Sarepta(near modernSarafand,Lebanon) was aPhoeniciancity on theMediterraneancoast betweenSidonandTyre,also known biblically asZarephath.It became a bishopric, which faded, and remains a double (Latin and Maronite) Catholictitular see.

| |

| Location | Lebanon |

|---|---|

| Region | South Governorate |

| Coordinates | 33°27′27″N35°17′45″E/ 33.45750°N 35.29583°E |

Most of the objects by which Phoenician culture is characterised are those that have been recovered scattered among Phoenician colonies and trading posts; such carefully excavated colonial sites are inSpain,Sicily,SardiniaandTunisia.The sites of many Phoenician cities, like Sidon and Tyre, by contrast, are still occupied, unavailable to archaeology except in highly restricted chance sites, usually much disturbed. Sarepta[1]is the exception, the one Phoenician city in the heartland of the culture that has been unearthed and thoroughly studied.

History

editSarepta is mentioned for the first time in the voyage of an Egyptian in the 14th century BCE.[2]Obadiahsays it was the northern boundary ofCanaan:“And the exiles of this host of the sons of Israel who are among the Canaanites as far asZarephath(Heb. צרפת), and the exiles of Jerusalem who are in Sepharad, will possess the cities of the south.”[3]The medieval lexicographer, David ben Abraham Al-Alfāsī, identifiesZarephathwith the city of Ṣarfend (Judeo-Arabic: צרפנדה).[4]Originally Sidonian, the town passed to the Tyrians after the invasion ofShalmaneser IV,722 BCE. It fell toSennacheribin 701 BCE.

The firstBooks of Kings(17:8-24) describes the city as being subject to Sidon in the time ofAhab,and says that the prophetElijah,after leaving the brookCherith,multiplied the meal and oil of thewidow of Zarephath(Sarepta) andresurrectedher son, an incident also referred to byJesusinLuke's Gospel.[5]

Zarephath (צרפת ṣārĕfáṯ, tsarfát; Σάρεπτα, Sárepta) in Hebrew became theeponymfor anysmelterorforge,ormetalworkingshop. In the 1st century CE, the Roman Sarepta, a port about 1 km (0.62 mi) to the south[6]is mentioned byJosephus[7]and byPliny the Elder.[8]

Sarepta is the location of a Shia shrine toAbu Dhar al-Ghifari,a Companion ofMuhammad.The shrine is believed to have been built at least several centuries after Abu Dhar's death.[9]

After the Islamization of the area, in 1185, theGreekmonkPhocas, making a gazetteer of theHoly Land(De locis sanctis,7), found the town almost in its ancient condition. A century later, according toBurchard of Mount Sion,it was in ruins and contained only seven or eight houses.[10]Even after theCrusader stateshad collapsed, theRoman Catholic Churchcontinued to appoint purelytitular bishopsof Sarepta, the most noted being Thomas of Wroclaw who held the post from 1350 until 1378.[11]

Ecclesiastical history

editThis sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(April 2021) |

Sarepta as a Christian city was mentioned in theItinerarium Burdigalense;theOnomasticonofEusebiusand inJerome;by Theodosius and Pseudo-Antoninus who, in the 6th century call it a small town but very Christian.[12]It contained at that time a church dedicated to St. Elias (Elijah). TheNotitia episcopatuum,a list of bishoprics made in Antioch in the 6th century, speaks of Sarepta as a suffragansee of Tyre;all of its bishops are unknown.

Titular sees

editThe diocese was nominally restored astitular see,twice: in Latin and Maronite (Eastern Catholic) traditions.

Sarepta of the Maronites

editThistitular bishopricwas established in 1983.

It has had the following incumbents of the fitting episcopal (lowest) rank:

- Emile Eid (1982.12.20 – death 2009.11.30), in theRoman Curia:Vice-President ofPontifical Commission for the Revision of Code of Oriental Canon Law(1982.12.20 – 1990.10.18) and on emeritate; previouslyDefender of the BondofSupreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura(1969? – 1974),Promoter of Justiceof the same Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura (1969 – 1980)

- Hanna G. Alwan,Congregation of the Lebanese Maronite Missionaries(L.M.) (2011.08.13 –...),Bishop of Curiaof the Maronites at the Patriarchate of Antioc; previouslyPrelate AuditorofTribunal of the Roman Rota(1996.03.04 – 2011.08.13).

Sarepta of the Romans

editIt was established as titular bishopric no later than the 15th century. It has been vacant for decades, having had the following incumbents:

- Theodorich, (around 1350), asAuxiliary BishopofRoman Catholic Diocese of Olomouc(Moravia)

- Jaroslav of Bezmíře,appointed Bishop of Sarepta on 1394.7.15 byPope Boniface IX[13]

- Guillaume Vasseur,Dominican Order(O.P.) (1448.10.23 – death 1476?), no actual prelature

- Gilles Barbier,Friars Minor(O.F.M.) (1476.04.03 – death 1494.03.28) asAuxiliary BishopofDiocese of Tournai(Belgium) (1476.04.03 – 1494.03.28)

- Nicolas Bureau, O.F.M. (1519.12.02 – death 1551) as Auxiliary Bishop ofDiocese of Tournai(Belgium) (1519.12.02 – 1551)

- Guillaume Hanwere (1552.04.27 – 1560) as Auxiliary Bishop of above Tournai (Belgium) (1552.04.27 – 1560)

- Johannes Kaspar Stredele 'Austrian) (1631.12.15 – death 1642.12.28) as Auxiliary Bishop ofDiocese of Passau(Bavaria,Germany) (1631.12.15 – 1642.12.28)

- Wojciech Ignacy Bardziński (1709.01.28 – death 1722?) as Auxiliary Bishop ofDiocese of Kujawy–Pomorze(Poland) (1709.01.28 – 1722?)

- Charles-Antoine de la Roche-Aymon(1725.06.11 – 1730.10.02) as Auxiliary Bishop ofDiocese of Limoges(France) (1725.06.11 – 1730.10.02); later Bishop ofTarbes(France) ([1729.12.27] 1730.10.02 – 1740.11.11), Metropolitan Archbishop ofToulouse(France) ([1740.01.10] 1740.11.11 – 1752.12.18), Metropolitan Archbishop ofNarbonne(France) ([1752.10.02] 1752.12.18 – 1763.01.24), Metropolitan Archbishop ofReims(France) ([1762.12.05] 1763.01.24 – death 1777.10.27), createdCardinal-Priestwith no Title assigned (1771.12.16 – 1777.10.27)

- Johann Anton Wallreuther (1731.03.05 – 1734.01.16) as Auxiliary Bishop ofDiocese of Worms(Germany) (1731.03.05 – 1734.01.16)

- Jean de Cairol de Madaillan (1760.01.28 – 1770.01.29) as Auxiliary Bishop ofArchdiocese of Narbonne(France) (1760.01.28 –?); later Bishop ofVence(France) (1770.01.29 – 1771.12.16), Bishop ofGrenoble(France) (1771.12.16 [1772.01.23] – 1779.12.10)

- Jean-Denis de Vienne (1775.12.18 – death 1800) as Auxiliary Bishop ofLyon(France) (1775.12.18 – 1800)

- Alois Jozef Krakowski von Kolowrat (1800.12.22 – 1815.03.15) as Auxiliary Bishop ofArchdiocese of Olomouc(Olomütz,Moravia,now Czech Republic) (1800.12.22 – 1815.03.15), Bishop ofHradec Králové(now Czech Republic) (1815.03.15 – 1831.02.28), Metropolitan Archbishop ofArchdiocese of Praha(Prague,Bohemia,now Czech Republic) (1831.02.28 – death 1833.03.28)

- Johann Heinrich Milz (1825.12.19 – death 1833.04.29) as Auxiliary Bishop ofTrier(Germany) (1825.12.19 – 1833.04.29)

- Johann Stanislaus Kutowski (1836.02.01 – death 1848.12.29) as Auxiliary Bishop ofDiocese of Chełmno(Kulm, Poland) (1836.02.01 – 1848.12.29)

- Franz Xaver Zenner (1851.02.17 – death 1861.10.29) as Auxiliary Bishop ofArchdiocese of Wien(Vienna, Austria) (1851.02.17 – 1861.10.29)

- Nicholas Power (1865.04.30 – death 1871.04.05) asCoadjutor BishopofKillaloe(Ireland) (1865.04.30 – 1871.04.05)

- Jean-François Jamot (1874.02.03 – 1882.07.11) as onlyApostolic VicarofNorthern Canada(Canada) (1874.02.03 – 1882.07.11); next (see) promoted first Bishop ofPeterborough(Canada) (1882.07.11 – death 1886.05.04)

- Antonio Scotti (1882.09.25 – 1886.01.15) as Auxiliary Bishop ofArchdiocese of Benevento(Italy) (1882.09.25 – 1886.01.15); next Bishop ofAlife(Italy) (1886.01.15 – retired 1898.03.24), emeritate as Titular Bishop ofTiberiopolis(1898.03.24 – death 1919.06.10)

- Paulus Palásthy (1886.05.04 – death 1899.09.24) as Auxiliary Bishop ofArchdiocese of Esztergom(Hungary) (1886.05.04 – 1899.09.24)

- Filippo Genovese (Italian) (1900.12.17 – death 1902.12.16), no actual prelature

- Joseph Müller (1903.04.30 – death 1921.03.21) as Auxiliary Bishop ofArchdiocese of Köln(Cologne, Germany) (1903.04.30 – 1921.03.21)

- Edward Doorly (1923.04.05 – 1926.07.17) as Coadjutor Bishop ofElphin(Ireland) (1923.04.05 – succession 1926.07.17); next Bishop of Elphin (1926.07.17 – 1950.04.05)

- Petar Dujam Munzani (1926.08.13 – 1933.03.16) asApostolic AdministratorofArchdiocese of Zadar(Croatia) (1926.08.13 – succession 1933.03.16); later Archbishop of Zadar (Croatia) (1933.03.16 – retired 1948.12.11), emeritate as Titular Archbishop ofTyana(1948.12.11 – death 1951.01.28)

- François-Louis Auvity(1933.06.02 – 1937.08.14) as Auxiliary Bishop ofArchdiocese of Bourges(France) (1933.06.02 – 1937.08.14); later Bishop ofMende(France) (1937.08.14 – retired 1945.09.11), emeritate as Titular Bishop ofDionysiana(1945.09.11 – death 1964.02.15)

- Francesco Canessa (1937.09.04 – 1948.01.14)

- John Francis Dearden(later Cardinal) (1948.03.13 – 1950.12.22)

- Athanasios Cheriyan Polachirakal (1953.12.31 – 1955.01.27)

- Luis Andrade Valderrama,Friars Minor(O.F.M.) (1955.03.09 – 1977.06.29)

Archaeology

editAHeavy Neolithicarchaeological site of theQaraoun culturethat pre-dated Sarepta by several thousand years was discovered at Sarafand byHajji Khalaf.He made a collection of material and passed it to theNational Museum of Beirut.It consisted of anassemblageof large flakes andbifacesinEoceneflint.Somepiebaldflint blades were also found along withhammerstonesinNummuliticlimestonethat resemble finds fromAadloun II(Bezez Cave), which is located 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) to the South. Khalaf also found a well-madeadzeand a narrow, slightly polishedchisel.A collection in the National Museum of Beirut marked "Jezzine ou Sarepta" consisted of around twelve neatly madediscoid- andtortoise-cores incherty flintof a cream colour with a tinge of red.[14]

The lowtellon the seashore was excavated byJames B. Pritchardover five years from 1969 to 1974. [15] [16] Civil war in Lebanon put an end to the excavations.

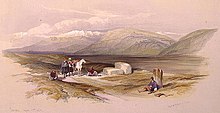

The site of the ancient town is marked by theruinson the shore to the south of the modern village, about eight miles to the south of Sidon, which extend along the shore for a mile or more. They are in two distinct groups, one on a headland to the west of a fountain called ‛Ain el-Ḳantara, which is not far from the shore. Here was the ancient harbor which still affords shelter for small craft. The other group of ruins, to the south, consists ofcolumns,sarcophagiand marble slabs, indicating a city of considerable importance.

Pritchard's excavations revealed many artifacts of daily life in the ancient Phoenician city of Sarepta: pottery workshops andkilns,artifacts of daily use and religious figurines, numerous inscriptions that included some inUgaritic.Pillar worshipis traceable from an 8th-century shrine ofTanit-Ashtart,and a seal with the city's name made the identification secure. The local Bronze Age-Iron Age stratigraphy was established in detail; absolute dating depends in part on correlations with Cypriote and Aegean stratigraphy.

The climax of the Sarepta discoveries at Sarafand is the cult shrine of "Tanit/Astart",who is identified in the site by an inscribed votive ivory plaque, the first identification of Tanit in her homeland. The site revealed figurines, further carved ivories,amuletsand a cultic mask.[17]

Other uses of the name

editInHebrewafter theDiaspora,the nameצרפת,ts-r-f-t,Tsarfat(Zarephath) is used to meanFrance,perhaps because the Hebrew lettersts-r-f,if reversed, becomef-r-ts.[18]That usage is retained in daily use in contemporary Hebrew.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^Identification of the site is secured by inscriptions that include a stamp-seal with the name of Sarepta.

- ^Chabas,Voyage d'un Egyptien,1866, pp 20, 161, 163

- ^Obadiah 1:20

- ^The Hebrew-Arabic Dictionary known as "Kitāb Jāmi' Al-Alfāẓ (Agron)," p. xxxviii, pub. by Solomon L. Skoss, 1936 Yale University

- ^Luke 4:26

- ^Designated Area I, it was excavated in 1969-70.

- ^Antiquities of the Jews,Book VIII, 13:2

- ^Natural History,Book V, 17

- ^Rihan, Mohammad (2014).The Politics and Culture of an Umayyad Tribe: Conflict and Factionalism in the Early Islamic Period.Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 195.ISBN9780857736208– via books.google.com.

- ^Monachus Borchardus, Descriptio Terrae sanctae, et regionum finitarum, vol. 2, pp. 9, 1593

- ^Piotr Górecki, Parishes, Tithes and Society in Earlier Medieval Poland c. 1100-c. 1250, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. i-ix+1-146, 1993

- ^Geyer,Intinera hierosolymitana,Vienna, 1898, 18, 147, 150

- ^"Inkvizitoři v Českých zemích v době předhusitské"(PDF).p. 63.Retrieved13 March2021.

- ^Lorraine Copeland; P. Wescombe (1965).Inventory of Stone-Age sites in Lebanon, pp. 95 & 135.Imprimerie Catholique. Archived fromthe originalon 24 December 2011.Retrieved21 July2011.

- ^James B. Pritchard, SAREPTA. A Preliminary Report on the Iron Age. Excavations of the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, 1970-72. With contributions by William P. Anderson; Ellen Herscher; Javier Teixidor, University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 1975,ISBN0-934718-24-5

- ^James B. Pritchard, Sarepta in History and Tradition, in J. Reumann (ed.). Understanding the Sacred Text: Essays in honor of Morton S. Enslin on the Hebrew Bible and Christian beginnings, pp. 101-114, Judson Press, 1972,ISBN0-8170-0487-4

- ^Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia. “Two Phoenician Inscriptions Carved in Ivory: Again the Ur Box and the Sarepta Plaque.” Orientalia 59, no. 1 (1990): 58–66.http://www.jstor.org/stable/43075770.

- ^Banitt, Menahem (1985).Rashi, interpreter of the biblical letter.Tel Aviv: Chaim Rosenberg School of Jewish Studies. p. 141.OCLC15252529.Retrieved1 January2013.

Sources

edit- Pritchard, James B.Recovering Sarepta, a Phoenician City: Excavations at Sarafund, 1969-1974, University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania(Princeton: Princeton University Press) 1978,ISBN0-691-09378-4

- William P. Anderson, Sarepta I: The late bronze and Iron Age strata of area II.Y: the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania excavations at Sarafand, Lebanon (Publications de l'Universite libanaise), Département des publications de l'Universite Libanaise, 1988

- Issam A. Khalifeh, Sarepta II: The Late Bronze and Iron Age Periods of Area Ii.X, University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, 1988,ISBN99943-751-5-6

- Robert Koehl, Sarepta III: the Imported Bronze & Iron Age, University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, 1985,ISBN99943-751-7-2

- James B. Pritchard, Sarepta IV: The Objects from Area Ii.X, University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, 1988,ISBN99943-751-9-9

- Lloyd W. Daly, A Greek-Syllabic Cypriot Inscription from Sarafand, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bd. 40, pp. 223–225, 1980

- Dimitri Baramki,A Late Bronze Age tomb at Sarafend, ancient Sarepta, Berytus, vol. 12, pp. 129–42, 1959

- Charles Cutler Torrey, The Exiled God of Sarepta, Berytus, vol. 9, pp. 45–49, 1949