Tranylcypromine,sold under the brand nameParnateamong others,[1]is amonoamine oxidase inhibitor(MAOI).[4][7]More specifically, tranylcypromine acts asnonselectiveandirreversibleinhibitorof theenzymemonoamine oxidase(MAO).[4][7]It is used as anantidepressantandanxiolyticagent in theclinicaltreatmentofmoodandanxiety disorders,respectively. It is also effective in the treatment ofADHD.[8][9]

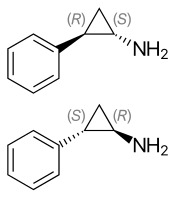

(1S,2R)-(−)-tranylcypromine (top), (1R,2S)-(+)-tranylcypromine (bottom) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Parnate, many generics[1] |

| Other names | trans-2-Phenylcyclopropylamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682088 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokineticdata | |

| Bioavailability | 50%[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver[5][6] |

| Eliminationhalf-life | 2.5 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Urine,Feces[4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChemCID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.312 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H11N |

| Molar mass | 133.194g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

Tranylcypromine is also known astrans-2-phenylcyclopropyl-1-amine and is formedpro formafrom thecyclizationofamphetamine'sisopropylamineside chain.As a result, it is classifiedstructurallyas asubstituted phenethylamineandamphetamine.

Medical uses

editTranylcypromine is used to treatmajor depressive disorder,includingatypical depression,especially when there is ananxiety component,typically as a second-line treatment.[10]It is also used in depression that is not responsive toreuptake inhibitorantidepressants, such as theSSRIs,TCAs,orbupropion.[11]In addition to being a recognized treatment for major depressive disorder, tranylcypromine has been demonstrated to be effective in treating obsessive compulsive disorder[12][13][14]andpanic disorder.[15][16]

Systematic reviewsandmeta-analyseshave reported that tranylcypromine is significantly more effective in the treatment of depression thanplaceboand has efficacy over placebo similar to that of other antidepressants such astricyclic antidepressants.[17][18]

Contraindications

editContraindications include:[10][11][19]

- Porphyria

- Cardiovascularorcerebrovascular disease

- Pheochromocytoma

- Tyramine,found in several foods, is metabolized by MAO. Ingestion and absorption of tyramine causes extensive release ofnorepinephrine,which can rapidly increase blood pressure to the point of causinghypertensive crisis.

- Concomitant use of serotonin-enhancing drugs, includingSSRIs,serotonergicTCAs,dextromethorphan,andmeperidinemay causeserotonin syndrome.

- Concomitant use ofMRAs,includingfenfluramine,amphetamine,andpseudoephedrinemay cause toxicity via serotonin syndrome orhypertensive crisis.

- L-DOPAgiven withoutcarbidopamay cause hypertensive crisis.

Dietary restrictions

editTyramineis a biogenic amine produced as a (generally undesirable) byproduct during the fermentation of certain tyrosine-rich foods. It is rapidly metabolized byMAO-Ain those not taking MAO-inhibiting drugs. Individuals sensitive to tyramine-induced hypertension may experience an uncomfortable, yet fleeting, increase in blood pressure after ingesting relatively small amounts of tyramine.[20][19][21]

Advances in food safety standards in most nations, as well as the widespread use of starter-cultures shown to result in undetectable to low levels of tyramine in fermented products has rendered concerns of serious hypertensive crises rare in those consuming a modern diet.[22][21]Those treated with MAOIs should still exercise caution, particularly at home, if it is unclear whether food has been properly refrigerated. Since tyramine-producing microbes also produce compounds to which humans have a natural aversion, disposal of any questionable food—particularly meats—should be sufficient to avoid hypertensive crises.

Adverse effects

editIncidence of adverse effects[17]

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Dizziness secondary toorthostatic hypotension(17%)

Common (1-10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Tachycardia(5–10%)

- Hypomania(7%)

- Paresthesia(5%)

- Weight loss (2%)

- Confusion (2%)

- Dry mouth(2%)

- Sexual function disorders (2%)

- Hypertension(1–2 hours after ingestion) (2%)

- Rash (2%)

- Urinary retention(2%)

Other (unknown incidence) adverse effects include:

- Increased/decreased appetite

- Blood dyscrasias

- Chest pain

- Diarrhea

- Edema

- Hallucinations

- Hyperreflexia

- Insomnia

- Jaundice

- Leg cramps

- Myalgia

- Palpitations

- Sensation of cold

- Suicidal ideation

- Tremor

Of note, there has not been found to be a correlation between sex and age below 65 regarding incidence of adverse effects.[17]

Tranylcypromine is not associated withweight gainand has a low risk for hepatotoxicity compared to thehydrazineMAOIs.[17][11]

It is generally recommended that MAOIs be discontinued prior toanesthesia;however, this creates a risk of recurrent depression. In a retrospective observational cohort study, patients on tranylcypromine undergoing general anesthesia had a lower incidence of intraoperative hypotension, while there was no difference between patients not taking an MAOI regarding intraoperative incidence ofbradycardia,tachycardia, or hypertension.[23]The use of indirectsympathomimetic drugsor drugs affecting serotonin reuptake, such asmeperidineordextromethorphanposes a risk forhypertensionandserotonin syndromerespectively; alternative agents are recommended.[24][25]Other studies have come to similar conclusions.[17]Pharmacokinetic interactions with anesthetics are unlikely, given that tranylcypromine is a high-affinity substrate forCYP2A6and does not inhibit CYP enzymes at therapeutic concentrations.[20]

Tranylcypromineabusehas been reported at doses ranging from 120 to 600 mg per day.[10][26][17]It is thought that higher doses have moreamphetamine-like effects and abuse is promoted by the fast onset and short half-life of tranylcypromine.[17]

Cases of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviours have been reported during tranylcypromine therapy or early after treatment discontinuation.[10]

Symptoms of tranylcypromine overdose are generally more intense manifestations of its usual effects.[10]

Interactions

editIn addition to contraindicated concomitant medications, tranylcypromine inhibitsCYP2A6,which may reduce the metabolism and increase the toxicity of substrates of this enzyme, such as:[19]

- Dexmedetomidine

- nicotine

- TSNAs(found in cured tobacco products, includingcigarettes)

- Valproate

Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitorsprevent neuronal uptake oftyramineand may reduce itspressoreffects.[19]

Pharmacology

editPharmacodynamics

editTranylcypromine acts as a nonselective and irreversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase.[4]Regarding theisoformsof monoamine oxidase, it shows slight preference for theMAOBisoenzymeoverMAOA.[20]This leads to an increase in the availability ofmonoamines,such asserotonin,norepinephrine,anddopamine,epinephrineas well as a marked increase in the availability oftrace amines,such astryptamine,octopamine,andphenethylamine.[20][19]The clinical relevance of increased trace amine availability is unclear.

It may also act as anorepinephrine reuptake inhibitorat higher therapeutic doses.[20]Compared toamphetamine,tranylcypromine shows low potency as adopaminereleasing agent,with even weaker potency fornorepinephrineandserotoninrelease.[20][19]

Tranylcypromine has also been shown to inhibit thehistonedemethylase, BHC110/LSD1.Tranylcypromine inhibits this enzyme with an IC50 < 2 μM, thus acting as a small molecule inhibitor of histone demethylation with an effect to derepress the transcriptional activity of BHC110/LSD1 target genes.[27]The clinical relevance of this effect is unknown.

Tranylcypromine has been found to inhibitCYP46A1at nanomolar concentrations.[28]The clinical relevance of this effect is unknown.

Pharmacokinetics

editTranylcypromine reaches its maximum concentration (tmax) within 1–2 hours.[20]After a 20 mg dose, plasma concentrations reach at most 50-200 ng/mL.[20]While itshalf-lifeis only about 2 hours, its pharmacodynamic effects last several days to weeks due to irreversible inhibition of MAO.[20]

Metabolites of tranylcypromine include 4-hydroxytranylcypromine,N-acetyltranylcypromine, andN-acetyl-4-hydroxytranylcypromine, which are less potent MAO inhibitors than tranylcypromine itself.[20]Amphetaminewas once thought to be a metabolite of tranylcypromine, but has not been shown to be.[20][30][19]

Tranylcypromine inhibitsCYP2A6at therapeutic concentrations.[19]

Chemistry

editSynthesis

editHistory

editTranylcypromine was originally developed as ananalogofamphetamine.[4][20]Although it was first synthesized in 1948,[32]its MAOI action was not discovered until 1959. Precisely because tranylcypromine was not, likeisoniazidandiproniazid,ahydrazinederivative, its clinical interest increased enormously, as it was thought it might have a more acceptabletherapeutic indexthan previous MAOIs.[33]

The drug was introduced bySmith, Kline and Frenchin theUnited Kingdomin 1960, and approved in theUnited Statesin 1961.[34]It was withdrawn from the market in February 1964 due to a number of patient deaths involving hypertensive crises with intracranial bleeding. However, it was reintroduced later that year with more limited indications and specific warnings of the risks.[35][20][19]

Research

editTranylcypromine is known to inhibitLSD1,an enzyme that selectivelydemethylatestwolysinesfound onhistone H3.[27][20][36]Genes promoted downstream of LSD1 are involved in cancer cell growth and metastasis, and several tumor cells express high levels of LSD1.[36]Tranylcypromine analogues with more potent and selective LSD1 inhibitory activity are being researched in the potential treatment of cancers.[36][37]

Tranylcypromine may have neuroprotective properties applicable to the treatment ofParkinson's disease,similar to theMAO-Binhibitorsselegilineandrasagiline.[38][11]As of 2017, only one clinical trial in Parkinsonian patients has been conducted, which found some improvement initially and only slight worsening of symptoms after a 1.5 year followup.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ab"International brands for Tranylcypromine".Drugs.com.Retrieved17 April2016.

- ^"FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)".nctr-crs.fda.gov.FDA.Retrieved22 Oct2023.

- ^Anvisa(2023-03-31)."RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial"[Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese).Diário Oficial da União(published 2023-04-04).Archivedfrom the original on 2023-08-03.Retrieved2023-08-16.

- ^abcdefgWilliams DA (2007)."Antidepressants".In Foye WO, Lemke TL, Williams DA (eds.).Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry.Hagerstwon, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 590–1.ISBN978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^"Tranylcypromine".www.drugbank.ca.Retrieved2019-12-06.

- ^Baker GB, Urichuk LJ, McKenna KF, Kennedy SH (June 1999). "Metabolism of monoamine oxidase inhibitors".Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology.19(3): 411–26.doi:10.1023/a:1006901900106.PMID10319194.S2CID21380176.

- ^abBaldessarini RJ (2005). "17. Drug therapy of depression and anxiety disorders". In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL (eds.).Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics.New York: McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0-07-142280-2.

- ^Zametkin A, Rapoport JL, Murphy DL, Linnoila M, Ismond D. Treatment of hyperactive children with monoamine oxidase inhibitors. I. Clinical efficacy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985 Oct;42(10):962-6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790330042005. PMID: 3899047.

- ^Levin GM. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: the pharmacist's role. Am Pharm. 1995 Nov;NS35(11):10-20. PMID: 8533716.

- ^abcde"Tranylcypromine".UK Electronic medicines compendium.Retrieved28 October2015.

- ^abcdeRiederer P, Laux G (March 2011)."MAO-inhibitors in Parkinson's Disease".Experimental Neurobiology.20(1): 1–17.doi:10.5607/en.2011.20.1.1.PMC3213739.PMID22110357.

- ^Jenike MA (September 1981). "Rapid response of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder to tranylcypromine".The American Journal of Psychiatry.138(9): 1249–1250.doi:10.1176/ajp.138.9.1249.PMID7270737.

- ^Marques C, Nardi AE, Mendlowicz M, Figueira I, Andrade Y, Camisão C, et al. (1994)."A tranilcipromina no tratamento do transtorno obsessivoðcompulsivo: relato de seis casos"[The tranylcypromine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Report of six cases].Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria(in Brazilian Portuguese). pp. 400–403.

- ^Joffe RT, Swinson RP (1990)."Tranylcypromine in primary obsessive-compulsive disorder".Journal of Anxiety Disorders.4(4): 365–367.doi:10.1016/0887-6185(90)90033-6.

- ^Nardi AE, Lopes FL, Valença AM, Freire RC, Nascimento I, Veras AB, et al. (February 2010). "Double-blind comparison of 30 and 60 mg tranylcypromine daily in patients with panic disorder comorbid with social anxiety disorder".Psychiatry Research.175(3): 260–265.doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.025.PMID20036427.S2CID45566164.

- ^Saeed SA, Bruce TJ (May 1998)."Panic disorder: effective treatment options".American Family Physician.57(10): 2405–2412.PMID9614411.

- ^abcdefgRicken R, Ulrich S, Schlattmann P, Adli M (August 2017)."Tranylcypromine in mind (Part II): Review of clinical pharmacology and meta-analysis of controlled studies in depression".Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.27(8): 714–731.doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.04.003.PMID28579071.S2CID30987747.

- ^Ulrich S, Ricken R, Buspavanich P, Schlattmann P, Adli M (2020). "Efficacy and Adverse Effects of Tranylcypromine and Tricyclic Antidepressants in the Treatment of Depression: A Systematic Review and Comprehensive Meta-analysis".J Clin Psychopharmacol.40(1): 63–74.doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001153.PMID31834088.S2CID209343653.

- ^abcdefghiGillman PK (February 2011). "Advances pertaining to the pharmacology and interactions of irreversible nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitors".Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology.31(1): 66–74.doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31820469ea.PMID21192146.S2CID10525989.

- ^abcdefghijklmnUlrich S, Ricken R, Adli M (August 2017)."Tranylcypromine in mind (Part I): Review of pharmacology".European Neuropsychopharmacology.27(8): 697–713.doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.05.007.PMID28655495.S2CID4913721.

- ^abKim MJ, Kim KS (2014)."Tyramine production among lactic acid bacteria and other species isolated from kimchi".LWT - Food Science and Technology.56(2): 406–413.doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2013.11.001.

- ^Gillman PK (2016)."Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review concerning dietary tyramine and drug interactions"(PDF).PsychoTropical Commentaries.1:1–90.

- ^van Haelst IM, van Klei WA, Doodeman HJ, Kalkman CJ, Egberts TC (August 2012). "Antidepressive treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and the occurrence of intraoperative hemodynamic events: a retrospective observational cohort study".The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.73(8): 1103–9.doi:10.4088/JCP.11m07607.PMID22938842.

- ^Smith MS, Muir H, Hall R (February 1996). "Perioperative management of drug therapy, clinical considerations".Drugs.51(2): 238–59.doi:10.2165/00003495-199651020-00005.PMID8808166.S2CID46972638.

- ^Blom-Peters L, Lamy M (1993). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors and anesthesia: an updated literature review".Acta Anaesthesiologica Belgica.44(2): 57–60.PMID8237297.

- ^Le Gassicke J, Ashcroft GW, Eccleston D, Evans JI, Oswald I, Ritson EB (1 April 1965). "The Clinical State, Sleep and Amine Metabolism of a Tranylcypromine ('Parnate') Addict".The British Journal of Psychiatry.111(473): 357–364.doi:10.1192/bjp.111.473.357.S2CID145562899.

- ^abLee MG, Wynder C, Schmidt DM, McCafferty DG, Shiekhattar R (June 2006). "Histone H3 lysine 4 demethylation is a target of nonselective antidepressive medications".Chemistry & Biology.13(6): 563–7.doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.004.PMID16793513.

- ^Mast N, Charvet C, Pikuleva IA, Stout CD (October 2010)."Structural basis of drug binding to CYP46A1, an enzyme that controls cholesterol turnover in the brain".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.285(41): 31783–95.doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.143313.PMC2951250.PMID20667828.

- ^Gaweska H, Fitzpatrick PF (October 2011)."Structures and Mechanism of the Monoamine Oxidase Family".Biomolecular Concepts.2(5): 365–377.doi:10.1515/BMC.2011.030.PMC3197729.PMID22022344.

- ^Sherry RL, Rauw G, McKenna KF, Paetsch PR, Coutts RT, Baker GB (December 2000). "Failure to detect amphetamine or 1-amino-3-phenylpropane in humans or rats receiving the MAO inhibitor tranylcypromine".Journal of Affective Disorders.61(1–2): 23–9.doi:10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00188-3.PMID11099737.

- ^A US patent 4016204 A,Rajadhyaksha VJ, "Method of synthesis of trans-2-phenylcyclopropylamine", published 1977-04-05, assigned to Nelson Research & Development Company

- ^Burger A, Yost WL (1948). "Arylcycloalkylamines. I. 2-Phenylcyclopropylamine".Journal of the American Chemical Society.70(6): 2198–2201.doi:10.1021/ja01186a062.

- ^López-Muñoz F, Alamo C (2009). "Monoaminergic neurotransmission: the history of the discovery of antidepressants from 1950s until today".Current Pharmaceutical Design.15(14): 1563–86.doi:10.2174/138161209788168001.PMID19442174.

- ^Shorter E (2009).Before Prozac: the troubled history of mood disorders in psychiatry.Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-536874-1.

- ^Atchley DW (September 1964). "Reevaluation of Tranylcypromine Sulfate(Parnate Sulfate)".JAMA.189(10): 763–4.doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03070100057011.PMID14174054.

- ^abcZheng YC, Yu B, Jiang GZ, Feng XJ, He PX, Chu XY, et al. (2016). "Irreversible LSD1 Inhibitors: Application of Tranylcypromine and Its Derivatives in Cancer Treatment".Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry.16(19): 2179–88.doi:10.2174/1568026616666160216154042.PMID26881714.

- ^Przespolewski A, Wang ES (July 2016). "Inhibitors of LSD1 as a potential therapy for acute myeloid leukemia".Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs.25(7): 771–80.doi:10.1080/13543784.2016.1175432.PMID27077938.S2CID20858344.

- ^Al-Nuaimi SK, Mackenzie EM, Baker GB (November 2012). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors and neuroprotection: a review".American Journal of Therapeutics.19(6): 436–48.doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e31825b9eb5.PMID22960850.