38]The gabapentinoids alsoclosely resembletheα-amino acidsL-leucineandL-isoleucine,and this may be of greater relevance in relation to theirpharmacodynamicsthan their structural similarity to GABA.[2][19][36]

History

editGabapentin, under the brand name Neurontin, was first approved in May 1993 for the treatment ofepilepsyin theUnited Kingdom,and was marketed in theUnited Statesin 1994.[39][40]Subsequently, gabapentin was approved in the United States for the treatment ofpostherpetic neuralgiain May 2002.[41]Ageneric versionof gabapentin first became available in the United States in 2004.[42]An extended-release formulation of gabapentin for once-daily administration, under the brand name Gralise, was approved in the United States for the treatment postherpetic neuralgia in January 2011.[43][44]

Pregabalin, under the brand name Lyrica, was approved inEuropein 2004 and was introduced in the United States in September 2005 for the treatment of epilepsy, postherpetic neuralgia, andneuropathic painassociated withdiabetic neuropathy.[38][45][46][47]It was subsequently approved for the treatment offibromyalgiain the United States in June 2007.[38][45][47]Pregabalin was also approved for the treatment ofgeneralized anxiety disorderin Europe in 2005, though it has not been approved for this indication in the United States.[45][38][48][49]

Gabapentin enacarbil, under the brand name Horizant, was introduced in the United States for the treatment ofrestless legs syndromein April 2011 and was approved for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in June 2012.[50]

Phenibut, marketed under the brand names Anvifen, Fenibut, and Noofen, was introduced inRussiain the 1960s for the treatment ofanxiety,insomnia,and a variety of other conditions.[15][51]It was not discovered to act as a very weak (3.5 orders of magnitude less potent) gabapentinoid until 2015.[7]

Baclofenmarketed under the brandname of Lioresal was introduced in the United States in 1977 for the treatment ofspasticityis chemically similar to phenibut but is usually not considered a gabapentinoid. Mirogabalin, under the brand name Tarlige, was approved for the treatment of neuropathic pain and postherpetic neuralgia in Japan in January 2019.[52]

A longitudinal trend study analyzed multinational sales data, revealing an overall increase in gabapentinoid consumption across 65 countries and regions from 2008 to 2018. This comprehensive analysis underscores the widespread use of gabapentinoids beyond their initial antiseizure applications, reflecting their role in treating a broad spectrum of conditions.[53]

Society and culture

editRecreational use

editGabapentinoids produceeuphoriaat high doses, with effects similar toGABAergiccentral nervous systemdepressantssuch asalcohol,γ-hydroxybutyric acid(GHB), andbenzodiazepines,and are used asrecreational drugs(at 3–20 times typical clinical doses).[54][20][28]The overallabuse potentialis considered to be low and notably lower than that of other drugs such as alcohol, benzodiazepines,opioids,psychostimulants,and otherillicit drugs.[54][20]In any case, due to its recreational potential, pregabalin is aschedule Vcontrolled substancein theUnited States.[54]In April 2019,[55]the United Kingdom scheduled gabapentin and pregabalin as Class C drugs under theMisuse of Drugs Act 1971,and as Schedule 3 under theMisuse of Drugs Regulations 2001.[56]However, it is not a controlled substance inCanada,orAustralia,and the other gabapentinoids, including phenibut, are not controlled substances either.[54]As such, they are mostly legal intoxicants.[54][20][28]

Toleranceto gabapentinoids is reported to develop very rapidly with repeated use, although to also dissipate quickly upon discontinuation, andwithdrawalsymptomssuch asinsomnia,nausea,headache,anddiarrheahave been reported.[54][20]More severe withdrawal symptoms, such as severe reboundanxiety,have been reported with phenibut.[28]Because of the rapid tolerance with gabapentinoids, users often escalate their doses,[20]while other users may space out their doses and use sparingly to avoid tolerance.[28]

List of agents

editApproved

edit- Gabapentin(Neurontin, Gabagamma)

- Gabapentin extended-release(Gralise)

- Gabapentin enacarbil(Horizant)

- Mirogabalin(Tarlige)

- Phenibut(Anvifen, Fenibut, Noofen)

- Pregabalin(Lyrica)

- Baclofen

Not approved

editReferences

edit- ^abcdefghijklmCalandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M (2016). "Alpha2delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use".Expert Rev Neurother.16(11): 1263–1277.doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1202764.PMID27345098.S2CID33200190.

- ^abcdDooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, Feltner D (2007). "Ca2+ channel alpha2delta ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission".Trends Pharmacol. Sci.28(2): 75–82.doi:10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.006.PMID17222465.

- ^abcdElaine Wyllie,Gregory D. Cascino, Barry E. Gidal, Howard P. Goodkin (February 17, 2012).Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 423.ISBN978-1-4511-5348-4.

- ^abcdHonorio Benzon, James P. Rathmell, Christopher L. Wu, Dennis C. Turk, Charles E. Argoff, Robert W Hurley (September 11, 2013).Practical Management of Pain.Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1006.ISBN978-0-323-17080-2.

- ^Eroglu Ç,Allen NJ, Susman MW, O'Rourke NA, Park CY, Özkan E, Chakraborty C, Mulinyawe SB, Annis DS, Huberman AD, Green EM, Lawler J, Dolmetsch R, Garcia KC, Smith SJ, Luo ZD, Rosenthal A, Mosher DF, Barres BA (2009)."Gabapentin Receptor α2δ-1 is a Neuronal Thrombospondin Receptor Responsible for Excitatory CNS Synaptogenesis".Cell.139(2): 380–92.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.025.PMC2791798.PMID19818485.

- ^abcDouglas Kirsch (October 10, 2013).Sleep Medicine in Neurology.John Wiley & Sons. p. 241.ISBN978-1-118-76417-6.

- ^abcdefZvejniece L, Vavers E, Svalbe B, Veinberg G, Rizhanova K, Liepins V, Kalvinsh I, Dambrova M (2015). "R-phenibut binds to the α2-δ subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels and exerts gabapentin-like anti-nociceptive effects".Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.137:23–9.doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2015.07.014.PMID26234470.S2CID42606053.

- ^Vavers E, Zvejniece L, Svalbe B, Volska K, Makarova E, Liepinsh E, Rizhanova K, Liepins V, Dambrova M (2015). "The neuroprotective effects of R-phenibut after focal cerebral ischemia".Pharmacological Research.113(Pt B): 796–801.doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2015.11.013.ISSN1043-6618.PMID26621244.

- ^Vinik A, Rosenstock J, Sharma U, Feins K, Hsu C, Merante D (2014)."Efficacy and Safety of Mirogabalin (DS-5565) for the Treatment of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo- and Active Comparator–Controlled, Adaptive Proof-of-Concept Phase 2 Study".Diabetes Care.37(12): 3253–61.doi:10.2337/dc14-1044.PMID25231896.

- ^Frye M, Moore K (2009)."Gabapentin and Pregabalin".In Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (eds.).The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology.pp. 767–77.doi:10.1176/appi.books.9781585623860.as38.ISBN978-1-58562-309-9.

- ^"Pharmacotherapy Update | Pregabalin (Lyrica®):Part I".

- ^Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, AlAmri R, Kamath S, Thabane L, Devereaux PJ, Bhandari M, Tsai AC (August 15, 2017)."Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials".PLOS Medicine.14(8): e1002369.doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002369.PMC5557428.PMID28809936.

- ^"Side effects of gabapentin".nhs.uk.September 16, 2021.RetrievedNovember 21,2022.

- ^abcdefgSills GJ (2006). "The mechanisms of action of gabapentin and pregabalin".Curr Opin Pharmacol.6(1): 108–13.doi:10.1016/j.coph.2005.11.003.PMID16376147.

- ^abcdefghijLapin I (2001)."Phenibut (beta-phenyl-GABA): A tranquilizer and nootropic drug".CNS Drug Reviews.7(4): 471–481.doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00211.x.PMC6494145.PMID11830761.

- ^Uchitel OD, Di Guilmi MN, Urbano FJ, Gonzalez-Inchauspe C (2010)."Acute modulation of calcium currents and synaptic transmission by gabapentinoids".Channels (Austin).4(6): 490–6.doi:10.4161/chan.4.6.12864.hdl:11336/20897.PMID21150315.

- ^abStahl SM, Porreca F, Taylor CP, Cheung R, Thorpe AJ, Clair A (2013). "The diverse therapeutic actions of pregabalin: is a single mechanism responsible for several pharmacological activities?".Trends Pharmacol. Sci.34(6): 332–9.doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.001.PMID23642658.

- ^"Gabapentin is a potent activator of KCNQ3 and KCNQ5 potassium channels"(PDF).

- ^abDavies A, Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Wratten J, Douglas L, Dolphin AC (2007). "Functional biology of the alpha(2)delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels".Trends Pharmacol. Sci.28(5): 220–8.doi:10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.005.PMID17403543.

- ^abcdefSchifano F, D'Offizi S, Piccione M, Corazza O, Deluca P, Davey Z, Di Melchiorre G, Di Furia L, Farré M, Flesland L, Mannonen M, Majava A, Pagani S, Peltoniemi T, Siemann H, Skutle A, Torrens M, Pezzolesi C, van der Kreeft P, Scherbaum N (2011). "Is there a recreational misuse potential for pregabalin? Analysis of anecdotal online reports in comparison with related gabapentin and clonazepam data".Psychother Psychosom.80(2): 118–22.doi:10.1159/000321079.hdl:2299/9328.PMID21212719.S2CID11172830.

- ^abcdefDickens D, Webb SD, Antonyuk S, Giannoudis A, Owen A, Rädisch S, Hasnain SS, Pirmohamed M (2013). "Transport of gabapentin by LAT1 (SLC7A5)".Biochem. Pharmacol.85(11): 1672–83.doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.03.022.PMID23567998.

- ^abdel Amo EM, Urtti A, Yliperttula M (2008). "Pharmacokinetic role of L-type amino acid transporters LAT1 and LAT2".Eur J Pharm Sci.35(3): 161–74.doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2008.06.015.PMID18656534.

- ^abcdefghijklmnBockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, Chapel S, Janiczek N, Burger P (2010). "A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin".Clin Pharmacokinet.49(10): 661–9.doi:10.2165/11536200-000000000-00000.PMID20818832.S2CID16398062.

- ^abcdeAgarwal P, Griffith A, Costantino HR, Vaish N (2010)."Gabapentin enacarbil - clinical efficacy in restless legs syndrome".Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat.6:151–8.doi:10.2147/NDT.S5712.PMC2874339.PMID20505847.

- ^Kido Y, Tamai I, Uchino H, Suzuki F, Sai Y, Tsuji A (2001)."Molecular and functional identification of large neutral amino acid transporters LAT1 and LAT2 and their pharmacological relevance at the blood-brain barrier".J. Pharm. Pharmacol.53(4): 497–503.doi:10.1211/0022357011775794.PMID11341366.S2CID38717319.

- ^Khansari M, Sohrabi M, Zamani F (January 2013)."The Useage of Opioids and their Adverse Effects in Gastrointestinal Practice: A Review".Middle East J Dig Dis.5(1): 5–16.PMC3990131.PMID24829664.

- ^abcCundy KC, Sastry S, Luo W, Zou J, Moors TL, Canafax DM (2008). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of XP13512, a novel transported prodrug of gabapentin".J Clin Pharmacol.48(12): 1378–88.doi:10.1177/0091270008322909.PMID18827074.S2CID23598218.

- ^abcdeOwen DR, Wood DM, Archer JR, Dargan PI (2016). "Phenibut (4-amino-3-phenyl-butyric acid): Availability, prevalence of use, desired effects and acute toxicity".Drug Alcohol Rev.35(5): 591–6.doi:10.1111/dar.12356.hdl:10044/1/30073.PMID26693960.

- ^abGeldenhuys WJ, Mohammad AS, Adkins CE, Lockman PR (2015)."Molecular determinants of blood-brain barrier permeation".Ther Deliv.6(8): 961–71.doi:10.4155/tde.15.32.PMC4675962.PMID26305616.

- ^abMüller CE (2009). "Prodrug approaches for enhancing the bioavailability of drugs with low solubility".Chemistry & Biodiversity.6(11): 2071–83.doi:10.1002/cbdv.200900114.PMID19937841.S2CID32513471.

- ^Boado RJ, Li JY, Nagaya M, Zhang C, Pardridge WM (1999)."Selective expression of the large neutral amino acid transporter at the blood-brain barrier".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.96(21): 12079–84.Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612079B.doi:10.1073/pnas.96.21.12079.PMC18415.PMID10518579.

- ^Mervyn Eadie, J.H. Tyrer (December 6, 2012).Neurological Clinical Pharmacology.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 73–.ISBN978-94-011-6281-4.

- ^Ozon Pharm,Fenibut(PDF),archived fromthe original(PDF)on September 16, 2017,retrievedSeptember 15,2017

- ^Регистр лекарственных средств России ([Russian Medicines Register])."Фенибут (Phenybutum)"[Fenibut (Phenybutum)].RetrievedSeptember 15,2017.

- ^Alan D. Kaye (June 5, 2017).Pharmacology, An Issue of Anesthesiology Clinics E-Book.Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 98–.ISBN978-0-323-52998-3.

- ^abYogeeswari P, Ragavendran JV, Sriram D (2006). "An update on GABA analogs for CNS drug discovery".Recent Patents on CNS Drug Discovery.1(1): 113–8.doi:10.2174/157488906775245291.PMID18221197.

- ^Rose MA, Kam PC (2002)."Gabapentin: pharmacology and its use in pain management".Anaesthesia.57(5): 451–62.doi:10.1046/j.0003-2409.2001.02399.x.PMID11966555.S2CID27431734.

- ^abcdJames W. Wheless, James Willmore, Roger A. Brumback (2009).Advanced Therapy in Epilepsy.PMPH-USA. pp. 302–.ISBN978-1-60795-004-2.

- ^"Gabapentin - Pfizer - AdisInsight".

- ^Jie Jack Li (2014).Blockbuster Drugs: The Rise and Fall of the Pharmaceutical Industry.OUP USA. pp. 158–.ISBN978-0-19-973768-0.

- ^Irving G (2012)."Once-daily gastroretentive gabapentin for the management of postherpetic neuralgia: an update for clinicians".Ther Adv Chronic Dis.3(5): 211–8.doi:10.1177/2040622312452905.PMC3539268.PMID23342236.

- ^Diana Reed (March 2, 2012).The Other End of the Stethoscope: The Physician's Perspective on the Health Care Crisis.AuthorHouse. pp. 63–.ISBN978-1-4685-4410-7.

- ^"GoodRx - Error".

- ^"Gabapentin controlled release - Assertio Therapeutics - AdisInsight".

- ^abc"Pregabalin - Pfizer - AdisInsight".

- ^Raymond S. Sinatra, Jonathan S. Jahr, J. Michael Watkins-Pitchford (October 14, 2010).The Essence of Analgesia and Analgesics.Cambridge University Press. pp. 298–.ISBN978-1-139-49198-3.

- ^abVictor B. Stolberg (March 14, 2016).Painkillers: History, Science, and Issues.ABC-CLIO. pp. 76–.ISBN978-1-4408-3532-2.

- ^Michael S. Ritsner (June 16, 2010).Brain Protection in Schizophrenia, Mood and Cognitive Disorders.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 490–.ISBN978-90-481-8553-5.

- ^Thomas E Schlaepfer, Charles B. Nemeroff (September 1, 2012).Neurobiology of Psychiatric Disorders.Elsevier. pp. 353–.ISBN978-0-444-53500-9.

- ^Jeffrey S."FDA Approves Gabapentin Enacarbil for Postherpetic Neuralgia".Medscape.

- ^Drobizhev M, Fedotova A, Kikta S, Antohin E (2016)."Феномен аминофенилмасляной кислоты"[[Phenomenon of aminophenylbutyric acid]].Russian Medical Journal(in Russian).2017(24): 1657–1663.ISSN1382-4368.

- ^"Mirogabalin - Daiichi Sankyo Company - AdisInsight".

- ^Chan A, Yuen A, Tsai D (2023)."Gabapentinoid consumption in 65 countries and regions from 2008 to 2018: a longitudinal trend study".Nature Communications.14(1): 5005.doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40637-8.PMC10435503.PMID37591833.

- ^abcdefSchifano F (2014)."Misuse and abuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: cause for concern?".CNS Drugs.28(6): 491–6.doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0164-4.PMID24760436.

- ^"Pregabalin and gabapentin to be controlled as class C drugs".GOV.UK.RetrievedSeptember 29,2020.

- ^"Controlled drugs and drug dependence".British National Formulary.