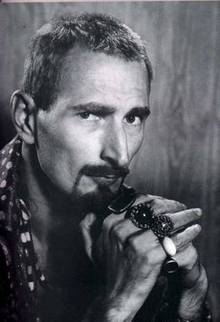

Jack Smith(November 14, 1932 – September 18, 1989) was an American filmmaker, actor, and pioneer ofunderground cinema.He is generally acclaimed as a founding father of Americanperformance art,and has been critically recognized as a masterphotographer.[1]

Jack Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 14, 1932 Columbus, Ohio,U.S. |

| Died | September 18, 1989(aged 56) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Filmmaker, actor, photographer |

| Known for | Flaming Creatures(1963) |

Life and career

editSmith was raised inTexas,where he made his first film,Buzzards over Baghdad,[2]in 1952. He moved toNew York Cityin 1953.[3]

The most famous of Smith's productions isFlaming Creatures(1963). The film, that first putcampon the map, is asatireof HollywoodB moviesand tribute to actressMaria Montez,who starred in many such productions. However, authorities considered some scenes to be pornographic. Copies of the movie were confiscated at the premiere, and it was subsequently banned from public view. Despite not being viewable, the movie gained some anti-heroic notoriety when footage was screened during Congressional hearings and right-wing politicianStrom Thurmondmentioned it in anti-porn speeches.

Smith's next movieNormal Love(akaNormal Fantasy, Exotic Landlordism of Crab Lagoon,andThe Great Pasty Triumph) (1963–1964) was the only work in Smith's oeuvre with an almost conventional length (120 mins.), and featured multiple underground stars, includingMario Montez,Diane di Prima,Tiny Tim,Francis Francine,Beverly Grant,John Vaccaro, and others. The rest of his productions consists mainly of short movies, many never screened in a cinema, but featured in performances and constantly re-edited to fit the stage needs (includingNormal Love).

After his last completed film,No President(1967), (Smith’s follow-up film,Sinbad In the Rented World(1972–1984) was never completed) he created smallintermediaperformance and experimental theatre work until his death on September 18, 1989, fromAIDS-related pneumonia.[4]Smith produced many theatrical mini-productions, often usingslide projectors,in his loft and in art space settings such asArtists SpaceandColab'sThe Times Square Show.Descriptors oflobstersas greedylandlordsdominate, along withcrabs,Atlantis,1950sexoticamusic, and camp-glamorousNorth Africancostumes. A pungent odor of burningincenseandmarijuanaoften perfumed the performances.

Apart from appearing in his own work, Smith worked as anactor.He played the lead inAndy Warhol's unfinished filmBatman Dracula,[5]Ken Jacobs'sBlonde Cobra,and appeared in several theater productions byRobert Wilson.

Smith also worked as aphotographerand founded the Hyperbole Photographic Studio in New York City. In 1962, he releasedThe Beautiful Book,a collection of pictures of New York artists, that was re-published in facsimile by Granary Books in 2001. As adraftsman,hisposters,hand written scripts and drawing-notes superimpose a very eccentric personal imagery onto the traditional language of theater.[6]

In 1978,Sylvère Lotringerconducted a 13-page interview with Smith (with photos) inColumbia University'sphilosophydepartment publication ofSemiotext(e).It was collected in 2013 inSchizo-Culture: The Event, The Book.[7]In 2014, it was released as a limited-ledition vinyl picture disc by Semiotext(e).

In 1987, Smith was awarded an honoraryDoctor of Humane Letters(L.H.D.) degree fromWhittier College.[8]

Estate

editIn 1989, New York performance artistPenny Arcadetried to salvage Smith's work from his apartment after his long bout with AIDS and subsequent death. Arcade attempted to preserve the apartment as Smith had transformed it – an elaborate stage set for his never-to-be-filmed epicSinbad in a Rented World– as a museum dedicated to Jack Smith and his work. This effort failed.

Until recently, Smith's archive was co-managed by Arcade, alongside the film historianJ. Hobermanvia their corporation, The Plaster Foundation, Inc. Within ten years of Smith's death, the Foundation, operating largely without funding but through donations and good will, was able to restore all of Smith's films, create a major retrospective curated byEdward Leffingwell[3]atPS 1,the Contemporary Arts Museum, now part ofMoMA,put his films back into international distribution, and publish several books on Jack Smith and his work.

In January 2004, theNew York Surrogate's Courtordered Hoberman and Arcade to return Smith's archive to his legal heir, estranged, surviving sister Sue Slater. Hoberman and Arcade fought to dismiss Slater's claim, arguing that she abandoned Jack's apartment and its contents; the Plaster Foundation created the archive and took possession of the work only after 14 years of repeated, documented attempts at communication with her. In a six-minute trial, Judge Eve Preminger rejected the Foundation's argument and awarded the archive to Slater.

By October 2006, the foundation still refused to surrender Smith's archive to the estate, claiming money owed them for expenses associated with managing the archive—and hoping Smith's work would be bought by an appropriate public institution that could safeguard his legacy and keep the works in the public eye. According to curator Jerry Tartaglia, the dispute was resolved as of 2008, with the purchase of Smith's estate by theGladstone Gallery.

Legacy

editSmith was one of the first proponents of theaestheticswhich came to be known as 'camp' and 'trash', usingno-budgetmeans of production (e.g. using discarded color reversal film stock) to create a visual cosmos heavily influenced by Hollywoodkitsch,orientalismand withFlaming Creaturescreated drag culture as it is currently known. Smith was heavily involved with John Vaccaro, founder of thePlayhouse of the Ridiculous,whose disregard for conventional theater practice deeply influenced Smith's ideas about performance art. In turn, Vaccaro was deeply influenced by Smith's aesthetics. It was Vaccaro who introduced Smith to glitter and in 1966 and 1967, Smith created costumes for Vaccaro's Playhouse of the Ridiculous. Smith's style influenced the film work ofAndy Warholas well as the early work ofJohn Waters.While Vaccaro and Smith disputed the idea that their sexual orientation was responsible for their art, all three are thought to have been part of the 1960s gay arts movement,[9]

In 1992, performerRon Vawterrecreated Smith's performance "What's Underground about Marshmallows" inRoy Cohn/Jack Smithwhich he presented in a live performance[10]and which was later released as a film directed by Jill Godmilow and produced byJonathan Demme.[11]

PlaywrightRichard Foremanwas influenced by Smith.[12]

Tony Conradproduced two CDs from the Jack Smith tape archives subtitled56 Ludlow Streetthat were recorded at 56Ludlow Streetbetween 1962 and 1964.[13]

In 2017, Jerry Tartaglia directed a documentary calledEscape from Rented Island: The Lost Paradise of Jack Smithwhich is a film essay concerning the works of Jack Smith, aimed at the artist's most devoted followers.[14]

In 2009, Germany'sArsenal Institute for Film and Video Artin Berlin staged Five Flaming Days in a Rented World, a festival and conference on Smith's work.[15]The event included several commissioned short films in tribute to Smith's films, the most noted of which wasGuy Maddin'sThe Little White Cloud That Cried.[15]

Selected filmography

edit- By Jack Smith

- 1952:Buzzards Over Baghdad[3]

- 1961:Scotch Tape

- 1963:Flaming Creatures(b/w, 46 minutes)

- 1963:Normal Love(120 minutes)

- 1967:No President(a/k/aThe Kidnapping of Wendell Willkie by The Love Bandit,ca. minutes)

- With Jack Smith as actor

- 1960: inKen Jacobs'sLittle Stabs at Happiness[3]

- 1963: in Jacobs'sBlonde Cobra[16]

- 1963: inRon Rice'sQueen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man[3]

- 1963: in Rice'sChumlum[3]

- 1965: inAndy Warhol'sCamp

- 1966: in Warhol'sHedy(a/k/aHedy the Shoplifter) starringMario MontezandMary Woronov

- 1971: inJohn LennonandYoko Ono'sUp Your Legs Forever[17]

- 1974: in Ted Gershunny'sSilent Night, Bloody NightstarringMary Woronov,Patrick O'Neal,John Carradine,Candy Darling,Ondine,andTally Brown

- 1989: in Ari Roussimoff (Frankenhooker)'sShadows in the City[3]

- About Jack Smith

- 2006:Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis,documentary written, directed, and co-produced byMary Jordan[3]

Books by Smith

edit- 196016 Immortal Photos

- 1962The Beautiful Book(dead language press, republished 2001 Granary Books)

References

edit- ^[1]Jack Smith 1932–1989 at Visual Aids

- ^"Forever Flaming: Jack Smith at MoMA".The L Magazine.22 November 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 2018-07-30.Retrieved2018-10-18.

- ^abcdefgh"Film Examines Art-World Provocateur"Archived2007-06-28 at theWayback MachineBy David Ebony,Art in America,May '07, p.47. Retrieved 2-3-09. Includes photos of Smith in pre-production forFlaming Creaturesand inShadows in the City.

- ^Penny, Arcade."The Last Days and Moments of Jack Smith".Retrieved17 September2013.

- ^Watson, Steven(2003), "Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties," Pantheon Books, pp. 51-54.

- ^Mark Bloch,"Jack Smith: Art Crust of Spiritual Oasis,"The Brooklyn Rail,July 2018.

- ^Sylvère Lotringer& David Morris (Eds),Schizo-Culture: The Event, The Book,MIT Press,2013, pp. 192–203.

- ^"Honorary Degrees | Whittier College".www.whittier.edu.Retrieved2020-02-20.

- ^Jones, Sonya L. (1998),Gay and Lesbian Literature Since World War II: History and Memory,Haworth Press, p. 18,ISBN0-7890-0349-X

- ^Holden, Stephen (1992-05-03),"Two Strangers Meet Through an Actor",New York Times

- ^Holden, Stephen (1995-08-04),"2 Extremes of Gay Life",New York Times

- ^Als, Hilton(2009-11-16),"Talk Talk: Richard Foreman puts language onstage",The New Yorker

- ^Jack Smith - Les Evening Gowns Damnees - 56 Ludlow Street 1962–1964, Volume IandJack Smith - Silent Shadows On Cinemaroc Island - 56 Ludlow Street 1962-1964 Volume II,CDs released on Table of the Elements in 1997.

- ^DeFore, John (26 April 2017)."'Escape From Rented Island: The Lost Paradise of Jack Smith': Film Review ".The Hollywood Reporter.Retrieved10 September2019.

- ^abAndrea Grover,"Jack Smith and Kenneth Anger’s Love Child".Glasstire,April 27, 2010.

- ^"Electronic Arts Intermix: Blonde Cobra, Ken Jacobs".www.eai.org.Retrieved2022-08-29.

- ^Jonathan Cott (16 July 2013).Days That I'll Remember: Spending Time with John Lennon & Yoko Ono.Omnibus Press. p. 74.ISBN978-1-78323-048-8.

Further reading

edit- J. Hoberman,On Jack Smith's 'Flaming Creatures' (And Other Secret-Flix of Cinemaroc),New York: Granary Books, 2001.

- J. Hoberman and Edward Leffingwell (eds.),Wait for Me at the Bottom of the Pool: The Writings of Jack Smith,London and New York: High Risk Books and PS1, 1997.

- Dominic Johnson.Glorious Catastrophe: Jack Smith, Performance and Visual Culture,Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2012.

- Edward Leffingwell (Edward and Carole Kismaric, andMarvin Heiferman,eds.)Flaming Creature: Jack Smith, His Amazing Life and Times,London: Serpent's Tail, 1997.

- D. Reisman. "In the Grip of the Lobster: Jack Smith Remembered",Millennium Film Journal23/24, Winter 1990-91.

External links

edit- Biography at WarholStars.com

- Jack Smith(I)atIMDb

- Jack Smith Papers,Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University Special Collections