Norfolk Island(/ˈnɔːrfək/NOR-fək,locally/ˈnɔːrfoʊk/NOR-fohk;[9]Norfuk:Norf'k Ailen[10]) is anexternal territoryofAustralialocated in the Pacific Ocean betweenNew ZealandandNew Caledonia,approximately 1,412 kilometres (877 mi) east of Australia'sEvans Headand about 900 kilometres (560 mi) fromLord Howe Island.Together with the neighbouringPhillip IslandandNepean Island,the three islands collectively form theTerritory of Norfolk Island.[11]At the2021 census,it had 2,188 inhabitants living on a total land area of about 35 km2(14 sq mi).[7]Its capital and administrative seat isKingston,while its main town and largest settlement isBurnt Pine.

EastPolynesianswere the first to settle Norfolk Island, but they had already departed whenGreat Britainsettled it as part of its 1788 colonisation of Australia. The island served as aconvict penal settlementfrom 6 March 1788 until 5 May 1855, except for an 11-year hiatus between 15 February 1814 and 6 June 1825,[12][13]when it lay abandoned. On 8 June 1856, permanent civilian residence on the island began when descendants of theBountymutineerswere relocated fromPitcairn Island.In 1914, the UK handed Norfolk Island over to Australia to administer as anexternal territory.[14]

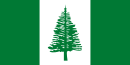

Native to the island, the evergreenNorfolk Island pineis a symbol of the island and is pictured on itsflag.The pine is a key export for Norfolk Island, being a popular ornamental tree in Australia (where two related species grow), and also worldwide.

History

editEarly settlement

editNorfolk Island was uninhabited when first settled by Europeans, but evidence of earlier habitation was obvious. Archaeological investigation suggests that in the 13th or 14th century the island was settled by EastPolynesianseafarers, either from theKermadec Islandsnorth of mainland New Zealand, or from theNorth Islandof New Zealand. However, both Polynesian andMelanesianartefacts have been found, so it is possible that people fromNew Caledonia,relatively close to the north, also reached Norfolk Island. Human occupation must have ceased at least a few hundred years before Europeans arrived in the late 18th century. Ultimately, the relative isolation of the island, and its poorhorticulturalenvironment, were not favourable to long-term settlement.[15]

First penal settlement (1788–1814)

editThe first European known to have sighted and landed on the island was CaptainJames Cook,on 10 October 1774,[12][13]on his second voyage to the South Pacific onHMSResolution.He named it afterMary Howard, Duchess of Norfolk.[16]SirJohn Callargued the advantages of Norfolk Island in that it was uninhabited and thatNew Zealand flaxgrew there.

After the outbreak of theAmerican Revolutionary Warin 1775 haltedpenal transportationto theThirteen Colonies,British prisons started toovercrowd.Several stopgap measures proved ineffective, and the government announced in December 1785 that it would send convicts to parts of what is now known as Australia. In 1786, it included Norfolk Island as an auxiliary settlement, as proposed by John Call, in its plan for colonisation of theColony of New South Wales.The decision to settle Norfolk Island was taken after EmpressCatherine II of Russiarestricted the sale ofhemp.[17]At the time, practically all the hemp and flax required by the Royal Navy for cordage and sailcloth was imported from Russia.

When theFirst Fleetarrived atPort Jacksonin January 1788, GovernorArthur Phillipordered LieutenantPhilip Gidley Kingto lead a party of 15 convicts and seven free men to take control of Norfolk Island, and prepare for its commercial development. They arrived on 6 March. During the first year of the settlement, which was also called "Sydney" like its parent, more convicts and soldiers were sent to the island from New South Wales. Robert Watson, harbourmaster, arrived with the First Fleet as quartermaster ofHMSSirius,and was still serving in that capacity when the ship was wrecked at Norfolk Island in 1790. Next year, he obtained and cultivated a grant of 60 acres (24 ha) on the island.[18]

As early as 1794, Lieutenant-Governor of New South WalesFrancis Grosesuggested its closure as a penal settlement, as it was too remote and difficult for shipping and too costly to maintain.[19]The first group of people left in February 1805, and by 1808, only about 200 remained, forming a small settlement until the remnants were removed in 1813. A small party remained to slaughter stock and destroy all buildings, so that there would be no inducement for anyone, especially from other European powers, to visit and lay claim to the place. From February 1814 until June 1825, the island was uninhabited.

Second penal settlement (1824–1856)

editIn 1824, the British government instructed the Governor of New South Wales,Thomas Brisbane,to reoccupy Norfolk Island as a place to send "the worst description of convicts". Its remoteness, previously seen as a disadvantage, was now viewed as an asset for the detention of recalcitrant male prisoners. The convicts detained have long been assumed to be hardcore recidivists, or 'doubly-convicted capital respites' – that is, men transported to Australia who committed fresh crimes in the colony for which they were sentenced to death, but were spared the gallows on condition of life on Norfolk Island. However, a 2011 study, using a database of 6,458 Norfolk Island convicts, has demonstrated that the reality was somewhat different: More than half were detained on Norfolk Island without ever receiving a colonial conviction, and only 15% had been reprieved from a death sentence. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of convicts sent to Norfolk Island had committed non-violent property offences, and the average length of detention there was three years.[20]Nonetheless, Norfolk Island went through periods of unrest with convicts staging a number ofuprisings and mutiniesbetween 1826 and 1846, all of which failed.[21]The British government began to wind down the second penal settlement after 1847, and the last convicts were removed toTasmaniain May 1855. The island was abandoned because transportation from the United Kingdom toVan Diemen's Land(Tasmania) had ceased in 1853, to be replaced bypenal servitudein the UK.

Settlement by Pitcairn Islanders (1856–present)

editThe next settlement began on 8 June 1856, as the descendants of Tahitians and theHMSBountymutineers, including those ofFletcher Christian,were resettled from thePitcairn Islands,which had become too small for their growing number. On 3 May 1856, 193 people left Pitcairn Islands aboard theMorayshire.[22]On 8 June 194 people arrived, a baby having been born in transit.[23]The Pitcairners occupied many of the buildings remaining from the penal settlements, and gradually established traditional farming and whaling industries on the island. Although some families decided to return to Pitcairn in 1858 and 1863, the island's population continued to grow. They accepted additional settlers, who often arrived on whaling vessels.

The island was a regular resort for whaling vessels in theage of sail.The first such ship was theBritanniain November 1793. The last on record was theAndrew Hicksin August–September 1907.[24]They came for water, wood and provisions, and sometimes they recruited islanders to serve as crewmen on their vessels.

In 1867, the headquarters of theMelanesian Missionof theChurch of Englandwas established on the island. In 1920, the Mission was relocated from Norfolk Island to theSolomon Islandsto be closer to the focus of population.

Norfolk Island was the subject of several experiments in administration during the century. It began the 19th century as part of the Colony of New South Wales. On 29 September 1844, Norfolk Island was transferred from the Colony of New South Wales to the Colony of Van Diemen's Land.[25]: Recital 2 On 1 November 1856 Norfolk Island was separated from the Colony of Tasmania (formerly Van Diemen's Land) and constituted as a "distinct and separate Settlement, the affairs of which should until further Order in that behalf by Her Majesty be administered by a Governor to be for that purpose appointed".[26][27]TheGovernor of New South Waleswas constituted as the Governor of Norfolk Island.[25]: Recital 3

On 19 March 1897, the office of the Governor of Norfolk Island was abolished and responsibility for the administration of Norfolk Island was vested in the Governor of the Colony of New South Wales. Yet, the island was not made a part of New South Wales and remained separate. The Colony of New South Wales ceased to exist upon the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901, and from that date responsibility for the administration of Norfolk Island was vested in the Governor of the State of New South Wales.[25]: Recitals 7 and 8

20th century

editTheParliament of the Commonwealth of Australiaaccepted the territory by theNorfolk Island Act 1913(Cth),[14]: p 886 [25]subject to British agreement; the Act received royal assent on 19 December 1913. In preparation for the handover, a proclamation by theGovernor of New South Waleson 23 December 1913 (in force when gazetted on 24 December) repealed "all laws heretofore in force in Norfolk Island" and replaced them by re-enacting a list of such laws.[28]Among those laws was theAdministration Law 1913(NSW), which provided for appointment of an Administrator of Norfolk Island and of magistrates, and contained a code of criminal law.[29]

British agreement was expressed on 30 March 1914, in a UKOrder in Council[30]made pursuant to theAustralian Waste Lands Act1855 (Imp).[26][14]: p 886 A proclamation by theGovernor-General of Australiaon 17 June 1914 gave effect to the Act and the Order as from 1 July 1914.[30]

DuringWorld War II,the island became a keyairbaseand refuelling depot betweenAustraliaandNew Zealandand betweenNew Zealandand theSolomon Islands.The airstrip was constructed by Australian, New Zealand and United States servicemen during 1942.[31]Since Norfolk Island fell within New Zealand's area of responsibility, it was garrisoned by aNew Zealand Armyunit known asN Forceat a large army camp that had the capacity to house a 1,500-strong force. N Force relieved a company of theSecond Australian Imperial Force.The island proved too remote to come under attack during the war, and N Force left the island in February 1944.

In 1979, Norfolk Island was granted limited self-government by Australia, under which the island elected a government that ran most of the island's affairs.[32]

21st century

editIn 2006, a formal review process took place in which the Australian government considered revising the island's model of government. The review was completed on 20 December 2006, when it was decided that there would be no changes in the governance of Norfolk Island.[33]

Financial problems and a reduction in tourism led to Norfolk Island's administration appealing to the Australian federal government for assistance in 2010. In return, the islanders were to pay income tax for the first time but would be eligible for greater welfare benefits.[34]However, by May 2013, agreement had not been reached and islanders were having to leave to find work and welfare.[35]An agreement was finally signed in Canberra on 12 March 2015 to replace self-government with a local council but against the wishes of the Norfolk Island government.[36][37]A majority of Norfolk Islanders objected to the Australian plan to make changes to Norfolk Island without first consulting them and allowing their say, with 68% of voters against forced changes.[38]An example of growing friction between Norfolk Island and increased Australian rule was featured in a 2019 episode of Discovery Channel's annualShark Week.The episode featured Norfolk Island's policy of culling growing cattle populations by killing older cattle and feeding the carcasses totiger sharkswell off the coast. This is done to help prevent tiger sharks from coming further toward shore in search of food. Norfolk Island holds one of the largest populations of tiger sharks in the world. Australia has banned the culling policy as cruelty to animals. Norfolk Islanders fear this will lead to increased shark attacks and damage an already waning tourist industry.

On 4 October 2015, the time zone for Norfolk Island was changed fromUTC+11:30toUTC+11:00.[39]

Reduced autonomy 2016

editIn March 2015, the Australian Government announced comprehensive reforms for Norfolk Island.[40]The action was justified on the grounds it was necessary "to address issues of sustainability which have arisen from the model of self-government requiring Norfolk Island to deliver local, state and federal functions since 1979".[40]On 17 June 2015, the Norfolk Island Legislative Assembly was abolished, with the territory becoming run by an Administrator and an advisory council. Elections for a new Regional Council were held on 28 May 2016, with the new council taking office on 1 July 2016.[41]

From that date, most Australian Commonwealth laws were extended to Norfolk Island. This means that taxation, social security, immigration, customs and health arrangements apply on the same basis as in mainland Australia.[40]Travel between Norfolk Island and mainland Australia became domestic travel on 1 July 2016.[42]For the2016 Australian federal election,328 people on Norfolk Island voted in theACTelectorate of Canberra,out of 117,248 total votes.[43]Since 2018, Norfolk Island is covered by theelectorate of Bean.[44]

There is opposition to the reforms, led by Norfolk Island People for Democracy Inc., an association appealing to the United Nations to include the island on its list of "non-self-governing territories".[45][46]There has also been movement to join New Zealand since the autonomy reforms.[47]

In October 2019, the Norfolk Island People For Democracy advocacy group conducted a survey of 457 island residents (about one quarter of the entire population) and found that 37% preferredfree associationwith New Zealand, 35% preferred free association with Australia, 25% preferredfull independence,and 3% preferred full integration with Australia.[48][49]

Geography

editThis sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(June 2018) |

The Territory of Norfolk Island is located in the South Pacific Ocean, east of the Australian mainland. Norfolk Island itself is the main island of the island group that the territory encompasses and is located at29°02′S167°57′E/ 29.033°S 167.950°E.It has an area of 34.6 square kilometres (13.4 sq mi), with no large-scale internal bodies of water and 32 km (20 mi) of coastline. Norfolk was formed from several volcanic eruptions between 3.1 and 2.3 million years ago.[50]

The island's highest point isMount Batesreaching 319 metres (1,047 feet)above sea level,located in the northwest quadrant of the island. The majority of the terrain is suitable for farming and other agricultural uses. Phillip Island, the second largest island of the territory, is located at29°07′S167°57′E/ 29.117°S 167.950°E,seven kilometres (4.3 miles) south of the main island.

The coastline of Norfolk Island consists, to varying degrees, of cliff faces. A downward slope exists towards Slaughter Bay and Emily Bay, the site of the original colonial settlement of Kingston. There are no safe harbour facilities on Norfolk Island, with loadingjettiesexisting at Kingston and Cascade Bay. All goods not domestically produced are brought in by ship, usually to Cascade Bay. Emily Bay, protected from the Pacific Ocean by a small coral reef, is the only safe area for recreational swimming, although surfing waves can be found at Anson and Ball Bays.

The climate is subtropical and mild, with little seasonal differentiation. The island is the eroded remnant of abasalticvolcanoactive around 2.3 to 3 million years ago,[51]with inland areas now consisting mainly of rolling plains. It forms the highest point on theNorfolk Ridge,part of the submerged continentZealandia.

The area surrounding Mount Bates is preserved as theNorfolk Island National Park.The park, covering around 10% of the land of the island, contains remnants of the forests which originally covered the island, including stands of subtropicalrainforest.

The park also includes the two smaller islands to the south of Norfolk Island,Nepean IslandandPhillip Island.The vegetation of Phillip Island was devastated due to the introduction during the penal era of pest animals such as pigs and rabbits, giving it a red-brown colour as viewed from Norfolk; however,pest controland remediation work by park staff has recently brought some improvement to the Phillip Island environment.

The major settlement on Norfolk Island isBurnt Pine,located predominantly along Taylors Road, where the shopping centre, post office, bottle shop, telephone exchange and community hall are located. Settlement also exists over much of the island, consisting largely of widely separated homesteads.

Government House,the official residence of the Administrator, is located on Quality Row in what was the penal settlement of Kingston. Other government buildings, including the court, Legislative Assembly and Administration, are also located there. Kingston's role is largely a ceremonial one, however, with most of the economic impetus coming from Burnt Pine.

Climate

editNorfolk Island has a maritime-influencedhumid subtropical climate(Köppen:Cfa) with warm, humid summers and very mild, rainy winters. The highest recorded temperature is 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) on 23 January 2024, whilst the lowest is 6.2 °C (43.2 °F) on 29 July 1953.[52]The island has moderate rainfall 1,109.9 millimetres (43.70 in), with a maximum in winter, and 52.8 clear days annually.[53]

| Climate data forNorfolk Island Airport(29º03'S, 167º56'E, 112 m AMSL) (1991-2020 normals, extremes 1939-2024) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.5 (83.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

27.9 (82.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

6.2 (43.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 80.3 (3.16) |

86.8 (3.42) |

106.8 (4.20) |

95.4 (3.76) |

101.5 (4.00) |

120.6 (4.75) |

122.5 (4.82) |

99.6 (3.92) |

78.4 (3.09) |

62.0 (2.44) |

72.0 (2.83) |

83.9 (3.30) |

1,109.9 (43.70) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.7 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 12.2 | 13.0 | 13.6 | 12.2 | 9.4 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 117.5 |

| Average afternoonrelative humidity(%) | 71 | 72 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 68 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 67 | 70 | 69 |

| Averagedew point°C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 238.7 | 203.4 | 204.6 | 198.0 | 189.1 | 168.0 | 186.0 | 223.2 | 219.0 | 241.8 | 249.0 | 241.8 | 2,562.6 |

| Percentpossible sunshine | 56 | 55 | 54 | 58 | 57 | 54 | 57 | 65 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 56 | 58 |

| Source:Bureau of Meteorology(1991-2020 normals, extremes 1939-2024)[54][55] | |||||||||||||

Environment

editNorfolk Island is part of theInterim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australiaregion "Pacific Subtropical Islands" (PSI), and forms subregion PSI02, with an area of 3,908 hectares (9,660 acres).[56]The country is home to theNorfolk Island subtropical foreststerrestrial ecoregion.[57]

Flora

editNorfolk Island has 174 native plants; 51 of them areendemic.At least 18 of the endemic species are rare or threatened.[58]The Norfolk Island palm (Rhopalostylis baueri) and the smooth tree-fern (Cyathea brownii), the tallest tree-fern in the world,[58]are common in the Norfolk Island National Park but rare elsewhere on the island. Before European colonisation, most of Norfolk Island was covered with subtropical rain forest, the canopy of which was made ofAraucaria heterophylla(Norfolk Island pine) in exposed areas, and thepalmRhopalostylis baueriandtree fernsCyathea browniiandC. australisin moister protected areas. Theunderstorywas thick withlianasand ferns covering the forest floor. Only one small tract, 5 km2(1.9 sq mi), of rainforest remains, which was declared as theNorfolk Island National Parkin 1986.[58]

This forest has been infested with severalintroduced plants.The cliffs and steep slopes of Mount Pitt supported a community of shrubs,herbaceous plants,and climbers. A few tracts of cliff top and seashore vegetation have been preserved. The rest of the island has been cleared for pasture and housing. Grazing and introduced weeds currently threaten the native flora, displacing it in some areas. In fact, there are more weed species than native species on Norfolk Island.[58]

Fauna

editAs a relatively small and isolated oceanic island, Norfolk has few land birds but a high degree of endemicity among them. Norfolk Island is home to a radiation of about 40 endemic snail species.[59][60]Many of the endemic bird species and subspecies have becomeextinctas a result of massive clearance of the island's native vegetation ofsubtropicalrainforestfor agriculture, hunting and persecution as agricultural pests. The birds have also suffered from the introduction of mammals such asrats,cats, foxes, pigs and goats, as well as from introduced competitors such ascommon blackbirdsandcrimson rosellas.[61]Although the island is politically part of Australia, many of Norfolk Island's native birds show affinities to those of neighbouring New Zealand, such as theNorfolk kākā,Norfolk pigeon,[62]andNorfolk boobook.

Extinctions include that of the endemic Norfolk kākā,Norfolk ground doveand Norfolk pigeon, while of the endemic subspecies thestarling,triller,thrushandboobook owlare extinct, although the latter's genes persist in a hybrid population descended from the last female. Other endemic birds are thewhite-chested white-eye,which may be extinct, theNorfolk parakeet,theNorfolk gerygone,theslender-billed white-eyeand endemic subspecies of thePacific robinandgolden whistler.Subfossil bones indicate that a species ofCoenocoryphasnipe was also found on the island and is now extinct, but the taxonomic relationships of this are unclear and have not been scientifically described yet.[61]

The Norfolk Island GroupNepean Islandis also home to breeding seabirds. Theprovidence petrelwas hunted to local extinction by the beginning of the 19th century but has shown signs of returning to breed onPhillip Island.Other seabirds breeding there include thewhite-necked petrel,Kermadec petrel,wedge-tailed shearwater,Australasian gannet,red-tailed tropicbirdandgrey ternlet.Thesooty tern(known locally as the whale bird) has traditionally been subject to seasonal egg harvesting by Norfolk Islanders.[63]

Norfolk Island, with neighbouring Nepean Island, has been identified byBirdLife Internationalas anImportant Bird Areabecause it supports the entire populations of white-chested and slender-billed white-eyes, Norfolk parakeets and Norfolk gerygones, as well as over 1% of the world populations of wedge-tailed shearwaters and red-tailed tropicbirds. Nearby Phillip Island is treated as a separate IBA.[61]

Norfolk Island also has a botanical garden, which is home to a sizeable variety of plant species.[63]However, the island has only one native mammal,Gould's wattled bat(Chalinolobus gouldii). It is very rare, and may already be extinct on the island.

TheNorfolk swallowtail(Papilio amynthor) is a species of butterfly that is found on Norfolk Island and theLoyalty Islands.[64]

Cetaceanswere historically abundant around the island as commercial hunts on the island were operating until 1956. Today, numbers of larger whales have disappeared, but even today many species suchhumpback whale,minke whale,sei whale,and dolphins can be observed close to shore, and scientific surveys have been conducted regularly.Southern right whaleswere once regular migrants to Norfolk,[65]but were severely depleted by historical hunts, and further by recent illegal Soviet and Japanese whaling,[66]resulting in none or very few, if remnants still live, right whales in these regions along withLord Howe Island.

Whale sharkscan be encountered off the island, too.

-

Gannet

-

Masked boobies

-

White tern

-

Emily Bay

-

Norfolk Island pines

-

Captain Cook Lookout

-

Bird Rock (off the north coast)

-

Cathedral Rock (off the north coast)

List of endemic and extirpated native birds

edit- Norfolk parakeet,Cyanoramphus cookii(endangered)

- Norfolk kākā,Nestor productus(extinct)

- Brown goshawk,Accipiter fasciatus(extirpated)

- Norfolk pigeon,Hemiphaga novaseelandiae spadicea(extinct, subspecies of NZ pigeon)

- Norfolk ground dove,Aloepecoenas norfolkensis(extinct)

- Norfolk snipe,Coenocorypha spp.(extinct, undescribed)

- Norfolk rail,Gallirallus spp.(extinct, undescribed)

- Norfolk robin,Petroica multicolor(endangered)

- Norfolk golden whistler,Pachycephala pectoralis xanthoprocta(vulnerable, subspecies of golden whistler)

- Norfolk triller,Lalage leucopyga leucopyga(extinct, nominate subspecies of long-tailed triller)

- Norfolk Island thrush,Turdus poliocephalus poliocephalus(extinct, nominate subspecies of Island thrush)

- Norfolk Island starling,Aplonis fusca fusca(extinct, nominate subspecies of extinct Tasman starling)

- Norfolk boobook,Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata(extinct except for hybrids with nominate subspecies, subspecies of Morepork\Southern boobook)

- White-chested white-eye,Zosterops albogularis(critically endangered, possibly extinct)

- Slender-billed white-eye,Zosterops tenuirostris(near threatened)

- Norfolk gerygone,Gerygone modesta(near threatened)

- Norfolk grey fantail,Rhiphidura albiscapa pelzelni(least concern, subspecies of grey fantail)

- Norfolk petrel,Pterodroma spp.(extinct, undescribed)

Demographics

editThe population of Norfolk Island was 2,188 in the 2021 census,[7]which had declined from a high of 2,601 in 2001.

In 2011, residents were 78% of the census count, with the remaining 22% being visitors. 16% of the population were 14 years and under, 54% were 15 to 64 years, and 24% were 65 years and over. The figures showed an ageing population, with many people aged 20–34 having moved away from the island.[67]

Most islanders are of eitherEuropean-only (mostly British) or combined European-Tahitianancestry, being descendants of theBountymutineersas well as more recent arrivals from Australia and New Zealand. About half of the islanders can trace their roots back toPitcairn Island.[68]

This common heritage has led to a limited number of surnames among the islanders – a limit constraining enough that the island's telephone directory also includes nicknames for many subscribers, such as Carrots, Dar Bizziebee, Diddles, Geek, Lettuce Leaf, Possum, Pumpkin, Smudgie, Truck and Wiggy.[68][69]

Structure of the population

edit| Age group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1 082 | 1 220 | 2 302 | 100 |

| 0–4 | 53 | 53 | 106 | 4.60 |

| 5–9 | 63 | 60 | 123 | 5.34 |

| 10–14 | 69 | 63 | 132 | 5.73 |

| 15–19 | 35 | 38 | 73 | 3.17 |

| 20–24 | 20 | 21 | 41 | 1.78 |

| 25–29 | 19 | 41 | 60 | 2.61 |

| 30–34 | 48 | 52 | 100 | 4.34 |

| 35–39 | 56 | 71 | 127 | 5.52 |

| 40–44 | 64 | 82 | 146 | 6.34 |

| 45–49 | 81 | 86 | 167 | 7.25 |

| 50–54 | 86 | 94 | 180 | 7.82 |

| 55–59 | 103 | 129 | 232 | 10.08 |

| 60–64 | 120 | 142 | 262 | 11.38 |

| 65–69 | 99 | 106 | 205 | 8.91 |

| 70–74 | 70 | 72 | 142 | 6.17 |

| 75–79 | 49 | 47 | 96 | 4.17 |

| 80–84 | 24 | 34 | 58 | 2.52 |

| 85+ | 23 | 29 | 52 | 2.26 |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 185 | 176 | 361 | 15.68 |

| 15–64 | 632 | 756 | 1 388 | 60.30 |

| 65+ | 265 | 288 | 553 | 24.02 |

Population

- 1748(as of the 2016 census)

Population growth rate

- 0.01%

Ancestry[71]

- Australian (22.8%)

- English (22.4%)

- Pitcairn Islander (20%)

- Scottish (6%)

- Irish (5.2%)

Citizenship(as of the 2011 census)

- Australia 79.5%

- New Zealand13.3%

- Fiji2.5%

- Philippines1.1%

- United Kingdom1%

- Other 1.8%

- Unspecified 0.8%

Religion

edit62% of the islanders are Christians. After the death of the first chaplainRev G. H. Nobbsin 1884, aMethodistchurch was formed, followed in 1891 by aSeventh-day Adventistcongregation led by one of Nobbs' sons. Some unhappiness with G. H. Nobbs, the more organised and formal ritual of theChurch of Englandservice arising from the influence of theMelanesian Mission,decline in spirituality, the influence of visiting American whalers, literature sent by Christians overseas impressed by the Pitcairn story, and the adoption of Seventh-day Adventism by the descendants of the mutineers still on Pitcairn, all contributed to these developments.

TheRoman Catholic Churchbegan an ongoing presence on Norfolk Island in 1957.[72]In the late 1990s, a group left the former Methodist (then Uniting Church) and formed acharismaticfellowship. In the 2021 Census, 22% of the ordinary residents identified asAnglican(compared to 34% in 2011), 13% asUniting Church,11% as Roman Catholic and 3% as Seventh-day Adventist. 9% were from other religions. 35.7% had no religion (up from 24% in 2011), and 14.7% did not indicate a religion.[67][73]Typical ordinary congregations in any church do not exceed 30 local residents as of 2010[update].The three older denominations have good facilities. Ministers are usually short-term visitors.

There are two Anglican churches on Norfolk Island, being All Saints Kingston (established 1870)[74]and St Barnabas Chapel (establish 1880 as the Melanesian Mission)[75]which are both part of theDiocese of Sydney, Anglican Church of Australia.[76]

There is one Roman Catholic church on Norfolk Island, the Church ofSt Philip Howardwithin theArchdiocese of Sydney.[72]

Statistics in 2016 Census:[77]

- Protestant46.8%

- Anglican29.2%

- Uniting Church in Australia9.8%

- Seventh-Day Adventist2.7%

- Roman Catholic12.6%

- Other 1.4%

- None 26.7%

- Unspecified 9.5%

Country of birth

editAll information below is from the 2016 Census.[71]

- Australia (39.7%)

- Norfolk Island (22.1%)

- New Zealand (17.6%)

- Fiji (2.7%)

- England (2.6%)

- Philippines (2.3%)

Language

editIslanders speak both English and acreole languageknown asNorfuk,a blend of 18th-century English andTahitian,based onPitkern.The Norfuk language is decreasing in popularity as more tourists visit the island, and more young people leave for work and education. However, efforts are being made to keep it alive via dictionaries and the renaming of some tourist attractions to their Norfuk equivalents.

In 2004, an act of the Norfolk Island Assembly made Norfuk a co-official language of the island.[3][78][79]The act is long-titled: "An Act to recognise the Norfolk Island Language (Norf'k) as an official language of Norfolk Island". The "language known as 'Norf'k'" is described as the language "that is spoken by descendants of the first free settlers of Norfolk Island who were descendants of the settlers of Pitcairn Island". The act recognises and protects use of the language but does not require it; in official use, it must be accompanied by an accurate translation into English.[80][81]32% of the total population reported speaking a language other than English in the 2011 census, and just under three-quarters of the ordinarily resident population could speak Norfuk.[67]

| Language | 2016 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| English | 45.5% | 52.4% |

| Norfuk | 40.9% | 30.5% |

| Fijian | 2.0% | 1.2% |

| Tagalog | 1.0% | 0.8% |

| Filipino | 0.8% | 0.5% |

| Mandarin Chinese | 0.7% | 0.5% |

Education

editThe sole school on the island, Norfolk Island Central School, provides education fromkindergartenthrough to Year 12. The school had acontractualarrangement referred to as aMemorandum of Understandingwith the New South WalesDepartment of Educationregarding the provision of education services at the school, the latest of which took effect in January 2015.[83]In 2015 enrolment at the Norfolk Island Central School was282students.[84]As of January, 2022,The Department of Education (Queensland)took over the running of the Norfolk Island Central School in line with the transition of state services from the New South Wales Government to the Queensland Government. The NSW curriculum will continue to be utilised until the end of the 2023 school year.[85]

Children on the island learn English as well as Norfuk, in efforts to revive the language.[86]

No public tertiary education infrastructure exists on the island. The Norfolk Island Central School works in partnership withregistered training organisations(RTOs) and local employers to support students accessingVocational Education and Training(VET) courses.[87]

Culture

editThis sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(December 2021) |

While there was no "indigenous" culture on the island at the time of settlement, the Tahitian influence of the Pitcairn settlers has resulted in some aspects of Polynesian culture being adapted to that of Norfolk, including thehuladance. Local cuisine also shows influences from the same region.

Islanders traditionally spend a lot of time outdoors, with fishing and other aquatic pursuits being common pastimes, an aspect which has become more noticeable as the island becomes more accessible to tourism. Most island families have at least one member involved in primary production in some form.

Religious observance remains an important part of life for some islanders, particularly the older generations, but actual attendance is about 8% of the resident population plus some tourists. In the 2006 census, 19.9% had no religion[88]compared with 13.2% in 1996.[89]Businesses are closed on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons and Sundays.[31]

One of the island's long-term residents was the novelistColleen McCullough,whose works includeThe Thorn Birdsand theMasters of Romeseries as well asMorgan's Run,set, in large part, on Norfolk Island.Ruth Park,notable author ofThe Harp in the Southand many other works of fiction, also lived on the island for several years after the death of her husband, writer D'Arcy Niland. Actress/singerHelen Reddyalso moved to the island in 2002, and maintained a house there.[90]

American novelistJames A. Michener,who served in theUnited States Navyduring World War II, set one of the chapters of his episodic novelTales of the South Pacificon Norfolk Island.

The island is one of the few locations outside North America to celebrate the holiday ofThanksgiving.[91]

Norfolk Island has a number of museums and heritage organisations, includingNorfolk Island MuseumandBounty Museum.The former has five sites within theKingston and Arthur's Vale Historic Area,a World Heritage Site also linked to theAustralian Convict Sites.[92][93][94]

Cuisine

editThe cuisine of Norfolk Island is very similar to that of thePitcairn Islands,as Norfolk Islanders trace their origins to Pitcairn. The local cuisine is a blend ofBritish cuisineandTahitian cuisine.[95][96]

Recipes from Norfolk Island of Pitcairn origin include mudda (green banana dumplings) and kumara pilhi.[97][98]The island's cuisine also includes foods not found on Pitcairn, such as chopped salads and fruit pies.[99]

Government and politics

editNorfolk Island was the only non-mainlandAustralian territoryto have had self-governance. TheNorfolk Island Act 1979,passed by theParliament of Australiain 1979, is the Act under which the island was governed until the passing of theNorfolk Island Legislation Amendment Act2015 (Cth).[100]TheAustralian governmentmaintains authority on the island through anAdministrator,currently George Plant.[101]

From 1979 to 2015, aLegislative Assemblywas elected by popular vote for terms of not more than three years, although legislation passed by the Australian Parliament could extend its laws to the territory at will, including the power to override any laws made by the assembly. The Assembly consisted of nine seats, with electors casting nine equal votes, of which no more than two could be given to any individual candidate. It is a method of voting called a "weightedfirst past the postsystem ". Four of the members of the Assembly formed theExecutive Council,which devised policy and acted as an advisory body to the Administrator. The last Chief Minister of Norfolk Island wasLisle Snell.Other ministers included: Minister for Tourism, Industry and Development; Minister for Finance; Minister for Cultural Heritage and Community Services; and Minister for Environment.

All seats were held by independent candidates. Norfolk Island did not embrace party politics. In 2007, a branch of theAustralian Labor Partywas formed on Norfolk Island, with the aim of reforming the system of government.

Since 2018, residents of Norfolk Island have been required to enroll in theDivision of Bean.As is the case for all Australian citizens, enrolment and voting for Norfolk Islanders is compulsory.[102]

Disagreements over the island's relationship with Australia were put in sharper relief by a 2006 review undertaken by the Australian government.[33]Under the more radical of two models proposed in the review, the island's legislative assembly would have been reduced to the status of alocal council.[68]However, in December 2006, citing the "significant disruption" that changes to the governance would impose on the island's economy, the Australian government ended the review leaving the existing governance arrangements unaltered.[103]

In a move that apparently surprised many islanders, the Chief Minister of Norfolk Island, David Buffett, announced on 6 November 2010 that the island would voluntarily surrender its self-government status in return for a financial bailout from the federal government to cover significant debts.[104]

It was announced on 19 March 2015 that self-governance for the island would be revoked by the Commonwealth and replaced by a local council with the state ofNew South Walesproviding services to the island. A reason given was that the island had never gained self-sufficiency and was being heavily subsidised by the Commonwealth, being given $12.5 million in 2015 alone. It meant that residents would have to start paying Australian income tax, but they would also be covered by Australian welfare schemes such as Centrelink and Medicare.[105]

The Norfolk Island Legislative Assembly decided to hold areferendumon the proposal. On 8 May 2015, voters were asked if Norfolk Islanders should freely determine their political status and their economic, social and cultural development, and to "be consulted at referendum or plebiscite on the future model of governance for Norfolk Island before such changes are acted upon by the Australian parliament".[106]68% out of 912 voters voted in favour. The Norfolk Island Chief Minister, Lisle Snell, said that "the referendum results blow a hole in Canberra's assertion that the reforms introduced before the Australian Parliament that propose abolishing the Legislative Assembly and Norfolk Island Parliament were overwhelmingly supported by the people of Norfolk Island".[38]

TheNorfolk Island Legislation Amendment Act 2015passed theAustralian Parliamenton 14 May 2015 (assented on 26 May 2015), abolishing self-government on Norfolk Island and transferring Norfolk Island into acouncilas part of New South Wales law.[100]

Between 1 July 2016 and 1 January 2022, New South Wales provided state-based services. Since 1 January 2022, Queensland has provided state-based services directly for Norfolk Island.[107]

The island's official capital isKingston;it is, however, more a centre of government than a sizeable settlement. The largest settlement is atBurnt Pine.

The most important local holiday isBounty Day,celebrated on 8 June, in memory of the arrival of the Pitcairn Islanders in 1856.

Local ordinances and acts apply on the island, where most laws are based on the Australian legal system. Australian common law applies when not covered by either Australian or Norfolk Island law.Suffrageis universal at age eighteen.

As a territory of Australia, Norfolk Island does not have diplomatic representation abroad, or within the territory, and is also not a participant in any international organisations, other than sporting organisations.

Theflagis three vertical bands of green, white, and green with a large green Norfolk Island pine tree centred in the slightly wider white band.

TheNorfolk Island Regional Councilwas established in July 2016 to govern the territory at the local level in line withlocal governments in mainland Australia.

Constitutional status

editFrom 1788 until 1844, Norfolk Island was a part of theColony of New South Wales.In 1844, it was severed from New South Wales and annexed to the Colony ofVan Diemen's Land.[25]: Recital 2 With the demise of the third settlement and in contemplation that the inhabitants of Pitcairn Island would move to Norfolk Island,[108][109]theAustralian Waste Lands Act1855 (Imp), gave the Queen in Council the power to "separate Norfolk Island from the Colony of Van Diemen's Land and to make such provision for the government of Norfolk Island as might seem expedient".[26]In 1856, the Queen in Council ordered that Norfolk Island be a distinct and separate settlement, appointing the Governor of New South Wales to also be the Governor of Norfolk Island with "full power and authority to make laws for the order, peace, and good government" of the island.[27]Under these arrangements Norfolk Island was effectively self-governing,[110]Although Norfolk Island was a colony acquired by settlement, it was never within theBritish Settlements Act.[14]: p 885 [111]

The constitutional status of Norfolk Island was revisited in 1894 when the British government appointed an inquiry into the administration of justice on the island.[110]By this time, there had been steps in Australiatowards federationincluding the1891 constitutional convention.There was a correspondence between the Governor of Norfolk Island, the British colonial office and the Governor of New Zealand as to how the island should be governed and by whom. Even within NSW, it was felt that "the laws and system of government in the Colony of New South Wales would not prove suitable to the Island Community".[110]In 1896, the Governor of New Zealand wrote "I am advised that, as far as my Ministers can ascertain, if any change is to take place in the government of Norfolk Island, the Islanders, while protesting against any change, would prefer to come under the control of New Zealand rather than that of New South Wales".[110]

The British government decided not to annex Norfolk Island to the Colony of NSW and instead that the affairs of Norfolk Island would be administered by the Governor of NSW in that capacity rather than having a separate office as Governor of Norfolk Island. The order-in-council contemplated the future annexation of Norfolk Island to the Colony of NSW or to any federal body of which NSW form part.[110][112]Norfolk Island was not a part of NSW and residents of Norfolk Island were not entitled to have their names placed on the NSW electoral roll.[113]Norfolk Island was accepted as a territory of Australia, separate from any state, by theNorfolk Island Act1913 (Cth),[25]passed under the territories power,[114]and made effective in 1914.[30]Norfolk Island was given a limited form of self-government by theNorfolk Island Act1979 (Cth).[32]

There have been four challenges to the constitutional validity of the Australian Government's authority to administer Norfolk Island:

- In 1939, Samuel Hadley argued that the only valid laws in Norfolk Island were those made under the 1856 Order in Council and that all subsequent laws were invalid; his case was rejected by theHigh Court.[115]

- In 1965, theSupreme Court of Norfolk Islandrejected Henry Newbery's appeal against conviction for failing to apply to be enrolled to vote in Norfolk Island Council elections. He had argued that in 1857 Norfolk Island had a constitution and a legislature such that the Crown could not abolish the legislature nor place Norfolk Island under the authority of Australia. In the Supreme Court, Eggleston J considered the constitutional history of Norfolk Island and concluded that theAustralian Waste Lands Act1855 (Imp) authorised any form of government, representative or non-representative, and that this included placing Norfolk Island under the authority of Australia.[109]

- As a result of the Australian Government's decision in 1972 to prevent Norfolk Island from being used as a tax haven, Berwick Ltd claimed to be resident in Norfolk Island but was convicted of failing to lodge a tax return. One of the arguments for Berwick Ltd was that Norfolk Island, as an external territory, was not part of Australia in the constitutional sense. In 1976, the High Court unanimously rejected this argument, approving theNewberydecision and holding that Norfolk Island was a part of Australia.[116]

- In 2004 the Australian Government amended theNorfolk Island Act1979 (Cth) to remove the right for non-Australian citizens to enrol and stand for election to the Legislative Assembly of Norfolk Island.[117]The validity of the amendments was challenged in the High Court, arguing that as an external territory Norfolk Island was not part of Australia in the constitutional sense and that disenfranchising residents of Norfolk Island who were not Australian citizens was inconsistent with self-government. In 2007, the High Court of Australia rejected these arguments, again approving theNewberydecision and holding that Norfolk Island was part of Australia and that self-government did not require residency rather than citizenship to determine the entitlement to vote.[118]

The Government of Australia thus holds that:

- Norfolk Island has been an integral part of the Commonwealth of Australia since 1914, when it was accepted as an Australian territory under section 122 of the Constitution. The Island has no international status independent of Australia.[119]

Much of the self-government under the 1979 legislation was repealed with effect from 2016.[100]The reforms included, to the chagrin of some of the locals of Norfolk Island, a repeal of the preambular sections of the Act which originally were 3–4 pages recognising the particular circumstances in the history of Norfolk Island.[120]

Consistent with the Australian position, the United Nations Decolonization Committee[121]does not include Norfolk Island on its list ofnon-self-governing territories.

This legal position is disputed by some residents on the island. Some islanders claim that Norfolk Island was actually granted independence at the timeQueen Victoriagranted permission to Pitcairn Islanders to re-settle on the island.[122]

Following reforms to the status of Norfolk Island, there were mass protests by the local population.[123]In 2015, it was reported that Norfolk Island was taking its argument for self-governance to the United Nations.[124][125]A campaign to preserve the island's autonomy was formed, named Norfolk's Choice.[126]A formal petition was lodged with the United Nations byGeoffrey Robertsonon behalf of the local population on 25 April 2016.[127]

Various suggestions for retaining the island's self-government have been proposed. In 2006, a UK MP,Andrew Rosindell,raised the possibility of the island becoming a self-governingBritish Overseas Territory.[128]In 2013, the island's last chief minister,Lisle Snell,suggested independence, to be supported by income from fishing, offshore banking and foreign aid.[129]

The laws of Norfolk Island were in a transitional state, under the Norfolk Island Applied Laws Ordinance 2016 (Cth), from 2016 until 2018.[130]Laws of New South Wales as applying in Norfolk Island were suspended (with five major exceptions, which the 2016 Ordinance itself amended) until the end of June 2018. From 1 July 2018, all laws of New South Wales apply in Norfolk Island and, as "applied laws", are subject to amendment, repeal or suspension by federal ordinance.[131][132]The Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) has been amended for application to Norfolk Island.[133]

Immigration and citizenship

editThe island was subject to separate immigration controls from the remainder of Australia. Before 1 July 2016, immigration to Norfolk Island, even by other Australian citizens was heavily restricted.[134]In 2012, immigration controls were relaxed with the introduction of an Unrestricted Entry Permit[135]for all Australian and New Zealand citizens upon arrival and the option to apply for residency; the only criteria were to pass a police check and be able to pay into the local health scheme.[136]From 1 July 2016, the Australian migration systemreplacedthe immigration arrangements previously maintained by the Norfolk Island Government.[137]Holders of Australian visas who travelled to Norfolk Island would have departed theAustralian Migration Zonebefore 1 July 2016. Unless they held a multiple-entry visa, the visa would have ceased; in which case they would require another visa to re-enter mainland Australia.[135][138]

Australian citizens and residents from other parts of the nation now have an automatic right of residence on the island after meeting these criteria (Immigration (Amendment No. 2) Act 2012). Australian citizens can carry either a passport or a form of photo identification to travel to Norfolk Island. TheDocument of Identity,which is no longer issued, is also acceptable within its validity period. Citizens of all other nations must carry a passport to travel to Norfolk Island even if arriving from other parts of Australia.

Non-Australian citizens who are permanent residents of Norfolk Island may apply for Australian citizenship after meeting normal residence requirements and are eligible to take up residence in mainland Australia at any time through the use of a Confirmatory (Residence) visa (subclass 808).[139]Children born on Norfolk Island are Australian citizens as specified byAustralian nationality law.

Health care

editNorfolk Island Hospitalis the only medical centre on the island. Since 1 July 2016, medical treatment on Norfolk Island has been covered byMedicareand thePharmaceutical Benefits Schemeas it is in Australia. Emergency medical treatment is covered by Medicare or a private health insurer.[140]Although the hospital can perform minor surgery, serious medical conditions are not permitted to be treated on the island and patients are flown back to mainland Australia. Air charter transport can cost as much asA$30,000, which is covered by the Australian Government. For serious emergencies,medical evacuationswere provided by theRoyal Australian Air Force;currently this service is provided by Australian Retrieval Services. The island has one ambulance, staffed by one employed St John Officer and a group ofSt John Ambulance Australiavolunteers.

The lack of medical facilities available in most remote communities has a major impact on the health care of Norfolk Islanders.[141]As is consistent with other extremely remote regions, many older residents move to New Zealand or Australia to access the required medical care.

Defence and law enforcement

editDefence is the responsibility of theAustralian Defence Force.There are no active military installations or defence personnel on Norfolk Island. The Administrator may request the assistance of the Australian Defence Force if required. As part of "Operation Resolute", theRoyal Australian NavyandAustralian Border ForcedeployCapeandArmidale-classpatrol boats to carry out civil maritime security operations in Australian mainland and offshore territories including Norfolk Island, theHeard Island and McDonald Islands,Christmas Island,theCocos (Keeling) Islands,Macquarie Island,andLord Howe Island.[142]In part to carry out this mission, as of 2023, the Navy'sArmidale-class boats are in the process of being replaced by largerArafura-class offshore patrol vessels.[143]

In 2023, Australian and American forces conducted jointmilitary exercisesin the vicinity of Norfolk Island signifying the island's potential as a staging base for peacekeeping, disaster-relief and other operations in the South Pacific.[144][145]

Civilian law enforcement and community policing are provided by theAustralian Federal Police.The normal deployment to the island is onesergeantand twoconstables.These are augmented by five local Special Members who have police powers but are not AFP employees.

Courts

editTheNorfolk Island Court of Petty Sessionsis the equivalent of aMagistrates Courtand deals with minor criminal, civil or regulatory matters. The Chief Magistrate of Norfolk Island is usually the current Chief Magistrate of theAustralian Capital Territory.Three localJustices of the Peacehave the powers of a Magistrate to deal with minor matters.

TheSupreme Court of Norfolk Islanddeals with more serious criminal offences, more complex civil matters, administration of deceased estates and federal laws as they apply to the Territory. The Judges of the Supreme Court of Norfolk Island are generally appointed from among Justices of theFederal Court of Australiaand may sit on the Australian mainland or convene acircuit court.Appeals are to the Federal Court of Australia.

As stated by the Legal Profession Act 1993,[146]"a resident practitioner must hold a Norfolk Island practising certificate." As of 2014[update],only one lawyer maintained a full-time legal practice on Norfolk Island.[147]

Census

editUntil 2016, Norfolk Island took its own censuses, separate from those taken by theAustralian Bureau of Statisticsfor the remainder of Australia.[148]

Postal service

editPrior to 2016, theNorfolk Island Postal Servicewas responsible for mail receipt and delivery on the island and issued its own postage stamps. With the merger of Norfolk Island as a regional council, the Norfolk Island Postal Service ceased to exist and all postage is now handled byAustralia Post.[149]Australia Post sends and receives mail from Norfolk Island with the postcode 2899.

Economy and infrastructure

editTourism, the primary economic activity, has steadily increased over the years. As Norfolk Island prohibits the importation of fresh fruit and vegetables, most produce is grown locally. Beef is both produced locally and imported. The island has one winery,Two Chimneys Wines.[150]

The Australian government controls theexclusive economic zone(EEZ) and revenue from it extending 200 nautical miles (370 km) around Norfolk Island equating to roughly 428,000 km2(165,000 sq mi), and territorial sea claims to 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) from the island. There is a strong belief on the island that some of the revenue generated from Norfolk's EEZ should be available to provide services such as health and infrastructure on the island, which the island has been responsible for, similar to how the Northern Territory is able to access revenue from their mineral resources.[151]The exclusive economic zone provides the Islanders with fish, its only major natural resource. Norfolk Island has no direct control over any marine areas but has an agreement with the Commonwealth through theAustralian Fisheries Management Authority(AFMA) to fish "recreationally" in a small section of the EEZ known locally as "the Box". While there is speculation that the zone may include oil and gas deposits, this is not proven.[68]There are no major arable lands or permanent farmlands, though about 25 percent of the island is a permanent pasture. There is no irrigated land. The island uses the Australian dollar as its currency.

In 2015, a company in Norfolk Island was granted a licence to export medicinal cannabis.[152]The medicinal cannabis industry has been viewed by some as a means of reinvigorating the economy of Norfolk Island. The Commonwealth stepped in to overturn the decision, with the island's administrator, former Liberal MP Gary Hardgrave revoking the local licence to grow the crop.[153](Legislation to allow the cultivation of cannabis in Australia for medical or scientific purposes passed Federal Parliament in February 2016.[154]The Victorian Government will be undertaking a small-scale, strictly controlled cannabis cultivation trial at a Victorian research facility.[155])

Taxes

editFormerly, residents of Norfolk Island did not pay Australian federal taxes,[156]which created atax havenfor locals and visitors alike. There was noincome taxso the island's legislative assembly raised money through animport duty,fuel levy, medicare levy,goods and services taxof 12%, and local/international phone calls.[68][156]The Chief Minister of Norfolk Island, David Buffett, announced on 6 November 2010 that the island would voluntarily surrender its tax-free status in return for a financial bailout from the federal government to cover significant debts. The introduction of income taxation came into effect on 1 July 2016. Prior to these reforms, residents of Norfolk Island were not entitled to social services.[157]The reforms extend to private persons, companies and trustees.[158][159]

Communications

editAs of 2004[update],2532telephone main lines were in use, a mix of analogue (2500) and digital (32) circuits.[6]Satellite communications servicesare planned.[160]The island has two locally based radio stations (Radio Norfolk), a government run station broadcasting on both AM and FM frequencies and an independent station 87.6 FM owned by the Bounty Museum Trust.[161]Norfolk Island does not have its own dedicatedABC Local Radiostation but the island is covered byABC Western Plainswhich broadcasts on 95.9 FM from its studios inDubboin mainland Australia. There is also one television station, Norfolk TV, featuring local programming, plus transmitters for Australian channelsABC,SBS,Nine(throughImparja Television) andSeven.[162]The Internetcountry codetop-level domain(ccTLD) is.nf.[163]A smallGSM(2G) mobile network operates on the island across three towers, however no data transmission is available on this network. An eight-tower 4G/LTE 1800 MHz network was installed in November 2018, improving data service significantly on the island.[164][165]

Transport

editThere are no railways, waterways, ports or harbours on the island.[166]Loadingjettiesare located at Kingston and Cascade, but ships cannot get close to either of them. When a supply ship arrives, it isemptied by whaleboatstowed by launches, five tonnes at a time. A mobile crane picks up the freight using nets and straps and lifts the freight onto the pier. Which jetty is used depends on the prevailing weather of the day; the jetty on the leeward side of the island is often used. If the wind changes significantly during unloading/loading, the ship will move around to the other side. Visitors often gather to watch the activity when a supply ship arrives.[citation needed]Norfolk Forwarding Services is the primary Freight Forwarding service for Norfolk Island handling both sea and airfreight. In 2017 Norfolk Forwarding Services shipped most of the freight for the Cascade Pier Project over a period of 18 months.[citation needed]

The island hosts 80 kilometres (50 mi) of roads, of which 53 km (33 mi) are paved and 27 km (17 mi) unpaved. As with the rest of Australia, driving is on the left side of the road. Uniquely, local law gives livestock right of way.[68]Speed limits are lower than most mainland Australian roads; the general speed limit is 50 km/h (31 mph), reducing to 40 km/h (25 mph) in town and 30 km/h (19 mph) near schools. Drivers on the island wave to other passing vehicles, this tradition is nicknamed the "Norfolk wave".[167]

There is one airport,Norfolk Island Airport.[6]Qantas operates direct flights toSydneyandBrisbane,andAir Chathamsflies to Auckland. A local airline,Norfolk Island Airlines,ran flights to Auckland and Brisbane until 2018.[168]In mid 2018, Air Chathams announced it was looking to re-establish flights between Auckland and Norfolk Island.[169]It began a weekly service between Auckland and Norfolk Island on 6 September 2019 using aConvair 580.[citation needed] Since the reopening of the Trans-Tasman bubble in 2021,[170]the Air Chathams Auckland service operates on Thursdays using a 36-seaterSaab 340aircraft.

Electricity

editElectricity is provided by diesel generators operated by Norfolk Island Electricity, a government organisation. Some electricity is also provided by privately owned rooftop solar panels.[171]

Sport

editNorfolk Island competes at theCommonwealth Games,and has won two bronze medals, both inlawn bowls.[172]The territory also competes in thePacific GamesandPacific Mini Games.

The island supports nationalrugby league,cricketandnetballteams. It is a member ofWorld Athletics.[173]

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^Buffett, Alice,An Encyclopædia of the Norfolk Island Language,1999

- ^"The Legislative Assembly of Norfolk Island".Archived fromthe originalon 18 December 2014.Retrieved18 October2014.

- ^ab"Norfolk Island Language (Norf'k) Act 2004".Archived fromthe originalon 25 July 2008.Retrieved6 February2018.

- ^2016 Census QuickStatsArchived2 October 2017 at theWayback Machine– Norfolk Island – Ancestry, top responses

- ^"2021 Norfolk Island, Census All persons QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics".Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2022.Retrieved4 March2023.

- ^abc"Norfolk Island".The World Factbook.Central Intelligence Agency. 16 October 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2021.Retrieved27 October2012.

- ^abcAustralian Bureau of Statistics(28 June 2022)."Norfolk Island (Suburbs and Localities)".2021 Census QuickStats.Retrieved7 July2022.

- ^KPMG (2019).Monitoring the Norfolk Island Economy(PDF).Norfolk Islands: Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development. p. 4.Archived(PDF)from the original on 9 August 2021.Retrieved9 August2021.

- ^Wells, John C.(2008).Longman Pronunciation Dictionary(3rd ed.). Longman.ISBN978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^"NI Arrival Card"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 13 November 2011.Retrieved28 March2013.

- ^"Norfolk Island Act 1979".Federal Register of Legislation.23 May 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2019.Retrieved17 July2019.Schedule 1.

- ^ab"History and Culture on Norfolk Island".Archived fromthe originalon 12 July 2012.Retrieved15 September2016.

- ^ab"Norfolk Island: A Short History".Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2016.

- ^abcdRoberts-Wray, Kenneth (1966).Commonwealth and Colonial Law.London: Stevens.

- ^Anderson, Atholl;White, Peter (2001)."Prehistoric Settlement on Norfolk Island and its Oceanic Context"(PDF).Records of the Australian Museum.27(Supplement 27): 135–141.doi:10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1348.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 March 2016.Retrieved28 April2015.

- ^Channers On Norfolk Island InfoArchived3 November 2021 at theWayback Machine.Channersonnorfolk.com (15 March 2013). Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^Memorandum to Grenville on the Trade of Canada, 4 November 1789, National Archives, Kew, CO 42/66, ff.403-7; cited in Alan Frost,Convicts and Empire, a Naval Question,Melbourne, Oxford UP, 1980, pp.137, 218.

- ^Lea-Scarlett, E. J. (1967)."Watson, Robert (1756–1819)".Australian Dictionary of Biography.Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography,Australian National University.ISBN978-0-522-84459-7.ISSN1833-7538.OCLC70677943.Retrieved7 June2018.

- ^Grose to Hunter, 8 December 1794,Historical Records of New South Wales,Sydney, 1893, Vol.2, p. 275.

- ^Causer, T.' "The Worst Types of Sub-Human Beings": the Myth and Reality of the Convicts of the Norfolk Island Penal SettlementArchived20 April 2012 at theWayback Machine,1825–1855',Islands of History,Sydney, 2011, pp. 8–31.

- ^Cyriax, Oliver (1993).Crime: An Encyclopedia.Andre Deutsch. 9780233988214, pp. 284–285

- ^"Fateful Voyage".Archived fromthe originalon 17 October 2016.Retrieved3 December2018.

- ^"Discover Norfolk Island".Archivedfrom the original on 14 May 2016.

- ^Langdon, Robert (ed.) (1984)Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century,Canberra, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, pp. 194–7.ISBN086784471X

- ^abcdefNorfolk Island Act 1913(Cth).

- ^abcAustralian Waste Lands Act 1855(PDF),archived(PDF)from the original on 12 June 2018,retrieved9 June2018(Imp).

- ^ab"Proclamation – Norfolk Island".NSW Government Gazette.No. 166. 1 November 1856. p. 2815.Archivedfrom the original on 15 February 2023.Retrieved8 June2018– via National Library of Australia.

- ^"Proclamation".NSW Government Gazette.No. 205. 24 December 1913. p. 7659.Archivedfrom the original on 15 February 2023.Retrieved9 June2018– via National Library of Australia.

- ^"Administration Law 1913".NSW Government Gazette.No. 205. 24 December 1913. p. 7663.Archivedfrom the original on 12 June 2018.Retrieved9 June2018– via National Library of Australia.

- ^abc"Proclamation: Norfolk Island Act 1913".Australian Government Gazette.No. 35. 17 June 1914. p. 1043.Archivedfrom the original on 12 June 2018.Retrieved8 June2018..

- ^ab"There's More to Norfolk Island".Archivedfrom the original on 22 April 2016.

- ^abNorfolk Island Act 1979(Cth).

- ^ab"Governance & Administration".Attorney-General's Department. 28 February 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 20 September 2010.

- ^"Norfolk Island is about to undergo a dramatic change in order to secure a financial lifeline".ABC News 7.30 Report. 26 January 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2011.

- ^"Welfare fight forces families from island".The Sydney Morning Herald.5 May 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2013.

- ^"Norfolk Island self-government to be revoked and replaced by local council".The Guardian.19 March 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 11 February 2017.

- ^"'We're not Australian': Norfolk Islanders adjust to shock of takeover by mainland ".The Guardian.21 May 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2017.

- ^ab"Solid 'Yes' vote in referendum on Norfolk Island governance".Radio New Zealand.8 May 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2015.

- ^Hardgrave, Gary (3 September 2015)."Norfolk Island standard time changes 4 October 2015"(Press release).Administrator of Norfolk Island.Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2015.Retrieved4 October2015.

- ^abc"Norfolk Island reform".Regional.gov.au.Archivedfrom the original on 29 August 2016.Retrieved17 July2016.

- ^"Norfolk Island elects its inaugural council".Minister.infrastructure.gov.au. 3 June 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 15 July 2016.Retrieved17 July2016.

- ^Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development – Factsheet: Domestic travel between Norfolk Island and mainland Australia, website. Retrieved 12 November 2016

- ^"Tally room, Canberra ACT".Australian Electoral Commission.Archivedfrom the original on 20 May 2019.Retrieved15 May2019.

- ^Whyte, Sally (6 April 2018)."ACT's new federal electorates revealed".The Sydney Morning Herald.Archivedfrom the original on 15 May 2019.Retrieved15 May2019.

- ^"Norfolk pleads for Canberra to delay NSW absorption".Radionz.co.nz. 18 June 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 23 July 2016.Retrieved17 July2016.

- ^"Norfolk Islanders seeking UN oversight".RNZ.Radionz.co.nz. 28 April 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 23 July 2016.Retrieved17 July2016.

- ^Roy, Eleanor Ainge (23 August 2017)."Norfolk Island should become part of New Zealand, says former chief minister".Guardian Australia.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2017.Retrieved24 September2017.

- ^Julia Hollingsworth (30 October 2019)."Norfolk Island: Why residents want to ditch Australia for New Zealand".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2021.Retrieved13 March2021.

- ^"Survey reveals over 96% of people on Norfolk Island are opposed to the current governance regime imposed by Australia. – Norfolk Island People for Democracy".24 October 2019. Archived fromthe originalon 24 October 2019.Retrieved13 March2021.

- ^Jones, J. G.; McDougall (1973). "Geological history of Norfolk and Philip Islands, southwest Pacific Ocean".Journal of the Geological Society of Australia.20(3): 239–257.Bibcode:1973AuJES..20..239J.doi:10.1080/14400957308527916.

- ^Geological origins,Norfolk Island Tourism. Retrieved 13 April 2007.Archived7 September 2008 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Norfolk Island Aero Climate Statistics".Bureau of Meteorology.Retrieved22 June2024.

- ^"Norfolk Island Aero Climate Statistics".Bureau of Meteorology.Retrieved22 June2024.

- ^"Norfolk Island Aero Climate Statistics".Bureau of Meteorology.Retrieved22 June2024.

- ^"Norfolk Island Aero Climate Statistics".Bureau of Meteorology.Retrieved22 June2024.

- ^"Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA7) regions and codes".Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities.Commonwealth of Australia. 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 31 January 2013.Retrieved13 January2013.

- ^Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017)."An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm".BioScience.67(6): 534–545.doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014.ISSN0006-3568.PMC5451287.PMID28608869.

- ^abcdWorld Wildlife Fund."Norfolk Island subtropical forests".eoearth.org.Archivedfrom the original on 17 January 2008.

- ^Neuweger, D (2001)."Land Snails from Norfolk Island Sites".Records of the Australian Museum.Supplement 27: 115–122.doi:10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1346.

- ^Morgan-Richards, M (2020)."Notes from a small islands – in the Pacific".Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2020.Retrieved28 April2020.

- ^abcBirdlife Data Zone: Norfolk IslandArchived18 February 2015 at theWayback Machine,BirdLife International. (2015). Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^Goldberg, Julia; Trewick, Steven A.; Powlesland, Ralph G. (2011). "Population structure and biogeography of Hemiphaga pigeons (Aves: Columbidae) on islands in the New Zealand region".Journal of Biogeography.38(2): 285–298.Bibcode:2011JBiog..38..285G.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02414.x.ISSN1365-2699.S2CID55640412.

- ^abNorfolk IslandArchived24 October 2012 at theWayback Machineat Australian National Botanic Gardens. Environment Australia: Canberra, 2000.

- ^Braby, Michael F. (2008).The Complete Field Guide to Butterflies of Australia.CSIRO Publishing.ISBN978-0-643-09027-9.

- ^Nichols, Daphne (2006). Lord Howe Island Rising. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Tower Books.ISBN0-646-45419-6.Retrieved 20 November 2015

- ^Berzin A.; Ivashchenko V.Y.; Clapham J.P.; Brownell L.R. Jr. (2008)."The Truth About Soviet Whaling: A Memoir".DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska – Lincoln.Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2016.Retrieved20 November2015.

- ^abc"Norfolk Island Census of Population and Housing: Census Description, Analysis and Basic Tables"(PDF).9 August 2011. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 24 March 2012.Retrieved3 March2012.

- ^abcdef"Battle for Norfolk Island".BBC.18 May 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 24 November 2006.

- ^"Norfolk Island Phone Book".Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2021.Retrieved21 March2022.

- ^"UNSD — Demographic and Social Statistics".unstats.un.org.Archivedfrom the original on 18 February 2023.Retrieved10 May2023.

- ^abc"2016 Census QuickStats: Norfolk Island".Archived fromthe originalon 7 May 2019.Retrieved2 May2021.

- ^ab"St Philip Howard's Catholic Church, Norfolk Island".St Mary's Cathedral Sydney.Archived fromthe originalon 24 March 2024.Retrieved24 March2024.

- ^"2021 Norfolk Island, Census All persons QuickStats".Australian Bureau of Statistics.Archived fromthe originalon 24 March 2024.Retrieved24 March2024.

- ^"All Saints Church".www.norfolkisland.com.au.Archived fromthe originalon 24 March 2024.Retrieved24 March2024.

- ^"St. Barnabas".Norfolk Island Church of England.26 November 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 24 March 2024.Retrieved24 March2024.

- ^"Parish of Norfolk Island".Anglican Church of Australia Directory.Archived fromthe originalon 24 March 2024.Retrieved24 March2024.

- ^"Australia-Oceania:: NORFOLK ISLAND".CIA The World Factbook. 6 October 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2021.Retrieved24 January2021.

- ^The Dominion Post,21 April 2005 (page B3)

- ^Squires, Nick (19 April 2005)."Save our dialect, say Bounty islanders".The Telegraph UK.London.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2014.Retrieved6 April2007.

- ^"About Norfolk – Language".Norfolkisland.com.au.Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2012.Retrieved13 April2012.

- ^"Norfuk declared official language in Norfolk Island – report".Radio New Zealand International. 20 April 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 17 July 2012.Retrieved13 April2012.

- ^"2021 Norfolk Island, Census All persons QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics".www.abs.gov.au.Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2024.Retrieved30 December2023.

- ^Norfolk Island Central SchoolArchived18 May 2015 at theWayback Machine(accessed 13 May 2015)

- ^"Norfolk Island Central School".Archived fromthe originalon 3 June 2016.Retrieved1 May2016.

- ^"Access to the NSW curriculum on Norfolk until 2023"(Press release). The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. 2 December 2021. Archived fromthe originalon 4 August 2023.Retrieved4 August2023.

- ^"Norfolk studies – Norfolk Island Central School".Archived fromthe originalon 2 May 2021.Retrieved2 May2021.

- ^Page 4, Education Review, Norfolk Island, Stage One, Stage Two and Stage Three, The Report, 14 September 2014Archived20 April 2015 at theWayback Machine(accessed 13 May 2015)

- ^"Norfolk Island Census, 2006"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 March 2016.Retrieved17 July2016.

- ^"Norfolk Island Census, 1996"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 March 2016.Retrieved17 July2016.

- ^"Helen Reddy: My island home".Probus South Pacific.12 April 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 26 February 2014.Retrieved17 April2014.

- ^"Norfolk Island Public Holidays 2011 (Oceania)".qppstudio.net.Archived fromthe originalon 27 November 2011.Retrieved6 December2011.

- ^"Bounty Folk Museum | Norfolk Island, Australia & Pacific | Attractions".Lonely Planet.Archivedfrom the original on 29 March 2023.Retrieved29 March2023.

- ^"Norfolk Island Museum | Norfolk Island Museum".norfolkislandmuseum.com.au.Archivedfrom the original on 10 October 2012.Retrieved28 March2023.

- ^Centre, UNESCO World Heritage."Australian Convict Sites".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.Archivedfrom the original on 29 October 2023.Retrieved28 March2023.

- ^"Jasons".Jasons.Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2017.Retrieved9 November2017.

- ^"Norfolk Island Travel Guide – Norfolk Island Tourism – Flight Centre".Archivedfrom the original on 10 November 2017.Retrieved9 November2017.

- ^"The Food of Norfolk Island".www.theoldfoodie.com.Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2018.Retrieved26 July2018.

- ^"Norfolk Island (Norfolk Island Recipes)".www.healthy-life.narod.ru.Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2018.Retrieved26 July2018.

- ^"Homegrown: Norfolk Island".5 July 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2018.Retrieved26 July2018.

- ^abcNorfolk Island Legislation Amendment Act 2015(Cth).

- ^"Norfolk Island Administrator appointment".The Mirage.11 May 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2023.Retrieved3 June2023.

- ^"Australian Electoral Commission: Norfolk Island electors".Medicare.Archivedfrom the original on 2 February 2018.

- ^"Norfolk Island Governance Arrangements"(Press release). Department of Transport and Regional Services. 20 December 2006. Archived fromthe originalon 31 October 2007.

- ^Higgins, Ean."Mutineer descendants opt for bounty".The Australian.Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2010.

- ^Shalailah Medhora (19 March 2015)."Norfolk Island self-government to be replaced by local council".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 11 February 2017.

- ^"Norfolk Island to go ahead with governance referendum".Radio New Zealand.27 March 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^Druce, Alex (26 October 2021)."Why island paradise is switching states".news.com.au.Archivedfrom the original on 26 October 2021.Retrieved26 October2021.

- ^"Ch 5 Historical outline"(PDF),Report of the Royal Commission into matters relating to Norfolk Island,Australian Government, October 1976,archived(PDF)from the original on 12 November 2018,retrieved7 June2018

- ^abNewbery v The Queen(1965) 7FLR34 (25 March 1965),Supreme Court of Norfolk Island.

- ^abcdeKerr, A (2009)."Ch 6: Norfolk Island"(PDF).A Federation in These Seas: An account of the acquisition by Australia of its external territories.Australian Government.Archived(PDF)from the original on 4 April 2018.Retrieved8 June2018.

- ^"British Settlements Act 1887".Government of the United Kingdom.Archivedfrom the original on 12 September 2015.