Incelestial mechanics,aKepler orbit(orKeplerian orbit,named after the German astronomerJohannes Kepler) is the motion of one body relative to another, as anellipse,parabola,orhyperbola,which forms a two-dimensionalorbital planein three-dimensional space. A Kepler orbit can also form astraight line.It considers only the point-like gravitational attraction of two bodies, neglectingperturbationsdue to gravitational interactions with other objects,atmospheric drag,solar radiation pressure,a non-sphericalcentral body, and so on. It is thus said to be a solution of a special case of thetwo-body problem,known as theKepler problem.As a theory inclassical mechanics,it also does not take into account the effects ofgeneral relativity.Keplerian orbits can beparametrizedinto sixorbital elementsin various ways.

In most applications, there is a large central body, the center of mass of which is assumed to be the center of mass of the entire system. By decomposition, the orbits of two objects of similar mass can be described as Kepler orbits around their common center of mass, theirbarycenter.

Introduction

editFrom ancient times until the 16th and 17th centuries, the motions of the planets were believed to follow perfectly circulargeocentricpaths as taught by the ancient Greek philosophersAristotleandPtolemy.Variations in the motions of the planets were explained by smaller circular paths overlaid on the larger path (seeepicycle). As measurements of the planets became increasingly accurate, revisions to the theory were proposed. In 1543,Nicolaus Copernicuspublished aheliocentricmodel of theSolar System,although he still believed that the planets traveled in perfectly circular paths centered on the Sun.[1]

Development of the laws

editIn 1601,Johannes Kepleracquired the extensive, meticulous observations of the planets made byTycho Brahe.Kepler would spend the next five years trying to fit the observations of the planetMarsto various curves. In 1609, Kepler published the first two of his threelaws of planetary motion.The first law states:

More generally, the path of an object undergoing Keplerian motion may also follow aparabolaor ahyperbola,which, along with ellipses, belong to a group of curves known asconic sections.Mathematically, the distance between a central body and an orbiting body can be expressed as:

where:

- is the distance

- is thesemi-major axis,which defines the size of the orbit

- is theeccentricity,which defines the shape of the orbit

- is thetrue anomaly,which is the angle between the current position of the orbiting object and the location in the orbit at which it is closest to the central body (called theperiapsis).

Alternately, the equation can be expressed as:

Whereis called thesemi-latus rectumof the curve. This form of the equation is particularly useful when dealing with parabolic trajectories, for which the semi-major axis is infinite.

Despite developing these laws from observations, Kepler was never able to develop a theory to explain these motions.[2]

Isaac Newton

editBetween 1665 and 1666,Isaac Newtondeveloped several concepts related to motion, gravitation and differential calculus. However, these concepts were not published until 1687 in thePrincipia,in which he outlined hislaws of motionand hislaw of universal gravitation.His second of his three laws of motion states:

Theaccelerationof a body is parallel and directly proportional to the netforceacting on the body, is in the direction of the net force, and is inversely proportional to themassof the body:

Where:

- is the force vector

- is the mass of the body on which the force is acting

- is the acceleration vector, the second time derivative of the position vector

Strictly speaking, this form of the equation only applies to an object of constant mass, which holds true based on the simplifying assumptions made below.

Newton's law of gravitation states:

Everypoint massattracts every other point mass by aforcepointing along the line intersecting both points. The force isproportionalto the product of the two masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the point masses:

where:

- is the magnitude of the gravitational force between the two point masses

- is thegravitational constant

- is the mass of the first point mass

- is the mass of the second point mass

- is the distance between the two point masses

From the laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation, Newton was able to derive Kepler's laws, which are specific to orbital motion in astronomy. Since Kepler's laws were well-supported by observation data, this consistency provided strong support of the validity of Newton's generalized theory, and unified celestial and ordinary mechanics. These laws of motion formed the basis of moderncelestial mechanicsuntilAlbert Einsteinintroduced the concepts ofspecialandgeneralrelativity in the early 20th century. For most applications, Keplerian motion approximates the motions of planets and satellites to relatively high degrees of accuracy and is used extensively inastronomyandastrodynamics.

Simplified two body problem

editTo solve for the motion of an object in atwo body system,two simplifying assumptions can be made:

- The bodies are spherically symmetric and can be treated as point masses.

- There are no external or internal forces acting upon the bodies other than their mutual gravitation.

The shapes of large celestial bodies are close to spheres. By symmetry, the net gravitational force attracting a mass point towards a homogeneous sphere must be directed towards its centre. Theshell theorem(also proven by Isaac Newton) states that the magnitude of this force is the same as if all mass was concentrated in the middle of the sphere, even if the density of the sphere varies with depth (as it does for most celestial bodies). From this immediately follows that the attraction between two homogeneous spheres is as if both had its mass concentrated to its center.

Smaller objects, likeasteroidsorspacecraftoften have a shape strongly deviating from a sphere. But the gravitational forces produced by these irregularities are generally small compared to the gravity of the central body. The difference between an irregular shape and a perfect sphere also diminishes with distances, and most orbital distances are very large when compared with the diameter of a small orbiting body. Thus for some applications, shape irregularity can be neglected without significant impact on accuracy. This effect is quite noticeable for artificial Earth satellites, especially those in low orbits.

Planets rotate at varying rates and thus may take a slightly oblate shape because of the centrifugal force. With such an oblate shape, the gravitational attraction will deviate somewhat from that of a homogeneous sphere. At larger distances the effect of this oblateness becomes negligible. Planetary motions in the Solar System can be computed with sufficient precision if they are treated as point masses.

Two point mass objects with massesandand position vectorsandrelative to someinertial reference frameexperience gravitational forces:

whereis the relative position vector of mass 1 with respect to mass 2, expressed as:

andis theunit vectorin that direction andis thelengthof that vector.

Dividing by their respective masses and subtracting the second equation from the first yields the equation of motion for the acceleration of the first object with respect to the second:

| 1 |

whereis the gravitational parameter and is equal to

In many applications, a third simplifying assumption can be made:

- When compared to the central body, the mass of the orbiting body is insignificant. Mathematically,m1>>m2,soα=G(m1+m2) ≈Gm1.Suchstandard gravitational parameters,often denoted as,are widely available for Sun, major planets and Moon, which have much larger massesthan their orbiting satellites.

This assumption is not necessary to solve the simplified two body problem, but it simplifies calculations, particularly with Earth-orbiting satellites and planets orbiting the Sun. EvenJupiter's mass is less than the Sun's by a factor of 1047,[3]which would constitute an error of 0.096% in the value of α. Notable exceptions include the Earth-Moon system (mass ratio of 81.3), the Pluto-Charon system (mass ratio of 8.9) and binary star systems.

Under these assumptions the differential equation for the two body case can be completely solved mathematically and the resulting orbit which follows Kepler's laws of planetary motion is called a "Kepler orbit". The orbits of all planets are to high accuracy Kepler orbits around the Sun. The small deviations are due to the much weaker gravitational attractions between the planets, and in the case ofMercury,due togeneral relativity.The orbits of the artificial satellites around the Earth are, with a fair approximation, Kepler orbits with small perturbations due to the gravitational attraction of the Sun, the Moon and the oblateness of the Earth. In high accuracy applications for which the equation of motion must be integrated numerically with all gravitational and non-gravitational forces (such assolar radiation pressureandatmospheric drag) being taken into account, the Kepler orbit concepts are of paramount importance and heavily used.

Keplerian elements

editAny Keplerian trajectory can be defined by six parameters. The motion of an object moving in three-dimensional space is characterized by a position vector and a velocity vector. Each vector has three components, so the total number of values needed to define a trajectory through space is six. An orbit is generally defined by six elements (known asKeplerian elements) that can be computed from position and velocity, three of which have already been discussed. These elements are convenient in that of the six, five are unchanging for an unperturbed orbit (a stark contrast to two constantly changing vectors). The future location of an object within its orbit can be predicted and its new position and velocity can be easily obtained from the orbital elements.

Two define the size and shape of the trajectory:

Three define the orientation of theorbital plane:

- Inclination() defines the angle between the orbital plane and the reference plane.

- Longitude of the ascending node() defines the angle between the reference direction and the upward crossing of the orbit on the reference plane (the ascending node).

- Argument of periapsis() defines the angle between the ascending node and the periapsis.

And finally:

- True anomaly() defines the position of the orbiting body along the trajectory, measured from periapsis. Several alternate values can be used instead of true anomaly, the most common beingthemean anomalyand,the time since periapsis.

Because,andare simply angular measurements defining the orientation of the trajectory in the reference frame, they are not strictly necessary when discussing the motion of the object within the orbital plane. They have been mentioned here for completeness, but are not required for the proofs below.

For movement under any central force, i.e. a force parallel tor,thespecific relative angular momentumstays constant:

Since the cross product of the position vector and its velocity stays constant, they must lie in the same plane, orthogonal to.This implies the vector function is aplane curve.

Because the equation has symmetry around its origin, it is easier to solve in polar coordinates. However, it is important to note that equation (1) refers to linear accelerationas opposed to angularor radialacceleration. Therefore, one must be cautious when transforming the equation. Introducing a cartesian coordinate systemandpolar unit vectorsin the plane orthogonal to:

We can now rewrite the vector functionand its derivatives as:

(see "Vector calculus"). Substituting these into (1), we find:

This gives the ordinary differential equation in the two variablesand:

| 2 |

In order to solve this equation, all time derivatives must be eliminated. This brings:

| 3 |

Taking the time derivative of (3) gets

| 4 |

Equations (3) and (4) allow us to eliminate the time derivatives of.In order to eliminate the time derivatives of,the chain rule is used to find appropriate substitutions:

| 5 |

| 6 |

Using these four substitutions, all time derivatives in (2) can be eliminated, yielding anordinary differential equationforas function of

| 7 |

The differential equation (7) can be solved analytically by the variable substitution

| 8 |

Using the chain rule for differentiation gets:

| 9 |

| 10 |

Using the expressions (10) and (9) forandgets

| 11 |

with the general solution

| 12 |

whereeandare constants of integration depending on the initial values forsand

Instead of using the constant of integrationexplicitly one introduces the convention that the unit vectorsdefining the coordinate system in the orbital plane are selected such thattakes the value zero andeis positive. This then means thatis zero at the point whereis maximal and thereforeis minimal. Defining the parameterpasone has that

Alternate derivation

editAnother way to solve this equation without the use of polar differential equations is as follows:

Define a unit vector,,such thatand.It follows that

Now consider

(seeVector triple product). Notice that

Substituting these values into the previous equation gives:

Integrating both sides:

wherecis a constant vector. Dotting this withryields an interesting result: whereis the angle betweenand.Solving forr :

Notice thatare effectively the polar coordinates of the vector function. Making the substitutionsand,we again arrive at the equation

| 13 |

This is the equation in polar coordinates for aconic sectionwith origin in a focal point. The argumentis called "true anomaly".

Eccentricity Vector

editNotice also that, sinceis the angle between the position vectorand the integration constant,the vectormust be pointing in the direction of theperiapsisof the orbit. We can then define theeccentricity vectorassociated with the orbit as:

whereis the constant angular momentum vector of the orbit, andis the velocity vector associated with the position vector.

Obviously, theeccentricity vector,having the same direction as the integration constant,also points to the direction of theperiapsisof the orbit, and it has the magnitude of orbital eccentricity. This makes it very useful inorbit determination(OD) for theorbital elementsof an orbit when astate vector[] or [] is known.

Properties of trajectory equation

editForthis is a circle with radiusp.

Forthis is anellipsewith

| 14 |

| 15 |

Forthis is aparabolawith focal length

Forthis is ahyperbolawith

| 16 |

| 17 |

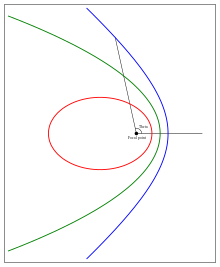

The following image illustrates a circle (grey), an ellipse (red), a parabola (green) and a hyperbola (blue)

The point on the horizontal line going out to the right from the focal point is the point withfor which the distance to the focus takes the minimal valuethe pericentre. For the ellipse there is also an apocentre for which the distance to the focus takes the maximal valueFor the hyperbola the range foris and for a parabola the range is

Using the chain rule for differentiation (5), the equation (2) and the definition ofpasone gets that the radial velocity component is

| 18 |

and that the tangential component (velocity component perpendicular to) is

| 19 |

The connection between the polar argumentand timetis slightly different for elliptic and hyperbolic orbits.

For an elliptic orbit one switches to the "eccentric anomaly"Efor which

| 20 |

| 21 |

and consequently

| 22 |

| 23 |

and the angular momentumHis

| 24 |

Integrating with respect to timetgives

| 25 |

under the assumption that timeis selected such that the integration constant is zero.

As by definition ofpone has

| 26 |

this can be written

| 27 |

For a hyperbolic orbit one uses thehyperbolic functionsfor the parameterisation

| 28 |

| 29 |

for which one has

| 30 |

| 31 |

and the angular momentumHis

| 32 |

Integrating with respect to timetgets

| 33 |

i.e.

| 34 |

To find what time t that corresponds to a certain true anomalyone computes corresponding parameterEconnected to time with relation (27) for an elliptic and with relation (34) for a hyperbolic orbit.

Note that the relations (27) and (34) define a mapping between the ranges

Some additional formulae

editFor anelliptic orbitone gets from (20) and (21) that

| 35 |

and therefore that

| 36 |

From (36) then follows that

From the geometrical construction defining theeccentric anomalyit is clear that the vectorsandare on the same side of thex-axis. From this then follows that the vectorsandare in the same quadrant. One therefore has that

| 37 |

and that

| 38 |

| 39 |

where ""is the polar argument of the vectorandnis selected such that

For the numerical computation ofthe standard functionATAN2(y,x)(or indouble precisionDATAN2(y,x)) available in for example the programming languageFORTRANcan be used.

Note that this is a mapping between the ranges

For ahyperbolic orbitone gets from (28) and (29) that

| 40 |

and therefore that

| 41 |

As and asandhave the same sign it follows that

| 42 |

This relation is convenient for passing between "true anomaly" and the parameterE,the latter being connected to time through relation (34). Note that this is a mapping between the ranges and thatcan be computed using the relation

From relation (27) follows that the orbital periodPfor an elliptic orbit is

| 43 |

As the potential energy corresponding to the force field of relation (1) is it follows from (13), (14), (18) and (19) that the sum of the kinetic and the potential energy for an elliptic orbit is

| 44 |

and from (13), (16), (18) and (19) that the sum of the kinetic and the potential energy for a hyperbolic orbit is

| 45 |

Relative the inertial coordinate system in the orbital plane withtowards pericentre one gets from (18) and (19) that the velocity components are

| 46 |

| 47 |

The equation of the center relates mean anomaly to true anomaly for elliptical orbits, for small numerical eccentricity.

Determination of the Kepler orbit that corresponds to a given initial state

editThis is the "initial value problem"for the differential equation (1) which is a first order equation for the 6-dimensional "state vector"when written as

| 48 |

| 49 |

For any values for the initial "state vector"the Kepler orbit corresponding to the solution of this initial value problem can be found with the following algorithm:

Define the orthogonal unit vectorsthrough

| 50 |

| 51 |

withand

From (13), (18) and (19) follows that by setting

| 52 |

and by definingandsuch that

| 53 |

| 54 |

where

| 55 |

one gets a Kepler orbit that for true anomalyhas the samer,andvalues as those defined by (50) and (51).

If this Kepler orbit then also has the samevectors for this true anomalyas the ones defined by (50) and (51) the state vectorof the Kepler orbit takes the desired valuesfor true anomaly.

The standard inertially fixed coordinate systemin the orbital plane (withdirected from the centre of the homogeneous sphere to the pericentre) defining the orientation of the conical section (ellipse, parabola or hyperbola) can then be determined with the relation

| 56 |

| 57 |

Note that the relations (53) and (54) has a singularity whenand i.e.

| 58 |

which is the case that it is a circular orbit that is fitting the initial state

The osculating Kepler orbit

editFor any state vectorthe Kepler orbit corresponding to this state can be computed with the algorithm defined above. First the parametersare determined fromand then the orthogonal unit vectors in the orbital planeusing the relations (56) and (57).

If now the equation of motion is

| 59 |

where is a function other than the resulting parameters,,,,defined bywill all vary with time as opposed to the case of a Kepler orbit for which only the parameterwill vary.

The Kepler orbit computed in this way having the same "state vector" as the solution to the "equation of motion" (59) at timetis said to be "osculating" at this time.

This concept is for example useful in case where

is a small "perturbing force" due to for example a faint gravitational pull from other celestial bodies. The parameters of the osculating Kepler orbit will then only slowly change and the osculating Kepler orbit is a good approximation to the real orbit for a considerable time period before and after the time of osculation.

This concept can also be useful for a rocket during powered flight as it then tells which Kepler orbit the rocket would continue in case the thrust is switched off.

For a "close to circular" orbit the concept "eccentricity vector"defined asis useful. From (53), (54) and (56) follows that

| 60 |

i.e.is a smooth differentiable function of the state vectoralso if this state corresponds to a circular orbit.

See also

editCitations

edit- ^Copernicus. pp 513–514

- ^Bate, Mueller, White. pp 177–181

- ^"NASA website".Archived fromthe originalon 16 February 2011.Retrieved12 August2012.

References

edit- El'Yasberg "Theory of flight of artificial earth satellites", Israel program for Scientific Translations (1967)

- Bate, Roger; Mueller, Donald; White, Jerry (1971).Fundamentals of Astrodynamics.Dover Publications, Inc., New York.ISBN0-486-60061-0.

- Copernicus, Nicolaus(1952), "Book I, Chapter 4, The Movement of the Celestial Bodies Is Regular, Circular, and Everlasting-Or Else Compounded of Circular Movements",On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres,Great Books of the Western World, vol. 16, translated by Charles Glenn Wallis, Chicago: William Benton, pp.497–838

External links

edit- JAVA applet animating the orbit of a satellitein an elliptic Kepler orbit around the Earth with any value for semi-major axis and eccentricity.