This article includes a list ofgeneral references,butit lacks sufficient correspondinginline citations.(April 2009) |

Atlantic herring(Clupea harengus) is aherringin thefamilyClupeidae.It is one of the most abundant fish species in the world. Atlantic herrings can be found on both sides of theAtlantic Ocean,congregating in largeschools.They can grow up to 45 centimetres (18 in) in length and weigh up to 1.1 kilograms (2.4 lb). They feed oncopepods,krilland small fish, while their natural predators areseals,whales,codand other larger fish.

| Atlantic herring | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Clupeiformes |

| Family: | Clupeidae |

| Genus: | Clupea |

| Species: | C. harengus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Clupea harengus | |

| |

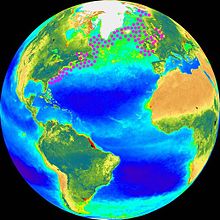

| Distribution on aNASASeaWIFSimage | |

The Atlantic herringfisheryhas long been an important part of the economy ofNew Englandand theAtlantic provincesof Canada. This is because the fish congregate relatively near to the coast in massive schools, notably in the cold waters of the semi-enclosedGulf of MaineandGulf of St. Lawrence.North Atlantic herring schools have been measured up to 4 cubic kilometres (0.96 cu mi) in size, containing an estimated four billion fish.

Description

editAtlantic herring have afusiformbody.Gill rakersin their mouths filter incoming water, trapping anyzooplanktonandphytoplankton.

Atlantic herring are in general fragile. They have large and delicategillsurfaces, and contact with foreign matter can strip away their large scales.

They have retreated from manyestuariesworldwide due to excess waterpollutionalthough in some estuaries that have been cleaned up, herring have returned. The presence of theirlarvaeindicates cleaner and more–oxygenated waters.

Range and habitat

editAtlantic herring can be found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. They range,shoaling and schooling,across North Atlantic waters such as theGulf of Maine,theGulf of St Lawrence,theBay of Fundy,theLabrador Sea,theDavis Straits,theBeaufort Sea,theDenmark Strait,theNorwegian Sea,theNorth Sea,theSkagerrak,theEnglish Channel,theCeltic Sea,theIrish Sea,theBay of BiscayandSea of the Hebrides.[2]Although Atlantic herring are found in the northern waters surrounding theArctic,they are not considered to be an Arctic species.

Baltic herring

editThe small-sized herring in the inner parts of theBaltic Sea,which is also less fatty than the true Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus harengus), is considered a distinct subspecies,"Baltic herring"(Clupea harengus membras), despite the lack of a distinctivegenome.The Baltic herring has a specific name in many local languages (Swedishströmming,Finnishsilakka,Estonianräim,silk,Livoniansiļk,Russian салака, Polishśledź bałtycki,Latvianreņģes,Lithuanian strimelė) and is popularly and in cuisine considered distinct from herring. For example, the Swedish dishsurströmmingis made from Baltic herring.

Fisheries for Baltic herring have been at unsustainable levels since theMiddle Ages.Around this time, the primary Baltic herring catch consisted of anautumn-spawning population. Cooling in the mid-16th century related to theLittle Ice Age,combined with thisoverfishing,led to a dramatic loss of productivity in the population of autumn-spawning herring that rendered it nearly extinct. Due to this, the autumn-spawning herring were largely replaced by aspring-spawning population, which has since comprised most of the Baltic herring fisheries; this population is also at risk of overfishing.[3]

Life cycle

editHerrings reach sexual maturity when they are 3 to 5 years old. The life expectancy once mature is 12 to 16 years. Atlantic herring may have different spawning components within a single stock which spawn during different seasons. They spawn in estuaries, coastal waters or in offshore banks. Fertilization is external, as in most other fish: the female releases between 20,000 and 40,000 eggs and the males simultaneously release masses of milt so that they mix freely in the sea. Once fertilized the 1 to 1.4 mm diameter eggs sink to the sea bed where their sticky surface adheres to gravel or weed. They mature in 1–3 weeks; in 14–19 °C water it takes 6–8 days, in 7,5 °C it takes 17 days.[4]They will only mature if the water temperature stays below 19 °C.[citation needed]The hatched larvae are 3 to 4 mm long and transparent except for the eyes which have some pigmentation.[5]

Population

editHerrings are most seen in the North Atlantic Ocean, from the coast ofSouth Carolinauntil Greenland, and from the Baltic Sea untilNovaya Zemlya.In theNorth Seapeople can distinguish four different main populations spawning in different periods:[citation needed]

- The Buchan-Shetland herrings spawn in August and September near the Scottish andShetlandcoasts.

- On theDogger Bankherrings spawn from August until October.

- The more southern population will spawn later, from November until January. These are the herrings from the Southern Bight of Downs.

- TheSoused herringspawns every spring in the Baltic Sea, and travels via Skagerrak to the North Sea.

These four populations live outside of the spawn season interchangeably. In their spawn season, each population gathers together on their own spawn grounds.[citation needed]

In the past, there was another, fifth distinct population, theZuiderzeeherring, which spawned in the former Zuiderzee. This population disappeared when the Zuiderzee was drained by the Dutch as part of the largerZuiderzee Works.[citation needed]

Ecology

editHerring-like fish are the most important fish group on the planet. They are also the most populous fish.[6]They are the dominant converter ofzooplanktoninto fish, consumingcopepods,arrow wormschaetognatha,pelagic amphipodshyperiidae,mysidsandkrillin thepelagic zone.Conversely, they are a central prey item orforage fishfor highertrophic levels.The reasons for this success are still Enigma tic; one speculation attributes their dominance to the huge, extremely fast cruisingschoolsthey inhabit.

Orca,cod,dolphins,porpoises,sharks,rockfish,seabirds,whales,squid,sea lions,seals,tuna,salmon,andfishermenare among the predators of these fishes.

Herring's pelagic–prey includescopepods(e.g.Centropagidae,Calanusspp.,Acartiaspp.,Temoraspp.),amphipodslikeHyperiaspp., larvalsnails,diatomsby larvae below 20 millimetres (0.79 in), peridinians,molluscanlarvae, fish eggs,krilllikeMeganyctiphanes norvegica,mysids,small fishes,menhadenlarvae,pteropods,annelids,tintinnidsby larvae below 45 millimetres (1.8 in), Haplosphaera,Pseudocalanus.

Schooling

editAtlantic herring canschoolin immense numbers. Radakov estimated herring schools in the North Atlantic can occupy up to 4.8 cubic kilometres with fish densities between 0.5 and 1.0 fish/cubic metre, equivalent to several million fish in one school.[7]

Herring are amongst the most spectacular schoolers ( "obligate schoolers" under older terminology). They aggregate in groups that consist of thousands to hundreds of thousands or even millions of individuals. The schools traverse the open oceans.

Schools have a very precise spatial arrangement that allows the school to maintain a relatively constant cruising speed. Schools from an individual stock generally travel in a triangular pattern between their spawning grounds, e.g. SouthernNorway,their feeding grounds (Iceland) and their nursery grounds (Northern Norway). Such wide triangular journeys are probably important because feeding herrings cannot distinguish their own offspring. They have excellent hearing, and a school can react very quickly to evade predators. Herring schools keep a certain distance from a moving scuba diver or a cruising predator like a killer whale, forming a vacuole which looks like a doughnut from a spotter plane.[8]The phenomenon of schooling is far from understood, especially the implications on swimming and feeding-energetics. Many hypotheses have been put forward to explain the function of schooling, such as predator confusion, reduced risk of being found, better orientation, andsynchronizedhunting. However, schooling has disadvantages such as: oxygen- and food-depletion and excretion buildup in the breathing media. The school-array probably gives advantages in energy saving although this is a highly controversial and much debated field.

Schools of herring can on calm days sometimes be detected at the surface from more than a mile away by the little waves they form, or from a few meters at night when they triggerbioluminescencein surroundingplankton( "firing" ). All underwater recordings show herring constantly cruising reaching speeds up to 108 centimetres (43 in) per second, and much higher escape speeds.

Relationship with humans

editFisheries

editThe Atlantic herring fishery is managed by multiple organizations that work together on the rules and regulations applying to herring. As of 2010 the species was not threatened byoverfishing.[10]

They are an important bait fish for recreational fishermen.[11]

-

Purse seiningfor Atlantic herring

-

Harvesting with the purse seine

-

The catch

Aquariums

editBecause of their feeding habits, cruising desire, collective behavior and fragility they survive in very fewaquariaworldwide despite their abundance in the ocean. Even the best facilities leave them slim and slow compared to healthy wild schools.

Notes

edit- ^Herdson, D.; Priede, I.G. (2010)."Clupea harengus".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2010:e.T155123A4717767.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T155123A4717767.en.Retrieved2 July2023.

- ^C.Michael Hogan, (2011)Sea of the HebridesArchived24 May 2013 at theWayback Machine.Eds. P.Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC.

- ^University, Kiel."Climatic changes and overfishing depleted Baltic herring long before industrialisation".phys.org.Retrieved3 December2021.

- ^"Sill".Fiskbasen(in Swedish).Retrieved19 July2018.

- ^Bora, Chandramita (25 August 2016)."Really Striking Facts About Herring Fish".Buzzle.Archived from the original on 16 May 2017.

{{cite news}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^Guinness Book of Records

- ^Radakov DV (1973)Schooling in the ecology of fish.Israel Program for Scientific Translation, translated by Mill H. Halsted Press, New York.ISBN978-0-7065-1351-6

- ^Nøttestad, L.; Axelsen, B. E. (1999)."Herring schooling manoeuvres in response to killer whale attacks"(PDF).Canadian Journal of Zoology.77(10): 1540–1546.doi:10.1139/z99-124.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 17 December 2008.Retrieved30 July2012.

- ^Clupea harengus(Linnaeus, 1758)FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- ^"Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission: Atlantic Herring".Archived fromthe originalon 27 April 2004.Retrieved2 July2009.

- ^Daniello, Capt. Vincent (13 May 2019)."A Guide to Saltwater Live Baits".sportfishingmag.Sport Fishing Magazine.Retrieved21 June2019.

Other references

edit- "Clupea harengus".Integrated Taxonomic Information System.Retrieved11 March2006.

- Kils, U.,The ecoSCOPE and dynIMAGE: Microscale Tools forin situStudies of Predator Prey InteractionsArchived21 February 2008 at theWayback Machine.Arch Hydrobiol Beih 36:83-96;1992

- NOAA Fisheries (22 June 2023)."Species Directory: Atlantic Herring".NOAA Fisheries.Retrieved29 June2023.

Further reading

edit- Bigelow, H.B., M.G. Bradbury, J.R. Dymond, J.R. Greeley, S.F. Hildebrand, G.W. Mead, R.R. Miller, L.R. Rivas, W.L. Schroeder, R.D. Suttkus and V.D. Vladykov (1963)Fishes of the western North Atlantic. Part threeNew Haven, Sears Found. Mar. Res., Yale Univ.

- Eschmeyer, William N., ed. 1998Catalog of FishesSpecial Publication of the Center for Biodiversity Research and Information, no. 1, vol 1–3. California Academy of Sciences. San Francisco, California, USA. 2905.ISBN0-940228-47-5.

- Fish, M.P. and W.H. Mowbray (1970)Sounds of Western North Atlantic fishes. A reference file of biological underwater soundsThe Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore.

- Flower, S.S. (1935)Further notes on the duration of life in animals. I. Fishes: as determined by otolith and scale-readings and direct observations on living individualsProc. Zool. Soc. London 2:265-304.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (1992). FAO yearbook 1990.Fishery statistics. Catches and landingsFAO Fish. Ser. (38). FAO Stat. Ser. 70:(105):647 p.

- Joensen, J.S. and Å. Vedel Tåning (1970)Marine and freshwater fishes. Zoology of the Faroes LXII - LXIII,241 p. Reprinted from,

- Jonsson, G. (1992). Islenskir fiskar. Fiolvi, Reykjavik, 568 pp.

- Kinzer, J. (1983)Aquarium Kiel: Beschreibungen zur Biologie der ausgestellten Tierarten.Institut für Meereskunde an der Universität Kiel. pag. var.

- Koli, L. (1990)Suomen kalat. [Fishes of Finland]Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. Helsinki. 357 p. (in Finnish).

- Laffaille, P., E. Feunteun and J.C. Lefeuvre (2000)Composition of fish communities in a European macrotidal salt marsh (the Mont Saint-Michel Bay, France)Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 51(4):429-438.

- Landbrugs -og Fiskeriministeriet. (1995). Fiskeriårbogen 1996Årbog for den danske fiskerflådeFiskeriårbogens Forlag ved Iver C. Weilbach & Co A/S, Toldbodgade 35, Postbox 1560, DK-1253 København K, Denmark. p 333–338, 388, 389 (in Danish).

- Linnaeus, C. (1758)Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae secundum Classes, Ordinus, Genera, Species cum Characteribus, Differentiis Synonymis, Locis10th ed., Vol. 1. Holmiae Salvii. 824 p.

- Munroe, Thomas, A. / Collette, Bruce B., and Grace Klein-MacPhee, eds. 2002Herrings: Family Clupeidae. Bigelow and Schroeder's Fishes of the Gulf of Maine,Third Edition. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, DC, USA. 111–160.ISBN1-56098-951-3.

- Murdy, Edward O., Ray S. Birdsong, and John A. Musick 1997Fishes of Chesapeake BaySmithsonian Institution Press. Washington, DC, USA. xi + 324.ISBN1-56098-638-7.

- Muus, B., F. Salomonsen and C. Vibe (1990)Grønlands fauna (Fisk, Fugle, Pattedyr)Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag A/S København, 464 p. (in Danish).

- Muus, B.J. and J.G. Nielsen (1999)Sea fish. Scandinavian Fishing Year BookHedehusene, Denmark. 340 p.

- Muus, B.J. and P. Dahlström (1974)Collins guide to the sea fishes of Britain and North-Western EuropeCollins, London, UK. 244 p.

- Reid RN, Cargnelli LM, Griesbach SJ, Packer DB, Johnson DL, Zetlin CA, Morse WW, Berrien PL (1999).Atlantic Herring,Clupea harengus,Life History and Habitat Characteristics(PDF)(Report). Woods Hole, Massachusetts: Northeast Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-126, NOAA. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 13 February 2017.

- Robins, Richard C.,Reeve M. Bailey,Carl E. Bond, James R. Brooker, Ernest A. Lachner, et al. 1991Common and Scientific Names of Fishes from the United States and Canada,Fifth Edition. American Fisheries Society Special Publication, no. 20. American Fisheries Society. Bethesda, Maryland, USA. 183.ISBN0-913235-70-9.

- Whitehead, Peter J. P. 1985.Clupeoid Fishes of the World (Suborder Clupeoidei): An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of the Herrings, Sardines, Pilchards, Sprats, Shads, Anchovies and Wolf-herrings: Part 1 - Chirocentridae, Clupeidae and PristigasteridaeFAO Fisheries Synopsis, no. 125, vol. 7, pt. 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. x + 303.ISBN92-5-102340-9.

External links

edit- Information on Fishbase

- Information on clupea.de

- Atlantic herring(Clupea harengus) pages on Gulf of Maine Research Institute