TheLocrian modeis the seventh mode of the major scale. It is either amusical modeor simply adiatonic scale.On the piano, it is the scale that starts with B and only uses the white keys from there on up to the next higher B. Its ascending form consists of the key note, then: Half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step.

History

editLocrianis the word used to describe an ancient Greek tribe that habited the three regions ofLocris.[1]Although the term occurs in several classical authors on music theory, includingCleonides(as an octave species) andAthenaeus(as an obsoleteharmonia), there is no warrant for the modern use of Locrian as equivalent toGlarean'shyperaeolian mode, in either classical, Renaissance, or later phases of modal theory through the 18th century, or modern scholarship on ancient Greek musical theory and practice.[2][3]

The name first came into use in modal chant theory after the 18th century,[2]whenLocrianwas used to describe the newly-numbered mode 11, with its final on B,ambitusfrom that note to the octave above, and with semitones therefore between the first and second, and between the fourth and fifth degrees. Itsreciting tone(or tenor) is G, itsmediantD, and it has twoparticipants:E and F.[4]Thefinal,as its name implies, is the tone on which the chant eventually settles, and corresponds to the tonic in tonal music. The reciting tone is the tone around which the melody principally centers,[5]the termmediantis named from its position between the final tone and the reciting tone, and the participant is an auxiliary note, generally adjacent to the mediant inauthentic modesand, in theplagalforms, coincident with the reciting tone of the corresponding authentic mode.[6]

Modern Locrian

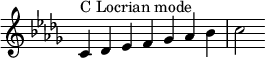

editIn modern practice, the Locrian may be considered to be one of the modernminor scales:Thenatural minorwith the step beforesecond[disambiguation needed]and thefifthscale degrees reduced from a tone to asemitone.The Locrian mode may also be considered to be a scale beginning on the seventh scale degree of anyIonian,or modern naturalmajor scale.The Locrian mode has the formula:

- 1,♭2,♭3, 4,♭5,♭6,♭7

The chord progression for Locrian starting on B is Bdim 5,CMaj,Dmin,Emin,FMaj,GMaj,Amin.

Itstonic chordis adiminished triad(Bdim= Bdim 5

min 3=BDF,in the Locrian mode using the white-key diatonic scale with starting note B, corresponding to a C major scale starting on its 7th tone). This mode's diminished fifth and theLydian mode's augmented fourth are the only modes that contain atritoneas a note in their modal scale.

Overview

editThe Locrian mode is the only modern diatonic mode in which thetonic triadis adiminished chord(flattened fifth), which is considered verydissonant.This is because the interval between therootand fifth of the chord is adiminished fifth.For example, the tonic triad of B Locrian is made from the notes B, D, F. The root is B and thedim5th is F. The diminished-fifth interval between them is the cause for the chord's striking dissonance.[citation needed]

The name "Locrian" is borrowed from music theory ofancient Greece.However, what is now called theLocrian modewas what the Greeks called thediatonicMixolydiantonos.The Greeks used the term "Locrian" as an alternative name for their "Hypodorian",or" common "tonos, with a scale running frommesetonete hyperbolaion,which in its diatonic genus corresponds to the modernAeolian mode.[7]

In his reform of modal theory,[8]Glareannamed this division of the octave "hyperaeolian" and printed some musical examples (a three-part polyphonic example specially commissioned from his friendSixtus Dietrich,and the Christe from a mass byde la Rue), though he did not accept hyperaeolian as one of his twelve modes.[9]The use of the term "Locrian" as equivalent to Glarean'shyperaeolianor the ancient Greek (diatonic)mixolydian,however, has no authority before the 19th century.[2]

Use

editThis sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(January 2023) |

Used in orchestral music

editThere are brief passages that have been, or may be, regarded as being in the Locrian mode in orchestral works by

- Sergei Rachmaninoff(Prelude in B minor, op. 32, no. 10),[10]

- Paul Hindemith(Ludus Tonalis),[10]

- Jean Sibelius(Symphony No. 4 in A minor, op. 63).[10]

- Claude Debussy'sJeuxhas three extended passages in the Locrian mode.[11]

- Paul Hindemith's "Turandot Scherzo", the theme of the second movement ofSymphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber(1943) alternates sections inmixolydianand Locrian modes, ending in Locrian.[12]

- Benjamin Brittenused the Locrian mode for "In Freezing Winter's Night", the ninth song inA Ceremony of Carols.

Use in folk and popular music

editThe Locrian mode is almost never used in folk or popular music:

- "In practical terms it should be said that few rock songs that use modes such as the Phrygian, Lydian, or Locrian actually maintain a harmony rigorously fixed on them. What usually happens is that the scale is harmonized in [chords with perfect] fifths and the riffs are then played [over] those [chords]."[13]

Among the very few instances of folk & popular music in the Locrian mode:

- The Locrian is used inMiddle Eastern musicasmaqam Lami.[citation needed][further explanation needed]

- Slipknot's track "Everything Ends"uses an A Locrian scale with the fourth note sometimes flattened.[13]

- English folk musicianJohn Kirkpatrick's song "Dust to Dust" was written in the Locrian mode,[14]backed by hisconcertina.The Locrian mode is not at all traditional in English music, but was used by Kirkpatrick as a musical innovation.[15]

- Björk's "Army of Me"is dominated by a heavy bassline in C Locrian.[16]

- The modernpop song"Gliese 710" fromKing Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard's 2022 albumIce, Death, Planets, Lungs, Mushrooms and Lavais in Locrian, following the album's theme of basing each song around one of the Greek modes.[17]

References

edit- ^"Locrian".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^abcPowers, Harold S. (2001a). "Locrian". InSadie, Stanley;Tyrrell, John(eds.).The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians(2nd ed.). London, UK: Macmillan Publishers. p. 158.

- ^Hiley, David(2002). "Mode". In Latham, Alison (ed.).The Oxford Companion to Music.Oxford, UK / New York, NY: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-866212-9.OCLC59376677.

- ^Rockstro, William Smyth (1880). "Locrian mode". InGrove, George, D.C.L.(ed.).A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450–1880), by eminent writers, English and foreign.Vol. 2. London, UK: Macmillan and Co. p. 158.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^Smith, Charlotte (1989).A Manual of Sixteenth-Century Contrapuntal Style.Newark, NJ / London, UK: University of Delaware Press / Associated University Presses. p.14.ISBN978-0-87413-327-1.

- ^Powers, Harold S. (2001b). "Modes, the ecclesiastical". InSadie, Stanley;Tyrrell, John(eds.).The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians(2nd ed.). London, UK: Macmillan Publishers. pp. 340–343,esp. p. 342.

- ^Mathiesen, T.J.(2001). "Greece, §1: Ancient; §6: Music Theory". InSadie, Stanley;Tyrrell, John(eds.).The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians(2nd ed.). London, UK: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^Glarean, H.(1547).Dodecachordon.

- ^Powers, Harold S. (2001c). "Hyperaeolian". InSadie, Stanley;Tyrrell, John(eds.).The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians(2nd ed.). London, UK: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^abcPersichetti, Vincent (1961).Twentieth Century Harmony.New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 42.

- ^Larín, Eduardo (Spring–Summer 2005)." " Waves "in Debussy'sJeux d'eau ".Ex Tempore.Vol. 12, no. 2 – via ex-tempore.org.

- ^Anderson, Gene (1996). The triumph of timelessness over time in Hindemith's "Turandot Scherzo" fromSymphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber.College Music Symposium. Vol. 36. pp. 1–15, citation p 3.

- ^abRooksby, Rikky (2010).Riffs: How to create and play great guitar riffs.Backbeat. p.121.ISBN9781476855486– via Google books.

- ^Boden, Jon(21 April 2012).""Dust to Dust"".A Folk Song a Day (afolksongaday.com).Archived fromthe originalon 3 October 2012.

- ^Kirkpatrick, John(Summer 2000)."The art of writing songs".English Dance & Song.62(2): 27.ISSN0013-8231.EFDSS55987.Retrieved23 October2020.

- ^Hein, Ethan (17 November 2015)."Musical simples: Army Of Me".The Ethan Hein Blog.Retrieved5 November2020.

- ^Anderson, Carys (7 September 2022)."King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard announce three albums dropping in October, share" Ice V ": Stream".Consequence (consequence.net)(music review).Retrieved2022-10-13.

Further reading

edit- Bárdos, Lajos (December 1976). "Egy 'szomorú' hangnem: Kodály zenéje és a lokrikum".Magyar zene: Zenetudományi folyóirat.17(4): 339–387.

- Hewitt, Michael (2013).Musical Scales of the World.The Note Tree.ISBN978-0957547001.

- Nichols, Roger; Smith, Richard Langham (1989).Claude Debussy,Pelléas et Mélisande.Cambridge Opera Handbooks. Cambridge, UK / New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-31446-6.

- Rahn, Jay (Fall 1978). "Constructs for modality, ca. 1300–1550".Canadian Association of University Schools of Music Journal / Association Canadienne des Écoles Universitaires de Musique Journal.8(2): 5–39.

- Rowold, Helge (April–June 1999). "'To achieve perfect clarity of expression, that is my aim': Zum Verhältnis von Tradition und Neuerung in Benjamin Britten'sWar Requiem".Die Musikforschung.52(2): 212–219.doi:10.52412/mf.1999.H2.889.

- Smith, Richard Langham (1992). "Pelléas et Mélisande". InSadie, Stanley(ed.).The New Grove Dictionary of Opera.Grove's Dictionaries of Music.London, UK / New York, NY: Macmillan Press.ISBN0-333-48552-1(UK)ISBN0-935859-92-6(US)

External links

edit- "Locrian mode for guitar".GOSK.com.