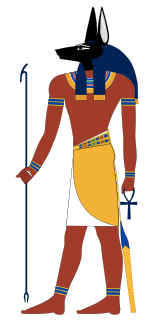

Anubis(/əˈnjuːbɪs/;[2]Ancient Greek:Ἄνουβις), also known asInpu,Inpw,Jnpw,orAnpuinAncient Egyptian(Coptic:ⲁⲛⲟⲩⲡ,romanized:Anoup), is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to theunderworld,inancient Egyptian religion,usually depicted as acanineor a man with acanine head.[3]

| Anubis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Name inhieroglyphs | ||||||

| Major cult center | Lycopolis,Cynopolis | |||||

| Symbol | Mummy gauze,fetish,jackal,flail | |||||

| Genealogy | ||||||

| Parents | SetandNepthys,Osiris(Middle and New kingdom),orRa(Old kingdom). | |||||

| Siblings | Wepwawet | |||||

| Consort | Anput,Nephthys[1] | |||||

| Offspring | Kebechet | |||||

| Equivalents | ||||||

| Greek equivalent | HadesorHermes | |||||

Like manyancient Egyptian deities,Anubis assumed different roles in various contexts. Depicted as a protector of graves as early as theFirst Dynasty(c. 3100– c. 2890 BC), Anubis was also anembalmer.By theMiddle Kingdom(c. 2055–1650 BC) he was replaced byOsirisin his role as lord of theunderworld.One of his prominent roles was as agod who ushered souls into the afterlife.He attended theweighing scaleduring the "Weighing of the Heart", in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. Anubis is one of the most frequently depicted and mentioned gods in theEgyptian pantheon;however, no relevant myth involved him.[4]

Anubis was depicted in black, a color that symbolized regeneration, life, the soil of theNile River,and the discoloration of the corpse after embalming. Anubis is associated with his brotherWepwawet,another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog's head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.[5]Anubis' female counterpart isAnput.His daughter is the serpent goddessKebechet.

Name

"Anubis" is a Greek rendering of this god'sEgyptianname.[6][7]Before theGreeks arrived in Egypt,around the 7th century BC, the god was known asAnpuorInpu.The root of the name in ancient Egyptian language means "a royal child."Inpuhas a root to "inp", which means "to decay." The god was also known as "First of the Westerners," "Lord of the Sacred Land," "He Who is Upon his Sacred Mountain," "Ruler of the Nine Bows," "The Dog who Swallows Millions," "Master of Secrets," "He Who is in the Place of Embalming," and "Foremost of the Divine Booth."[8]The positions that he had were also reflected in the titles he held such as "He Who Is upon His Mountain," "Lord of the Sacred Land," "Foremost of the Westerners," and "He Who Is in the Place of Embalming."[9]

In theOld Kingdom(c. 2686 BC– c. 2181 BC), the standard way of writing his name inhieroglyphswas composed of the sound signsinpwfollowed by a jackal[a]over aḥtpsign:[11]

A new form with the jackal on a tall stand appeared in the late Old Kingdom and became common thereafter:[11]

Anubis' namejnpwwas possibly pronounced[aˈna.pʰa(w)],based on CopticAnoupand theAkkadiantranscription⟨a-na-pa⟩(𒀀𒈾𒉺) in the name <ri-a-na-pa> "Reanapa"that appears inAmarna letterEA 315.[12][13]However, this transcription may also be interpreted asrˁ-nfr,a name similar to that of PrinceRaneferof theFourth Dynasty.

History

In Egypt'sEarly Dynastic period(c. 3100– c. 2686 BC), Anubis was portrayed in full animal form, with a "jackal"head and body.[14]A jackal god, probably Anubis, is depicted in stone inscriptions from the reigns ofHor-Aha,Djer,and other pharaohs of theFirst Dynasty.[15]SincePredynastic Egypt,when the dead were buried in shallow graves, jackals had been strongly associated with cemeteries because they were scavengers which uncovered human bodies and ate their flesh.[16]In the spirit of "fighting like with like," a jackal was chosen to protect the dead, because "a common problem (and cause of concern) must have been the digging up of bodies, shortly after burial, by jackals and other wild dogs which lived on the margins of the cultivation."[17]

In theOld Kingdom,Anubis was the most important god of the dead. He was replaced in that role by Osiris during theMiddle Kingdom(2000–1700 BC).[18]In theRoman era,which started in 30 BC, tomb paintings depict him holding the hand of deceased persons to guide them to Osiris.[19]

The parentage of Anubis varied between myths, times and sources. In early mythology, he was portrayed as a son ofRa.[20]In theCoffin Texts,which were written in theFirst Intermediate Period(c. 2181–2055 BC), Anubis is the son of either the cow goddessHesator the cat-headedBastet.[21]Another tradition depicted him as the son of Ra andNephthys.[20]The GreekPlutarch(c. 40–120 AD) reported a tradition that Anubis was the illegitimate son of Nephthys and Osiris, but that he was adopted by Osiris's wifeIsis:[22]

For when Isis found out that Osiris loved her sister and had relations with her in mistaking her sister for herself, and when she saw a proof of it in the form of a garland of clover that he had left to Nephthys – she was looking for a baby, because Nephthys abandoned it at once after it had been born for fear ofSet;and when Isis found the baby helped by the dogs which with great difficulties lead her there, she raised him and he became her guard and ally by the name of Anubis.

George Hartsees this story as an "attempt to incorporate the independent deity Anubis into theOsirian pantheon."[21]An Egyptian papyrus from theRoman period(30–380 AD) simply called Anubis the "son of Isis."[21]InNubia,Anubis was seen as the husband of his mother Nephthys.[1]

In thePtolemaicperiod (350–30 BC), when Egypt became aHellenistickingdom ruled by Greek pharaohs, Anubis was merged with theGreekgodHermes,becomingHermanubis.[23][24]The two gods were considered similar because they bothguided soulsto the afterlife.[25]The center of thiscultwas inuten-ha/Sa-ka/Cynopolis,a place whose Greek name means "city of dogs." In Book XI ofThe Golden AssbyApuleius,there is evidence that the worship of this god was continued inRomethrough at least the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in thealchemicalandhermeticalliterature of theMiddle Agesand theRenaissance.

Although the Greeks andRomanstypically scorned Egyptian animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was mockingly called "Barker" by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated withSiriusin the heavens andCerberusand Hades in the underworld.[26]In his dialogues,Platooften hasSocratesutter oaths "by the dog" (Greek:kai me ton kuna), "by the dog of Egypt", and "by the dog, the god of the Egyptians", both for emphasis and to appeal to Anubis as an arbiter of truth in the underworld.[27]

Roles

Embalmer

Asjmy-wt(Imiut or theImiut fetish) "He who is in the place ofembalming",Anubis was associated withmummification.He was also calledḫnty zḥ-nṯr"He who presides over the god's booth", in which "booth" could refer either to the place where embalming was carried out or the pharaoh's burial chamber.[28][29]

In theOsiris myth,Anubis helped Isis to embalm Osiris.[18]Indeed, when the Osiris myth emerged, it was said that after Osiris had been killed by Set, Osiris's organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers; during the rites of mummification, illustrations from theBook of the Deadoften show a wolf-mask-wearing priest supporting the upright mummy.

Protector of tombs

Anubis was a protector ofgravesandcemeteries.Several epithets attached to his name inEgyptian texts and inscriptionsreferred to that role.Khenty-Amentiu,which means "foremost of the westerners" and was also the name of a differentcanine funerary god,alluded to his protecting function because the dead were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile.[30]He took other names in connection with his funerary role, such astpy-ḏw.f(Tepy-djuef) "He who is upon his mountain" (i.e. keeping guard over tombs from above) andnb-t3-ḏsr(Neb-ta-djeser) "Lord of the sacred land", which designates him as a god of the desertnecropolis.[28][29]

TheJumilhac papyrusrecounts another tale where Anubis protected the body of Osiris from Set. Set attempted to attack the body of Osiris by transforming himself into aleopard.Anubis stopped and subdued Set, however, and hebrandedSet's skin with a hot iron rod. Anubis thenflayedSet and wore his skin as a warning against evil-doers who would desecrate thetombs of the dead.[31]Priests who attended to the dead wore leopard skin in order to commemorate Anubis' victory over Set. The legend of Anubis branding the hide of Set in leopard form was used to explain how the leopard got its spots.[32]

Most ancient tombs had prayers to Anubis carved on them.[33]

Guide of souls

By thelate pharaonic era(664–332 BC), Anubis was often depicted as guiding individuals across the threshold from the world of the living to theafterlife.[34]Though a similar role was sometimes performed by the cow-headedHathor,Anubis was more commonly chosen to fulfill that function.[35]Greek writers from theRoman periodof Egyptian history designated that role as that of "psychopomp",a Greek term meaning" guide of souls "that they used to refer to their own godHermes,who also played that role inGreek religion.[25]Funerary artfrom that period represents Anubis guiding either men or women dressed in Greek clothes into the presence of Osiris, who by then had long replaced Anubis as ruler of the underworld.[36]

Weigher of hearts

One of the roles of Anubis was as the "Guardian of the Scales."[37]The critical scene depicting the weighing of the heart, in theBook of the Dead,shows Anubis performing a measurement that determined whether the person was worthy of entering the realm of the dead (theunderworld,known asDuat). By weighing the heart of a deceased person againstma'at,who was often represented as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. Souls heavier than a feather would be devoured byAmmit,and souls lighter than a feather would ascend to a heavenly existence.[38][39]

Portrayal in art

Anubis was one of the most frequently represented deities inancient Egyptian art.[4]He is depicted in royal tombs as early as theFirst Dynasty.[8]The god is typically treating a king's corpse, providing sovereign to mummification rituals and funerals, or standing with fellow gods at theWeighing of the Heart of the Soulin the Hall of Two Truths.[9]One of his most popular representations is of him, with the body of a man and the head of a jackal with pointed ears, standing or kneeling, holding a gold scale while a heart of the soul is being weighed against Ma'at's white truth feather.[8]

In theearly dynastic period,he was depicted in animal form, as a black canine.[40]Anubis's distinctive black color did not represent the animal, rather it had several symbolic meanings.[41]It represented "the discolouration of the corpse after its treatment withnatronand the smearing of the wrappings with a resinous substance during mummification. "[41]Being the color of the fertilesiltof theRiver Nile,to Egyptians, black also symbolized fertility and the possibility of rebirth in the afterlife.[42]In theMiddle Kingdom,Anubis was often portrayed as a man with the head of a jackal.[43]TheAfrican jackalwas the species depicted and the template of numerous Ancient Egyptian deities, including Anubis.[44]An extremely rare depiction of him infully human formwas found in a chapel ofRamesses IIinAbydos.[41][7]

Anubis is often depicted wearing a ribbon and holding anḫ3ḫ3"flail"in the crook of his arm.[43]Another of Anubis's attributes was thejmy-wtorimiut fetish,named for his role in embalming.[45]In funerary contexts, Anubis is shown either attending to a deceased person's mummy or sitting atop a tomb protecting it.New Kingdomtomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop thenine bowsthat symbolize his domination over the enemies of Egypt.[46]

-

Statue of Anubis

-

Wall relief of Anubis in (KV17) the tomb of Seti I, 19th Dynasty, Valley of the Kings

-

Anubis receiving offerings,hieroglyphname in third column from left, 14th century BC; painted limestone; fromSaqqara(Egypt)

-

TheAnubis Shrine;1336–1327 BC; painted wood and gold; 1.1 × 2.7 × 0.52 m; from theValley of the Kings;Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

Stela of Siamun and Taruy worshipping Anubis

-

The king with Anubis, from thetomb of Horemheb;1323-1295 BC; tempera on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Anubis amulet; 664–30 BC; faience; height: 4.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Recumbent Anubis; 664–30 BC; limestone, originally painted black; height: 38.1 cm, length: 64 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Statuette of Anubis; 332–30 BC; plastered and painted wood; 42.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Worship

Although he does not appear in many myths, he was extremely popular with Egyptians and those of other cultures.[8]TheGreekslinked him to their god Hermes, the god who guided the dead to the afterlife. The pairing was later known asHermanubis.Anubis was heavily worshipped because, despite modern beliefs, he gave the people hope. People marveled in the guarantee that their body would be respected at death, their soul would be protected and justly judged.[8]

Anubis had male priests who sported wood masks with the god's likeness when performing rituals.[8][9]His cult center was atCynopolisinUpper Egyptbut memorials were built everywhere and he was universally revered in every part of the nation.[8]

See also

References

Informational notes

- ^The wild canine species in Egypt, long thought to have been a geographical variant of thegolden jackalin older texts, was reclassified in 2015 as a separate species known as theAfrican wolf,which was found to be more closely related towolvesandcoyotesthan to the jackal.[10]Nevertheless, ancient Greek texts about Anubis constantly refer to the deity as having a dog's head, not a jackal or wolf's, and there is still uncertainty as to what canid represents Anubis. Therefore the Name and History section uses the names the original sources used but in quotation marks.

Citations

- ^abLévai, Jessica (2007).Aspects of the Goddess Nephthys, Especially During the Graeco-Roman Period in Egypt.UMI.Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2023.Retrieved15 November2021.

- ^Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition.Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 56

- ^Turner, Alice K. (1993).The History of Hell(1st ed.). United States:Harcourt Brace.p. 13.ISBN978-0-15-140934-1.

- ^abJohnston 2004,p. 579.

- ^Gryglewski 2002,p. 145.

- ^Coulter & Turner 2000,p. 58.

- ^ab"Gods and Religion in Ancient Egypt – Anubis".Archived fromthe originalon 27 December 2002.Retrieved23 June2012.

- ^abcdefg"Anubis".World History Encyclopedia.Archivedfrom the original on 20 May 2023.Retrieved18 November2018.

- ^abc"Anubis".Encyclopaedia Britannica.2018.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2019.Retrieved3 December2018.

- ^Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Johnson, Warren E.; o'Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015)."Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species".Current Biology.25(#16): 2158–65.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060.PMID26234211.

- ^abLeprohon 1990,p. 164, citingFischer 1968,p. 84 andLapp 1986,pp. 8–9.

- ^Conder 1894,p.85.

- ^"CDLI-Archival View".cdli.ucla.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 21 September 2017.Retrieved20 September2017.

- ^Wilkinson 1999,p. 262.

- ^Wilkinson 1999,pp. 280–81.

- ^Wilkinson 1999,p. 262 (burials in shallow graves in Predynastic Egypt);Freeman 1997,p. 91 (rest of the information).

- ^Wilkinson 1999,p. 262 ( "fighting like with like" and "by jackals and other wild dogs" ).

- ^abFreeman 1997,p. 91.

- ^Riggs 2005,pp. 166–67.

- ^abHart 1986,p. 25.

- ^abcHart 1986,p. 26.

- ^Gryglewski 2002,p. 146.

- ^Peacock 2000,pp. 437–38 (Hellenistic kingdom).

- ^"Hermanubis | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon".Babylon. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved15 June2012.

- ^abRiggs 2005,p. 166.

- ^Hoerber 1963,p. 269 (for Cerberus and Hades).

- ^E.g.,Gorgias,482b (Blackwood, Crossett & Long 1962,p. 318), orThe Republic,399e, 567e, 592a (Hoerber 1963,p. 268).

- ^abHart 1986,pp. 23–24;Wilkinson 2003,pp. 188–90.

- ^abVischak, Deborah (27 October 2014).Community and Identity in Ancient Egypt: The Old Kingdom Cemetery at Qubbet el-Hawa.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9781107027602.

- ^Hart 1986,p. 23.

- ^Armour 2001.

- ^Zandee 1960,p. 255.

- ^"The Gods of Ancient Egypt – Anubis".touregypt.net.Archivedfrom the original on 7 September 2018.Retrieved29 June2014.

- ^Kinsley 1989,p. 178;Riggs 2005,p. 166 ( "The motif of Anubis, or less frequently Hathor, leading the deceased to the afterlife was well-established in Egyptian art and thought by the end of the pharaonic era." ).

- ^Riggs 2005,pp. 127 and 166.

- ^Riggs 2005,pp. 127–28 and 166–67.

- ^Faulkner, Andrews & Wasserman 2008,p.155.

- ^"Museum Explorer / Death in Ancient Egypt – Weighing the heart".British Museum.Archivedfrom the original on 11 October 2015.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"Gods of Ancient Egypt: Anubis".Britishmuseum.org.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2015.Retrieved15 June2012.

- ^Wilkinson 1999,p. 263.

- ^abcHart 1986,p. 22.

- ^Hart 1986,p. 22;Freeman 1997,p. 91.

- ^ab"Ancient Egypt: the Mythology – Anubis".Egyptianmyths.net.Archivedfrom the original on 17 December 2018.Retrieved15 June2012.

- ^Remler, P. (2010).Egyptian Mythology, A to Z.Infobase Publishing. p. 99.ISBN978-1438131801.

- ^Wilkinson 1999,p. 281.

- ^Wilkinson 2003,pp. 188–90.

- ^Campbell, Price (2018).Ancient Egypt - Pocket Museum.Thames & Hudson. p. 266.ISBN978-0-500-51984-4.

Bibliography

- Armour, Robert A. (2001),Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt,Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press

- Blackwood, Russell; Crossett, John; Long, Herbert (1962), "Gorgias 482b",The Classical Journal,57(7): 318–19,JSTOR3295283.

- Conder, Claude Reignier (trans.)(1894) [1893],The Tell Amarna Tablets(Second ed.), London: Published for the Committee of thePalestine Exploration Fundby A.P. Watt,ISBN978-1-4147-0156-1.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000),Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities,Jefferson (NC) and London: McFarland,ISBN978-0-7864-0317-2.

- Faulkner, Raymond O.; Andrews, Carol; Wasserman, James (2008),The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day,Chronicle Books,ISBN978-0-8118-6489-3.

- Fischer, Henry George (1968),Dendera in the Third Millennium B. C., Down to the Theban Domination of Upper Egypt,London: J.J. Augustin.

- Freeman, Charles (1997),The Legacy of Ancient Egypt,New York: Facts on File,ISBN978-0-816-03656-1.

- Gryglewski, Ryszard W. (2002),"Medical and Religious Aspects of Mummification in Ancient Egypt"(PDF),Organon,31(31): 128–48,PMID15017968,archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Hart, George (1986),A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses,London: Routledge & Kegan Paul,ISBN978-0-415-34495-1.

- Hoerber, Robert G. (1963), "The Socratic Oath 'By the Dog'",The Classical Journal,58(6): 268–69,JSTOR3293989.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles (general ed.) (2004),Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide,Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press,ISBN978-0-674-01517-3.

- Kinsley, David (1989),The Goddesses' Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West,Albany (NY):State University of New YorkPress,ISBN978-0-88706-835-5.(paperback).

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lapp, Günther (1986),Die Opferformel des Alten Reiches: unter Berücksichtigung einiger späterer Formen[The offering formula of the Old Kingdom: considering a few later forms], Mainz am Rhein: Zabern,ISBN978-3805308724.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (1990), "The Offering Formula in the First Intermediate Period",The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology,76:163–64,doi:10.1177/030751339007600115,JSTOR3822017,S2CID192258122.

- Peacock, David (2000),"The Roman Period",inShaw, Ian(ed.),The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt,Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0-19-815034-3.

- Riggs, Christina(2005),The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion,Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003),The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt,London: Thames & Hudson,ISBN978-0-500-05120-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999),Early Dynastic Egypt,London: Routledge

- Zandee, Jan (1960),Death as an Enemy: According to Ancient Egyptian Conceptions,Brill Archive, GGKEY:A7N6PJCAF5Q

Further reading

- Duquesne, Terence (2005).The Jackal Divinities of Egypt I.Darengo Publications.ISBN978-1-871266-24-5.

- El-Sadeek, Wafaa; Abdel Razek, Sabah (2007).Anubis, Upwawet, and Other Deities: Personal Worship and Official Religion in Ancient Egypt.American University in Cairo Press.ISBN978-977-437-231-5.

- Grenier, J.-C. (1977).Anubis alexandrin et romain(in French). E. J. Brill.ISBN978-90-04-04917-8.