Thephilosopher's stone[a]is a mythicalchemicalsubstance capable of turningbase metalssuch asmercuryinto gold or silver[b];it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to make anelixir of lifewhich made possiblerejuvenationandimmortality.[1][2]

For many centuries, it was the most sought-after goal inalchemy.The philosopher's stone was the central symbol of the mystical terminology of alchemy, symbolizing perfection at its finest,divine illumination,and heavenly bliss. Efforts to discover the philosopher's stone were known as theMagnum Opus( "Great Work" ).[3]

History

editAntiquity

editThe earliest known written mention of the philosopher's stone is about 4000 years ago in an ancient stone carving,[citation needed]then again in theCheirokmetabyZosimos of Panopolis(c. 300 AD).[4]: 66 Alchemical writers assign a longer history.Elias Ashmoleand the anonymous author ofGloria Mundi(1620) claim that its history goes back toAdam,who acquired the knowledge of the stone directly from God. This knowledge was said to have been passed down through biblical patriarchs, giving them their longevity. The legend of the stone was also compared to the biblical history of theTemple of Solomonand the rejected cornerstone described inPsalm 118.[5]: 19

The theoretical roots outlining the stone's creation can be traced to Greek philosophy. Alchemists later used theclassical elements,the concept ofanima mundi,and Creation stories presented in texts likePlato'sTimaeusas analogies for their process.[6]: 29 According toPlato,the four elements are derived from a common source orprima materia(first matter), associated withchaos.Prima materiais also the name alchemists assign to the starting ingredient for the creation of the philosopher's stone. The importance of this philosophical first matter persisted throughout the history of alchemy. In the seventeenth century,Thomas Vaughanwrites, "the first matter of the stone is the very same with the first matter of all things."[7]: 211

Middle Ages

editIn theByzantine Empireand theArab empires,early medieval alchemists built upon the work of Zosimos. Byzantine andMuslim alchemistswere fascinated by the concept of metal transmutation and attempted to carry out the process.[8]The eighth-centuryMuslimalchemistJabir ibn Hayyan(LatinizedasGeber) analysed each classical element in terms of the four basic qualities. Fire was both hot and dry, earth cold and dry, water cold and moist, and air hot and moist. He theorized that every metal was a combination of these four principles, two of them interior and two exterior. From this premise, it was reasoned that the transmutation of one metal into another could be effected by the rearrangement of its basic qualities. This change would be mediated by a substance, which came to be calledxerionin Greek andal-iksirin Arabic (from which the wordelixiris derived). It was often considered to exist as a dry red powder (also known asal-kibrit al-ahmar,red sulfur) made from a legendary stone—the philosopher's stone.[9][10]The elixir powder came to be regarded as a crucial component of transmutation by later Arab alchemists.[8]

In the 11th century, there was a debate amongMuslim worldchemistson whether the transmutation of substances was possible. A leading opponent was the Persian polymathAvicenna(Ibn Sina), who discredited the theory of the transmutation of substances, stating, "Those of the chemical craft know well that no change can be effected in the different species of substances, though they can produce the appearance of such change."[11]: 196–197

According to legend, the 13th-century scientist and philosopher,Albertus Magnus,is said to have discovered the philosopher's stone. Magnus does not confirm he discovered the stone in his writings, but he did record that he witnessed the creation of gold by "transmutation".[12]: 28–30

Renaissance to early modern period

editThe 16th-centurySwissalchemistParacelsus(Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim) believed in the existence ofalkahest,which he thought to be an undiscovered element from which all other elements (earth, fire, water, air) were simply derivative forms. Paracelsus believed that this element was, in fact, the philosopher's stone.

The English philosopher SirThomas Brownein his spiritual testamentReligio Medici(1643) identified the religious aspect of the quest for the philosopher's Stone when declaring:

The smattering I have of the Philosophers stone, (which is something more than the perfect exaltation of gold) hath taught me a great deale of Divinity.

— (R.M.Part 1:38)[13]

A mystical text published in the 17th century called theMutus Liberappears to be a symbolic instruction manual for concocting a philosopher's stone.[14][15][16]Called the "wordless book", it was a collection of 15 illustrations.

In Buddhism and Hinduism

editThe equivalent of the philosopher's stone inBuddhismandHinduismis theCintamani,also spelled asChintamani.[17]: 277 [better source needed]It is also referred to as Paras/Parasmani (Sanskrit:पारसमणि,Hindi:पारस) or Paris (Marathi:परिस).

In Mahayana Buddhism,Chintamaniis held by thebodhisattvas,AvalokiteshvaraandKsitigarbha.It is also seen carried upon the back of theLung ta(wind horse) which is depicted onTibetanprayer flags.By reciting theDharaniof Chintamani, Buddhist tradition maintains that one attains the Wisdom of Buddhas, is able to understand the truth of the Buddhas, and turns afflictions intoBodhi.It is said to allow one to see the Holy Retinue ofAmitabhaand his assembly upon one's deathbed. In Tibetan Buddhist tradition the Chintamani is sometimes depicted as a luminous pearl and is in the possession of several different forms of the Buddha.[18]: 170

Within Hinduism, it is connected with the godsVishnuandGanesha.In Hindu tradition it is often depicted as a fabulous jewel in the possession of theNāgaking or as on the forehead of theMakara.[citation needed]TheYoga Vasistha,originally written in the tenth century AD, contains a story about the philosopher's stone.[19]: 346–353

A great Hindu sage wrote about the spiritual accomplishment ofGnosisusing the metaphor of the philosopher's stone. SantJnaneshwar(1275–1296) wrote a commentary with 17 references to the philosopher's stone that explicitly transmutes base metal into gold.[citation needed]The seventh-centurySiddharThirumoolarin his classicTirumandhiramexplains man's path to immortal divinity. In verse 2709 he declares that the name of God,Shivais an alchemical vehicle that turns the body into immortal gold.[citation needed]

Another depiction of the philosopher's stone is theShyāmantaka Mani(श्यामन्तक मणि).[citation needed]According to Hindu mythology, the Shyāmantaka Mani is a ruby, capable of preventing all natural calamities such as droughts, floods, etc. around its owner, as well as producing eight bhāras (≈170 pounds or 700 kilograms) of gold, every day.[citation needed]

Properties

editThe most commonly mentioned properties are the ability to transmute base metals into gold or silver, and the ability toheal all forms of illnessand prolong the life of any person who consumes a small part of the philosopher's stone diluted in wine.[20]Other mentioned properties include: creation of perpetually burning lamps,[20]transmutation of common crystals into precious stones and diamonds,[20]reviving of dead plants,[20]creation of flexible or malleable glass,[21]and the creation of a clone orhomunculus.[22]

Names

editNumerous synonyms were used to make oblique reference to the stone, such as "white stone" (calculus albus,identified with thecalculus candidusof Revelation 2:17 which was taken as a symbol of the glory of heaven[23]),vitriol(as expressed in thebackronymVisita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies Occultum Lapidem), alsolapis noster,lapis occultus,in water at the box,and numerous oblique, mystical or mythological references such asAdam,Aer, Animal, Alkahest, Antidotus,Antimonium,Aqua benedicta, Aqua volans per aeram,Arcanum,Atramentum, Autumnus, Basilicus, Brutorum cor, Bufo, Capillus, Capistrum auri, Carbones,Cerberus,Chaos,Cinis cineris,Crocus,Dominus philosophorum, Divine quintessence, Draco elixir, Filius ignis, Fimus, Folium, Frater, Granum, Granum frumenti, Haematites, Hepar, Herba, Herbalis, Lac, Melancholia, Ovum philosophorum, Panacea salutifera,Pandora,Phoenix,Philosophic mercury, Pyrites, Radices arboris solares, Regina, Rex regum, Sal metallorum, Salvator terrenus, Talcum, Thesaurus, Ventus hermetis.[24]Many of the medieval allegories of Christ were adopted for thelapis,and the Christ and the Stone were indeed taken as identical in a mystical sense. The name of "Stone" orlapisitself is informed by early Christian allegory, such asPriscillian(4th century), who stated,

Unicornis est Deus, nobis petra Christus, nobis lapis angularis Jesus, nobis hominum homo Christus(One-horned is God, Christ the rock to us, Jesus the cornerstone to us, Christ the man of men to us.)[25]

In some texts, it is simply called "stone", or our stone, or in the case ofThomas Norton'sOrdinal, "oure delycious stone".[26]The stone was frequently praised and referred to in such terms.

It may be noted that the Latin expressionlapis philosophorum,as well as the Arabicḥajar al-falāsifafrom which the Latin derives, both employ the plural form of the word forphilosopher.Thus a literal translation would bephilosophers' stonerather thanphilosopher's stone.[27]

Appearance

editDescriptions of the philosopher's stone are numerous and various.[28]According to alchemical texts, the stone of the philosophers came in two varieties, prepared by an almost identical method: white (for the purpose of making silver), and red (for the purpose of making gold), the white stone being a less matured version of the red stone.[29]Some ancient and medieval alchemical texts leave clues to the physical appearance of the stone of the philosophers, specifically the red stone. It is often said to be orange (saffron coloured) or red when ground to powder. Or in a solid form, an intermediate between red and purple, transparent and glass-like.[30]The weight is spoken of as being heavier than gold,[31]and it is soluble in any liquid, and incombustible in fire.[32]

Alchemical authors sometimes suggest that the stone's descriptors are metaphorical.[33]The appearance is expressed geometrically inAtalanta FugiensEmblem XXI:

Make of a man and woman a circle; then a quadrangle; out of this a triangle; make again a circle, and you will have the Stone of the Wise. Thus is made the stone, which thou canst not discover, unless you, through diligence, learn to understand this geometrical teaching.

He further describes in greater detail the metaphysical nature of the meaning of the emblem as a divine union of feminine and masculine principles:[34]

In like manner the Philosophers would have the quadrangle reduced into a triangle, that is, into body, Spirit, and Soul, which three do appear in three previous colors before redness, for example, the body or earth in the blackness of Saturn, the Spirit in a lunar whiteness, as water, the Soul or air in a solar citrinity: then will the triangle be perfect, but this likewise must be changed into a circle, that is, into an invariable redness: By which operation the woman is converted into the man, and made one with him, and the senary the first number of the perfect completed by one, two, having returned again to an unit, in which is eternal rest and peace.

Rupescissauses the imagery of the Christian passion, saying that it ascends "from the sepulcher of the Most Excellent King, shining and glorious, resuscitated from the dead and wearing a red diadem...".[35]

Interpretations

editThe various names and attributes assigned to the philosopher's stone have led to long-standing speculation on its composition and source.Exotericcandidates have been found in metals, plants, rocks, chemical compounds, and bodily products such as hair, urine, and eggs.Justus von Liebigstates that 'it was indispensable that every substance accessible... should be observed and examined'.[36]Alchemists once thought a key component in the creation of the stone was a mythicalelementnamed carmot.[37][38]

Esoterichermeticalchemists may reject work on exoteric substances, instead directing their search for the philosopher's stone inward.[39]Though esoteric and exoteric approaches are sometimes mixed, it is clear that some authors "are not concerned with material substances but are employing the language of exoteric alchemy for the sole purpose of expressing theological, philosophical, or mystical beliefs and aspirations".[40]New interpretations continue to be developed aroundspagyric,chemical, and esoteric schools of thought.

The transmutation mediated by the stone has also been interpreted as a psychological process.Idries Shahdevotes a chapter of his book,The Sufis,to provide a detailed analysis of the symbolic significance of alchemical work with the philosopher's stone. His analysis is based in part on a linguistic interpretation through Arabic equivalents of one of the terms for the stone (Azoth) as well as for sulfur, salt, and mercury.[41]

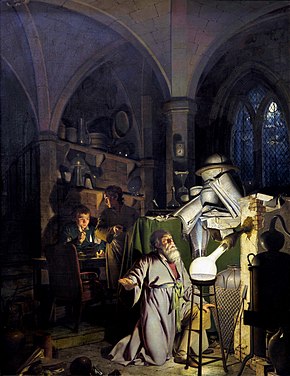

Creation

editThe philosopher's stone is created by the alchemical method known as The Magnum Opus or The Great Work. Often expressed as a series of color changes or chemical processes, the instructions for creating the philosopher's stone are varied. When expressed in colours, the work may pass through phases ofnigredo,albedo,citrinitas,andrubedo.When expressed as a series of chemical processes it often includes seven or twelve stages concluding inmultiplication,andprojection.

Art and entertainment

editThe philosopher's stone has been an inspiration, plot feature, or subject of innumerable artistic works: animations, comics, films, musical compositions, novels, and video games. Examples includeHarry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone,As Above, So Below,Fullmetal Alchemist,The FlashandThe Mystery of Mamo.

The philosopher's stone is an important motif inGothic fiction,and originated inWilliam Godwin's 1799 novelSt. Leon.[42]

See also

editFootnotes

editReferences

edit- ^"philosopher's stone".Britannica.Encyclopedia Britannica. 13 May 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2024.Retrieved17 May2024.

- ^Highfield, Roger."A history of magic: Secrets of the Philosopher's Stone".The British Library.Archivedfrom the original on 20 October 2020.Retrieved27 August2020.

- ^Heindel, Max(June 1978).Freemasonry and Catholicism: an exposition and Investigation.Rosicrucian Fellowship.ISBN0-911274-04-9.Archivedfrom the original on 10 July 2006.Retrieved7 July2006.

- ^Ede, Andrew; Cormack, Lesley.A History of Science in Society: from philosophy to utility.University of Toronto Press.

- ^Patai, Raphael (14 July 2014).The Jewish Alchemists: A History and Source Book.Princeton University Press.ISBN978-1-4008-6366-2.OCLC1165547198.

- ^Linden, Stanton J. (2010).The alchemy reader: from Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-79234-9.OCLC694515596.

- ^Mark, Haeffner (2015).Dictionary of Alchemy From Maria Prophetessa to Isaac Newton.Aeon Books Limited.ISBN978-1-904658-12-2.OCLC957227151.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2023.Retrieved19 November2021.

- ^abStrohmaier, Gotthard (2003). "Umara ibn Hamza, Constantine V, and the invention of the elixir".Hellas im Islam: Interdisziplinare Studien zur Ikonographie, Wissenschaft und Religionsgeschichte.Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 147–150.ISBN9783447046374.

- ^Ragai, Jehane (1992). "The Philosopher's Stone: Alchemy and Chemistry".Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics.12:58–77.doi:10.2307/521636.JSTOR521636.

- ^Holmyard, E. J. (1924). "Maslama al-Majriti and the Rutbatu'l-Hakim".Isis.6(3): 293–305.doi:10.1086/358238.S2CID144175388.

- ^Robert Briffault(1938).The Making of Humanity.

- ^Franklyn, Julian; Budd, F. E. (2001).A Survey of the occult.London: Electric Book Co.ISBN978-1-84327-087-4.OCLC648371829.

- ^The Major Works ed C.A. Patrides Penguin 1977

- ^Dujols, Pierre, alias Magophon,Hypotypose du Mutus Liber,Paris, Editions Nourry, 1914.

- ^Canseliet, Eugène,L'Alchimie et son livre muet,Paris, Pauvert, 1967.

- ^Hutin, Serge,Commentaires sur le Mutus Liber,Paris, Le lien, 1967

- ^René, Guénon (2004).Symbols of sacred science.Sophia Perennis.ISBN0-900588-78-0.OCLC46364629.

- ^Donkin, R. A. (1998).Beyond price: pearls and pearl-fishing: origins to the Age of Discoveries.American Philosophical Society.ISBN9780871692245.

- ^Venkatesananda, Swami(1984).The Concise Yoga Vasistha.Albany. New York:State University of New York Press.ISBN0-87395-955-8.OCLC11044869.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2023.Retrieved21 March2016.

- ^abcdTheophrastus Paracelsus.The Book of the Revelation of Hermes.16th century

- ^Arthur Edward Waite (1893)."IX - A very brief tract concerning the philosophical stone".The Hermetic Museum.Vol. 1. pp. 259–270.Archivedfrom the original on 16 June 2022.Retrieved25 February2022.

Written by an unknown German sage, about 200 years ago, and called the Book of Alze, but now [1893] published for the first time.

- ^Paracelsus, Theophrastus.Of the Nature of Things.16th century

- ^Salomon, Glass (1743).Philologia sacra: qua totius Vet. et Novi Testamenti Scripturae tum stylus et litteratura, tum sensus et genuinae interpretationis ratio et doctrina libris V expenditur ac traditur.J. Fred. Gleditschius.OCLC717819681.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2023.Retrieved19 November2021.

- ^Schneider, W. (1962).Lexikon alchemistisch-pharmazeutischer Symbole.Weinheim.

- ^Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum.t. XVIII. p. 24.as cited inJung, C. G.Roots of Consciousness.

- ^Line 744 in Thomas Norton's The Ordinal of Alchemy by John Rediry. The Early English Text Society no. 272.

- ^As used, for example, byPrincipe 2013(passim,see the pages referenced in the index, p. 278).

- ^John Read "From Alchemy to Chemistry" p.29

- ^A German Sage.A Tract of Great Price Concerning the Philosophical Stone.1423.

- ^John Frederick Helvetius.Golden Calf.17th Century.

- ^Anonymous.On the Philosopher's Stone.(unknown date, possibly 16th century)

- ^Eirenaeus Philalethes.A Brief Guide to the Celestial Ruby.1694 CE

- ^Charles John Samuel Thompson. Alchemy and Alchemists. p.70

- ^Nummedal, Tara; Bilak, Donna (2020).Furnace and Fugue:A Digital Edition of Michael Maier'sAtalanta fugiens(1618) with Scholarly Commentary.Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. Emblem XXI.ISBN978-0-8139-4558-3.Archivedfrom the original on 15 October 2022.Retrieved15 October2022.

- ^Leah DeVun.Prophecy, alchemy, and the end of time: John of Rupescissa in the late Middle Ages.Columbia University Press, 2009. p.118

- ^John Read.From Alchemy to ChemistryLondon: G. Bell. 1957. p. 29.

- ^Burt, A.L. 1885.The National Standard Encyclopedia: A Dictionary of Literature, the Sciences and the Arts, for Popular Usep. 150.Available online.Archived27 November 2019 at theWayback Machine

- ^Sebastian, Anton.1999.A Dictionary of the History of Medicine.p. 179.ISBN1-85070-021-4.Available online.Archived16 March 2023 at theWayback Machine

- ^Stanton J. Linden.The alchemy reader: from Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac NewtonCambridge University Press. 2003. p. 16.

- ^Eric John Holmyard.AlchemyCourier Dover Publications,1990. p. 16.

- ^Shah, Idries (1977) [1964].The Sufis.London, UK: Octagon Press. pp. 192–205.ISBN0-86304-020-9.

- ^Tracy, Ann B. (2015).Gothic Novel 1790–1830: Plot Summaries and Index to Motifs.The University Press of Kentucky.ISBN978-0-8131-6479-3.OCLC1042089949.

Further reading

edit- Encyclopædia Britannica(2011). "Philosopher's stone"and"Alchemy".

- Guiley, Rosemary (2006).The Encyclopedia of Magic and Alchemy.New York: Facts on File.ISBN0-8160-6048-7.pp. 250–252.

- Marlan, Stanton (2014).The Philosophers' Stone: Alchemical Imagination and the Soul's Logical Life.Doctoral dissertation. Pittsburgh, Penn.:Duquesne University.

- Myers, Richard (2003).The Basics of Chemistry.Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group, USA.ISBN0-313-31664-3.pp. 11–12.

- Pagel, Walter(1982).Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance.Basel, Switzerland: Karger Publishers.ISBN3-8055-3518-X.

- Principe, Lawrence M.(2013).The Secrets of Alchemy.Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0226103792.

- Thompson, C. J. S. (2002) [1932].Alchemy and Alchemists.Chapter IX: "The Philosopher's Stone and the Elixir of Life".Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.ISBN0-486-42110-4.pp. 68–76.