Jiu Ge,orNine Songs,(Chinese:Cửu ca;pinyin:Jiǔ Gē;lit.'Nine Songs') is an ancient set of poems. Together, these poems constitute one of the 17 sections of the poetry anthology which was published under the title of theChuci(also known as theSongs of Chuor as theSongs of the South). Despite the "Nine ",in the title, the number of these poetic pieces actually consists of eleven separate songs, or elegies.[1]This set of verses seems to be part of some rituals of theYangzi Rivervalley area (as well as a northern tradition or traditions) involving the invocation of divine beings and seeking their blessings by means of a process of courtship.[2]Though the poetry consists of lyrics written for a performance, the lack of indications of who is supposed to be singing at any one time or whether some of the lines represent lines for a chorus makes an accurate reconstruction impossible. Nonetheless there are internal textual clues, for example indicating the use of costumes for the performers, and an extensive orchestra.[3]

Authorship and dating

editIn common with otherChuciworks, the authorship of these 11 poems has been attributed to the poetQu Yuan,who lived over two-thousand years ago. Sinologist David Hawkesfinds evidence for this eclectic suite of eleven poems having been written by "a poet (or poets) at the Chu court inShou-chun(241–223) B.C. "[4]

Text

editThe"Jiu Ge"songs include eleven (despite the "Nine" in the title). Nine of the verses are addressed to deities by a type ofshaman,one to the spirits of fallen warriors who died fighting far from home, and the concluding verse.[5]The reason for the discrepancy between the 9 verses referred to in the title and the fact that there are actually 11 is uncertain, although an important question, which has had several possible explanations put forth. Of these explanations, some may be rooted in general Chinese number magic or symbology. More specifically, David Hawkes points out that "nine songs" is referenced in the seminalChu Ciwork,Li Sao,referring to the nine (twice times nine?) dances ofQi of Xia.[6]

Why nine?

editCritics and scholars have elaborated various hypotheses as to why theJiu Ge( "Nine Songs") consists of eleven songs, rather than nine. An obvious, and common, suggestion has been that Number 1 and Number 11 songs are somehow to be classified as an introduction and aluan:examination of Song 1 and Song 11 fails to support this convenient conjecture, however.[7]SinologistsMasaru AokiandDavid Hawkespropose that for performance purposes there were nine songs/dances performed at each a spring and at an autumn performance, with the spring performance featuring Songs 3 and 5, but not 4 or 6, and the autumnal performance 4 and 6, but not 3 or 5 (with the songs otherwise being performed in numerical order).[8]Another explanation has to do with ancient ideas about numbers and numbering, where by the use of a numeric term, an order of magnitude, estimation, or other symbolic qualities are meant, rather than a specific quantity.[9]11 songs could be "about 9" songs.

List of contents

editThe following table shows the eleven individual poems of theNine Songs.The English translations are following those of David Hawkes,[10]although he usesRoman numeralsfor the traditional song order.

| Standard order | English translation | Transcription (based on Pinyin) | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Great Unity, God of the Eastern Sky | "Dong Huang Tai Yi" | Đông hoàng thái nhất | Đông hoàng thái nhất |

| 2 | The Lord within the Clouds | "Yun Zhong Jun" | Vân trung quân | Vân trung quân |

| 3 | The God of the Xiang | "Xiang Jun" | Tương quân | Tương quân |

| 4 | The Lady of the Xiang | "Xiang Fu Ren" | Tương phu nhân | Tương phu nhân |

| 5 | The Greater Master of Fate | "Da Si Ming" | Đại tư mệnh | Đại tư mệnh |

| 6 | The Lesser Master of Fate | "Shao Si Ming" | Thiếu tư mệnh | Thiếu tư mệnh |

| 7 | The Lord of the East | "Dong Jun" | Đông quân | Đông quân |

| 8 | The River Earl | "He Bo" | Hà bá | Hà bá |

| 9 | The Mountain Spirit | "Shan Gui" | Sơn quỷ | Sơn quỷ |

| 10 | Hymn to the Fallen | "Guo Shang" | Quốc thương | Quốc thương |

| 11 | Honouring the Dead | "Li Hun" | Lễ hồn | Lễ hồn |

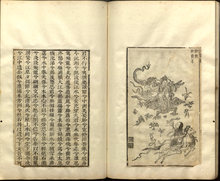

Illustrated versions

editIllustrated versions of theChuciexist. Below is a selection from the "Nine Songs":

Divine beings

editOf the 11 songs of the "Jiu Ge", 9 are addressed to deities and 1 to the spirits of dead heroes (the last verse section is a conclusional cauda).[11]These deities includeHe Bo,also known as the River Earl or as the Count of the River, and the Lord (or God) of the Clouds.

Donghuang Taiyi

edit.

The character with which Song 1 concerns itself isDonghuang Taiyi,combining the termsTaiyiandDonghuang.This is not a common concept in previous Chinese historical sources. The character of this divinity resolves readily as two familiar parts, here coupled together.

God of Clouds

editThe God of Clouds (Yunzhong Jun) was worshipped in the hope of rain and good weather for crops. This poem can be divided into two parts: one part is sung by the person who does the offering and the other part is sung by the person who acts as the God of Clouds in the form of antiphonal singing in order to show their admiration towards her. This poem expresses the characteristics of the God of Clouds, the deep desire that human have towards God, and how God responds to people's prayer through the antiphonal singing of human and God.

He Bo, the Earl of Yellow River

editThe Earl ofYellow River(one of the world's major rivers, and one with close association with Chinese Culture) has been associated with control of that wild river's occasional devastating floods and general qualities as an agricultural aquifer.

Lord of the East

editThe Lord of the East is the sun, in his aspect as a deity of the morning.

Master of Fate

editThe Master of Fate is known asSiming( tư mệnh ) with various English translations (such as, Controller of Fate, Deified Judge of Life, and Director of Destinies). Siming is both an abstract deity (or more rather title thereof) and a celestialasterism.In the Daoist case of theThree Worms,Siming, as Director of Destinies, has the bureaucratic function of human lifespan allocation. As an asterism, or apparent stellar constellation, Siming is associated both with theWenchang Wangstar pattern, near theBig Dipper,in (Aquarius (Chinese astronomy)), and with a supposed celestial bureaucrat official of fate.

The astronomicalSiming(actually part of asterism hư, "Emptiness" ) consists of the Deified Judge of Life star group. Sīmìngyī: (24 Aquarii,Tư mệnh nhất ) and Sīmìngèr (26 Aquarii,Tư mệnh nhị ).

The earthly Siming has the bureaucratic function of human lifespan allocation.

Qu Yuan

editQu Yuan is the protagonist and author of much of theChu ciopus: whether or not he wrote theJiu gepieces while he was in exile is an open question. Certainly the work appears underlain by earlier tradition, as well as possible editing during the reign ofHan Wudi.Whether he makes a cameo appearance is also not known.

Shaman

editThe shamanic voice is an important part of the proceedings here.

Shan Gui, the Mountain Spirit

editShan Gui(SơnQuỷ), literally "Mountain Spirit" is here actually a goddess who is "lovesick" and pining for her lord.[12]See (§Mountain Spiritbelow).

Spirits of the Fallen and the Dead

editPresupposing some sort of continuation of life after death: ghosts or spirits.

Taiyi

editTaiyi also known as: Tai Yi, Great Unity, and so on, is a familiar deity from the Chinese Daoist/shamanic tradition.

Xiang River Deities

editThe deities of theXiangwaters, are theXiangshuishen.Various conceptions of them exist. Of these conceptions, one set consists of ancient folk belief, and another of more modern interpretation.

Individual poems

editThe individual poems of theJiu Geare related to each other as parts of a religious drama, meant for performance; however, the individual roles of each and their relationship to each other is a matter for interpretive reinterpretation, rather than something known.[13]

Some aspects of the dramatic performance are known, mostly through internal evidence. The performances were evidently replete with fantastic shamanic costumes, were probably performed indoors, and with orchestral accompaniment to the tune of "lithophones, musical bells, drums, and various kinds of wind and string instruments."[14]

However, in the case of any individual poem, its role in the overall performance is not necessarily determinable. They may represent monologues, dialogues, choral pieces, or combinations thereof, within the individual pieces or between them.[15]

The titles of the individual poems which follow are loosely based on David Hawkes:

East Emperor/Grand Unity

editThe firstJiu gepoetic piece is a dedication to a deity ( "Dong huang tai yi" ).

Lord in the Clouds

editThe secondJiu gepoetic piece addresses another deity ( "Yun-zhong jun" ).

Xiang deity(two titles)

editThe third and fourthJiu gepoetic pieces involve a deity, male, female, singular or plural: the Chinese is not marked for number or gender ( "Xiang jun" and "Xiang fu-ren" ).

Master of Fate(two titles)

editThe fifth and sixthJiu gepoetic pieces involve a deity singular or plural: the Chinese is not clear as to whether the "lesser" and "greater" in the titles refers to a distinction between the two Siming (Master of Fate) poems or if it refers to a distinction between two Siming, Masters of Fate ( "Xiang jun" and "Xiang fu-ren" ).

East Lord

editThe seventhJiu gepoetic piece addresses involves the deity "Dong jun".

River Earl

editThe eighthJiu gepoetic piece involves another deity ( "Hebo" ).

Mountain Spirit

editThe ninthJiu gepoetic piece addresses theShan guiwhich is literally "Mountain Spirit", but here she is rather a Mountain Goddess, wearing clothing ofclimbing-fig vine[a]and a girdle ofdodder(or hanging moss).[b]She is possibly to be identified with the Wushan Mountain goddess,Yaoji,and this "lovesick fairy queen" of the mount is presumably "waiting forKing Xiang of Chu".[19][20]She is depicted as "riding a red leopard and holding awen li(patterned wildcat,Văn li) ",[21][22]or perhaps rather riding a fragrant car[c]drawn by these "leopards".[23]

Hymn to the Fallen

editThe tenthJiu gepoem (Guo shang) is a hymn to soldiers killed in war ( "Guo shang" ).Guó( quốc ) means the "state", "kingdom", or "nation".Shāng( thương ) means to "die young". Put together, the title refers to those who meet death in the course of fighting for their country. David Hawkes describes it as "surely one of the most beautiful laments for fallen soldiers in any language".[24]The meter is a regular seven-character verse, with three characters separated by the exclamatory particle "Hề" followed by three more characters, each composing a half line, for a total of nine lines of 126 characters.

Background

editThe historical background of the poem involves the ancient type of warfare practiced in ancient China. Included are references to arms and weapons, ancient states or areas, and the mixed use of chariots in warfare. A good historical example of this type of contest is the "Battle of Yanling",which features similar characteristics and problems experienced by participants in this type of fighting, such as greatly elevated mortality rates for both horses and humans.

Poem

editThe poem is translated as "Battle" byArthur Waley(1918, inA Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems[25])

BATTLE

....

“We grasp our battle-spears: we don our breast-plates of hide.

The axles of our chariots touch: our short swords meet.

Standards obscure the sun: the foe roll up like clouds.

Arrows fall thick: the warriors press forward.

They menace our ranks: they break our line.

The left-hand trace-horse is dead: the one on the right is smitten.

The fallen horses block our wheels: they impede the yoke-horses!”

They grasp their jade drum-sticks: they beat the sounding drums.

Heaven decrees their fall: the dread Powers are angry.

The warriors are all dead: they lie on the moor-field.

They issued but shall not enter: they went but shall not return.

The plains are flat and wide: the way home is long.

Their swords lie beside them: their black bows, in their hand.

Though their limbs were torn, their hearts could not be repressed.

They were more than brave: they were inspired with the spirit of

“Wu.”

Steadfast to the end, they could not be daunted.

Their bodies were stricken, but their souls have taken Immortality–

Captains among the ghosts, heroes among the dead.

I.e., military genius.

Honoring the Dead

editThe eleventhJiu gepoetic piece concludes the corpus ( "Li hun" ).

Translations

editThe first translation of theNine Songsinto a European language was done by the Viennese scholarAugust Pfizmaier(1808–1887).[26]Over 100 years laterArthur Waley(1889–1966) accredited it as "an extremely good piece of work, if one considers the time when it was made and the meagreness of the material to which Pfizmaier had access."[27]

See also

edit- Chariots in ancient China

- Taiyi

- Chu ci

- Chu (state)

- Jiu Zhang

- He Bo

- List of Chuci contents

- Liu An

- Liu Xiang (scholar)

- Qin (state)

- Qu Yuan

- Rhinoceroses in ancient China

- Xiao (mythology)

- Simians (Chinese poetry)

- Song Yu

- Wang Yi (librarian)

- Wu ( võ )at Wiktionary

- Wu (state)

- Xiang River goddesses

- Xiao (mythology)

- Yunzhongzi

Explanatory notes

editReferences

edit- Citations

- ^Murck, 11

- ^Davis, xlvii

- ^Hawkes, 95-96

- ^Hawkes, 98

- ^Hawkes, 95

- ^Hawkes, 97

- ^Hawkes, 99

- ^Hawkes, 99-100

- ^Hawkes, 101

- ^Hawkes, 101-118

- ^Hawkes, 95

- ^Yang ed. & Xu tr. (1996),pp. 48–49.

- ^Hawkes, 95-96

- ^Hawkes, 96

- ^Hawkes, 96 andpassim

- ^Li Shizhen(2022)."Herbs VII. 18-01 Tus si ziCuscuta chinensisLam. Dodder "Thố ti tử.Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume V: Creeping Herbs, Water Herbs, Herbs Growing on Stones, Mosses, Cereals.Translated by Paul U. Unschuld. Univ of California Press. pp. 35–36.ISBN9780520385054.,citingMao Commentaryfor equatingtusiwithnüluo

- ^Liu, J. C. (1927–1928)."Remarks on the Mistletoe (Viscum) ".Bulletin of the Peking Society of Natural History.II, part 4: 535.

- ^Legge, James,ed. (1871).The Chinese Classics: With a Translation, Critical and Exegetical Notes, Prolegomena, and Copious Indexes.London: Trübner & Co. pp. 389–380, note.

- ^Yang ed. & Xu tr. (1996),pp. 18–, 48–49

- ^Ma, Boying (2020).History Of Medicine In Chinese Culture, A (In 2 Volumes)Trung quốc y học văn hóa sử.World Scientific. p. 74.ISBN9789813238008.

- ^Which commentators equate with a "divine leopard catThầnLi",i.e., civet cat.

- ^Li Shizhen(2021)."Four-legged Animals II. 51-21 Ling mao Civet cat.Viverra zibethaL. "Linh miêu.Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume IX: Fowls, Domestic and Wild Animals, Human Substances.Translated by Paul U. Unschuld. Univ of California Press. pp. 795–796.ISBN9780520379923.

- ^Yang ed. & Xu tr. (1996),p. 49.

- ^Hawkes, 116-117

- ^ http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/42290

- ^Waley, 15: August Pfizmaier: Das Li-sao und die Neun Gesdnge. In Denkschriften der Phil. Hist. Classe der Kaiserl. Akad. d. Wissen- schaften, Vienna, 1852.

- ^Ibid., 18

- Bibliography

- Davis, A. R. (Albert Richard), Editor and Introduction,(1970),The Penguin Book of Chinese Verse.(Baltimore: Penguin Books).

- Hawkes, David,translator and introduction (2011 [1985]). Qu Yuanet al.,The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets.London: Penguin Books.ISBN978-0-14-044375-2

- Murck, Alfreda (2000).Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent.Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute.ISBN0-674-00782-4.

- Waley, Arthur, tr. 1955.The Nine Songs.Allen and Unwin.[1]

- Yang Fengbin, ed. (1996).Poetry of the South (Chinese-English Parallel) Zhu zi( hán anh đối chiếu ) sở từ.Translated by Xu Yuanchong. Hunan chu ban she.