TheTreaty of Livadiawas anunequal treatybetween theRussian Empireand the ChineseQing dynastysigned inLivadiya, Crimea,on 2 October 1879,[1]wherein Russia agreed to return a portion of the lands it had occupied inXinjiangduring theDungan Revolt of 1862–1877.Even though Qing forces obtained the area. As a result of its disapproval, the Chinese government refused to ratify it and the emissary who made the negotiations was sentenced to death (although the sentence was not carried out). Seventeen months later, the two nations signed theTreaty of Saint Petersburg,which apart from territorial matters, largely had the same terms as the Treaty of Livadia.

| |

| Drafted | 2 October 1879 |

|---|---|

| Location | Livadiya, Crimea,Russian Empire |

| Condition | Unratified; superseded by theTreaty of Saint Petersburg (1881) |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Treaty of Livadia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Lí ngõa kỉ á điều ước | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Lí ngõa kỉ á điều ước | ||||||

| |||||||

| Russian name | |||||||

| Russian | Ливадийский договор | ||||||

| Romanization | Livadiyskiy dogovor | ||||||

Background

editTheQing dynastyunder theQianlong Emperorconquered Xinjiang from theDzungar Khanatein the late 1750s. However, Qing China declined in the late 19th century following theFirst Opium War.A major revolt known as theDungan Revoltoccurred in the 1860s and 1870s inNorthwest China,andQing rulealmost collapsed in all of Xinjiang except for places such asTacheng.Taking advantage of this revolt,Yakub Beg,commander-in-chief of the army ofKokand,occupied most of Xinjiang and declared himself theEmirofKashgaria.[2]

Russia was officially neutral during the conflict, but as a result of theTreaty of Tarbagataiin 1864, had already gained about 350,000 square miles (910,000 km2) of territory in Xinjiang.[3]Furthermore, the Russian Governor-General ofTurkestanhad sent troops into theIli Valleyin 1871, ostensibly to protect his citizens during the rebellion, but they had extensively built up infrastructure in the Ili capital ofGhulja.[4]This was typical of the Russian strategy of taking control over a region and negotiating recognition of its sovereignty after the fact.[5]

TheQing counterinsurgency,led by GeneralZuo Zongtangbegan in September 1876 and concluded in December 1877, having completely retaken the lands that were lost.[6]During this time, Russia had promised to return all occupied lands to China.[7]

Terms of the treaty

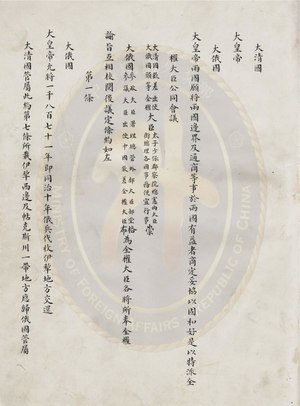

editThe Treaty of Livadia actually consisted of two separate agreements.

Border treaty

editThe first treaty consisted of eighteen articles, and stipulated that:[8]

- Russia would return a portion of Xinjiang to China, keeping the western Ili Valley and the Tekes River – ensuring that Russia would have access to the southern portion of Xinjiang

- In the lands that were being returned, Russia would retain any property rights it had established during the occupation

- Any of theDungan peoplewho rebelled could choose to become Russian citizens, and those who did not would not be punished for their activities during the rebellion

- Russia was given the right to open seven new consulates in Xinjiang and Mongolia

- Russia could engage in trade withoutdutiesin Xinjiang and Mongolia

- Russian merchants were given access to trade routes extending as far asBeijingandHankouon theYangtze

- China would pay anindemnityof five millionrublesto cover Russia's occupation costs and property losses

Commercial treaty

editThe second treaty contained seventeen articles that focused on thelogisticsof conducting trade, such as tax issues, passport requirements, and certification procedures, the total effect of which was very preferential to Russian commercial interests and represented unprecedented access to the Chinese interior. There was also an unrelated supplementary article that reaffirmed Russia's right to navigate theSonghua Riveras far asTongjianginManchuria.[9]

Uproar in China

editAt the time of negotiations, China was in a strong position. Zuo's army was still in the region and far outnumbered the Russian troops that remained. Furthermore, Russia had recently concluded theRusso-Turkish Warand the resultingTreaty of Berlinhad not been particularly favorable to them. Military expenditures during that war had also drained the national treasury, so the fact that the terms of Livadia were so heavily in their favor came as quite a shock among government officials when they became widely known.[10]

The Qing court laid the blame on the chief negotiator,Chonghou,who was described as being inexperienced and over-eager to return home.[10]Upon his return to Beijing in January 1880, he was denounced as a traitor, stripped of his rank and office, and imprisoned. The government decided it needed tosave faceand following the Chinese proverb "kill the chicken to scare the monkey",ordered his execution.[11][12]Zhang Zhidongstated that "The Russians must be considered extremely covetous and truculent in making the demands and Chonghou was extremely stupid and absurd in accepting them... If we insist on changing the treaty, there may not be trouble; if we do not, we are unworthy to be called a state."[13]Additionally, the government declared it would refuse toratifythe treaty and pressed Russia to reopen negotiations. Naturally, Russia wanted to keep the treaty terms, but their only options were to risk another war in Xinjiang, which they were ill-prepared to fight, or agree to China's request. Russia understood that theGreat Powerswould not ignore an attempt to enforce an unratified treaty and had even kept the conditions a secret, fearing that European powers would intervene on China's behalf if the terms became known. Given their financial situation and the fact that Ili was not crucial to Russian security, they agreed to discuss a new treaty, but on one condition: that Chonghou waspardonedand his life was spared.[14][12]

As the months passed, tensions between the two countries remained high and both sides prepared for war. China dispatchedZeng Jizeas their new negotiator. The foreign emissaries in Beijing pleaded on behalf of Chonghou, and evenQueen Victoriapersonally interceded. Finally, on 12 August 1880, it was announced that Chonghou would be freed, and negotiations resumed. The resultingTreaty of Saint Petersburgkept many of the same provisions as the Treaty of Livadia, with the major exceptions being that Russia would return almost all of Xinjiang, less a small area reserved for Dungans who wanted to become Russian citizens, and that the amount of the indemnity payment increased.[12][15]

Analysis

editFor many years, the story that Chonghou was solely responsible for the debacle was perpetuated by the Chinese government, and this was the view put forth by historians as well. Although Chonghou had survived, he was turned into a nonperson by the government; he was expunged from government records and his letters were not published posthumously, as was the custom for Chinese court officials. Furthermore, neither the Chinese nor Russian governments retained any documents from the negotiations, thus making it difficult to determine how China ended up with anunequal treatydespite being in the better negotiating position.[16]

HistorianS. C. M. Paineinvestigated the circumstances around the treaty and discovered that contrary to the official story, Chonghou was an experienced diplomat and had a career of over thirty years in negotiations with France, Britain, and the United States.[10]In fact, he led the delegation to France to offer the Chinese apology after theTianjin Massacrein 1870.[17]

Instead, Paine believes blame should be laid on the Qing government as a whole. At theZongli Yamen(Ministry of Foreign Affairs),Prince Gong,who had founded the ministry, had plenty of experience dealing with Russia during negotiations for theConvention of Pekingin 1860, and during the Russian occupation period, there was plenty of communication between the two countries that Russian territorial and commercial demands should have been known long before negotiations started. However, despite its charter, the Zongli Yamen was not the only agency that dealt with foreign affairs. Even within the ministry, there was a split between those who were open to foreigners (such as Prince Gong) and those who were not.[18]

Paine argues that given Chonghou's experience, because the terms were so unfavourable to China, it is unlikely that he would have made those concessions on his own, as evidenced from the subsequent outrage. It was only whenEmpress Dowager Cixisought comment on the treaty from others that it turned into a scandal.[19]Cixi's installation ofher nephewas emperor also created a power struggle in the government between her and Prince Gong, whose son was also in contention to succeed theTongzhi Emperor.Thus, Prince Gong might have been distracted and unable to apply his foreign affairs expertise. In addition,Wenxiang,another diplomat who was also experienced in negotiating with Westerners, had died in 1876.[20]

In short, Paine believes that Chonghou was poorly advised by the Zongli Yamen and when the court became outraged by the treaty, he became the scapegoat, otherwise the ministry and by extensionManchus(who made up the majority of Zongli Yamen officials) would have to take the blame.[11]

References

editCitations

edit- ^"Lessons of History".A Century of Resilient Tradition: Exhibition of the Republic of China's Diplomatic Archives.National Palace Museum.9 August 2011.Retrieved23 February2018.

- ^Fields, Lanny B. (1978).Tso Tsung-tʼang and the Muslims: statecraft in northwest China, 1868-1880.Limestone Press. p. 81.ISBN0-919642-85-3.Retrieved28 June2010.

- ^Paine 1996,p. 29.

- ^Millward 2007,p. 133.

- ^Chen, Wei-hsing (2009)."The Negotiations on Ili Contract between China and Russia in the Last Half 19th Century: A Case Study of Treaties and Border Maps in Nation Palace Museum"(Microsoft Word).Research Quarterly.27(1). Taipei, Taiwan:National Palace Museum.

- ^Kim, Ho-dong (2004).Holy war in China: the Muslim rebellion and state in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877.Stanford University Press. p. 176.ISBN0-8047-4884-5.Retrieved28 June2010.

- ^Millward 2007,pp. 133–134.

- ^Paine 1996,p. 133–134.

- ^Paine 1996,p. 134.

- ^abcMillward 2007,p. 134.

- ^abPaine 1996,p. 140.

- ^abcAnonymous (1894).Russia's March Towards India.S. Low, Marston & Company. pp. 270–272.Retrieved22 February2018.

- ^Fairbank, John King; Liu, Kwang-Ching; Twitchett, Denis Crispin, eds. (1980).Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911.Vol. 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 94.ISBN0-521-22029-7.Retrieved18 January2012.

- ^Paine 1996,pp. 140–141.

- ^Giles, Herbert Allen (1898).A Chinese Biographical Dictionary.Bernard Quaritch. p. 210.Retrieved22 February2018.

- ^Paine 1996,p. 132.

- ^Tu, Lien-Chê (1943)..InHummel, Arthur W. Sr.(ed.).Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period.United States Government Printing Office.

- ^Paine 1996,p. 138.

- ^Paine 1996,pp. 136–137.

- ^Paine 1996,p. 139.

Sources

edit- Millward, James A. (2007).Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang.Columbia University Press. pp. 133–135.ISBN9780231139243.Retrieved22 February2018.

- Paine, S. C. M. (1996)."Chinese Diplomacy in Disarray: The Treaty of Livadia".Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier.M.E. Sharpe. pp. 133–145.ISBN9781563247248.Retrieved22 February2018.