Molybdenum disulfide(or moly) is aninorganic compoundcomposed ofmolybdenumandsulfur.Itschemical formulaisMoS2.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Molybdenum disulfide

| |

| Other names

Molybdenum(IV) sulfide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.877 |

PubChemCID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard(EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| MoS2 | |

| Molar mass | 160.07g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | black/lead-gray solid |

| Density | 5.06 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 2,375 °C (4,307 °F; 2,648 K)[4] |

| insoluble[1] | |

| Solubility | decomposed byaqua regia,hotsulfuric acid,nitric acid insoluble in dilute acids |

| Band gap | 1.23 eV (indirect, 3R or 2H bulk)[2] ~1.8 eV (direct, monolayer)[3] |

| Structure | |

| hP6,P6 3/mmc,No. 194 (2H) | |

a= 0.3161 nm (2H), 0.3163 nm (3R),c= 1.2295 nm (2H), 1.837 (3R)

| |

| Trigonal prismatic(MoIV) Pyramidal (S2−) | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy(S⦵298) |

62.63 J/(mol·K) |

Std enthalpy of

formation(ΔfH⦵298) |

−235.10 kJ/mol |

Gibbs free energy(ΔfG⦵)

|

−225.89 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet(SDS) | External MSDS |

| Related compounds | |

Otheranions

|

Molybdenum(IV) oxide Molybdenum diselenide Molybdenum ditelluride |

Othercations

|

Tungsten disulfide |

Relatedlubricants

|

Graphite |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in theirstandard state(at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

The compound is classified as atransition metal dichalcogenide.It is a silvery black solid that occurs as the mineralmolybdenite,the principal ore for molybdenum.[6]MoS2is relatively unreactive. It is unaffected by diluteacidsandoxygen.In appearance and feel, molybdenum disulfide is similar tographite.It is widely used as adry lubricantbecause of its lowfrictionand robustness. BulkMoS2is adiamagnetic,indirect bandgapsemiconductor similar tosilicon,with a bandgap of 1.23 eV.[2]

Production

editMoS2is naturally found as eithermolybdenite,a crystalline mineral, or jordisite, a rare low temperature form of molybdenite.[7]Molybdenite ore is processed byflotationto give relatively pureMoS2.The main contaminant is carbon.MoS2also arises by thermal treatment of virtually all molybdenum compounds withhydrogen sulfideor elemental sulfur and can be produced by metathesis reactions frommolybdenum pentachloride.[8]

Structure and physical properties

editCrystalline phases

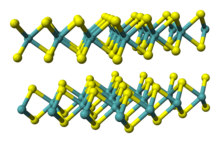

editAll forms ofMoS2have a layered structure, in which a plane of molybdenum atoms is sandwiched by planes of sulfide ions. These three strata form a monolayer ofMoS2.BulkMoS2consists of stacked monolayers, which are held together by weakvan der Waals interactions.

CrystallineMoS2exists in one of two phases, 2H-MoS2and 3R-MoS2,where the "H" and the "R" indicate hexagonal and rhombohedral symmetry, respectively. In both of these structures, each molybdenum atom exists at the center of atrigonal prismaticcoordination sphereand is covalently bonded to six sulfide ions. Each sulfur atom has pyramidal coordination and is bonded to three molybdenum atoms. Both the 2H- and 3R-phases are semiconducting.[10]

A third, metastable crystalline phase known as 1T-MoS2was discovered by intercalating 2H-MoS2withalkali metals.[11]This phase has trigonal symmetry and is metallic. The 1T-phase can be stabilized through doping with electron donors such asrhenium,[12]or converted back to the 2H-phase by microwave radiation.[13]The 2H/1T-phase transition can be controlled via the incorporation of Svacancies.[14]

Allotropes

editNanotube-like andbuckyball-like molecules composed ofMoS2are known.[15]

ExfoliatedMoS2flakes

editWhile bulkMoS2in the 2H-phase is known to be an indirect-band gap semiconductor, monolayerMoS2has a direct band gap. The layer-dependent optoelectronic properties ofMoS2have promoted much research in 2-dimensionalMoS2-based devices. 2DMoS2can be produced by exfoliating bulk crystals to produce single-layer to few-layer flakes either through a dry, micromechanical process or through solution processing.

Micromechanical exfoliation, also pragmatically called "Scotch-tape exfoliation",involves using an adhesive material to repeatedly peel apart a layered crystal by overcoming the van der Waals forces. The crystal flakes can then be transferred from the adhesive film to a substrate. This facile method was first used byKonstantin NovoselovandAndre Geimto obtain graphene from graphite crystals. However, it can not be employed for a uniform 1-D layers because of weaker adhesion ofMoS2to the substrate (either Si, glass or quartz); the aforementioned scheme is good for graphene only.[16]While Scotch tape is generally used as the adhesive tape,PDMSstamps can also satisfactorily cleaveMoS2if it is important to avoid contaminating the flakes with residual adhesive.[17]

Liquid-phase exfoliation can also be used to produce monolayer to multi-layerMoS2in solution. A few methods include lithiumintercalation[18]to delaminate the layers andsonicationin a high-surface tension solvent.[19][20]

Mechanical properties

editMoS2excels as a lubricating material (see below) due to its layered structure and lowcoefficient of friction.Interlayer sliding dissipates energy when a shear stress is applied to the material. Extensive work has been performed to characterize the coefficient of friction and shear strength ofMoS2in various atmospheres.[21]Theshear strengthofMoS2increases as the coefficient of friction increases. This property is calledsuperlubricity.At ambient conditions, the coefficient of friction forMoS2was determined to be 0.150, with a corresponding estimated shear strength of 56.0 MPa (megapascals).[21]Direct methods of measuring the shear strength indicate that the value is closer to 25.3 MPa.[22]

The wear resistance ofMoS2in lubricating applications can be increased bydopingMoS2withCr.Microindentation experiments onnanopillarsof Cr-dopedMoS2found that the yield strength increased from an average of 821 MPa for pureMoS2(at 0% Cr) to 1017 MPa at 50% Cr.[23]The increase in yield strength is accompanied by a change in the failure mode of the material. While the pureMoS2nanopillar fails through a plastic bending mechanism, brittle fracture modes become apparent as the material is loaded with increasing amounts of dopant.[23]

The widely used method of micromechanical exfoliation has been carefully studied inMoS2to understand the mechanism of delamination in few-layer to multi-layer flakes. The exact mechanism of cleavage was found to be layer dependent. Flakes thinner than 5 layers undergo homogenous bending and rippling, while flakes around 10 layers thick delaminated through interlayer sliding. Flakes with more than 20 layers exhibited a kinking mechanism during micromechanical cleavage. The cleavage of these flakes was also determined to be reversible due to the nature of van der Waals bonding.[24]

In recent years,MoS2has been utilized in flexible electronic applications, promoting more investigation into the elastic properties of this material. Nanoscopic bending tests usingAFMcantilever tips were performed on micromechanically exfoliatedMoS2flakes that were deposited on a holey substrate.[17][25]The yield strength of monolayer flakes was 270 GPa,[25]while the thicker flakes were also stiffer, with a yield strength of 330 GPa.[17]Molecular dynamic simulations found the in-plane yield strength ofMoS2to be 229 GPa, which matches the experimental results within error.[26]

Bertolazzi and coworkers also characterized the failure modes of the suspended monolayer flakes. The strain at failure ranges from 6 to 11%. The average yield strength of monolayerMoS2is 23 GPa, which is close to the theoretical fracture strength for defect-freeMoS2.[25]

The band structure ofMoS2is sensitive to strain.[27][28][29]

Chemical reactions

editMolybdenum disulfide is stable in air and attacked only by aggressivereagents.It reacts with oxygen upon heating formingmolybdenum trioxide:

- 2 MoS2+ 7 O2→ 2 MoO3+ 4 SO2

Chlorineattacks molybdenum disulfide at elevated temperatures to formmolybdenum pentachloride:

- 2 MoS2+ 7 Cl2→ 2 MoCl5+ 2 S2Cl2

Intercalation reactions

editMolybdenum disulfide is a host for formation ofintercalation compounds.This behavior is relevant to its use as a cathode material in batteries.[30][31]One example is a lithiated material,LixMoS2.[32]Withbutyl lithium,the product isLiMoS2.[6]

Applications

editLubricant

editDue to weakvan der Waalsinteractions between the sheets of sulfide atoms,MoS2has a lowcoefficient of friction.MoS2in particle sizes in the range of 1–100 μm is a commondry lubricant.[34]Few alternatives exist that confer high lubricity and stability at up to 350 °C in oxidizing environments. Sliding friction tests ofMoS2using apin on disc testerat low loads (0.1–2 N) give friction coefficient values of <0.1.[35][36]

MoS2is often a component of blends and composites that require low friction. For example, it is added to graphite to improve sticking.[33]A variety ofoilsandgreasesare used, because they retain their lubricity even in cases of almost complete oil loss, thus finding a use in critical applications such asaircraft engines.When added toplastics,MoS2forms acompositewith improved strength as well as reduced friction. Polymers that may be filled withMoS2includenylon(trade nameNylatron),TeflonandVespel.Self-lubricating composite coatings for high-temperature applications consist of molybdenum disulfide andtitanium nitride,usingchemical vapor deposition.

Examples of applications ofMoS2-based lubricants includetwo-stroke engines(such as motorcycle engines), bicyclecoaster brakes,automotiveCVanduniversal joints,ski waxes[37]andbullets.[38]

Other layered inorganic materials that exhibit lubricating properties (collectively known assolid lubricants(or dry lubricants)) includes graphite, which requires volatile additives and hexagonalboron nitride.[39]

Catalysis

editMoS2is employed as a cocatalystfor desulfurization inpetrochemistry,for example,hydrodesulfurization.The effectiveness of theMoS2catalysts is enhanced bydopingwith small amounts ofcobaltornickel.The intimate mixture of these sulfides issupportedonalumina.Such catalysts are generated in situ by treating molybdate/cobalt or nickel-impregnated alumina withH

2Sor an equivalent reagent. Catalysis does not occur at the regular sheet-like regions of the crystallites, but instead at the edge of these planes.[40]

MoS2finds use as ahydrogenationcatalystfororganic synthesis.[41]It is derived from a commontransition metal,rather thangroup 10metal as are many alternatives,MoS2is chosen when catalyst price or resistance to sulfurpoisoningare of primary concern.MoS2is effective for the hydrogenation ofnitro compoundstoaminesand can be used to producesecondaryamines viareductive amination.[42]The catalyst can also effecthydrogenolysisoforganosulfur compounds,aldehydes,ketones,phenolsandcarboxylic acidsto their respectivealkanes.[41]The catalyst suffers from rather low activity however, often requiring hydrogenpressuresabove 95atmand temperatures above 185 °C.

Research

editMoS2plays an important role incondensed matter physicsresearch.[43]

Hydrogen evolution

editMoS2and related molybdenum sulfides are efficient catalysts forhydrogen evolution,including theelectrolysis of water;[44][45]thus, are possibly useful to produce hydrogen for use infuel cells.[46]

Oxygen reduction and evolution

editMoS2@Fe-N-C core/shell[47]nanosphere with atomic Fe-doped surface and interface (MoS2/Fe-N-C) can be used as a used an electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and evolution reactions (ORR and OER) bifunctionally because of reduced energy barrier due to Fe-N4dopants and unique nature ofMoS2/Fe-N-C interface.

Microelectronics

editAs ingraphene,the layered structures ofMoS2and othertransition metaldichalcogenidesexhibit electronic and optical properties[48]that can differ from those in bulk.[49]BulkMoS2has an indirect band gap of 1.2 eV,[50][51]whileMoS2monolayershave a direct 1.8 eVelectronic bandgap,[52]supporting switchable transistors[53]andphotodetectors.[54][49][55]

MoS2nanoflakes can be used for solution-processed fabrication of layeredmemristiveand memcapacitive devices through engineering aMoOx/MoS2heterostructure sandwiched between silver electrodes.[56]MoS2-basedmemristorsare mechanically flexible, optically transparent and can be produced at low cost.

The sensitivity of a graphenefield-effect transistor(FET)biosensoris fundamentally restricted by the zero band gap of graphene, which results in increased leakage and reduced sensitivity. In digital electronics, transistors control current flow throughout an integrated circuit and allow for amplification and switching. In biosensing, the physical gate is removed and the binding between embedded receptor molecules and the charged target biomolecules to which they are exposed modulates the current.[57]

MoS2has been investigated as a component of flexible circuits.[58][59]

In 2017, a 115-transistor, 1-bitmicroprocessorimplementation was fabricated using two-dimensionalMoS2.[60]

MoS2has been used to create 2D 2-terminalmemristorsand 3-terminalmemtransistors.[61]

Valleytronics

editDue to the lack of spatial inversion symmetry, odd-layer MoS2 is a promising material forvalleytronicsbecause both the CBM and VBM have two energy-degenerate valleys at the corners of the first Brillouin zone, providing an exciting opportunity to store the information of 0s and 1s at different discrete values of the crystal momentum. TheBerry curvatureis even under spatial inversion (P) and odd under time reversal (T), the valley Hall effect cannot survive when both P and T symmetries are present. To excite valley Hall effect in specific valleys, circularly polarized lights were used for breaking the T symmetry in atomically thin transition-metal dichalcogenides.[62]In monolayerMoS2,the T and mirror symmetries lock the spin and valley indices of the sub-bands split by the spin-orbit couplings, both of which are flipped under T; the spin conservation suppresses the inter-valley scattering. Therefore, monolayer MoS2 have been deemed an ideal platform for realizing intrinsic valley Hall effect without extrinsic symmetry breaking.[63]

Photonics and photovoltaics

editMoS2also possesses mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, and can emit light, opening possible applications such as photodetectors.[64]MoS2has been investigated as a component of photoelectrochemical (e.g. for photocatalytic hydrogen production) applications and for microelectronics applications.[53]

Superconductivity of monolayers

editUnder an electric fieldMoS2monolayers have been found to superconduct at temperatures below 9.4 K.[65]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^abHaynes, William M., ed. (2011).CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics(92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL:CRC Press.p. 4.76.ISBN1-4398-5511-0.

- ^abKobayashi, K.; Yamauchi, J. (1995). "Electronic structure and scanning-tunneling-microscopy image of molybdenum dichalcogenide surfaces".Physical Review B.51(23): 17085–17095.Bibcode:1995PhRvB..5117085K.doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.51.17085.PMID9978722.

- ^Yun, Won Seok; Han, S. W.; Hong, Soon Cheol; Kim, In Gee; Lee, J. D. (2012). "Thickness and strain effects on electronic structures of transition metal dichalcogenides: 2H-MX2semiconductors (M= Mo, W;X= S, Se, Te) ".Physical Review B.85(3): 033305.Bibcode:2012PhRvB..85c3305Y.doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.85.033305.

- ^"Molybdenum Disulfide".PubChem.RetrievedAugust 31,2018.

- ^Schönfeld, B.; Huang, J. J.; Moss, S. C. (1983)."Anisotropic mean-square displacements (MSD) in single-crystals of 2H- and 3R-MoS2".Acta Crystallographica Section B.39(4): 404–407.Bibcode:1983AcCrB..39..404S.doi:10.1107/S0108768183002645.

- ^abSebenik, Roger F.et al.(2005) "Molybdenum and Molybdenum Compounds",Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology.Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_655

- ^"Jordisite".www.mindat.org.

- ^Murphy, Donald W.; Interrante, Leonard V.; Kaner; Mansuktto (1995). "Metathetical Precursor Route to Molybdenum Disulfide".Inorganic Syntheses.Vol. 30. pp. 33–37.doi:10.1002/9780470132616.ch8.ISBN9780470132616.

- ^Hong, J.; Hu, Z.; Probert, M.; Li, K.; Lv, D.; Yang, X.; Gu, L.; Mao, N.; Feng, Q.; Xie, L.; Zhang, J.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, C.; Ji, W.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, Z. (2015)."Exploring atomic defects in molybdenum disulphide monolayers".Nature Communications.6:6293.Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6293H.doi:10.1038/ncomms7293.PMC4346634.PMID25695374.

- ^Gmelin Handbook of Inorganic and Organometallic Chemistry - 8th edition(in German).

- ^Wypych, Fernando; Schöllhorn, Robert (1992-01-01)."1T-MoS2, a new metallic modification of molybdenum disulfide".Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications(19): 1386–1388.doi:10.1039/C39920001386.ISSN0022-4936.

- ^Enyashin, Andrey N.; Yadgarov, Lena; Houben, Lothar; Popov, Igor; Weidenbach, Marc; Tenne, Reshef; Bar-Sadan, Maya; Seifert, Gotthard (2011-12-22). "New Route for Stabilization of 1T-WS2 and MoS2 Phases".The Journal of Physical Chemistry C.115(50): 24586–24591.arXiv:1110.3848.doi:10.1021/jp2076325.ISSN1932-7447.S2CID95117205.

- ^Xu, Danyun; Zhu, Yuanzhi; Liu, Jiapeng; Li, Yang; Peng, Wenchao; Zhang, Guoliang; Zhang, Fengbao; Fan, Xiaobin (2016). "Microwave-assisted 1T to 2H phase reversion of MoS 2 in solution: a fast route to processable dispersions of 2H-MoS 2 nanosheets and nanocomposites".Nanotechnology.27(38): 385604.Bibcode:2016Nanot..27L5604X.doi:10.1088/0957-4484/27/38/385604.ISSN0957-4484.PMID27528593.S2CID23849142.

- ^Gan, Xiaorong; Lee, Lawrence Yoon Suk; Wong, Kwok-yin; Lo, Tsz Wing; Ho, Kwun Hei; Lei, Dang Yuan; Zhao, Huimin (2018-09-24)."2H/1T Phase Transition of Multilayer MoS 2 by Electrochemical Incorporation of S Vacancies".ACS Applied Energy Materials.1(9): 4754–4765.doi:10.1021/acsaem.8b00875.ISSN2574-0962.S2CID106014720.

- ^Tenne, R.; Redlich, M. (2010). "Recent progress in the research of inorganic fullerene-like nanoparticles and inorganic nanotubes".Chemical Society Reviews.39(5): 1423–34.doi:10.1039/B901466G.PMID20419198.

- ^Novoselov, K. S.; Geim, A. K.; Morozov, S. V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S. V.; Grigorieva, I. V.; Firsov, A. A. (2004-10-22). "Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films".Science.306(5696): 666–669.arXiv:cond-mat/0410550.Bibcode:2004Sci...306..666N.doi:10.1126/science.1102896.ISSN0036-8075.PMID15499015.S2CID5729649.

- ^abcCastellanos-Gomez, Andres; Poot, Menno; Steele, Gary A.; van der Zant, Herre S. J.; Agraït, Nicolás; Rubio-Bollinger, Gabino (2012-02-07). "Elastic Properties of Freely Suspended MoS2 Nanosheets".Advanced Materials.24(6): 772–775.arXiv:1202.4439.Bibcode:2012AdM....24..772C.doi:10.1002/adma.201103965.ISSN1521-4095.PMID22231284.S2CID205243099.

- ^Wan, Jiayu; Lacey, Steven D.; Dai, Jiaqi; Bao, Wenzhong; Fuhrer, Michael S.; Hu, Liangbing (2016-12-05). "Tuning two-dimensional nanomaterials by intercalation: materials, properties and applications".Chemical Society Reviews.45(24): 6742–6765.doi:10.1039/C5CS00758E.ISSN1460-4744.PMID27704060.

- ^Coleman, Jonathan N.; Lotya, Mustafa; O’Neill, Arlene; Bergin, Shane D.; King, Paul J.; Khan, Umar; Young, Karen; Gaucher, Alexandre; De, Sukanta (2011-02-04). "Two-Dimensional Nanosheets Produced by Liquid Exfoliation of Layered Materials".Science.331(6017): 568–571.Bibcode:2011Sci...331..568C.doi:10.1126/science.1194975.hdl:2262/66458.ISSN0036-8075.PMID21292974.S2CID23576676.

- ^Zhou, Kai-Ge; Mao, Nan-Nan; Wang, Hang-Xing; Peng, Yong; Zhang, Hao-Li (2011-11-11). "A Mixed-Solvent Strategy for Efficient Exfoliation of Inorganic Graphene Analogues".Angewandte Chemie.123(46): 11031–11034.Bibcode:2011AngCh.12311031Z.doi:10.1002/ange.201105364.ISSN1521-3757.

- ^abDonnet, C.; Martin, J. M.; Le Mogne, Th.; Belin, M. (1996-02-01). "Super-low friction of MoS2 coatings in various environments".Tribology International.29(2): 123–128.doi:10.1016/0301-679X(95)00094-K.

- ^Oviedo, Juan Pablo; KC, Santosh; Lu, Ning; Wang, Jinguo; Cho, Kyeongjae; Wallace, Robert M.; Kim, Moon J. (2015-02-24). "In Situ TEM Characterization of Shear-Stress-Induced Interlayer Sliding in the Cross Section View of Molybdenum Disulfide".ACS Nano.9(2): 1543–1551.doi:10.1021/nn506052d.ISSN1936-0851.PMID25494557.

- ^abTedstone, Aleksander A.; Lewis, David J.; Hao, Rui; Mao, Shi-Min; Bellon, Pascal; Averback, Robert S.; Warrens, Christopher P.; West, Kevin R.; Howard, Philip (2015-09-23)."Mechanical Properties of Molybdenum Disulfide and the Effect of Doping: An in Situ TEM Study".ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.7(37): 20829–20834.doi:10.1021/acsami.5b06055.ISSN1944-8244.PMID26322958.

- ^Tang, Dai-Ming; Kvashnin, Dmitry G.; Najmaei, Sina; Bando, Yoshio; Kimoto, Koji; Koskinen, Pekka; Ajayan, Pulickel M.; Yakobson, Boris I.; Sorokin, Pavel B. (2014-04-03)."Nanomechanical cleavage of molybdenum disulphide atomic layers".Nature Communications.5:3631.Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3631T.doi:10.1038/ncomms4631.PMID24698887.

- ^abcBertolazzi, Simone; Brivio, Jacopo; Kis, Andras (2011)."Stretching and Breaking of Ultrathin MoS2".ACS Nano.5(12): 9703–9709.doi:10.1021/nn203879f.PMID22087740.

- ^Jiang, Jin-Wu; Park, Harold S.; Rabczuk, Timon (2013-08-12). "Molecular dynamics simulations of single-layer molybdenum disulphide (MoS2): Stillinger-Weber parametrization, mechanical properties, and thermal conductivity".Journal of Applied Physics.114(6): 064307–064307–10.arXiv:1307.7072.Bibcode:2013JAP...114f4307J.doi:10.1063/1.4818414.ISSN0021-8979.S2CID119304891.

- ^Li, H.; Wu, J.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, H. (2014). "Preparation and Applications of Mechanically Exfoliated Single-Layer and Multilayer MoS2and WSe2Nanosheets ".Acc. Chem. Res.47(4): 1067–75.doi:10.1021/ar4002312.PMID24697842.

- ^Amorim, B.; Cortijo, A.; De Juan, F.; Grushin, A.G.; Guinea, F.; Gutiérrez-Rubio, A.; Ochoa, H.; Parente, V.; Roldán, R.; San-Jose, P.; Schiefele, J.; Sturla, M.; Vozmediano, M.A.H. (2016). "Novel effects of strains in graphene and other two dimensional materials".Physics Reports.1503:1–54.arXiv:1503.00747.Bibcode:2016PhR...617....1A.doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2015.12.006.S2CID118600177.

- ^Zhang, X.; Lai, Z.; Tan, C.; Zhang, H. (2016). "Solution-Processed Two-Dimensional MoS2Nanosheets: Preparation, Hybridization, and Applications ".Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.55(31): 8816–8838.doi:10.1002/anie.201509933.PMID27329783.

- ^Stephenson, T.; Li, Z.; Olsen, B.; Mitlin, D. (2014). "Lithium Ion Battery Applications of Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) Nanocomposites ".Energy Environ. Sci.7:209–31.doi:10.1039/C3EE42591F.

- ^Benavente, E.; Santa Ana, M. A.; Mendizabal, F.; Gonzalez, G. (2002). "Intercalation chemistry of molybdenum disulfide".Coordination Chemistry Reviews.224(1–2): 87–109.doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(01)00392-7.hdl:10533/173130.

- ^Müller-Warmuth, W. & Schöllhorn, R. (1994).Progress in intercalation research.Springer.ISBN978-0-7923-2357-0.

- ^abHigh Performance, Dry Powdered Graphite with sub-micron molybdenum disulfide.pinewoodpro.com

- ^Claus, F. L. (1972), "Solid Lubricants and Self-Lubricating Solids",New York: Academic Press,Bibcode:1972slsl.book.....C

- ^Miessler, Gary L.; Tarr, Donald Arthur (2004).Inorganic Chemistry.Pearson Education.ISBN978-0-13-035471-6.

- ^Shriver, Duward; Atkins, Peter; Overton, T. L.; Rourke, J. P.; Weller, M. T.; Armstrong, F. A. (17 February 2006).Inorganic Chemistry.W. H. Freeman.ISBN978-0-7167-4878-6.

- ^"On dry lubricants in ski waxes"(PDF).Swix Sport AX. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-16.Retrieved2011-01-06.

- ^"Barrels retain accuracy longer with Diamond Line".Norma.Retrieved2009-06-06.

- ^Bartels, Thorsten; et al. (2002). "Lubricants and Lubrication".Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry.Weinheim: Wiley VCH.doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_423.ISBN978-3527306732.

- ^Topsøe, H.; Clausen, B. S.; Massoth, F. E. (1996).Hydrotreating Catalysis, Science and Technology.Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ^abNishimura, Shigeo (2001).Handbook of Heterogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenation for Organic Synthesis(1st ed.). New York: Wiley-Interscience. pp. 43–44 & 240–241.ISBN9780471396987.

- ^Dovell, Frederick S.; Greenfield, Harold (1964). "Base-Metal Sulfides as Reductive Alkylation Catalysts".The Journal of Organic Chemistry.29(5): 1265–1267.doi:10.1021/jo01028a511.

- ^Wood, Charlie (2022-08-16)."Physics Duo Finds Magic in Two Dimensions".Quanta Magazine.Retrieved2022-08-19.

- ^Kibsgaard, Jakob; Jaramillo, Thomas F.; Besenbacher, Flemming (2014)."Building an appropriate active-site motif into a hydrogen-evolution catalyst with thiomolybdate [Mo3S13]2−clusters ".Nature Chemistry.6(3): 248–253.Bibcode:2014NatCh...6..248K.doi:10.1038/nchem.1853.PMID24557141.

- ^Laursen, A. B.; Kegnaes, S.; Dahl, S.; Chorkendorff, I. (2012). "Molybdenum Sulfides – Efficient and Viable Materials for Electro- and Photoelectrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution".Energy Environ. Sci.5(2): 5577–91.doi:10.1039/c2ee02618j.

- ^"Superior hydrogen catalyst just grows that way"(news release).share-ng.sandia.gov.Sandia Labs.RetrievedDecember 5,2017.

a spray-printing process that uses molybdenum disulfide to create a "flowering" hydrogen catalyst far cheaper than platinum and reasonably close in efficiency.

- ^Yan, Yan; Liang, Shuang; Wang, Xiang; Zhang, Mingyue; Hao, Shu-Meng; Cui, Xun; Li, Zhiwei; Lin, Zhiqun (2021-10-05)."Robust wrinkled MoS 2 /N-C bifunctional electrocatalysts interfaced with single Fe atoms for wearable zinc-air batteries".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.118(40): e2110036118.Bibcode:2021PNAS..11810036Y.doi:10.1073/pnas.2110036118.ISSN0027-8424.PMC8501804.PMID34588309.

- ^Wang, Q. H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kis, A.; Coleman, J. N.; Strano, M. S. (2012)."Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides".Nature Nanotechnology.7(11): 699–712.Bibcode:2012NatNa...7..699W.doi:10.1038/nnano.2012.193.PMID23132225.S2CID6261931.

- ^abGanatra, R.; Zhang, Q. (2014). "Few-Layer MoS2:A Promising Layered Semiconductor ".ACS Nano.8(5): 4074–99.doi:10.1021/nn405938z.PMID24660756.

- ^Zhu, Wenjuan; Low, Tony; Lee, Yi-Hsien; Wang, Han; Farmer, Damon B.; Kong, Jing; Xia, Fengnian; Avouris, Phaedon (2014). "Electronic transport and device prospects of monolayer molybdenum disulphide grown by chemical vapour deposition".Nature Communications.5:3087.arXiv:1401.4951.Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3087Z.doi:10.1038/ncomms4087.PMID24435154.S2CID6075401.

- ^Hong, Jinhua; Hu, Zhixin; Probert, Matt; Li, Kun; Lv, Danhui; Yang, Xinan; Gu, Lin; Mao, Nannan; Feng, Qingliang; Xie, Liming; Zhang, Jin; Wu, Dianzhong; Zhang, Zhiyong; Jin, Chuanhong; Ji, Wei; Zhang, Xixiang; Yuan, Jun; Zhang, Ze (2015)."Exploring atomic defects in molybdenum disulphide monolayers".Nature Communications.6:6293.Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6293H.doi:10.1038/ncomms7293.PMC4346634.PMID25695374.

- ^Splendiani, A.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Kim, J.; Chim, J.; F.; Wang, Feng (2010). "Emerging Photoluminescence in Monolayer MoS2".Nano Letters.10(4): 1271–1275.Bibcode:2010NanoL..10.1271S.doi:10.1021/nl903868w.PMID20229981.

- ^abRadisavljevic, B.; Radenovic, A.; Brivio, J.; Giacometti, V.; Kis, A. (2011)."Single-layer MoS2transistors ".Nature Nanotechnology.6(3): 147–150.Bibcode:2011NatNa...6..147R.doi:10.1038/nnano.2010.279.PMID21278752.

- ^Lopez-Sanchez, O.; Lembke, D.; Kayci, M.; Radenovic, A.; Kis, A. (2013)."Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2".Nature Nanotechnology.8(7): 497–501.Bibcode:2013NatNa...8..497L.doi:10.1038/nnano.2013.100.PMID23748194.S2CID5435971.

- ^Rao, C. N. R.; Ramakrishna Matte, H. S. S.; Maitra, U. (2013). "Graphene Analogues of Inorganic Layered Materials".Angew. Chem.52(50) (International ed.): 13162–85.doi:10.1002/anie.201301548.PMID24127325.

- ^Bessonov, A. A.; Kirikova, M. N.; Petukhov, D. I.; Allen, M.; Ryhänen, T.; Bailey, M. J. A. (2014). "Layered memristive and memcapacitive switches for printable electronics".Nature Materials.14(2): 199–204.Bibcode:2015NatMa..14..199B.doi:10.1038/nmat4135.PMID25384168.

- ^"Ultrasensitive biosensor from molybdenite semiconductor outshines graphene".R&D Magazine.4 September 2014.

- ^Akinwande, Deji; Petrone, Nicholas; Hone, James (2014-12-17)."Two-dimensional flexible nanoelectronics".Nature Communications.5:5678.Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.5678A.doi:10.1038/ncomms6678.PMID25517105.

- ^Chang, Hsiao-Yu; Yogeesh, Maruthi Nagavalli; Ghosh, Rudresh; Rai, Amritesh; Sanne, Atresh; Yang, Shixuan; Lu, Nanshu; Banerjee, Sanjay Kumar; Akinwande, Deji (2015-12-01)."Large-Area Monolayer MoS2for Flexible Low-Power RF Nanoelectronics in the GHz Regime ".Advanced Materials.28(9): 1818–1823.doi:10.1002/adma.201504309.PMID26707841.S2CID205264837.

- ^Wachter, Stefan; Polyushkin, Dmitry K.; Bethge, Ole; Mueller, Thomas (2017-04-11)."A microprocessor based on a two-dimensional semiconductor".Nature Communications.8:14948.arXiv:1612.00965.Bibcode:2017NatCo...814948W.doi:10.1038/ncomms14948.ISSN2041-1723.PMC5394242.PMID28398336.

- ^"Memtransistors advance neuromorphic computing | NextBigFuture.com".NextBigFuture.com.2018-02-24.Retrieved2018-02-27.

- ^Mak, Kin Fai; He, Keliang; Shan, Jie; Heinz, Tony F. (2012)."Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS2 by optical helicity".Nature Nanotechnology.7(8): 494–498.arXiv:1205.1822.Bibcode:2012NatNa...7..494M.doi:10.1038/nnano.2012.96.PMID22706698.S2CID23248686.

- ^Wu, Zefei; Zhou, Benjamin T.; Cai, Xiangbin; Cheung, Patrick; Liu, Gui-Bin; Huang, Meizhen; Lin, Jiangxiazi; Han, Tianyi; An, Liheng; Wang, Yuanwei; Xu, Shuigang; Long, Gen; Cheng, Chun; Law, Kam Tuen; Zhang, Fan (2019-02-05)."Intrinsic valley Hall transport in atomically thin MoS2".Nature Communications.10(1): 611.arXiv:1805.06686.Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..611W.doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08629-9.PMC6363770.PMID30723283.

- ^Coxworth, Ben (September 25, 2014)."Metal-based graphene alternative" shines "with promise".Gizmag.RetrievedSeptember 30,2014.

- ^Taniguchi, Kouji; Matsumoto, Akiyo; Shimotani, Hidekazu; Takagi, Hidenori (July 23, 2012)."Electric-field-induced superconductivity at 9.4 K in a layered transition metal disulphide MoS2".Applied Physics Letters.101(4): 042603.Bibcode:2012ApPhL.101d2603T.doi:10.1063/1.4740268– via aip.scitation.org (Atypon).

External links

edit- Wood, Charlie (2022-08-16)."Physics Duo Finds Magic in Two Dimensions".Quanta Magazine.Retrieved2022-08-19.