TheWen Xuan([wə̌n.ɕɥɛ̀n];Chinese:Văn tuyển), usually translatedSelections of Refined Literature,is one of the earliest and most importantanthologiesofChinese poetryandliterature,and is one of the world's oldest literary anthologies to be arranged by topic. It is a selection of what were judged to be the best poetic and prose pieces from the lateWarring States period(c. 300 BC) to the earlyLiang dynasty(c. AD 500), excluding the Chinese Classics and philosophical texts.[1]TheWen Xuanpreserves most of the greatestfurhapsodyandshipoetrypieces from theQinandHan dynasties,and for much of pre-modern history was one of the primary sources of literary knowledge for educated Chinese.[2]

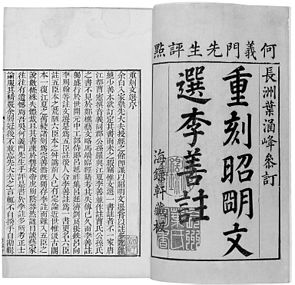

An edition of theWen Xuanprinted around 1700 | |

| Author | (compiler)Xiao Tong,Crown Prince of Liang |

|---|---|

| Original title | Văn tuyển |

| Wen xuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Wenxuan"in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Văn tuyển | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Văn tuyển | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Selections of [Refined] Literature" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TheWen Xuanwas compiled between AD 520 and 530 in the city of Jiankang (modernNanjing) during theLiang dynastybyXiao Tong,the eldest son ofEmperor Wu of Liang,and a group of scholars he had assembled. The Liang dynasty, though short-lived, was a period of intense literary activity, and the ruling Xiao family ensured that eminent writers and scholars were frequently invited to the imperial and provincial courts.[3]As Crown Prince, Xiao Tong received the best classical Chinese education available and began selecting pieces for his new anthology in his early twenties. TheWen Xuancontains 761 separate pieces organized into 37 literary categories, the largest and most well known being "Rhapsodies" (fu) and "Lyric Poetry" (shi).

Study of theWen Xuanenjoyed immense popularity during theTang dynasty(618–907), and its study rivalled that of theFive Classicsduring that period. TheWen Xuanwas required reading for any aspiring scholar and official even into theSong dynasty.Throughout theYuanandMing dynastiesstudy of theWen Xuanlapsed out of popularity, though the great philologists of theQing dynastyrevived its study to some extent.

Three volumes of the first full English translation of theWen Xuanhave been published by the American sinologistDavid R. Knechtges,professor emeritus of Chinese at theUniversity of Washington,who aims to eventually complete the translation in five additional volumes.

History

editCompilation

editTheWen Xuanwas compiled during the 520s byXiao Tong—the son and heir apparent ofEmperor Wu of Liang—at the Liang capital Jiankang (modernNanjing) with the assistance of his closest friends and associates. Xiao was a precocious child and received an excellent classical Chinese education. His two official biographies both state that by age four he had memorized theFive Classicsand at age eight gave a relatively competent lecture on theClassic of Filial Pietyto a group of assembled scholars.[4]As Xiao matured, he developed a love of scholarship and books, and by his early teenage years the library of the Eastern Palace – the Crown Prince's official residence – contained over 30,000 volumes.

Xiao spent much of his leisure time in the company of the leading Chinese scholars of his day, and their serious discussions of literature impelled the creation of theWen Xuan.His main purpose in creating theWen Xuanwas the creation of a suitable anthology of the best individual works ofbelles-lettresavailable, and he ignored philosophical works in favor of aesthetically beautiful poetry and other writings.[5]In theWen Xuan's preface, Xiao explains that four major types of Chinese writing were deliberately excluded from it: 1) the traditional "Classics" that were anciently attributed to theDuke of ZhouandConfucius,such as theClassic of Changes(I Ching)and theClassic of Poetry(Shi jing);2) writings of philosophical "masters", such as theLaozi (Dao De Jing),theZhuangzi,and theMencius;3) collections of rhetorical speeches, such as theIntrigues of the Warring States(Zhan guo ce);and 4) historical narratives and chronicles such as theZuo Tradition(Zuo zhuan).[6]After Xiao Tong's death in 531 he was given the posthumous nameZhaomingChiêu minh ( "Resplendent Brilliance" ), and so the collection came to be known as the "ZhaomingWen xuan".[7]Despite its massive influence on Chinese literature, Xiao's categories and editorial choices have occasionally been criticized throughout Chinese history for a number of odd or illogical choices.[8]

Manuscripts

editA large number of manuscripts and fragments of theWen Xuanhave survived to modern times. Many were discovered among theDunhuang manuscriptsand are held in various museums around the world, particularly at theBritish LibraryandBibliothèque Nationale de France,[9]as well as inJapan,where theWen Xuanwas well known from at least the 7th century.[10]One Japanese manuscript, held in theEisei Bunko Museum,is a rare fragment of aWen Xuancommentary that may predate Li Shan's authoritative commentary from the mid-6th century.[11]

Contents

editTheWen Xuancontains 761 works organized into 37 separate categories: Rhapsodies (fuPhú), Lyric Poetry (shīThi),Chu-style Elegies (sāoTao), Sevens (qīThất ), Edicts (zhàoChiếu ), Patents of Enfeoffment (cèSách ), Commands (lìngLệnh ), Instructions (jiàoGiáo ), Examination Prompts (cèwénSách văn ), Memorials (biǎoBiểu ), Letters of Submission (shàngshūThượng thư ), Communications (qǐKhải ), Memorials of Impeachment (tánshìĐạn sự ), Memoranda (jiānTiên ), Notes of Presentation (zòujìTấu ký ), Letters (shūThư ), Proclamations of War (xíHịch ), Responses to Questions (duìwènĐối vấn ), Hypothetical Discourses (shè lùnThiết luận ), Mixed song/rhapsody (cíTừ ), Prefaces (xùTự ), Praise Poems (sòngTụng ), Encomia for Famous Men (zànTán ), Prophetic Signs (fú mìngPhù mệnh ), Historical Treatises (shǐ lùnSử luận ), Historical Evaluations and Judgments (shǐ shù zànSử thuật tán ), Treatises (lùnLuận ), "Linked Pearls" (liánzhūLiên châu ), Admonitions (zhēnChâm ), Inscriptions (míngMinh ), Dirges (lěiLụy ), Laments (aīAi ), Epitaphs (béiBi ), Grave Memoirs (mùzhìMộ chí ), Conduct Descriptions (xíngzhuàngHành trạng ), Condolences (diàowénĐiếu văn ), and Offerings (jìTế ).[12]

The first group of categories – the "Rhapsodies" (fu) and "Lyric Poetry" (shi), and to a lesser extent the "Chu-style Elegies "and" Sevens "– are the largest and most important of theWen Xuan.[13]Its 55fu,in particular, are a "remarkably representative selection of major works",[13]and includes most of the greatestfumasterpieces, such asSima Xiangru's "Fuon the Excursion Hunt of the Emperor "(Tiānzǐ yóuliè fùThiên tử du liệp phú ),Yang Xiong's "Fuon the Sweet Springs Palace "(Gān Quán fùCam tuyền phú ),Ban Gu's "Fuon the Two Capitals "(Liǎng dū fùLưỡng đô phú ), andZhang Heng's "Fuon the Two Metropolises "(Èr jīng fùNhị kinh phú ).

Annotations

editThe first annotations to theWen Xuanappeared sixty to seventy years after its publication and were produced by Xiao Tong's cousin Xiao Gai.Cao Xian,Xu Yan,Li Shan,Gongsun Luo, and other scholars of the lateSui dynastyand Tang dynasty helped promote theWen Xuanuntil it became the focus of an entire branch of literature study: an early 7th century scholar fromYangzhounamed Cao Xian ( tào hiến ) produced a work entitledPronunciation and Meaning in theWen Xuan(Chinese:Văn tuyển âm nghĩa;pinyin:Wénxuǎn Yīnyì) and the others – who were his students – each produced their own annotations to the collection.

Li Shan commentary

editLi Shan ( lý thiện, d. 689) was a student of Cao Xian and a minor official who served on the staff ofLi Hong,a Crown Prince of the earlyTang dynasty.[14]Li had an encyclopedic knowledge of early Chinese language and literature which he used to create a detailed commentary to theWen Xuanthat he submitted to the imperial court ofEmperor Gaozong of Tangin 658, though he may have later expanded and revised it with the assistance of his son Li Yong ( lý ung ).[15]Li's annotations, which have been termed "models ofphilologicalrigor ", are some of the most exemplary in all of Chinese literature, giving accurate glosses of rare and difficult words and characters, as well as giving source information andloci classicifor notable passages.[16]His commentary is still the recognized as the most useful and important tool for reading and studying theWen Xuanin the original Chinese.[16]

"Five Officials" commentary

editIn 718, during the reign ofEmperor Xuanzong of Tang,a newWen Xuancommentary by court officials Lü Yanji, Liu Liang, Zhang Xian, Lü Xiang, and Li Zhouhan entitledCollected Commentaries of the Five Officials(Chinese:Ngũ thần tập chú;pinyin:Wǔchén jí zhù) was submitted to the imperial court.[17]This "Five Officials" commentary is longer and contains more paraphrases of difficult lines than Li Shan's annotations, but is also full of erroneous and far-fetched glosses and interpretations.[17]

Later editions

editBesides the Li Shan and "Five Officials" commentaries, a number of otherWen Xuaneditions seem to have circulated during theTang dynasty.Almost none of these other editions have survived to modern times, though a number of manuscripts have been preserved inJapan.A number of fragments of theWen Xuanor commentaries to it were rediscovered in Japan in the 1950s, including one fromDunhuangdiscovered in theEisei Bunko Museumand a complete manuscript of a shorterKujō( cửu điều,Mandarin:Jiǔtiáo) edition printed as early as 1099.[18]The best known of these other editions isCollected Commentaries of theWen Xuan (Wénxuǎn jízhùVăn tuyển tập chú,Japanese:Monzen shūchū), an edition of unknown authorship that contains some old Tang dynasty commentaries that were lost in China.[17]

Published during the reign ofEmperor Zhezong of Song,in the second lunar month of 1094, theYouzhou Prefecture Study Bookcontained the first compilation of the annotations of both the Five Officials and Li Shan. The laterAnnotations of the Six Scholarsedition (i.e. the Five Officials and Li Shan), such as Guang Dupei'swoodblockprinting and the Mingzhou printing was the most well-known edition of theYouzhoubook. Another edition, called theAnnotations of the Six Officials,which had Ganzhou and Jianzhou versions, was based on theSix Scholarsedition but altered the ordering of certain sections.

In the early 19th century, scholar Hu Kejia produced a collated and textually critical edition entitledKao Yi(Chinese:Khảo dị;lit.'A Study of the Differences'). This edition became the basis for most modern printings of theWen Xuan,such as theZhonghua Book Company's 1977 edition and the Shanghai Guji 1986 edition.

Influence

editBy the early 8th century theWen Xuanhad become an important text that all young men were expected to master in preparation for literary examinations.[17]Famed poetDu Fuadvised his son Du Zongwu to "master thoroughly the principles of theWen Xuan."[17]Copies of theWen Xuanwere obtained by nearly all families that could afford them in order to help their sons study the literary styles of the works it contained. This practice continued into theSong dynastyuntil theimperial examinationreforms of the late 11th century.[17]In the mid-16th century, during theMing dynasty,an abridged version of theWen Xuanwas created to help aspiring officials study composition for theeight-legged essayson Ming-era imperial exams.[19]

Influence in Japan

editTheWen Xuan(Japanese:Mon-zen) was transmitted to Japan sometime after its initial publication and had become required reading for the Japanese aristocracy by theHeian period.Admired for its beauty, many terms from theWen Xuanmade their way intoJapaneseasloanwordsand are still used.

Translations

editFrench

edit- Margouliès, Georges (1926),Le "Fou" dans le Wen siuan: Étude et textes,Paris: Paul Geuthner.

German

edit- von Zach, Erwin(1958), Fang, Ilse Martin (ed.),Die Chinesische Anthologie: Übersetzungen aus dem Wen Hsüan,Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard-Yenching Studies, Harvard University Press.

Japanese

edit- Uchida, Sennosuke nội điền tuyền chi trợ; Ami, Yuji võng hữu thứ (1963–64),Monzen: ShihenVăn tuyển: Thi thiên, 2 vols.,Tokyo: Meiji shoin.

- Obi, Kōichi tiểu vĩ giao nhất; Hanabusa, Hideki hoa phòng anh thụ (1974–76),MonzenVăn tuyển, 7 vols.,Tokyo: Shūeisha.

- Nakajima, Chiaki trung đảo thiên thu (1977),Monzen: FuhenVăn tuyển: Phú thiên,Tokyo: Meiji shoin.

English

edit- Knechtges, David R.(1982),Wen Xuanor Selections of Refined Literature, Volume 1: Rhapsodies on Metropolises and Capitals,Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ———— (1987),Wen Xuanor Selections of Refined Literature, Volume 2: Rhapsodies on Sacrifices, Hunting, Travel, Sightseeing, Palaces and Halls, Rivers and Seas,Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ———— (1996),Wen Xuanor Selections of Refined Literature, Volume 3: Rhapsodies on Natural Phenomena, Birds and Animals, Aspirations and Feelings, Sorrowful Laments, Literature, Music, and Passions,Princeton: Princeton University Press.

References

editFootnotes

edit- ^Idema & Haft (1997),p. 112.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 1.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 4.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 5.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 19.

- ^Knechtges (2015),p. 382.

- ^Idema and Haft (1997): 112.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 32.

- ^Knechtges (2014),p. 1323.

- ^Knechtges (2014),p. 1328.

- ^Knechtges (2014),p. 1324.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 21-22; some translations given as updated in Knechtges (1995): 42.

- ^abKnechtges (1982): 28.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 52.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 52-53.

- ^abKnechtges (1982): 53.

- ^abcdefKnechtges (1982): 54.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 64.

- ^Knechtges (1982): 57.

Works cited

edit- Idema, Wilt; Haft, Lloyd (1997).A Guide to Chinese Literature.Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan.ISBN0-89264-123-1.

- Knechtges, David R.(1982).Wen Xuanor Selections of Refined Literature, Volume 1: Rhapsodies on Metropolises and Capitals.Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ——— (1995). "Problems of Translation". In Eoyang, Eugene; Lin, Yaofu (eds.).Translating Chinese Literature.Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 41–56.ISBN0-253-31958-7.

- ——— (2014). "Wen XuanVăn tuyển(Selections of Refined Literature)".In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.).Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part Two.Leiden: Brill. pp. 1313–48.ISBN978-90-04-19240-9.

- ——— (2015). "Wen XuanVăn tuyển ". In Chennault, Cynthia L.; Knapp, Keith N.; Berkowitz, Alan J.; Dien, Albert E. (eds.).Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Bibliographical Guide.Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 381–88.ISBN978-1-55729-109-7.

- Owen, Stephen, ed. (2010).The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 1.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.