Thiamine deficiencyis a medical condition of low levels ofthiamine(vitamin B1).[1]A severe and chronic form is known asberiberi.[1][7]The name beriberi was possibly borrowed in the 18th century from theSinhalesephrase බැරි බැරි (bæri bæri, “I cannot, I cannot” ), owing to the weakness caused by the condition. The two main types in adults are wet beriberi and dry beriberi.[1]Wet beriberi affects thecardiovascular system,resulting in afast heart rate,shortness of breath,andleg swelling.[1]Dry beriberi affects thenervous system,resulting innumbness of the hands and feet,confusion, trouble moving the legs, and pain.[1]A form with loss of appetite andconstipationmay also occur.[3]Another type, acute beriberi, found mostly in babies, presents with loss of appetite, vomiting,lactic acidosis,changes in heart rate, and enlargement of the heart.[8]

| Thiamine deficiency[1] | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Beriberi, vitamin B1deficiency, thiamine-deficiency syndrome[1][2] |

| |

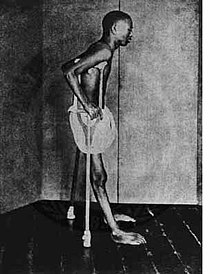

| Sufferer of beriberi in Southeast Asia beginning of the 20th Century | |

| Specialty | Neurology,cardiology,pediatrics |

| Symptoms | |

| Types | Wet, dry, gastrointestinal,[3]infantile,[4]cerebral[5] |

| Causes | Not enoughthiamine[1] |

| Risk factors | Diet of mostlywhite rice;alcoholism,dialysis,chronicdiarrhea,diuretics[1][6] |

| Prevention | Food fortification,Food diversification[1] |

| Treatment | Thiamine supplementation[1] |

| Frequency | Uncommon (USA)[1] |

Risk factors include a diet of mostlywhite rice,alcoholism,dialysis,chronicdiarrhea,and taking high doses ofdiuretics.[1][6]In rare cases, it may be due to ageneticcondition that results in difficulties absorbing thiamine found in food.[1]Wernicke encephalopathyandKorsakoff syndromeare forms of dry beriberi.[6]Diagnosis is based on symptoms, low levels of thiamine in the urine, high bloodlactate,and improvement withthiamine supplementation.[9]

Treatment is by thiamine supplementation, either by mouth or by injection.[1]With treatment, symptoms generally resolve in a few weeks.[9]The disease may be prevented at the population level through thefortification of food.[1]

Thiamine deficiency is rare in the United States.[10]It remains relatively common insub-Saharan Africa.[2]Outbreaks have been seen inrefugee camps.[6]Thiamine deficiency has been described for thousands of years in Asia, and became more common in the late 1800s with the increased processing of rice.[11]

Signs and symptoms

editSymptoms of beriberi include weight loss,emotionaldisturbances, impairedsensory perception,weaknessandpainin the limbs, and periods of irregularheart rate.Edema(swelling of bodily tissues) is common. It may increase the amount oflactic acidandpyruvic acidwithin the blood. In advanced cases, the disease may causehigh-output cardiac failureand death.

Symptoms may occur concurrently with those ofWernicke's encephalopathy,a primarily neurologicalthiamine deficiency-related condition.

Beriberi is divided into four categories. The first three are historical and the fourth, gastrointestinal beriberi, was recognized in 2004:

- Dry beriberi especially affects the peripheral nervous system.

- Wet beriberi especially affects the cardiovascular system and other bodily systems.

- Infantile beriberi affects the babies of malnourished mothers.

- Gastrointestinal beriberi affects the digestive system and other bodily systems.

Dry beriberi

editDry beriberi causes wasting and partialparalysisresulting from damaged peripheralnerves.It is also referred to as endemic neuritis. It is characterized by:

- Difficulty with walking

- Tingling or loss of sensation (numbness) in hands and feet

- Loss of tendon reflexes[12]

- Loss of muscle function or paralysis of the lower legs

- Mental confusion/speech difficulties

- Pain

- Involuntary eye movements (nystagmus)

- Vomiting

A selective impairment of the large proprioceptive sensory fibers without motor impairment can occur and present as a prominent sensoryataxia,which is a loss of balance and coordination due to loss of the proprioceptive inputs from the periphery and loss of position sense.[13]

Brain disease

editWernicke's encephalopathy(WE),Korsakoff syndrome(also called alcohol amnestic disorder), andWernicke–Korsakoff syndromeare forms of dry beriberi.[6]

Wernicke's encephalopathy is the most frequently encountered manifestation of thiamine deficiency in Western society,[14][15]though it may also occur in patients with impaired nutrition from other causes, such as gastrointestinal disease,[14]those withHIV/AIDS,and with the injudicious administration ofparenteralglucose orhyperalimentationwithout adequate B-vitamin supplementation.[16]This is a striking neuro-psychiatric disorder characterized by paralysis of eye movements, abnormal stance and gait, and markedly deranged mental function.[17]

Korsakoff syndrome,in general, is considered to occur with deterioration of brain function in patients initially diagnosed with WE.[18]This is an amnestic-confabulatory syndrome characterized byretrogradeandanterograde amnesia,impairment of conceptual functions, and decreased spontaneity and initiative.[19]

Alcoholics may have thiamine deficiency because of:

- Inadequate nutritional intake: Alcoholics tend to intake less than the recommended amount of thiamine.

- Decreased uptake of thiamine from the GI tract: Active transport of thiamine into enterocytes is disturbed during acute alcohol exposure.

- Liver thiamine stores are reduced due to hepatic steatosis or fibrosis.[20]

- Impaired thiamine utilization: Magnesium, which is required for the binding of thiamine to thiamine-using enzymes within the cell, is also deficient due to chronic alcohol consumption. The inefficient use of any thiamine that does reach the cells will further exacerbate the thiamine deficiency.

- Ethanolper seinhibits thiamine transport in the gastrointestinal system and blocks phosphorylation of thiamine to its cofactor form (ThDP).[21]

Following improved nutrition and the removal of alcohol consumption, some impairments linked with thiamine deficiency are reversed, in particular poor brain functionality, although in more severe cases, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome leaves permanent damage. (Seedelirium tremens.)

Wet beriberi

editWet beriberi affects theheartand circulatory system. It is sometimes fatal, as it causes a combination ofheart failureand weakening of thecapillarywalls, which causes the peripheral tissues to become edematous. Wet beriberi is characterized by:

- Increased heart rate

- Vasodilationleading to decreased systemic vascular resistance, and high-output heart failure[22]

- Elevatedjugular venous pressure[23]

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath) on exertion

- Paroxysmal nocturnaldyspnea

- Peripheraledema[23](swelling of lower legs) orgeneralized edema[24][25][26][27](swelling throughout the body)

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

Gastrointestinal beriberi

editGastrointestinal beriberi causes abdominal pain. It is characterized by:

Infants

editInfantile beriberi usually occurs between two and six months of age in children whose mothers have inadequate thiamine intake. It may present as either wet or dry beriberi.[2]

In the acute form, the baby developsdyspneaandcyanosisand soon dies of heart failure. These symptoms may be described in infantile beriberi:

- Hoarseness, where the child makes moves to moan, but emits no sound or just faint moans[30]caused by nerve paralysis[12]

- Weight loss, becoming thinner and thenmarasmicas the disease progresses[30]

- Vomiting[30]

- Diarrhea[30]

- Pale skin[12]

- Edema[12][30]

- Ill temper[12]

- Alterations of the cardiovascular system, especiallytachycardia(rapid heart rate)[12]

- Convulsionsoccasionally observed in the terminal stages[30]

Cause

editBeriberi is often caused by eating a diet with a very high proportion of calorie richpolished rice(common in Asia) orcassava root(common in sub-Saharan Africa), without much if anythiamine-containing animal products or vegetables.[2]

It may also be caused by shortcomings other than inadequate intake –diseasesor operations on the digestive tract,alcoholism,[23]dialysisorgenetic deficiencies.All those causes mainly affect the central nervous system, and provoke the development of Wernicke's encephalopathy.

Wernicke's disease is one of the most prevalent neurological or neuropsychiatric diseases.[31]Inautopsyseries, features of Wernicke lesions are observed in approximately 2% of general cases.[32]Medical record research shows that about 85% had not been diagnosed, although only 19% would be asymptomatic. In children, only 58% were diagnosed. Inalcohol abusers,autopsy series showed neurological damages at rates of 12.5% or more. Mortality caused by Wernicke's disease reaches 17% of diseases, which means 3.4/1000 or about 25 million contemporaries.[33][34]The number of people with Wernicke's disease may be even higher, considering that early stages may have dysfunctions prior to the production of observable lesions at necropsy. In addition, uncounted numbers of people can experience fetal damage and subsequent diseases.

Genetics

editGenetic diseases of thiamine transport are rare but serious.Thiamine responsive megaloblastic anemia syndrome(TRMA) withdiabetes mellitusandsensorineural deafness[35]is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the geneSLC19A2,[36]a high affinitythiamine transporter.TRMA patients do not show signs of systemic thiamine deficiency, suggesting redundancy in the thiamine transport system. This has led to the discovery of a second high-affinity thiamine transporter,SLC19A3.[37][38]Leigh disease(subacute necrotising encephalomyelopathy) is an inherited disorder that affects mostly infants in the first years of life and is invariably fatal. Pathological similarities between Leigh disease and WE led to the hypothesis that the cause was a defect in thiamine metabolism. One of the most consistent findings has been an abnormality of the activation of thepyruvate dehydrogenasecomplex.[39]

Mutations in theSLC19A3gene have been linked tobiotin-thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease,[40]which is treated with pharmacological doses of thiamine andbiotin,anotherB vitamin.

Other disorders in which a putative role for thiamine has been implicated includesubacute necrotising encephalomyelopathy,opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome(a paraneoplastic syndrome), andNigerian seasonal ataxia(or African seasonal ataxia). In addition, several inherited disorders of ThDP-dependent enzymes have been reported,[41]which may respond to thiamine treatment.[19]

Pathophysiology

editThiamine in the human body has a half-life of 17 days and is quickly exhausted, particularly when metabolic demands exceed intake. A derivative of thiamine,thiamine pyrophosphate(TPP), is a cofactor involved in thecitric acid cycle,as well as connecting thebreakdown of sugarswith the citric acid cycle. The citric acid cycle is a central metabolic pathway involved in the regulation of carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism, and its disruption due to thiamine deficiency inhibits the production of many molecules including the neurotransmittersglutamic acidandGABA.[42]Additionally, thiamine may also be directly involved inneuromodulation.[43]

Diagnosis

editA positive diagnosis test for thiamine deficiency involves measuring the activity of the enzymetransketolaseinerythrocytes(Erythrocyte transketolase activation assay). Alternatively, thiamine and its phosphorylated derivatives can directly be detected in whole blood, tissues, foods, animal feed, and pharmaceutical preparations following the conversion of thiamine tofluorescentthiochrome derivatives (thiochrome assay) and separation byhigh-performance liquid chromatography(HPLC).[44][45][46]Capillary electrophoresis (CE) techniques and in-capillary enzyme reaction methods have emerged as alternative techniques in quantifying and monitoring thiamine levels in samples.[47] The normal thiamine concentration in EDTA-blood is about 20–100 μg/L.

Treatment

editMany people with beriberi can be treated with thiamine alone.[48]Given thiamine intravenously (and later orally), rapid and dramatic[23]recovery occurs, generally within 24 hours.[49]

Improvements of peripheral neuropathy may require several months of thiamine treatment.[50]

Epidemiology

editBeriberi is a recurrent nutritional disease in detention houses, even in this century. In 1999, an outbreak of beriberi occurred in a detention center in Taiwan.[51]High rates of illness and death from beriberi in overcrowded Haitian jails in 2007 were traced to the traditional practice of washing rice before cooking; this removed a nutritious coating which had been applied to the rice after processing (enrichedwhite rice).[52]In theIvory Coast,among a group of prisoners with heavy punishment, 64% were affected by beriberi. Before beginning treatment, prisoners exhibited symptoms of dry or wet beriberi with neurological signs (tingling: 41%), cardiovascular signs (dyspnoea: 42%, thoracic pain: 35%), and edemas of the lower limbs (51%). With treatment, the rate of healing was about 97%.[53]

Populations under extreme stress may be at higher risk for beriberi.Displaced populations,such asrefugeesfrom war, are susceptible to micronutritional deficiency, including beriberi.[54]The severe nutritional deprivation caused byfaminealso can cause beriberis, although symptoms may be overlooked in clinical assessment or masked by other famine-related problems.[55]An extreme weight-lossdietcan, rarely, induce a famine-like state and the accompanying beriberi.[23]

Workers on Chinese squid ships are at elevated risk of beriberi due to the simple carbohydrate-rich diet they are fed and the long period of time between shoring. Between 2013 and 2021, 15 workers on 14 ships have died with symptoms of beriberi.[56]

History

editEarliest written descriptions of thiamine deficiency are from ancient China in the context ofChinese medicine.One of the earliest is byGe Hongin his bookZhou hou bei ji fang(Emergency Formulas to Keep up Your Sleeve) written sometime during the third century. Hong called the illness by the namejiao qi,which can be interpreted as "footqi".He described the symptoms to include swelling, weakness, and numbness of the feet. He also acknowledged that the illness could be deadly, and claimed that it could be cured by eating certain foods, such as fermented soybeans in wine. Better known examples of early descriptions of" foot qi "are byChao Yuanfang(who lived during 550–630) in his bookZhu bing yuan hou lun(Sources and Symptoms of All Diseases)[57][58]and bySun Simiao(581–682) in his bookBei ji qian jin yao fang(Essential Emergency Formulas Worth a Thousand in Gold).[59][58][60][61]

In the mid-19th century, interest in beriberi steadily rose as the disease became more noticeable with changes in diet in East and Southeast Asia. There was a steady uptick in medical publications, reaching one hundred and eighty-one publications from 1880 and 1889, and hundreds more in the following decades. The link to white rice was clear to Western doctors, but a confounding factor was that some other foods like meat failed to prevent beriberi, so it could not be easily explained as a lack of known chemicals like carbon or nitrogen. With no knowledge ofvitamins,theetiologyof beriberi was among the most hotly debated subjects in Victorian medicine.[62]

The first successful preventative measure against beriberi was discovered byTakaki Kanehiro,a British-trained Japanese medical doctor of theImperial Japanese Navy,in the mid-1880s.[63]Beriberi was a serious problem in the Japanese navy; sailors fell ill an average of four times a year in the period 1878 to 1881, and 35% were cases of beriberi.[63]In 1882, Takaki learned of a very high incidence of beriberi among cadets on a training mission from Japan to Hawaii, via New Zealand and South America. The voyage lasted more than nine months and resulted in 169 cases of sickness and 25 deaths on a ship of 376 men. Takaki observed that beriberi was common among low-ranking crew who were often provided free rice, thus ate little else, but not among crews of Western navies, nor among Japanese officers who consumed a more varied diet. With the support of the Japanese Navy, he conducted an experiment in which another ship was deployed on the same route, except that its crew was fed a diet of meat, fish, barley, rice, and beans. At the end of the voyage, this crew had only 14 cases of beriberi and no deaths.[63]This emphasis on varied diet contradicted observations by other doctors, and Takaki's carbon-based etiology was just as incorrect as similar theories before him, but the results of his experiment impressed the Japanese Navy, which adopted his proposed solution. By 1887 beriberi had been completely eliminated on Navy ships.[62]

In the same year, Takaki's experiment was described favorably inThe Lancet,[64]but his incorrect etiology was not taken seriously.[65]In 1897,Christiaan Eijkman,aDutchphysicianandpathologist,published his mid-1880s experiments showing that feeding unpolished rice (instead of the polished variety) to chickens helped to prevent beriberi.[66]This was the first experiment to show that not a major chemical but some minor nutrient was the true cause of beriberi. The following year, SirFrederick Hopkinspostulated that some foods contained "accessory factors" —in addition to proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and salt—that were necessary for the functions of the human body.[67][68]In 1901,Gerrit Grijns,a Dutch physician and assistant toChristiaan Eijkmanin the Netherlands, correctly interpreted beriberi as a deficiency syndrome,[69]and between 1910 and 1913,Edward Bright Vedderestablished that an extract ofrice branis a treatment for beriberi.[citation needed]In 1929, Eijkman and Hopkins were awarded theNobel Prize for Physiology or Medicinefor their discoveries.

Japanese Army denialism

editAlthough the identification of beriberi as a deficiency syndrome was proven beyond a doubt by 1913, a Japanese group headed byMori Ōgaiand backed byTokyo Imperial Universitycontinued to deny this conclusion until 1926. In 1886, Mori, then working in the Japanese Army Medical Bureau, asserted that white rice was sufficient as a diet for soldiers. Simultaneously, Navy surgeon general Takaki Kanehiro published the groundbreaking results described above. Mori, who had been educated under German doctors, responded that Takaki was a "fake doctor" due to his lack of prestigious medical background, while Mori himself and his fellow graduates of Tokyo Imperial University constituted the only "real doctors" in Japan and that they alone were capable of "experimental induction", although Mori himself had not conducted any beriberi experiments.[70]

The Japanese Navy sided with Takaki and adopted his suggestions. In order to prevent himself and the Army from losingface,Mori assembled a team of doctors and professors from Tokyo Imperial University and the Japanese Army who proposed that beriberi was caused by an unknown pathogen, which they described asetowasu(from the GermanEtwas,meaning "something" ). They employed various social tactics to denounce vitamin deficiency experiments and prevent them from being published, while beriberi ravaged the Japanese Army. During theFirst Sino-Japanese WarandRusso-Japanese War,Army soldiers continued to die in mass numbers from beriberi, while Navy sailors survived. In response to this severe loss of life, in 1907, the Army ordered the formation of a Beriberi Emergency Research Council, headed by Mori. Its members pledged to find the cause of beriberi.[71]By 1919, with most Western doctors acknowledging that beriberi was a deficiency syndrome, the Emergency Research Council began conducting experiments using various vitamins, but stressed that "more research was necessary". During this period, more than 300,000 Japanese soldiers contracted beriberi and over 27,000 died.[72]

Mori died in 1922. The Beriberi Research Council disbanded in 1925, and by the time Eijkman and Hopkins were awarded the Nobel Prize, all of its members had acknowledged that beriberi was a deficiency syndrome.

Etymology

editAlthough according to theOxford English Dictionary,the term "beriberi" comes from aSinhalesephrase meaning "weak, weak" or "I cannot, I cannot", the word beingduplicatedfor emphasis,[73]the origin of the phrase is questionable. It has also been suggested to come from Hindi, Arabic, and a few other languages, with many meanings like "weakness", "sailor", and even "sheep". Such suggested origins were listed byHeinrich Botho Scheube,among others.Edward Vedderwrote in his bookBeriberi(1913) that "it is impossible to definitely trace the origin of the word beriberi". The wordberberewas used in writing at least as early as 1568 byDiogo do Couto,when he described the deficiency in India.[74]

Kakke(Chân khí),which is a Japanese synonym for thiamine deficiency, comes from the way "jiao qi" is pronounced in Japanese.[75]"Jiao qi"is an old word used in Chinese medicine to describe beriberi.[57]"Kakke"is supposed to have entered into the Japanese language sometime between the sixth and eighth centuries.[75]

Other animals

editPoultry

editMature chickens show signs three weeks after being fed a deficient diet. In young chicks, it can appear before two weeks of age. Onset is sudden in young chicks, with anorexia and an unsteady gait. Later on, locomotor signs begin, with an apparent paralysis of the flexor of the toes. The characteristic position is called "stargazing", with the affected animal sitting on its hocks with its head thrown back in a posture calledopisthotonos.Response to administration of the vitamin is rather quick, occurring a few hours later.[76][77]

Ruminants

editPolioencephalomalacia(PEM) is the most common thiamine deficiency disorder in young ruminant and nonruminant animals. Symptoms of PEM include a profuse, but transient, diarrhea, listlessness, circling movements, stargazing or opisthotonus (head drawn back over neck), and muscle tremors.[78]The most common cause is high-carbohydrate feeds, leading to the overgrowth of thiaminase-producing bacteria, but dietary ingestion of thiaminase (e.g., inbrackenfern), or inhibition of thiamine absorption by high sulfur intake are also possible.[79]Another cause of PEM isClostridium sporogenesorBacillus aneurinolyticusinfection. These bacteria producethiaminasesthat can cause an acute thiamine deficiency in the affected animal.[80]

Snakes

editSnakes that consume a diet largely composed of goldfish and feeder minnows are susceptible to developing thiamine deficiency. This is often a problem observed in captivity when keeping garter and ribbon snakes that are fed a goldfish-exclusive diet, as these fish contain thiaminase, an enzyme that breaks down thiamine.[81]

Wild birds and fish

editThiamine deficiency has been identified as the cause of a paralytic disease affecting wild birds in the Baltic Sea area dating back to 1982.[82]In this condition, there is difficulty in keeping the wings folded along the side of the body when resting, loss of the ability to fly and voice, with eventual paralysis of the wings and legs and death. It affects primarily 0.5–1 kg-sized birds such as theEuropean herring gull(Larus argentatus),common starling(Sturnus vulgaris), andcommon eider(Somateria mollissima). Researchers noted, "Because the investigated species occupy a wide range of ecological niches and positions in the food web, we are open to the possibility that other animal classes may develop thiamine deficiency, as well."[82]p. 12006

In the counties ofBlekingeandSkåne,mass deaths of several bird species, especially the European herring gull, have been observed since the early 2000s. More recently, species of other classes seems to be affected. High mortality ofsalmon(Salmo salar) in the riverMörrumsånis reported, and mammals such as theEurasian elk(Alces alces) have died in unusually high numbers. Lack of thiamine is the common denominator where analysis is done. In April 2012, the County Administrative Board of Blekinge found the situation so alarming that they asked the Swedish government to set up a closer investigation.[83]

References

edit- ^abcdefghijklmnopqr"Beriberi".Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program.2015.Archivedfrom the original on 11 November 2017.Retrieved11 November2017.

- ^abcdAdamolekun B, Hiffler L (24 October 2017)."A diagnosis and treatment gap for thiamine deficiency disorders in sub-Saharan Africa?".Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.1408(1): 15–19.Bibcode:2017NYASA1408...15A.doi:10.1111/nyas.13509.PMID29064578.

- ^abFerri FF (2017).Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1.Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1368.ISBN978-0-323-52957-0.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-11-11.

- ^"Pediatric Beriberi Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination".emedicine.medscape.Retrieved2024-04-10.

- ^Arányi J (1991-11-24)."[Cerebral beriberi with ophthalmoplegia as the leading symptom in an alcoholic patient]".Orvosi Hetilap.132(47): 2627–2628.ISSN0030-6002.PMID1956687.

- ^abcde"Nutrition and Growth Guidelines".Domestic Guidelines - Immigrant and Refugee Health. CDC. March 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 11 November 2017.Retrieved11 November2017.

- ^Hermann W, Obeid R (2011).Vitamins in the prevention of human diseases.Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 58.ISBN978-3-11-021448-2.

- ^Gropper SS, Smith JL (2013).Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism(6 ed.). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 324.ISBN978-1-133-10405-6.

- ^abSwaiman KF, Ashwal S, Ferriero DM, Schor NF, Finkel RS, Gropman AL, Pearl PL, Shevell M (2017).Swaiman's Pediatric Neurology E-Book: Principles and Practice.Elsevier Health Sciences. p. e929.ISBN978-0-323-37481-1.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-11-11.

- ^"Thiamine Fact Sheet for Consumers".Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS): USA.gov.Archivedfrom the original on October 29, 2017.RetrievedApril 10,2018.

- ^Lanska DJ (2010). "Chapter 30 Historical aspects of the major neurological vitamin deficiency disorders: The water-soluble B vitamins".History of Neurology.Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 95. pp. 445–76.doi:10.1016/S0072-9752(08)02130-1.ISBN978-0-444-52009-8.PMID19892133.

- ^abcdefKatsura E, Oiso T (1976). Beaton G, Bengoa J (eds.)."Chapter 9. Beriberi"(PDF).World Health Organization Monograph Series No. 62: Nutrition in Preventive Medicine.Geneva:World Health Organization.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-08.

- ^Spinazzi M, Angelini C, Patrini C (2010). "Subacute sensory ataxia and optic neuropathy with thiamine deficiency".Nature Reviews Neurology.6(5): 288–93.doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2010.16.PMID20308997.S2CID12333200.

- ^abKril JJ (1996). "Neuropathology of thiamine deficiency disorders".Metab Brain Dis.11(1): 9–17.doi:10.1007/BF02080928.PMID8815394.S2CID20889916.

- ^For an interesting discussion on thiamine fortification of foods, specifically targetting beer, see"Wernicke's encephalopathy and thiamine fortification of food: time for a new direction?".Medical Journal of Australia.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-08-31.

- ^Butterworth RF, Gaudreau C, Vincelette J, et al. (1991). "Thiamine deficiency and Wernicke's encephalopathy in AIDS".Metab Brain Dis.6(4): 207–12.doi:10.1007/BF00996920.PMID1812394.S2CID8833558.

- ^Harper C (1979)."Wernicke's encephalopathy, a more common disease than realised (a neuropathological study of 51 cases)".J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.42(3): 226–231.doi:10.1136/jnnp.42.3.226.PMC490724.PMID438830.

- ^McCollum EVA History of Nutrition.Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, Houghton Mifflin; 1957.

- ^abButterworth RF. Thiamin. In: Shils ME, Shike M, Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, editors. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 10th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- ^Butterworth RF (1993). "Pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for the reversible (thiamine-responsive) and irreversible (thiamine non-responsive) neurological symptoms of Wernicke's encephalopathy".Drug Alcohol Rev.12(3): 315–22.doi:10.1080/09595239300185371.PMID16840290.

- ^Rindi G, Imarisio L, Patrini C (1986). "Effects of acute and chronic ethanol administration on regional thiamin pyrophosphokinase activity of the rat brain".Biochem Pharmacol.35(22): 3903–8.doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90002-X.PMID3022743.

- ^Anand IS, Florea VG (2001). "High Output Cardiac Failure".Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine.3(2): 151–159.doi:10.1007/s11936-001-0070-1.PMID11242561.S2CID44475541.

- ^abcdeMcIntyre N, Stanley NN (1971)."Cardiac Beriberi: Two Modes of Presentation".BMJ.3(5774): 567–9.doi:10.1136/bmj.3.5774.567.PMC1798841.PMID5571454.

- ^Lee HS, Lee SA, Shin HS, Choi HM, Kim SJ, Kim HK, Park YB (August 2013)."A case of cardiac beriberi: a forgotten but memorable disease".Korean Circulation Journal.43(8): 569–572.doi:10.4070/kcj.2013.43.8.569.ISSN1738-5520.PMC3772304.PMID24044018.

- ^Tanabe N, Hiraoka E, Kataoka J, Naito T, Matsumoto K, Arai J, Norisue Y (March 2018)."Wet Beriberi Associated with Hikikomori Syndrome".Journal of General Internal Medicine.33(3): 384–387.doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4208-6.ISSN1525-1497.PMC5834955.PMID29188542.

- ^Watson JT, El Bushra H, Lebo EJ, Bwire G, Kiyengo J, Emukule G, Omballa V, Tole J, Zuberi M, Breiman RF, Katz MA (2011)."Outbreak of beriberi among African Union troops in Mogadishu, Somalia".PLOS ONE.6(12): e28345.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628345W.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028345.ISSN1932-6203.PMC3244391.PMID22205947.

- ^Toyonaga J, Masutani K, Tsuruya K, Haruyama N, Sugiwaka S, Suehiro T, Maeda H, Taniguchi M, Katafuchi R, Iida M (October 2009). "Severe anasarca due to beriberi heart disease and diabetic nephropathy".Clinical and Experimental Nephrology.13(5): 518–521.doi:10.1007/s10157-009-0189-z.ISSN1437-7799.PMID19459028.S2CID38559672.

- ^Donnino M (2004). "Gastrointestinal Beriberi: A Previously Unrecognized Syndrome".Ann Intern Med.141(11): 898–899.doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00035.PMID15583247.

- ^Duca, J., Lum, C., & Lo, A. (2015). Elevated Lactate Secondary to Gastrointestinal Beriberi. J GEN INTERN MED Journal of General Internal Medicine

- ^abcdefLatham MC (1997)."Chapter 16. Beriberi and thiamine deficiency".Human nutrition in the developing world (Food and Nutrition Series – No. 29).Fao Food and Nutrition Series. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).ISSN1014-3181.Archivedfrom the original on 2014-02-03.

- ^Cernicchiaro L (2007)."Enfermedad de Wernicke (o Encefalopatía de Wernicke). Monitoring an acute and recovered case for twelve years"[Wernicke´s Disease (or Wernicke´s Encephalopathy)] (in Spanish).Archivedfrom the original on 2013-05-22.

- ^Salen PN (1 March 2013). Kulkarni R (ed.)."Wernicke Encephalopathy".Medscape.Archivedfrom the original on 12 May 2013.

- ^Harper CG, Giles M, Finlay-Jones R (April 1986)."Clinical signs in the Wernicke-Korsakoff complex: a retrospective analysis of 131 cases diagnosed at necropsy".J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.49(4): 341–5.doi:10.1136/jnnp.49.4.341.PMC1028756.PMID3701343.

- ^Harper C (March 1979)."Wernicke's encephalopathy: a more common disease than realised. A neuropathological study of 51 cases".J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.42(3): 226–31.doi:10.1136/jnnp.42.3.226.PMC490724.PMID438830.

- ^Slater PV (1978). "Thiamine Responsive Megaloblastic Anemia with severe diabetes mellitus and sensorineural deafness (TRMA)".The Australian Nurses' Journal.7(11): 40–3.PMID249270.

- ^Kopriva V, Bilkovic, R, Licko, T (Dec 1977). "Tumours of the small intestine (author's transl)".Ceskoslovenska Gastroenterologie a Vyziva.31(8): 549–53.ISSN0009-0565.PMID603941.

- ^Beissel J (Dec 1977). "The role of right catheterization in valvular prosthesis surveillance (author's transl)".Annales de Cardiologie et d'Angéiologie.26(6): 587–9.ISSN0003-3928.PMID606152.

- ^Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man(OMIM):249270

- ^Butterworth RF. Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency disorders. In: McCandless DW, ed.Cerebral Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Encephalopathy.Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1985.

- ^Tabarki B, Al-Hashem A, Alfadhel M (July 28, 1993). "Biotin-Thiamine-Responsive Basal Ganglia Disease". In Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Mirzaa G, Amemiya A (eds.).GeneReviews®.University of Washington, Seattle.PMID24260777.Archived fromthe originalon May 9, 2018 – via PubMed.

- ^Blass JP. Inborn errors of pyruvate metabolism. In: Stanbury JB, Wyngaarden JB, Frederckson DS et al., eds.Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease.5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983.

- ^Sechi G, Serra A (May 2007). "Wernicke's encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management".Lancet Neurology.6(5): 442–55.doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70104-7.PMID17434099.S2CID15523083.

- ^Hirsch JA, Parrott J (2012). "New considerations on the neuromodulatory role of thiamine".Pharmacology.89(1–2): 111–6.doi:10.1159/000336339.PMID22398704.S2CID22555167.

- ^Bettendorff L, Peeters M, Jouan C, Wins P, Schoffeniels E (1991). "Determination of thiamin and its phosphate esters in cultured neurons and astrocytes using an ion-pair reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatographic method".Anal. Biochem.198(1): 52–59.doi:10.1016/0003-2697(91)90505-N.PMID1789432.

- ^Losa R, Sierra MI, Fernández A, Blanco D, Buesa J (2005). "Determination of thiamine and its phosphorylated forms in human plasma, erythrocytes and urine by HPLC and fluorescence detection: a preliminary study on cancer patients".J Pharm Biomed Anal.37(5): 1025–1029.doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2004.08.038.PMID15862682.

- ^Lu J, Frank E (May 2008)."Rapid HPLC measurement of thiamine and its phosphate esters in whole blood".Clin. Chem.54(5): 901–906.doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.099077.PMID18356241.

- ^Shabangi M, Sutton J (2005). "Separation of thiamin and its phosphate esters by capillary zone electrophoresis and its application to the analysis of water-soluble vitamins".Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis.38(1): 66–71.doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2004.11.061.PMID15907621.

- ^Dieu-Thu Nguyen-Khoa, Ginette V Busschots, Phyllis A Vallee (2022-06-29), Romesh Khardori (ed.),"Beriberi (Thiamine Deficiency) Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Activity",Medscape,archived fromthe originalon 2014-03-24

- ^Tanphaichitr V. Thiamin. In: Shils ME, Olsen JA, Shike M et al., editors.Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease.9th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999

- ^Maurice V, Adams RD, Collins GH.The Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome and Related Neurologic Disorders Due to Alcoholism and Malnutrition.2nd ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1989.

- ^Chen KT, Twu SJ, Chiou ST, Pan WH, Chang HJ, Serdula MK (2003)."Outbreak of beriberi among illegal mainland Chinese immigrants at a detention center in Taiwan".Public Health Rep.118(1): 59–64.doi:10.1093/phr/118.1.59.PMC1497506.PMID12604765.

- ^Sprague J, Alexandra E (17 January 2007)."Haiti: Mysterious Prison Ailment Traced to U.S. Rice".Inter Press Service.Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2013.

- ^Aké-Tano O, Konan EY, Tetchi EO, Ekou FK, Ekra D, Coulibaly A, Dagnan NS (2011). "Le béribéri, maladie nutritionnelle récurrente en milieu carcéral en Côte-d'Ivoire".Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique.104(5): 347–351.doi:10.1007/s13149-011-0136-6.PMID21336653.S2CID116433417.

- ^Prinzo ZW, de Benoist B (2009)."Meeting the challenges of micronutrient deficiencies in emergency-affected populations"(PDF).Proceedings of the Nutrition Society.61(2): 251–7.doi:10.1079/PNS2002151.PMID12133207.S2CID8286320.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2012-10-19.

- ^Golden M (May 1997)."Diagnosing Beriberi in Emergency Situations".Field Exchange(1): 18. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-10-19.

- ^Ian Urbina, Joe Galvin, Maya Martin, Susan Ryan, Daniel Murphy, Austin Brush (7 November 2023)."They catch squid for the world's table. But deckhands on Chinese ships pay a deadly price".Los Angeles Times.

- ^abHA Smith, p. 26-28

- ^abBenedict CA (October 2018). "Forgotten Disease: Illnesses Transformed in Chinese Medicine by Hilary A. Smith (review)".Bulletin of the History of Medicine.92(3): 550–51.doi:10.1353/bhm.2018.0059.ISSN1086-3176.S2CID80778431.

- ^HA Smith, p. 44

- ^"TCM history V the Sui & Tang Dynasties".Archivedfrom the original on 2017-07-14.Retrieved2017-07-11.

- ^"Sun Simiao: Author of the Earliest Chinese Encyclopedia for Clinical Practice".Archivedfrom the original on 2007-07-04.Retrieved2007-06-15.

- ^abCarter KC (April 1977)."The germ theory, beriberi, and the deficiency theory of disease"(PDF).Medical History.21(2): 126–7.doi:10.1017/S0025727300037662.ISSN2048-8343.PMC1081945.PMID325303.

- ^abcItokawa Y (1976). "Kanehiro Takaki (1849–1920): A Biographical Sketch".Journal of Nutrition.106(5): 581–8.doi:10.1093/jn/106.5.581.PMID772183.

- ^The Lancet.J. Onwhyn. 1887.

- ^Yamashita N, Aikawa T (1 March 2017)."Dutch Research on Beriberi: I. Christiaan Eijkman's Research and Evaluation of Kanehiro Takaki's Diet Reforms of the Japanese Navy".Nihon ishigaku zasshi [Journal of Japanese history of medicine].63(1): 3–21.ISSN0549-3323.PMID30549780.

- ^Eijkman C (June 1897)."Eine Beri Beri-ähnliche Krankheit der Hühner".Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin(in German).148(3): 523–32.doi:10.1007/BF01937576.ISSN1432-2307.

- ^Challem J (1997)."The Past, Present and Future of Vitamins".Archived fromthe originalon 8 June 2010.[unreliable medical source?]

- ^"Christiaan Eijkman, Beriberi and Vitamin B1".Nobelprize.org, Nobel Media AB.Archivedfrom the original on 17 January 2010.Retrieved8 July2013.

- ^Grijns G (1901). "Over polyneuritis gallinarum".Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indie.43:3–110.

- ^Kim He (2014).Doctors of empire: medical and cultural encounters between imperial Germany and Meiji Japan.Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 146.ISBN9781442644403.

- ^Padilla RR (April 2023)."Efficacy vs. Ideology: The Use of Food Therapies in Preventing and Treating Beriberi in the Japanese Army in the Meiji Era".East Asian Science, Technology and Society.17(2): 201–21.doi:10.1080/18752160.2022.2071191.ISSN1875-2160.S2CID251484808.

- ^Bay A (2011)."Ōgai Mori rintarō to kakkefunsō âu ngoại Mori Rintarou と chân khí phân tranh [Mori Ōgai and the Beriberi Dispute] (review)".East Asian Science, Technology and Society.5(4): 573–79.doi:10.1215/18752160-1458784.ISSN1875-2152.S2CID222093508.

- ^Oxford English Dictionary:"Beri-beri... a Cingalese word, f.beriweakness, the reduplication being intensive... ", page 203, 1937

- ^HA Smith, p. 118-119

- ^abHA Smith, p. 149

- ^R.E. Austic and M.L. Scott, Nutritional deficiency diseases, inDiseases of poultry,ed. by M. S. Hofstad. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press.ISBN0-8138-0430-2.p. 50.

- ^"Thiamine Deficiency".Merck Veterinary Manual.2008.Retrieved2023-02-16.

- ^National Research Council. 1996.Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle,Seventh Revised Ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ^Michel Lévy, ed. (March 2015)."Overview of Polioencephalomalacia".Merck Veterinary Manual.Archived fromthe originalon 2016-03-03.Retrieved2023-02-16.

- ^Polioencephalomacia: IntroductionArchived2010-05-28 at theWayback Machine,"ACES Publications"

- ^"Update on Common Nutritional Disorders of Captive Reptiles".Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-13.Retrieved2017-09-13.

- ^abBalk L, Hägerroth PA, Akerman G, Hanson M, Tjärnlund U, Hansson T, Hallgrimsson GT, Zebühr Y, Broman D, Mörner T, Sundberg H, et al. (2009)."Wild birds of declining European species are dying from a thiamine deficiency syndrome".Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.106(29): 12001–12006.Bibcode:2009PNAS..10612001B.doi:10.1073/pnas.0902903106.PMC2715476.PMID19597145.

- ^Blekinge län L (2013)."2012-04-15 500-1380-13 Förhöjd dödlighet hos fågel, lax og älg"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2013-12-02.

Further reading

edit- Arnold D (2010)."British India and the beri-beri problem".Medical History.54(3): 295–314.doi:10.1017/S0025727300004622.PMC2889456.PMID20592882.

- Chisholm H,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 774–775.

- Smith HA (2017).Forgotten Disease: Illnesses Transformed in Chinese Medicine.doi:10.1093/jhmas/jry029.ISBN978-1-5036-0350-9.OCLC993877848.

External links

edit- Media related toBeriberiat Wikimedia Commons