TheNotch signaling pathwayis a highlyconservedcell signalingsystem present in mostanimals.[1]Mammals possess four differentnotch receptors,referred to asNOTCH1,NOTCH2,NOTCH3,andNOTCH4.[2]The notch receptor is a single-passtransmembrane receptorprotein. It is ahetero-oligomercomposed of a largeextracellularportion, which associates in acalcium-dependent,non-covalentinteraction with a smaller piece of the notch protein composed of a short extracellular region, a single transmembrane-pass, and a smallintracellularregion.[3]

Notch signaling promotes proliferative signaling duringneurogenesis,and its activity is inhibited byNumbto promote neural differentiation. It plays a major role in the regulation of embryonic development.

Notch signaling is dysregulated in many cancers, and faulty notch signaling is implicated in many diseases, including T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL),[4]cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with sub-cortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), multiple sclerosis,Tetralogy of Fallot,andAlagille syndrome.Inhibition of notch signaling inhibits the proliferation of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in both cultured cells and a mouse model.[5][6]

Discovery

editIn 1914, John S. Dexter noticed the appearance of a notch in the wings of the fruit flyDrosophila melanogaster.Theallelesof the gene were identified in 1917 by American evolutionary biologistThomas Hunt Morgan.[7][8]Its molecular analysis and sequencing was independently undertaken in the 1980s bySpyros Artavanis-TsakonasandMichael W. Young.[9][10]Alleles of the twoC. elegansNotchgenes were identified based on developmental phenotypes:lin-12[11]andglp-1.[12][13]The cloning and partial sequence oflin-12was reported at the same time asDrosophilaNotchby Iva Greenwald.[14]

Mechanism

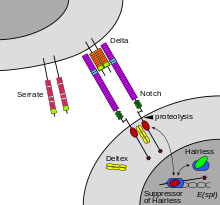

editTheNotch proteinspans thecell membrane,with part of it inside and part outside.Ligandproteins binding to the extracellular domain induce proteolytic cleavage and release of the intracellular domain, which enters thecell nucleusto modifygene expression.[15]

The cleavage model was first proposed in 1993 based on work done withDrosophilaNotchandC. eleganslin-12,[16][17]informed by the first oncogenic mutation affecting a humanNotchgene.[18]Compelling evidence for this model was provided in 1998 by in vivo analysis inDrosophilaby Gary Struhl[19]and in cell culture by Raphael Kopan.[20]Although this model was initially disputed,[1]the evidence in favor of the model was irrefutable by 2001.[21][22]

The receptor is normally triggered via direct cell-to-cell contact, in which the transmembrane proteins of the cells in direct contact form the ligands that bind the notch receptor. The Notch binding allows groups of cells to organize themselves such that, if one cell expresses a given trait, this may be switched off in neighbouring cells by the intercellular notch signal. In this way, groups of cells influence one another to make large structures. Thus, lateral inhibition mechanisms are key to Notch signaling.lin-12andNotchmediate binary cell fate decisions, and lateral inhibition involves feedback mechanisms to amplify initial differences.[21]

TheNotch cascadeconsists of Notch and Notchligands,as well as intracellular proteins transmitting the notch signal to the cell's nucleus. The Notch/Lin-12/Glp-1 receptor family[23]was found to be involved in the specification of cell fates during development inDrosophilaandC. elegans.[24]

The intracellular domain of Notch forms a complex withCBF1andMastermindto activate transcription of target genes. The structure of the complex has been determined.[25][26]

Pathway

editMaturation of the notch receptor involves cleavage at the prospective extracellular side during intracellular trafficking in the Golgi complex.[27]This results in a bipartite protein, composed of a large extracellular domain linked to the smaller transmembrane and intracellular domain. Binding of ligand promotes two proteolytic processing events; as a result of proteolysis, the intracellular domain is liberated and can enter the nucleus to engage other DNA-binding proteins and regulate gene expression.

Notch and most of its ligands are transmembrane proteins, so the cells expressing the ligands typically must be adjacent to the notch expressing cell for signaling to occur.[citation needed]The notch ligands are also single-pass transmembrane proteins and are members of the DSL (Delta/Serrate/LAG-2) family of proteins. InDrosophila melanogaster(the fruit fly), there are two ligands namedDeltaandSerrate.In mammals, the corresponding names areDelta-likeandJagged.In mammals there are multiple Delta-like and Jagged ligands, as well as possibly a variety of other ligands, such as F3/contactin.[28]

In the nematodeC. elegans,two genes encode homologous proteins,glp-1andlin-12.There has been at least one report that suggests that some cells can send out processes that allow signaling to occur between cells that are as much as four or five cell diameters apart.[citation needed]

The notch extracellular domain is composed primarily of small cystine-rich motifs calledEGF-like repeats.[29]

Notch 1, for example, has 36 of these repeats. Each EGF-like repeat is composed of approximately 40 amino acids, and its structure is defined largely by six conserved cysteine residues that form three conserved disulfide bonds. Each EGF-like repeat can be modified byO-linked glycansat specific sites.[30]AnO-glucosesugar may be added between the first and second conserved cysteines, and anO-fucosemay be added between the second and third conserved cysteines. These sugars are added by an as-yet-unidentifiedO-glucosyltransferase(except forRumi), andGDP-fucose ProteinO-fucosyltransferase 1(POFUT1), respectively. The addition ofO-fucosebyPOFUT1is absolutely necessary for notch function, and, without the enzyme to addO-fucose, all notch proteins fail to function properly. As yet, the manner by which the glycosylation of notch affects function is not completely understood.

TheO-glucose on notch can be further elongated to a trisaccharide with the addition of twoxylosesugars byxylosyltransferases,and theO-fucosecan be elongated to a tetrasaccharide by the ordered addition of anN-acetylglucosamine(GlcNAc) sugar by anN-AcetylglucosaminyltransferasecalledFringe,the addition of agalactoseby agalactosyltransferase,and the addition of asialic acidby asialyltransferase.[31]

To add another level of complexity, in mammals there are three Fringe GlcNAc-transferases, named lunatic fringe, manic fringe, and radical fringe. These enzymes are responsible for something called a "fringe effect" on notch signaling.[32]If Fringe adds a GlcNAc to theO-fucosesugar then the subsequent addition of a galactose and sialic acid will occur. In the presence of this tetrasaccharide, notch signals strongly when it interacts with the Delta ligand, but has markedly inhibited signaling when interacting with the Jagged ligand.[33]The means by which this addition of sugar inhibits signaling through one ligand, and potentiates signaling through another is not clearly understood.

Once the notch extracellular domain interacts with a ligand, an ADAM-familymetalloproteasecalled ADAM10, cleaves the notch protein just outside the membrane.[34]This releases the extracellular portion of notch (NECD), which continues to interact with the ligand. The ligand plus the notch extracellular domain is thenendocytosedby the ligand-expressing cell. There may be signaling effects in the ligand-expressing cell after endocytosis; this part of notch signaling is a topic of active research.[citation needed]After this first cleavage, an enzyme calledγ-secretase(which is implicated inAlzheimer's disease) cleaves the remaining part of the notch protein just inside the inner leaflet of thecell membraneof the notch-expressing cell. This releases the intracellular domain of the notch protein (NICD), which then moves to thenucleus,where it can regulate gene expression by activating thetranscription factorCSL.It was originally thought that these CSL proteins suppressed Notch target transcription. However, further research showed that, when the intracellular domain binds to the complex, it switches from a repressor to an activator of transcription.[35]Other proteins also participate in the intracellular portion of the notch signaling cascade.[36]

Ligand interactions

editNotch signaling is initiated when Notch receptors on the cell surface engage ligands presentedin transon opposing cells.Despite the expansive size of the Notch extracellular domain, it has been demonstrated that EGF domains 11 and 12 are the critical determinants for interactions with Delta.[37]Additional studies have implicated regions outside of Notch EGF11-12 in ligand binding. For example, Notch EGF domain 8 plays a role in selective recognition of Serrate/Jagged[38]and EGF domains 6-15 are required for maximal signaling upon ligand stimulation.[39]A crystal structure of the interacting regions of Notch1 and Delta-like 4 (Dll4) provided a molecular-level visualization of Notch-ligand interactions, and revealed that the N-terminal MNNL (or C2) and DSL domains of ligands bind to Notch EGF domains 12 and 11, respectively.[40]The Notch1-Dll4 structure also illuminated a direct role for Notch O-linked fucose and glucose moieties in ligand recognition, and rationalized a structural mechanism for the glycan-mediated tuning of Notch signaling.[40]

Synthetic Notch signaling

editIt is possible to engineer synthetic Notch receptors by replacing the extracellular receptor and intracellular transcriptional domains with other domains of choice. This allows researchers to select which ligands are detected, and which genes are upregulated in response. Using this technology, cells can report or change their behavior in response to contact with user-specified signals, facilitating new avenues of both basic and applied research into cell-cell signaling.[41]Notably, this system allows multiple synthetic pathways to be engineered into a cell in parallel.[42][43]

Function

editThe Notch signaling pathway is important for cell-cell communication, which involves gene regulation mechanisms that control multiple cell differentiation processes during embryonic and adult life. Notch signaling also has a role in the following processes:

- neuronalfunction and development[44][45][46][47]

- stabilization of arterial endothelial fate andangiogenesis[48]

- regulation of crucial cell communication events betweenendocardiumandmyocardiumduring both the formation of the valve primordial andventriculardevelopment and differentiation[49]

- cardiac valvehomeostasis,as well as implications in other human disorders involving the cardiovascular system[50]

- timely cell lineage specification of bothendocrineandexocrine pancreas[51]

- influencing of binary fate decisions of cells that must choose between the secretory and absorptive lineages in the gut[52]

- expansion of thehematopoietic stem cellcompartment during bone development and participation in commitment to theosteoblasticlineage, suggesting a potential therapeutic role for notch in bone regeneration and osteoporosis[53]

- expansion of the hemogenic endothelial cells along with signaling axis involvingHedgehog signalingandScl[54]

- T celllineage commitment from common lymphoid precursor[55]

- regulation of cell-fate decision inmammary glandsat several distinct development stages[56]

- possibly some non-nuclear mechanisms, such as control of theactincytoskeletonthrough thetyrosine kinaseAbl[28]

- Regulation of the mitotic/meiotic decision in theC. elegansgermline[12]

- development ofalveoliin thelung.[57]

It has also been found thatRex1has inhibitory effects on the expression of notch inmesenchymal stem cells,preventing differentiation.[58]

Role in embryogenesis

editThe Notch signaling pathway plays an important role in cell-cell communication, and further regulates embryonic development.

Embryo polarity

editNotch signaling is required in the regulation of polarity. For example, mutation experiments have shown that loss of Notch signaling causes abnormal anterior-posterior polarity insomites.[59]Also, Notch signaling is required during left-right asymmetry determination in vertebrates.[60]

Early studies in thenematodemodel organismC. elegansindicate that Notch signaling has a major role in the induction of mesoderm and cell fate determination.[12]As mentioned previously, C. elegans has two genes that encode for partially functionally redundant Notch homologs,glp-1andlin-12.[61]During C. elegans, GLP-1, the C. elegans Notch homolog, interacts with APX-1, the C. elegans Delta homolog. This signaling between particular blastomeres induces differentiation of cell fates and establishes the dorsal-ventral axis.[62]

Role in somitogenesis

edit

Notch signaling is central tosomitogenesis.In 1995, Notch1 was shown to be important for coordinating the segmentation of somites in mice.[63]Further studies identified the role of Notch signaling in the segmentation clock. These studies hypothesized that the primary function of Notch signaling does not act on an individual cell, but coordinates cell clocks and keep them synchronized. This hypothesis explained the role of Notch signaling in the development of segmentation and has been supported by experiments in mice and zebrafish.[64][65][66]Experiments with Delta1 mutant mice that show abnormal somitogenesis with loss of anterior/posterior polarity suggest that Notch signaling is also necessary for the maintenance of somite borders.[63]

Duringsomitogenesis,a molecular oscillator inparaxial mesodermcells dictates the precise rate of somite formation. Aclock and wavefront modelhas been proposed in order to spatially determine the location and boundaries betweensomites.This process is highly regulated as somites must have the correct size and spacing in order to avoid malformations within the axial skeleton that may potentially lead tospondylocostal dysostosis.Several key components of the Notch signaling pathway help coordinate key steps in this process. In mice, mutations in Notch1, Dll1 or Dll3, Lfng, or Hes7 result in abnormal somite formation. Similarly, in humans, the following mutations have been seen to lead to development of spondylocostal dysostosis: DLL3, LFNG, or HES7.[67]

Role in epidermal differentiation

editNotch signaling is known to occur inside ciliated, differentiating cells found in the first epidermal layers during early skin development.[68]Furthermore, it has found thatpresenilin-2works in conjunction with ARF4 to regulate Notch signaling during this development.[69]However, it remains to be determined whether gamma-secretase has a direct or indirect role in modulating Notch signaling.

Role in central nervous system development and function

editEarly findings on Notch signaling incentral nervous system(CNS) development were performed mainly inDrosophilawithmutagenesisexperiments. For example, the finding that an embryonic lethal phenotype inDrosophilawas associated with Notch dysfunction[70]indicated that Notch mutations can lead to the failure of neural andEpidermalcell segregation in earlyDrosophilaembryos. In the past decade, advances in mutation and knockout techniques allowed research on the Notch signaling pathway in mammalian models, especially rodents.

The Notch signaling pathway was found to be critical mainly for neuralprogenitor cell(NPC) maintenance and self-renewal. In recent years, other functions of the Notch pathway have also been found, includingglial cellspecification,[71][72]neuritesdevelopment,[73]as well as learning and memory.[74]

Neuron cell differentiation

editThe Notch pathway is essential for maintaining NPCs in the developing brain. Activation of the pathway is sufficient to maintain NPCs in a proliferating state, whereas loss-of-function mutations in the critical components of the pathway cause precocious neuronal differentiation and NPC depletion.[45]Modulators of the Notch signal, e.g., theNumbprotein are able to antagonize Notch effects, resulting in the halting of cell cycle and the differentiation of NPCs.[75][76]Conversely, thefibroblast growth factorpathway promotes Notch signaling to keepstem cellsof thecerebral cortexin the proliferative state, amounting to a mechanism regulating cortical surface area growth and, potentially,gyrification.[77][78]In this way, Notch signaling controls NPC self-renewal as well as cell fate specification.

A non-canonical branch of the Notch signaling pathway that involves the phosphorylation of STAT3 on the serine residue at amino acid position 727 and subsequent Hes3 expression increase (STAT3-Ser/Hes3 Signaling Axis) has been shown to regulate the number of NPCs in culture and in the adult rodent brain.[79]

In adult rodents and in cell culture, Notch3 promotes neuronal differentiation, having a role opposite to Notch1/2.[80]This indicates that individual Notch receptors can have divergent functions, depending on cellular context.

Neurite development

editIn vitrostudies show that Notch can influenceneuritedevelopment.[73]In vivo,deletion of the Notch signaling modulator, Numb, disrupts neuronal maturation in the developing cerebellum,[81]whereas deletion of Numb disrupts axonal arborization in sensory ganglia.[82]Although the mechanism underlying this phenomenon is not clear, together these findings suggest Notch signaling might be crucial in neuronal maturation.

Gliogenesis

editIngliogenesis,Notch appears to have an instructive role that can directly promote the differentiation of manyglial cellsubtypes.[71][72]For example, activation of Notch signaling in the retina favors the generation ofMuller gliacells at the expense of neurons, whereas reduced Notch signaling induces production of ganglion cells, causing a reduction in the number of Muller glia.[45]

Adult brain function

editApart from its role in development, evidence shows that Notch signaling is also involved in neuronal apoptosis, neurite retraction, and neurodegeneration of ischemic stroke in the brain[83]In addition to developmental functions, Notch proteins and ligands are expressed in cells of the adult nervous system,[84]suggesting a role in CNS plasticity throughout life. Adult mice heterozygous for mutations in either Notch1 or Cbf1 have deficits in spatial learning and memory.[74]Similar results are seen in experiments withpresenilins1 and 2, which mediate the Notch intramembranous cleavage. To be specific, conditional deletion of presenilins at 3 weeks after birth in excitatory neurons causes learning and memory deficits, neuronal dysfunction, and gradual neurodegeneration.[85]Severalgamma secretaseinhibitors that underwent human clinical trials inAlzheimer's diseaseandMCIpatients resulted in statistically significant worsening of cognition relative to controls, which is thought to be due to its incidental effect on Notch signalling.[86]

Role in cardiovascular development

editThe Notch signaling pathway is a critical component of cardiovascular formation andmorphogenesisin both development and disease. It is required for the selection of endothelialtipandstalk cellsduringsprouting angiogenesis.[87]

Cardiac development

editNotch signal pathway plays a crucial role in at least three cardiac development processes:Atrioventricular canaldevelopment,myocardial development,and cardiac outflow tract (OFT) development.[88]

Atrioventricular (AV) canal development

edit- AV boundary formation

- Notch signaling can regulate the atrioventricular boundary formation between the AV canal and the chamber myocardium.

Studies have revealed that both loss- and gain-of-function of the Notch pathway results in defects in AV canal development.[88]In addition, the Notch target genesHEY1andHEY2are involved in restricting the expression of two critical developmental regulator proteins, BMP2 and Tbx2, to the AV canal.[89][90]

- AV epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

- Notch signaling is also important for the process of AVEMT,which is required for AV canal maturation. After the AV canal boundary formation, a subset of endocardial cells lining the AV canal are activated by signals emanating from themyocardiumand by interendocardial signaling pathways to undergo EMT.[88]Notch1 deficiency results in defective induction of EMT. Very few migrating cells are seen and these lack mesenchymal morphology.[91]Notch may regulate this process by activating matrixmetalloproteinase2 (MMP2) expression, or by inhibitingvascular endothelial (VE)-cadherinexpression in the AV canal endocardium[92]while suppressing the VEGF pathway via VEGFR2.[93]In RBPJk/CBF1-targeted mutants, the heart valve development is severely disrupted, presumably because of defective endocardial maturation and signaling.[91]

Ventricular development

editSome studies inXenopus[94]and in mouse embryonic stem cells[95]indicate that cardiomyogenic commitment and differentiation require Notch signaling inhibition. Active Notch signaling is required in the ventricularendocardiumfor proper trabeculae development subsequent to myocardial specification by regulatingBMP10,NRG1,andEphrinB2 expression.[49]Notch signaling sustains immaturecardiomyocyte proliferationin mammals[96][97][98]and zebrafish.[99]A regulatory correspondence likely exists between Notch signaling andWnt signaling,whereby upregulated Wnt expression downregulates Notch signaling, and a subsequent inhibition of ventricular cardiomyocyte proliferation results. This proliferative arrest can be rescued using Wnt inhibitors.[100]

The downstream effector of Notch signaling, HEY2, was also demonstrated to be important in regulating ventricular development by its expression in the interventricularseptumand the endocardial cells of thecardiac cushions.[101]Cardiomyocyte and smooth muscle cell-specific deletion of HEY2 results in impaired cardiac contractility, malformed right ventricle, and ventricular septal defects.[102]

Ventricular outflow tract development

editDuring development of the aortic arch and the aortic arch arteries, the Notch receptors, ligands, and target genes display a unique expression pattern.[103]When the Notch pathway was blocked, the induction of vascularsmooth musclecell marker expression failed to occur, suggesting that Notch is involved in the differentiation of cardiac neural crest cells into vascular cells during outflow tract development.

Angiogenesis

editEndothelialcells use the Notch signaling pathway to coordinate cellular behaviors during the blood vessel sprouting that occurssprouting angiogenesis.[104][105][106][107]

Activation of Notch takes place primarily in "connector" cells and cells that line patent stable blood vessels through direct interaction with the Notch ligand,Delta-like ligand 4(Dll4), which is expressed in the endothelial tip cells.[108]VEGF signaling, which is an important factor for migration and proliferation of endothelial cells,[109]can be downregulated in cells with activated Notch signaling by lowering the levels of Vegf receptor transcript.[110]Zebrafish embryos lacking Notch signaling exhibit ectopic and persistent expression of the zebrafish ortholog of VEGF3, flt4, within all endothelial cells, while Notch activation completely represses its expression.[111]

Notch signaling may be used to control the sprouting pattern of blood vessels during angiogenesis. When cells within a patent vessel are exposed toVEGFsignaling, only a restricted number of them initiate the angiogenic process. Vegf is able to induceDLL4expression. In turn, DLL4 expressing cells down-regulate Vegf receptors in neighboring cells through activation of Notch, thereby preventing their migration into the developing sprout. Likewise, during the sprouting process itself, the migratory behavior of connector cells must be limited to retain a patent connection to the original blood vessel.[108]

Role in endocrine development

editDuring development, definitiveendodermandectodermdifferentiates into several gastrointestinal epithelial lineages, including endocrine cells. Many studies have indicated that Notch signaling has a major role in endocrine development.

Pancreatic development

editThe formation of the pancreas from endoderm begins in early development. The expression of elements of the Notch signaling pathway have been found in the developing pancreas, suggesting that Notch signaling is important in pancreatic development.[112][113]Evidence suggests Notch signaling regulates the progressive recruitment of endocrine cell types from a common precursor,[114]acting through two possible mechanisms. One is the "lateral inhibition", which specifies some cells for a primary fate but others for a secondary fate among cells that have the potential to adopt the same fate. Lateral inhibition is required for many types of cell fate determination. Here, it could explain the dispersed distribution of endocrine cells within pancreatic epithelium.[115]A second mechanism is "suppressive maintenance", which explains the role of Notch signaling in pancreas differentiation. Fibroblast growth factor10 is thought to be important in this activity, but the details are unclear.[116][117]

Intestinal development

editThe role of Notch signaling in the regulation of gut development has been indicated in several reports. Mutations in elements of the Notch signaling pathway affect the earliest intestinal cell fate decisions during zebrafish development.[118]Transcriptional analysis and gain of function experiments revealed that Notch signaling targets Hes1 in the intestine and regulates a binary cell fate decision between adsorptive and secretory cell fates.[118]

Bone development

editEarlyin vitrostudies have found the Notch signaling pathway functions as down-regulator inosteoclastogenesisandosteoblastogenesis.[119]Notch1 is expressed in the mesenchymal condensation area and subsequently in the hypertrophicchondrocytesduring chondrogenesis.[120]Overexpression of Notch signaling inhibits bone morphogenetic protein2-induced osteoblast differentiation. Overall, Notch signaling has a major role in the commitment of mesenchymal cells to the osteoblastic lineage and provides a possible therapeutic approach to bone regeneration.[53]

Role in cancer

editLeukemia

editAberrant Notch signaling is a driver of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL)[121]and is mutated in at least 65% of all T-ALL cases.[122]Notch signaling can be activated by mutations in Notch itself, inactivating mutations inFBXW7(a negative regulator of Notch1), or rarely by t(7;9)(q34;q34.3) translocation. In the context of T-ALL, Notch activity cooperates with additional oncogenic lesions such asc-MYCto activate anabolic pathways such as ribosome and protein biosynthesis thereby promoting leukemia cell growth.[123]

Urothelial bladder cancer

editLoss of Notch activity is a driving event in urothelial cancer. A study identified inactivating mutations in components of the Notch pathway in over 40% of examined human bladder carcinomas. In mouse models, genetic inactivation of Notch signaling results in Erk1/2 phosphorylation leading to tumorigenesis in the urinary tract.[124]As not all NOTCH receptors are equally involved in the urothelial bladder cancer, 90% of samples in one study had some level of NOTCH3 expression, suggesting that NOTCH3 plays an important role in urothelial bladder cancer. A higher level of NOTCH3 expression was observed in high-grade tumors, and a higher level of positivity was associated with a higher mortality risk. NOTCH3 was identified as an independent predictor of poor outcome. Therefore, it is suggested that NOTCH3 could be used as a marker for urothelial bladder cancer-specific mortality risk. It was also shown that NOTCH3 expression could be a prognostic immunohistochemical marker for clinical follow-up of urothelial bladder cancer patients, contributing to a more individualized approach by selecting patients to undergo control cystoscopy after a shorter time interval.[125]

Liver cancer

editInhepatocellular carcinoma,for instance, it was suggesting thatAXIN1mutations would provoke Notch signaling pathway activation, fostering the cancer development, but a recent study demonstrated that such an effect cannot be detected.[126]Thus the exact role of Notch signaling in the cancer process awaits further elucidation.

Notch inhibitors

editThe involvement of Notch signaling in many cancers has led to investigation ofnotch inhibitors(especiallygamma-secretase inhibitors) as cancer treatments which are in different phases of clinical trials.[2][127]As of 2013[update]at least 7 notch inhibitors were in clinical trials.[128]MK-0752has given promising results in an early clinical trial for breast cancer.[129]Preclinical studies showed beneficial effects ofgamma-secretaseinhibitors inendometriosis,[130]a disease characterised by increased expression of notch pathway constituents.[131][132]Several notch inhibitors, including the gamma-secretase inhibitorLY3056480,are being studied for their potential ability to regeneratehair cellsin thecochlea,which could lead to treatments forhearing lossandtinnitus.[133][134]

Mathematical modeling

editMathematical modeling in Notch-Delta signaling has become a pivotal tool in understanding pattern formation driven by cell-cell interactions, particularly in the context of lateral-inhibition mechanisms. The Collier model,[135]a cornerstone in this field, employs a system of coupledordinary differential equationsto describe the feedback loop between adjacent cells. The model is defined by the equations:

whereandrepresent the levels ofNotchand Delta activity in cell,respectively. Functionsandare typicallyHill functions,reflecting the regulatory dynamics of the signaling process. The termdenotes the average level of Delta activity in the cells adjacent to cell,integratingjuxtacrine signalingeffects.

Recent extensions of this model incorporate long-range signaling, acknowledging the role of cell protrusions likefilopodia(cytonemes) that reach non-neighboring cells.[136][137][138][139]One extended model, often referred to as the-Collier model,[136]introduces a weighting parameterto balance juxtacrine and long-range signaling. The interaction termis modified to include these protrusions, creating a more complex, non-local signaling network. This model is instrumental in exploring pattern formation robustness and biological pattern refinement, considering the stochastic nature of filopodia dynamics and intrinsic noise. The application of mathematical modeling in Notch-Delta signaling has been particularly illuminating in understanding the patterning of sensory organ precursors (SOPs) in theDrosophila's notum andwing margin.[140][141]

The mathematical modeling of Notch-Delta signaling thus provides significant insights into lateral inhibition mechanisms and pattern formation in biological systems. It enhances the understanding of cell-cell interaction variations leading to diverse tissue structures, contributing to developmental biology and offering potential therapeutic pathways in diseases related to Notch-Delta dysregulation.

See also

edit- Alagille syndrome

- Netpath– A curated resource of signal transduction pathways in humans

References

edit- ^abArtavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ (April 1999). "Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development".Science.284(5415): 770–776.Bibcode:1999Sci...284..770A.doi:10.1126/science.284.5415.770.PMID10221902.

- ^abKumar R, Juillerat-Jeanneret L, Golshayan D (September 2016)."Notch Antagonists: Potential Modulators of Cancer and Inflammatory Diseases".Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.59(17): 7719–7737.doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01516.PMID27045975.S2CID43654713.

- ^Brou C, Logeat F, Gupta N, Bessia C, LeBail O, Doedens JR, et al. (February 2000)."A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE".Molecular Cell.5(2): 207–216.doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80417-7.PMID10882063.

- ^Sharma VM, Draheim KM, Kelliher MA (April 2007)."The Notch1/c-Myc pathway in T cell leukemia".Cell Cycle.6(8): 927–930.doi:10.4161/cc.6.8.4134.PMID17404512.

- ^Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, et al. (November 2009)."Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex".Nature.462(7270): 182–188.Bibcode:2009Natur.462..182M.doi:10.1038/nature08543.PMC2951323.PMID19907488.

- ^Arora PS, Ansari AZ (November 2009)."Chemical biology: A Notch above other inhibitors".Nature.462(7270): 171–173.Bibcode:2009Natur.462..171A.doi:10.1038/462171a.PMID19907487.S2CID205050842.

- ^Morgan TH(1917)."The theory of the gene".The American Naturalist.51(609): 513–544.doi:10.1086/279629.S2CID84050307.

- ^Morgan TH (1928).The theory of the gene(revised ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 77–81.ISBN978-0-8240-1384-4.

- ^Wharton KA, Johansen KM, Xu T, Artavanis-Tsakonas S (December 1985)."Nucleotide sequence from the neurogenic locus notch implies a gene product that shares homology with proteins containing EGF-like repeats".Cell.43(3 Pt 2): 567–581.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(85)90229-6.PMID3935325.

- ^Kidd S, Kelley MR, Young MW (September 1986)."Sequence of the notch locus of Drosophila melanogaster: relationship of the encoded protein to mammalian clotting and growth factors".Molecular and Cellular Biology.6(9): 3094–3108.doi:10.1128/mcb.6.9.3094.PMC367044.PMID3097517.

- ^Greenwald IS, Sternberg PW, Horvitz HR (September 1983). "The lin-12 locus specifies cell fates in Caenorhabditis elegans".Cell.34(2): 435–444.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90377-x.PMID6616618.S2CID40668388.

- ^abcAustin J, Kimble J (November 1987). "glp-1 is required in the germ line for regulation of the decision between mitosis and meiosis in C. elegans".Cell.51(4): 589–599.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90128-0.PMID3677168.S2CID31484517.

- ^Priess JR, Schnabel H, Schnabel R (November 1987). "The glp-1 locus and cellular interactions in early C. elegans embryos".Cell.51(4): 601–611.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90129-2.PMID3677169.S2CID6282210.

- ^Greenwald I (December 1985)."lin-12, a nematode homeotic gene, is homologous to a set of mammalian proteins that includes epidermal growth factor".Cell.43(3 Pt 2): 583–590.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(85)90230-2.PMID3000611.

- ^Oswald F, Täuber B, Dobner T, Bourteele S, Kostezka U, Adler G, et al. (November 2001)."p300 acts as a transcriptional coactivator for mammalian Notch-1".Molecular and Cellular Biology.21(22): 7761–7774.doi:10.1128/MCB.21.22.7761-7774.2001.PMC99946.PMID11604511.

- ^Lieber T, Kidd S, Alcamo E, Corbin V, Young MW (October 1993)."Antineurogenic phenotypes induced by truncated Notch proteins indicate a role in signal transduction and may point to a novel function for Notch in nuclei".Genes & Development.7(10): 1949–1965.doi:10.1101/gad.7.10.1949.PMID8406001.

- ^Struhl G, Fitzgerald K, Greenwald I (July 1993). "Intrinsic activity of the Lin-12 and Notch intracellular domains in vivo".Cell.74(2): 331–345.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90424-O.PMID8343960.S2CID27966283.

- ^Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, Soreng AL, Reynolds TC, Smith SD, Sklar J (August 1991). "TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms".Cell.66(4): 649–661.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-B.PMID1831692.S2CID45604279.

- ^Struhl G, Adachi A (May 1998)."Nuclear access and action of notch in vivo".Cell.93(4): 649–660.doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81193-9.PMID9604939.S2CID10828910.

- ^Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R (May 1998). "Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain".Nature.393(6683): 382–386.Bibcode:1998Natur.393..382S.doi:10.1038/30756.PMID9620803.S2CID4431882.

- ^abGreenwald I (July 2012)."Notch and the awesome power of genetics".Genetics.191(3): 655–669.doi:10.1534/genetics.112.141812.PMC3389966.PMID22785620.

- ^Struhl G, Greenwald I (January 2001)."Presenilin-mediated transmembrane cleavage is required for Notch signal transduction in Drosophila".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.98(1): 229–234.Bibcode:2001PNAS...98..229S.doi:10.1073/pnas.98.1.229.PMC14573.PMID11134525.

- ^Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Matsuno K, Fortini ME (April 1995). "Notch signaling".Science.268(5208): 225–232.Bibcode:1995Sci...268..225A.doi:10.1126/science.7716513.PMID7716513.

- ^Singson A, Mercer KB, L'Hernault SW (April 1998)."The C. elegans spe-9 gene encodes a sperm transmembrane protein that contains EGF-like repeats and is required for fertilization".Cell.93(1): 71–79.doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81147-2.PMID9546393.S2CID17455442.

- ^Nam Y, Sliz P, Song L, Aster JC,Blacklow SC(March 2006)."Structural basis for cooperativity in recruitment of MAML coactivators to Notch transcription complexes".Cell.124(5): 973–983.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.037.PMID16530044.S2CID17809522.

- ^Wilson JJ, Kovall RA (March 2006)."Crystal structure of the CSL-Notch-Mastermind ternary complex bound to DNA".Cell.124(5): 985–996.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.035.PMID16530045.S2CID9224353.

- ^Munro S, Freeman M (July 2000)."The notch signalling regulator fringe acts in the Golgi apparatus and requires the glycosyltransferase signature motif DXD".Current Biology.10(14): 813–820.Bibcode:2000CBio...10..813M.doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00578-9.PMID10899003.S2CID13909969.

- ^abLai EC (March 2004). "Notch signaling: control of cell communication and cell fate".Development.131(5): 965–973.doi:10.1242/dev.01074.PMID14973298.S2CID6930563.

- ^Ma B, Simala-Grant JL, Taylor DE (December 2006). "Fucosylation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes".Glycobiology.16(12): 158R–184R.doi:10.1093/glycob/cwl040.PMID16973733.

- ^Shao L, Luo Y, Moloney DJ, Haltiwanger R (November 2002). "O-glycosylation of EGF repeats: identification and initial characterization of a UDP-glucose: protein O-glucosyltransferase".Glycobiology.12(11): 763–770.doi:10.1093/glycob/cwf085.PMID12460944.

- ^Lu L, Stanley P (2006). "Roles of O-Fucose Glycans in Notch Signaling Revealed by Mutant Mice".Functional Glycomics.Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 417. pp. 127–136.doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(06)17010-X.ISBN9780121828226.PMID17132502.

- ^Thomas GB, van Meyel DJ (February 2007)."The glycosyltransferase Fringe promotes Delta-Notch signaling between neurons and glia, and is required for subtype-specific glial gene expression".Development.134(3): 591–600.doi:10.1242/dev.02754.PMID17215308.

- ^LaVoie MJ, Selkoe DJ (September 2003)."The Notch ligands, Jagged and Delta, are sequentially processed by alpha-secretase and presenilin/gamma-secretase and release signaling fragments".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.278(36): 34427–34437.doi:10.1074/jbc.M302659200.PMID12826675.

- ^van Tetering G, van Diest P, Verlaan I, van der Wall E, Kopan R, Vooijs M (November 2009)."Metalloprotease ADAM10 is required for Notch1 site 2 cleavage".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.284(45): 31018–31027.doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.006775.PMC2781502.PMID19726682.

- ^Desbordes S, López-Schier H (2006). "DrosophilaPatterning:Delta-Notch Interactions ".Encyclopedia of Life Sciences.doi:10.1038/npg.els.0004194.ISBN0470016175.

- ^Borggrefe T, Liefke R (January 2012)."Fine-tuning of the intracellular canonical Notch signaling pathway".Cell Cycle.11(2): 264–276.doi:10.4161/cc.11.2.18995.PMID22223095.

- ^Rebay I, Fleming RJ, Fehon RG, Cherbas L, Cherbas P, Artavanis-Tsakonas S (November 1991). "Specific EGF repeats of Notch mediate interactions with Delta and Serrate: implications for Notch as a multifunctional receptor".Cell.67(4): 687–699.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90064-6.PMID1657403.S2CID12643727.

- ^Rebay I, Fleming RJ, Fehon RG, Cherbas L, Cherbas P, Artavanis-Tsakonas S (November 1991). "Specific EGF repeats of Notch mediate interactions with Delta and Serrate: implications for Notch as a multifunctional receptor".Cell.67(4): 687–699.Bibcode:2012Sci...338.1229Y.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90064-6.PMID1657403.S2CID12643727.

- ^"Intrinsic selectivity of Notch 1 for Delta-like 4 over Delta-like 1".Journal of Biological Chemistry.2013.

- ^abLuca VC, Jude KM, Pierce NW, Nachury MV, Fischer S, Garcia KC (February 2015)."Structural biology. Structural basis for Notch1 engagement of Delta-like 4".Science.347(6224): 847–853.Bibcode:2015Sci...347..847L.doi:10.1126/science.1261093.PMC4445638.PMID25700513.

- ^Harmansa S, Affolter M (January 2018)."Protein binders and their applications in developmental biology".Development.145(2): dev148874.doi:10.1242/dev.148874.PMID29374062.

- ^Themeli M, Sadelain M (April 2016)."Combinatorial Antigen Targeting: Ideal T-Cell Sensing and Anti-Tumor Response".Trends in Molecular Medicine.22(4): 271–273.doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2016.02.009.PMC4994806.PMID26971630.

- ^Sadelain M (August 2016)."Chimeric antigen receptors: driving immunology towards synthetic biology".Current Opinion in Immunology.41:68–76.doi:10.1016/j.coi.2016.06.004.PMC5520666.PMID27372731.

- ^Gaiano N, Fishell G (2002). "The role of notch in promoting glial and neural stem cell fates".Annual Review of Neuroscience.25(1): 471–490.doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.030702.130823.PMID12052917.

- ^abcBolós V, Grego-Bessa J, de la Pompa JL (May 2007)."Notch signaling in development and cancer".Endocrine Reviews.28(3): 339–363.doi:10.1210/er.2006-0046.PMID17409286.

- ^Aguirre A, Rubio ME, Gallo V (September 2010)."Notch and EGFR pathway interaction regulates neural stem cell number and self-renewal".Nature.467(7313): 323–327.Bibcode:2010Natur.467..323A.doi:10.1038/nature09347.PMC2941915.PMID20844536.

- ^Hitoshi S, Alexson T, Tropepe V, Donoviel D, Elia AJ, Nye JS, et al. (April 2002)."Notch pathway molecules are essential for the maintenance, but not the generation, of mammalian neural stem cells".Genes & Development.16(7): 846–858.doi:10.1101/gad.975202.PMC186324.PMID11937492.

- ^Liu ZJ, Shirakawa T, Li Y, Soma A, Oka M, Dotto GP, et al. (January 2003)."Regulation of Notch1 and Dll4 by vascular endothelial growth factor in arterial endothelial cells: implications for modulating arteriogenesis and angiogenesis".Molecular and Cellular Biology.23(1): 14–25.doi:10.1128/MCB.23.1.14-25.2003.PMC140667.PMID12482957.

- ^abGrego-Bessa J, Luna-Zurita L, del Monte G, Bolós V, Melgar P, Arandilla A, et al. (March 2007)."Notch signaling is essential for ventricular chamber development".Developmental Cell.12(3): 415–429.doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.011.PMC2746361.PMID17336907.

- ^The notch signaling pathway in cardiac development and tissue homeostasis[permanent dead link]

- ^Murtaugh LC, Stanger BZ, Kwan KM, Melton DA (December 2003)."Notch signaling controls multiple steps of pancreatic differentiation".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.100(25): 14920–14925.Bibcode:2003PNAS..10014920M.doi:10.1073/pnas.2436557100.PMC299853.PMID14657333.

- ^Sander GR, Powell BC (April 2004)."Expression of notch receptors and ligands in the adult gut".The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry.52(4): 509–516.doi:10.1177/002215540405200409.PMID15034002.

- ^abNobta M, Tsukazaki T, Shibata Y, Xin C, Moriishi T, Sakano S, et al. (April 2005)."Critical regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-induced osteoblastic differentiation by Delta1/Jagged1-activated Notch1 signaling".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.280(16): 15842–15848.doi:10.1074/jbc.M412891200.PMID15695512.

- ^Kim PG, Albacker CE, Lu YF, Jang IH, Lim Y, Heffner GC, et al. (January 2013)."Signaling axis involving Hedgehog, Notch, and Scl promotes the embryonic endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.110(2): E141–E150.Bibcode:2013PNAS..110E.141K.doi:10.1073/pnas.1214361110.PMC3545793.PMID23236128.

- ^Laky K, Fowlkes BJ (April 2008)."Notch signaling in CD4 and CD8 T cell development".Current Opinion in Immunology.20(2): 197–202.doi:10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.004.PMC2475578.PMID18434124.

- ^Dontu G, Jackson KW, McNicholas E, Kawamura MJ, Abdallah WM, Wicha MS (2004)."Role of Notch signaling in cell-fate determination of human mammary stem/progenitor cells".Breast Cancer Research.6(6): R605–R615.doi:10.1186/bcr920.PMC1064073.PMID15535842.

- ^Guseh JS, Bores SA, Stanger BZ, Zhou Q, Anderson WJ, Melton DA, Rajagopal J (May 2009)."Notch signaling promotes airway mucous metaplasia and inhibits alveolar development".Development.136(10): 1751–1759.doi:10.1242/dev.029249.PMC2673763.PMID19369400.

- ^Bhandari DR, Seo KW, Roh KH, Jung JW, Kang SK, Kang KS (May 2010). Pera M (ed.)."REX-1 expression and p38 MAPK activation status can determine proliferation/differentiation fates in human mesenchymal stem cells".PLOS ONE.5(5): e10493.Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510493B.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010493.PMC2864743.PMID20463961.

- ^Feller J, Schneider A, Schuster-Gossler K, Gossler A (August 2008)."Noncyclic Notch activity in the presomitic mesoderm demonstrates uncoupling of somite compartmentalization and boundary formation".Genes & Development.22(16): 2166–2171.doi:10.1101/gad.480408.PMC2518812.PMID18708576.

- ^Levin M (January 2005). "Left-right asymmetry in embryonic development: a comprehensive review".Mechanisms of Development.122(1): 3–25.doi:10.1016/j.mod.2004.08.006.PMID15582774.S2CID15211728.

- ^Lambie EJ, Kimble J (May 1991). "Two homologous regulatory genes, lin-12 and glp-1, have overlapping functions".Development.112(1): 231–240.doi:10.1242/dev.112.1.231.PMID1769331.

- ^Gilbert SF (2016).Developmental biology(11th ed.). Sinauer. p. 272.ISBN978-1-60535-470-5.[page needed]

- ^abConlon RA, Reaume AG, Rossant J (May 1995). "Notch1 is required for the coordinate segmentation of somites".Development.121(5): 1533–1545.doi:10.1242/dev.121.5.1533.PMID7789282.

- ^Hrabĕ de Angelis M, McIntyre J, Gossler A (April 1997). "Maintenance of somite borders in mice requires the Delta homologue DII1".Nature.386(6626): 717–721.Bibcode:1997Natur.386..717D.doi:10.1038/386717a0.PMID9109488.S2CID4331445.

- ^van Eeden FJ, Granato M, Schach U, Brand M, Furutani-Seiki M, Haffter P, et al. (December 1996). "Mutations affecting somite formation and patterning in the zebrafish, Danio rerio".Development.123:153–164.doi:10.1242/dev.123.1.153.PMID9007237.

- ^Huppert SS, Ilagan MX, De Strooper B, Kopan R (May 2005)."Analysis of Notch function in presomitic mesoderm suggests a gamma-secretase-independent role for presenilins in somite differentiation".Developmental Cell.8(5): 677–688.doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.019.PMID15866159.

- ^Wahi K, Bochter MS, Cole SE (January 2016). "The many roles of Notch signaling during vertebrate somitogenesis".Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology.49:68–75.doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.11.010.PMID25483003.S2CID10822545.

- ^Lowell S, Jones P, Le Roux I, Dunne J, Watt FM (May 2000)."Stimulation of human epidermal differentiation by delta-notch signalling at the boundaries of stem-cell clusters".Current Biology.10(9): 491–500.Bibcode:2000CBio...10..491L.doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00451-6.PMID10801437.S2CID8927528.

- ^Ezratty EJ, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E (July 2016)."A Presenilin-2-ARF4 trafficking axis modulates Notch signaling during epidermal differentiation".The Journal of Cell Biology.214(1): 89–101.doi:10.1083/jcb.201508082.PMC4932368.PMID27354375.

- ^Poulson DF (March 1937)."Chromosomal Deficiencies and the Embryonic Development of Drosophila Melanogaster".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.23(3): 133–137.Bibcode:1937PNAS...23..133P.doi:10.1073/pnas.23.3.133.PMC1076884.PMID16588136.

- ^abFurukawa T, Mukherjee S, Bao ZZ, Morrow EM, Cepko CL (May 2000)."rax, Hes1, and notch1 promote the formation of Müller glia by postnatal retinal progenitor cells".Neuron.26(2): 383–394.doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81171-X.PMID10839357.S2CID16444353.

- ^abScheer N, Groth A, Hans S, Campos-Ortega JA (April 2001). "An instructive function for Notch in promoting gliogenesis in the zebrafish retina".Development.128(7): 1099–1107.doi:10.1242/dev.128.7.1099.PMID11245575.

- ^abRedmond L, Oh SR, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Ghosh A (January 2000). "Nuclear Notch1 signaling and the regulation of dendritic development".Nature Neuroscience.3(1): 30–40.doi:10.1038/71104.PMID10607392.S2CID14774606.

- ^abCosta RM, Honjo T, Silva AJ (August 2003)."Learning and memory deficits in Notch mutant mice".Current Biology.13(15): 1348–1354.Bibcode:2003CBio...13.1348C.doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00492-5.PMID12906797.S2CID15150614.

- ^Zhong W, Jiang MM, Weinmaster G, Jan LY, Jan YN (May 1997). "Differential expression of mammalian Numb, Numblike and Notch1 suggests distinct roles during mouse cortical neurogenesis".Development.124(10): 1887–1897.doi:10.1242/dev.124.10.1887.PMID9169836.

- ^Li HS, Wang D, Shen Q, Schonemann MD, Gorski JA, Jones KR, et al. (December 2003)."Inactivation of Numb and Numblike in embryonic dorsal forebrain impairs neurogenesis and disrupts cortical morphogenesis".Neuron.40(6): 1105–1118.doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00755-4.PMID14687546.S2CID6525042.

- ^Rash BG, Lim HD, Breunig JJ, Vaccarino FM (October 2011)."FGF signaling expands embryonic cortical surface area by regulating Notch-dependent neurogenesis".The Journal of Neuroscience.31(43): 15604–15617.doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4439-11.2011.PMC3235689.PMID22031906.

- ^Rash BG, Tomasi S, Lim HD, Suh CY, Vaccarino FM (June 2013)."Cortical gyrification induced by fibroblast growth factor 2 in the mouse brain".The Journal of Neuroscience.33(26): 10802–10814.doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3621-12.2013.PMC3693057.PMID23804101.

- ^Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Leker RR, Soldner F, Hoeppner DJ, Ravin R, Poser SW, et al. (August 2006)."Notch signalling regulates stem cell numbers in vitro and in vivo".Nature.442(7104): 823–826.Bibcode:2006Natur.442..823A.doi:10.1038/nature04940.PMID16799564.S2CID4372065.

- ^Rusanescu G, Mao J (October 2014)."Notch3 is necessary for neuronal differentiation and maturation in the adult spinal cord".Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine.18(10): 2103–2116.doi:10.1111/jcmm.12362.PMC4244024.PMID25164209.

- ^Klein AL, Zilian O, Suter U, Taylor V (February 2004)."Murine numb regulates granule cell maturation in the cerebellum".Developmental Biology.266(1): 161–177.doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.017.PMID14729486.

- ^Huang EJ, Li H, Tang AA, Wiggins AK, Neve RL, Zhong W, et al. (January 2005)."Targeted deletion of numb and numblike in sensory neurons reveals their essential functions in axon arborization".Genes & Development.19(1): 138–151.doi:10.1101/gad.1246005.PMC540232.PMID15598981.

- ^Woo HN, Park JS, Gwon AR, Arumugam TV, Jo DG (December 2009). "Alzheimer's disease and Notch signaling".Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications.390(4): 1093–1097.doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.093.PMID19853579.

- ^Presente A, Andres A, Nye JS (October 2001). "Requirement of Notch in adulthood for neurological function and longevity".NeuroReport.12(15): 3321–3325.doi:10.1097/00001756-200110290-00035.PMID11711879.S2CID8329715.

- ^Saura CA, Choi SY, Beglopoulos V, Malkani S, Zhang D, Shankaranarayana Rao BS, et al. (April 2004)."Loss of presenilin function causes impairments of memory and synaptic plasticity followed by age-dependent neurodegeneration".Neuron.42(1): 23–36.doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00182-5.PMID15066262.S2CID17550860.

- ^De Strooper B (November 2014)."Lessons from a failed γ-secretase Alzheimer trial".Cell.159(4): 721–726.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.016.PMID25417150.

- ^Kume T (2012). "Ligand-Dependent Notch Signaling in Vascular Formation".Notch Signaling in Embryology and Cancer.Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 727. pp. 210–222.doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0899-4_16.ISBN978-1-4614-0898-7.PMID22399350.

- ^abcNiessen K, Karsan A (May 2008)."Notch signaling in cardiac development".Circulation Research.102(10): 1169–1181.doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.174318.PMID18497317.

- ^Rutenberg JB, Fischer A, Jia H, Gessler M, Zhong TP, Mercola M (November 2006)."Developmental patterning of the cardiac atrioventricular canal by Notch and Hairy-related transcription factors".Development.133(21): 4381–4390.doi:10.1242/dev.02607.PMC3619037.PMID17021042.

- ^Kokubo H, Tomita-Miyagawa S, Hamada Y, Saga Y (February 2007)."Hesr1 and Hesr2 regulate atrioventricular boundary formation in the developing heart through the repression of Tbx2".Development.134(4): 747–755.doi:10.1242/dev.02777.PMID17259303.

- ^abTimmerman LA, Grego-Bessa J, Raya A, Bertrán E, Pérez-Pomares JM, Díez J, et al. (January 2004)."Notch promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation".Genes & Development.18(1): 99–115.doi:10.1101/gad.276304.PMC314285.PMID14701881.

- ^Crosby CV, Fleming PA, Argraves WS, Corada M, Zanetta L, Dejana E, Drake CJ (April 2005)."VE-cadherin is not required for the formation of nascent blood vessels but acts to prevent their disassembly".Blood.105(7): 2771–2776.doi:10.1182/blood-2004-06-2244.PMID15604224.

- ^Noseda M, McLean G, Niessen K, Chang L, Pollet I, Montpetit R, et al. (April 2004)."Notch activation results in phenotypic and functional changes consistent with endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation".Circulation Research.94(7): 910–917.doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000124300.76171.C9.PMID14988227.

- ^Rones MS, McLaughlin KA, Raffin M, Mercola M (September 2000). "Serrate and Notch specify cell fates in the heart field by suppressing cardiomyogenesis".Development.127(17): 3865–3876.doi:10.1242/dev.127.17.3865.PMID10934030.

- ^Nemir M, Croquelois A, Pedrazzini T, Radtke F (June 2006)."Induction of cardiogenesis in embryonic stem cells via downregulation of Notch1 signaling".Circulation Research.98(12): 1471–1478.doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000226497.52052.2a.PMID16690879.

- ^Croquelois A, Domenighetti AA, Nemir M, Lepore M, Rosenblatt-Velin N, Radtke F, Pedrazzini T (December 2008)."Control of the adaptive response of the heart to stress via the Notch1 receptor pathway".The Journal of Experimental Medicine.205(13): 3173–3185.doi:10.1084/jem.20081427.PMC2605223.PMID19064701.

- ^Collesi C, Zentilin L, Sinagra G, Giacca M (October 2008)."Notch1 signaling stimulates proliferation of immature cardiomyocytes".The Journal of Cell Biology.183(1): 117–128.doi:10.1083/jcb.200806091.PMC2557047.PMID18824567.

- ^Campa VM, Gutiérrez-Lanza R, Cerignoli F, Díaz-Trelles R, Nelson B, Tsuji T, et al. (October 2008)."Notch activates cell cycle reentry and progression in quiescent cardiomyocytes".The Journal of Cell Biology.183(1): 129–141.doi:10.1083/jcb.200806104.PMC2557048.PMID18838555.

- ^Zhao L, Borikova AL, Ben-Yair R, Guner-Ataman B, MacRae CA, Lee RT, et al. (January 2014)."Notch signaling regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation during zebrafish heart regeneration".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.111(4): 1403–1408.Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.1403Z.doi:10.1073/pnas.1311705111.PMC3910613.PMID24474765.

- ^Teske CM."An Evolving Role for Notch Signaling in Heart Regeneration of the Zebrafish Danio rerio".Researchgate.com.Retrieved4 October2022.

- ^Wang J, Sridurongrit S, Dudas M, Thomas P, Nagy A, Schneider MD, et al. (October 2005)."Atrioventricular cushion transformation is mediated by ALK2 in the developing mouse heart".Developmental Biology.286(1): 299–310.doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.035.PMC1361261.PMID16140292.

- ^Xin M, Small EM, van Rooij E, Qi X, Richardson JA, Srivastava D, et al. (May 2007)."Essential roles of the bHLH transcription factor Hrt2 in repression of atrial gene expression and maintenance of postnatal cardiac function".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.104(19): 7975–7980.Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.7975X.doi:10.1073/pnas.0702447104.PMC1876557.PMID17468400.

- ^High FA, Zhang M, Proweller A, Tu L, Parmacek MS, Pear WS, Epstein JA (February 2007)."An essential role for Notch in neural crest during cardiovascular development and smooth muscle differentiation".The Journal of Clinical Investigation.117(2): 353–363.doi:10.1172/JCI30070.PMC1783803.PMID17273555.

- ^Hellström M, Phng LK, Hofmann JJ, Wallgard E, Coultas L, Lindblom P, et al. (February 2007). "Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis".Nature.445(7129): 776–780.Bibcode:2007Natur.445..776H.doi:10.1038/nature05571.PMID17259973.S2CID4407198.

- ^Leslie JD, Ariza-McNaughton L, Bermange AL, McAdow R, Johnson SL, Lewis J (March 2007)."Endothelial signalling by the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 restricts angiogenesis".Development.134(5): 839–844.doi:10.1242/dev.003244.PMID17251261.

- ^Lobov IB, Renard RA, Papadopoulos N, Gale NW, Thurston G, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ (February 2007)."Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) is induced by VEGF as a negative regulator of angiogenic sprouting".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.104(9): 3219–3224.Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.3219L.doi:10.1073/pnas.0611206104.PMC1805530.PMID17296940.

- ^Siekmann AF, Lawson ND (February 2007). "Notch signalling limits angiogenic cell behaviour in developing zebrafish arteries".Nature.445(7129): 781–784.Bibcode:2007Natur.445..781S.doi:10.1038/nature05577.PMID17259972.S2CID4349541.

- ^abSiekmann AF, Lawson ND (2007)."Notch signalling and the regulation of angiogenesis".Cell Adhesion & Migration.1(2): 104–106.doi:10.4161/cam.1.2.4488.PMC2633979.PMID19329884.

- ^Zachary I, Gliki G (February 2001)."Signaling transduction mechanisms mediating biological actions of the vascular endothelial growth factor family".Cardiovascular Research.49(3): 568–581.doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00268-6.PMID11166270.

- ^Williams CK, Li JL, Murga M, Harris AL, Tosato G (February 2006)."Up-regulation of the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 inhibits VEGF-induced endothelial cell function".Blood.107(3): 931–939.doi:10.1182/blood-2005-03-1000.PMC1895896.PMID16219802.

- ^Lawson ND, Scheer N, Pham VN, Kim CH, Chitnis AB, Campos-Ortega JA, Weinstein BM (October 2001). "Notch signaling is required for arterial-venous differentiation during embryonic vascular development".Development.128(19): 3675–3683.doi:10.1242/dev.128.19.3675.PMID11585794.

- ^Apelqvist A, Li H, Sommer L, Beatus P, Anderson DJ, Honjo T, et al. (August 1999). "Notch signalling controls pancreatic cell differentiation".Nature.400(6747): 877–881.Bibcode:1999Natur.400..877A.doi:10.1038/23716.PMID10476967.S2CID4338027.

- ^Lammert E, Brown J, Melton DA (June 2000). "Notch gene expression during pancreatic organogenesis".Mechanisms of Development.94(1–2): 199–203.doi:10.1016/S0925-4773(00)00317-8.PMID10842072.S2CID9931966.

- ^Field HA, Dong PD, Beis D, Stainier DY (September 2003). "Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish. II. Pancreas morphogenesis".Developmental Biology.261(1): 197–208.doi:10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00308-7.PMID12941629.

- ^Jensen J, Pedersen EE, Galante P, Hald J, Heller RS, Ishibashi M, et al. (January 2000). "Control of endodermal endocrine development by Hes-1".Nature Genetics.24(1): 36–44.doi:10.1038/71657.PMID10615124.S2CID52872659.

- ^Jensen J (January 2004)."Gene regulatory factors in pancreatic development".Developmental Dynamics.229(1): 176–200.doi:10.1002/dvdy.10460.PMID14699589.

- ^Norgaard GA, Jensen JN, Jensen J (December 2003)."FGF10 signaling maintains the pancreatic progenitor cell state revealing a novel role of Notch in organ development".Developmental Biology.264(2): 323–338.doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.013.PMID14651921.

- ^abCrosnier C, Vargesson N, Gschmeissner S, Ariza-McNaughton L, Morrison A, Lewis J (March 2005)."Delta-Notch signalling controls commitment to a secretory fate in the zebrafish intestine".Development.132(5): 1093–1104.doi:10.1242/dev.01644.PMID15689380.

- ^Yamada T, Yamazaki H, Yamane T, Yoshino M, Okuyama H, Tsuneto M, et al. (March 2003)."Regulation of osteoclast development by Notch signaling directed to osteoclast precursors and through stromal cells".Blood.101(6): 2227–2234.doi:10.1182/blood-2002-06-1740.PMID12411305.

- ^Watanabe N, Tezuka Y, Matsuno K, Miyatani S, Morimura N, Yasuda M, et al. (2003). "Suppression of differentiation and proliferation of early chondrogenic cells by Notch".Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism.21(6): 344–352.doi:10.1007/s00774-003-0428-4.PMID14586790.S2CID1881239.

- ^Göthert JR, Brake RL, Smeets M, Dührsen U, Begley CG, Izon DJ (November 2007)."NOTCH1 pathway activation is an early hallmark of SCL T leukemogenesis".Blood.110(10): 3753–3762.doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-063644.PMID17698635.

- ^Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JP, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, et al. (October 2004). "Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia".Science.306(5694): 269–271.Bibcode:2004Sci...306..269W.CiteSeerX10.1.1.459.5126.doi:10.1126/science.1102160.PMID15472075.S2CID24049536.

- ^Palomero T, Lim WK, Odom DT, Sulis ML, Real PJ, Margolin A, et al. (November 2006)."NOTCH1 directly regulates c-MYC and activates a feed-forward-loop transcriptional network promoting leukemic cell growth".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.103(48): 18261–18266.Bibcode:2006PNAS..10318261P.doi:10.1073/pnas.0606108103.PMC1838740.PMID17114293.

- ^Rampias T, Vgenopoulou P, Avgeris M, Polyzos A, Stravodimos K, Valavanis C, et al. (October 2014). "A new tumor suppressor role for the Notch pathway in bladder cancer".Nature Medicine.20(10): 1199–1205.doi:10.1038/nm.3678.PMID25194568.S2CID5390234.

- ^Ristic Petrovic A, Stokanović D, Stojnev S, Potić Floranović M, Krstić M, Djordjević I, et al. (July 2022)."The association between NOTCH3 expression and the clinical outcome in the urothelial bladder cancer patients".Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences.22(4): 523–530.doi:10.17305/bjbms.2021.6767.PMC9392971.PMID35073251.

- ^Zhang R, Li S, Schippers K, Eimers B, Niu J, Hornung BV, van den Hout MC, van Ijcken WF, Peppelenbosch MP, Smits R (June 2024)."Unraveling the impact of AXIN1 mutations on HCC development: Insights from CRISPR/Cas9 repaired AXIN1-mutant liver cancer cell lines".PLOS ONE.19(6): e0304607.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0304607.PMC11161089.PMID38848383.

- ^Purow B (2012). "Notch Inhibition as a Promising New Approach to Cancer Therapy".Notch Signaling in Embryology and Cancer.Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 727. pp. 305–319.doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0899-4_23.ISBN978-1-4614-0898-7.PMC3361718.PMID22399357.

- ^Espinoza I, Miele L (August 2013)."Notch inhibitors for cancer treatment".Pharmacology & Therapeutics.139(2): 95–110.doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.02.003.PMC3732476.PMID23458608.

- ^"Notch inhibitors could help overcome therapy resistance in ER-positive breast cancer".2015. Archived fromthe originalon 2015-02-05.Retrieved2015-02-05.

- ^Ramirez Williams L, Brüggemann K, Hubert M, Achmad N, Kiesel L, Schäfer SD, et al. (December 2019)."γ-Secretase inhibition affects viability, apoptosis, and the stem cell phenotype of endometriotic cells".Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.98(12): 1565–1574.doi:10.1111/aogs.13707.PMID31424097.

- ^Schüring AN, Dahlhues B, Korte A, Kiesel L, Titze U, Heitkötter B, et al. (March 2018)."The endometrial stem cell markers notch-1 and numb are associated with endometriosis".Reproductive Biomedicine Online.36(3): 294–301.doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.11.010.PMID29398419.S2CID4912558.

- ^Götte M, Wolf M, Staebler A, Buchweitz O, Kelsch R, Schüring AN, Kiesel L (July 2008). "Increased expression of the adult stem cell marker Musashi-1 in endometriosis and endometrial carcinoma".The Journal of Pathology.215(3): 317–329.doi:10.1002/path.2364.PMID18473332.S2CID206323361.

- ^Erni ST, Gill JC, Palaferri C, Fernandes G, Buri M, Lazarides K, et al. (13 August 2021)."Hair Cell Generation in Cochlear Culture Models Mediated by Novel γ-Secretase Inhibitors".Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.9.Frontiers Media SA: 710159.doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.710159.PMC8414802.PMID34485296.

- ^Samarajeewa A, Jacques BE, Dabdoub A (May 2019)."Therapeutic Potential of Wnt and Notch Signaling and Epigenetic Regulation in Mammalian Sensory Hair Cell Regeneration".Molecular Therapy.27(5). Elsevier BV: 904–911.doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.03.017.PMC6520458.PMID30982678.

- ^Collier JR, Monk NA, Maini PK, Lewis JH (December 1996)."Pattern formation by lateral inhibition with feedback: a mathematical model of delta-notch intercellular signalling".Journal of Theoretical Biology.183(4): 429–446.Bibcode:1996JThBi.183..429C.doi:10.1006/jtbi.1996.0233.PMID9015458.

- ^abBerkemeier F, Page KM (June 2023)."Coupling dynamics of 2D Notch-Delta signalling".Mathematical Biosciences.360:109012.doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2023.109012.PMID37142213.

- ^Vasilopoulos G, Painter KJ (March 2016). "Pattern formation in discrete cell tissues under long range filopodia-based direct cell to cell contact".Mathematical Biosciences.273:1–15.doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2015.12.008.PMID26748293.

- ^Eisen JS (2010-07-27). "Faculty Opinions recommendation of Dynamic filopodia transmit intermittent Delta-Notch signaling to drive pattern refinement during lateral inhibition".doi:10.3410/f.4361976.4187082.

{{cite web}}:Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^Cohen M, Baum B, Miodownik M (June 2011)."The importance of structured noise in the generation of self-organizing tissue patterns through contact-mediated cell-cell signalling".Journal of the Royal Society, Interface.8(59): 787–798.doi:10.1098/rsif.2010.0488.PMC3104346.PMID21084342.

- ^Binshtok U, Sprinzak D (2018). "Modeling the Notch Response". In Borggrefe T, Giaimo B (eds.).Molecular Mechanisms of Notch Signaling.Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1066. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 79–98.doi:10.1007/978-3-319-89512-3_5.ISBN978-3-319-89512-3.PMC6879322.PMID30030823.

- ^Hunter GL, Hadjivasiliou Z, Bonin H, He L, Perrimon N, Charras G, Baum B (July 2016)."Coordinated control of Notch/Delta signalling and cell cycle progression drives lateral inhibition-mediated tissue patterning".Development.143(13): 2305–2310.doi:10.1242/dev.134213.PMC4958321.PMID27226324.

External links

edit- Diagram:notch signaling pathway inHomo sapiens

- Diagram:Notch signaling inDrosophilaArchived2017-11-09 at theWayback Machine

- Notch+Receptorsat the U.S. National Library of MedicineMedical Subject Headings(MeSH)