"Howl",also known as"Howl for Carl Solomon",is a poem written byAllen Ginsbergin 1954–1955 and published in his 1956 collectionHowl and Other Poems.The poem is dedicated toCarl Solomon.

| Howl | |

|---|---|

| byAllen Ginsberg | |

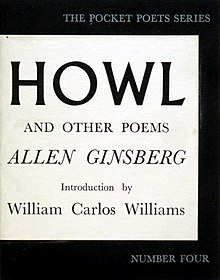

Howl and Other Poemswas published in the fall of 1956 as number four in thePocket Poets SeriesfromCity Lights Books. | |

| Written | 1955 |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Ginsberg began work on "Howl" in 1954. In the Paul Blackburn Tape Archive at theUniversity of California, San Diego,Ginsberg can be heard reading early drafts of his poem to his fellow writing associates. "Howl" is considered to be one of the great works of American literature.[1][2]It came to be associated with the group of writers known as theBeat Generation.[1]

Ginsberg read a draft of "Howl" at theSix Gallery readingin San Francisco in 1955. Fellow poetLawrence FerlinghettiofCity Lights Books,who attended the performance, published the work in 1956. Upon the poem's release, Ferlinghetti and the bookstore's manager,Shigeyoshi Murao,were charged with disseminatingobsceneliterature, and both were arrested. On October 3, 1957, Judge Clayton W. Horn ruled that the poem was not obscene.[3]

Writing

editAccording to Ginsberg's bibliographer and archivistBill Morgan,it was a terrifyingpeyotevision that was the principal inspiration forHowl.This occurred on the evening of October 17, 1954, in theNob Hillapartment of Sheila Williams, Ginsberg's girlfriend at that time, with whom he was living. Ginsberg had the terrifying experience of seeing the façade of theSir Francis Drake Hotelin the San Francisco fog as the monstrous face of a child-eating demon. Ginsberg took notes on his vision, and these became the basis for Part II of the poem.[4]

In late 1954 and 1955, in an apartment he had rented at 1010Montgomery Streetin theNorth Beachneighborhood of San Francisco, Ginsberg worked on the poem, originally referring to it by the working title "Strophes".[5]Some drafts were purportedly written at a coffeehouse calledCaffe MediterraneuminBerkeley, California;Ginsberg had moved into a small cottage in Berkeley a few blocks from the campus of the University of California on September 1, 1955.[6]Many factors went into the creation of the poem. A short time before the composition of "Howl", Ginsberg's therapist, Dr. Philip Hicks, encouraged him to realize his desire to quit his market-research job and pursue poetry full-time and to accept his own homosexuality.[7][8][9]He experimented with a syntactic subversion of meaning calledparataxisin the poem "Dream Record: June 8, 1955" about the death ofJoan Vollmer,a technique that became central in "Howl".[7][10]

Ginsberg showed this poem toKenneth Rexroth,who criticized it as too stilted and academic; Rexroth encouraged Ginsberg to free his voice and write from his heart.[11][12]Ginsberg took this advice and attempted to write a poem with no restrictions. He was under the immense influence ofWilliam Carlos WilliamsandJack Kerouacand attempted to speak with his own voice spontaneously.[12][13]Ginsberg began the poem in thestepped triadicform he took from Williams but, in the middle of typing the poem, his style altered such that his own unique form (a long line based on breath organized by a fixed base) began to emerge.[7][12]

Ginsberg experimented with this breath-length form in many later poems. The first draft contained what later became Part I and Part III.[citation needed]It is noted for relating stories and experiences of Ginsberg's friends and contemporaries, its tumbling, hallucinatory style, and the frank address of sexuality, specificallyhomosexuality,which subsequently provoked an obscenity trial. Although Ginsberg referred to many of his friends and acquaintances (includingNeal Cassady,Jack Kerouac,William S. Burroughs,Peter Orlovsky,Lucien Carr,andHerbert Huncke), the primary emotional drive was his sympathy forCarl Solomon,to whom it was dedicated; he had met Solomon in amental institutionand became friends with him.[citation needed]

Ginsberg later stated this sympathy for Solomon was connected to bottled-up guilt and sympathy for his mother'sschizophrenia(she had beenlobotomized), an issue he was not yet ready to address directly.[citation needed]In 2008, Peter Orlovsky told the co-directors of the 2010 filmHowlthat a short moonlit walk—during which Orlovsky sang a rendition of theHank Williamssong "Howlin' At the Moon"—may have been the encouragement for the title of Ginsberg's poem." I never asked him, and he never offered, "Orlovsky told them," but there were things he would pick up on and use in his verse form some way or another. Poets do it all the time. "[citation needed]The Dedication by Ginsberg states he took the title from Kerouac.[citation needed]

Performance and publication

editThe poem was first performed at theSix GalleryinSan Franciscoon October 7, 1955.[14]Ginsberg had not originally intended the poem for performance. The reading was conceived byWally Hedrick—a painter and co-founder of the Six—who approached Ginsberg in mid-1955 and asked him to organize a poetry reading at the Six Gallery. "At first, Ginsberg refused. But once he'd written a rough draft of Howl, he changed his 'fucking mind', as he put it."[15]

Ginsberg was ultimately responsible for inviting the readers (Gary Snyder,Philip Lamantia,Philip Whalen,Michael McClureandKenneth Rexroth) and writing the invitation. "Howl" was the second to last reading (before "A Berry Feast" by Snyder) and was considered by most in attendance the highlight of the reading. Many considered it the beginning of a new movement, and the reputation of Ginsberg and those associated with the Six Gallery reading spread throughout San Francisco.[15]In response to Ginsberg's reading, McClure wrote: "Ginsberg read on to the end of the poem, which left us standing in wonder, or cheering and wondering, but knowing at the deepest level that a barrier had been broken, that a human voice and body had been hurled against the harsh wall of America...."[16]

Jack Kerouac gave a first-hand account of the Six Gallery performance (in which Ginsberg is renamed 'Alvah Goldbrook' and the poem becomes 'Wail') in Chapter 2 of his 1958 novel,The Dharma Bums:

Anyway I followed the whole gang of howling poets to the reading at Gallery Six that night, which was, among other important things, the night of the birth of the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance. Everyone was there. It was a mad night. And I was the one who got things jumping by going around collecting dimes and quarters from the rather stiff audience standing around in the gallery and coming back with three huge gallon jugs of California Burgundy and getting them all piffed so that by eleven o'clock when Alvah Goldbrook was reading his poem 'Wail' drunk with arms outspread everybody was yelling 'Go! Go! Go!' (like a jam session) and old Rheinhold Cacoethes the father of the Frisco poetry scene was wiping his tears in gladness.[17]

Soon afterwards, "Howl" was published byLawrence Ferlinghetti,who ranCity Lights Bookstoreand theCity Lights Press.Ginsberg completed Part II and the "Footnote" after Ferlinghetti had promised to publish the poem. It was too short to make an entire book, so Ferlinghetti requested some other poems. Thus the final collection contained several other poems written at that time; with these poems, Ginsberg continued the experimentation with long lines and a fixed base he'd discovered with the composition of "Howl" and these poems have likewise become some of Ginsberg's most famous: "America","Sunflower Sutra ","A Supermarket in California",etc.[citation needed]

The earliest extant recording of "Howl" was thought to date from March 18, 1956, but in 2007 an earlier recording was found.[18]Ginsberg had read his poem at the Anna Mann dormitory atReed Collegeon February 13 and 14, with the second of those dates recorded. The tape was in excellent condition and was released by Omnivore Recordings in 2021.[19]In this recording, Ginsberg performs Part I of his poem. In the March 18 reading, in Berkeley, he performed all three parts.[20]

Overview and structure

editThe poem consists of 112 paragraph-like lines,[21]which are organized into three parts, with an additional footnote.

Part I

editCalled by Ginsberg "a lament for the Lamb in America with instances of remarkable lamb-like youths", Part I is perhaps the best known, and communicates scenes, characters, and situations drawn from Ginsberg's personal experience as well as from the community of poets, artists, politicalradicals,jazzmusicians,drug addicts,and psychiatric patients whom he had encountered in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ginsberg refers to these people, who were underrepresented outcasts in what the poet believed to be an oppressively conformist and materialistic era, as "the best minds of my generation". He describes their experiences in graphic detail, openly discussing drug use and homosexual activity at multiple points.

Most lines in this section contain the fixed base "who". In "Notes Written on Finally RecordingHowl",Ginsberg writes," I depended on the word 'who' to keep the beat, a base to keep measure, return to and take off from again onto another streak of invention ".[22]

Part II

editGinsberg says that Part II, in relation to Part I, "names the monster of mental consciousness that preys on the Lamb". Part II is about the state of industrial civilization, characterized in the poem as "Moloch".Ginsberg was inspired to write Part II during a period ofpeyote-induced visionary consciousness in which he saw a hotel façade as a monstrous and horrible visage which he identified with that of Moloch, theBiblicalidolinLeviticusto whom theCanaanitessacrificedchildren.[22]

Ginsberg intends that the characters he portrays in Part I be understood to have been sacrificed to this idol. Moloch is also the name of an industrial,demonicfigure inFritz Lang'sMetropolis,a film that Ginsberg credits with influencing "Howl, Part II" in his annotations for the poem (see especiallyHowl: Original Draft Facsimile, Transcript & Variant Versions). Most lines in this section contain the fixed base "Moloch". Ginsberg says of Part II, "Here the long line is used as astanzaform broken into exclamatory units punctuated by a base repetition, Moloch. "[22]

Part III

editPart III, in relation to Parts I, II and IV, is "a litany of affirmation of the Lamb in its glory", according to Ginsberg. It is directly addressed toCarl Solomon,whom Ginsberg met during a brief stay at a psychiatric hospital in 1949; called "Rockland"in the poem, it was actually Columbia Presbyterian Psychological Institute. This section is notable for its refrain," I'm with you in Rockland ", and represents something of a turning point away from the grim tone of the" Moloch "-section. Of the structure, Ginsberg says Part III is" pyramidal, with a graduated longer response to the fixed base ".[22]

Footnote

editThe closing section of the poem is the "Footnote", characterized by its repetitive "Holy!" mantra, an ecstatic assertion that everything is holy. Ginsberg says, "I remembered the archetypal rhythm of Holy Holy Holy weeping in a bus on Kearny Street, and wrote most of it down in notebook there.... I set it as 'Footnote to Howl' because it was an extra variation of the form of Part II."[22]

Rhythm

editThe frequently quoted and often parodied[23][24][25][26][27][excessive citations]opening lines set the theme and rhythm for the poem:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

Angel-headedhipstersburning for the ancient heavenly connection

to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

Ginsberg's own commentary discusses the work as an experiment with the "long line". For example, Part I is structured as a single run-on sentence with a repetitive refrain dividing it up into breaths. Ginsberg said, "Ideally each line of 'Howl' is a single breath unit. My breath is long—that's the measure, one physical-mental inspiration of thought contained in the elastic of a breath."[22]

On another occasion, he explained: "the line length... you'll notice that they're all built onbop—you might think of them as a bop refrain—chorus after chorus after chorus—the ideal being, say,Lester YounginKansas Cityin 1938, blowing 72 choruses of 'The Man I Love' until everyone in the hall was out of his head... "[28]

1957 obscenity trial

edit"Howl" contains many references to illicit drugs and sexual practices, bothheterosexualandhomosexual.Claiming that the book was obscene, customs officials seized 520 copies of the poem that were being imported from England on March 25, 1957.[29]

On June 3Shig Murao,the bookstore manager, was arrested and jailed for sellingHowl and Other Poemsto an undercover San Francisco police officer. City Lights publisherLawrence Ferlinghettiwas subsequently arrested for publishing the book. At the obscenity trial, nine literary experts testified on the poem's behalf. Ferlinghetti, a published poet himself, is credited (byDavid SkoverandRonald K. L. Collins) with breathing "publishing life" into Ginsberg's poetic career.[30]Supported by theAmerican Civil Liberties Union,Ferlinghetti won the case whenCalifornia State Superior CourtJudge Clayton Horn decided that the poem was of "redeeming social importance".[31][32]

The case was widely publicized, with articles appearing in bothTimeandLifemagazines. An account of the trial was published by Ferlinghetti's lead defense attorneyJake Ehrlichin a book calledHowl of the Censor.The 2010 filmHowldepicts the events of the trial.James Francostars as the young Allen Ginsberg and Andrew Rogers portrays Ferlinghetti.[33]

1969 broadcast controversy in Finland

editPart one of "Howl" was broadcast inFinlandon September 30, 1969, onYleisradio's (Finland's national public-broadcasting company) "parallel programme" at 10:30 p.m. The poem was read by three actors withjazz musicspecially composed for this radio broadcast byHenrik Otto Donner.The poem was preceded by an eight-minute introduction. TheFinnishtranslation was made byAnselm Hollo.[34]The translation was published already in 1961 inParnassoliterary magazine, and caused no turmoil then.[citation needed]

ALiberal People's Partymember of theFinnish Parliament,Arne Berner,heard the broadcast, and started aninterpellation,addressed to the Minister of Transport and Public Works. It was signed by him and 82 of the 200 members of parliament.[35]It is unclear how many of the other signatories actually had heard the broadcast. The interpellation text only contained a short extract of six lines (considered to be offensive, and representative of the poem) of over seventy from the poem, and the debate was mainly based upon them.[36]

Also, a report of an offence was filed to the criminal investigation department ofHelsinkipolice district because theobscenityof the poem allegedly offended modesty and delicacy. The report was filed by Suomen kotien radio- ja televisioliitto (The radio and television association of Finnish homes), a Christian and patriotic organization, and it was only based on the six-line fragment. In connection with that, Yleisradio was accused ofcopyright violation.[37]No charges followed.[citation needed]

At that time, homosexual actswere still illegal in Finland.[citation needed]

Finally, the Ministry of Transport and Public Works considered in December 1969 that the broadcast of "Howl" contravened the licence of operation of Yleisradio: it was neither educational nor useful. Yleisradio received areprimand,and was instructed to be more careful when monitoring that no more such programs should be broadcast.[38]

Biographical references and allusions

editPart I

edit| Line | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| "who bared their brains to Heaven under the El and sawMohammedanangels staggering on tenement roofs illuminated. " | This is a direct reference to a story told to Ginsberg by Kerouac about poetPhilip Lamantia's "celestial adventure" after reading theQuran.[39] | |

| "Who passed through universities with radiant cool eyes hallucinatingArkansasandBlake—light tragedies among the scholars of war "and" who thought they were only mad whenBaltimoregleamed in supernatural ecstasy " | Ginsberg had an auditory hallucination in 1948 of William Blake reading his poems "Ah, Sunflower", "The Sick Rose", and "Little Girl Lost". Ginsberg said it revealed to him the interconnectedness of all existence. He said his drug experimentation in many ways was an attempt to recapture that feeling.[40][41] | |

| "Who were expelled from the academy for crazy & publishing obscene odes on the windows of the skull" | Part of the reason Ginsberg was suspended in his sophomore year[42][full citation needed]fromColumbia Universitywas because he wrote obscenities in his dirty dorm window. He suspected the cleaning woman of being ananti-Semitebecause she never cleaned his window, and he expressed this feeling in explicit terms on his window, by writing "Fuck the Jews", and drawing aswastika.He also wrote a phrase on the window implying that the president of the university had notesticles.[43][44] | |

| "who cowered in unshaven rooms in underwear, burning their money in wastebaskets and listening to the Terror through the wall" | Lucien Carrburned his insanity record, along with $20, at his mother's insistence.[45] | |

| "... poles of Canada andPaterson... " | Kerouac wasFrench-CanadianfromLowell, Massachusetts;Ginsberg grew up in Paterson, New Jersey.[46] | |

| "who sank all night in submarine light of Bickford's floated out and sat through the stale beer afternoons in desolate Fugazzi's..." | Bickford'sand Fugazzi's were New York spots where the Beats hung out. Ginsberg worked briefly at Fugazzi's.[47][48] | |

| "... Tangerian bone-grindings..." "... Tangiers to boys..." and "Holy Tangiers!" | William S. Burroughs lived inTangier, Moroccoat the time Ginsberg wrote "Howl". He also experienced withdrawal fromheroin,which he wrote about in several letters to Ginsberg.[49] | |

| "who studiedPlotinusPoeSt. John of the Crosstelepathyandbopkabbalahbecause the cosmos instinctively vibrated at their feet inKansas" | Mystics and forms of mysticism in which Ginsberg at one time had an interest.[49] | |

| "who disappeared into the volcanoes of Mexico". | Both a reference to John Hoffman, a friend of Philip Lamantia and Carl Solomon, who died in Mexico, and a reference toUnder the VolcanobyMalcolm Lowry.[39] | |

| "weeping and undressing while the sirens of Los Alamos wailed them down" | A reference to a protest staged byJudith Malina,Julian Beck,and other members ofThe Living Theatre.[50] | |

| "who bit detectives in the neck... dragged off the roof waving genitals and manuscripts." Also, from "who... fell out of the subway window" to "the blast of colossal steam whistles". | A specific reference toBill Cannastra,who actually did most of these things and died when he "fell out of the subway window".[50][51][52] | |

| "Saintly motorcyclists" | A reference toMarlon Brandoand his biker persona inThe Wild One.[49] | |

| From "Who copulated ecstatic and insatiate" to "Who went out whoring throughColoradoin myriad stolen night-cars, N. C. secret hero of these poems ". Also, from" who barreled down the highways of the past "to" & nowDenveris lonesome for her heroes " | A reference toNeal Cassady(N.C.) who lived in Denver, Colorado, and had a reputation for being sexually voracious, as well as stealing cars.[53][54][55] | |

| "who walked all night with their shoes full of blood on the showbank docks waiting for a door in theEast Riverto open to a room full of steamheat andopium" | A specific reference toHerbert Huncke's condition after being released fromRiker's Island.[54][56] | |

| "... and rose to build harpsichords in their lofts..." | FriendBill Keckbuilt harpsichords. Ginsberg had a conversation with Keck's wife shortly before writing "Howl".[51][57][58] | |

| "who coughed on the sixth floor ofHarlemcrowned with flame under the tubercular sky surrounded by orange crates of theology " | This is a reference to the apartment in which Ginsberg lived when he had his Blake vision. His roommate, Russell Durgin, was a theology student and kept his books in orange crates.[57][59] | |

| "who threw their watches off the roof to cast their ballot with eternity outside of time..." | A reference to Ginsberg's Columbia classmateLouis Simpson,an incident that happened during a brief stay in a mental institution forpost-traumatic stress disorder.[54][57] | |

| "who were burned alive in their innocent flannel suits onMadison Avenue... thenitroglycerineshrieks of the fairies of advertising " | Ginsberg worked as a market researcher for Towne-Oller Associates in San Francisco, on Montgomery Street, not Madison Avenue.[60] | |

| "who jumped off theBrooklyn Bridge... " | A specific reference toTuli Kupferberg.[50][61] | |

| "who crashed through their minds in jail..." | A reference toJean Genet'sLe Condamné à mort(poem translated as "The Man Sentenced to Death" ).[50] | |

| "who retired to Mexico to cultivate a habit, or Rocky Mount to tenderBuddhaor Tangiers to boys orSouthern Pacificto the black locomotive orHarvardtoNarcissusto Woodlawn to the daisychain or grave " | Many of the Beats went to Mexico City to "cultivate" a drug "habit", but Ginsberg claims this is a direct reference to Burroughs and Bill Garver, though Burroughs lived in Tangiers at the time[62](as Ginsberg says in "America": "Burroughs is in Tangiers I don't think he'll come back it's sinister"[63]).Rocky Mount, North Carolina,is where Jack Kerouac's sister lived (as recounted inThe Dharma Bums).[64]Also, Neal Cassady was a brakeman for the Southern Pacific.John Hollanderwas an alumnus of Harvard. Ginsberg's mother Naomi lived nearWoodlawn Cemetery.[55][57] | |

| "Accusing the radio of hypnotism..." | A reference to Ginsberg's mother Naomi, who suffered fromparanoid schizophrenia.It also refers toAntonin Artaud's reaction toshock therapyand his "To Have Done with the Judgement of God", which Solomon introduced to Ginsberg at Columbia Presbyterian Psychological Institute.[65][66] | |

| From "who threw potato salad at CCNY lecturers onDadaism... "to" resting briefly incatatonia" | A specific reference to Carl Solomon. Initially this final section went straight into what is now Part III, which is entirely about Carl Solomon. Dadaism is an art movement emphasizing nonsense and irrationality. In the poem, it is the subject of a lecture that is interrupted by students throwing potato salad at the professors. This ironically mirrored the playfulness of the movement but in a darker context. A Post WW1 cultural movement, Dada stood for 'anti-art', it was against everything that art stood for. Founded in Zurich, Switzerland. The meaning of the word means two different definitions; "hobby horse" and "father", chosen randomly. The Dada movement spread rapidly.[67][68][69] | |

| "Pilgrim's State's Rockland's and Greystone's foetid halls..." and "I'm with you in Rockland" | These are mental institutions associated with either Ginsberg's mother Naomi or Carl Solomon: Pilgrim State Hospital and Rockland State Hospital in New York andGreystone Park Psychiatric HospitalinNew Jersey.Ginsberg met Solomon at Columbia Presbyterian Psychological Institute, but "Rockland" was frequently substituted for "rhythmic euphony".[65][66][70] | |

| "with mother finally ******" | Ginsberg admitted that the deletion here was an expletive. He left it purposefully elliptical "to introduce appropriate element of uncertainty". In later readings, many years after he was able to distance himself from his difficult history with his mother, he reinserted the word "fucked".[67] | |

| "obsessed with a sudden flash of thealchemyof the use of the ellipse the catalog the meter (alt: variable measure) & the vibrating plane ". Also, from" who dreamt and made incarnate gaps in Time & Space "to" what might be left to say in time come after death ". | This is a recounting of Ginsberg's discovery of his own style and the debt he owed to his strongest influences. He discovered the use of the ellipse fromhaikuand the shorter poetry ofEzra PoundandWilliam Carlos Williams."The catalog" is a reference to Walt Whitman's long line style which Ginsberg adapted. "The meter" / "variable measure" is a reference to Williams' insistence on the necessity of measure. Though "Howl" may seem formless, Ginsberg claimed it was written in a concept of measure adapted from Williams' idea of breath, the measure of lines in a poem being based on the breath in reading. Ginsberg's breath in reading, he said, happened to be longer than Williams'. "The vibrating plane" is a reference to Ginsberg's discovery of the "eyeball kick" in his study of Cézanne.[71][72][73] | |

| "Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus" / "omnipotent, eternal father God" | This was taken directly fromCézanne.[65][74] | |

| "to recreate the measure and syntax of poor human prose..." | A reference to the tremendous influence Kerouac and his ideas of "Spontaneous Prose" had on Ginsberg's work and specifically this poem.[75][76] | |

| "what might be left to say in time come after death" | A reference toLouis Zukofsky's translation ofCatullus:"What might be left to say anew in time after death..." Also a reference to a section from the final pages ofVisions of Cody,"I'm writing this book because we're all going to die", and so on.[65] | |

| "eli eli lama sabachthani" | One of thesayings of Jesus on the cross,alsoPsalm 22:1: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" The phrase in Psalms was transliterated as "azavtani"; however, Ginsberg stayed true to how Jesus translated the phrase in the Gospels. The phrase used by Ginsberg was translated properly as "Why have you sacrificed me?" This ties into the themes of misfortune and religious adulation of conformity through the invocation of Moloch in Part II. Though Ginsberg grew up in anagnostichousehold, he was very interested in his Jewish roots and in other concepts of spiritual transcendence. Although later Ginsberg was a devoted Buddhist, at this time he was only beginning to study Buddhism along with other forms of spirituality.[57] | |

Part II

edit| Line | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| "Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness!" | Fire god of theCanaanitesreferred to inLeviticus 18:21:"And thou shalt not let any of thy seed pass through the fire to Molech." Worship of Moloch involved the sacrifice of children by fire.[58][77] | |

| "Moloch whose buildings are judgement!" | A reference toUrizen,one ofWilliam Blake's fourZoas.[77] | |

| "Crossbone soulless jailhouse and congress of sorrows..." and "Holy the solitudes of skyscrapers and pavements! Holy the cafeterias filled with the millions!" | A reference toGods' Man,agraphic novelbyLynd Wardwhich was in Ginsberg’s childhood library.[78] | |

| From "Moloch whose breast is acannibaldynamo! "to" Moloch whose skyscrapers stand in the long streets like endlessJehovahs!" | A reference to several films byFritz Lang,most notablyMetropolisin which the name "Moloch" is directly related to a monstrous factory. Ginsberg also claimed he was inspired by Lang'sMandThe Testament of Dr. Mabuse.[79] | |

| "Moloch whose eyes are a thousand blind windows!" | Ginsberg claimed Part II of "Howl" was inspired by a peyote-induced vision of the Sir Francis Drake Hotel in San Francisco which appeared to him as a monstrous face.[51][79][80] | |

| From "Moloch whose soul is electricity and banks!" to "Moloch whose name is the Mind!" | A reference toEzra Pound's idea ofusuryas related in theCantosand ideas from Blake, specifically the "Mind forg'd manacles" from "London". Ginsberg claimed "Moloch whose name is the Mind!" is "a crux of the poem".[81] | |

| "Lifting the city toHeavenwhich exists and is everywhere about us " | A reference to "Morning" fromSeason in HellbyArthur Rimbaud.[81] | |

Part III

edit| Line | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| "I'm with you in Rockland/where we are great writers on the same dreadful typewriter..." | At Columbia Presbyterian Psychological Institute, Ginsberg and Solomon wrote satirical letters toMalcolm de ChazalandT. S. Eliotwhich they did not ultimately send.[82][83] | |

| "I'm with you in Rockland/where you drink the tea of the breasts of the spinsters of Utica." | A reference toMamelles de TiresiasbyGuillaume Apollinaire.[84] | |

| From "I'm with you in Rockland/where you scream in a straightjacket" to "fifty more shocks will never return your soul to its body again..." | Solomon received shock treatment and was put in a straightjacket at Pilgrim State.[84] | |

| "I'm with you in Rockland/where you bang on a catatonic piano..." | Ginsberg was the one reprimanded for banging on a piano at CPPI.[85][86] | |

| "I'm with you in Rockland/where you split the heavens ofLong Island... " | Pilgrim State is located on Long Island.[85] | |

| "I'm with you in Rockland/where there are twenty five thousand mad comrades all together singing the final stanzas ofthe Internationale... " | The population of Pilgrim State was 25,000. "The Internationale"was a song used and made popular by worker movements, and was featured in theLittle Red Songbookof theIndustrial Workers of the World.[85] | |

| "... the door of my cottage in the Western night." | A reference to the cottage on Milvia Street in Berkeley, California, where many of the poems inHowl and Other Poemswere composed, including "A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley".[85] | |

Footnote to "Howl"

edit| Line | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| "Everyday is in eternity!" | A reference to "Auguries of Innocence"by Blake:" Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/And Eternity in an hour.”[87] | |

| "Holy Peter holy Allen holy Solomon holy Lucien holy Kerouac holy Huncke holy Burroughs holy Cassady..." | Peter Orlovsky,Allen Ginsberg,Carl Solomon,Lucien Carr,Jack Kerouac,Herbert Huncke,William S. Burroughs,andNeal Cassady.[87] | |

| "Holy the Fifth International" | A reference to four "Internationals", meetings ofCommunist,Socialist,and/orLaborgroups. TheFirst Internationalwas headed byKarl MarxandFrederick Engelsin 1864. TheFourth Internationalwas a meeting ofTrotskyistsin 1938. The Fifth International, Ginsberg would claim, is yet to come.[87] | |

Critical reception

editThe New York TimessentRichard EberharttoSan Franciscoin 1956 to report on the poetry scene there. The result of Eberhart's visit was an article published in the September 2, 1956New York Times Book Reviewtitled "West Coast Rhythms". Eberhart's piece helped call national attention to "Howl" as "the most remarkable poem of the young group" of poets who were becoming known as the spokespersons of theBeat generation.[88]

On October 7, 2005, celebrations marking the 50th anniversary of the first reading of the poem were staged in San Francisco, New York City, and inLeedsin the UK. The British event, Howl for Now, was accompanied by a book of essays of the same name, edited by Simon Warner and published by Route Publishing (Howl for NowISBN1-901927-25-3) reflecting on the piece's enduring influence.

1997 broadcasting controversy

editBostonindependent alternative rock radio stationWFNXbecame the first commercial radio station to broadcast "Howl" on Friday, July 18, 1997, at 6:00 p.m. despiteFederal Communications Commission(FCC)Safe Harborlaws which allow for mature content later at night.[89][90]

2007 broadcasting fears

editIn late August 2007, Ron Collins, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Nancy Peters, Bill Morgan, Peter Hale, David Skover,Al Bendich(one of Ferlinghetti's lawyers in the 1957 obscenity trial), and Eliot Katz petitionedPacifica Radioto air Ginsberg'sHowlon October 3, 2007, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the verdict declaring the poem to be protected under theFirst Amendmentagainst charges of obscenity. Fearing fines from the FCC, Pacifica New York radio stationWBAIopted not to broadcast the poem. The station chose instead to play the poem on a specialwebcastprogram, replete with commentary (by Bob Holman, Regina Weinreich and Ron Collins, narrated by Janet Coleman), on October 3, 2007.[91]

Legacy

editPart II of the poem was used as libretto for Song #7 inHydrogen Jukebox,a 1990chamber operausing a selection of Ginsberg's poems set to music byPhilip Glass.[92]The title itself comes from the poem: "...listening to the crack of doom on the hydrogen jukebox..."[93] The first line of the poem, "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical..." was also used as the opening line in the song "I Should Be Allowed To Think"byThey Might Be Giants.

Film

editThe 2010 filmHowlexplored Ginsberg's life and works. Constructed in anonlinearfashion, the film juxtaposes historical events with a variety ofcinematic techniques.It reconstructs theearly life of Ginsberg during the 1940s and 1950s.It also re-enacts Ginsberg's debut performance of "Howl" at theSix Gallery Readingon October 7, 1955, in black-and-white.[94]Parts of the poem are interpreted through animated sequences, and the events are juxtaposed with color images of Ferlinghetti's 1957 obscenity trial.

References

edit- ^abBill Savage (2008).Allen Ginsberg's "Howl" and the Paperback RevolutionArchived2011-09-05 at theWayback Machine.Poets.org, Academy of American Poets.

- ^Jonah Raski (2006).American Scream: Allen Ginsberg's Howl and the Making of the Beat Generation.University of California Press. 223.

- ^Morgan, Bill and Joyce Peters.Howl on Trial.(2006) p. xiii.

- ^Bill Morgan,The Typewriter Is Holy: Complete, Uncensored History of the Beat Generation(New York: Free Press, 2010), pp. 86–87. In the introduction Morgan says: "[F]or the last two decades of Allen Ginsberg's life, I assisted him daily as his bibliographer and archivist. During that period, I managed to track down nearly everything that he had ever published and a good deal of what had been printed about him. It was a mammoth task. Every day, as I walked to the apartment that served both as Allen's home and office, I wondered what new treasures I'd uncover.... After I sold his archive to Stanford University for a million dollars, Allen referred everyone with questions about their papers to me" (p. xvi).

- ^Morgan,The Typewriter Is Holy(2010), pp. 92 & 96.

- ^Morgan,The Typewriter Is Holy(2010), p. 97.

- ^abcAllen Ginsberg.Journals Mid-Fifties: 1954–1958.Ed. Gordon Ball. HarperCollins, 1995. 0060167718.

- ^James Breslin. "Allen Ginsberg: The Origins ofHowlandKaddish."Poetry Criticism.Ed. David M. Galens. Vol. 47. Detroit: Gale, 2003.

- ^Morgan,The Typewriter Is Holy(2010), p. 92

- ^Miles, Barry.Ginsberg: A Biography.London: Virgin Publishing Ltd. (2001), paperback, 628 pages,ISBN0-7535-0486-3,p. 182

- ^Journals Mid-Fifties,p. 9

- ^abcMiles, p. 183

- ^Journals Mid-Fifties,p. 167

- ^Heidi Benson, "Howl",San Francisco Chronicle ", October 4, 2005

- ^abJonah Raskin,American Scream: Allen Ginsberg's "Howl" and the Making of the Beat Generation

- ^Poets.org, From the Academy of American Poets:Allen Ginsberg

- ^Kerouac, Jack (1994).The Dharma Bums.Great Britain: Phoenix Harpercollins. p. 15.ISBN0586091580.

- ^Suiter, John (December 1, 2008)."When The Beats Came Back".Reed Magazine.

- ^"Allen Ginsberg: At Reed College: The First Recorded Reading Of Howl & Other Poems".Omnivore Recordings.

- ^Suiter, John."When The Beats Came Back".Reed Magazine.

- ^Poetry Across the Curriculum: New Methods of Writing Intensive Pedagogy for U.S. Community College and Undergraduate Education.Brill. 2018.ISBN978-90-04-38067-7.

- ^abcdefGinsberg, Allen. "Notes Written on Finally Recording 'Howl.'"Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays 1952–1995.Ed. Bill Morgan. New York: Harper Collins, 2000.

- ^"'Howl' at the Internet ".

- ^Scoville, Thomas."Howl.com".

- ^Lowry, Brigid (2006).Guitar Highway Rose.Macmillan.ISBN9780312342968– via Google Books.

- ^Colagrande, J. J. (19 February 2014).""PROWL", a Parody on Miami's Transience and Eccentricities ".HuffPost.

- ^Felber, Katie (25 August 2014)."I Re-Wrote Ginsberg's 'Howl' for This Generation".HuffPost.

- ^Jeff Baker,"'Howl' tape gives Reed claim to first"Archived2008-02-13 at theWayback Machine,The Oregonian,2008-02-12

- ^Miles, Barry (March 18, 2019)."The Beat Goes On A century of Lawrence Ferlinghetti".Poetry Foundation.RetrievedDecember 2,2019.

- ^Collins, Ronald K. L.;Skover, David(2019).The People v. Ferlinghetti: The Fight to Publish Allen Ginsberg's Howl.Rowman & Littlefield. p. xi.ISBN9781538125908.

- ^How "Howl" Changed the World,Allen Ginsberg's anguished protest broke all the rules—and encouraged a generation of artists to do the same. ByFred Kaplan,Slate, Sept. 24, 2010

- ^Ferlinghetti, Lawrence (1984)."Horn on Howl".In Lewis Hyde (ed.).On the poetry of Allen Ginsberg.University of Michigan Press. pp.42–53.ISBN0-472-06353-7.

- ^Scott, A. O.(September 23, 2010)."Howl (2010)".The New York Times.

- ^Lounela, Pekka & Mäntylä, Jyrki:Huuto ja meteli,p. 16. [Howl and turmoil.] Hämeenlinna, Karisto. 1970. (In Finnish.)

- ^Lounela & Mäntylä, p. 17.

- ^Lounela & Mäntylä, p. 102.

- ^Lounale & Mäntylä, pp. 39–41.

- ^Lounela & Mäntylä, pp. 5, 78–79.

- ^abAllen Ginsberg. "Howl: Original Draft Facsimile, Transcript & Variant Versions, Fully Annotated by Author, with Contemporaneous Correspondence, Account of First Public Reading, Legal Skirmishes, Precursor Texts & Bibliography". Ed. Barry Miles. Harper Perennial, 1995.ISBN0-06-092611-2.p. 124.

- ^Original Draft,pp. 125, 128

- ^Lewis Hyde.On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg.University of Michigan Press, 1984ISBN978-0-472-06353-6,p. 6.

- ^Lib.unc.edu

- ^Original Draft,p. 132

- ^Miles, p. 57

- ^Allen Ginsberg.The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice: First Journals and Poems 1937–1952.Ed. Juanita Lieberman-Plimpton and Bill Morgan. Da Capo Press, 2006.ISBN0-306-81462-5.p. 58.

- ^Miles, p. 1

- ^Original Draft,p. 125

- ^Raskin, p. 134

- ^abcOriginal Draft,p. 126

- ^abcdOriginal Draft,p. 128

- ^abcMiles, p. 189

- ^Bill Morgan.I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg.Penguin, 2006.ISBN978-0-14-311249-5,p. 128.

- ^Original Draft,p. 126–127

- ^abcMiles, p. 186

- ^abRaskin, p. 137

- ^Original Draft,p. 133

- ^abcdeOriginal Draft,p. 134

- ^abHowl on Trial,p. 34

- ^Miles, p. 97

- ^Journals Mid-Fifties,p. 5

- ^Raskin, p. 135

- ^Allen Hibbard.Conversations with William S. Burroughs.University Press of Mississippi, 2000.ISBN1-57806-183-0.p. xix.

- ^Allen Ginsberg. "America".Howl and Other Poems.City Lights Publishers, 2001.ISBN0-87286-017-5.p. 38.

- ^David Creighton.Ecstasy of the Beats: On the Road to Understanding.Dundurn, 2007.ISBN1-55002-734-4.p. 229.

- ^abcdOriginal Draft,p. 130

- ^abMatt Theado.The Beats: A Literary Reference.Carroll & Graf, 2003.ISBN0-7867-1099-3.p. 53

- ^abOriginal Draft,p. 131

- ^Miles, pp. 117, 187

- ^Morgan, p. 118

- ^Morgan, p. 13

- ^Original Draft,pp. 130–131

- ^Miles, p. 187

- ^Allen Ginsberg. "A Letter to Eberhart".Beat Down to Your Soul.Ed. Ann Charters. Penguin, 2001.ISBN0-14-100151-8,p. 121.

- ^Hyde, p. 2

- ^Original Draft,p. 136

- ^Allen Ginsberg.Spontaneous Mind: Selected Interviews 1958–1996.Ed. David Carter. Perennial, 2001, p. 291

- ^abOriginal Draft,p. 139

- ^Original Draft,pp. 139, 146

- ^abOriginal Draft,p. 140

- ^Morgan, p. 184

- ^abOriginal Draft, p. 142

- ^Original Draft,p. 143

- ^Theado, p. 242

- ^abOriginal Draft,p. 144

- ^abcdOriginal Draft,p. 145

- ^Miles, p. 121

- ^abcOriginal Draft,p. 146

- ^Original Draftp. 155

- ^"Allen Ginsberg's 'Howl': a groundbreaking performance".Boston Phoenix.July 17, 1997. Archived fromthe originalon February 9, 1999.RetrievedOctober 16,2012.

- ^"WFNX On Demand: The Best of 1997".WFNX.Archived fromthe originalon October 17, 2012.RetrievedOctober 16,2012.

- ^Garofoli, Joe (October 3, 2007)."'Howl' too hot to hear ".San Francisco Chronicle.Archived fromthe originalon November 25, 2009.RetrievedJanuary 22,2010.

- ^Thomas Rain Crowe (1997)."Hydrogen Jukebox (1990)".In Kostelanetz, Richard; Flemming, Robert (eds.).Writings on Glass: Essays, Interviews, Criticism.University of California Press. pp. 249–250.ISBN9780520214910.Retrieved23 October2016.

- ^"Hydrogen Jukebox – Philip Glass".Retrieved3 May2024.

- ^"'Howl' filmmakers talk youth culture, James Franco ".Archived fromthe originalon 2014-04-29.Retrieved2021-08-12.

Further reading

edit- Collins, Ronald & Skover, David.Mania: The Story of the Outraged & Outrageous Lives that Launched a Cultural Revolution(Top-Five Books, March 2013)

- Charters, Ann (ed.).The Portable Beat Reader.Penguin Books. New York. 1992.ISBN0-670-83885-3(hc);ISBN0-14-015102-8(pbk)

- Ginsberg, Allen.Howl.1986 critical edition edited by Barry Miles,Original Draft Facsimile, Transcript & Variant Versions, Fully Annotated by Author, with Contemporaneous Correspondence, Account of First Public Reading, Legal Skirmishes, Precursor Texts & BibliographyISBN0-06-092611-2(pbk.)

- Howl of the Censor.Jake Ehrlich,Editor.ISBN978-0-8371-8685-6

- Lounela, Pekka – Mäntylä, Jyrki:Huuto ja meteli.[Howl and turmoil.] Hämeenlinna, Karisto. 1970.

- Miles, Barry.Ginsberg: A Biography.London: Virgin Publishing Ltd. (2001), paperback, 628 pages,ISBN0-7535-0486-3

- Raskin, Jonah.American Scream: Allen Ginsberg's "Howl" and the Making of the Beat Generation.Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.ISBN0-520-24015-4

External links

edit- Allen Ginsberg.org

- The Poetry Archive: Allen Ginsberg

- Allen Ginsberg on Poets.orgWith audio clips, poems, and related essays, from the Academy of American Poets

- Full text of "Howl"and"Footnote to Howl"at the Poetry Foundation

- Allen Ginsberg reads Howl. 27 minutes of audio.

- Naropa Audio Archives: Allen Ginsberg class (August 6, 1976)Streaming audio and 64 kbit/s MP3 ZIP

- Naropa Audio Archives: Anne Waldman and Allen Ginsberg reading, including Howl (August 9, 1975)Streaming audio and 64 kbit/s MP3 ZIP

- Allen Ginsberg Live in London – live film from October 19, 1995

- After 50 Years, Ginsberg's "Howl" Still Resonates

- Reading of Howl and other poems at Reed College, Portland, Oregon, February 1956Archived2015-09-06 at theWayback Machine

- Howls of Anger, and of LiberationbyThe Nation

- "Howl for Carl Solomon", manuscript and typescript, with autograph corrections and annotations,Stanford Digital Repository