This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(November 2014) |

Cardiac surgery,orcardiovascular surgery,issurgeryon theheartorgreat vesselsperformed by cardiacsurgeons.It is often used to treat complications ofischemic heart disease(for example, withcoronary artery bypass grafting); to correctcongenital heart disease;or to treatvalvular heart diseasefrom various causes, includingendocarditis,rheumatic heart disease,[1]andatherosclerosis.[2]It also includesheart transplantation.[3]

| Cardiac surgery | |

|---|---|

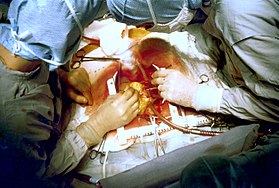

Two cardiac surgeons performingcoronary artery bypass surgery.Note the use of a steelretractorto forcefully maintain the exposure of the heart. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 35-37 |

| MeSH | D006348 |

| OPS-301 code | 5-35...5-37 |

| Cardiac surgery | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Cardiothoracic surgery |

History

edit19th century

editThe earliest operations on thepericardium(the sac that surrounds the heart) took place in the 19th century and were performed byFrancisco Romero(1801) in the city ofAlmería(Spain),[4]Dominique Jean Larrey(1810),Henry Dalton(1891), andDaniel Hale Williams(1893).[5]The first surgery on the heart itself was performed byAxel Cappelenon 4 September 1895 atRikshospitaletin Kristiania, nowOslo.Cappelenligateda bleedingcoronary arteryin a 24-year-old man who had been stabbed in the leftaxillaand was in deepshockupon arrival. Access was through a leftthoracotomy.The patient awoke and seemed fine for 24 hours but became ill with afeverand died three days after the surgery frommediastinitis.[6][7]

20th century

editSurgery on thegreat vessels(e.g.,aortic coarctationrepair,Blalock–Thomas–Taussig shuntcreation, closure ofpatent ductus arteriosus) became common after the turn of the century. However, operations on theheart valveswere unknown until, in 1925,Henry Souttaroperated successfully on a young woman withmitral valve stenosis.He made an opening in the appendage of the leftatriumand inserted a finger in order to palpate and explore the damagedmitral valve.The patient survived for several years,[8]but Souttar's colleagues considered the procedure unjustified, and he could not continue.[9][10]

Alfred Blalock,Helen Taussig,andVivien Thomasperformed the first successful palliativepediatriccardiac operation atJohns Hopkins Hospitalon 29 November 1944, in a one-year-old girl with Tetralogy of Fallot.[11]

Cardiac surgery changed significantly afterWorld War II.In 1947,Thomas SellorsofMiddlesex Hospitalin London operated on aTetralogy of Fallotpatient withpulmonary stenosisand successfully divided the stenosedpulmonary valve.In 1948,Russell Brock,probably unaware of Sellors's work,[12]used a specially designed dilator in three cases of pulmonary stenosis. Later that year, he designed a punch to resect a stenosedinfundibulum,which is often associated with Tetralogy of Fallot. Many thousands of these "blind" operations were performed until the introduction ofcardiopulmonary bypassmade direct surgery on valves possible.[9]

Also in 1948, four surgeons carried out successful operations for mitral valve stenosis resulting fromrheumatic fever.Horace Smithyof Charlotte used avalvulotometo remove a portion of a patient's mitral valve,[13]while three other doctors—Charles BaileyofHahnemann University Hospitalin Philadelphia;Dwight Harkenin Boston; and Russell Brock ofGuy's Hospitalin London—adopted Souttar's method. All four men began their work independently of one another within a period of a few months. This time, Souttar's technique was widely adopted, with some modifications.[9][10]

The first successful intracardiac correction of acongenital heart defectusinghypothermiawas performed by lead surgeon Dr.F. John Lewis[14][15](Dr.C. Walton Lilleheiassisted) at theUniversity of Minnesotaon 2 September 1952. In 1953,Alexander Alexandrovich Vishnevskyconducted the first cardiac surgery underlocal anesthesia.In 1956, Dr. John Carter Callaghan performed the first documented open-heart surgery in Canada.[16]

Types of cardiac surgery

editThis sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(May 2017) |

Open-heart surgery

editOpen-heart surgery is any kind of surgery in which a surgeon makes a large incision (cut) in the chest to open the rib cage and operate on the heart. "Open" refers to the chest, not the heart. Depending on the type of surgery, the surgeon also may open the heart.[17]

Dr.Wilfred G. Bigelowof theUniversity of Torontofound that procedures involving opening the patient's heart could be performed better in a bloodless and motionless environment. Therefore, during such surgery, the heart is temporarily stopped, and the patient is placed oncardiopulmonary bypass,meaning a machine pumps their blood and oxygen. Because the machine cannot function the same way as the heart, surgeons try to minimize the time a patient spends on it.[18]

Cardiopulmonary bypass was developed after surgeons realized the limitations ofhypothermiain cardiac surgery: Complex intracardiac repairs take time, and the patient needs blood flow to the body (particularly to the brain), as well as heart and lung function. In July 1952,Forest Dodrillwas the first to use a mechanical pump in a human to bypass the left side of the heart whilst allowing the patient's lungs to oxygenate the blood, in order to operate on the mitral valve.[19]In 1953, Dr.John Heysham GibbonofJefferson Medical Schoolin Philadelphia reported the first successful use ofextracorporeal circulationby means of anoxygenator,but he abandoned the method after subsequent failures.[20]In 1954, Dr. Lillehei performed a series of successful operations with the controlled cross-circulation technique, in which the patient's mother or father was used as a "heart-lung machine".[21]Dr.John W. Kirklinat theMayo Clinicwas the first to use a Gibbon-type pump-oxygenator.[20][22]

Nazih Zuhdi performed the first total intentional hemodilution open-heart surgery on Terry Gene Nix, age 7, on 25 February 1960 at Mercy Hospital in Oklahoma City. The operation was a success; however, Nix died three years later.[23]In March 1961, Zuhdi, Carey, and Greer performed open-heart surgery on a child, aged3+1⁄2,using the total intentional hemodilution machine.

Modern beating-heart surgery

editIn the early 1990s, surgeons began to performoff-pump coronary artery bypass,done without cardiopulmonary bypass. In these operations, the heart continues beating during surgery, but is stabilized to provide an almost still work area in which to connect a conduit vessel that bypasses a blockage. The conduit vessel that is often used is the saphenous vein. This vein is harvested using a technique known asendoscopic vein harvesting(EVH).

Heart transplant

editIn 1945, the Soviet pathologist Nikolai Sinitsyn successfully transplanted a heart from one frog to another frog and from one dog to another dog.

Norman Shumwayis widely regarded as the father of humanheart transplantation,although the world's first adult heart transplant was performed by aSouth Africancardiac surgeon,Christiaan Barnard,using techniques developed by Shumway andRichard Lower.[24]Barnard performed the first transplant onLouis Washkanskyon 3 December 1967 atGroote Schuur HospitalinCape Town.[24][25]Adrian Kantrowitzperformed the first pediatric heart transplant on 6 December 1967 at Maimonides Hospital (nowMaimonides Medical Center) in Brooklyn, New York, barely three days later.[24]Shumway performed the first adult heart transplant in the United States on 6 January 1968 atStanford University Hospital.[24]

Coronary artery bypass grafting

editCoronary artery bypass grafting(CABG), also called revascularization, is a common surgical procedure to create an alternative path to deliver blood supply to the heart and body, with the goal of preventingclot formation.This can be done in many ways, and thearteriesused can be taken from several areas of the body.[26]Arteries are typically harvested from the chest, arm, or wrist and then attached to a portion of the coronary artery, relieving pressure and limitingclotting factorsin that area of the heart.[27]

The procedure is typically performed because ofcoronary artery disease(CAD), in which a plaque-like substance builds up in the coronary artery, the main pathway carrying oxygen-rich blood to the heart. This can cause a blockage and/or a rupture, which can lead to aheart attack.[27]

Minimally invasive surgery

editAs an alternative to open-heart surgery, which involves a five- to eight-inch incision in thechest wall,a surgeon may perform anendoscopicprocedure by making very small incisions through which a camera and specialized tools are inserted.[28]

Inrobot-assisted heart surgery,a machine controlled by a cardiac surgeon is used to perform a procedure. The main advantage to this is the size of the incision required: three small port holes instead of an incision big enough for the surgeon's hands.[29]The use of robotics in heart surgery continues to be evaluated, but early research has shown it to be a safe alternative to traditional techniques.[30]

Post-surgical procedures

editAs with any surgical procedure, cardiac surgery requires postoperative precautions to avoid complications. Incision care is needed to avoid infection and minimizescarring.Swellingandloss of appetiteare common.[31][32]

Recovery from open-heart surgery begins with about 48 hours in anintensive care unit,whereheart rate,blood pressure,and oxygen levels are closely monitored.Chest tubesare inserted to drain blood around the heart and lungs. After discharge from the hospital,compression socksmay be recommended in order to regulate blood flow.[33]

Risks

editThe advancement of cardiac surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass techniques has greatly reduced the mortality rates of these procedures. For instance, repairs of congenital heart defects are currently estimated to have 4–6% mortality rates.[34][35]

A major concern with cardiac surgery is neurological damage.Strokeoccurs in 2–3% of all people undergoing cardiac surgery, and the rate is higher in patients with other risk factors for stroke.[36]A more subtle complication attributed to cardiopulmonary bypass ispostperfusion syndrome,sometimes called "pumphead". Theneurocognitivesymptoms of postperfusion syndrome were initially thought to be permanent,[37]but turned out to be transient, with no permanent neurological impairment.[38]

In order to assess the performance of surgical units and individual surgeons, a popular risk model has been created called theEuroSCORE.It takes a number of health factors from a patient and, using precalculatedlogistic regressioncoefficients, attempts to quantify the probability that they will survive to discharge. Within theUnited Kingdom,the EuroSCORE was used to give a breakdown of allcardiothoracic surgerycentres and to indicate whether the units and their individuals surgeons performed within an acceptable range. The results are available on theCare Quality Commissionwebsite.[39][40]

Another important source of complications are the neuropsychological and psychopathologic changes following open-heart surgery. One example isSkumin syndrome,described byVictor Skuminin 1978, which is a "cardioprosthetic psychopathological syndrome"[41]associated withmechanical heart valve implantsand characterized by irrational fear,anxiety,depression,sleep disorder,andweakness.[42][43]

Risk reduction

editPharmacological andnon-pharmacologicalprevention approaches may reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation after an operation and reduce the length of hospital stays, however there is no evidence that this improves mortality.[44]

Non-pharmacologic approaches

editPreoperativephysical therapymay reduce postoperative pulmonary complications, such aspneumoniaandatelectasis,in patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery and may decrease the length of hospital stay by more than three days on average.[45]There is evidence that quittingsmokingat least four weeks before surgery may reduce the risk of postoperative complications.[46]

Pharmacological approaches

editBeta-blocking medication is sometimes prescribed during cardiac surgery. There is some low certainty evidence that this perioperative blockade of beta-adrenergic receptors may reduce the incidence ofatrial fibrillationandventricular arrhythmiasin patients undergoing cardiac surgery.[47]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^Lee, KY; Rhim, JW; Kang, JH (March 2012)."Kawasaki disease: laboratory findings and an immunopathogenesis on the premise of a" protein homeostasis system "".Yonsei Medical Journal.53(2): 262–75.doi:10.3349/ymj.2012.53.2.262.PMC3282974.PMID22318812.

- ^"Arteriosclerosis / atherosclerosis - Symptoms and causes".Mayo Clinic.Retrieved6 May2021.

- ^Kilic A, Emani S, Sai-Sudhakar CB, Higgins RS, Whitson BA, et al. (2014)."Donor selection in heart transplantation".Journal of Thoracic Disease.6(8): 1097–1104.doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.03.23.PMC4133543.PMID25132976.

- ^Aris A. (September 1997). "Francisco Romero the first heart surgeon".Ann. Thorac. Surg.64(3): 870–871.doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00760-1.PMID9307502.

- ^"Pioneers in Academic Surgery".U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^Westaby, Stephen; Bosher, Cecil (1998).Landmarks in Cardiac Surgery.Taylor & Francis.ISBN978-1-899066-54-4.

- ^Baksaas ST; Solberg S (January 2003)."Verdens første hjerteoperasjon".Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen.123(2): 202–204.PMID12607508.

- ^Dictionary of National Biography– Henry Souttar (2004–08)

- ^abcHarold Ellis (2000)A History of Surgery,p. 223+[ISBN missing]

- ^abLawrence H Cohn (2007), '&Cardiac Surgery in the Adult,pp. 6+[ISBN missing]

- ^To Heal the Heart of a Child:Helen Taussig, M.D. Joyce Baldwin, Walker and Company New York, 1992[clarification needed][ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^Murtra M (February 2002)."Effects of Growth Hormone Replacement on Parathyroid Hormone Sensitivity and Bone Mineral Metabolism".European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.21(2). The Journal of The Adventure of Cardiac Surgery: 167–180.doi:10.1016/S1010-7940(01)01149-6.PMID11825720.

- ^"About Horace G. Smithy, MD".Medical University of South Carolina. Archived fromthe originalon 30 November 2015.Retrieved5 May2017.

- ^Shumway, Norman E. (January 1996)."F. John Lewis, MD: 1916–1993".The Annals of Thoracic Surgery.61(1): 250–251.doi:10.1016/0003-4975(95)00768-7.PMID8561575.

- ^Knatterud, Mary (8 December 2015)."C. Walton Lillehei, Ph.D., M.D.: The Father of Open-Heart Surgery".Lillehei Heart Institute.University of Minnesota. Archived fromthe originalon 14 December 2019.Retrieved14 December2019.

- ^"Spotlight on UAlberta medical giant: John Callaghan".

- ^"Heart Surgery – What to Expect During Surgery | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)".June 2022.

- ^"A Heart Surgery Overview - Texas Heart Institute".www.texasheart.org.

- ^Stephenson, Larry W.; Arbulu, Agustin; Bassett, Joseph S.; Silbergleit, Allen; Hughes, Calvin H. (May 2002)."Forest Dewey Dodrill: heart surgery pioneer. Michigan Heart, Part II".Journal of Cardiac Surgery.17(3): 247–257, discussion 258–259.doi:10.1111/j.1540-8191.2002.tb01210.x.ISSN0886-0440.PMID12489912.S2CID35545263.

- ^abCohn, Lawrence H. (2003)."Fifty Years of Open-Heart Surgery".Circulation.107(17): 2168–2170.doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000071746.50876.E2.PMID12732590.

- ^Stoney, William S. (2009)."Evolution of Cardiopulmonary Bypass".Circulation.119(21): 2844–2853.doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.830174.PMID19487602.

- ^"Pioneers in Cardiac Surgery: The Mayo-Gibbon Heart-Lung Bypass Machine"(PDF).Mayo Clinic Proceedings Legacy.2014.Archived(PDF)from the original on 26 October 2020.Retrieved24 October2020.

- ^Warren, Cliff, Dr. Nazih Zuhdi – His Scientific Work Made All Paths Lead to Oklahoma City, in Distinctly Oklahoma, November 2007, p. 30–33

- ^abcdMcRae, D.(2007). Every Second Counts. Berkley.

- ^"Memories of the Heart".Daily Intelligencer.Doylestown, Pennsylvania. 29 November 1987. p. A–18.

- ^"What Is Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting? - NHLBI, NIH".www.nhlbi.nih.gov.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^ab"Open Heart Surgery - Cardiac Surgery - University of Rochester Medical Center".www.urmc.rochester.edu.

- ^Open heart surgery: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. (2 February 2016). Retrieved 15 February 2016, fromhttps://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002950.htm

- ^Harky, Amer; Hussain, Syed Mohammad Asim (2019)."Robotic Cardiac Surgery: The Future of Gold Standard or An Unnecessary Extravagance?".Brazilian Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery.34(4): XII–XIII.doi:10.21470/1678-9741-2019-0194.PMC6713378.PMID31454191.

- ^Doulamis, Ilias P.; Spartalis, Eleftherios; Machairas, Nikolaos; Schizas, Dimitrios; Patsouras, Dimitrios; Spartalis, Michael; Tsilimigras, Diamantis I.; Moris, Demetrios; Iliopoulos, Dimitrios C.; Tzani, Aspasia; Dimitroulis, Dimitrios (2019). "The role of robotics in cardiac surgery: a systematic review".Journal of Robotic Surgery.13(1): 41–52.doi:10.1007/s11701-018-0875-5.ISSN1863-2491.PMID30255360.S2CID52821925.

- ^"Heart Surgery | Incision Care".my.clevelandclinic.org.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^"What to Expect After Heart Surgery"(PDF).sts.org.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 August 2017.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^"What To Expect After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting - NHLBI, NIH".www.nhlbi.nih.gov.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^Stark J; Gallivan S; Lovegrove J; et al. (March 2000). "Mortality rates after surgery for congenital heart defects in children and surgeons' performance".Lancet.355(9208): 1004–7.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90001-1.PMID10768449.S2CID26116465.

- ^Klitzner TS; Lee M; Rodriguez S; Chang RK (May 2006). "Sex-related disparity in surgical mortality among pediatric patients".Congenital Heart Disease.1(3): 77–88.doi:10.1111/j.1747-0803.2006.00013.x.PMID18377550.

- ^Naylor AR, Bown MJ (2011)."Stroke after cardiac surgery and its association with asymptomatic carotid disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis".Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg.41(5): 607–24.doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.02.016.PMID21396854.

- ^Newman M; Kirchner J; Phillips-Bute B; Gaver V; Grocott H; et al. (2001)."Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery".N Engl J Med.344(6): 395–402.doi:10.1056/NEJM200102083440601.PMID11172175.

- ^Van Dijk D; Jansen E; Hijman R; Nierich A; Diephuis J; et al. (2002)."Cognitive outcome after off-pump and on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized trial".JAMA.287(11): 1405–12.doi:10.1001/jama.287.11.1405.PMID11903027.

- ^Guida, Pietro; Mastro, Florinda; Scrascia, Giuseppe; Whitlock, Richard; Paparella, Domenico (2014)."Performance of the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II: A meta-analysis of 22 studies involving 145,592 cardiac surgery procedures".Acquired Cardiovascular Disease.148(6): 3049–3057.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.039.PMID25161130.Retrieved24 October2020.

- ^"Heart Surgery in United Kingdom".Archived fromthe originalon 5 November 2011.Retrieved21 October2011.CQC website for heart surgery outcomes in the UK for 3 years ending March 2009

- ^Bendet, Ya. A.; Morozov, S. M.; Skumin, V. A. (1980)."Psychological aspects of the rehabilitation of patients after the surgical treatment of heart defects"Psikhologicheskie aspekty reabilitatsii bol'nykh posle khirurgicheskogo lecheniia porokov serdtsa[Psychological aspects of the rehabilitation of patients after the surgical treatment of heart defects].Kardiologiia.20(6): 45–51.OCLC114137678.PMID7392405.Archived fromthe originalon 5 September 2017.

- ^Skumin, V. A. (1982).Nepsikhoticheskie narusheniia psikhiki u bol'nykh s priobretennymi porokami serdtsa do i posle operatsii (obzor)[Nonpsychotic mental disorders in patients with acquired heart defects before and after surgery (review)].Zhurnal nevropatologii i psikhiatrii imeni S.S. Korsakova.82(11): 130–5.OCLC112979417.PMID6758444.Archived fromthe originalon 29 July 2017.

- ^Ruzza, Andrea (2014). "Nonpsychotic mental disorder after open heart surgery".Asian Cardiovascular and Thoracic Annals.22(3): 374.doi:10.1177/0218492313493427.PMID24585929.S2CID28990767.

- ^Arsenault, Kyle A; Yusuf, Arif M; Crystal, Eugene; Healey, Jeff S; Morillo, Carlos A; Nair, Girish M; Whitlock, Richard P (31 January 2013)."Interventions for preventing post-operative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing heart surgery".Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2021(1): CD003611.doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003611.pub3.PMC7387225.PMID23440790.

- ^Hulzebos, EHJ; Smit Y; Helders PPJM; van Meeteren NLU (14 November 2012)."Preoperative physical therapy for elective cardiac surgery patients".Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.11(11): CD010118.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010118.pub2.PMC8101691.PMID23152283.

- ^Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG)."Complications after surgery: Can quitting smoking before surgery reduce the risks?".Informed Health Online.IQWiG (Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care).Retrieved27 June2013.

- ^Blessberger, Hermann; Lewis, Sharon R.; Pritchard, Michael W.; Fawcett, Lizzy J.; Domanovits, Hans; Schlager, Oliver; Wildner, Brigitte; Kammler, Juergen; Steinwender, Clemens (23 September 2019)."Perioperative beta-blockers for preventing surgery-related mortality and morbidity in adults undergoing cardiac surgery".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.9(10): CD013435.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013435.ISSN1469-493X.PMC6755267.PMID31544227.

Further reading

edit- Cohn, Lawrence H.; Edmunds, L. Henry Jr., eds. (2003).Cardiac surgery in the adult.New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division.ISBN978-0-07-139129-0.Archived fromthe originalon 14 June 2016.

External links

edit- Media related toCardiac surgeryat Wikimedia Commons