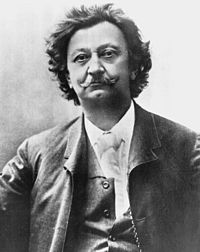

Lazar Kostić(Serbian Cyrillic:Лазар Костић;12 February 1841 – 27 November 1910) was a Serbian poet, prose writer, lawyer,aesthetician,journalist,[1]publicist, and politician who is considered to be one of the greatest minds ofSerbian literature.[2][better source needed]Kostić wrote around 150 lyrics, 20 epic poems, three dramas, one monograph, several essays, short stories, and a number of articles.[3]Kostić promoted the study ofEnglish literatureand together withJovan Andrejević-Joleswas one of the first to begin the systematic translation of the works ofWilliam Shakespeareinto theSerbian language.[4]Kostić also wrote an introduction of Shakespeare's works toSerbian culture.[5]

Laza Kostić | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Lazar Kostić 12 February 1841 Kabol,Austrian Empire(modern-daySerbia) |

| Died | 27 November 1910(aged 69) Vienna,Austria-Hungary |

| Resting place | Sombor,Serbia |

| Pen name | Laza Kostić |

| Occupation | poet, dramatist, journalist |

| Language | Serbian |

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Education | University of Budapest |

| Period | 1868–1910 |

| Genre | romanticism |

| Notable works | Santa Maria della Salute Među javom i med snom |

| Spouse | 1 |

Biography

editLaza Kostić was born in 1841 inKovilj,Vojvodina—which was then part of theAustrian Empire—to a military family.[6]Kostić graduated from the Law School of theUniversity of Budapestand received aDoctor of Philosophyinjurisprudenceat the same university in 1866. A part of his thesis was about theDušan's Code.[7]After completing his studies, Kostić occupied several positions and was active in cultural and political life inNovi Sad,Belgrade,andMontenegro.He was one of the leaders ofUjedinjena omladina srpska(United Serb Youth)[8]and was elected a Serbian representative to the Hungarian parliament, thanks to his mentorSvetozar Miletić.[9]Because of his liberal and nationalistic views, Kostić had to leaveAustria-Hungary.He returned home after several years in Belgrade and Montenegro.

From 1869 to 1872, Kostić was the president of Novi Sad's Court House and was virtually the leader of his party in his county. He was a delegate in the clerico-secularSaboratSremski Karlovciseveral times. He served as Lord Mayor of Novi Sad twice and also twice asSajkasidelegate to the Parliament in Budapest.[8]

After Svetozar Miletić andJovan Jovanović Zmaj,Laza Kostić was the most active leader in Novi Sad; his politics were distinct from those of his associates but he was convinced his mission to save Serbia through art had been baulked byobscurantistcourtiers. In 1867, the Austrian Empire becameAustria-Hungaryand theKingdom of Hungarybecame one of two autonomous parts of the new state. This was followed by a policy ofHungarizationof the non-Hungarian nationalities, most notably promotion of the Hungarian-language and suppression of Romanian and Slavic languages, including Serbian. As the chief defender of the United Serbian Youth movement, Kostić was especially active in securing the repeal of some laws imposed on his and other nationalities in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. WhenMihailo Obrenović III, Prince of Serbia,was assassinated, the Austro-Hungarian authorities sought to falsely implicate Laza, his mentor Miletić, and other Serbian intellectuals in a murder plot.[10]Kostić was arrested and incarcerated but like the rest of them he was later released. In 1868, the new Prince of Serbia was the fourteen-year-oldMilan IVObrenović, who had fallen in love with Laza's most recent workMaksim Crnojević,which had been released that year.

Kostić moved to Belgrade, where he became a popular figure as a poet. Through Milan's influence, Kostić obtained the position of editor ofSrpsku nezavisnost(Serbian Independence), an influential political and literary magazine. Milan chose him to beJovan Ristić's principal assistant at the 1878Congress of Berlinand in 1880 Kostić was sent toSaint Petersburgas a member of the Serbian delegation.[9]Belgrade's opposition parties began taking issue with Kostić's writings; he had boasted of his power over the King in jest but had disdain to make influential friends at court so in 1883 King Milan ask him to leave Belgrade for a time. Despite his bizarreness, Kostić was ranked a great poet and writer. Soon after, he took up residence inCetinjeand became editor-in-chief of the official paper of theKingdom of MontenegroGlas Crnogoraca(The Montenegrin Voice),[11]where he met intellectualsSimo Matavulj,Pavel Rovinsky,andValtazar Bogišić.In 1890, Kostić moved toSomborwhere he married Julijana Palanački in September 1895 and spent the rest of his life there. In Sombor he wrote a book which describes his dreamsDnevnik snova(Diary of Dreams),[12]and the popular poemSanta Maria della Salute,which is considered the finest example of hislove poemsandelegies.[13][14][15]

Kostić has been following two lines in his work and research: theoretical mind cannot reach absolute, not having the richness of fascination and life necessary to its universality.[16]He was opposed to theanthropological philosophyofSvetozar Markovićand the views of revolutionist and materialistNikolay Chernyshevsky.[17]

He died on 27 November 1910 in Vienna.[1]

Verse and prose

editIn his poetry, Kostić often touched upon universal themes and human concerns, especially the relationships between man and God, society, and fellow humans. He contributed stylistic and linguistic innovations, experimenting freely, often at the expense of clarity. His work is closer to EuropeanRomanticismthan that of any other Serbian poet of his time. Kostić attempted unsuccessfully in numerous, incomplete theoretical essays to combine the elements of the native folk song with those of European Romanticism. The lack of success can be attributed to the advanced nature of his poetry, the ideas of his time, and his eccentricity.

Of Kostić's plays.Maksim Crnojević(1863) represents the first attempt to dramatize an epic poem.Pera Segedinac(1875) deals with the struggle of the Serbs for their rights in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his playGordana(1890) did not receive much praise.[18]

Kostić was a controversial personality; he was more celebrated than understood in his youth and became less popular in his old age, only achieving real fame after his death. Today, it is generally accepted that Kostić is the originator of modern Serbian poetry.[citation needed]

Translation of works in English

editAt the age of eighteen, in 1859, Kostić undertook the task of translating the works ofWilliam Shakespeare.[19]Kostić researched and published works on Shakespeare for around 50 years.[19]

The cultural ideals that motivated Kostić to translateRomeo and Julietinto Serbian were part of the Serbian literary revival that originated withDositej Obradovićin the eighteenth century. At the time, theatre emerged following the Serbian people's campaign for national independence in the late eighteenth century. During the 1850s and inter-war years, Kostić and his collaborator Andrejević made efforts to introduce Shakespeare to the Serbian public.

He tried to bring closer the Balkan cultures and theAntiquity,experimenting with the translation ofHomerinto the Serbian-epicdecametre.[19]He translated the works of many other foreign authors, notablyHeinrich Heine,Heinrich Dernburg,Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton'sThe Last Days of Pompeii,and Hungarian poetJózsef Kiss.

All Serbian intellectuals of the period believed the existence of their country was bound to the fate of their native tongue, then spoken widely throughout the two foreign empires. This premise provided for Kostić's translation ofRomeo and Juliet.The Serbian translation ofRichard IIIwas the joint effort of Kostić and his friend, the physician and authorJovan Andrejević-Joles.[20]Andrejević also participated in the founding of Novi Sad'sSerbian National Theatrein 1861. The year of the appearance ofRichard III(1864) in Novi Sad coincided with the 300-year anniversary of Shakespeare's birth; for that occasion, Kostić adapted two scenes fromRichard IIIusing theiambic versefor the first time.Richard IIIwas staged in Serbia and directed by Kostić himself. Later, he translatedHamletbut his work was met with criticism by notable literary criticBogdan Popović.[4][21]

Kostić's translation of the fourteenth stanza fromByron's Canto III[22]ofDon JuanexpressesByron's advice to the Greek insurgents:

Trust not for freedom to the Franks –

They have a king who buys and sells

In native swords, and native ranks

The only hope of courage dwells,

But Turkish force, and Latin Fraud

Would break your shield, however broad.

Personality and private life

editLaza Kostić may be characterized as an eccentric but had a spark of genius. He was the first to introduce iambic meter into dramatic poetry and the first translator of Shakespeare into Serbian. At a European authors' convention at the turn of the 20th century he tried to explain the relationship between the culture of Serbia and those of major Western European cultures.

Kostić was friends withLazar Dunđerski,the patriarch of one of the most important Serbian noble families in Austria-Hungary.[23]He was in love with JelenaLenkaDunđerski, Lazar's younger daughter,[23]who was 29 years his junior.[24]Although Lenka returned his love, Lazar Dunđerski did not approve of their relationship and would not allow them to marry.[24]He arranged a marriage between Kostić and Juliana Palanački.[24]Kostić attempted to arrange a marriage between Lenka and the Serbian-American scientistNikola Teslabut Tesla rejected the offer.[25]

Lenka died, probably from an infection, on her 25th birthday[26]but some authors believe she committed suicide.[12]After her death, Kostić wroteSanta Maria della Salute,one of his most important works[27][28]and what is said to be one of the most beautiful love poems written in Serbian language.[26][29][30]

Legacy

editLaza Kostić is included inThe 100 most prominent Serbs.Schools in Kovilj andNew Belgradeare named after him.[31]

Selected works

edit- Maksim Crnojević,drama (1868).

- Pera Segedinac,drama (1882).

- Gordana,drama (1890).

- Osnova lepote u svetu s osobenim obzirom na srpske narodne pesme,(1880).

- Kritički uvod u opštu filosofiju,(1884).

- O Jovanu Jovanoviću Zmaju (Zmajovi), njegovom pevanju, mišljenju i pisanju, i njegovom dobu,(1902).

- Među javom i med snom,poem.

- Santa Maria della Salute,poem.

- Treće stanje duše,essay[1]

- Čedo vilino,short story.

- Maharadža,short story.

- Mučenica,short story.

- Selected translations

References

edit- ^abcGacic, Svetlana."Laza Kostic".

- ^"Jedan od najznačajnijih književnika srpskog romantizma živeo je u Somboru, znate li o kome je reč? (FOTO/VIDEO)".www.srbijadanas.com(in Serbo-Croatian).Retrieved5 January2020.

- ^"Laza Kostić – Biografija – Bistrooki"(in Serbian).Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^ab"Laza Kostić – pionir u prevođenju Šekspira na srpski jezik".Blog prevodilačke agencije Libra | Prevodioci.co.rs(in Serbian). 8 August 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 8 November 2019.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"ЛАЗА КОСТИЋ ЈЕ ШЕКСПИРА УВЕО У СРПСКУ КУЛТУРУ ПРЕКО НОВОГ САДА".Културни центар Новог Сада(in Serbian). 26 December 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 18 November 2017.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"Културни магазин: Лаза Костић • Радио ~ Светигора ~".svetigora.com(in Serbian).Retrieved5 January2020.

- ^"Doktorska disertacija pesnika Laze Kostića 'De legibus serbicis Stephani Uros Dusan'".scindeks.ceon.rs.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^ab"Laza Kostić sklapao niti srpskog jedinstva".www.novosti.rs(in Serbian (Latin script)).Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^ab"ZELEN DOBOŠ DOBUJE, LAZA KOSTIĆ ROBUJE… – Ravnoplov".Retrieved5 January2020.

- ^"kreativna radionica balkan".www.krbalkan.rs.Retrieved5 January2020.

- ^Admin."Лаза Костић - велики песник, визионар и журналиста".Музеј Војводине(in Serbian).Retrieved5 January2020.

- ^ab"ОТКРИВАЛАЧКЕ СНОХВАТИЦЕ".Galaksija Nova(in Serbian). 20 April 2017.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^Scribd:Laza Kostić:AutobiografijaArchived5 November 2012 at theWayback Machine(Autobiography of Laza Kostić)(in Serbian)

- ^"Пројекат Растко: Dragan Stojanović: Između astralnog i sakralnog:" Santa Maria della Salute "Laze Kostića".www.rastko.rs.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"Korifej onirizma srpske romantičarske književnosti, Laza Kostić".scindeks.ceon.rs.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"Pesništvo i poetika Laze Kostića - jedan sintetičan pogled".scindeks.ceon.rs.Retrieved5 January2020.

- ^"Književnoteorijski i filosofski stavovi Laze Kostića".scindeks.ceon.rs.Retrieved5 January2020.

- ^"Kostićeve drame".Mingl.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^abc"Фонд Лаза Костић | О Лази Костићу".the-laza-kostic-fund.com.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"dr Jovan Andrejević Joles, prvi srpski anatom - život i delo".scindeks.ceon.rs.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^Ružić, Žarko."Sad nema tu trt – mrt!".Politika Online.Archivedfrom the original on 2 June 2017.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"Бајрон и Лаза Костић - ИСТОРИЈСКА БИБЛИОТЕКА".www.istorijskabiblioteka.com.Archived fromthe originalon 31 May 2019.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^ab"PRVA LAZINA PESMA O LENKI – Ravnoplov".Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^abc"Ljubavi srpskih pisaca: Laza Kostić".WANNABE MAGAZINE.10 March 2012.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"KAKO JE LAZA KOSTIĆ UDAVAO LENKU ZA NIKOLU TESLU – Ravnoplov".Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^ab"СНП: Академија посвећена Лазару Дунђерском и сећање на Ленку".Дневник(in Serbian).Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"Intertekstualnost Santa Maria della Salute u svjetlu književne kritike druge polovine XX vijeka".scindeks.ceon.rs.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"[Projekat Rastko] Antologija srpskog pesnistva".www.rastko.rs.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"SCIIntertekstualnost Santa Maria della Salute u svjetlu književne kritike druge polovine XX vijeka".scindeks.ceon.rs.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"Laza Kostić - Santa Maria della Salute".

- ^"Početak".www.lkostic.edu.rs.Retrieved5 January2020.

- Adapted from Serbian Wikipedia:Лаза Костић

- Translated and adapted fromJovan Skerlić'sIstorija Nove Srpske Književnosti(Belgrade, 1914, 1921), pages 319–325

External links

edit- Biography(Serbian)

- Selection of Works(Serbian)

- Poems(Serbian)

- Laza Kostic Fund(Serbian)

- Translated works by Laza Kostić