Renal colic,also known asureteric colic,is a type ofabdominal paincommonly caused by obstruction ofureterfrom dislodgedkidney stones.The most frequent site of obstruction is the vesico-ureteric junction (VUJ), the narrowest point of theupper urinary tract.Acute obstruction and the resultant urinary stasis (disruption ofurineflow) can distend the ureter (hydroureter) and cause areflexiveperistalticsmooth musclespasm,which leads to a very intensevisceral paintransmitted via theureteric plexus.

| Renal colic | |

|---|---|

| |

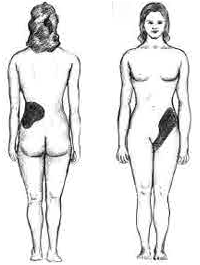

| Localization of pain caused by kidney stones | |

| Specialty | Urology |

| Complications | Acute kidney injury |

Signs and symptoms

editRenalcolictypically begins in theflankand often radiates to below the ribs or thegroin.It typically comes in waves due touretericperistalsis,but may be constant. It is often described as one of the most severe pains.[1]

Although this condition can be very painful, most ureteric stones under 5 mm size will eventually pass into the bladder without needing treatments, and cause no permanent physical damage. The experience is said to be traumatizing due to the severe pain, and the experience ofpassing blood and clotsas well as pieces of stone. In most cases, people with renal colic are advised to drink more water to facilitate passing; in other instances,lithotripsyorendoscopic surgerymay be needed. Preventive treatment can be instituted to minimize the likelihood of recurrence.[2]

Diagnosis

editThe diagnosis of renal colic is the same as the diagnosis for renal calculus and ureteric stones.[citation needed]

Differential diagnosis

editA renal colic must be differentiated from the following conditions:[3]

- biliary colicandcholecystitis

- aorticand iliacaneurysms(in older patients with left-side pain, hypertension or atherosclerosis)

- interstitial:appendicitis,diverticulitisorperitonitis(in this case patients prefer to lie still rather than being restless[3])

- gynaecological:endometriosis,ovarian torsionandectopic pregnancy

- testicular torsion

Treatment

editMost small stones are passed spontaneously and onlypain managementis required. Above 5 mm (0.20 in) the rate of spontaneous stone passage decreases.[4]NSAIDs(non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), such asdiclofenac[5]oribuprofen,andantispasmodicslikebutylscopolamineare used. Althoughmorphinemay be administered to assist with emergency pain management, it is often not recommended as morphine is addictive and raises ureteral pressure, worsening the condition. Vomiting is also considered an important adverse effect of opioids, mainly withpethidine.[6]Oral narcotic medications are also often used.[citation needed]

There is typically noantalgicposition for the patient (lying down on the non-aching side and applying a hot bottle or towel to the area affected may help). Larger stones may require surgical intervention for their removal, such asshockwave lithotripsy,laser lithotripsy,ureteroscopyorpercutaneous nephrolithotomy.Patients can also be treated withalpha blockers[7]in cases where the stone is located in theureter.

A 2019 review found three cases of renal colic werehydronephrosiscaused by malpositionedmenstrual cupspressing on a ureter. When the cups were removed, the symptoms disappeared.[8]

References

edit- ^Nephrolithiasis~OverviewateMedicine§ Background.

- ^"eMedicine - Nephrolithiasis: Acute Renal Colic: Article by Stephen W Leslie".Retrieved2008-01-01.

- ^ab"Managing patients with renal colic in primary care - BPJ 60 April 2014".bpac.org.nz.Retrieved2019-01-26.

- ^Ordon, Michael; Andonian, Sero; Blew, Brian; Schuler, Trevor; Chew, Ben; Pace, Kenneth T. (2015-01-01)."CUA Guideline: Management of ureteral calculi".Canadian Urological Association Journal.9(11–12):E837 –E851.doi:10.5489/cuaj.3483.ISSN1911-6470.PMC4707902.PMID26788233.

- ^Teece, DD (2006)."Intravenous NSAID's in the management of renal colic: Article by Debasis Das".Emergency Medicine Journal.23(3):224–225.doi:10.1136/emj.2005.034330.PMC2464448.PMID16498166.

- ^Holdgate, A; Pollock, T (18 April 2005)."Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(2): CD004137.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004137.pub3.PMC6986698.PMID15846699.

- ^Lipkin, Michael; Shah, Ojas (2006-01-01)."The Use of Alpha-Blockers for the Treatment of Nephrolithiasis".Reviews in Urology.8(Suppl 4):S35 –S42.ISSN1523-6161.PMC1765041.PMID17216000.

- ^Eijk, Anna Maria van; Zulaika, Garazi; Lenchner, Madeline; Mason, Linda; Sivakami, Muthusamy; Nyothach, Elizabeth; Unger, Holger;Laserson, Kayla;Phillips-Howard, Penelope A. (2019-08-01)."Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability: a systematic review and meta-analysis".The Lancet Public Health.4(8):e376 –e393.doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30111-2.ISSN2468-2667.PMC6669309.PMID31324419.