Carcinogenesis,also calledoncogenesisortumorigenesis,is the formation of acancer,whereby normalcellsaretransformedintocancer cells.The process is characterized by changes at the cellular,genetic,andepigeneticlevels and abnormalcell division.Cell division is a physiological process that occurs in almost alltissuesand under a variety of circumstances. Normally, the balance between proliferation and programmed cell death, in the form ofapoptosis,is maintained to ensure the integrity of tissues andorgans.According to the prevailing accepted theory of carcinogenesis, the somatic mutation theory,mutationsinDNAandepimutationsthat lead to cancer disrupt these orderly processes by interfering with the programming regulating the processes, upsetting the normal balance between proliferation and cell death.[1][2][3][4][5]This results in uncontrolled cell division and theevolution of those cellsbynatural selectionin the body. Only certain mutations lead to cancer whereas the majority of mutations do not.[citation needed]

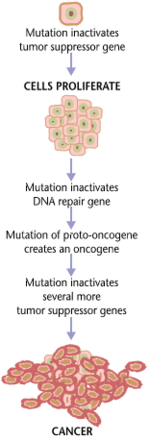

Variants of inherited genes may predispose individuals to cancer. In addition, environmental factors such ascarcinogensand radiation cause mutations that may contribute to the development of cancer. Finally random mistakes in normal DNA replication may result in cancer-causing mutations.[6]A series of several mutations to certain classes of genes is usually required before a normal cell will transform into acancer cell.[7][8][9][10][11]Recent comprehensive patient-level classification and quantification of driver events inTCGAcohorts revealed that there are on average 12 driver events per tumor, of which 0.6 arepoint mutationsinoncogenes,1.5 areamplificationsof oncogenes, 1.2 are point mutations intumor suppressors,2.1 aredeletionsof tumor suppressors, 1.5 are driverchromosome losses,1 is a driverchromosome gain,2 are driverchromosome arm losses,and 1.5 are driverchromosome arm gains.[12]Mutations in genes that regulate cell division,apoptosis(cell death), andDNA repairmay result in uncontrolled cell proliferation and cancer.

Canceris fundamentally a disease of regulation of tissue growth. In order for a normal cell totransforminto a cancer cell,genesthat regulate cell growth and differentiation must be altered.[13]Genetic and epigenetic changes can occur at many levels, from gain or loss of entire chromosomes, to a mutation affecting asingle DNA nucleotide,or to silencing or activating a microRNA that controls expression of 100 to 500 genes.[14][15]There are two broad categories of genes that are affected by these changes.Oncogenesmay be normal genes that are expressed at inappropriately high levels, or altered genes that have novel properties. In either case, expression of these genes promotes the malignant phenotype of cancer cells.Tumor suppressor genesare genes that inhibit cell division, survival, or other properties of cancer cells. Tumor suppressor genes are often disabled by cancer-promoting genetic changes. FinallyOncovirinae,virusesthat contain anoncogene,are categorized as oncogenic because they trigger the growth of tumorous tissues in thehost.This process is also referred to asviral transformation.It is also believed that cancer is caused due to chromosomal abnormalities as explained inchromosome theory of cancer.[16]

Causes

editGenetic and epigenetic

editThere is a diverse classification scheme for the various genomic changes that may contribute to the generation ofcancer cells.Many of these changes aremutations,or changes in thenucleotidesequence of genomic DNA. There are also many epigenetic changes that alter whether genes are expressed or not expressed.Aneuploidy,the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes, is one genomic change that is not a mutation, and may involve either gain or loss of one or morechromosomesthrough errors inmitosis.Large-scale mutations involve either thedeletionorduplicationof a portion of a chromosome.Genomic amplificationoccurs when a cell gains many copies (often 20 or more) of a small chromosomal region, usually containing one or more oncogenes and adjacent genetic material.Translocationoccurs when two separate chromosomal regions become abnormally fused, often at a characteristic location. A well-known example of this is thePhiladelphia chromosome,or translocation of chromosomes 9 and 22, which occurs inchronic myelogenous leukemia,and results in production of theBCR-ablfusion protein,an oncogenictyrosine kinase.Small-scale mutations includepoint mutations,deletions,andinsertions,which may occur in thepromoterof a gene and affect itsexpression,or may occur in the gene'scoding sequenceand alter the function or stability of itsproteinproduct. Disruption of a single gene may also result fromintegration of genomic materialfrom aDNA virusorretrovirus,and such an event may also result in the expression of viral oncogenes in the affected cell and its descendants.[citation needed]

DNA damage

editDNA damage is considered to be the primary cause of cancer.[17]More than 60,000 new naturally-occurring instances of DNA damage arise, on average, per human cell, per day, due to endogenous cellular processes (see articleDNA damage (naturally occurring)).

Additional DNA damage can arise from exposure toexogenousagents. As one example of anexogenouscarcinogenic agent, tobacco smoke causes increased DNA damage, and this DNA damage likely cause the increase of lung cancer due to smoking.[18]In other examples, UV light from solar radiation causes DNA damage that is important inmelanoma,[19]Helicobacter pyloriinfection produces high levels ofreactive oxygen speciesthat damage DNA and contribute togastric cancer,[20]and theAspergillus flavusmetaboliteaflatoxinis a DNA damaging agent that is causative in liver cancer.[21]

DNA damage can also be caused bysubstances produced in the body.Macrophages and neutrophils in an inflamed colonic epithelium are the source of reactive oxygen species causing the DNA damage that initiates colonictumorigenesis,[22]and bile acids, at high levels in the colons of humans eating a high-fat diet, also cause DNA damage and contribute to colon cancer.[23]

Such exogenous and endogenous sources of DNA damage are indicated in the boxes at the top of the figure in this section. The central role of DNA damage in progression to cancer is indicated at the second level of the figure. The central elements of DNA damage,epigeneticalterations and deficient DNA repair in progression to cancer are shown in red.

A deficiency in DNA repair would cause more DNA damage to accumulate, and increase the risk for cancer. For example, individuals with an inherited impairment in any of 34DNA repair genes(see articleDNA repair-deficiency disorder) are at increased risk of cancer, with some defects causing an up to 100% lifetime chance of cancer (e.g.p53mutations).[24]Suchgermline mutationsare shown in a box at the left of the figure, with an indication of their contribution to DNA repair deficiency. However, such germline mutations (which cause highlypenetrantcancer syndromes) are the cause of only aboutone percentof cancers.[25]

The majority of cancers are called non-hereditary or "sporadic cancers". About 30% of sporadic cancers do have some hereditary component that is currently undefined, while the majority, or 70% of sporadic cancers, have no hereditary component.[26]

In sporadic cancers, a deficiency in DNA repair is occasionally due to a mutation in a DNA repair gene; much more frequently, reduced or absent expression of DNA repair genes is due toepigenetic alterationsthat reduce orsilence gene expression.This is indicated in the figure at the 3rd level from the top. For example, for 113 colorectal cancers examined in sequence, only four had amissense mutationin the DNA repair geneMGMT,while the majority had reduced MGMT expression due tomethylationof the MGMTpromoter region(an epigenetic alteration).[27]

When expression of DNA repair genes is reduced, this causes a DNA repair deficiency. This is shown in the figure at the 4th level from the top. With a DNA repair deficiency, DNA damage persists in cells at a higher than typical level (5th level from the top in figure); this excess damage causes an increased frequency of mutation and/orepimutation(6th level from top of figure). Experimentally, mutation rates increase substantially in cells defective inDNA mismatch repair[28][29]or inHomologous recombinationalrepair (HRR).[30]Chromosomal rearrangementsandaneuploidyalso increase in HRR-defective cells[31]During repair of DNA double-strand breaks, or repair of other DNA damage, incompletely-cleared repair sites can cause epigenetic gene silencing.[32][33]

The somatic mutations and epigenetic alterations caused by DNA damage and deficiencies in DNA repair accumulate infield defects.Field defects are normal-appearing tissues with multiple alterations (discussed in the section below), and are common precursors to development of the disordered and over-proliferating clone of tissue in a cancer. Such field defects (second level from bottom of figure) may have numerous mutations and epigenetic alterations.

It is impossible to determine the initial cause for most specific cancers. In a few cases, only one cause exists: for example, the virusHHV-8causes allKaposi's sarcomas.However, with the help ofcancer epidemiologytechniques and information, it is possible to produce an estimate of a likely cause in many more situations. For example,lung cancerhas several causes, including tobacco use andradon gas.Men who currently smoke tobacco develop lung cancer at a rate 14 times that of men who have never smoked tobacco: the chance of lung cancer in a current smoker being caused by smoking is about 93%; there is a 7% chance that the smoker's lung cancer was caused by radon gas or some other, non-tobacco cause.[34]These statistical correlations have made it possible for researchers to infer that certain substances or behaviors are carcinogenic. Tobacco smoke causes increasedexogenousDNA damage, and this DNA damage is the likely cause of lung cancer due to smoking. Among the more than 5,000 compounds in tobacco smoke, thegenotoxicDNA-damaging agents that occur both at the highest concentrations, and which have the strongest mutagenic effects areacrolein,formaldehyde,acrylonitrile,1,3-butadiene,acetaldehyde,ethylene oxideandisoprene.[18]

Usingmolecular biologicaltechniques, it is possible to characterize the mutations, epimutations or chromosomal aberrations within a tumor, and rapid progress is being made in the field of predicting certain cancer patients'prognosisbased on the spectrum of mutations. For example, up to half of all tumors have a defective p53 gene. This mutation is associated with poor prognosis, since those tumor cells are less likely to go intoapoptosisorprogrammed cell deathwhen damaged by therapy.Telomerasemutations remove additional barriers, extending the number of times a cell can divide. Other mutations enable the tumor togrow new blood vesselsto provide more nutrients, or tometastasize,spreading to other parts of the body. However, once a cancer is formed it continues to evolve and to produce sub-clones. It was reported in 2012 that a single renal cancer specimen, sampled in nine different areas, had 40 "ubiquitous" mutations, found in all nine areas, 59 mutations shared by some, but not all nine areas, and 29 "private" mutations only present in one area.[35]

The lineages of cells in which all these DNA alterations accumulate are difficult to trace, but two recent lines of evidence suggest that normalstem cellsmay be the cells of origin in cancers.[36][37]First, there exists a highly positive correlation (Spearman's rho = 0.81; P < 3.5 × 10−8) between the risk of developing cancer in a tissue and the number of normal stem cell divisions taking place in that same tissue. The correlation applied to 31 cancer types and extended across fiveorders of magnitude.[38]This correlation means that if normal stem cells from a tissue divide once, the cancer risk in that tissue is approximately 1X. If they divide 1,000 times, the cancer risk is 1,000X. And if the normal stem cells from a tissue divide 100,000 times, the cancer risk in that tissue is approximately 100,000X. This strongly suggests that the main factor in cancer initiation is the fact that "normal" stem cells divide, which implies that cancer originates in normal, healthy stem cells.[37]

Second, statistics show that most human cancers are diagnosed in older people. A possible explanation is that cancers occur because cells accumulate damage through time. DNA is the only cellular component that can accumulate damage over the entire course of a life, and stem cells are the only cells that can transmit DNA from the zygote to cells late in life. Other cells, derived from stem cells, do not keep DNA from the beginning of life until a possible cancer occurs. This implies that most cancers arise from normal stem cells.[36][37]

Contribution of field defects

editThe term "field cancerization"was first used in 1953 to describe an area or" field "of epithelium that has been preconditioned by (at that time) largely unknown processes so as to predispose it towards development of cancer.[39]Since then, the terms "field cancerization" and "field defect" have been used to describe pre-malignant tissue in which new cancers are likely to arise.[citation needed]

Field defects have been identified in association with cancers and are important in progression to cancer.[40][41]However, it was pointed out by Rubin[42]that "the vast majority of studies in cancer research has been done on well-defined tumors in vivo, or on discrete neoplastic foci in vitro. Yet there is evidence that more than 80% of the somatic mutations found inmutator phenotypehuman colorectal tumors occur before the onset of terminal clonal expansion… "[43]More than half of somatic mutations identified in tumors occurred in a pre-neoplastic phase (in a field defect), during growth of apparently normal cells. It would also be expected that many of the epigenetic alterations present in tumors may have occurred in pre-neoplastic field defects.[44]

In the colon, a field defect probably arises by natural selection of a mutant or epigenetically altered cell among the stem cells at the base of one of theintestinal cryptson the inside surface of the colon. A mutant or epigenetically altered stem cell may replace the other nearby stem cells by natural selection. This may cause a patch of abnormal tissue to arise. The figure in this section includes a photo of a freshlyresectedand lengthwise-opened segment of the colon showing a colon cancer and four polyps. Below the photo there is a schematic diagram of how a large patch of mutant or epigenetically altered cells may have formed, shown by the large area in yellow in the diagram. Within this first large patch in the diagram (a large clone of cells), a second such mutation or epigenetic alteration may occur, so that a given stem cell acquires an advantage compared to its neighbors, and this altered stem cell may expand clonally, forming a secondary patch, or sub-clone, within the original patch. This is indicated in the diagram by four smaller patches of different colors within the large yellow original area. Within these new patches (sub-clones), the process may be repeated multiple times, indicated by the still smaller patches within the four secondary patches (with still different colors in the diagram) which clonally expand, until stem cells arise that generate either small polyps or else a malignant neoplasm (cancer). In the photo, an apparent field defect in this segment of a colon has generated four polyps (labeled with the size of the polyps, 6mm, 5mm, and two of 3mm, and a cancer about 3 cm across in its longest dimension). These neoplasms are also indicated (in the diagram below the photo) by 4 small tan circles (polyps) and a larger red area (cancer). The cancer in the photo occurred in the cecal area of the colon, where the colon joins the small intestine (labeled) and where the appendix occurs (labeled). The fat in the photo is external to the outer wall of the colon. In the segment of colon shown here, the colon was cut open lengthwise to expose its inner surface and to display the cancer and polyps occurring within the inner epithelial lining of the colon.[citation needed]

If the general process by which sporadic colon cancers arise is the formation of a pre-neoplastic clone that spreads by natural selection, followed by formation of internal sub-clones within the initial clone, and sub-sub-clones inside those, then colon cancers generally should be associated with, and be preceded by, fields of increasing abnormality, reflecting the succession of premalignant events. The most extensive region of abnormality (the outermost yellow irregular area in the diagram) would reflect the earliest event in formation of a malignant neoplasm.

In experimental evaluation of specific DNA repair deficiencies in cancers, many specific DNA repair deficiencies were also shown to occur in the field defects surrounding those cancers. The table below gives examples for which the DNA repair deficiency in a cancer was shown to be caused by an epigenetic alteration, and the somewhat lower frequencies with which the same epigenetically caused DNA repair deficiency was found in the surrounding field defect.

| Cancer | Gene | Frequency in Cancer | Frequency in Field Defect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal | MGMT | 46% | 34% | [45] |

| Colorectal | MGMT | 47% | 11% | [46] |

| Colorectal | MGMT | 70% | 60% | [47] |

| Colorectal | MSH2 | 13% | 5% | [46] |

| Colorectal | ERCC1 | 100% | 40% | [48] |

| Colorectal | PMS2 | 88% | 50% | [48] |

| Colorectal | XPF | 55% | 40% | [48] |

| Head and Neck | MGMT | 54% | 38% | [49] |

| Head and Neck | MLH1 | 33% | 25% | [50] |

| Head and Neck | MLH1 | 31% | 20% | [51] |

| Stomach | MGMT | 88% | 78% | [52] |

| Stomach | MLH1 | 73% | 20% | [53] |

| Esophagus | MLH1 | 77%–100% | 23%–79% | [54] |

Some of the small polyps in the field defect shown in the photo of the opened colon segment may be relatively benign neoplasms. In a 1996 study of polyps less than 10mm in size found during colonoscopy and followed with repeat colonoscopies for 3 years, 25% remained unchanged in size, 35% regressed or shrank in size and 40% grew in size.[55]

Genome instability

editCancers are known to exhibitgenome instabilityor a "mutator phenotype".[56]The protein-coding DNA within the nucleus is about 1.5% of the total genomic DNA.[57]Within this protein-coding DNA (called theexome), an average cancer of the breast or colon can have about 60 to 70 protein altering mutations, of which about 3 or 4 may be "driver" mutations, and the remaining ones may be "passenger" mutations.[44]However, the average number of DNA sequence mutations in the entire genome (includingnon-protein-coding regions) within a breast cancer tissue sample is about 20,000.[58]In an average melanoma tissue sample (melanomas have a higherexomemutation frequency),[44]) the total number of DNA sequence mutations is about 80,000.[59]These high frequencies of mutations in the total nucleotide sequences within cancers suggest that often an early alteration in the field defect giving rise to a cancer (e.g. yellow area in the diagram in the preceding section) is a deficiency in DNA repair. Large field defects surrounding colon cancers (extending to about 10 cm on each side of a cancer) are found[48]to frequently have epigenetic defects in two or three DNA repair proteins (ERCC1,ERCC4(XPF) and/orPMS2) in the entire area of the field defect. When expression of DNA repair genes is reduced, DNA damage accumulates in cells at a higher than normal rate, and this excess damage causes an increased frequency of mutation and/or epimutation. Mutation rates strongly increase in cells defective inDNA mismatch repair[28][29]or inhomologous recombinationalrepair (HRR).[30]A deficiency in DNA repair, itself, can allow DNA damage to accumulate, and error-pronetranslesion synthesisof some of the damaged areas may give rise to mutations. In addition, faulty repair of this accumulated DNA damage may give rise to epimutations. These new mutations and/or epimutations may provide a proliferative advantage, generating a field defect. Although the mutations/epimutations in DNA repair genes do not, themselves, confer a selective advantage, they may be carried along as passengers in cells when the cell acquires an additional mutation/epimutation that does provide a proliferative advantage.[citation needed]

Non-mainstream theories

editThere are a number of theories of carcinogenesis and cancer treatment that fall outside the mainstream of scientific opinion, due to lack of scientific rationale, logic, or evidence base. These theories may be used to justify various alternative cancer treatments. They should be distinguished from those theories of carcinogenesis that have a logical basis within mainstream cancer biology, and from which conventionally testable hypotheses can be made.[citation needed]

Several alternative theories of carcinogenesis, however, are based on scientific evidence and are increasingly being acknowledged. Some researchers believe that cancer may be caused byaneuploidy(numerical and structural abnormalities in chromosomes)[60]rather than by mutations or epimutations. Cancer has also been considered as a metabolic disease, in which the cellular metabolism of oxygen is diverted from the pathway that generates energy (oxidative phosphorylation) to the pathway that generatesreactive oxygen species.[61]This causes an energy switch from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect), and the accumulation ofreactive oxygen speciesleading tooxidative stress( "oxidative stress theory of cancer" ).[61]Another concept of cancer development is based on exposure to weakmagneticandelectromagnetic fieldsand their effects onoxidative stress,known as magnetocarcinogenesis.[62]

A number of authors have questioned the assumption that cancers result from sequential random mutations as oversimplistic, suggesting instead that cancer results from a failure of the body to inhibit an innate, programmed proliferative tendency.[63]A related theory suggests that cancer is anatavism,an evolutionary throwback to an earlier form ofmulticellular life.[64]The genes responsible for uncontrolled cell growth and cooperation betweencancer cellsare very similar to those that enabled the first multicellular life forms to group together and flourish. These genes still exist within the genomes of more complexmetazoans,such as humans, although more recently evolved genes keep them in check. When the newer controlling genes fail for whatever reason, the cell can revert to its more primitive programming and reproduce out of control. The theory is an alternative to the notion that cancers begin with rogue cells that undergo evolution within the body. Instead, they possess a fixed number of primitive genes that are progressively activated, giving them finite variability.[65]Another evolutionary theory puts the roots of cancer back to the origin of theeukaryote(nucleated) cell by massivehorizontal gene transfer,when the genomes of infecting viruses were cleaved (and thereby attenuated) by the host, but their fragments integrated into the host genome as immune protection. Cancer thus originates when a rare somatic mutation recombines such fragments into a functional driver of cell proliferation.[66]

Cancer cell biology

editOften, the multiple genetic changes that result in cancer may take many years to accumulate. During this time, the biological behavior of the pre-malignant cells slowly changes from the properties of normal cells to cancer-like properties. Pre-malignant tissue can have adistinctive appearance under the microscope.Among the distinguishing traits of a pre-malignant lesion are an increasednumber of dividing cells,variation innuclearsize and shape, variation in cellsizeandshape,loss ofspecialized cell features,and loss of normal tissue organization.Dysplasiais an abnormal type of excessive cell proliferation characterized by loss of normal tissue arrangement and cell structure in pre-malignant cells. These earlyneoplasticchanges must be distinguished fromhyperplasia,a reversible increase in cell division caused by an external stimulus, such as a hormonal imbalance or chronic irritation.[citation needed]

The most severe cases of dysplasia are referred to ascarcinoma in situ.In Latin, the termin situmeans "in place";carcinoma in siturefers to an uncontrolled growth of dysplastic cells that remains in its original location and has not showninvasioninto other tissues. Carcinoma in situ may develop into an invasive malignancy and is usually removed surgically when detected.

Clonal evolution

editJust as a population of animals undergoesevolution,an unchecked population of cells also can undergo "evolution". This undesirable process is calledsomatic evolution,and is how cancer arises and becomes more malignant over time.[67]

Most changes in cellular metabolism that allow cells to grow in a disorderly fashion lead to cell death. However, once cancer begins,cancer cellsundergo a process ofnatural selection:the few cells with new genetic changes that enhance their survival or reproduction multiply faster, and soon come to dominate the growing tumor as cells with less favorable genetic change are out-competed.[68]This is the same mechanism by whichpathogenicspecies such asMRSAcan becomeantibiotic-resistantand by whichHIVcan becomedrug-resistant,and by which plant diseases and insects can becomepesticide-resistant.This evolution explains why a cancerrelapseoften involves cells that have acquiredcancer-drug resistanceor resistance toradiotherapy.

Biological properties of cancer cells

editIn a 2000 article byHanahanandWeinberg,the biological properties of malignant tumor cells were summarized as follows:[69]

- Acquisition of self-sufficiency ingrowth signals,leading to unchecked growth.

- Loss of sensitivity to anti-growth signals, also leading to unchecked growth.

- Loss of capacity forapoptosis,allowing growth despite genetic errors and external anti-growth signals.

- Loss of capacity forsenescence,leading to limitless replicative potential (immortality)

- Acquisition ofsustained angiogenesis,allowing the tumor to grow beyond the limitations of passive nutrient diffusion.

- Acquisition of ability to invade neighbouringtissues,the defining property of invasive carcinoma.

- Acquisition of ability to seedmetastasesat distant sites, a late-appearing property of some malignant tumors (carcinomas or others).

The completion of these multiple steps would be a very rare event without:

- Loss of capacity to repair genetic errors, leading to an increasedmutationrate (genomic instability), thus accelerating all the other changes.

These biological changes are classical incarcinomas;other malignant tumors may not need to achieve them all. For example, given that tissue invasion and displacement to distant sites are normal properties ofleukocytes,these steps are not needed in the development ofleukemia.Nor do the different steps necessarily represent individual mutations. For example, inactivation of a single gene, coding for thep53protein, will cause genomic instability, evasion of apoptosis and increased angiogenesis. Further, not all thecancer cellsare dividing. Rather, a subset of the cells in a tumor, calledcancer stem cells,replicate themselves as they generate differentiated cells.[70]

Cancer as a defect in cell interactions

editNormally, once a tissue is injured or infected, damaged cells elicit inflammation by stimulating specific patterns of enzyme activity and cytokine gene expression in surrounding cells.[71][72]Discrete clusters ( "cytokine clusters" ) of molecules are secreted, which act as mediators, inducing the activity of subsequent cascades of biochemical changes.[73]Each cytokine binds to specific receptors on various cell types, and each cell type responds in turn by altering the activity of intracellular signal transduction pathways, depending on the receptors that the cell expresses and the signaling molecules present inside the cell.[74][75]Collectively, this reprogramming process induces a stepwise change in cell phenotypes, which will ultimately lead to restoration of tissue function and toward regaining essential structural integrity.[76][77]A tissue can thereby heal, depending on the productive communication between the cells present at the site of damage and the immune system.[78]One key factor in healing is the regulation of cytokine gene expression, which enables complementary groups of cells to respond to inflammatory mediators in a manner that gradually produces essential changes in tissue physiology.[79][80][81]Cancer cells have either permanent (genetic) or reversible (epigenetic) changes to their genome, which partly inhibit their communication with surrounding cells and with the immune system.[82][83]Cancer cells do not communicate with their tissue microenvironment in a manner that protects tissue integrity; instead, the movement and the survival of cancer cells become possible in locations where they can impair tissue function.[84][85]Cancer cells survive by "rewiring" signal pathways that normally protect the tissue from the immune system. This alteration of the immune response is evident in early stages of malignancy too.[86][87]

One example of tissue function rewiring in cancer is the activity of transcription factorNF-κB.[88] NF-κB activates the expression of numerous genes involved in the transition between inflammation and regeneration, which encode cytokines, adhesion factors, and other molecules that can change cell fate.[89]This reprogramming of cellular phenotypes normally allows the development of a fully functional intact tissue.[90]NF-κB activity is tightly controlled by multiple proteins, which collectively ensure that only discrete clusters of genes are induced by NF-κB in a given cell and at a given time.[91]This tight regulation of signal exchange between cells protects the tissue from excessive inflammation, and ensures that different cell types gradually acquire complementary functions and specific positions. Failure of this mutual regulation between genetic reprogramming and cell interactions allows cancer cells to give rise to metastasis. Cancer cells respond aberrantly to cytokines, and activate signal cascades that can protect them from the immune system.[88][92]

In fish

editThe role of iodine in marine fish (rich in iodine) and freshwater fish (iodine-deficient) is not completely understood, but it has been reported that freshwater fish are more susceptible to infectious and, in particular, neoplastic and atherosclerotic diseases, than marine fish.[93][94]Marine elasmobranch fishes such as sharks, stingrays etc. are much less affected by cancer than freshwater fishes, and therefore have stimulated medical research to better understand carcinogenesis.[95]

Mechanisms

editIn order for cells to start dividing uncontrollably, genes that regulate cell growth must be dysregulated.[96]Proto-oncogenesare genes that promote cell growth andmitosis,whereastumor suppressor genesdiscourage cell growth, or temporarily halt cell division to carry outDNA repair.Typically, a series of severalmutationsto these genes is required before a normal cell transforms into acancer cell.[10]This concept is sometimes termed "oncoevolution." Mutations to these genes provide the signals for tumor cells to start dividing uncontrollably. But the uncontrolled cell division that characterizes cancer also requires that the dividing cell duplicates all its cellular components to create two daughter cells. The activation of aerobic glycolysis (theWarburg effect), which is not necessarily induced by mutations in proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes,[97]provides most of the building blocks required to duplicate the cellular components of a dividing cell and, therefore, is also essential for carcinogenesis.[61]

Oncogenes

editOncogenespromote cell growth in a variety of ways. Many can producehormones,a "chemical messenger" between cells that encouragemitosis,the effect of which depends on thesignal transductionof the receiving tissue or cells. In other words, when a hormone receptor on a recipient cell is stimulated, the signal is conducted from the surface of the cell to thecell nucleusto affect some change in gene transcription regulation at the nuclear level. Some oncogenes are part of the signal transduction system itself, or the signalreceptorsin cells and tissues themselves, thus controlling the sensitivity to such hormones. Oncogenes often producemitogens,or are involved intranscriptionof DNA inprotein synthesis,which creates theproteinsandenzymesresponsible for producing the products andbiochemicalscells use and interact with.

Mutations in proto-oncogenes, which are the normally quiescent counterparts ofoncogenes,can modify theirexpressionand function, increasing the amount or activity of the product protein. When this happens, the proto-oncogenes becomeoncogenes,and this transition upsets the normal balance ofcell cycleregulation in the cell, making uncontrolled growth possible. The chance of cancer cannot be reduced by removing proto-oncogenes from thegenome,even if this were possible, as they are critical for the growth, repair, andhomeostasisof the organism. It is only when they become mutated that the signals for growth become excessive.

One of the firstoncogenesto be defined incancer researchis theras oncogene.Mutations in the Ras family ofproto-oncogenes(comprising H-Ras, N-Ras, and K-Ras) are very common, being found in 20% to 30% of all human tumors.[98]Ras was originally identified in the Harvey sarcoma virus genome, and researchers were surprised that not only is this gene present in the human genome but also when ligated to a stimulating control element, it could induce cancers in cell line cultures.[99]New mechanisms were proposed recently that the cell transformation during carcinogenesis was decided by the overall threshold of the oncogene networks (such as Ras signaling) but not by the status of the individual oncogene.[100]

Proto-oncogenes

editProto-oncogenes promote cell growth in a variety of ways. Many can producehormones,"chemical messengers" between cells that encourage mitosis, the effect of which depends on thesignal transductionof the receiving tissue or cells. Some are responsible for the signal transduction system and signalreceptorsin cells and tissues themselves, thus controlling the sensitivity to such hormones. They often producemitogens,or are involved intranscriptionof DNA inprotein synthesis,which create theproteinsandenzymesresponsible for producing the products andbiochemicalscells use and interact with.

Mutations in proto-oncogenes can modify theirexpressionand function, increasing the amount or activity of the product protein. When this happens, they becomeoncogenes,and, thus, cells have a higher chance of dividing excessively and uncontrollably. The chance of cancer cannot be reduced by removing proto-oncogenes from thegenome,as they are critical for growth, repair andhomeostasisof the body. It is only when they become mutated that the signals for growth become excessive. It is important to note that a gene possessing a growth-promoting role may increase the carcinogenic potential of a cell, under the condition that all necessary cellular mechanisms that permit growth are activated.[101]This condition also includes the inactivation of specific tumor suppressor genes (see below). If the condition is not fulfilled, the cell may cease to grow and can proceed to die. This makes identification of the stage and type ofcancer cellthat grows under the control of a given oncogene crucial for the development of treatment strategies.

Tumor suppressor genes

editTumor suppressor genescode for anti-proliferation signals and proteins that suppress mitosis and cell growth. Generally, tumor suppressors aretranscription factorsthat are activated by cellularstressor DNA damage. Often DNA damage will cause the presence of free-floating genetic material as well as other signs, and will trigger enzymes and pathways that lead to the activation oftumor suppressor genes.The functions of such genes is to arrest the progression of the cell cycle in order to carry out DNA repair, preventing mutations from being passed on to daughter cells. Thep53protein, one of the most important studied tumor suppressor genes, is a transcription factor activated by many cellular stressors includinghypoxiaandultraviolet radiationdamage.

Despite nearly half of all cancers possibly involving alterations in p53, its tumor suppressor function is poorly understood. p53 clearly has two functions: one a nuclear role as a transcription factor, and the other a cytoplasmic role in regulating the cell cycle, cell division, and apoptosis.

TheWarburg effectis the preferential use of glycolysis for energy to sustain cancer growth. p53 has been shown to regulate the shift from the respiratory to the glycolytic pathway.[102]

However, a mutation can damage the tumor suppressor gene itself, or the signal pathway that activates it, "switching it off". The invariable consequence of this is that DNA repair is hindered or inhibited: DNA damage accumulates without repair, inevitably leading to cancer.

Mutations of tumor suppressor genes that occur ingermlinecells are passed along tooffspring,and increase the likelihood for cancer diagnoses in subsequent generations. Members of these families have increased incidence and decreased latency of multiple tumors. The tumor types are typical for each type of tumor suppressor gene mutation, with some mutations causing particular cancers, and other mutations causing others. The mode of inheritance of mutant tumor suppressors is that an affected member inherits a defective copy from one parent, and a normal copy from the other. For instance, individuals who inherit one mutantp53allele (and are thereforeheterozygousfor mutatedp53) can developmelanomasandpancreatic cancer,known asLi-Fraumeni syndrome.Other inherited tumor suppressor gene syndromes includeRbmutations, linked toretinoblastoma,andAPCgene mutations, linked toadenopolyposis colon cancer.Adenopolyposis colon cancer is associated with thousands of polyps in colon while young, leading tocolon cancerat a relatively early age. Finally, inherited mutations inBRCA1andBRCA2lead to early onset ofbreast cancer.

Development of cancer was proposed in 1971 to depend on at least two mutational events. In what became known as theKnudsontwo-hit hypothesis,an inherited, germ-line mutation in atumor suppressor genewould cause cancer only if another mutation event occurred later in the organism's life, inactivating the otheralleleof thattumor suppressor gene.[103]

Usually, oncogenes aredominant,as they containgain-of-function mutations,while mutated tumor suppressors arerecessive,as they containloss-of-function mutations.Each cell has two copies of the same gene, one from each parent, and under most cases gain of function mutations in just one copy of a particular proto-oncogene is enough to make that gene a true oncogene. On the other hand, loss of function mutations need to happen in both copies of a tumor suppressor gene to render that gene completely non-functional. However, cases exist in which one mutated copy of atumor suppressor genecan render the other,wild-typecopy non-functional. This phenomenon is called thedominant negative effectand is observed in many p53 mutations.

Knudson's two hit model has recently been challenged by several investigators. Inactivation of one allele of some tumor suppressor genes is sufficient to cause tumors. This phenomenon is calledhaploinsufficiencyand has been demonstrated by a number of experimental approaches. Tumors caused byhaploinsufficiencyusually have a later age of onset when compared with those by a two hit process.[104]

Multiple mutations

editIn general, mutations in both types of genes are required for cancer to occur. For example, a mutation limited to one oncogene would be suppressed by normal mitosis control and tumor suppressor genes, firsthypothesisedby theKnudson hypothesis.[8]A mutation to only one tumor suppressor gene would not cause cancer either, due to the presence of many "backup"genes that duplicate its functions. It is only when enough proto-oncogenes have mutated into oncogenes, and enough tumor suppressor genes deactivated or damaged, that the signals for cell growth overwhelm the signals to regulate it, that cell growth quickly spirals out of control.[10]Often, because these genes regulate the processes that prevent most damage to genes themselves, the rate of mutations increases as one gets older, because DNA damage forms afeedbackloop.

Mutation of tumor suppressor genes that are passed on to the next generation of not merely cells, but theiroffspring,can cause increased likelihoods for cancers to be inherited. Members within these families have increased incidence and decreased latency of multiple tumors. The mode of inheritance of mutant tumor suppressors is that affected member inherits a defective copy from one parent, and a normal copy from another. Because mutations in tumor suppressors act in a recessive manner (note, however, there are exceptions), the loss of the normal copy creates the cancerphenotype.For instance, individuals that areheterozygousfor p53 mutations are often victims ofLi-Fraumeni syndrome,and that are heterozygous forRbmutations developretinoblastoma.In similar fashion, mutations in theadenomatous polyposis coligene are linked toadenopolyposis colon cancer,with thousands of polyps in the colon while young, whereas mutations inBRCA1andBRCA2lead to early onset ofbreast cancer.

A new idea announced in 2011 is an extreme version of multiple mutations, calledchromothripsisby its proponents. This idea, affecting only 2–3% of cases of cancer, although up to 25% of bone cancers, involves the catastrophic shattering of a chromosome into tens or hundreds of pieces and then being patched back together incorrectly. This shattering probably takes place when the chromosomes are compacted duringnormal cell division,but the trigger for the shattering is unknown. Under this model, cancer arises as the result of a single, isolated event, rather than the slow accumulation of multiple mutations. [105]

Non-mutagenic carcinogens

editManymutagensare alsocarcinogens,but some carcinogens are not mutagens. Examples of carcinogens that are not mutagens includealcoholandestrogen.These are thought to promote cancers through their stimulating effect on the rate of cellmitosis.Faster rates of mitosis increasingly leave fewer opportunities for repair enzymes to repair damaged DNA duringDNA replication,increasing the likelihood of a genetic mistake. A mistake made during mitosis can lead to the daughter cells' receiving the wrong number ofchromosomes,which leads toaneuploidyand may lead to cancer.

Role of infections

editBacterial

editHelicobacter pylorican causegastric cancer.Although the data varies between different countries, overall about 1% to 3% of people infected withHelicobacter pyloridevelop gastric cancer in their lifetime compared to 0.13% of individuals who have had noH. pyloriinfection.[106][107]H. pyloriinfection is very prevalent. As evaluated in 2002, it is present in the gastric tissues of 74% of middle-aged adults in developing countries and 58% in developed countries.[108]Since 1% to 3% of infected individuals are likely to develop gastric cancer,[109]H. pylori-induced gastric cancer is the third highest cause of worldwide cancer mortality as of 2018.[110]

Infection byH. pyloricauses no symptoms in about 80% of those infected.[111]About 75% of individuals infected withH. pyloridevelopgastritis.[112]Thus, the usual consequence ofH. pyloriinfection is chronic asymptomatic gastritis.[113]Because of the usual lack of symptoms, when gastric cancer is finally diagnosed it is often fairly advanced. More than half of gastric cancer patients have lymph node metastasis when they are initially diagnosed.[114]

The gastritis caused byH. pyloriis accompanied byinflammation,characterized by infiltration ofneutrophilsandmacrophagesto the gastric epithelium, which favors the accumulation ofpro-inflammatory cytokinesandreactive oxygen species/reactive nitrogen species(ROS/RNS).[115]The substantial presence of ROS/RNS causes DNA damage including8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine(8-OHdG).[115]If the infectingH. pyloricarry the cytotoxiccagAgene (present in about 60% of Western isolates and a higher percentage of Asian isolates), they can increase the level of 8-OHdG in gastric cells by 8-fold, while if theH. pylorido not carry the cagA gene, the increase in 8-OHdG is about 4-fold.[116]In addition to theoxidative DNA damage8-OHdG,H. pyloriinfection causes other characteristic DNA damages including DNA double-strand breaks.[117]

H. pylorialso causes manyepigeneticalterations linked to cancer development.[118][119]Theseepigeneticalterations are due toH. pylori-inducedmethylation of CpG sites in promoters of genes[118]andH. pylori-induced altered expression of multiplemicroRNAs.[119]

As reviewed by Santos and Ribeiro[120]H. pyloriinfection is associated with epigenetically reduced efficiency of the DNA repair machinery, which favors the accumulation of mutations and genomic instability as well as gastric carcinogenesis. In particular, Raza et al.[121]showed that expression of two DNA repair proteins,ERCC1andPMS2,was severely reduced onceH. pyloriinfection had progressed to causedyspepsia.Dyspepsia occurs in about 20% of infected individuals.[122]In addition, as reviewed by Raza et al.,[121]human gastric infection withH. pyloricauses epigenetically reduced protein expression of DNA repair proteinsMLH1,MGMTandMRE11.Reduced DNA repair in the presence of increased DNA damage increases carcinogenic mutations and is likely a significant cause ofH. pyloricarcinogenesis.

Other bacteria might also play a role in carcinogenesis. Checkpoint control of thecell cycleandapoptosisbyp53is inhibited by themycoplasmabacterium,[123]allowing cells withDNA damageto "run an apoptotic red light" and proceed through the cell cycle.

Viral

editFurthermore, many cancers originate from aviralinfection;this is especially true in animals such asbirds,but less so inhumans.12% of human cancers can be attributed to a viral infection.[124]The mode of virally induced tumors can be divided into two,acutely transformingorslowly transforming.In acutely transforming viruses, the viral particles carry a gene that encodes for an overactive oncogene called viral-oncogene (v-onc), and the infected cell is transformed as soon as v-onc is expressed. In contrast, in slowly transforming viruses, the virus genome is inserted, especially as viral genome insertion is an obligatory part ofretroviruses,near a proto-oncogene in the host genome. The viralpromoteror other transcription regulation elements, in turn, cause over-expression of that proto-oncogene, which, in turn, induces uncontrolled cellular proliferation. Because viral genome insertion is not specific to proto-oncogenes and the chance of insertion near that proto-oncogene is low, slowly transforming viruses have very long tumor latency compared to acutely transforming virus, which already carries the viral-oncogene.

Viruses that are known to cause cancer such asHPV(cervical cancer),Hepatitis B(liver cancer), andEBV(a type oflymphoma), are all DNA viruses. It is thought that when the virus infects a cell, it inserts a part of its own DNA near the cell growth genes, causing cell division. The group of changed cells that are formed from the first cell dividing all have the same viral DNA near the cell growth genes. The group of changed cells are now special because one of the normal controls on growth has been lost.

Depending on their location, cells can be damaged through radiation, chemicals from cigarette smoke, and inflammation from bacterial infection or other viruses. Each cell has a chance of damage. Cells often die if they are damaged, through failure of a vital process or the immune system, however, sometimes damage will knock out a single cancer gene. In an old person, there are thousands, tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands of knocked-out cells. The chance that any one would form a cancer is very low.[citation needed]

When the damage occurs in any area of changed cells, something different occurs. Each of the cells has the potential for growth. The changed cells will divide quicker when the area is damaged by physical, chemical, or viral agents. Avicious circlehas been set up: Damaging the area will cause the changed cells to divide, causing a greater likelihood that they will experience knock-outs.

This model of carcinogenesis is popular because it explains why cancers grow. It would be expected that cells that are damaged through radiation would die or at least be worse off because they have fewer genes working; viruses increase the number of genes working.

One thought is that we may end up with thousands of vaccines to prevent every virus that can change our cells. Viruses can have different effects on different parts of the body. It may be possible to prevent a number of different cancers by immunizing against one viral agent. It is likely that HPV, for instance, has a role in cancers of the mucous membranes of the mouth.

Helminthiasis

editCertain parasitic worms are known to be carcinogenic.[125]These include:

- Clonorchis sinensis(the organism causingClonorchiasis) andOpisthorchis viverrini(causingOpisthorchiasis) are associated withcholangiocarcinoma.[126]

- Schistosomaspecies(the organisms causingSchistosomiasis) is associated withbladder cancer.

Epigenetics

editEpigeneticsis the study of the regulation of gene expression through chemical, non-mutational changes in DNA structure. The theory ofepigeneticsin cancer pathogenesis is that non-mutational changes to DNA can lead to alterations in gene expression. Normally,oncogenesare silent, for example, because ofDNA methylation.Loss of that methylation can induce the aberrant expression ofoncogenes,leading to cancer pathogenesis. Known mechanisms of epigenetic change includeDNA methylation,and methylation or acetylation ofhistoneproteins bound to chromosomal DNA at specific locations. Classes of medications, known asHDAC inhibitorsandDNA methyltransferaseinhibitors, can re-regulate the epigenetic signaling in thecancer cell.

Epimutationsinclude methylations or demethylations of theCpG islandsof thepromoterregions of genes, which result in repression or de-repression, respectively of gene expression.[127][128][129]Epimutations can also occur by acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation or other alterations to histones, creating ahistone codethat represses or activates gene expression, and such histone epimutations can be important epigenetic factors in cancer.[130][131]In addition, carcinogenic epimutation can occur through alterations of chromosome architecture caused by proteins such asHMGA2.[132]A further source of epimutation is due to increased or decreased expression ofmicroRNAs(miRNAs). For example, extra expression of miR-137 can cause downregulation of expression of 491 genes, and miR-137 is epigenetically silenced in 32% of colorectal cancers>[15]

Cancer stem cells

editA new way of looking at carcinogenesis comes from integrating the ideas ofdevelopmental biologyintooncology.Thecancer stem cellhypothesisproposes that the different kinds of cells in aheterogeneoustumor arise from a single cell, termed Cancer Stem Cell. Cancer stem cells may arise from transformation ofadult stem cellsordifferentiatedcells within a body. These cells persist as a subcomponent of the tumor and retain key stem cell properties. They give rise to a variety of cells, are capable of self-renewal andhomeostaticcontrol.[133]Furthermore, therelapseof cancer and the emergence ofmetastasisare also attributed to these cells. Thecancer stem cellhypothesisdoes not contradict earlier concepts of carcinogenesis. The cancer stem cell hypothesis has been a proposed mechanism that contributes totumour heterogeneity.

Clonal evolution

editWhile genetic andepigeneticalterations in tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes change the behavior of cells, those alterations, in the end, result in cancer through their effects on the population ofneoplasticcells and their microenvironment.[67]Mutant cells in neoplasms compete for space and resources. Thus, a clone with a mutation in a tumor suppressor gene or oncogene will expand only in a neoplasm if that mutation gives the clone a competitive advantage over the other clones and normal cells in its microenvironment.[134]Thus, the process of carcinogenesis is formally a process of Darwinianevolution,known assomatic or clonal evolution.[68]Furthermore, in light of the Darwinistic mechanisms of carcinogenesis, it has been theorized that the various forms of cancer can be categorized as pubertal and gerontological. Anthropological research is currently being conducted on cancer as a natural evolutionary process through which natural selection destroys environmentally inferior phenotypes while supporting others. According to this theory, cancer comes in two separate types: from birth to the end of puberty (approximately age 20) teleologically inclined toward supportive group dynamics, and from mid-life to death (approximately age 40+) teleologically inclined away from overpopulated group dynamics.[citation needed]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^Majérus, Marie-Ange (1 July 2022)."The cause of cancer: The unifying theory".Advances in Cancer Biology - Metastasis.4:100034.doi:10.1016/j.adcanc.2022.100034.ISSN2667-3940.S2CID247145082.

- ^Nowell, Peter C. (1 October 1976)."The Clonal Evolution of Tumor Cell Populations: Acquired genetic lability permits stepwise selection of variant sublines and underlies tumor progression".Science.194(4260): 23–28.Bibcode:1976Sci...194...23N.doi:10.1126/science.959840.ISSN0036-8075.PMID959840.S2CID38445059.

- ^Hanahan, Douglas; Weinberg, Robert A (7 January 2000)."The Hallmarks of Cancer".Cell.100(1): 57–70.doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9.ISSN0092-8674.PMID10647931.S2CID1478778.

- ^Hahn, William C.; Weinberg, Robert A. (14 November 2002)."Rules for Making Human Tumor Cells".New England Journal of Medicine.347(20): 1593–1603.doi:10.1056/NEJMra021902.ISSN0028-4793.PMID12432047.

- ^Calkins, Gary N. (11 December 1914)."Zur Frage der Entstehung maligner Tumoren. By Th. Boveri. Jena, Gustav Fischer. 1914. 64 pages".Science.40(1041): 857–859.doi:10.1126/science.40.1041.857.ISSN0036-8075.

- ^Tomasetti C, Li L, Vogelstein B (23 March 2017)."Stem cell divisions, somatic mutations, cancer etiology, and cancer prevention".Science.355(6331): 1330–1334.Bibcode:2017Sci...355.1330T.doi:10.1126/science.aaf9011.PMC5852673.PMID28336671.

- ^Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjöblom T, Leary RJ, et al. (November 2007). "The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers".Science.318(5853): 1108–13.Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1108W.CiteSeerX10.1.1.218.5477.doi:10.1126/science.1145720.PMID17932254.S2CID7586573.

- ^abKnudson AG (November 2001). "Two genetic hits (more or less) to cancer".Nature Reviews. Cancer.1(2): 157–62.doi:10.1038/35101031.PMID11905807.S2CID20201610.

- ^Fearon ER, Vogelstein B (June 1990)."A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis".Cell.61(5): 759–67.doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-I.PMID2188735.S2CID22975880.

- ^abcBelikov AV (September 2017)."The number of key carcinogenic events can be predicted from cancer incidence".Scientific Reports.7(1): 12170.Bibcode:2017NatSR...712170B.doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12448-7.PMC5610194.PMID28939880.

- ^Belikov AV, Vyatkin A, Leonov SV (6 August 2021)."The Erlang distribution approximates the age distribution of incidence of childhood and young adulthood cancers".PeerJ.9:e11976.doi:10.7717/peerj.11976.PMC8351573.PMID34434669.

- ^Vyatkin, Alexey D.; Otnyukov, Danila V.; Leonov, Sergey V.; Belikov, Aleksey V. (14 January 2022)."Comprehensive patient-level classification and quantification of driver events in TCGA PanCanAtlas cohorts".PLOS Genetics.18(1): e1009996.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1009996.PMC8759692.PMID35030162.

- ^Croce CM (January 2008). "Oncogenes and cancer".The New England Journal of Medicine.358(5): 502–11.doi:10.1056/NEJMra072367.PMID18234754.

- ^Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM (February 2005). "Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs".Nature.433(7027): 769–73.Bibcode:2005Natur.433..769L.doi:10.1038/nature03315.PMID15685193.S2CID4430576.

- ^abBalaguer F, Link A, Lozano JJ, Cuatrecasas M, Nagasaka T, Boland CR, Goel A (August 2010)."Epigenetic silencing of miR-137 is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis".Cancer Research.70(16): 6609–18.doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0622.PMC2922409.PMID20682795.

- ^"How Chromosome Imbalances Can Drive Cancer | Harvard Medical School".hms.harvard.edu.6 July 2023.Retrieved2 April2024.

- ^Kastan MB (April 2008)."DNA damage responses: mechanisms and roles in human disease: 2007 G.H.A. Clowes Memorial Award Lecture".Molecular Cancer Research.6(4): 517–24.doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0020.PMID18403632.

- ^abCunningham FH, Fiebelkorn S, Johnson M, Meredith C (November 2011). "A novel application of the Margin of Exposure approach: segregation of tobacco smoke toxicants".Food and Chemical Toxicology.49(11): 2921–33.doi:10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.019.PMID21802474.

- ^Kanavy HE, Gerstenblith MR (December 2011). "Ultraviolet radiation and melanoma".Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery.30(4): 222–8.doi:10.1016/j.sder.2011.08.003(inactive 1 November 2024).PMID22123420.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^Handa O, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T (2011)."Redox biology and gastric carcinogenesis: the role of Helicobacter pylori".Redox Report.16(1): 1–7.doi:10.1179/174329211X12968219310756.PMC6837368.PMID21605492.

- ^Smela ME, Hamm ML, Henderson PT, Harris CM, Harris TM, Essigmann JM (May 2002)."The aflatoxin B(1) formamidopyrimidine adduct plays a major role in causing the types of mutations observed in human hepatocellular carcinoma".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.99(10): 6655–60.Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.6655S.doi:10.1073/pnas.102167699.PMC124458.PMID12011430.

- ^Katsurano M, Niwa T, Yasui Y, Shigematsu Y, Yamashita S, Takeshima H, Lee MS, Kim YJ, Tanaka T, Ushijima T (January 2012)."Early-stage formation of an epigenetic field defect in a mouse colitis model, and non-essential roles of T- and B-cells in DNA methylation induction".Oncogene.31(3): 342–51.doi:10.1038/onc.2011.241.PMID21685942.

- ^Bernstein C, Holubec H, Bhattacharyya AK, Nguyen H, Payne CM, Zaitlin B, Bernstein H (August 2011)."Carcinogenicity of deoxycholate, a secondary bile acid".Archives of Toxicology.85(8): 863–71.doi:10.1007/s00204-011-0648-7.PMC3149672.PMID21267546.

- ^Malkin D (April 2011)."Li-fraumeni syndrome".Genes & Cancer.2(4): 475–84.doi:10.1177/1947601911413466.PMC3135649.PMID21779515.

- ^Fearon ER (November 1997). "Human cancer syndromes: clues to the origin and nature of cancer".Science.278(5340): 1043–50.Bibcode:1997Sci...278.1043F.doi:10.1126/science.278.5340.1043.PMID9353177.

- ^Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K (July 2000)."Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland".The New England Journal of Medicine.343(2): 78–85.doi:10.1056/NEJM200007133430201.PMID10891514.

- ^Halford S, Rowan A, Sawyer E, Talbot I, Tomlinson I (June 2005)."O(6)-methylguanine methyltransferase in colorectal cancers: detection of mutations, loss of expression, and weak association with G:C>A:T transitions".Gut.54(6): 797–802.doi:10.1136/gut.2004.059535.PMC1774551.PMID15888787.

- ^abNarayanan L, Fritzell JA, Baker SM, Liskay RM, Glazer PM (April 1997)."Elevated levels of mutation in multiple tissues of mice deficient in the DNA mismatch repair gene Pms2".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.94(7): 3122–7.Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.3122N.doi:10.1073/pnas.94.7.3122.PMC20332.PMID9096356.

- ^abHegan DC, Narayanan L, Jirik FR, Edelmann W, Liskay RM, Glazer PM (December 2006)."Differing patterns of genetic instability in mice deficient in the mismatch repair genes Pms2, Mlh1, Msh2, Msh3 and Msh6".Carcinogenesis.27(12): 2402–8.doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl079.PMC2612936.PMID16728433.

- ^abTutt AN, van Oostrom CT, Ross GM, van Steeg H, Ashworth A (March 2002)."Disruption of Brca2 increases the spontaneous mutation rate in vivo: synergism with ionizing radiation".EMBO Reports.3(3): 255–60.doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvf037.PMC1084010.PMID11850397.

- ^German J (March 1969)."Bloom's syndrome. I. Genetical and clinical observations in the first twenty-seven patients".American Journal of Human Genetics.21(2): 196–227.PMC1706430.PMID5770175.

- ^O'Hagan HM, Mohammad HP, Baylin SB (August 2008). Lee JT (ed.)."Double strand breaks can initiate gene silencing and SIRT1-dependent onset of DNA methylation in an exogenous promoter CpG island".PLOS Genetics.4(8): e1000155.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000155.PMC2491723.PMID18704159.

- ^Cuozzo C, Porcellini A, Angrisano T, Morano A, Lee B, Di Pardo A, Messina S, Iuliano R, Fusco A, Santillo MR, Muller MT, Chiariotti L, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV (July 2007)."DNA damage, homology-directed repair, and DNA methylation".PLOS Genetics.3(7): e110.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030110.PMC1913100.PMID17616978.

- ^Villeneuve PJ, Mao Y (November 1994). "Lifetime probability of developing lung cancer, by smoking status, Canada".Canadian Journal of Public Health.85(6): 385–8.PMID7895211.

- ^Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, et al. (March 2012)."Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing".The New England Journal of Medicine.366(10): 883–92.doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1113205.PMC4878653.PMID22397650.

- ^abLópez-Lázaro M (August 2015)."Stem cell division theory of cancer".Cell Cycle.14(16): 2547–8.doi:10.1080/15384101.2015.1062330.PMC5242319.PMID26090957.

- ^abcLópez-Lázaro M (May 2015)."The migration ability of stem cells can explain the existence of cancer of unknown primary site. Rethinking metastasis".Oncoscience.2(5): 467–75.doi:10.18632/oncoscience.159.PMC4468332.PMID26097879.

- ^Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B (January 2015)."Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions".Science.347(6217): 78–81.doi:10.1126/science.1260825.PMC4446723.PMID25554788.

- ^Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W (September 1953)."Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin".Cancer.6(5): 963–8.doi:10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::AID-CNCR2820060515>3.0.CO;2-Q.PMID13094644.S2CID6736946.

- ^Bernstein C, Bernstein H, Payne CM, Dvorak K, Garewal H (February 2008)."Field defects in progression to gastrointestinal tract cancers".review.Cancer Letters.260(1–2): 1–10.doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2007.11.027.PMC2744582.PMID18164807.

- ^Nguyen H, Loustaunau C, Facista A, Ramsey L, Hassounah N, Taylor H, Krouse R, Payne CM, Tsikitis VL, Goldschmid S, Banerjee B, Perini RF, Bernstein C (2010)."Deficient Pms2, ERCC1, Ku86, CcOI in field defects during progression to colon cancer".Journal of Visualized Experiments(41): 1931.doi:10.3791/1931.PMC3149991.PMID20689513.

- ^Rubin H (March 2011). "Fields and field cancerization: the preneoplastic origins of cancer: asymptomatic hyperplastic fields are precursors of neoplasia, and their progression to tumors can be tracked by saturation density in culture".BioEssays.33(3): 224–31.doi:10.1002/bies.201000067.PMID21254148.S2CID44981539.

- ^Tsao JL, Yatabe Y, Salovaara R, Järvinen HJ, Mecklin JP, Aaltonen LA, Tavaré S, Shibata D (February 2000)."Genetic reconstruction of individual colorectal tumor histories".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.97(3): 1236–41.Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.1236T.doi:10.1073/pnas.97.3.1236.PMC15581.PMID10655514.

- ^abcVogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Kinzler KW (March 2013)."Cancer genome landscapes".review.Science.339(6127): 1546–58.Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1546V.doi:10.1126/science.1235122.PMC3749880.PMID23539594.

- ^Shen L, Kondo Y, Rosner GL, Xiao L, Hernandez NS, Vilaythong J, Houlihan PS, Krouse RS, Prasad AR, Einspahr JG, Buckmeier J, Alberts DS, Hamilton SR, Issa JP (September 2005)."MGMT promoter methylation and field defect in sporadic colorectal cancer".Journal of the National Cancer Institute.97(18): 1330–8.doi:10.1093/jnci/dji275.PMID16174854.

- ^abLee KH, Lee JS, Nam JH, Choi C, Lee MC, Park CS, Juhng SW, Lee JH (October 2011). "Promoter methylation status of hMLH1, hMSH2, and MGMT genes in colorectal cancer associated with adenoma-carcinoma sequence".Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery.396(7): 1017–26.doi:10.1007/s00423-011-0812-9.PMID21706233.S2CID8069716.

- ^Svrcek M, Buhard O, Colas C, Coulet F, Dumont S, Massaoudi I, et al. (November 2010). "Methylation tolerance due to an O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) field defect in the colonic mucosa: an initiating step in the development of mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancers".Gut.59(11): 1516–26.doi:10.1136/gut.2009.194787.PMID20947886.S2CID206950452.

- ^abcdFacista A, Nguyen H, Lewis C, Prasad AR, Ramsey L, Zaitlin B, Nfonsam V, Krouse RS, Bernstein H, Payne CM, Stern S, Oatman N, Banerjee B, Bernstein C (April 2012)."Deficient expression of DNA repair enzymes in early progression to sporadic colon cancer".Genome Integrity.3(1): 3.doi:10.1186/2041-9414-3-3.PMC3351028.PMID22494821.

- ^Paluszczak J, Misiak P, Wierzbicka M, Woźniak A, Baer-Dubowska W (February 2011). "Frequent hypermethylation of DAPK, RARbeta, MGMT, RASSF1A and FHIT in laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas and adjacent normal mucosa".Oral Oncology.47(2): 104–7.doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.11.006.PMID21147548.

- ^Zuo C, Zhang H, Spencer HJ, Vural E, Suen JY, Schichman SA, Smoller BR, Kokoska MS, Fan CY (October 2009). "Increased microsatellite instability and epigenetic inactivation of the hMLH1 gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma".Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.141(4): 484–90.doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.07.007.PMID19786217.S2CID8357370.

- ^Tawfik HM, El-Maqsoud NM, Hak BH, El-Sherbiny YM (2011). "Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: mismatch repair immunohistochemistry and promoter hypermethylation of hMLH1 gene".American Journal of Otolaryngology.32(6): 528–36.doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.11.005.PMID21353335.

- ^Zou XP, Zhang B, Zhang XQ, Chen M, Cao J, Liu WJ (November 2009). "Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in early gastric adenocarcinoma and precancerous lesions".Human Pathology.40(11): 1534–42.doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.029.PMID19695681.

- ^Wani M, Afroze D, Makhdoomi M, Hamid I, Wani B, Bhat G, Wani R, Wani K (2012)."Promoter methylation status of DNA repair gene (hMLH1) in gastric carcinoma patients of the Kashmir valley"(PDF).Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.13(8): 4177–81.doi:10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.4177.PMID23098428.

- ^Agarwal A, Polineni R, Hussein Z, Vigoda I, Bhagat TD, Bhattacharyya S, Maitra A, Verma A (2012)."Role of epigenetic alterations in the pathogenesis of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma".International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology.5(5): 382–96.PMC3396065.PMID22808291.Review.

- ^Hofstad B, Vatn MH, Andersen SN, Huitfeldt HS, Rognum T, Larsen S, Osnes M (September 1996)."Growth of colorectal polyps: redetection and evaluation of unresected polyps for a period of three years".Gut.39(3): 449–56.doi:10.1136/gut.39.3.449.PMC1383355.PMID8949653.

- ^Schmitt MW, Prindle MJ, Loeb LA (September 2012)."Implications of genetic heterogeneity in cancer".Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.1267(1): 110–6.Bibcode:2012NYASA1267..110S.doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06590.x.PMC3674777.PMID22954224.

- ^Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, et al. (February 2001)."Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome".Nature.409(6822): 860–921.Bibcode:2001Natur.409..860L.doi:10.1038/35057062.hdl:2027.42/62798.PMID11237011.

- ^Yost SE, Smith EN, Schwab RB, Bao L, Jung H, Wang X, Voest E, Pierce JP, Messer K, Parker BA, Harismendy O, Frazer KA (August 2012)."Identification of high-confidence somatic mutations in whole genome sequence of formalin-fixed breast cancer specimens".Nucleic Acids Research.40(14): e107.doi:10.1093/nar/gks299.PMC3413110.PMID22492626.

- ^Berger MF, Hodis E, Heffernan TP, Deribe YL, Lawrence MS, Protopopov A, et al. (May 2012)."Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations".Nature.485(7399): 502–6.Bibcode:2012Natur.485..502B.doi:10.1038/nature11071.PMC3367798.PMID22622578.

- ^Rasnick D, Duesberg PH (June 1999)."How aneuploidy affects metabolic control and causes cancer".The Biochemical Journal.340(3): 621–30.doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3400621.PMC1220292.PMID10359645.

- ^abcLópez-Lázaro M (March 2010)."A new view of carcinogenesis and an alternative approach to cancer therapy".Molecular Medicine.16(3–4): 144–53.doi:10.2119/molmed.2009.00162.PMC2802554.PMID20062820.

- ^Juutilainen J, Herrala M, Luukkonen J, Naarala J, Hore PJ (May 2018)."Magnetocarcinogenesis: is there a mechanism for carcinogenic effects of weak magnetic fields?".Proceedings. Biological Sciences.285(1879): 20180590.doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0590.PMC5998098.PMID29794049.

- ^Soto AM, Sonnenschein C (October 2004). "The somatic mutation theory of cancer: growing problems with the paradigm?".BioEssays.26(10): 1097–107.doi:10.1002/bies.20087.PMID15382143.

- ^Davies PC, Lineweaver CH (February 2011)."Cancer tumors as Metazoa 1.0: tapping genes of ancient ancestors".Physical Biology.8(1): 015001.Bibcode:2011PhBio...8a5001D.doi:10.1088/1478-3975/8/1/015001.PMC3148211.PMID21301065.

- ^Dean, Tim."Cancer resembles life 1 billion years ago, say astrobiologists",Australian Life Scientist,8 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^Sterrer, W (August 2016)."Cancer - Mutational Resurrection of Prokaryote Endofossils"(PDF).Cancer Hypotheses.1(1): 1–15. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 3 March 2022.Retrieved8 May2019.

- ^abNowell PC (October 1976). "The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations".Science.194(4260): 23–8.Bibcode:1976Sci...194...23N.doi:10.1126/science.959840.PMID959840.S2CID38445059.

- ^abMerlo LM, Pepper JW, Reid BJ, Maley CC (December 2006). "Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process".Nature Reviews. Cancer.6(12): 924–35.doi:10.1038/nrc2013.PMID17109012.S2CID8040576.

- ^Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (January 2000)."The hallmarks of cancer".Cell.100(1): 57–70.doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9.PMID10647931.

- ^Cho RW, Clarke MF (February 2008). "Recent advances in cancer stem cells".Current Opinion in Genetics & Development.18(1): 48–53.doi:10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.017.PMID18356041.

- ^Taniguchi K, Wu LW, Grivennikov SI, de Jong PR, Lian I, Yu FX, Wang K, Ho SB, Boland BS, Chang JT, Sandborn WJ, Hardiman G, Raz E, Maehara Y, Yoshimura A, Zucman-Rossi J, Guan KL, Karin M (March 2015)."A gp130-Src-YAP module links inflammation to epithelial regeneration".Nature.519(7541): 57–62.Bibcode:2015Natur.519...57T.doi:10.1038/nature14228.PMC4447318.PMID25731159.

- ^You H, Lei P, Andreadis ST (December 2013)."JNK is a novel regulator of intercellular adhesion".Tissue Barriers.1(5): e26845.doi:10.4161/tisb.26845.PMC3942331.PMID24868495.

- ^Busillo JM, Azzam KM, Cidlowski JA (November 2011)."Glucocorticoids sensitize the innate immune system through regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.286(44): 38703–13.doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.275370.PMC3207479.PMID21940629.

- ^Wang Y, Bugatti M, Ulland TK, Vermi W, Gilfillan S, Colonna M (March 2016)."Nonredundant roles of keratinocyte-derived IL-34 and neutrophil-derived CSF1 in Langerhans cell renewal in the steady state and during inflammation".European Journal of Immunology.46(3): 552–9.doi:10.1002/eji.201545917.PMC5658206.PMID26634935.

- ^Siqueira Mietto B, Kroner A, Girolami EI, Santos-Nogueira E, Zhang J, David S (December 2015)."Role of IL-10 in Resolution of Inflammation and Functional Recovery after Peripheral Nerve Injury".The Journal of Neuroscience.35(50): 16431–42.doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2119-15.2015.PMC6605511.PMID26674868.

- ^Seifert AW, Maden M (2014). "New insights into vertebrate skin regeneration".International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology.Vol. 310. pp. 129–69.doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800180-6.00004-9.ISBN978-0-12-800180-6.PMID24725426.S2CID22554281.

- ^Kwon MJ, Shin HY, Cui Y, Kim H, Thi AH, Choi JY, Kim EY, Hwang DH, Kim BG (December 2015)."CCL2 Mediates Neuron-Macrophage Interactions to Drive Proregenerative Macrophage Activation Following Preconditioning Injury".The Journal of Neuroscience.35(48): 15934–47.doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1924-15.2015.PMC6605453.PMID26631474.

- ^Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T (January 2013)."Endogenous modulators of inflammatory cell recruitment".Trends in Immunology.34(1): 1–6.doi:10.1016/j.it.2012.08.003.PMC3703146.PMID22951309.

- ^Nelson AM, Katseff AS, Ratliff TS, Garza LA (February 2016)."Interleukin 6 and STAT3 regulate p63 isoform expression in keratinocytes during regeneration".Experimental Dermatology.25(2): 155–7.doi:10.1111/exd.12896.PMC4724264.PMID26566817.

- ^Vidal PM, Lemmens E, Dooley D, Hendrix S (February 2013). "The role of" anti-inflammatory "cytokines in axon regeneration".Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews.24(1): 1–12.doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.08.008.PMID22985997.

- ^Hsueh YY, Chang YJ, Huang CW, Handayani F, Chiang YL, Fan SC, Ho CJ, Kuo YM, Yang SH, Chen YL, Lin SC, Huang CC, Wu CC (October 2015)."Synergy of endothelial and neural progenitor cells from adipose-derived stem cells to preserve neurovascular structures in rat hypoxic-ischemic brain injury".Scientific Reports.5:14985.Bibcode:2015NatSR...514985H.doi:10.1038/srep14985.PMC4597209.PMID26447335.

- ^Yaniv M (September 2014). "Chromatin remodeling: from transcription to cancer".Cancer Genetics.207(9): 352–7.doi:10.1016/j.cancergen.2014.03.006.PMID24825771.

- ^Zhang X, He N, Gu D, Wickliffe J, Salazar J, Boldogh I, Xie J (October 2015)."Genetic Evidence for XPC-KRAS Interactions During Lung Cancer Development".Journal of Genetics and Genomics = Yi Chuan Xue Bao.42(10): 589–96.doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2015.09.006.PMC4643398.PMID26554912.

- ^Dubois-Pot-Schneider H, Fekir K, Coulouarn C, Glaise D, Aninat C, Jarnouen K, Le Guével R, Kubo T, Ishida S, Morel F, Corlu A (December 2014). "Inflammatory cytokines promote the retrodifferentiation of tumor-derived hepatocyte-like cells to progenitor cells".Hepatology.60(6): 2077–90.doi:10.1002/hep.27353.PMID25098666.S2CID11182192.

- ^Finkin S, Yuan D, Stein I, Taniguchi K, Weber A, Unger K, et al. (December 2015)."Ectopic lymphoid structures function as microniches for tumor progenitor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma".Nature Immunology.16(12): 1235–44.doi:10.1038/ni.3290.PMC4653079.PMID26502405.

- ^Beane JE, Mazzilli SA, Campbell JD, Duclos G, Krysan K, Moy C, et al. (April 2019)."Molecular subtyping reveals immune alterations associated with progression of bronchial premalignant lesions".Nature Communications.10(1): 1856.Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1856B.doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09834-2.PMC6478943.PMID31015447.

- ^Maoz A, Merenstein C, Koga Y, Potter A, Gower AC, Liu G, et al. (September 2021)."Elevated T cell repertoire diversity is associated with progression of lung squamous cell premalignant lesions".Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer.9(9): e002647.doi:10.1136/jitc-2021-002647.PMC8477334.PMID34580161.

- ^abVlahopoulos SA, Cen O, Hengen N, Agan J, Moschovi M, Critselis E, Adamaki M, Bacopoulou F, Copland JA, Boldogh I, Karin M, Chrousos GP (August 2015)."Dynamic aberrant NF-κB spurs tumorigenesis: a new model encompassing the microenvironment".Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews.26(4): 389–403.doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.06.001.PMC4526340.PMID26119834.

- ^Grivennikov SI, Karin M (February 2010)."Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer".Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews.21(1): 11–9.doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.005.PMC2834864.PMID20018552.

- ^Rieger S, Zhao H, Martin P, Abe K, Lisse TS (January 2015)."The role of nuclear hormone receptors in cutaneous wound repair".Cell Biochemistry and Function.33(1): 1–13.doi:10.1002/cbf.3086.PMC4357276.PMID25529612.

- ^Lu X, Yarbrough WG (February 2015). "Negative regulation of RelA phosphorylation: emerging players and their roles in cancer".Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews.26(1): 7–13.doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.09.003.PMID25438737.

- ^Sionov RV, Fridlender ZG, Granot Z (December 2015)."The Multifaceted Roles Neutrophils Play in the Tumor Microenvironment".Cancer Microenvironment.8(3): 125–58.doi:10.1007/s12307-014-0147-5.PMC4714999.PMID24895166.

- ^Venturi, Sebastiano (2011). "Evolutionary Significance of Iodine".Current Chemical Biology.5(3): 155–162.doi:10.2174/187231311796765012.ISSN1872-3136.

- ^Venturi S (2014). "Iodine, PUFAs and Iodolipids in Health and Disease: An Evolutionary Perspective".Human Evolution.29(1–3): 185–205.ISSN0393-9375.

- ^Walsh CJ, Luer CA, Bodine AB, Smith CA, Cox HL, Noyes DR, Maura G (December 2006)."Elasmobranch immune cells as a source of novel tumor cell inhibitors: Implications for public health".Integrative and Comparative Biology.46(6): 1072–1081.doi:10.1093/icb/icl041.PMC2664222.PMID19343108.

- ^Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW (August 2004). "Cancer genes and the pathways they control".Nature Medicine.10(8): 789–99.doi:10.1038/nm1087.PMID15286780.S2CID205383514.

- ^Brand KA, Hermfisse U (April 1997)."Aerobic glycolysis by proliferating cells: a protective strategy against reactive oxygen species".FASEB Journal.11(5): 388–95.doi:10.1096/fasebj.11.5.9141507.PMID9141507.S2CID16745745.

- ^Bos JL (September 1989)."ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review".Cancer Research.49(17): 4682–9.PMID2547513.