Moravia[a](Czech:Morava[ˈmorava];German:Mähren) is ahistorical regionin the east of theCzech Republicand one of three historicalCzech lands,withBohemiaandCzech Silesia.

Moravia

Morava | |

|---|---|

| |

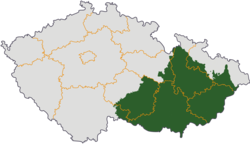

Moravia (green) overlapped with the currentregions of the Czech Republic | |

Location of Moravia in theEuropean Union | |

| Coordinates:49°30′N17°00′E/ 49.5°N 17°E | |

| Country | Czech Republic |

| Regions | Moravian-Silesian,Olomouc,South Moravian,Vysočina,Zlín,South Bohemian,Pardubice |

| First mentioned | 822[1][2] |

| Consolidated | 833[3] |

| Former capital | Brno(1641–1948)[4] Brno,Olomouc(until 1641),Velehrad(9th century) |

| Major cities | Brno,Ostrava,Olomouc,Zlín,Jihlava |

| Area | |

| • Total | 22,348.87 km2(8,628.95 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 3,180,000 |

| • Density | 140/km2(370/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Moravian |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Primary airport | Brno–Tuřany Airport |

| Highways | |

The medieval and early modernMargraviate of Moraviawas acrown landof theLands of the Bohemian Crownfrom 1348 to 1918, animperial stateof theHoly Roman Empirefrom 1004 to 1806, a crown land of theAustrian Empirefrom 1804 to 1867, and a part ofAustria-Hungaryfrom 1867 to 1918. Moravia was one of the five lands ofCzechoslovakiafounded in 1918. In 1928 it was merged withCzech Silesia,and then dissolved in 1948 during the abolition of the land system following thecommunist coup d'état.

Its area of 22,623.41 km2[b]is home to about 3.2 million of the Czech Republic's 10.9 million inhabitants.[5]The people are historically namedMoravians,a subgroup ofCzechs,the other group being calledBohemians.[11][12]The land takes its name from theMoravariver, which runs from its north to south, being its principal watercourse. Moravia's largest city and historical capital isBrno.Before being sacked by theSwedish armyduring theThirty Years' War,Olomoucserved as the Moravian capital, and it is still the seat of theArchdiocese of Olomouc.[4]Until theexpulsions after 1945,significant parts of Moravia wereGerman speaking.

Toponymy

editThe region and former margraviate of Moravia,Moravain Czech, is named after itsprincipalriverMorava.It is theorized that the river's name is derived fromProto-Indo-European*mori:"waters", or indeed any word denotingwateror amarsh.[13]

The German name for Moravia isMähren,from the river's German nameMarch.This could have a different etymology, asmarchis a term used in the Medieval times for an outlying territory, a border or a frontier (cf. Englishmarch). In Latin, the name Moravia was used.

Geography

editMoravia occupies most of the eastern part of theCzech Republic.Moravian territory is naturally strongly determined, in fact, as theMoravariver basin,with strong effect of mountains in the west (de factomainEuropean continental divide) and partly in the east, where all therivers rise.

Moravia occupies an exceptional position in Central Europe. All thehighlandsin the west and east of this part of Europe run west–east, and therefore form a kind of filter, making north–south or south–north movement more difficult. Only Moravia with the depression of the westernmostOuter Subcarpathia,14–40 kilometers (8.7–24.9 mi) wide, between theBohemian Massifand theOuter Western Carpathians(gripping themeridianat a constant angle of 30°), provides a comfortable connection between theDanubianandPolish regions,and this area is thus of great importance in terms of the possible migration routes of large mammals[14]– both as regards periodically recurring seasonal migrations triggered by climatic oscillations in theprehistory,when permanentsettlementstarted.

Moravia bordersBohemiain the west,Lower Austriain the southwest,Slovakiain the southeast,Polandvery shortly in the north, andCzech Silesiain the northeast. Its natural boundary is formed by theSudetesmountains in the north, theCarpathiansin the east and theBohemian-Moravian Highlandsin the west (the border runs fromKrálický Sněžníkin the north, overSuchý vrch,acrossUpper Svratka HighlandsandJavořice HighlandstotripointnearbySlavonicein the south). TheThayariver meanders along the border withAustriaand thetripointof Moravia,AustriaandSlovakiais at theconfluenceof the Thaya and Morava rivers. The northeast border with Silesia runs partly along theMoravice,OderandOstravicerivers. Between 1782 and 1850, Moravia (also thus known asMoravia-Silesia) also included a small portion of the former province ofSilesia– theAustrian Silesia(when Frederick the Great annexed most of ancient Silesia (the land of upper and middle Oder river) toPrussia,Silesia's southernmost part remained with theHabsburgs).

Today Moravia includes theSouth MoravianandZlínregions, vast majority of theOlomouc Region,southeastern half of theVysočina Regionand parts of theMoravian-Silesian,PardubiceandSouth Bohemianregions.

Geologically, Moravia covers a transitive area[clarification needed]between theBohemian Massifand the Carpathians (from northwest to southeast), and between theDanubebasin and theNorth European Plain(from south to northeast). Its core geomorphological features are three wide valleys, namely theDyje-Svratka Valley(Dyjsko-svratecký úval), theUpper Morava Valley(Hornomoravský úval) and theLower Morava Valley(Dolnomoravský úval). The first two form the westernmost part of theOuter Subcarpathia,the last is the northernmost part of theVienna Basin.The valleys surround the low range ofCentral Moravian Carpathians.The highest mountains of Moravia are situated on its northern border inHrubý Jeseník,the highest peak isPraděd(1491 m). Second highest is the massive of Králický Sněžník (1424 m) the third are theMoravian-Silesian Beskidsat the very east, withSmrk(1278 m), and then south from hereJavorníky(1072). TheWhite Carpathiansalong the southeastern border rise up to 970 m atVelká Javořina.The spacious, but moderateBohemian-Moravian Highlandson the west reach 837 m atJavořice.

The fluvial system of Moravia is very cohesive, as the region border is similar to the watershed of the Morava river, and thus almost the entire area is drained exclusively by a single stream. Morava's far biggest tributaries are Thaya (Dyje) from the right (or west) andBečva(east). Morava and Thaya meet at the southernmost and lowest (148 m) point of Moravia. Small peripheral parts of Moravia belong to the catchment area ofElbe,Váhand especiallyOder(the northeast). The watershed line running along Moravia's border from west to north and east is part of theEuropean Watershed.For centuries, there have been plans to build awaterwayacross Moravia tojoin the Danube and Oderriver systems, using the natural route through theMoravian Gate.[15][16]

History

editPre-history

editEvidence of the presence of members of the human genus,Homo,dates back more than 600,000 years in thepaleontologicalarea ofStránská skála.[14]

Attracted by suitable living conditions, early modern humans settled in the region by thePaleolithicperiod. ThePředmostí archeological(Cro-magnon) site in Moravia is dated to between 24,000 and 27,000 years old.[17][18]Caves inMoravian Karstwere used bymammoth hunters.Venus of Dolní Věstonice,the oldest ceramic figure in the world,[19][20]was found in the excavation ofDolní VěstonicebyKarel Absolon.[21]

Roman era

editAround 60 BC, theCelticVolcaepeople withdrew from the region and were succeeded by theGermanicQuadi.Some of the events of theMarcomannic Warstook place in Moravia in AD 169–180. After the war exposed the weakness ofRome's northern frontier,half of theRoman legions(16 out of 33) were stationed along theDanube.In response to increasing numbers ofGermanicsettlers in frontier regions likePannonia,Dacia,Rome established two new frontier provinces on the left shore of the Danube,MarcomanniaandSarmatia,including today's Moravia and westernSlovakia.

In the 2nd century AD, aRoman fortress[22][23]stood on the vineyards hill known as German:BurgstallandCzech:Hradisko( "hillfort"), situated above the former villageMušovand above today's beach resort atPasohlávky.During the reign of the EmperorMarcus Aurelius,the10th Legionwas assigned to control the Germanic tribes who had been defeated in the Marcomannic Wars.[24]In 1927, the archeologist Gnirs, with the support of presidentTomáš Garrigue Masaryk,began research on the site, located 80 km fromVindobonaand 22 km to the south of Brno. The researchers found remnants of two masonry buildings, apraetorium[25]and abalneum( "bath" ), including ahypocaustum.The discovery of bricks with the stamp of theLegio X Geminaand coins from the period of the emperorsAntoninus Pius,Marcus AureliusandCommodusfacilitated dating of the locality.

Ancient Moravia

editA variety of Germanic and majorSlavictribes crossed through Moravia during theMigration Periodbefore Slavs established themselves in the 6th century AD. At the end of the 8th century, the Moravian Principality came into being in present-day south-eastern Moravia,Záhoriein south-western Slovakia and parts ofLower Austria.In 833 AD, this became the state ofGreat Moravia[26]with the conquest of thePrincipality of Nitra(present-day Slovakia). Their first king wasMojmír I(ruled 830–846).Louis the Germaninvaded Moravia and replaced Mojmír I with his nephewRastizwho became St. Rastislav.[27]St. Rastislav (846–870) tried to emancipate his land from theCarolingian influence,so he sent envoys to Rome to get missionaries to come. When Rome refused he turned toConstantinopleto theByzantine emperor Michael.The result was the mission ofSaints Cyril and Methodiuswho translatedliturgical booksintoSlavonic,which had lately been elevated by the Pope to the same level as Latin and Greek. Methodius became the first Moravian archbishop, the first archbishop in Slavic world, but after his death the German influence again prevailed and the disciples of Methodius were forced to flee. Great Moravia reached its greatest territorial extent in the 890s underSvatopluk I.At this time, the empire encompassed the territory of the present-dayCzech RepublicandSlovakia,the western part of presentHungary(Pannonia), as well asLusatiain present-day Germany andSilesiaand the upperVistulabasin in southernPoland.After Svatopluk's death in 895, the Bohemian princes defected to become vassals of the East Frankish rulerArnulf of Carinthia,and the Moravian state ceased to exist after being overrun byinvading Magyarsin 907.[28][29]

Union with Bohemia

editFollowing the defeat of the Magyars by EmperorOtto Iat theBattle of Lechfeldin 955, Otto's allyBoleslaus I,thePřemyslidruler ofBohemia,took control over Moravia.Bolesław I Chrobryof Poland annexed Moravia in 999, and ruled it until 1019,[30]when the Přemyslid princeBretislausrecaptured it. Upon his father's death in 1034, Bretislaus became the ruler of Bohemia. In 1055, he decreed that Bohemia and Moravia would be inherited together byprimogeniture,although he also provided that his younger sons should govern parts (quarters) of Moravia as vassals to his oldest son.

Throughout the Přemyslid era, junior princes often ruled all or part of Moravia fromOlomouc,BrnoorZnojmo,with varying degrees of autonomy from the ruler of Bohemia. Dukes of Olomouc often acted as the "right hand" of Prague dukes and kings, while Dukes of Brno and especially those of Znojmo were much more insubordinate. Moravia reached its height of autonomy in 1182, when EmperorFrederick IelevatedConrad II Otto of Znojmoto the status of amargrave,[31]immediately subject to the emperor, independent of Bohemia. This status was short-lived: in 1186, Conrad Otto was forced to obey the supreme rule ofBohemian dukeFrederick.Three years later, Conrad Otto succeeded to Frederick as Duke of Bohemia and subsequently canceled his margrave title. Nevertheless, the margrave title was restored in 1197 whenVladislaus III of Bohemiaresolved the succession dispute between him and his brotherOttokarby abdicating from the Bohemian throne and accepting Moravia as a vassal land of Bohemian (i.e., Prague) rulers. Vladislaus gradually established this land asMargraviate,slightly administratively different from Bohemia. After theBattle of Legnica,theMongolscarried their raids into Moravia.

The main line of thePřemysliddynasty became extinct in 1306, and in 1310John of Luxembourgbecame Margrave of Moravia and King of Bohemia. In 1333, he made his sonCharlesthe next Margrave of Moravia (later in 1346, Charles also became the King of Bohemia). In 1349, Charles gave Moravia to his younger brotherJohn Henrywho ruled in the margraviate until his death in 1375, after him Moravia was ruled by his oldest sonJobst of Moraviawho was in 1410 elected the Holy Roman King but died in 1411 (he is buried with his father in theChurch of St. Thomas in Brno– the Moravian capital from which they both ruled). Moravia and Bohemia remained within theLuxembourg dynastyof Holy Roman kings and emperors (except during theHussite wars), until inherited byAlbert II of Habsburgin 1437.

After his death followed theinterregnumuntil 1453; land (as the rest of lands of the Bohemian Crown) was administered by thelandfriedens(landfrýdy). The rule of youngLadislaus the Posthumoussubsisted only less than five years and subsequently (1458) the HussiteGeorge of Poděbradywas elected as the king. He again reunited all Czech lands (then Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Upper & Lower Lusatia) into one-man ruled state. In 1466,Pope Paul IIexcommunicated George and forbade all Catholics (i.e. about 15% of population) from continuing to serve him. The Hungariancrusadefollowed and in 1469Matthias Corvinusconquered Moravia and proclaimed himself (with assistance of rebellingBohemian nobility) as the king of Bohemia.

The subsequent 21-year period of a divided kingdom was decisive for the rising awareness of a specific Moravian identity, distinct from that of Bohemia. Although Moravia was reunited with Bohemia in 1490 whenVladislaus Jagiellon,king of Bohemia, also became king of Hungary, some attachment to Moravian "freedoms" and resistance to government by Prague continued until the end of independence in 1620. In 1526, Vladislaus' sonLouisdied in battle and the HabsburgFerdinand Iwas elected as his successor.

-

Bohemia and Moravia in the 12th century

-

Church of St. Thomas in Brno,mausoleum of Moravian branchHouse of Luxembourg,rulers of Moravia; and the old governor's palace, a former Augustinian abbey

-

12th century RomanesqueSt. Procopius Basilica in Třebíč

Habsburg rule (1526–1918)

editAfter the death of KingLouis II of Hungary and Bohemiain 1526,Ferdinand IofAustriawas elected King of Bohemia and thus ruler of the Crown of Bohemia (including Moravia). The epoch 1526–1620 was marked by increasing animosity between Catholic Habsburg kings (emperors) and the Protestant Moravian nobility (and other Crowns') estates. Moravia,[34]like Bohemia, was a Habsburg possession until the end ofWorld War I.In 1573 theJesuitUniversity of Olomoucwas established; this was the first university in Moravia. The establishment of a special papal seminary, Collegium Nordicum, made the University a centre of the Catholic Reformation and effort to revive Catholicism in Central and Northern Europe. The second largest group of students were fromScandinavia.

Brno and Olomouc served as Moravia's capitals until 1641. As the only city to successfully resist the Swedish invasion, Brno become the sole capital following the capture of Olomouc. The Margraviate of Moravia had, from 1348 in Olomouc and Brno, its ownDiet, or parliament,zemský sněm(Landtagin German), whose deputies from 1905 onward were elected separately from the ethnically separate German and Czech constituencies.

The oldest surviving theatre building in Central Europe, theReduta Theatre,was established in 17th-century Moravia. OttomanTurksandTatarsinvaded the region in 1663, taking 12,000 captives.[35]In 1740, Moravia was invaded by Prussian forces underFrederick the Great,and Olomouc was forced to surrender on 27 December 1741. A few months later the Prussians were repelled, mainly because of their unsuccessful siege of Brno in 1742. In 1758, Olomouc wasbesieged by Prussiansagain, but this time its defenders forced the Prussians to withdraw following theBattle of Domstadtl.In 1777, a new Moravian bishopric was established in Brno, and the Olomouc bishopric was elevated to an archbishopric.[36]In 1782, the Margraviate of Moravia was merged withAustrian SilesiaintoMoravia-Silesia,with Brno as its capital. Moravia became a separate crown land of Austria again in 1849,[37][38]and then became part ofCisleithanianAustria-Hungary after 1867. According to Austro-Hungarian census of 1910 the proportion of Czechs in the population of Moravia at the time (2.622.000) was 71.8%, while the proportion of Germans was 27.6%.[39]

-

Administrative division of Moravia as crown land of Austria in 1893

20th century

editFollowing the break-up of theAustro-Hungarian Empirein 1918, Moravia became part ofCzechoslovakia.As one of the five lands of Czechoslovakia, it had restricted autonomy. In 1928 Moravia ceased to exist as a territorial unity and was merged withCzech Silesiainto the Moravian-Silesian Land (yet with the natural dominance of Moravia). By theMunich Agreement(1938), the southwestern and northern peripheries of Moravia, which had a German-speaking majority, were annexed byNazi Germany,and during the Germanoccupation of Czechoslovakia(1939–1945), the remnant of Moravia was an administrative unit within theProtectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

DuringWorld War II,the Germans operated multipleforced labourcamps in the region, including several subcamps of theStalag VIII-B/344prisoner-of-war campforAlliedPOWs,[40]asubcampof theAuschwitz concentration campinBrnofor mostlyPolishprisoners,[41]and a subcamp of theGross-Rosen concentration campinBílá Vodafor Jewish women.[42]The occupiers also established several POW camps, including Heilag VIII-H,Oflag VIII-Fand Oflag VIII-H, forFrench,British, Belgian and other Allied POWs in the region.[43]

In 1945 after the Allied defeat of Germany and the end of World War II, the German minority wasexpelledto Germany andAustriain accordance with thePotsdam Agreement.The Moravian-Silesian Land was restored with Moravia as part of it and towns and villages that were left by the former German inhabitants, were re-settled by Czechs,Slovaksand reemigrants.[44]In 1949 the territorial division of Czechoslovakia was radically changed, as the Moravian-Silesian Land was abolished and Lands were replaced by "kraje"(regions), whose borders substantially differ from the historical Bohemian-Moravian border, so Moravia politically ceased to exist after more than 1100 years (833–1949) of its history. Although another administrative reform in 1960 implemented (among others) the North Moravian and the South Moravian regions (SeveromoravskýandJihomoravský kraj), with capitals in Ostrava and Brno respectively, their joint area was only roughly alike the historical state and, chiefly, there was no land or federal autonomy, unlike Slovakia.

After the fall of theSoviet Unionand the wholeEastern Bloc,the CzechoslovakFederal Assemblycondemned the cancellation of Moravian-Silesian land and expressed "firm conviction that this injustice will be corrected" in 1990. However, after thebreakupof Czechoslovakia intoCzech RepublicandSlovakiain 1993, Moravian area remained integral to the Czech territory, and the latest administrative division of Czech Republic (introduced in 2000) is similar to the administrative division of 1949. Nevertheless, thefederalistorseparatistmovement in Moravia is completely marginal.

The centuries-lasting historical Bohemian-Moravian border has been preserved up to now only by theCzech Roman Catholic Administration,as the Ecclesiastical Province of Moravia corresponds with the former Moravian-Silesian Land. The popular perception of the Bohemian-Moravian border's location is distorted by the memory of the 1960 regions (whose boundaries are still partly in use).

-

Jan Černý,president of Moravia in 1922–1926, later also Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia

-

A general map of Moravia in the 1920s

-

In 1928, Moravia was merged into Moravia-Silesia, one of four lands of Czechoslovakia, together with Bohemia,SlovakiaandSubcarpathian Rus.

Economy

editAn area inSouth Moravia,aroundHodonínandBřeclav,is part of theViennese Basin.Petroleum andligniteare found there in abundance. The main economic centres of Moravia areBrno,Olomouc,Zlín,andOstravalying directly on the Moravian–Silesian border. As well as agriculture in general, Moravia is noted for itsviticulture;it contains 94% of the Czech Republic'svineyardsand is at the centre of thecountry's wine industry.Wallachiahas at least a 400-year-old tradition ofslivovitzmaking.[45]

The Czech automotive industry also played a significant role in Moravia's economy in the 20th century; the factories ofWikovinProstějovandTatrainKopřivniceproduced many automobiles.

Moravia is also the centre of the Czech firearm industry, as the vast majority of Czech firearms manufacturers (e.g.CZUB,Zbrojovka Brno,Czech Small Arms,Czech Weapons,ZVI,Great Gun) are found in Moravia. Almost all the well-known Czech sporting, self-defence, military, and hunting firearms are made in Moravia.Meoptarifle scopes are of Moravian origin. Theoriginal Bren gunwas conceived here, as were the assault rifles theCZ-805 BRENandSa vz. 58,and the handgunsCZ 75andZVI Kevin(also known as the "MicroDesert Eagle").

TheZlín Regionhosts several aircraft manufacturers, namelyLet Kunovice(also known as Aircraft Industries, a.s.),ZLIN AIRCRAFT a.s. Otrokovice(formerly known under the nameMoravanOtrokovice),Evektor-Aerotechnik,andCzech Sport Aircraft.Sport aircraft are also manufactured inJihlavabyJihlavan Airplanes/Skyleader.

Aircraft production in the region started in the 1930s; after a period of low production post-1989, there have been signs of recovery post-2010, and production is expected to grow from 2013 onwards.[46]

Companies with operations in Brno includeGen Digital,which maintains one of its headquarters there and continues to use the brandAVG Technologies,[47]as well asKyndryl(Client Innovation Centre),[48][49]AT&T,andHoneywell(Global Design Center).[50]Other significant companies includeSiemens,[51]Red Hat(Czech headquarters),[52]and an office ofZebra Technologies.[53]

In recent years, Brno's economy has seen growth in the quaternary sector, focusing on science, research, and education. Notable projects include AdMaS (Advanced Materials, Structures, and Technologies) and CETOCOEN (Center for Research on Toxic Substances in the Environment).[54]

-

TheTatra 77(1934)

-

WIKOV Supersport (1931)

-

ThonetNo. 14 chair

-

The speed train TatraM 290.0 Slovenská strela1936

-

Zlín XIIIaircraft on display at theNational Technical Museumin Prague

-

Zetor 25A tractor

-

Electron microscope Brno

-

Aeroplane L 410 NG byLet Kunovice

-

Precise rifle scope by MeOpta

-

The (modern) BREN gun M 2 11

-

The modern EVO 2 tram

-

Diesel railway coach class Bfhpvee295

Machinery industry

editThe machinery industry has been the most important industrial sector in the region, especially inSouth Moravia,for many decades. The main centres of machinery production are Brno (Zbrojovka Brno,Zetor,První brněnská strojírna,Siemens),Blansko(ČKD Blansko,Metra),Kuřim(TOS Kuřim),Boskovice(Minerva,Novibra) andBřeclav(Otis Elevator Company). A number of other, smaller machinery and machine parts factories, companies, and workshops are spread over Moravia.

Electrical industry

editThe beginnings of the electrical industry in Moravia date back to 1918. The biggest centres of electrical production are Brno (VUES,ZPA Brno,EM Brno),Drásov,Frenštát pod Radhoštěm,andMohelnice(currently Siemens).

Cities and towns

editCities

edit- Brno,c. 396,000 inhabitants, former land capital and nowadays capital ofSouth Moravian Region;industrial, judicial, educational and research centre; railway and motorway junction

- Ostrava,c. 284,000 inh. (central part,Moravská Ostrava,lies historically in Moravia, most of the outskirts are inCzech Silesia), capital ofMoravian-Silesian Region,centre of heavy industry

- Olomouc,c. 102,000 inh., capital ofOlomouc Region,medieval land capital, seat of Roman Catholic archbishop, cultural centre ofHanakiaand Central Moravia

- Zlín,c. 74,000 inh., capital ofZlín Region,modern city developed afterWorld War Iby theBata Shoescompany

- Frýdek-Místek,c. 54,000 inh., twin-city lying directly on the old Moravian-Silesian border (the western part, Místek, is Moravian), in the industrial area around Ostrava

- Jihlava,c. 53,000 inh. (mostly in Moravia, northwestern periphery lies in Bohemia), capital ofVysočina Region,centre of theMoravian Highlands

- Prostějov,c. 44,000 inh., former centre of clothing and fashion industry, birthplace ofEdmund Husserl

- Přerov,c. 42,000 inh., important railway hub and archeological site (Předmostí)

Towns

edit- Třebíč(35,000), another centre in the Highlands, with exceptionally preserved Jewish quarter

- Znojmo(34,000), historical and cultural centre of southwestern Moravia

- Kroměříž(28,000), historical town in southern Hanakia

- Vsetín(25,000), centre of theMoravian Wallachia

- Šumperk(25,000), centre of the north of Moravia, at the foot ofHrubý Jeseník

- Uherské Hradiště(25,000), cultural centre of theMoravian Slovakia

- Břeclav(25,000), important railway hub in the very south of Moravia

- Hodonín(24,000), another town in the Moravian Slovakia, the birthplace ofTomáš Garrigue Masaryk

- Nový Jičín(23,000), historical town with hatting industry

- Valašské Meziříčí(23,000), centre of chemical industry inMoravian Wallachia

- Kopřivnice(22,000), centre of automotive industry (Tatra), south from Ostrava

- Žďár nad Sázavou(21,000), industrial town in the Highlands, near the border with Bohemia

- Vyškov(20,000), local centre at a motorway junction halfway between Brno and Olomouc

- Blansko(20,000), industrial town north from Brno, at the foot of theMoravian Karst

People

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1869 | 2,076,555 | — |

| 1880 | 2,181,555 | +5.1% |

| 1890 | 2,305,109 | +5.7% |

| 1900 | 2,464,913 | +6.9% |

| 1910 | 2,652,601 | +7.6% |

| 1921 | 2,679,750 | +1.0% |

| 1930 | 2,842,976 | +6.1% |

| 1950 | 2,614,435 | −8.0% |

| 1961 | 2,841,692 | +8.7% |

| 1970 | 2,937,155 | +3.4% |

| 1980 | 3,126,530 | +6.4% |

| 1991 | 3,160,751 | +1.1% |

| 2001 | 3,140,709 | −0.6% |

| 2011 | 3,110,649 | −1.0% |

| 2021 | 3,103,408 | −0.2% |

| Source: Censuses[55][56] | ||

The Moravians are generally a Slavic ethnic group who speak various (generally more archaic) dialects ofCzech.Before the expulsion ofGermansfrom Moravia the Moravian German minority also referred to themselves as "Moravians" (Mährer). Those expelled and their descendants continue to identify as Moravian. [57]Some Moravians assert thatMoravianis a language distinct fromCzech;however, their position is not widely supported by academics and the public.[58][59][60][61]Some Moravians identify as an ethnically distinct group; the majority consider themselves to be ethnically Czech. In the census of 1991 (the first census in history in which respondents were allowed to claim Moravian nationality), 1,362,000 (13.2%) of the Czech population identified as being of Moravian nationality (or ethnicity). In some parts of Moravia (mostly in the centre and south), majority of the population identified as Moravians, rather than Czechs. In the census of 2001, the number of Moravians had decreased to 380,000 (3.7% of the country's population).[62]In the census of 2011, this number rose to 522,474 (4.9% of the Czech population).[63][64]

Moravia historically had a large minority ofethnic Germans,some of whom had arrived as early as the 13th century at the behest of thePřemyslid dynasty.Germans continued to come to Moravia in waves, culminating in the 18th century. They lived in the main city centres and in the countryside along the border with Austria (stretching up to Brno) and along the border with Silesia at Jeseníky, and also in twolanguage islands,around Jihlava and aroundMoravská Třebová.After theWorld War II,the Czechoslovak government almost fullyexpelledthem in retaliation for their support ofNazi Germany's invasion and dismemberment of Czechoslovakia (1938–1939) and subsequentGerman war crimes(1938–1945) towards the Czech, Moravian, and Jewish populations.

Moravians

edit-

Comenius

-

Gregor Mendel

-

František Palacký

-

Jaromír Mundy

-

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

-

Leoš Janáček

-

Sigmund Freud

-

Edmund Husserl

-

Alphonse Mucha

-

Adolf Loos

-

Tomáš Baťa

-

Kurt Gödel

-

Emil Zátopek

-

Milan Kundera

-

Ivan Lendl

Notable people from Moravia include (in order of birth):

- Anton Pilgram(1450–1516), architect, sculptor and woodcarver

- Jan Ámos Komenský(Comenius) (1592–1670), educator and theologian, last bishop ofUnity of the Brethren

- Georg Joseph Camellus(1661–1706),Jesuitmissionary to thePhilippines,pharmacist and botanist

- David Zeisberger(1717–1807)Moravianmissionary to theLeni Lenape,"Apostle to the Indians"

- Georgius Prochaska(1749–1820), ophthalmologist and physiologist

- František Palacký(1798–1876), historian and politician, "The Father of theCzech nation"

- Gregor Mendel(1822–1884), founder ofgenetics

- Ernst Mach(1838–1916), physicist and philosopher

- Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk(1850–1937), philosopher and politician, first president of Czechoslovakia

- Leoš Janáček(1854–1928), composer

- Sigmund Freud(1856–1939), founder ofpsychoanalysis

- Edmund Husserl(1859–1938), philosopher

- Alfons Mucha(1860–1939), painter

- Zdeňka Wiedermannová-Motyčková(1868–1915), women's rights activist

- Adolf Loos(1870–1933), architect, pioneer offunctionalism

- Karl Renner(1870–1950), Austrian statesman, co-founder ofFriends of Naturemovement

- Tomáš Baťa(1876–1932), entrepreneur, founder ofBata Shoescompany

- Joseph Schumpeter(1883–1950), economist and political scientist

- Marie Jeritza(1887–1982), soprano singer

- Hans Krebs(1888–1947), Nazi SSBrigadeführerexecuted for treason

- Ludvík Svoboda(1895–1979), general ofI Czechoslovak Army Corps,seventh president of Czechoslovakia

- Klement Gottwald(1896–1953), first Czechoslovakcommunistpresident

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold(1897–1957), composer

- George Placzek(1905–1955), physicist, participant inManhattan Project

- Kurt Gödel(1906–1978), theoretical mathematician

- Oskar Schindler(1908–1974),Nazi Germanyentrepreneur, saviour of almost 1,200 Jews during the WWII

- Jan Kubiš(1913–1942), paratrooper who assassinated NazidespotR. Heydrich

- Bohumil Hrabal(1914–1997), writer

- Thomas J. Bata(1914–2008), entrepreneur, son of Tomáš Baťa and former head of the Bata shoe company

- Emil Zátopek(1922–2000), long-distance runner,multiple Olympic gold medalist

- Karel Reisz(1926–2002), filmmaker, pioneer of the BritishFree Cinemamovement

- Milan Kundera(1929–2023), writer

- Václav Nedomanský(born 1944),ice hockeyplayer

- Karel Kryl(1944–1994), poet and protest singer-songwriter

- Karel Loprais(1949–2021), truck race driver, multiple winner of theDakar Rally

- Ivana Trump(1949–2022), socialite and business magnate, former wife ofDonald Trump

- Ivan Lendl(born 1959),tennisplayer

- Petr Nečas(born 1964), politician,Czech Prime Minister2010–2013

- Paulina Porizkova(born 1965), model, actress, writer

- Jana Novotná(1968–2017), tennis player

- Jiří Šlégr(born 1971),ice hockeyplayer, member of theTriple Gold Club

- Bohuslav Sobotka(born 1971),social-democraticpolitician,Czech Prime Minister2014–2017

- Magdalena Kožená(born 1973), mezzo-soprano

- Markéta Irglová(born 1988),Academy awardedsinger-songwriter

- Petra Kvitová(born 1990), tennis player

- Adam Ondra(born 1993),rock climber

- Barbora Krejčíková(born 1996), tennis player

Ethnographic regions

editMoravia can be divided on dialectal and lore basis into several ethnographic regions of comparable significance. In this sense, it is more heterogenous than Bohemia. Significant parts of Moravia, usually those formerly inhabited by the German speakers, are dialectally indifferent, as they have been resettled by people from various Czech (and Slovak) regions.

The principal cultural regions of Moravia are:

- Hanakia(Haná) in the central and northern part

- Lachia(Lašsko) in the northeastern tip

- Highlands(Horácko) in the west

- Moravian Slovakia(Slovácko) in the southeast

- Moravian Wallachia(Valašsko) in the east

Places of interest

editThis sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(June 2016) |

World Heritage Sites

edit- Gardens and Castle at Kroměříž

- Historic Centre of Telč

- Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc

- Jewish Quarter and St Procopius' Basilica in Třebíč

- Lednice-Valtice Cultural Landscape

- Pilgrimage Church of St John of Nepomuk at Zelená Hora

- Tugendhat Villa in Brno

Other

edit- Hranice Abyss,the deepest known underwater cave in the world

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^Royal Frankish Annals(year 822), pp. 111–112.

- ^Morava, Iniciativa Naša."Fakta o Moravě – Naša Morava".

- ^Bowlus, Charles R. (2009). "Nitra: when did it become a part of the Moravian realm? Evidence in the Frankish sources".Early Medieval Europe.17(3): 311–328.doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00279.x.S2CID161655879.

- ^ab"Encyklopedie dějin města Brna".2004.

- ^ab"Population of municipalities of the Czech Republic, 1 January 2024".Czech Statistical Office.17 May 2024.

- ^"Moravia".LexicoUK English Dictionary.Oxford University Press.Archived fromthe originalon 22 March 2020.;"Moravia".Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.Retrieved22 August2019.

- ^ab"Moravia".Collins English Dictionary.HarperCollins.Retrieved22 August2019.

- ^"Moravia".The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language(5th ed.). HarperCollins.Retrieved22 August2019.

- ^"Dodatek I. Přehled Moravy a Slezska podle žup".Statistický lexikon obcí v republice Československé. Morava a Slezsko(in Czech). Prague: Státní úřad statistický. 1924. p. 133.

- ^"Dodatek IV. Moravské enklávy ve Slezsku".Statistický lexikon obcí v republice Československé. Morava a Slezsko(in Czech). Prague: Státní úřad statistický. 1924. p. 138.

- ^a.s., Economia (18 February 2000)."Jsem Moravan?".

- ^"Říkáte celé ČR Čechy? Pro Moraváky jste ignorant".8 February 2010.

- ^ŠRÁMEK, Rudolf, MAJTÁN, Milan, Lutterer, Ivan: Zeměpisná jména Československa, Mladá fronta (1982), Praha, p. 202.

- ^abAntón, Mauricio; Galobart, Angel; Turner, Alan (May 2005). "Co-existence of scimitar-toothed cats, lions and hominins in the European Pleistocene. Implications of the post-cranial anatomy of Homotherium latidens (Owen) for comparative palaeoecology".Quaternary Science Reviews.24(10–11): 1287–1301.Bibcode:2005QSRv...24.1287A.doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.09.008.

- ^Administrator."About the multipurpose water corridor Danube-Oder-Elbe".Archived fromthe originalon 17 May 2016.Retrieved26 June2016.

- ^Klimo, Emil; Hager, Herbert (2000).The Floodplain Forests in Europe: Current Situation and Perspectives (European Forest Institute research reports).Leiden: Brill. p. 48.ISBN9789004119581.

- ^Velemínskáa, J.; Brůžekb, J.; Velemínskýd, P.; Bigonia, L.; Šefčákováe, A.; Katinaf, F. (2008). "Variability of the Upper Palaeolithic skulls from Předmostí near Přerov (Czech Republic): Craniometric comparison with recent human standards".Homo.59(1): 1–26.doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2007.12.003.PMID18242606.

- ^Viegas, Jennifer (7 October 2011)."Prehistoric dog found with mammoth bone in mouth".Discovery News. Archived fromthe originalon 9 November 2012.Retrieved11 October2011.

- ^Jonathan Jones: Carl Andre on notoriety and a 26,000-year-old portrait – the week in art.The Guardian25 January 2013

- ^"Dolni Vestonice and Pavlov sites".

- ^Oldest homes were made of mammoth bone.The Times29.8.2005

- ^"Detašované pracoviště Dolní Dunajovice – Hradisko u Mušova".

- ^"Opevnění – Detašované pracoviště Dolní Dunajovice, AÚ AV ČR Brno, v. v. i."

- ^Hanel, Norbert; Cerdán, Ángel Morillo; Hernández, Esperanza Martín (1 January 2009).Limes XX: Estudios sobre la frontera romana (Roman frontier studies).Editorial CSIC – CSIC Press.ISBN9788400088545– via Google Books.

- ^"Lázeňská a obytná budova – Detašované pracoviště Dolní Dunajovice, AÚ AV ČR Brno, v. v. i."

- ^Florin Kurta.The history and archaeology of Great Moravia: an introduction.in: "Early Medieval Europe", 2009 volume 17 (3)

- ^Reuter, Timothy. (1991).Germany in the Early Middle Ages,London: Longman, page 82

- ^Štefan, Ivo (2011)."Great Moravia, Statehood and Archaeology: The" Decline and Fall "of One Early Medieval Polity".In Macháček, Jiří; Ungerman, Šimon (eds.).Frühgeschichtliche Zentralorte in Mitteleuropa.Bonn: Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt. pp. 333–354.ISBN978-3-7749-3730-7.Retrieved27 August2013.

- ^Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan (2006).Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe.Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers.ISBN978-0-86516-426-0.

- ^The exact dating of the conquest of Moravia by Bohemian dukes is uncertain. Czech and some Slovak historiographers suggest the year 1019, while Polish, German and other Slovak historians suggest 1029, during the rule of Boleslaus' son,Mieszko II Lambert.

- ^There are no primary testimonies about creating a margraviate (march) as distinct political unit

- ^Svoboda, Zbyšek; Fojtík, Pavel; Exner, Petr; Martykán, Jaroslav (2013)."Odborné vexilologické stanovisko k moravské vlajce"(PDF).Vexilologie. Zpravodaj České vexilologické společnosti, o.s. č. 169.Brno: Česká vexilologická společnost. pp. 3319, 3320.

- ^Pícha, František (2013)."Znaky a prapory v kronice Ottokara Štýrského"(PDF).Vexilologie. Zpravodaj České vexilologické společnosti, o.s. č. 169.Brno: Česká vexilologická společnost. pp. 3320–3324.

- ^Evan Rail (23 September 2011). The Castles of Moravia.NYT23.9.2011

- ^Lánové rejstříky (1656–1711)Archived12 March 2012 at theWayback Machine(in Czech)

- ^"CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Moravia".

- ^Czechoslovakia: A Country Study.US Army. 1898. p. 27.

- ^"Moravia | historical region, Europe | Britannica".www.britannica.com.Retrieved26 April2022.

- ^Hans Chmelar:Höhepunkte der österreichischen Auswanderung. Die Auswanderung aus den im Reichsrat vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern in den Jahren 1905–1914.(=Studien zur Geschichte der österreichisch-ungarischen Monarchie.Band 14) Kommission für die Geschichte der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1974,ISBN3-7001-0075-2,p. 109.

- ^"Working Parties".Lamsdorf.com.Archived fromthe originalon 29 October 2020.Retrieved5 November2023.

- ^"Brünn".Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.Retrieved5 November2023.

- ^"Subcamps of KL Gross-Rosen".Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica.Retrieved5 November2023.

- ^Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022).The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV.Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 207, 257, 259.ISBN978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^Bičík, Ivan; Štěpánek, Vít (1994)."Post-war changes of the land-use structure in Bohemia and Moravia: Case study Sudetenland".GeoJournal.32(3): 253–259.doi:10.1007/BF01122117.S2CID189878438.

- ^"Jelínek's 400-Year Tradition of Making Slivovitz Bears Fruit in the U.S."OU Kosher Certification.5 October 2010.

- ^"Leteckou výrobu v Česku čeká v roce 2013 růst. Pomůže modernizace L-410 (Czech aircraft production expected to grow in 2013)".Hospodářské noviny IHNED.2012.ISSN1213-7693.

- ^"AVG Antivirus and Security Software – Contact us".Retrieved4 October2011.

- ^"Kyndryl Client Center, s.r.o."Faculty of Information Technology, Brno University of Technology.Retrieved31 January2024.

- ^"IBM Governmental Programs – Delivery Centre Central Eastern Europe in Brno".IBM.Retrieved4 October2011.

- ^"Honeywell Global Design Center Brno".Honeywell Czech Republic.Archived fromthe originalon 13 September 2011.Retrieved4 October2011.

- ^"Brno".Siemens(in Czech). Archived fromthe originalon 25 April 2012.Retrieved4 October2011.

- ^"Red Hat Europe".Retrieved4 October2011.

- ^"MOTOROLA – Technology Park Brno".Archived fromthe originalon 29 May 2012.Retrieved4 October2011.

- ^univerzita, Masarykova."O projektu".MUNI | RECETOX(in Czech).Retrieved31 January2024.

- ^"Historický lexikon obcí České republiky 1869–2011"(in Czech). Czech Statistical Office. 21 December 2015.

- ^"Results of the 2021 Census - Open data".Public Database(in Czech).Czech Statistical Office.27 March 2021.

- ^Bill Lehane: ČSÚ (Czech statistical office) plays down census disputes – Campaign want to include Moravian language in count (Moravian identity).The Prague Post9.3.2011 20

- ^Kolínková, Eliška (26 December 2008)."Číšník tvoří spisovnou moravštinu".Mladá fronta DNES(in Czech). iDnes.Retrieved7 December2011.

- ^Zemanová, Barbora (12 November 2008)."Moravané tvoří spisovnou moravštinu".Brněnský Deník(in Czech). denik.cz.Retrieved7 December2011.

- ^O spisovné moravštině a jiných "malých" jazycích (Naše řeč 5, ročník 83/2000)(in Czech)

- ^Kolínková, Eliška (30 December 2008)."Amatérský jazykovědec prosazuje moravštinu jako nový jazyk".Mladá fronta DNES(in Czech). iDnes.Retrieved7 December2011.

- ^Robert B. Kaplan; Richard B. Baldauf (1 January 2005).Language Planning and Policy in Europe.Multilingual Matters. pp. 27–.ISBN978-1-85359-813-5.

- ^Tesser, Lynn (14 May 2013).Ethnic Cleansing and the European Union: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Security, Memory and Ethnography.Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 213–.ISBN978-1-137-30877-1.

- ^Ibp, Inc (10 September 2013).Czech Republic Mining Laws and Regulations Handbook - Strategic Information and Basic Laws.Int'l Business Publications. pp. 8–.ISBN978-1-4330-7727-2.

Further reading

edit- The Penny Cyclopaediaof the Society for the Diffusion of Useful...(1877), volume 15. London,Charles Knight.Moravia. pp. 397–398.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica(2003). Chicago, New Delhi, Paris, Seoul, Sydney, Taipei, Tokyo. Volume 8. p. 309. Moravia.ISBN0-85229 961-3.

- Filip, Jan (1964).The Great Moravia exhibition.ČSAV (Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences).

- Galuška, Luděk, Mitáček Jiří, Novotná, Lea (eds.) (2010)Treausures of Moravia: story of historical land.Brno,Moravian Museum.ISBN978-80-7028-371-4.

- National Geographic Society.Wonders of the Ancient World; National Geographic Atlas of Archaeology,Norman Hammond,consultant, Nat'l Geogr. Soc., (multiple staff authors), (Nat'l Geogr., R. H. Donnelley & Sons, Willard, OH), 1994, 1999, Reg or Deluxe Ed., 304 pp. Deluxe ed. photo (p. 248): "Venus,Dolni Věstonice,24,000 B.C. "In section titled:" The Potter's Art ", pp. 246–253.

- Dekan, Jan (1981).Moravia Magna:The Great Moravian Empire, Its Art and Time, Minneapolis: Control Data Arts.ISBN0-89893-084-7.

- Hugh, Agnew (2004).The Czechs and theLands of the Bohemian Crown.Hoower Press,Stanford.ISBN0-8179-4491-5.

- Róna-Tas, András(1999)Hungarians & Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian Historytranslated by Nicholas Bodoczky,Central European University Press,Budapest,ISBN963-9116-48-3.

- Wihoda, Martin (2015),Vladislaus Henry:The Formation of Moravian Identity.Brill PublishersISBN9789004250499.

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (1996)A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for SurvivalSt. Martin's Press,New York,ISBN0-312-16125-5.

- Constantine PorphyrogenitusDe Administrando Imperioedited by Gy. Moravcsik, translated byR. J. H. Jenkins,Dumbarton Oaks Edition, Washington, D.C. (1993)

- Hlobil, Ivo, Daniel, Ladislav (2000),The last flowers of the middle ages: from the gothic to the renaissance in Moravia and Silesia.Olomouc/Brno,Moravian Galery,Muzeum umění OlomoucISBN9788085227406

- David, Jiří (2009). "Moravian estatism and provincial councils in the second half of the 17th century".Folia historica Bohemica. 1 24: 111–165.ISSN0231-7494.

- Svoboda, Jiří A. (1999),Hunters between East and West: the paleolithic of Moravia.New York: Plenum Press,ISSN0231-7494.

- Absolon, Karel (1949),The diluvial anthropomorphic statuettes and drawings, especially the so-called Venus statuettes, discovered in MoraviaNew York, Salmony 1949.ISSN0231-7494.

- Musil, Rudolf (1971),G. Mendel's Discovery and the Development of Agricultural and Natural Sciences in Moravia.Brno,Moravian Museum.

- Šimsa, Martin (2009),Open-Air Museum of Rural Architecture in South-East Moravia.Strážnice,National Institute of Folk Culture.ISBN9788087261194.

- Miller, Michael R. (2010),The Jews of Moravia in the Age of Emancipation,Cover of Rabbis and Revolution edition. Stanford University Press.ISBN9780804770569.

- Bata, Thomas J.(1990),Bata: Shoemaker to the World.Stoddart Publishers Canada.ISBN9780773724167.

- Knox, Brian (1962),Bohemia and Moravia: An Architectural Companion.Faber & Faber.

External links

edit- Moravské zemské muzeum official website

- Moravian gallery official website

- Moravian library official website

- Moravian land archive official websiteArchived26 October 2016 at theWayback Machine(in Czech)

- Province of Moravia – Czech Catholic Church – official website

- Welcome to the 2nd largest city of the CR(in Czech, English, and German)

- Welcome to Olomouc, city of good cheer...(in Czech, English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Polish, Russian, Japanese, and Chinese)

- Znojmo – City of VirtueArchived8 December 2013 at theWayback Machine(in Czech, English, and German)

- Texts on Wikisource:

- "Moravia".New International Encyclopedia.Vol. XIII. 1905.

- "Moravia".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. XVI (9th ed.). 1883.

- "Moravia".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 18 (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Moravia".Catholic Encyclopedia.Vol. 10. 1911.