"Jack the Giant Killer"is a Cornishfairy taleandlegendabout a young adult who slays a number of badgiantsduringKing Arthur's reign. The tale is characterised by violence, gore and blood-letting. Giants are prominent inCornish folklore,Breton mythologyandWelsh Bardic lore.Some parallels to elements and incidents inNorse mythologyhave been detected in the tale, and the trappings of Jack's last adventure with theGiantGaligantus suggest parallels withFrenchandBretonfairy tales such asBluebeard.Jack's belt is similar to the belt in "The Valiant Little Tailor",and his magical sword, shoes, cap, and cloak are similar to those owned byTom Thumbor those found inWelshandNorsemythology.

| Jack the Giant Killer | |

|---|---|

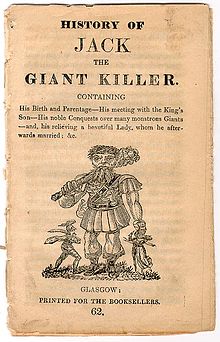

Chapbooktitle page | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Jack the Giant Killer |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Published in | English Fairy Tales |

| Related |

|

Jackand his tale are rarely referenced inEnglish literatureprior to the eighteenth century (there is an allusion to Jack the Giant Killer inWilliam Shakespeare'sKing Lear,where in Act 3, one character, Edgar, in his feigned madness, cries, "Fie, foh, and fum,/ I smell the blood of a British man" ). Jack's story did not appear in print until 1711. One scholar speculates the public had grown weary ofKing Arthurand Jack was created to fill the role.Henry Fielding,John Newbery,Samuel Johnson,Boswell,andWilliam Cowperwere familiar with the tale.

In 1962, afeature-length filmbased on the tale was released starringKerwin Mathews.The film made extensive use ofstop motionin the manner ofRay Harryhausen.

Plot

editThis plot summary is based on a text published c. 1760 by John Cotton and Joshua Eddowes, which in its turn was based on achapbookc. 1711, and reprinted inThe Classic Fairy Talesby Iona and Peter Opie in 1974.

The tale is set during the reign ofKing Arthurand tells of a youngCornishfarmer's son namedJackwho is not only strong but so clever he easily confounds the learned with his penetrating wit. Jack encounters a livestock-eatinggiantcalledCormoran(Cornish:'The Giant of the Sea' SWF:Kowr-Mor-An) and lures him to his death in apit trap.Jack is dubbed 'Jack the Giant-Killer' for this feat and receives not only the giant's wealth, but a sword and belt to commemorate the event.

A man-eating giant namedBlunderborevows vengeance for Cormoran's death and carries Jack off to an enchanted castle. Jack manages to slay Blunderbore and his brother Rebecks by hanging and stabbing them. He frees three ladies held captive in the giant's castle.

On a trip into Wales, Jack tricks a two-headed Welsh giant into slashing his own belly open. King Arthur's son now enters the story and Jack becomes his servant.

They spend the night with a three-headed giant and rob him in the morning. In gratitude for having spared his castle, the three-headed giant gives Jack a magic sword, a cap of knowledge, a cloak of invisibility, and shoes of swiftness.

On the road, Jack and the Prince meet an enchanted Lady servingLucifer.Jack breaks the spell with his magic accessories, beheads Lucifer, and the Lady marries the Prince. Jack is rewarded with membership in theRound Table.

Jack ventures forth alone with his magic shoes, sword, cloak, and cap to rid the realm of troublesome giants. He encounters a giant terrorizing a knight and his lady. He cuts off the giant's legs, then puts him to death. He discovers the giant's companion in a cave. Invisible in his cloak, Jack cuts off the giant's nose then slays him by plunging his sword into the monster's back. He frees the giant's captives and returns to the house of the knight and lady he earlier had rescued.

A banquet is prepared, but it is interrupted by the two-headed giantThunderdelchanting "Fee, fau, fum". Jack defeats and beheads the giant with a trick involving the house's moat and drawbridge.

Growing weary of the festivities, Jack sallies forth for more adventures and meets an elderly man who directs him to an enchanted castle belonging to the giantGalligantus(Galligantua, in theJoseph Jacobsversion). The giant holds captive many knights and ladies and a Duke's daughter who has been transformed into a white doe through the power of a sorcerer. Jack beheads the giant, the sorcerer flees, the Duke's daughter is restored to her true shape, and the captives are freed.

At the court of King Arthur, Jack marries the Duke's daughter and the two are given an estate where they live happily ever after.

Background

editTales of monsters and heroes are abundant around the world, making the source of "Jack the Giant Killer" difficult to pin down. However, the ascription of Jack's relation toCornwallsuggests aBrythonic(Celtic) origin. The earlyWelshtaleHow Culhwch won Olwen(tentatively dated to c. 1100), set inArthurianBritain places Arthur as chief among the kings of Britain.[1]The young heroCulhwch ap Cilyddmakes his way to his cousin Arthur's court atCelliwigin Cornwall where he demands Olwen as his bride; the beautiful daughter of the giantYsbaddaden Ben Cawr('Chief of Giants'). The Giant sets a series of impossible tasks which Arthur's championsBedwyrandCaiare honour-bound to fulfill before Olwen is released to the lad; and the Giant King must die. FolkloristsIona and Peter Opiehave observed inThe Classic Fairy Tales(1974) that "the tenor of Jack's tale, and some of the details of more than one of his tricks with which he outwits the giants, have similarities withNorse mythology."An incident betweenThorand the giantSkrymirin theProse Eddaof c. 1220, they note, resembles the incident between Jack and the stomach-slashing Welsh giant. The Opies further note that the Swedish tale of "The Herd-boy and the Giant" shows similarities to the same incident, and "shares an ancestor" with theGrimms's"The Valiant Little Tailor",a tale with wide distribution. According to the Opies, Jack's magical accessories – the cap of knowledge, the cloak of invisibility, the magic sword, and the shoes of swiftness – could have been borrowed from the tale ofTom Thumbor from Norse mythology, however older analogues in BritishCelticlore such asY Mabinogiand the tales ofGwyn ap Nudd,cognate with the IrishFionn mac Cumhaill,suggest that these represent attributes of the earlier Celtic gods such as the shoes associated with triple-headedLugus;WelshLleu Llaw Gyffesof theFourth Branch,Arthur's invincible swordCaledfwlchand hisMantle of InvisibilityGwennone of theThirteen Treasures of the Island of Britainmentioned in two of the branches; or the similar cloak ofCaswallawnin theSecond Branch.[2][3]Another parallel is the Greek demigodPerseus,who was given a magic sword, the winged sandals ofHermesand the 'cap of darkness' (borrowed fromHades) to slay thegorgonMedusa.Ruth B. Bottigheimer observes inThe Oxford Companion to Fairy Talesthat Jack's final adventure with Galigantus was influenced by the "magical devices" of French fairy tales.[4]The Opies conclude that analogues from around the world "offer no surety of Jack's antiquity."[3]

The Opies note that tales of giants were long known in Britain.King Arthur's encounter with the giant ofSt Michael's Mount– orMont Saint-Michelin Brittany[5]– was related byGeoffrey of MonmouthinHistoria Regum Britanniaein 1136, and published bySir Thomas Maloryin 1485 in the fifth chapter of the fifth book ofLe Morte d'Arthur:[3]

Then came to [King Arthur] an husbandman... and told him how there was... a great giant which had slain, murdered and devoured much people of the country... [Arthur journeyed to the Mount, discovered the giant roasting dead children,]... and hailed him, saying... [A]rise and dress thee, thou glutton, for this day shalt thou die of my hand. Then the glutton anon started up, and took a great club in his hand, and smote at the king that his coronal fell to the earth. And the king hit him again that he carved his belly and cut off his genitours, that his guts and his entrails fell down to the ground. Then the giant threw away his club, and caught the king in his arms that he crushed his ribs... And then Arthur weltered and wrung, that he was other while under and another time above. And so weltering and wallowing they rolled down the hill till they came to the sea mark, and ever as they so weltered Arthur smote him with his dagger.

Anthropophagicgiants are mentioned inThe Complaynt of Scotlandin 1549, the Opies note, and, inKing Learof 1605, they indicate,Shakespearealludes to theFee-fi-fo-fumchant ( "... fie, foh, and fumme, / I smell the blood of a British man" ), making it certain he knew a tale of "blood-sniffing giants".Thomas Nashealso alluded to the chant inHave with You to Saffron-Walden,written nine years beforeKing Lear;[3]the earliest version can be found inThe Red Ettinof 1528.[6]

Bluebeard

editThe Opies observe that "no telling of the tale has been recorded in English oral tradition", and that no mention of the tale is made in sixteenth or seventeenth century literature, lending weight to the probability of the tale originating from the oral traditions of the Cornish (and/or Breton) 'droll teller'.[7]The 17th century Franco-Breton tale ofBluebeard,however, contains parallels and cognates with the contemporary insular British tale of "Jack the Giant Killer", in particular the violentlymisogynisticcharacter of Bluebeard (La Barbe bleue,published 1697) is now believed to ultimately derive in part fromKing Mark Conomor,the 6th century continental (and probable insular) British King ofDomnonée/Dumnonia,associated in later folklore with bothCormoranofSt Michael's MountandMont Saint Michel– the blue beard (a 'Celtic' marker of masculinity) is indicative of his otherworldly nature.

The History of Jack and the Giants

edit"The History of Jack and the Giants" (the earliest known edition) was published in two parts by J. White ofNewcastlein 1711, the Opies indicate, but was not listed in catalogues or inventories of the period nor was Jack one of the folk heroes in the repertoire of Robert Powel (i.e.,Martin Powell), apuppeteerestablished inCovent Garden."Jack and the Giants" however is referenced inThe Weekly Comedyof 22 January 1708, according to the Opies, and in the tenth numberTerra-Filiusin 1721.[3]

As the eighteenth century wore on, Jack became a familiar figure. Research by the Opies indicate that the farceJack the Giant-Killerwas performed at theHaymarketin 1730; thatJohn Newberyprinted fictional letters about Jack inA Little Pretty Pocket-Bookin 1744; and that a political satire,The last Speech of John Good, vulgarly called Jack the Giant-Queller,was printed c. 1745.[3]The Opies and Bottigheimer both note thatHenry Fieldingalluded to Jack inJoseph Andrews(1742);Dr. Johnsonadmitted to reading the tale;Boswellread the tale in his boyhood; andWilliam Cowperwas another who mentioned the tale.[3][4]

In "Jack and Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant Killer", Thomas Green writes that Jack has no place in Cornish folklore, but was created at the beginning of the eighteenth century simply as a framing device for a series of gory, giant-killing adventures. The tales of Arthur precede and inform "Jack the Giant Killer", he notes, but points out thatLe Morte d'Arthurhad been out of print since 1634 and concludes from this fact that the public had grown weary of Arthur. Jack, he posits, was created to fill Arthur's shoes.[8]

Bottigheimer notes that in the southernAppalachiansof the United States, Jack became a generic hero of tales usually adapted from theBrothers Grimm.She points out however that "Jack the Giant Killer" is rendered directly from thechapbooksexcept the Englishhasty puddingin the incident of the belly-slashing Welsh giant becomesmush.[4]

Child psychologistBruno Bettelheimobserves inThe Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales(1976) that children may experience "grown-ups" as frightening giants, but stories such as "Jack" teach them that they can outsmart the giants and can "get the better of them". Bettelheim observes that a parent may be reluctant to read a story to a child about adults being outsmarted by children, but notes that the child understands intuitively that, in reading him the tale, the parent has given his approval for "playing with the idea of getting the better of giants", and of retaliating "in fantasy for the threat which adult dominance entails".[9]

British giants

editJohn Matthews writes inTaliesin: Shamanism and the Bardic Mysteries in Britain and Ireland(1992) that giants are very common throughout British folklore, and often represent the "original" inhabitants, ancestors, or gods of the island before the coming of "civilised man", their gigantic stature reflecting their "otherworldly"nature.[11]Giants figure prominently in Cornish, Breton and Welsh folklore, and in common with manyanimistbelief systems, they represent the force of nature.[citation needed]The modernStandard Written Formin Cornish isKowr[12]singular (mutatingtoGowr),Kewriplural, transcribed into Late Cornish asGour,"Goë", "Cor" or similar. They are often responsible for the creation of the natural landscape, and are oftenpetrifiedin death, a particularly recurrent theme inCeltic mythand folklore.[13]An obscure Count ofBrittanywas namedGourmaëlonruling from 908 to 913 and may be an alternative source of the Giant's nameCormoran,orGourmaillon,translated byJoseph Lothas "he of the brown eyebrows".[citation needed]

The foundation myth of Cornwall originates with the earlyBrythonicchroniclerNenniusin theHistoria Brittonumand made its way, via Geoffrey of Monmouth into Early Modern English canon where it was absorbed by theElizabethansas the tale ofKing Leiralongside that ofCymbelineandKing Arthur,other mythical British kings. Carol Rose reports inGiants, Monsters, and Dragonsthat the tale ofJack the Giant Killermay be a development of the Corineus and Gogmagog legend.[14]The motifs are echoed in theHunting of Twrch Trwyth.

In 1136,Geoffrey of Monmouthreported in the first book of his imaginativeThe History of the Kings of Britainthat the indigenous giants of Cornwall were slaughtered by Brutus, the (eponymousfounder of Great Britain), Corineus (eponymous founder ofCornwall) and his brothers who had settled in Britain after theTrojan War.Following the defeat of the giants, their leaderGogmagogwrestled with the warriorCorineus,and was killed when Corineus threw him from a cliff into the sea:

For it was a diversion to him [Corineus] to encounter the said giants, which were in greater numbers there than in all the other provinces that fell to the share of his companions. Among the rest was one detestable monster, named Goëmagot [Gogmagog], in stature twelvecubits[6.5 m], and of such prodigious strength that at one shake he pulled up an oak as if it had been a hazel wand. On a certain day, when Brutus (founder of Britain and Corineus' overlord) was holding a solemn festival to the gods, in the port where they at first landed, this giant with twenty more of his companions came in upon the Britons, among whom he made a dreadful slaughter. But the Britons at last assembling together in a body, put them to the rout, and killed them every one but Goëmagot. Brutus had given orders to have him preserved alive, out of a desire to see a combat between him and Corineus, who took a great pleasure in such encounters. Corineus, overjoyed at this, prepared himself, and throwing aside his arms, challenged him to wrestle with him. At the beginning of the encounter, Corineus and the giant, standing, front to front, held each other strongly in their arms, and panted aloud for breath, but Goëmagot presently grasping Corineus with all his might, broke three of his ribs, two on his right side and one on his left. At which Corineus, highly enraged, roused up his whole strength, and snatching him upon his shoulders, ran with him, as fast as the weight would allow him, to the next shore, and there getting upon the top of a high rock, hurled down the savage monster into the sea; where falling on the sides of craggy rocks, he was torn to pieces, and coloured the waves with his blood. The place where he fell, taking its name from the giant's fall, is called Lam Goëmagot, that is, Goëmagot's Leap, to this day.

The match is traditionally presumed to have occurred atPlymouth Hoeon the Cornish-Devonborder, althoughRame Headis a nearby alternative location. In the early seventeenth century,Richard Carewreported a carved chalk figure of a giant at the site in the first book ofThe Survey of Cornwall:

Againe, the activitie of Devon and Cornishmen, in this facultie of wrastling, beyond those of other Shires, dooth seeme to derive them a speciall pedigree, from that graund wrastler Corineus. Moreover, upon the Hawe at Plymmouth, there is cut out in the ground, the pourtrayture of two men, the one bigger, the other lesser, with Clubbes in their hands, (whom they terme Gog-Magog) and (as I have learned) it is renewed by order of the Townesmen, when cause requireth, which should inferre the same to bee a monument of some moment. And lastly the place, having a steepe cliffe adjoyning, affordeth an oportunitie to the fact.

Cormoran(sometimes Cormilan, Cormelian, Gormillan, or Gourmaillon) is the first giant slain by Jack.Cormoranand his wife, the giantessCormelian,are particularly associated withSt Michael's Mount,apparently an ancient pre-Christian site of worship. According to Cornish legend, the couple were responsible for its construction by carryinggranitefrom the West Penwith Moors to the current location of the Mount. When Cormoran fell asleep from exhaustion, his wife tried to sneak agreenschistslab from a shorter distance away. Cormoran awoke and kicked the stone out of her apron, where it fell to form the island of Chapel Rock.Trecobben,the giant ofTrencrom Hill(nearSt Ives), accidentally killed Cormelian when he threw a hammer over to the Mount for Cormoran's use. The giantess was buried beneath Chapel Rock.[14]

Blunderbore(sometimes Blunderboar, Thunderbore, Blunderbus, or Blunderbuss) is usually associated with the area ofPenwith,and was living in Ludgvan Lese (amanorinLudgvan), where he terrorised travellers heading north to St Ives. The Anglo-Germanicname 'Blunderbore' is sometimes appropriated by other giants, as in "Tom the Tinkeard"and in some versions of"Jack and the Beanstalk"and"Molly Whuppie".In the version of" Jack the Giant Killer "recorded byJoseph Jacobs,Blunderbore lives inPenwith,where he kidnaps three lords and ladies, planning to eat the men and make the women his wives. When the women refuse to consume their husbands in company with the giant, he hangs them by their hair in his dungeon and leaves them to starve. Shortly, Jack stops along the highway from Penwith to Wales. He drinks from a fountain and takes a nap (a device common in Brythonic Celtic stories, such as theMabinogion). Blunderbore discovers the sleeping Jack, and recognising him by his labelled belt, carries him to his castle and locks him in a cell. While Blunderbore is off inviting a fellow giant to come help him eat Jack, Jack creates nooses from some rope. When the giants arrive, he drops the nooses around their necks, ties the rope to a beam, slides down the rope, and slits their throats. A giant named Blunderbore appears in the similar Cornish fairy tale "Tom the Tinkeard"(or" Tom the Tinkard "), a local variant of"Tom Hickathrift".Here, Blunderbore has built a hedge over the King's Highway between St Ives andMarazion,claiming the land as his own. The motif of the abduction of women appears in this version, as Blunderbore has kidnapped at least twenty women to be his wives. The hero Tom rouses the giant from a nap while taking a wagon and oxen back from St Ives to Marazion. Blunderbore tears up an elm to swat Tom off his property, but Tom slides one of the axles from the wagon and uses it to fight and eventually fatally wound the giant. The dying giant confers all his wealth to Tom and requests a proper burial.

Thunderdellis a two-headed giant that crashes a banquet that is prepared for Jack.

Galligantusis a giant who holds captive many knights and ladies and a Duke's daughter who has been transformed into a white doe through the power of a sorcerer. Jack beheads the giant, the sorcerer flees, the Duke's daughter is restored to her true shape, and the captives are freed.

H. G. Wells

editin the 1904 novelThe Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth,H. G. Wellsdepicted the appearance of giants in the concrete reality of early 20th Century Britain. The giants arouse increasing hostility and prejudice, eventually leading to a rabble-rousing politician named Caterham forming an "Anti-Giant Party" and sweeping to power; the ambitious Caterham takes the nickname "Jack the Giant Killer", derived from the above tale. Unlike that tale, however, in Wells' depiction the giants are depicted sympathetically, as well-meaning innocents unjustly persecuted while the "Giant Killer" is the book's villain.

Adaptations

editFilms

edit1962 film

editIn 1962,United Artistsreleased a middle-budget film produced byEdward Smalland directed byNathan H. JurancalledJack the Giant Killer.Kerwin Mathewsstars as Jack andTorin Thatcheras the sorcerer Pendragon.

Jack the Giant Slayer

editThe filmJack the Giant Slayer,directed byBryan Singerand starringNicholas Houltwas produced byLegendary Picturesand was released on 1 March 2013. It is a very loose adaption of both "Jack and the Beanstalk" and "Jack the Giant Killer".[15]

2013 film

editThe direct-to video filmJack the Giant Killeris a 2013 Americanfantasy filmproduced byThe Asylumand directed by Mark Atkins. A modern take of the fairy talesJack the Giant KillerandJack and the Beanstalk,the film starsBen CrossandJane March.It is amockbusterofJack the Giant Slayer.It was released on DVD in the UK asThe Giant Killer.

Video game

editJack the Giantkilleris a 1982arcade gamedeveloped and published byCinematronics.It is based on the 19th-century English fairy taleJack and the Beanstalk.In Japan, the game was released asTreasure Hunt.[16]There were no home console ports.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^Davies 2007,p.[page needed].

- ^Gantz 1987,p. 80.

- ^abcdefgOpie & Opie 1992,pp. 47–50.

- ^abcZipes 2000,pp. 266–268.

- ^Armitage 2012,p.[page needed].

- ^Opie & Opie 1992,p. 78.

- ^O'Connor 2010,p.[page needed].

- ^Green 2009,pp. 1–4.

- ^Bettelheim 1977,pp. 27–28.

- ^"National Trust archaeologists surprised by likely age of Cerne Abbas Giant | National Trust".11 May 2021. Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2021.Retrieved25 February2024.

- ^Matthews 1992,p. 27.

- ^CLP staff,kowr

- ^Monaghan 2004,pp. 211–212.

- ^abRose 2001,p. 87.

- ^Flemming 2010.

- ^"Jack the Giantkiller".Gaming History.

References

edit- Armitage, Simon (2012).The Death of King Arthur.Faber & Faber.ISBN9780571249473.

- Bettelheim, Bruno(1977) [1976].The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales.Vintage Books.ISBN0-394-72265-5.

- CLP staff."kowr".cornish dictionary, gerlyver kernewek.Cornish Language Partnership.Retrieved1 February2015.

- Davies, Sioned (2007).The Mabinogion trans.[full citation needed]

- Gantz, Jeffrey (translator) (1987).The Mabinogion.New York: Penguin.ISBN0-14-044322-3.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Flemming, Kit (11 February 2010)."Nicholas Hoult To Star In 'Jack The Giant Killer'".Deadline Hollywood.Retrieved2 March2011.

- Green, Thomas (2009) [2007]."Jack and Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant Killer"(PDF).Thomas Green.

- Matthews, John (1992).Taliesin: Shamanism and the Bardic Mysteries in Britain and Ireland.The Aquarian Press.

- Monaghan, Patricia (2004).The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore.Facts on File.

- O'Connor, Mike (2010).Cornish Folk Tales.History Press Limited.ISBN9780752450667.

- Opie, Iona;Opie, Peter(1992) [1974].The Classic Fairy Tales.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-211559-6.

- Rose, Carol (2001).Giants, Monsters, and Dragons.W.W. Norton & Company.ISBN0-393-32211-4.

- Stafford, Jeff (2010)."Jack the Giant Killer".Turner Classic Movies.Retrieved1 December2010.

- Zipes, Jack,ed. (2000).The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-9653635-7-0.

Further reading

edit- Green, Thomas. "Tom Thumb and Jack the Giant-Killer: Two Arthurian Fairytales?" In:Folklore118 (2007): 123–140. DOI:10.1080/00155870701337296

- Weiss, Harry B. "The Autochthonal Tale of Jack the Giant Killer". The Scientific Monthly 28, no. 2 (1929): 126–33. Accessed 30 June 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/14578.

External links

edit- The History of the Kings of Britainby Geoffrey of Monmouth

- Jack the Giant Killerby Flora Annie Steel

- Jack the Giant Killerby Joseph Jacobs

- Jack the Giant Killerfrom the Hockliffe Collection

- Le Morte D'Arthurby Thomas MaloryArchived19 September 2005 at theWayback Machine

- The Story of Jack and the Giantsby Edward Dalziel

- The Survey of Cornwallby Richard Carew

- Tom the Tinkard

- Days of Yore: Jack the Giant-Killerby Arin Lee Kambitsis