Oreis naturalrockorsedimentthat contains one or more valuablemineralsconcentrated above background levels, typically containingmetals,that can be mined, treated and sold at a profit.[1][2][3]The grade of ore refers to the concentration of the desired material it contains. The value of the metals or minerals a rock contains must be weighed against the cost of extraction to determine whether it is of sufficiently high grade to be worth mining and is therefore considered an ore.[4]A complex ore is one containing more than one valuable mineral.[5]

Minerals of interest are generallyoxides,sulfides,silicates,ornative metalssuch ascopperorgold.[5]Ore bodies are formed by a variety ofgeologicalprocesses generally referred to asore genesisand can be classified based on their deposit type. Ore is extracted from the earth throughminingand treated orrefined,often viasmelting,to extract the valuable metals or minerals.[4]Some ores, depending on their composition, may pose threats to health or surrounding ecosystems.

The word ore is ofAnglo-Saxonorigin, meaninglump of metal.[6]

Gangue and tailings

editIn most cases, an ore does not consist entirely of a single mineral, but it is mixed with other valuable minerals and with unwanted or valueless rocks and minerals. The part of an ore that is not economically desirable and that cannot be avoided in mining is known asgangue.[2][3]The valuable ore minerals are separated from the gangue minerals byfroth flotation,gravity concentration, electric or magnetic methods, and other operations known collectively asmineral processing[5][7]orore dressing.[8]

Mineral processing consists of first liberation, to free the ore from the gangue, and concentration to separate the desired mineral(s) from it.[5]Once processed, the gangue is known astailings,which are useless but potentially harmful materials produced in great quantity, especially from lower grade deposits.[5]

Ore deposits

editAn ore deposit is an economically significant accumulation of minerals within a host rock.[9]This is distinct from a mineral resource in that it is a mineral deposit occurring in high enough concentration to be economically viable.[4]An ore deposit is one occurrence of a particular ore type.[10]Most ore deposits are named according to their location, or after a discoverer (e.g. theKambaldanickel shoots are named after drillers),[11]or after some whimsy, a historical figure, a prominent person, a city or town from which the owner came, something from mythology (such as the name of a god or goddess)[12]or the code name of the resource company which found it (e.g. MKD-5 was the in-house name for theMount Keith nickel sulphide deposit).[13]

Classification

editOre deposits are classified according to various criteria developed via the study of economic geology, orore genesis.The following is a general categorization of the main ore deposit types:

Magmatic deposits

editMagmatic deposits are ones who originate directly from magma

- Pegmatitesare very coarse grained, igneous rocks. They crystallize slowly at great depth beneath the surface, leading to their very large crystal sizes. Most are of granitic composition. They are a large source of industrial minerals such asquartz,feldspar,spodumene,petalite,andrare lithophile elements.[14]

- Carbonatitesare an igneous rock whose volume is made up of over 50% carbonate minerals. They are produced from mantle derived magmas, typically at continental rift zones. They contain morerare earth elementsthan any other igneous rock, and as such are a major source of light rare earth elements.[15]

- MagmaticSulfideDeposits form from mantle melts which rise upwards, and gain sulfur through interaction with the crust. This causes the sulfide minerals present to be immiscible, precipitating out when the melt crystallizes.[16][17]Magmatic sulfide deposits can be subdivided into two groups by their dominant ore element:

- Ni-Cu, found inkomatiites,anorthositecomplexes, andflood basalts.[16]This also includes theSudbury Nickel Basin,the only known astrobleme source of such ore.[17]

- Platinum Group Elements(PGE) from largemaficintrusions andtholeiiticrock.[16]

- Stratiform Chromites are strongly linked to PGE magmatic sulfide deposits.[18]These highly mafic intrusions are a source ofchromite,the onlychromiumore.[19]They are so named due to their strata-like shape and formation via layered magmatic injection into the host rock. Chromium is usually located within the bottom of the intrusion. They are typically found within intrusions in continental cratons, the most famous example being theBushveld Complexin South Africa.[18][20]

- Podiform Chromititesare found in ultramafic oceanic rocks resulting from complex magma mixing.[21]They are hosted in serpentine and dunite rich layers and are another source of chromite.[19]

- Kimberlitesare a primary source for diamonds. They originate from depths of 150 km in the mantle and are mostly composed of crustalxenocrysts,high amounts of magnesium, other trace elements, gases, and in some cases diamond.[22]

Metamorphic deposits

editThese are ore deposits which form as a direct result of metamorphism.

- Skarnsoccur in numerous geologic settings worldwide.[23]They are silicates derived from the recrystallization of carbonates likelimestonethroughcontactorregional metamorphism,or fluid relatedmetasomaticevents.[24]Not all are economic, but those with potential value are classified depending on the dominant element such as Ca, Fe, Mg, or Mn among many others.[23][24]They are one of the most diverse and abundant mineral deposits.[24]As such they are classified solely by their common mineralogy, mainlygarnetsandpyroxenes.[23]

- Greisens,like skarns, are a metamorphosed silicate, quartz-mica mineral deposit. Formed from a graniticprotolithdue to alteration by intruding magmas, they are large ore sources oftinandtungstenin the form ofwolframite,cassiterite,stanniteandscheelite.[25][26]

Porphyry copper deposits

editThese are the leading source of copper ore.[27][28]Porphyry copper depositsform alongconvergent boundariesand are thought to originate from the partial melting of subducted oceanic plates and subsequent concentration of Cu, driven by oxidation.[28][29]These are large, round, disseminated deposits containing on average 0.8% copper by weight.[5]

Hydrothermal

Hydrothermal depositsare a large source of ore. They form as a result of the precipitation of dissolved ore constituents out of fluids.[1][30]

- Mississippi Valley-Type(MVT) deposits precipitate from relatively cool, basal brinal fluids within carbonate strata. These are sources ofleadandzincsulphide ore.[31]

- Sediment-Hosted Stratiform Copper Deposits (SSC) form when copper sulphides precipitate out of brinal fluids into sedimentary basins near the equator.[27][32]These are the second most common source of copper ore after porphyry copper deposits, supplying 20% of the worlds copper in addition to silver and cobalt.[27]

- Volcanogenic massive sulphide(VMS) deposits form on the seafloor from precipitation of metal rich solutions, typically associated with hydrothermal activity. They take the general form of a large sulphide rich mound above disseminated sulphides and viens. VMS deposits are a major source ofzinc(Zn),copper(Cu),lead(Pb),silver(Ag), andgold(Au).[33]

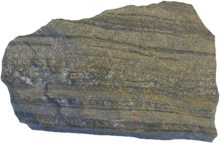

Goldore (size: 7.5 × 6.1 × 4.1 cm) - Sedimentary exhalative sulphide deposits(SEDEX) are a copper sulphide ore which form in the same manor as VMS from metal rich brine but are hosted within sedimentary rocks and are not directly related to volcanism.[25][34]

- Orogenic gold depositsare a bulk source for gold, with 75% of gold production originating from orogenic gold deposits. Formation occurs during late stage mountain building (seeorogeny) where metamorphism forces gold containing fluids into joints and fractures where they precipitate. These tend to be strongly correlated with quartz veins.[1]

- Epithermal vein depositsform in the shallow crust from concentration of metal bearing fluids into veins and stockworks where conditions favour precipitation.[25][19]These volcanic related deposits are a source of gold and silver ore, the primary precipitants.[19]

Sedimentary deposits

editLateritesform from the weathering of highly mafic rock near the equator. They can form in as little as one million years and are a source ofiron(Fe),manganese(Mn), andaluminum(Al).[35]They may also be a source of nickel and cobalt when the parent rock is enriched in these elements.[36]

Banded iron formations(BIFs) are the highest concentration of any single metal available.[1]They are composed of chert beds alternating between high and low iron concentrations.[37]Their deposition occurred early in Earth's history when the atmospheric composition was significantly different from today. Iron rich water is thought to have upwelled where it oxidized to Fe (III) in the presence of early photosynthetic plankton producing oxygen. This iron then precipitated out and deposited on the ocean floor. The banding is thought to be a result of changing plankton population.[38][39]

Sediment Hosted Copper forms from the precipitation of a copper rich oxidized brine into sedimentary rocks. These are a source of copper primarily in the form of copper-sulfide minerals.[40][41]

Placerdeposits are the result of weathering, transport, and subsequent concentration of a valuable mineral via water or wind. They are typically sources of gold (Au),platinum groupelements (PGE),sulfide minerals,tin (Sn),tungsten(W), andrare-earth elements(REEs). A placer deposit is considered alluvial if formed via river, colluvial if by gravity, and eluvial when close to their parent rock.[42][43]

Manganese nodules

editPolymetallic nodules,also called manganese nodules, are mineralconcretionson theseafloor formed of concentric layers ofironandmanganesehydroxidesaround a core.[44]They are formed by a combination ofdiageneticand sedimentary precipitation at the estimated rate of about a centimeter over several million years.[45]The average diameter of a polymetallic nodule is between 3 and 10 cm (1 and 4 in) in diameter and are characterized by enrichment in iron, manganese,heavy metals,andrare earth elementcontent when compared to the Earth's crust and surrounding sediment. The proposed mining of these nodules viaremotely operatedocean floor trawling robots has raised a number of ecological concerns.[46]

Extraction

editThe extraction of ore deposits generally follows these steps.[4]Progression from stages 1–3 will see a continuous disqualification of potential ore bodies as more information is obtained on their viability:[47]

- Prospectingto find where an ore is located. The prospecting stage generally involves mapping,geophysical surveytechniques (aerialand/orground-basedsurveys), geochemical sampling, and preliminary drilling.[47][48]

- After a deposit is discovered,explorationis conducted to define its extent and value via further mapping and sampling techniques such as targeteddiamond drillingto intersect the potential ore body. This exploration stage determines ore grade, tonnage, and if the deposit is a viable economic resource.[47][48]

- Afeasibility studythen considers the theoretical implications of the potential mining operation in order to determine if it should move ahead with development. This includes evaluating the economically recoverable portion of the deposit, marketability and payability of the ore concentrates, engineering, milling and infrastructure costs, finance and equity requirements, potential environmental impacts, political implications, and a cradle to grave analysis from the initial excavation all the way through toreclamation.[47]Multiple experts from differing fields must then approve the study before the project can move on to the next stage.[4]Depending on the size of the project, a pre-feasibility study is sometimes first performed to decide preliminary potential and if a much costlier full feasibility study is even warranted.[47]

- Development begins once an ore body has been confirmed economically viable and involves steps to prepare for its extraction such as building of a mine plant and equipment.[4]

- Production can then begin and is the operation of the mine in an active sense. The time a mine is active is dependent on its remaining reserves and profitability.[4][48]The extraction method used is entirely dependent on the deposit type, geometry, and surrounding geology.[49]Methods can be generally categorized into surface mining such asopen pitorstrip mining,and underground mining such asblock caving,cut and fill, andstoping.[49][50]

- Reclamation,once the mine is no longer operational, makes the land where a mine had been suitable for future use.[48]

With rates of ore discovery in a steady decline since the mid 20th century, it is thought that most surface level, easily accessible sources have been exhausted. This means progressively lower grade deposits must be turned to, and new methods of extraction must be developed.[1]

Hazards

editSome ores containheavy metals,toxins,radioactive isotopesand other potentially negative compounds which may pose a risk to the environment or health. The exact effects an ore and its tailings have is dependent on the minerals present. Tailings of particular concern are those of older mines, as containment and remediation methods in the past were next to non-existent, leading to high levels of leaching into the surrounding environment.[5]Mercuryandarsenicare two ore related elements of particular concern.[51]Additional elements found in ore which may have adverse health affects in organisms include iron, lead, uranium, zinc, silicon, titanium, sulfur, nitrogen, platinum, and chromium.[52]Exposure to these elements may result in respiratory and cardiovascular problems and neurological issues.[52]These are of particular danger to aquatic life if dissolved in water.[5]Ores such as those of sulphide minerals may severely increase the acidity of their immediate surroundings and of water, with numerous, long lasting impacts on ecosystems.[5][53]When water becomes contaminated it may transport these compounds far from the tailings site, greatly increasing the affected range.[52]

Uranium ores and those containing other radioactive elements may pose a significant threat if leaving occurs and isotope concentration increases above background levels. Radiation can have severe, long lasting environmental impacts and cause irreversible damage to living organisms.[54]

History

editMetallurgy began with the direct working of native metals such as gold, lead and copper.[55]Placer deposits, for example, would have been the first source of native gold.[6]The first exploited ores were copper oxides such as malachite and azurite, over 7000 years ago atÇatalhöyük.[56][57][58]These were the easiest to work, with relatively limited mining and basic requirements for smelting.[55][58]It is believed they were once much more abundant on the surface than today.[58]After this, copper sulphides would have been turned to as oxide resources depleted and theBronze Ageprogressed.[55][59]Lead production fromgalenasmelting may have been occurring at this time as well.[6]

The smelting of arsenic-copper sulphides would have produced the first bronze alloys.[56]The majority of bronze creation however required tin, and thus the exploitation of cassiterite, the main tin source, began.[56]Some 3000 years ago, the smelting of iron ores began inMesopotamia.Iron oxide is quite abundant on the surface and forms from a variety of processes.[6]

Until the 18th century gold, copper, lead, iron, silver, tin, arsenic and mercury were the only metals mined and used.[6]In recent decades, Rare Earth Elements have been increasingly exploited for various high-tech applications.[60]This has led to an ever-growing search for REE ore and novel ways of extracting said elements.[60][61]

Trade

editOres (metals) are traded internationally and comprise a sizeable portion of international trade inraw materialsboth in value and volume. This is because the worldwide distribution of ores is unequal and dislocated from locations of peak demand and from smelting infrastructure.

Most base metals (copper, lead, zinc, nickel) are traded internationally on theLondon Metal Exchange,with smaller stockpiles and metals exchanges monitored by theCOMEXandNYMEXexchanges in the United States and the Shanghai Futures Exchange in China. The global Chromium market is currently dominated by the United States and China.[62]

Iron ore is traded between customer and producer, though various benchmark prices are set quarterly between the major mining conglomerates and the major consumers, and this sets the stage for smaller participants.

Other, lesser, commodities do not have international clearing houses and benchmark prices, with most prices negotiated between suppliers and customers one-on-one. This generally makes determining the price of ores of this nature opaque and difficult. Such metals includelithium,niobium-tantalum,bismuth,antimonyandrare earths.Most of these commodities are also dominated by one or two major suppliers with >60% of the world's reserves. China is currently leading in world production of Rare Earth Elements.[63]

TheWorld Bankreports that China was the top importer of ores and metals in 2005 followed by the US and Japan.[64]

Important ore minerals

editFor detailedpetrographicdescriptions of ore minerals seeTables for the Determination of Common Opaque Mineralsby Spry and Gedlinske (1987).[65]Below are the major economic ore minerals and their deposits, grouped by primary elements.

| Type | Mineral | Symbol/formula | Uses | Source(s) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal ore minerals | Aluminum | Al | Alloys,conductive materials, lightweight applications | Gibbsite(Al(OH)3) andaluminium hydroxide oxide,which are found inlaterites.AlsoBauxiteandBarite | [5]' |

| Antimony | Sb | Alloys,flame retardation | Stibnite(Sb2S3) | [5] | |

| Beryllium | Be | Metal alloys, in thenuclear industry,inelectronics | Beryl(Be3Al2Si6O18), found in graniticpegmatites | [5] | |

| Bismuth | Bi | Alloys,pharmeceuticals | Native bismuthandbismuthinite(Bi2S3) with sulphide ores | [5] | |

| Cesium | Cs | Photoelectrics, pharmaceuticals | Lepidolite(K(Li, Al)3(Si, Al)4O10(OH,F)2) frompegmatites | [5] | |

| Chromium | Cr | Alloys,electroplating,colouring agents | Chromite(FeCr2O4) fromstratiformandpodiformchromitites | [5][19][21] | |

| Cobalt | Co | Alloys,chemical catalysts,cemented carbide | Smaltite(CoAs2) in veins withcobaltite;silver,nickelandcalcite;cobaltite(CoAsS) in veins with smaltite, silver, nickel and calcite;carrollite(CuCo2S4) andlinnaeite(Co3S4) as constituents ofcopper ore;andlinnaeite | ||

| Copper | Cu | Alloys, high conductivity,corrosion resistance | Sulphide minerals,includingchalcopyrite(CuFeS2;primary ore mineral) in sulphide deposits, orporphyry copper deposits;covellite(CuS);chalcocite(Cu2S; secondary with other sulphide minerals) withnative copperandcupritedeposits andbornite(Cu5FeS4;secondary with other sulphide minerals) Oxidized minerals, includingmalachite(Cu2CO3(OH)2) in the oxidized zone of copper deposits;cuprite(Cu2O; secondary mineral ); andazurite(Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2;secondary) |

[5][6][28][55] | |

| Gold | Au | Electronics,jewellery,dentistry | Placer deposits,quartzgrains | [5][42][1][66][33][43] | |

| Iron | Fe | Industry use,construction,steel | Hematite(Fe2O3;primary source) inbanded iron formations,veins,andigneous rock;magnetite(Fe3O4) in igneous andmetamorphic rocks;goethite(FeO(OH); secondary to hematite);limonite(FeO(OH)nH2O; secondary to hematite) | [5][1][67] | |

| Lead | Pb | Alloys,pigmentation,batteries,corrosionresistance,radiation shielding | Galena(PbS) in veins with other sulphide materials and inpegmatites;cerussite(PbCO3) in oxidized lead zones along with galena | [5][6][31] | |

| Lithium | Li | Metal production, batteries,ceramics | Spodumene(LiAlSi2O6) in pegmatites | [5] | |

| Manganese | Mn | Steel alloys, chemical manufacturing | Pyrolusite(MnO2) in oxidized manganese zones likelateritesandskarns;manganite(MnO(OH)) andbraunite(3Mn2O3MnSiO3) with pyrolusite | [5][23][35] | |

| Mercury | Hg | Scientific instruments,electrical applications,paint,solvent,pharmeceuticals | Cinnabar(HgS) insedimentaryfractures with other sulphide minerals | [5][6] | |

| Molybdenum | Mo | Alloys, electronics, industry | Molybdenite(MoS2) inporphyry deposits,powellite(CaMoO4) inhydrothermal deposits | [5] | |

| Nickel | Ni | Alloys, food and pharmaceutical applications, corrosion resistance | Pentlandite(Fe,Ni)9S8with other sulphide minerals;garnierite(NiMg) withchromiteand inlaterites;niccolite(NiAs) in magmatic sulphide deposits | [5][16] | |

| Niobium | Nb | Alloys, corrosion resistance | Pyrochlore(Na,Ca)2Nb2O6(OH,F)andcolumbite((FeII,MnII)Nb2O6) in granitic pegmatites | [5] | |

| PlatinumGroup | Pt | Dentistry, jewelry, chemical applications, corrosion resistance, electronics | Withchromiteandcopperore, inplacer deposits;sperrylite(PtAs2) in sulphide deposits and gold veins | [5][68] | |

| Rare-earth elements | La,Ce,Pr,Nd,Pm,Sm,Eu,Gd,Tb,Dy,Ho,Er,Tm,Yb,Lu,Sc,Y | Permanentmagnets,batteries, glass treatment,petroleum industry,micro-electronics,alloys, nuclear applications, corrosion protection (La and Ce are the most widely applicable) | Bastnäsite(REECO3F; for Ce, La, Pr, Nd) incarbonatites;monazite(REEPO4;for La, Ce, Pr, Nd) inplacer deposits;xenotime(YPO4;for Y) inpegmatites;eudialyte(Na15Ca6(Fe,Mn)3Zr3SiO(O,OH,H2O)3 (Si3O9)2(Si9O27)2(OH,Cl)2) in igneous rocks;allanite((REE,Ca,Y)2(Al,Fe2+,Fe3+)3(SiO4)3(OH)) inpegmatitesand carbonatites |

[5][15][60][69][63] | |

| Rhenium | Re | Catalyst,temperature applications | Molybdenite(MoS2) in porphyry deposits | [5][70] | |

| Silver | Ag | Jewellery, glass, photo-electric applications, batteries | Sulfide deposits;Argentite(Ag2S; secondary to copper, lead and zinc ores) | [5][71] | |

| Tin | Sn | Solder,bronze,cans,pewter | Cassiterite(SnO2) in placer and magmatic deposits | [5][56] | |

| Titanium | Ti | Aerospace,industrial tubing | Ilmenite(FeTiO3) andrutile(TiO2) economically sourced from placer deposits withREEs | [5][72] | |

| Tungsten | W | Filaments, electronics, lighting | Wolframite((Fe,Mn)WO4) andscheelite(CaWO4) in skarns and in porphyry along with sulphide minerals | [5][73] | |

| Uranium | U | Nuclear fuel,ammunition,radiation shielding | Pitchblende(UO2) inuraniniteplacer deposits;carnotite(K2(UO2)2(VO4)23H2O) in placer deposits | [5][74] | |

| Vanadium | V | Alloys, catalysts, glass colouring, batteries | Patronite(VS4) with sulphide minerals;roscoelite(K(V,Al,Mg)2AlSi3O10(OH)2) in epithermal gold deposits | [5][75] | |

| Zinc | Zn | Corrosion protection, alloys, various industrial compounds | Sphalerite((Zn,Fe)S) with other sulphide minerals in vein deposits;smithsonite(ZnCO3) in oxidized zone of zinc bearing sulphide deposits | [5][6][31] | |

| Zirconium | Zr | Alloys, nuclear reactors, corrosion resistance | Zircon(ZrSiO4) in igneous rocks and in placers | [5][76] | |

| Non-metal ore minerals | Fluorospar | CaF2 | Steelmaking,optical equipment | Hydrothermal veins and pegmatites | [5][77] |

| Graphite | C | Lubricant,industrial molds, paint | Pegmatites and metamorphic rocks | [5] | |

| Gypsum | CaSO42H2O | Fertilizer,filler,cement,pharmaceuticals,textiles | Evaporites;VMS | [5][78] | |

| Diamond | C | Cutting, jewelry | Kimberlites | [5][22] | |

| Feldspar | Fsp | Ceramics, glassmaking, glazes | Orthoclase(KAlSi3O8) andalbite(NaAlSi3O8) are ubiquitous throughoutEarth's crust | [5] |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^abcdefgJenkin, Gawen R. T.; Lusty, Paul A. J.; McDonald, Iain; Smith, Martin P.; Boyce, Adrian J.; Wilkinson, Jamie J. (2014)."Ore deposits in an evolving Earth: an introduction".Geological Society.393(1): 1–8.doi:10.1144/sp393.14.ISSN0305-8719.S2CID129135737.

- ^ab"Ore".Encyclopædia Britannica.Retrieved2021-04-07.

- ^abNeuendorf, K.K.E.; Mehl, J.P. Jr.; Jackson, J.A., eds. (2011).Glossary of Geology.American Geological Institute. p. 799.

- ^abcdefgHustrulid, William A.; Kuchta, Mark; Martin, Randall K. (2013).Open Pit Mine Planning and Design.Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 1.ISBN978-1-4822-2117-6.Retrieved5 May2020.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakalamanaoWills, B. A. (2015).Wills' mineral processing technology: an introduction to the practical aspects of ore treatment and mineral recovery(8th ed.). Oxford: Elsevier Science & Technology.ISBN978-0-08-097054-7.OCLC920545608.

- ^abcdefghiRapp, George (2009),"Metals and Related Minerals and Ores",Archaeomineralogy,Natural Science in Archaeology, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 143–182,doi:10.1007/978-3-540-78594-1_7,ISBN978-3-540-78593-4,retrieved2023-03-06

- ^Drzymała, Jan (2007).Mineral processing: foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy(PDF)(1st eng. ed.). Wroclaw: University of Technology.ISBN978-83-7493-362-9.Retrieved24 September2021.

- ^Petruk, William (1987). "Applied Mineralogy in Ore Dressing".Mineral Processing Design.pp. 2–36.doi:10.1007/978-94-009-3549-5_2.ISBN978-94-010-8087-3.

- ^Heinrich, C. A.; Candela, P. A. (2014-01-01), Holland, Heinrich D.; Turekian, Karl K. (eds.),"13.1 – Fluids and Ore Formation in the Earth's Crust",Treatise on Geochemistry (Second Edition),Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 1–28,ISBN978-0-08-098300-4,retrieved2023-02-10

- ^Joint Ore Reserves Committee (2012).The JORC Code 2012(PDF)(2012 ed.). p. 44.Retrieved10 June2020.

- ^Chiat, Josh (10 June 2021)."These secret Kambalda mines missed the 2000s nickel boom – meet the company bringing them back to life".Stockhead.Retrieved24 September2021.

- ^Thornton, Tracy (19 July 2020)."Mines of the past had some odd names".Montana Standard.Retrieved24 September2021.

- ^Dowling, S. E.; Hill, R. E. T. (July 1992). "The distribution of PGE in fractionated Archaean komatiites, Western and Central Ultramafic Units, Mt Keith region, Western Australia".Australian Journal of Earth Sciences.39(3): 349–363.Bibcode:1992AuJES..39..349D.doi:10.1080/08120099208728029.

- ^London, David (2018)."Ore-forming processes within granitic pegmatites".Ore Geology Reviews.101:349–383.Bibcode:2018OGRv..101..349L.doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2018.04.020.ISSN0169-1368.

- ^abVerplanck, Philip L.; Mariano, Anthony N.; Mariano Jr, Anthony (2016). "Rare earth element ore geology of carbonatites".Rare earth and critical elements in ore deposits.Littleton, CO: Society of Economic Geologists, Inc. pp. 5–32.ISBN978-1-62949-218-6.OCLC946549103.

- ^abcdNaldrett, A. J. (2011). "Fundamentals of Magmatic Sulfide Deposits".Magmatic Ni-Cu and PGE Deposits: Geology, Geochemistry, and Genesis.Society of Economic Geologists.ISBN9781934969359.

- ^abSong, Xieyan; Wang, Yushan; Chen, Liemeng (2011)."Magmatic Ni-Cu-(PGE) deposits in magma plumbing systems: Features, formation and exploration".Geoscience Frontiers.2(3): 375–384.Bibcode:2011GeoFr...2..375S.doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2011.05.005.

- ^abSchulte, Ruth F.; Taylor, Ryan D.; Piatak, Nadine M.; Seal, Robert R. (2010)."Stratiform chromite deposit model".Open-File Report.doi:10.3133/ofr20101232.ISSN2331-1258.

- ^abcdeMosier, Dan L.; Singer, Donald A.; Moring, Barry C.; Galloway, John P. (2012)."Podiform chromite deposits—database and grade and tonnage models".Scientific Investigations Report.USGS: i–45.doi:10.3133/sir20125157.ISSN2328-0328.

- ^Condie, Kent C. (2022),"Tectonic settings",Earth as an Evolving Planetary System,Elsevier, pp. 39–79,doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-819914-5.00002-0,ISBN978-0-12-819914-5,retrieved2023-03-03

- ^abArai, Shoji (1997)."Origin of podiform chromitites".Journal of Asian Earth Sciences.15(2–3): 303–310.Bibcode:1997JAESc..15..303A.doi:10.1016/S0743-9547(97)00015-9.

- ^abGiuliani, Andrea; Pearson, D. Graham (2019-12-01)."Kimberlites: From Deep Earth to Diamond Mines".Elements.15(6): 377–380.Bibcode:2019Eleme..15..377G.doi:10.2138/gselements.15.6.377.ISSN1811-5217.S2CID214424178.

- ^abcdMeinert, Lawrence D. (1992)."Skarns and Skarn Deposits".Geoscience Canada.19(4).ISSN1911-4850.

- ^abcEinaudi, M. T.; Meinert, L. D.; Newberry, R. J. (1981). "Skarn Deposits".Economic Geology Seventy-fifth anniversary volume.Brian J. Skinner, Society of Economic Geologists (75th ed.). Littleton, Colorado: Society of Economic Geologists.ISBN978-1-934969-53-3.OCLC989865633.

- ^abcPirajno, Franco (1992).Hydrothermal Mineral Deposits: Principles and Fundamental Concepts for the Exploration Geologist.Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.ISBN978-3-642-75671-9.OCLC851777050.

- ^Manutchehr-Danai, Mohsen (2009).Dictionary of gems and gemology.Christian Witschel, Kerstin Kindler (3rd ed.). Berlin: Springer.ISBN9783540727958.OCLC646793373.

- ^abcHayes, Timothy S.; Cox, Dennis P.; Bliss, James D.; Piatak, Nadine M.; Seal, Robert R. (2015)."Sediment-hosted stratabound copper deposit model".Scientific Investigations Report.doi:10.3133/sir20105070m.ISSN2328-0328.

- ^abcLee, Cin-Ty A; Tang, Ming (2020)."How to make porphyry copper deposits".Earth and Planetary Science Letters.529:115868.Bibcode:2020E&PSL.52915868L.doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2019.115868.S2CID208008163.

- ^Sun, Weidong; Wang, Jin-tuan; Zhang, Li-peng; Zhang, Chan-chan; Li, He; Ling, Ming-xing; Ding, Xing; Li, Cong-ying; Liang, Hua-ying (2016)."The formation of porphyry copper deposits".Acta Geochimica.36(1): 9–15.doi:10.1007/s11631-016-0132-4.ISSN2096-0956.S2CID132971792.

- ^Arndt, N. and others (2017) Future mineral resources, Chap. 2, Formation of mineral resources,Geochemical Perspectives, v6-1, p. 18-51.

- ^abcLeach, David L.; Bradley, Dwight; Lewchuk, Michael T.; Symons, David T.; de Marsily, Ghislain; Brannon, Joyce (2001)."Mississippi Valley-type lead–zinc deposits through geological time: implications from recent age-dating research".Mineralium Deposita.36(8): 711–740.Bibcode:2001MinDe..36..711L.doi:10.1007/s001260100208.ISSN0026-4598.S2CID129009301.

- ^Hitzman, M. W.; Selley, D.; Bull, S. (2010)."Formation of Sedimentary Rock-Hosted Stratiform Copper Deposits through Earth History".Economic Geology.105(3): 627–639.Bibcode:2010EcGeo.105..627H.doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.105.3.627.ISSN0361-0128.

- ^abGalley, Alan; Hannington, M.D.; Jonasson, Ian (2007). "Volcanogenic massive sulphide deposits". In Goodfellow, W.D. (ed.).Mineral Deposits of Canada: A Synthesis of Major Deposit-Types, District Metallogeny, the Evolution of Geological Provinces, and Exploration Methods.Geological Association of Canada, Mineral Deposits Division. pp. 141–162.Retrieved2023-02-23.

- ^Hannington, Mark (2021),"VMS and SEDEX Deposits",Encyclopedia of Geology,Elsevier, pp. 867–876,doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102908-4.00075-8,ISBN978-0-08-102909-1,S2CID243007984,retrieved2023-03-03

- ^abPersons, Benjamin S. (1970).Laterite: Genesis, Location, Use.Boston, MA: Springer US.ISBN978-1-4684-7215-8.OCLC840289476.

- ^Marsh, Erin E.; Anderson, Eric D.; Gray, Floyd (2013)."Nickel-cobalt laterites: a deposit model".Scientific Investigations Report.doi:10.3133/sir20105070h.ISSN2328-0328.

- ^Cloud, Preston (1973)."Paleoecological Significance of the Banded Iron-Formation".Economic Geology.68(7): 1135–1143.Bibcode:1973EcGeo..68.1135C.doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.68.7.1135.ISSN1554-0774.

- ^Cloud, Preston E. (1968). "Atmospheric and Hydrospheric Evolution on the Primitive Earth".Science.160(3829): 729–736.Bibcode:1968Sci...160..729C.doi:10.1126/science.160.3829.729.JSTOR1724303.PMID5646415.

- ^Schad, Manuel; Byrne, James M.; ThomasArrigo, Laurel K.; Kretzschmar, Ruben; Konhauser, Kurt O.; Kappler, Andreas (2022)."Microbial Fe cycling in a simulated Precambrian ocean environment: Implications for secondary mineral (trans)formation and deposition during BIF genesis".Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta.331:165–191.Bibcode:2022GeCoA.331..165S.doi:10.1016/j.gca.2022.05.016.S2CID248977303.

- ^Sillitoe, Richard H.; Perelló, José; Creaser, Robert A.; Wilton, John; Wilson, Alan J.; Dawborn, Toby (2017). "Reply to discussions of" Age of the Zambian Copperbelt "by Hitzman and Broughton and Muchez et al".Mineralium Deposita.52(8): 1277–1281.Bibcode:2017MinDe..52.1277S.doi:10.1007/s00126-017-0769-x.S2CID134709798.

- ^Hitzman, Murray; Kirkham, Rodney; Broughton, David; Thorson, Jon; Selley, David (2005),"The Sediment-Hosted Stratiform Copper Ore System",One Hundredth Anniversary Volume,Society of Economic Geologists,doi:10.5382/av100.19,ISBN978-1-887483-01-8,retrieved2023-03-05

- ^abBest, M.E. (2015),"Mineral Resources",Treatise on Geophysics,Elsevier, pp. 525–556,doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53802-4.00200-1,ISBN978-0-444-53803-1,retrieved2023-03-05

- ^abHaldar, S.K. (2013),"Economic Mineral Deposits and Host Rocks",Mineral Exploration,Elsevier, pp. 23–39,doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-416005-7.00002-7,ISBN978-0-12-416005-7,retrieved2023-03-05

- ^Huang, Laiming (2022-09-01)."Pedogenic ferromanganese nodules and their impacts on nutrient cycles and heavy metal sequestration".Earth-Science Reviews.232:104147.doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.104147.ISSN0012-8252.

- ^Kobayashi, Takayuki; Nagai, Hisao; Kobayashi, Koichi (October 2000)."Concentration profiles of 10Be in large manganese crusts".Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms.172(1–4): 579–582.doi:10.1016/S0168-583X(00)00206-8.

- ^Neate, Rupert (2022-04-29)."'Deep-sea gold rush' for rare metals could cause irreversible harm ".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved2023-11-28.

- ^abcdeMarjoribanks, Roger W. (1997).Geological methods in mineral exploration and mining(1st ed.). London: Chapman & Hall.ISBN0-412-80010-1.OCLC37694569.

- ^abcd"The Mining Cycle | novascotia.ca".novascotia.ca.Retrieved2023-02-07.

- ^abOnargan, Turgay (2012).Mining Methods.IntechOpen.ISBN978-953-51-0289-2.

- ^Brady, B. H. G. (2006).Rock mechanics: for underground mining.E. T. Brown (3rd ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.ISBN978-1-4020-2116-9.OCLC262680067.

- ^Franks, DM; Boger, DV; Côte, CM; Mulligan, DR (2011). "Sustainable Development Principles for the Disposal of Mining and Mineral Processing Wastes".Resources Policy.36(2): 114–122.Bibcode:2011RePol..36..114F.doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2010.12.001.

- ^abcda Silva-Rêgo, Leonardo Lucas; de Almeida, Leonardo Augusto; Gasparotto, Juciano (2022)."Toxicological effects of mining hazard elements".Energy Geoscience.3(3): 255–262.Bibcode:2022EneG....3..255D.doi:10.1016/j.engeos.2022.03.003.S2CID247735286.

- ^Mestre, Nélia C.; Rocha, Thiago L.; Canals, Miquel; Cardoso, Cátia; Danovaro, Roberto; Dell’Anno, Antonio; Gambi, Cristina; Regoli, Francesco; Sanchez-Vidal, Anna; Bebianno, Maria João (September 2017)."Environmental hazard assessment of a marine mine tailings deposit site and potential implications for deep-sea mining".Environmental Pollution.228:169–178.doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.027.hdl:10400.1/10388.PMID28531798.

- ^Kamunda, Caspah; Mathuthu, Manny; Madhuku, Morgan (2016-01-18)."An Assessment of Radiological Hazards from Gold Mine Tailings in the Province of Gauteng in South Africa".International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.13(1): 138.doi:10.3390/ijerph13010138.ISSN1660-4601.PMC4730529.PMID26797624.

- ^abcdRostoker, William (1975)."Some Experiments in Prehistoric Copper Smelting".Paléorient.3(1): 311–315.doi:10.3406/paleo.1975.4209.ISSN0153-9345.

- ^abcdPenhallurick, R. D. (2008).Tin in antiquity: its mining and trade throughout the ancient world with particular reference to Cornwall.Minerals, and Mining Institute of Materials (Pbk. ed.). Hanover Walk, Leeds: Maney for the Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining.ISBN978-1-907747-78-6.OCLC705331805.

- ^Radivojević, Miljana; Rehren, Thilo; Pernicka, Ernst; Šljivar, Dušan; Brauns, Michael; Borić, Dušan (2010)."On the origins of extractive metallurgy: new evidence from Europe".Journal of Archaeological Science.37(11): 2775–2787.Bibcode:2010JArSc..37.2775R.doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.06.012.

- ^abcH., Coghlan, H. (1975).Notes on the prehistoric metallurgy of copper and bronze in the Old World: examination of specimens from the Pitt rivers Museum and Bronze castings in ancient moulds, by E. voce.University Press.OCLC610533025.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Amzallag, Nissim (2009)."From Metallurgy to Bronze Age Civilizations: The Synthetic Theory".American Journal of Archaeology.113(4): 497–519.doi:10.3764/aja.113.4.497.ISSN0002-9114.JSTOR20627616.S2CID49574580.

- ^abcMariano, A. N.; Mariano, A. (2012-10-01)."Rare Earth Mining and Exploration in North America".Elements.8(5): 369–376.Bibcode:2012Eleme...8..369M.doi:10.2113/gselements.8.5.369.ISSN1811-5209.

- ^Chakhmouradian, A. R.; Wall, F. (2012-10-01)."Rare Earth Elements: Minerals, Mines, Magnets (and More)".Elements.8(5): 333–340.Bibcode:2012Eleme...8..333C.doi:10.2113/gselements.8.5.333.ISSN1811-5209.

- ^Ren, Shuai; Li, Huajiao; Wang, Yanli; Guo, Chen; Feng, Sida; Wang, Xingxing (2021-10-01)."Comparative study of the China and U.S. import trade structure based on the global chromium ore trade network".Resources Policy.73:102198.Bibcode:2021RePol..7302198R.doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102198.ISSN0301-4207.

- ^abHaque, Nawshad; Hughes, Anthony; Lim, Seng; Vernon, Chris (2014-10-29)."Rare Earth Elements: Overview of Mining, Mineralogy, Uses, Sustainability and Environmental Impact".Resources.3(4): 614–635.doi:10.3390/resources3040614.ISSN2079-9276.

- ^"Background Paper – The Outlook for Metals Markets Prepared for G20 Deputies Meeting Sydney 2006"(PDF).The China Growth Story.WorldBank.org.Washington. September 2006. p. 4.Retrieved2019-07-19.

- ^"Tables For The Determination of Common Opaque Minerals | PDF".Scribd.Retrieved2023-02-10.

- ^John, D.A.; Vikre, P.G.; du Bray, E.A.; Blakely, R.J.; Fey, D.L.; Rockwell, B.W.; Mauk, J.L.; Anderson, E.D.; Graybeal (2018). Descriptive models for epithermal gold-silver deposits: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010 (Report). U.S. Geological Survey. p. 247.doi:10.3133/sir20105070Q.

- ^James, Harold Lloyd (1954-05-01)."Sedimentary facies of iron-formation".Economic Geology.49(3): 235–293.Bibcode:1954EcGeo..49..235J.doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.49.3.235.ISSN1554-0774.

- ^Barkov, Andrei Y.; Zaccarini, Federica (2019).New Results and Advances in PGE Mineralogy in Ni-Cu-Cr-PGE Ore Systems.MDPI, Basel.doi:10.3390/books978-3-03921-717-5.ISBN978-3-03921-717-5.

- ^Chakhmouradian, A. R.; Zaitsev, A. N. (2012-10-01)."Rare Earth Mineralization in Igneous Rocks: Sources and Processes".Elements.8(5): 347–353.Bibcode:2012Eleme...8..347C.doi:10.2113/gselements.8.5.347.ISSN1811-5209.

- ^Engalychev, S. Yu. (2019-04-01)."New Data on the Mineral Composition of Unique Rhenium (U–Mo–Re) Ores of the Briketno-Zheltukhinskoe Deposit in the Moscow Basin".Doklady Earth Sciences.485(2): 355–357.Bibcode:2019DokES.485..355E.doi:10.1134/S1028334X19040019.ISSN1531-8354.S2CID195299595.

- ^Volkov, A. V.; Kolova, E. E.; Savva, N. E.; Sidorov, A. A.; Prokof’ev, V. Yu.; Ali, A. A. (2016-09-01)."Formation conditions of high-grade gold–silver ore of epithermal Tikhoe deposit, Russian Northeast".Geology of Ore Deposits.58(5): 427–441.Bibcode:2016GeoOD..58..427V.doi:10.1134/S107570151605007X.ISSN1555-6476.S2CID133521801.

- ^Charlier, Bernard; Namur, Olivier; Bolle, Olivier; Latypov, Rais; Duchesne, Jean-Clair (2015-02-01)."Fe–Ti–V–P ore deposits associated with Proterozoic massif-type anorthosites and related rocks".Earth-Science Reviews.141:56–81.Bibcode:2015ESRv..141...56C.doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.11.005.ISSN0012-8252.

- ^Yang, Xiaosheng (2018-08-15)."Beneficiation studies of tungsten ores – A review".Minerals Engineering.125:111–119.Bibcode:2018MiEng.125..111Y.doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2018.06.001.ISSN0892-6875.S2CID103605902.

- ^Dahlkamp, Franz J. (1993).Uranium Ore Deposits.Berlin.doi:10.1007/978-3-662-02892-6.ISBN978-3-642-08095-1.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Nejad, Davood Ghoddocy; Khanchi, Ali Reza; Taghizadeh, Majid (2018-06-01)."Recovery of Vanadium from Magnetite Ore Using Direct Acid Leaching: Optimization of Parameters by Plackett–Burman and Response Surface Methodologies".JOM.70(6): 1024–1030.Bibcode:2018JOM....70f1024N.doi:10.1007/s11837-018-2821-4.ISSN1543-1851.S2CID255395648.

- ^Perks, Cameron; Mudd, Gavin (2019-04-01)."Titanium, zirconium resources and production: A state of the art literature review".Ore Geology Reviews.107:629–646.Bibcode:2019OGRv..107..629P.doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2019.02.025.ISSN0169-1368.S2CID135218378.

- ^Hagni, Richard D.; Shivdasan, Purnima A. (2000-04-01)."Characterizing megascopic textures in fluorospar ores at Okorusu mine".JOM.52(4): 17–19.Bibcode:2000JOM....52d..17H.doi:10.1007/s11837-000-0124-y.ISSN1543-1851.S2CID136505544.

- ^Öksüzoğlu, Bilge; Uçurum, Metin (2016-04-01)."An experimental study on the ultra-fine grinding of gypsum ore in a dry ball mill".Powder Technology.291:186–192.doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2015.12.027.ISSN0032-5910.

Further reading

editExternal links

editMedia related toOresat Wikimedia Commons