Michael X(17 August 1933 – 16 May 1975),[1]bornMichael de Freitas,was aTrinidad and Tobago-born self-styledblackrevolutionary,convicted murderer, andcivil rightsactivistin 1960sLondon.He was also known asMichael Abdul MalikandAbdul Malik.Convicted ofmurderin 1972, Michael X was executed byhangingin 1975 inPort of Spain's Royal Gaol.

Michael X | |

|---|---|

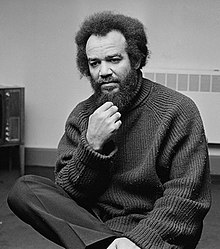

Michael X,c. 1970 | |

| Born | Michael de Freitas 17 August 1933 |

| Died | 16 May 1975(aged 41) Port of Spain Royal Gaol,Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Other names | Michael Abdul Malik Abdul Malik |

| Occupation | Activist |

| Movement | Black Power Movement |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

Biography

editMichael de Freitas was born inBelmont, Port of Spain,Trinidad and Tobago, to an "Obeah-practising black woman from Barbados and an absent Portuguese father fromSt Kitts".[2]Encouraged by his mother topass for white,"Red Mike" was a headstrong youth and was expelled from school at the age of 14.[2]In 1957, he emigrated to theUnited Kingdom,where he settled in London and worked as an enforcer and frontman forPeter Rachman,the notoriousslum landlord.[3]He professed to dislike the role, but it paid for his lifestyle. Appearing to look for a way out, he became involved in the radical politics and groups active in and aroundNotting Hill.[4]

By the mid-1960s, he had become known as Michael X. "Michael X" became a well-known exponent ofBlack Powerin London. Writing inThe Observerin 1965, Colin McGlashan called him the "authentic voice of black bitterness."[5]

In 1965, under the name Abdul Malik, he founded theRacial Adjustment Action Society(RAAS).[6]

In 1967, he was involved with thecounterculture/hippie organisation theLondon Free School(LFS) through his contact withJohn "Hoppy" Hopkins,which both helped widen the reach of the group, at least in the Notting Hill area, and create problems with local police who disliked his involvement. Michael and the LFS were instrumental in organising the first outdoorNotting Hill Carnivallater that year.[7]

Later that year, he became the first non-white person to be charged and imprisoned under the UK'sRace Relations Act,which was designed to protect Britain's Black andAsianpopulations fromdiscrimination.[8]He was sentenced to 12 months in prison, having been arrested on the accusation of using words likely to stir up hatred "against a section of the public in Great Britain distinguished by colour".[9]This was after his speech at an event inReadingwhen he said, referring to theNotting Hill race riots:"In 1958, I saw white savages kicking black women in the streets and black brothers running away. If you ever see a white laying hands on a black woman, kill him immediately."[10][11]He also said "white men have no soul".[12]

In 1969, he became the self-appointed leader of a Black PowercommuneonHolloway Road,North London,called the "Black House". The commune was financed by a young millionaire benefactor, Nigel Samuel. Michael X said, "They've made me the archbishop of violence in this country. But that 'get a gun' rhetoric is over. We're talking of really building things in the community needed by people in the community. We're keeping a sane approach."[13]John LennonandYoko Onodonated a bag of their hair to be auctioned for the benefit of the Black House.[14]

In what the media called "the slave collar affair", businessman Marvin Brown was enticed to The Black House, viciously attacked, and made to wear a spiked "slave" collar around his neck as Michael X and others threatened him in order toextortmoney.[15]The Black House closed in the autumn of 1970. The two men found guilty of assaulting Marvin Brown were imprisoned for 18 months.[16]

The Black House burned down in mysterious circumstances, and soon Michael X and four colleagues were arrested for extortion. His bail was paid by John Lennon in January 1971.[17]

In February 1971, Michael X fled to his native Trinidad and Tobago, where he started an agricultural commune devoted toBlack empowerment16 miles (26 km) east of the capital,Port of Spain."The only politics I ever understand is the politics of revolution," he told theTrinidad Express."The politics of change, the politics of a completely new system."[5]He began another commune, also called the Black House, which, in February 1972, also burned down.

Murder trial

editPolice who had come to the commune to investigate the fire discovered the bodies of Joseph Skerritt andGale Benson,members of the commune. They had been hacked to death and separately buried in shallow graves. Benson, who had been going under the name Hale Kimga, was the daughter ofConservativeMPLeonard F. Plugge.She had met Michael X through her relationship with his associateHakim Jamal.

At the time of the discovery, Michael X and his family were in Guyana by invitation of the Guyanese Prime MinisterForbes Burnham.He was then captured in Guyana and charged with the murder of Skerritt and Benson, but was never tried for the latter crime. The trial was held in Trinidad; it was alleged that the killings were carried out by his followers Stanley Abbott and Edward Chadee.[18]A witness at his trial said that Skerritt was a member of Michael X's "Black Liberation Army"and had been killed by him because he refused to obey orders to attack a local police station. Michael X was found guilty and sentenced to death.[18][19]

The Save Malik Committee, whose members includedAngela Davis,Dick Gregory,Kate Millettand others, including the well-known, self-described "radical lawyer"[20]William Kunstler,who was paid byJohn Lennon,[17]pleaded for clemency, but Michael X was hanged in 1975.[19][18]Stanley Abbott was hanged for the murder of Gale Benson in 1979, while Edward Chadee's death sentence was reduced to life in prison.[21]

Legacy

editUnder the name Michael Abdul Malik, Michael X was the author of the autobiographyFrom Michael de Freitas to Michael X(André Deutsch,1968), which was ghost-written byJohn Stevenson.[22]Michael X also left behind fragments of a novel about a romantic black hero who wins the abject admiration of the narrator, a young woman named Lena Boyd-Richardson. The novel was never completed.[5][23]

Cultural references

editMichael X is the subject of the essay "Michael X and the Black Power Killings in Trinidad" byV. S. Naipaul,collected inThe Return of Eva Perón and the Killings in Trinidad(1980), and is also believed to be the model for the fictional character Jimmy Ahmed in Naipaul's 1975 novelGuerrillas.

Michael X is a character inThe Bank Job(2008), a dramatisation ofa real-life bank robberyin 1971. The film claims that Michael X was in possession of indecent photographs ofPrincess Margaretand used them to avoid criminal prosecution by threatening to publish them; according to the movie plot, X killed Gale Benson because she was a British Secret Services agent and revealed where he kept the blackmail material. He was played byPeter de Jersey.[24]

Michael X and his trial are the subject of a chapter inGeoffrey Robertson's legal memoirThe Justice Game(1998).

Documentary film,Who Needs a Heart(1991), is inspired by Michael X.John Akomfrahis the director.[25]

Michael X plays a part inMake Believe: A True Story(1993), a memoir byDiana Athill.[26]

Michael Xis the eponymous title of a play, by the writerVanessa Walters,that takes the form of a 1960s Black Power rally and was performed atThe Tabernacle Theatre,Powis Square,London W11 (Notting Hill), in November 2008.

Michael X (played byAdrian Lester) is portrayed in a scene oppositeJimi Hendrixin the 2013 filmAll Is By My Side,based on Hendrix's early years in the music industry.

In 1966,Muhammad Aligave his bloodied boxing shorts that he wore when he foughtHenry Cooperto Michael Abdul Malik, who is referred to as a black militant from Trinidad inThe Greatest: My Own Story(1975) by Muhammad Ali withRichard Durham.

Michael X is a subject in the 2021Adam Curtisdocumentary seriesCan't Get You Out of My Head.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^Alexander, Camille (2016)."Michael X".African American Studies Center.Oxford African American Studies Center.doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.74562.ISBN978-0-19-530173-1.

- ^abBusby, Margaret,"Notting Hill to death row"(review ofMichael X: A Life In Black And White,by John Williams),The Independent,8 August 2008.

- ^Fountain, Nigel,Underground: The London Alternative Press, 1966–74,London: Taylor & Francis, 1988, p. 8.ISBN9780415007283

- ^Hall, Stuart(2017).Familiar Stranger.Penguin.ISBN978-0-141-98475-9.

- ^abcDidion, Joan(12 June 1980),"Without Regret or Hope",The New York Review of Books.

- ^Werbner, Pnina (1991).Black and Ethnic Leaderships in Britain: The Cultural Dimensions of Political Action.London: Routledge. p. 29.ISBN9780415041669.

- ^Miles, Barry(2010),London Calling: A Countercultural History of London Since 1945,pp. 187–90.

- ^Eds (10 November 1967), "Black Muslim Gets One Year in Britain".The New York Times.

- ^"Retrial ordered for black activist Michael X – archive 1967".The Guardian.19 October 2018.

- ^Bunce, Robin; Paul Field (October 2017)."Michael X and the British war on black power".History Extra.BBC.Retrieved17 November2021.

- ^Eds (30 September 1967), "Michael X On Trial For Race Hate Charges",The Times.

- ^Gelber, Katharine,Speaking Back: the free speech versus hate speech debate,John Benjamins, 2002, p. 105.ISBN9789027297709

- ^Eds (29 January 1970), "London Getting a Black Cultural Leader".The New York Times.

- ^Cavett, Dick(11 September 1971).The Dick Cavett Show(Television).Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2021.Retrieved21 December2015.

- ^Naughton, Philippe (23 June 1970)."Man In Michael X Centre led in 'slave collar'".The Times.London. Archived fromthe originalon 6 October 2008.Retrieved13 November2008.

- ^Naughton, Philippe (14 July 1971)."Two found guilty in Black Power case".The Times.London. Archived fromthe originalon 6 October 2008.Retrieved13 November2008.

- ^abHarry, Bill,The John Lennon Encyclopedia,Virgin Books, 2001.

- ^abc"Militant Is Hanged by Trinidad After Long Fight for Clemency".The New York Times.17 May 1975.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved11 February2023.

- ^ab"'MICHAEL X' DOOMED IN TRINIDAD MURDER ".The New York Times.22 August 1972.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved31 July2022.

- ^Kunstler, William Moses; Isenberg, Sheila (1994).My Life as a Radical Lawyer.Carol Pub.ISBN9781559722650.

- ^Wallis, Keith (2008).And the world listened: The biography of Captain Leonard F. Plugge - A pioneer of commercial radio.Devon: Kelly Publications. p. 189.ISBN978-1-903053-23-2.OCLC1313866274.

- ^"Michael X and the Black House of Holloway Road".Darkest London.17 June 2013.Retrieved17 November2021.

- ^Barfoot, C. C., and Theo d' Haen,Shades of Empire in Colonial and Post-colonial Literatures: In Colonial and Post-colonial Literatures,Rodopi, 1993, p. 241.ISBN9789051833645

- ^The Bank Job: Production Informationwww.lionsgatefilms.co.ukArchived2 February 2008 at theWayback Machine

- ^"BFI Screenonline: Who Needs A Heart (1991)".www.screenonline.org.uk.Retrieved30 May2022.

- ^Neville, Jill(23 January 1993)."BOOK REVIEW / Tripping out with a con artist: 'Make Believe: A True Story' - Diana Athill: Sinclair-Stevenson, 13.99 pounds".The Independent.

Further reading

edit- Malik, Michael Abdul.From Michael de Freitas to Michael X(London: André Deutsch, 1968).

- Levy, William, and Michell, John (editors).Souvenir Programme for the Official Lynching of Michael Abdul Malik with Poems, Stories, Sayings by the Condemned(privately published: Cambridge, England, 1973).

- Humphry, Derek.False Messiah - The Story of Michael X(London: Hart-Davis, MacGibbon Ltd, 1977).

- Naipaul, V. S. "Michael X and the Black Power Killings in Trinidad", in:The Return of Eva Perón and the Killings in Trinidad(London: André Deutsch, 1980).

- Sharp, James.The Life and Death of Michael X(Uni Books, 1981).

- Athill, Diane.Make Believe: A True Story(London: Granta Books, 1993).

- Williams, John.Michael X: A Life in Black and White(London: Century, 2008).