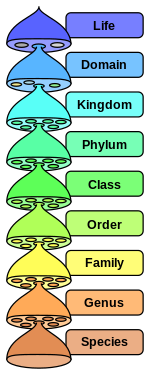

Inbiology,aphylum(/ˈfaɪləm/;pl.:phyla) is a level of classification ortaxonomic rankbelowkingdomand aboveclass.Traditionally, inbotanythe termdivisionhas been used instead of phylum, although theInternational Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plantsaccepts the terms as equivalent.[1][2][3]Depending on definitions, the animal kingdomAnimaliacontains about 31 phyla, the plant kingdomPlantaecontains about 14 phyla, and the fungus kingdomFungicontains about eight phyla. Current research inphylogeneticsis uncovering the relationships among phyla within largercladeslikeEcdysozoaandEmbryophyta.

General description

editThe term phylum was coined in 1866 byErnst Haeckelfrom the Greekphylon(φῦλον,"race, stock" ), related tophyle(φυλή,"tribe, clan" ).[4][5]Haeckel noted that species constantly evolved into new species that seemed to retain few consistent features among themselves and therefore few features that distinguished them as a group ( "a self-contained unity" ): "perhaps such a real and completely self-contained unity is the aggregate of all species which have gradually evolved from one and the same common original form, as, for example, all vertebrates. We name this aggregate [a]Stamm[i.e., stock] (Phylon). "[a]Inplant taxonomy,August W. Eichler(1883) classified plants intofive groupsnamed divisions, a term that remains in use today for groups of plants, algae and fungi.[1][6] The definitions of zoological phyla have changed from their origins in the sixLinnaeanclasses and the fourembranchementsofGeorges Cuvier.[7]

Informally, phyla can be thought of as groupings of organisms based on general specialization ofbody plan.[8]At its most basic, a phylum can be defined in two ways: as a group of organisms with a certain degree of morphological or developmental similarity (thepheneticdefinition), or a group of organisms with a certain degree of evolutionary relatedness (thephylogeneticdefinition).[9]Attempting to define a level of theLinnean hierarchywithout referring to (evolutionary) relatedness is unsatisfactory, but a phenetic definition is useful when addressing questions of a morphological nature—such as how successful different body plans were.[citation needed]

Definition based on genetic relation

editThe most important objective measure in the above definitions is the "certain degree" that defines how different organisms need to be members of different phyla. The minimal requirement is that all organisms in a phylum should be clearly more closely related to one another than to any other group.[9]Even this is problematic because the requirement depends on knowledge of organisms' relationships: as more data become available, particularly from molecular studies, we are better able to determine the relationships between groups. So phyla can be merged or split if it becomes apparent that they are related to one another or not. For example, thebearded wormswere described as a new phylum (the Pogonophora) in the middle of the 20th century, but molecular work almost half a century later found them to be a group ofannelids,so the phyla were merged (the bearded worms are now an annelidfamily).[10]On the other hand, the highly parasitic phylumMesozoawas divided into two phyla (OrthonectidaandRhombozoa) when it was discovered the Orthonectida are probablydeuterostomesand the Rhombozoaprotostomes.[11]

This changeability of phyla has led some biologists to call for the concept of a phylum to be abandoned in favour of placing taxa incladeswithout any formal ranking of group size.[9]

Definition based on body plan

editA definition of a phylum based on body plan has been proposed by paleontologistsGraham BuddandSören Jensen(as Haeckel had done a century earlier). The definition was posited because extinct organisms are hardest to classify: they can be offshoots that diverged from a phylum's line before the characters that define the modern phylum were all acquired. By Budd and Jensen's definition, a phylum is defined by a set of characters shared by all its living representatives.

This approach brings some small problems—for instance, ancestral characters common to most members of a phylum may have been lost by some members. Also, this definition is based on an arbitrary point of time: the present. However, as it is character based, it is easy to apply to the fossil record. A greater problem is that it relies on a subjective decision about which groups of organisms should be considered as phyla.

The approach is useful because it makes it easy to classify extinct organisms as "stem groups"to the phyla with which they bear the most resemblance, based only on the taxonomically important similarities.[9]However, proving that a fossil belongs to thecrown groupof a phylum is difficult, as it must display a character unique to a sub-set of the crown group.[9]Furthermore, organisms in the stem group of a phylum can possess the "body plan" of the phylum without all the characteristics necessary to fall within it. This weakens the idea that each of the phyla represents a distinct body plan.[12]

A classification using this definition may be strongly affected by the chance survival of rare groups, which can make a phylum much more diverse than it would be otherwise.[13]

Known phyla

editAnimals

editThis sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(February 2013) |

Total numbers are estimates; figures from different authors vary wildly, not least because some are based on described species,[14]some on extrapolations to numbers of undescribed species. For instance, around 25,000–27,000 species of nematodes have been described, while published estimates of the total number of nematode species include 10,000–20,000; 500,000; 10 million; and 100 million.[15]

| Protostome | Bilateria | Nephrozoa | |

| Deuterostome | |||

| Basal/disputed | Non-Bilateria | ||

| Vendobionta | |||

| Parazoa | |||

| Others | |||

| Phylum | Meaning | Common name | Distinguishing characteristic | Taxa described |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agmata | Fragmented | Calcareous conical shells | 5 species, extinct | |

| Annelida | Little ring[16]: 306 | Segmented worms, annelids | Multiple circular segments | 22,000+ extant |

| Arthropoda | Jointed foot | Arthropods | Segmented bodies and jointed limbs, withChitinexoskeleton | 1,250,000+ extant;[14]20,000+ extinct |

| Brachiopoda | Arm foot[16]: 336 | Lampshells[16]: 336 | Lophophoreandpedicle | 300–500 extant; 12,000+ extinct |

| Bryozoa(Ectoprocta) | Moss animals | Moss animals, sea mats, ectoprocts[16]: 332 | Lophophore, no pedicle,ciliatedtentacles,anus outside ring of cilia | 6,000extant[14] |

| Chaetognatha | Longhair jaw | Arrow worms[16]: 342 | Chitinousspines either side of head, fins | approx.100extant |

| Chordata | With a cord | Chordates | Hollowdorsal nerve cord,notochord,pharyngeal slits,endostyle,post-analtail | approx. 55,000+[14] |

| Cnidaria | Stinging nettle | Cnidarians | Nematocysts(stinging cells) | approx. 16,000[14] |

| Ctenophora | Comb bearer | Comb jellies[16]: 256 | Eight "comb rows" of fused cilia | approx. 100–150 extant |

| Cycliophora | Wheel carrying | Circular mouth surrounded by small cilia, sac-like bodies | 3+ | |

| Echinodermata | Spiny skin | Echinoderms[16]: 348 | Fivefold radialsymmetryin living forms,mesodermalcalcified spines | approx. 7,500extant;[14]approx. 13,000 extinct |

| Entoprocta | Insideanus[16]: 292 | Goblet worms | Anus inside ring of cilia | approx. 150 |

| Gastrotricha | Hairy stomach[16]: 288 | Hairybellies | Two terminal adhesive tubes | approx. 690 |

| Gnathostomulida | Jaw orifice | Jaw worms[16]: 260 | Tiny worms related to rotifers with no body cavity | approx. 100 |

| Hemichordata | Half cord[16]: 344 | Acorn worms, hemichordates | Stomochordin collar,pharyngeal slits | approx. 130extant |

| Kinorhyncha | Motion snout | Mud dragons | Eleven segments, each with a dorsal plate | approx. 150 |

| Loricifera | Armourbearer | Brush heads | Umbrella-like scales at each end | approx. 122 |

| Micrognathozoa | Tiny jaw animals | Accordion-like extensiblethorax | 1 | |

| Mollusca | Soft[16]: 320 | Mollusks/molluscs | Muscular foot andmantleround shell | 85,000+ extant;[14]80,000+ extinct[17] |

| Monoblastozoa (Nomen inquirendum) |

One sprout animals | distinct anterior/posterior parts and being densely ciliated, especially around the "mouth" and "anus". | 1 | |

| Nematoda | Thread like | Roundworms, threadworms, eelworms, nematodes[16]: 274 | Round cross section,keratincuticle | 25,000[14] |

| Nematomorpha | Thread form[16]: 276 | Horsehair worms, Gordian worms[16]: 276 | Long, thin parasitic worms closely related to nematodes | approx. 320 |

| Nemertea | A sea nymph[16]: 270 | Ribbon worms[16]: 270 | Unsegmented worms, with a proboscis housed in a cavity derived from the coelom called the rhynchocoel | approx. 1,200 |

| Onychophora | Claw bearer | Velvet worms[16]: 328 | Worm-like animal with legs tipped by chitinous claws | approx. 200extant |

| Orthonectida | Straight swimmer | Parasitic, microscopic, simple, wormlike organisms | 20 | |

| Petalonamae | Shaped like leaves | An extinct phylum from the Ediacaran. They are bottom-dwelling and immobile, shaped like leaves (frondomorphs), feathers or spindles. | 3 classes, extinct | |

| Phoronida | Zeus's mistress | Horseshoe worms | U-shaped gut | 11 |

| Placozoa | Plate animals | Trichoplaxes, placozoans[16]: 242 | Differentiated top and bottom surfaces, two ciliated cell layers, amoeboid fiber cells in between | 4+ |

| Platyhelminthes | Flat worm[16]: 262 | Flatworms[16]: 262 | Flattened worms with no body cavity. Many are parasitic. | approx. 29,500[14] |

| Porifera | Pore bearer | Sponges[16]: 246 | Perforated interior wall, simplest of all known animals | 10,800extant[14] |

| Priapulida | LittlePriapus | Penis worms | Penis-shaped worms | approx. 20 |

| Proarticulata | Before articulates | An extinct group of mattress-like organisms that display "glide symmetry." Found during the Ediacaran. | 3 classes, extinct | |

| Dicyemida | Lozenge animal | Singleanteroposterioraxialcelledendoparasites, surrounded by ciliated cells | 100+ | |

| Rotifera | Wheel bearer | Rotifers[16]: 282 | Anterior crown of cilia | approx. 3,500[14] |

| Saccorhytida | Saccus: "pocket" and "wrinkle" | Saccorhytusis only about 1 mm (1.3 mm) in size and is characterized by a spherical or hemispherical body with a prominent mouth. Its body is covered by a thick but flexible cuticle. It has a nodule above its mouth. Around its body are 8 openings in a truncated cone with radial folds. Considered to be a deuterostome[18]or an earlyecdysozoan.[19] | 2 species, extinct | |

| Tardigrada | Slow step | Water bears, moss piglets | Microscopic relatives of the arthropods, with a four segmented body and head | 1,000 |

| Trilobozoa | Three-lobed animal | Trilobozoans | A taxon of mostly discoidal organisms exhibiting tricentric symmetry. All are Ediacaran-aged | 18 genera, extinct |

| Vetulicolia | Ancient dweller | Vetulicolians | Might possibly be a subphylum of the chordates. Their body consists of two parts: a large front part and covered with a large "mouth" and a hundred round objects on each side that have been interpreted as gills or openings near the pharynx. Their posterior pharynx consists of 7 segments. | 15 species, extinct |

| Xenacoelomorpha | Strange hollow form | Xenacoelomorphs | Small, simple animals.Bilaterian,but lacking typical bilaterian structures such as gut cavities, anuses, and circulatory systems[20] | 400+ |

| Total: 39 | 1,525,000[14] |

Plants

editThe kingdom Plantae is defined in various ways by different biologists (seeCurrent definitions of Plantae). All definitions include the livingembryophytes(land plants), to which may be added the two green algae divisions,ChlorophytaandCharophyta,to form the cladeViridiplantae.The table below follows the influential (though contentious)Cavalier-Smith systemin equating "Plantae" withArchaeplastida,[21]a group containing Viridiplantae and the algalRhodophytaandGlaucophytadivisions.

The definition and classification of plants at the division level also varies from source to source, and has changed progressively in recent years. Thus some sources place horsetails in division Arthrophyta and ferns in division Monilophyta,[22]while others place them both in Monilophyta, as shown below. The division Pinophyta may be used for allgymnosperms(i.e. including cycads, ginkgos and gnetophytes),[23]or for conifers alone as below.

Since the first publication of theAPG systemin 1998, which proposed a classification ofangiospermsup to the level oforders,many sources have preferred to treat ranks higher than orders as informal clades. Where formal ranks have been provided, the traditional divisions listed below have been reduced to a very much lower level, e.g.subclasses.[24]

| Land plants | Viridiplantae | |

| Green algae | ||

| Other algae (Biliphyta)[21] | ||

| Division | Meaning | Common name | Distinguishing characteristics | Species described |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthocerotophyta[25] | Anthoceros-like plants | Hornworts | Horn-shapedsporophytes,no vascular system | 100–300+ |

| Bryophyta[25] | Bryum-like plants, moss plants | Mosses | Persistent unbranchedsporophytes,no vascular system | approx. 12,000 |

| Charophyta | Chara-like plants | Charophytes | approx. 1,000 | |

| Chlorophyta | (Yellow-)green plants[16]: 200 | Chlorophytes | approx. 7,000 | |

| Cycadophyta[26] | Cycas-like plants, palm-like plants | Cycads | Seeds, crown of compound leaves | approx. 100–200 |

| Ginkgophyta[27] | Ginkgo-like plants | Ginkgophytes | Seeds not protected by fruit | only 1extant; 50+ extinct |

| Glaucophyta | Blue-green plants | Glaucophytes | 15 | |

| Gnetophyta[28] | Gnetum-like plants | Gnetophytes | Seeds and woody vascular system with vessels | approx. 70 |

| Lycophyta[29] | Lycopodium-like plants Wolf plants |

Clubmosses | Microphyllleaves,vascular system | 1,290extant |

| Angiospermae | Seed container | Flowering plants, angiosperms | Flowers and fruit, vascular system with vessels | 300,000 |

| Marchantiophyta,[30] Hepatophyta[25] |

Marchantia-like plants Liver plants |

Liverworts | Ephemeral unbranchedsporophytes,no vascular system | approx. 9,000 |

| Polypodiophyta | Polypodium-like plants |

Ferns | Megaphyllleaves,vascular system | approx. 10,560 |

| Picozoa | Extremely small animals | Picozoans, picobiliphytes | 1 | |

| Pinophyta,[23] Coniferophyta[31] |

Pinus-like plants Cone-bearing plant |

Conifers | Cones containing seeds and wood composed of tracheids | 629extant |

| Prasinodermophyta | Prasinoderma-like plants | Picozoans, picobiliphytes, biliphytes | 8 | |

| Rhodophyta | Rose plants | Red algae | Usephycobiliproteinsasaccessory pigments. | approx. 7,000 |

| Total: 14 |

Fungi

edit| Division | Meaning | Common name | Distinguishing characteristics | Species described |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | Bladder fungus[16]: 396 | Ascomycetes,[16]: 396 sac fungi | Tend to have fruiting bodies (ascocarp).[32]Filamentous, producing hyphae separated by septa. Can reproduce asexually.[33] | 30,000 |

| Basidiomycota | Small base fungus[16]: 402 | Basidiomycetes,[16]: 402 club fungi | Bracket fungi, toadstools, smuts and rust. Sexual reproduction.[34] | 31,515 |

| Blastocladiomycota | Offshoot branch fungus[35] | Blastoclads | Less than 200 | |

| Chytridiomycota | Little cooking pot fungus[36] | Chytrids | Predominantly Aquaticsaprotrophicor parasitic. Have a posteriorflagellum.Tend to be single celled but can also be multicellular.[37][38][39] | 1000+ |

| Glomeromycota | Ball of yarn fungus[16]: 394 | Glomeromycetes,AMfungi[16]: 394 | Mainly arbuscular mycorrhizae present, terrestrial with a small presence on wetlands. Reproduction is asexual but requires plant roots.[34] | 284 |

| Microsporidia | Small seeds[40] | Microsporans[16]: 390 | 1400 | |

| Neocallimastigomycota | New beautiful whip fungus[41] | Neocallimastigomycetes | Predominantly located in digestive tract of herbivorous animals. Anaerobic, terrestrial and aquatic.[42] | approx. 20[43] |

| Zygomycota | Pair fungus[16]: 392 | Zygomycetes[16]: 392 | Most are saprobes and reproduce sexually and asexually.[42] | approx. 1060 |

| Total: 8 |

Phylum Microsporidia is generally included in kingdom Fungi, though its exact relations remain uncertain,[44]and it is considered aprotozoanby the International Society of Protistologists[45](seeProtista,below). Molecular analysis of Zygomycota has found it to bepolyphyletic(its members do not share an immediate ancestor),[46]which is considered undesirable by many biologists. Accordingly, there is a proposal to abolish the Zygomycota phylum. Its members would be divided between phylum Glomeromycota and four new subphylaincertae sedis(of uncertain placement):Entomophthoromycotina,Kickxellomycotina,Mucoromycotina,andZoopagomycotina.[44]

Protists

editKingdomProtista(or Protoctista) is included in the traditional five- or six-kingdom model, where it can be defined as containing alleukaryotesthat are not plants, animals, or fungi.[16]: 120 Protista is aparaphyletictaxon,[47]which is less acceptable to present-day biologists than in the past. Proposals have been made to divide it among several new kingdoms, such asProtozoaandChromistain theCavalier-Smith system.[48]

Protist taxonomy has long been unstable,[49]with different approaches and definitions resulting in many competing classification schemes. Many of the phyla listed below are used by theCatalogue of Life,[50]and correspond to the Protozoa-Chromista scheme,[45]with updates from the latest (2022) publication byCavalier-Smith.[51]Other phyla are used commonly by other authors, and are adapted from the system used by the International Society of Protistologists (ISP). Some of the descriptions are based on the 2019 revision of eukaryotes by the ISP.[52]

| Stramenopiles | "Chromista" | |

| Alveolata | ||

| Rhizaria | ||

| "Hacrobia" | ||

| "Sarcomastigota" | "Protozoa" | |

| "Excavata" | ||

| Orphan groups | ||

| Phylum | Meaning | Common name | Distinguishing characteristics | Species described | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoebozoa | Amorphous animals | Amoebozoans | Presence ofpseudopodiaforamoeboidmovement, tubularcristae.[52] | approx. 2,400[53] | |

| Apicomplexa | Apical infolds[54] | Apicomplexans, sporozoans | Mostly parasitic, at least one stage of the life cycle with flattened subpellicular vesicles and a complete apical complex, non-photosyntheticapicoplast.[52] | over 6,000[54] | |

| Apusozoa (paraphyletic) |

Apusomonas-like animals | Glidingbiciliateswith two or three connectors betweencentrioles | 32 | ||

| Bigyra | Two rings | Stramenopileswith a double helix in ciliary transition zone | |||

| Cercozoa | Flagellated animal | Cercozoans | Defined bymolecular phylogeny,lacking distinctive morphological or behavioural characters.[52] | ||

| Chromerida | Chromera-like organisms | Chrompodellids, chromerids, colpodellids[55] | Biflagellates, chloroplasts with four membranes, incomplete apical complex, cortical alveoli, tubular cristae.[52] | 8[56] | |

| Choanozoa (paraphyletic) |

Funnel animals[16] | Opisthokont protists | Filose pseudopods;some with acolar of microvillisurrounding aflagellum | approx. 300[53] | |

| Ciliophora | Cilia bearers | Ciliates | Presence of multiple cilia and acytostome. | approx. 4,500[57] | |

| Cryptista | Hidden[16] | Defined bymolecular phylogeny,flat cristae.[52] | 246[56][52] | ||

| Dinoflagellata | Whirling flagellates[16] | Dinoflagellates | Biflagellates with a transverse ribbon-like flagellum with multiple waves beating to the cell’s left and a longitudinal flagellum beating posteriorly with only one or few waves.[52] | 2,957extant 955 fossil[56] |

|

| Endomyxa | Within mucus[16][58] | Defined bymolecular phylogeny,[52]typically plasmodial endoparasites of other eukaryotes.[58] | |||

| Eolouka (paraphyletic) |

Early groove[59] | Heterotrophic biflagellates with ventral feeding groove.[59] | 23 | ||

| Euglenozoa | True eye animals | Biflagellates, one of the twociliainserted into an apical or subapical pocket, unique ciliary configuration.[52] | 2,037extant 20 fossil[56] |

||

| Ochrophyta, Heterokontophyta |

Ochreplants, heterokont plants | Heterokont algae, stramenochromes, ochrophytes, heterokontophytes | Biflagellates with tripartite mastigonemes, chloroplasts with four membranes and chlorophyllsaandc,tubular cristae.[52] | 21,052extant 2,262 fossil[56] |

|

| Haptista | Fasten[16] | Thinmicrotubule-based appendages for feeding (haptonema inhaptophytes,axopodiaincentrohelids), complex mineralized scales.[52] | 517extant 1,205 fossil[56] |

||

| Hemimastigophora | Incomplete or atypical flagellates[60] | Hemimastigotes[61] | Ellipsoid or vermiform phagotrophs, two slightly spiraling rows of around 12 cilia each, thecal plates below the membrane supported by microtubules and rotationally symmetrical, tubular and saccular cristae.[52][60] | 10[62] | |

| Malawimonada | Malawimonas-like organisms | Malawimonads | Small free-living bicilates with two kinetosomes, one or two vanes in posterior cilium. | 3[63] | |

| Metamonada | Middlemonads | Metamonads | Anaerobicormicroaerophilic,some withoutmitochondria;fourkinetosomesperkinetid | ||

| Opisthosporidia (often consideredfungi) |

Opisthokontspores[64] | Parasites withchitinoussporesand extrusive host-invasion apparatus | |||

| Percolozoa | Percolomonas-like animals | Complexlife cyclecontaining amoebae, flagellates andcysts.[52] | |||

| Perkinsozoa | Perkinsus-like animals | Perkinsozoans, perkinsids | Parasitic biflagellates, incomplete apical complex, formation of zoosporangia or undifferentiated cells via a hypha-like tube.[52] | 26 | |

| Provora | Devouring voracious protists[65] | Defined bymolecular phylogeny,free-living eukaryovorous heterotrophic biflagellates with ventral groove and extrusomes.[65] | 7[65] | ||

| Pseudofungi | False fungi | Defined bymolecular phylogeny,phagotrophic heterokonts with a helical ciliary transition zone.[66] | over 1,200[67] | ||

| Retaria | Reticulopodia-bearing organisms[58] | Feeding byreticulopodia(oraxopodia) typically projected through various types of skeleton, closed mitosis.[68] | 10,000extant 50,000 fossil |

||

| Sulcozoa (paraphyletic) |

Groove-bearing animals[59] | Aerobicflagellates (none, 1, 2 or 4 flagella) with dorsal semi-rigid pellicle of one or two submembrane dense layers, ventral feeding groove, branching ventral pseudopodia, typically filose.[59] | 40+ | ||

| Telonemia | Telonema-like organisms[69] | Telonemids[70] | Phagotrophicpyriform biflagellates with a unique complex cytoskeleton, tubular cristae, tripartite mastigonemes, cortical alveoli.[69][70] | 7 | |

| Total: 26,but see below. | |||||

The number of protist phyla varies greatly from one classification to the next. The Catalogue of Life includesRhodophytaandGlaucophytain kingdom Plantae,[50]but other systems consider these phyla part of Protista.[71]In addition, less popular classification schemes uniteOchrophytaandPseudofungiunder one phylum,Gyrista,and all alveolates exceptciliatesin one phylumMyzozoa,later lowered in rank and included in a paraphyletic phylumMiozoa.[51]Even within a phylum, other phylum-level ranks appear, such as the case ofBacillariophyta(diatoms) withinOchrophyta.These differences became irrelevant after the adoption of acladisticapproach by the ISP, where taxonomic ranks are excluded from the classifications after being considered superfluous and unstable. Many authors prefer this usage, which lead to the Chromista-Protozoa scheme becoming obsolete.[52]

Bacteria

editCurrently there are 40 bacterial phyla (not including "Cyanobacteria") that have been validly published according to theBacteriological Code[72]

- Abditibacteriota

- Acidobacteriota,phenotypically diverse and mostly uncultured

- Actinomycetota,High-G+C Gram positive species

- Aquificota,deep-branching

- Armatimonadota

- Atribacterota

- Bacillota,Low-G+C Gram positive species, such as the spore-formersBacilli(aerobic) andClostridia(anaerobic)

- Bacteroidota

- Balneolota

- Bdellovibrionota

- Caldisericota,formerly candidate division OP5,Caldisericum exileis the sole representative

- Calditrichota

- Campylobacterota

- Chlamydiota

- Chlorobiota,green sulphur bacteria

- Chloroflexota,green non-sulphur bacteria

- Chrysiogenota,only 3 genera (Chrysiogenes arsenatis,Desulfurispira natronophila,Desulfurispirillum alkaliphilum)

- Coprothermobacterota

- Deferribacterota

- Deinococcota,Deinococcus radioduransandThermus aquaticusare "commonly known" species of this phyla

- Dictyoglomota

- Elusimicrobiota,formerly candidate division Thermite Group 1

- Fibrobacterota

- Fusobacteriota

- Gemmatimonadota

- Ignavibacteriota

- Kiritimatiellota

- Lentisphaerota,formerly clade VadinBE97

- Mycoplasmatota,notable genus:Mycoplasma

- Myxococcota

- Nitrospinota

- Nitrospirota

- Planctomycetota

- Pseudomonadota,the most well-known phylum, containing species such asEscherichia coliorPseudomonas aeruginosa

- Rhodothermota

- Spirochaetota,species includeBorrelia burgdorferi,which causes Lyme disease

- Synergistota

- Thermodesulfobacteriota

- Thermomicrobiota

- Thermotogota,deep-branching

- Verrucomicrobiota

Archaea

editCurrently there are 2 phyla that have been validly published according to theBacteriological Code[72]

- Nitrososphaerota

- Thermoproteota,second most common archaeal phylum

Other phyla that have been proposed, but not validly named, include:

- "Euryarchaeota",most common archaeal phylum

- "Korarchaeota"

- "Nanoarchaeota",ultra-small symbiotes, single known species

See also

editNotes

edit- ^"Wohl aber ist eine solche reale und vollkommen abgeschlossene Einheit die Summe aller Species, welche aus einer und derselben gemeinschaftlichen Stammform allmählig sich entwickelt haben, wie z. B. alle Wirbelthiere. Diese Summe nennen wir Stamm (Phylon)."

References

edit- ^abMcNeill, J.; et al., eds. (2012).International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code), Adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, July 2011(electronic ed.). International Association for Plant Taxonomy. Archived fromthe originalon 10 October 2020.Retrieved14 May2017.

- ^"Life sciences".The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy(third ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. 2005.Retrieved4 October2008.

Phyla in the plant kingdom are frequently called divisions.

- ^Berg, Linda R. (2 March 2007).Introductory Botany: Plants, People, and the Environment(2 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 15.ISBN9780534466695.Retrieved23 July2012.

- ^Valentine 2004,p. 8.

- ^Haeckel, Ernst (1866).Generelle Morphologie der Organismen[The General Morphology of Organisms] (in German). Vol. 1. Berlin, (Germany): G. Reimer. pp.28–29.

- ^Naik, V. N. (1984).Taxonomy of Angiosperms.Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 27.ISBN9780074517888.

- ^Collins AG, Valentine JW (2001)."Defining phyla: evolutionary pathways to metazoan body plans".Evolution and Development.3:432–442. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 April 2020.Retrieved5 March2013.

- ^Valentine, James W. (2004).On the Origin of Phyla.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 7.ISBN978-0-226-84548-7.

Classifications of organisms in hierarchical systems were in use by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Usually, organisms were grouped according to their morphological similarities as perceived by those early workers, and those groups were then grouped according to their similarities, and so on, to form a hierarchy.

- ^abcdeBudd, G. E.; Jensen, S. (May 2000)."A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla".Biological Reviews.75(2): 253–295.doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00046.x.PMID10881389.S2CID39772232.Archived fromthe originalon 15 September 2019.Retrieved26 May2007.

- ^Rouse, G. W. (2001)."A cladistic analysis of Siboglinidae Caullery, 1914 (Polychaeta, Annelida): formerly the phyla Pogonophora and Vestimentifera".Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.132(1): 55–80.doi:10.1006/zjls.2000.0263.

- ^Pawlowski J, Montoya-Burgos JI, Fahrni JF, Wüest J, Zaninetti L (October 1996)."Origin of the Mesozoa inferred from 18S rRNA gene sequences".Molecular Biology and Evolution.13(8): 1128–32.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025675.PMID8865666.

- ^Budd, G. E. (September 1998). "Arthropod body-plan evolution in the Cambrian with an example from anomalocaridid muscle".Lethaia.31(3): 197–210.doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1998.tb00508.x.

- ^Briggs, D. E. G.;Fortey, R. A.(2005). "Wonderful strife: systematics, stem groups, and the phylogenetic signal of the Cambrian radiation".Paleobiology.31(2 (Suppl)): 94–112.doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0094:WSSSGA]2.0.CO;2.S2CID44066226.

- ^abcdefghijklZhang, Zhi-Qiang (30 August 2013)."Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity in 2013. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)".Zootaxa.3703(1): 5.doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.3.

- ^Felder, Darryl L.; Camp, David K. (2009).Gulf of Mexico Origin, Waters, and Biota: Biodiversity.Texas A&M University Press. p. 1111.ISBN978-1-60344-269-5.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakalamMargulis, Lynn;Chapman, Michael J. (2009).Kingdoms and Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth(4th corrected ed.). London: Academic Press.ISBN9780123736215.

- ^Feldkamp, S. (2002)Modern Biology.Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, USA. (pp. 725)

- ^Han, Jian; Morris, Simon Conway; Ou, Qiang; Shu, Degan; Huang, Hai (2017)."Meiofaunal deuterostomes from the basal Cambrian of Shaanxi (China)".Nature.542(7640): 228–231.Bibcode:2017Natur.542..228H.doi:10.1038/nature21072.ISSN1476-4687.PMID28135722.S2CID353780.

- ^Liu, Yunhuan; Carlisle, Emily; Zhang, Huaqiao; Yang, Ben; Steiner, Michael; Shao, Tiequan; Duan, Baichuan; Marone, Federica; Xiao, Shuhai; Donoghue, Philip C. J. (17 August 2022)."Saccorhytus is an early ecdysozoan and not the earliest deuterostome".Nature.609(7927): 541–546.Bibcode:2022Natur.609..541L.doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05107-z.hdl:1983/454e7bec-4cd4-4121-933e-abeab69e96c1.ISSN1476-4687.PMID35978194.S2CID251646316.

- ^Cannon, J.T.; Vellutini, B.C.; Smith, J.; Ronquist, F.; Jondelius, U.; Hejnol, A. (4 February 2016)."Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa".Nature.530(7588): 89–93.Bibcode:2016Natur.530...89C.doi:10.1038/nature16520.PMID26842059.S2CID205247296.

- ^abCavalier-Smith, Thomas(22 June 2004)."Only Six Kingdoms of Life".Proceedings: Biological Sciences.271(1545): 1251–1262.doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2705.PMC1691724.PMID15306349.

- ^Mauseth 2012,pp. 514, 517.

- ^abCronquist, A.; A. Takhtajan; W. Zimmermann (April 1966). "On the higher taxa of Embryobionta".Taxon.15(4): 129–134.doi:10.2307/1217531.JSTOR1217531.

- ^Chase, Mark W. & Reveal, James L. (October 2009), "A phylogenetic classification of the land plants to accompany APG III",Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society,161(2): 122–127,doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.01002.x

- ^abcMauseth, James D. (2012).Botany: An Introduction to Plant Biology(5th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning.ISBN978-1-4496-6580-7.p. 489

- ^Mauseth 2012,p. 540.

- ^Mauseth 2012,p. 542.

- ^Mauseth 2012,p. 543.

- ^Mauseth 2012,p. 509.

- ^Crandall-Stotler, Barbara; Stotler, Raymond E. (2000). "Morphology and classification of the Marchantiophyta". In A. Jonathan Shaw; Bernard Goffinet (eds.).Bryophyte Biology.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 21.ISBN978-0-521-66097-6.

- ^Mauseth 2012,p. 535.

- ^Wyatt, T.; Wösten, H.; Dijksterhuis, J. (2013). "Advances in Applied Microbiology Chapter 2 - Fungal Spores for Dispersion in Space and Time".Advances in Applied Microbiology.85:43–91.doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-407672-3.00002-2.PMID23942148.

- ^"Classifications of Fungi | Boundless Biology".courses.lumenlearning.com.Retrieved5 May2019.

- ^ab"Archaeal Genetics | Boundless Microbiology".courses.lumenlearning.com.

- ^Holt, Jack R.; Iudica, Carlos A. (1 October 2016)."Blastocladiomycota".Diversity of Life.Susquehanna University.Retrieved29 December2016.

- ^Holt, Jack R.; Iudica, Carlos A. (9 January 2014)."Chytridiomycota".Diversity of Life.Susquehanna University.Retrieved29 December2016.

- ^"Chytridiomycota | phylum of fungi".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved5 May2019.

- ^McConnaughey, M (2014).Physical Chemical Properties of Fungi.doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.05231-4.ISBN9780128012383.

- ^Taylor, Thomas; Krings, Michael; Taylor, Edith (2015). "Fossil Fungi Chapter 4 - Chytridiomycota".Fossil Fungi:41–67.doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-387731-4.00004-9.

- ^Holt, Jack R.; Iudica, Carlos A. (12 March 2013)."Microsporidia".Diversity of Life.Susquehanna University.Retrieved29 December2016.

- ^Holt, Jack R.; Iudica, Carlos A. (23 April 2013)."Neocallimastigomycota".Diversity of Life.Susquehanna University.Retrieved29 December2016.

- ^ab"Types of Fungi".BiologyWise.22 May 2009.Retrieved5 May2019.

- ^Wang, Xuewei; Liu, Xingzhong; Groenewald, Johannes Z. (2017)."Phylogeny of anaerobic fungi (phylum Neocallimastigomycota), with contributions from yak in China".Antonie van Leeuwenhoek.110(1): 87–103.doi:10.1007/s10482-016-0779-1.PMC5222902.PMID27734254.

- ^abHibbett DS, Binder M, Bischoff JF, Blackwell M, Cannon PF, Eriksson OE, et al. (May 2007)."A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi"(PDF).Mycological Research.111(Pt 5): 509–47.CiteSeerX10.1.1.626.9582.doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004.PMID17572334.S2CID4686378.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 26 March 2009.

- ^abRuggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; et al. (29 April 2015)."A Higher Level Classification of All Living Organisms".PLOS ONE.10(6): e0119248.Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248.PMC4418965.PMID25923521.

- ^White, Merlin M.; James, Timothy Y.; O'Donnell, Kerry; et al. (November–December 2006). "Phylogeny of the Zygomycota Based on Nuclear Ribosomal Sequence Data".Mycologia.98(6): 872–884.doi:10.1080/15572536.2006.11832617.PMID17486964.S2CID218589354.

- ^Hagen, Joel B. (January 2012)."Five Kingdoms, More or Less: Robert Whittaker and the Broad Classification of Organisms".BioScience.62(1): 67–74.doi:10.1525/bio.2012.62.1.11.

- ^Blackwell, Will H.; Powell, Martha J. (June 1999)."Reconciling Kingdoms with Codes of Nomenclature: Is It Necessary?".Systematic Biology.48(2): 406–412.doi:10.1080/106351599260382.PMID12066717.

- ^Davis, R. A. (19 March 2012)."Kingdom PROTISTA".College of Mount St. Joseph.Retrieved28 December2016.

- ^ab"Taxonomic tree".Catalogue of Life.23 December 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 1 August 2021.Retrieved28 December2016.

- ^abCavalier-Smith T (2022)."Ciliary transition zone evolution and the root of the eukaryote tree: implications for opisthokont origin and classification of kingdoms Protozoa, Plantae, and Fungi".Protoplasma.259:487–593.doi:10.1007/s00709-021-01665-7.PMC9010356.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopAdl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Agatha S, Berney C, Brown MW, Burki F, Cárdenas P, Čepička I, Chistyakova L, del Campo J, Dunthorn M, Edvardsen B, Eglit Y, Guillou L, Hampl V, Heiss AA, Hoppenrath M, James TY, Karnkowska A, Karpov S, Kim E, Kolisko M, Kudryavtsev A, Lahr DJG, Lara E, Le Gall L, Lynn DH, Mann DG, Massana R, Mitchell EAD, Morrow C, Park JS, Pawlowski JW, Powell MJ, Richter DJ, Rueckert S, Shadwick L, Shimano S, Spiegel FW, Torruella G, Youssef N, Zlatogursky V, Zhang Q (2019)."Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes".Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology.66(1): 4–119.doi:10.1111/jeu.12691.PMC6492006.PMID30257078.

- ^abPawlowski J, Audic S, Adl S, Bass D, Belbahri L, Berney C, et al. (6 November 2012)."CBOL protist working group: barcoding eukaryotic richness beyond the animal, plant, and fungal kingdoms".PLOS Biology.10(11): e1001419.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001419.PMC3491025.PMID23139639.

- ^abVotýpka J, Modrý D, Oborník M, Šlapeta J, Lukeš J (2016). "Apicomplexa". In Archibald J, Simpson AGB, Slamovits CH, Margulis L, Melkonian M, Chapman DJ, Corliss JO (eds.).Handbook of the Protists.Cham: Springer.doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32669-6_20-1.

- ^Jan Janouškovec; Denis Tikhonenkov; Fabien Burki; Alexis T Howe; Martin Kolísko; Alexander P Mylnikov;Patrick John Keeling(25 February 2015)."Factors mediating plastid dependency and the origins of parasitism in apicomplexans and their close relatives".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.112(33): 10200–10207.Bibcode:2015PNAS..11210200J.doi:10.1073/PNAS.1423790112.ISSN0027-8424.PMC4547307.PMID25717057.WikidataQ30662251.

- ^abcdefMichael D. Guiry(21 January 2024). "How many species of algae are there? A reprise. Four kingdoms, 14 phyla, 63 classes and still growing".Journal of Phycology.00:1–15.doi:10.1111/JPY.13431.ISSN0022-3646.PMID38245909.WikidataQ124684077.

- ^Foissner, W.; Hawksworth, David, eds. (2009).Protist Diversity and Geographical Distribution.Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation. Vol. 8. Springer Netherlands. p. 111.doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2801-3.ISBN9789048128006.

- ^abcT Cavalier-Smith (March 2002). "The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa".International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology.52(2): 297–354.doi:10.1099/00207713-52-2-297.ISSN1466-5026.PMID11931142.WikidataQ28212529.

- ^abcdCavalier-Smith T (2013). "Early evolution of eukaryote feeding modes, cell structural diversity, and classification of the protozoan phyla Loukozoa, Sulcozoa, and Choanozoa".European Journal of Protistology.49(2): 115–178.doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2012.06.001.PMID23085100.

- ^abW Foissner; H Blatterer; I Foissner (1 October 1988). "The hemimastigophora (Hemimastix amphikineta nov. gen., nov. spec.), a new protistan phylum from gondwanian soils".European Journal of Protistology.23(4): 361–383.doi:10.1016/S0932-4739(88)80027-0.ISSN0932-4739.PMID23195325.WikidataQ85570914.

- ^Gordon Lax; Yana Eglit; Laura Eme; Erin M Bertrand;Andrew J Roger;Alastair G B Simpson (14 November 2018). "Hemimastigophora is a novel supra-kingdom-level lineage of eukaryotes".Nature.564(7736): 410–414.doi:10.1038/S41586-018-0708-8.ISSN1476-4687.PMID30429611.WikidataQ58834974.

- ^Shɨshkin, Yegor (2022). "Spironematella terricolacomb. n. andSpironematella goodeyicomb. n. (Hemimastigida = Hemimastigea = Hemimastigophora) forSpironema terricolaandSpironema goodeyiwith diagnoses of the genus and family Spironematellidae amended ".Zootaxa.5128(2): 295–297.doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5128.2.8.PMID36101172.S2CID252220401.

- ^Heiss AA, Warring SD, Lukacs K, Favate J, Yang A, Gyaltshen Y, Filardi C, Simpson AGB, Kim E (December 2020). "Description of Imasa heleensis, gen. nov., sp. nov. (Imasidae, fam. nov.), a Deep-Branching Marine Malawimonad and Possible Key Taxon in Understanding Early Eukaryotic Evolution".Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology.68:e12837.doi:10.1111/jeu.12837.

- ^Karpov, Sergey; Mamkaeva, Maria A.; Aleoshin, Vladimir; Nassonova, Elena; Lilje, Osu; Gleason, Frank H. (1 January 2014)."Morphology, phylogeny, and ecology of the aphelids (Aphelidea, Opisthokonta) and proposal for the new superphylum Opisthosporidia".Frontiers in Microbiology.5:112.doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00112.PMC3975115.PMID24734027.

- ^abcDenis V. Tikhonenkov, Kirill V. Mikhailov, Ryan M. R. Gawryluk, Artem O. Belyaev, Varsha Mathur, Sergey A. Karpov, Dmitry G. Zagumyonnyi, Anastasia S. Borodina, Kristina I. Prokina, Alexander P. Mylnikov, Vladimir V. Aleoshin & Patrick J. Keeling (7 December 2022). "Microbial predators form a new supergroup of eukaryotes".Nature.612:714–719.doi:10.1038/S41586-022-05511-5.ISSN1476-4687.WikidataQ115933632.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Thomas Cavalier-Smith;Ema E-Y Chao (April 2006). "Phylogeny and megasystematics of phagotrophic heterokonts (kingdom Chromista)".Journal of Molecular Evolution.62(4): 388–420.doi:10.1007/S00239-004-0353-8.ISSN0022-2844.PMID16557340.WikidataQ28303534.

- ^Thines M (2018)."Oomycetes".Current Biology.28(15): R812–R813.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.062.

- ^T Cavalier-Smith (1999). "Principles of protein and lipid targeting in secondary symbiogenesis: euglenoid, dinoflagellate, and sporozoan plastid origins and the eukaryote family tree".Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology.46(4): 347–66.doi:10.1111/J.1550-7408.1999.TB04614.X.ISSN1066-5234.PMID18092388.WikidataQ28261633.

- ^abShalchian-Tabrizi, K; Eikrem, W; Klaveness, D; Vaulot, D; Minge, M.A; Le Gall, F; Romari, K; Throndsen, J; Botnen, A; Massana, R; Thomsen, H.A; Jakobsen, K.S (28 April 2006)."Telonemia, a new protist phylum with affinity to chromist lineages".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.273(1595): 1833–1842.doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3515.PMC1634789.PMID16790418.

- ^abTikhonenkov, Denis V.; Jamy, Mahwash; Borodina, Anastasia S.; Belyaev, Artem O.; Zagumyonnyi, Dmitry G.; Prokina, Kristina I.; Mylnikov, Alexander P.; Burki, Fabien; Karpov, Sergey A. (2022)."On the origin of TSAR: morphology, diversity and phylogeny of Telonemia".Open Biology.12(3). The Royal Society.doi:10.1098/rsob.210325.ISSN2046-2441.PMC8924772.PMID35291881.

- ^Corliss, John O. (1984). "The Kingdom Protista and its 45 Phyla".BioSystems.17(2): 87–176.doi:10.1016/0303-2647(84)90003-0.PMID6395918.

- ^abEuzéby JP, Parte AC."Names of phyla".List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature(LPSN).Retrieved3 April2022.