Abone scanorbone scintigraphy/sɪnˈtɪɡrəfi/is anuclear medicineimaging technique used to help diagnose and assess different bone diseases. These includecancer of the boneormetastasis,location of boneinflammationandfractures(that may not be visible in traditionalX-ray images), and bone infection (osteomyelitis).[1]

| Bone scintigraphy | |

|---|---|

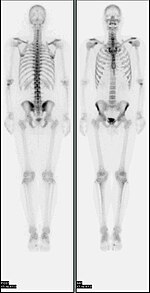

A nuclear medicine whole-body bone scan. The nuclear medicine whole-body bone scan is generally used in evaluations of various bone-related pathology, such as for bone pain, stress fracture, nonmalignant bone lesions, bone infections, or the spread of cancer to the bone. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 92.14 |

| OPS-301 code | 3-705 |

| MedlinePlus | 003833 |

Nuclear medicine provides functional imaging and allows visualisation ofbone metabolismorbone remodeling,which most other imaging techniques (such as X-raycomputed tomography,CT) cannot.[2][3]Bonescintigraphycompetes withpositron emission tomography(PET) for imaging of abnormal metabolism in bones, but is considerably less expensive.[4]Bone scintigraphy has highersensitivitybut lower specificity than CT or MRI for diagnosis ofscaphoid fracturesfollowing negativeplain radiography.[5]

History

editSome of the earliest investigations into skeletal metabolism were carried out byGeorge de Hevesyin the 1930s, usingphosphorus-32and byCharles Pecherin the 1940s.[6][7]

In the 1950s and 1960s calcium-45 was investigated, but as abeta emitterproved difficult to image. Imaging ofpositronandgamma emitterssuch asfluorine-18andisotopes of strontiumwithrectilinear scannerswas more useful.[8][9]Use oftechnetium-99m(99mTc) labelledphosphates,diphosphonatesor similar agents, as in the modern technique, was first proposed in 1971.[10][11]

Principle

editThe most commonradiopharmaceuticalfor bone scintigraphy is99mTc withmethylene diphosphonate(MDP).[12]Other bone radiopharmaceuticals include99mTc with HDP, HMDP and DPD.[13][14]MDPadsorbsonto the crystallinehydroxyapatitemineral of bone.[15]Mineralisation occurs atosteoblasts,representing sites of bone growth, where MDP (and other diphosphates) "bind to the hydroxyapatite crystals in proportion to local blood flow andosteoblasticactivity and are therefore markers of bone turnover and bone perfusion ".[16][17]

The more active thebone turnover,the more radioactive material will be seen. Sometumors,fracturesandinfectionsshow up as areas of increased uptake.[18]

Note that the technique depends on the osteoblastic activity during remodelling and repair processes following initial osteolytic activity. This leads to a limitation of the applicability of this imaging technique with diseases not featuring this osteoblastic (reactive) activity, for example withmultiple myeloma.Scintigraphic images remain falsely negative for a long period of time and therefore have only limited diagnostic value. In these cases CT or MRI scans are preferred for diagnosis and staging.

Technique

editIn a typical bone scan technique, the patient is injected (usually into a vein in the arm or hand, occasionally the foot) with up to 740MBqoftechnetium-99m-MDPand then scanned with agamma camera,which captures planaranteriorand posterior orsingle photon emission computed tomography(SPECT) images.[19][14]In order to view small lesions SPECT imaging technique may be preferred over planar scintigraphy.[20]

In a single phase protocol (skeletal imaging alone), which will primarily highlight osteoblasts, images are usually acquired 2–5 hours after the injection (after four hours 50–60% of the activity will be fixed to bones).[19][14][21]A two or three phase protocol utilises additional scans at different points after the injection to obtain additional diagnostic information. A dynamic (i.e. multiple acquired frames) study immediately after the injection capturesperfusioninformation.[21][22]A second phase "blood pool" image following the perfusion (if carried out in a three phase technique) can help to diagnose inflammatory conditions or problems of blood supply.[23]

A typicaleffective doseobtained during a bone scan is 6.3millisieverts(mSv).[24]

-

Person undergoing a bone scan on the skull

-

A patient undergoing a SPECT bone scan.

PET bone imaging

editAlthough bone scintigraphy generally refers to gamma camera imaging of99mTc radiopharmaceuticals, imaging withpositron emission tomography(PET) scanners is also possible, usingfluorine-18sodium fluoride([18F]NaF).

Forquantitativemeasurements,99mTc-MDP has some advantages over [18F]NaF. MDP renal clearance is not affected by urine flow rate and simplified data analysis can be employed which assumessteady stateconditions. It has negligible tracer uptake inred blood cells,therefore correction for plasma to whole blood ratios is not required unlike [18F]NaF. However, disadvantages include higher rates of protein binding (from 25% immediately after injection to 70% after 12 hours leading to the measurement of freely available MDP over time), and lessdiffusibilitydue to highermolecular weightthan [18F]NaF, leading to lowercapillary permeability.[25]

There are several advantages of the PET technique, which are common to PET imaging in general, including improvedspatial resolutionand more developedattenuationcorrection techniques. Patient experience is improved as imaging can be started much more quickly following radiopharmaceutical injection (30–45 minutes, compared to 2–3 hours for MDP/HDP).[26][27][18F]NaF PET is hampered by high demand for scanners, and limited tracer availability.[28][29]

References

edit- ^Bahk, Yong-Whee (2000).Combined scintigraphic and radiographic diagnosis of bone and joint diseases(2nd ed.). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. p. 3.ISBN9783662041062.

- ^Ćwikła, Jarosław B. (2013)."New imaging techniques in reumathology: MRI, scintigraphy and PET".Polish Journal of Radiology.78(3): 48–56.doi:10.12659/PJR.889138.PMC3789933.PMID24115960.

- ^Livieratos, Lefteris (2012). "Basic Principles of SPECT and PET Imaging". In Fogelman, Ignac; Gnanasegaran, Gopinath; van der Wall, Hans (eds.).Radionuclide and Hybrid Bone Imaging.Berlin: Springer. p. 345.doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02400-9_12.ISBN978-3-642-02399-6.

- ^O'Sullivan, Gerard J (2015)."Imaging of bone metastasis: An update".World Journal of Radiology.7(8): 202–11.doi:10.4329/wjr.v7.i8.202.PMC4553252.PMID26339464.

- ^Mallee, WH; Wang, J; Poolman, RW; Kloen, P; Maas, M; de Vet, HC; Doornberg, JN (5 June 2015)."Computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging versus bone scintigraphy for clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in patients with negative plain radiographs".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2015(6): CD010023.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010023.pub2.PMC6464799.PMID26045406.

- ^Pecher, Charles (1941). "Biological Investigations with Radioactive Calcium and Strontium".Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine.46(1): 86–91.doi:10.3181/00379727-46-11899.ISSN0037-9727.S2CID88173163.

- ^Carlson, Sten (8 July 2009)."A Glance At The History Of Nuclear Medicine".Acta Oncologica.34(8): 1095–1102.doi:10.3109/02841869509127236.PMID8608034.

- ^Bridges, R. L.; Wiley, C. R.; Christian, J. C.; Strohm, A. P. (11 May 2007)."An Introduction to Na18F Bone Scintigraphy: Basic Principles, Advanced Imaging Concepts, and Case Examples".Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology.35(2): 64–76.doi:10.2967/jnmt.106.032870.PMID17496010.

- ^Fleming, William H.; McIlraith, James D.; Richard King, Capt. E. (October 1961). "Photoscanning of Bone Lesions Utilizing Strontium 85".Radiology.77(4): 635–636.doi:10.1148/77.4.635.PMID13893538.

- ^Subramanian, G.; McAfee, J. G. (April 1971). "A New Complex of 99mTc for Skeletal Imaging".Radiology.99(1): 192–196.doi:10.1148/99.1.192.PMID5548678.

- ^Fogelman, I (2013). "The Bone Scan—Historical Aspects".Bone Scanning in Clinical Practice.London: Springer. pp. 1–6.doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-1407-9_1.ISBN978-1-4471-1409-3.

- ^Biersack, Hans-Jürgen; Freeman, Leonard M.; Zuckier, Lionel S.; Grünwald, Frank (2007).Clinical Nuclear Medicine.Berlin: Springer. p. 243.ISBN9783540280255.

- ^Weissman, Barbara N (2009).Imaging of Arthritis and Metabolic Bone Disease.Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 17.ISBN978-0-323-04177-5.

- ^abcVan den Wyngaert, T.; Strobel, K.; Kampen, W. U.; Kuwert, T.; van der Bruggen, W.; Mohan, H. K.; Gnanasegaran, G.; Delgado-Bolton, R.; Weber, W. A.; Beheshti, M.; Langsteger, W.; Giammarile, F.; Mottaghy, F. M.; Paycha, F. (4 June 2016)."The EANM practice guidelines for bone scintigraphy".European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging.43(9): 1723–1738.doi:10.1007/s00259-016-3415-4.PMC4932135.PMID27262701.

- ^Chopra, A (24 August 2009)."99mTc-Methyl diphosphonate ".Molecular Imaging and Contrast Agent Database.National Center for Biotechnology Information (US).PMID20641923.

- ^Brenner, Arnold I.; Koshy, June; Morey, Jose; Lin, Cheryl; DiPoce, Jason (January 2012). "The Bone Scan".Seminars in Nuclear Medicine.42(1): 11–26.doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2011.07.005.PMID22117809.

- ^Wong, K. K.; Piert, M. (12 March 2013)."Dynamic Bone Imaging with 99mTc-Labeled Diphosphonates and 18F-NaF: Mechanisms and Applications".Journal of Nuclear Medicine.54(4): 590–599.doi:10.2967/jnumed.112.114298.PMID23482667.

- ^Verberne, SJ; Raijmakers, PG; Temmerman, OP (5 October 2016)."The Accuracy of Imaging Techniques in the Assessment of Periprosthetic Hip Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis".The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume.98(19): 1638–1645.doi:10.2106/jbjs.15.00898.PMID27707850.S2CID9202184.Archived fromthe originalon 16 December 2016.Retrieved20 November2016.

- ^abDonohoe, Kevin J.; Brown, Manuel L.; Collier, B. David; Carretta, Robert F.; Henkin, Robert E.; O'Mara, Robert E.; Royal, Henry D. (20 June 2003).Procedure Guideline for Bone Scintigraphy(PDF)(Report). Society of Nuclear Medicine. 3.0.

- ^Kane, Tom; Kulshrestha, Randeep; Notghi, Alp; Elias, Mark (2013)."Clinical Utility (Applications) of SPECT/CT".In Wyn Jones, David; Hogg, Peter; Seeram, Euclid (eds.).Practical SPECT/CT in nuclear medicine.London: Springer. p. 197.ISBN9781447147039.

- ^ab"Clinical Guideline for Bone Scintigraphy"(PDF).BNMS. July 2014.

- ^Weissman, Barbara N. (2009).Imaging of arthritis and metabolic bone disease.Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p.18.ISBN9780323041775.

- ^Schauwecker, D S (January 1992). "The scintigraphic diagnosis of osteomyelitis".American Journal of Roentgenology.158(1): 9–18.doi:10.2214/ajr.158.1.1727365.PMID1727365.

- ^Mettler, Fred A.; Huda, Walter; Yoshizumi, Terry T.; Mahesh, Mahadevappa (July 2008). "Effective Doses in Radiology and Diagnostic Nuclear Medicine: A Catalog".Radiology.248(1): 254–263.doi:10.1148/radiol.2481071451.PMID18566177.

- ^Moore, A. E.B.; Blake, G. M.; Fogelman, I. (2008-02-20)."Quantitative Measurements of Bone Remodeling Using 99mTc-Methylene Diphosphonate Bone Scans and Blood Sampling".Journal of Nuclear Medicine.49(3): 375–382.doi:10.2967/jnumed.107.048595.ISSN0161-5505.PMID18287266.

- ^Segall, G.; Delbeke, D.; Stabin, M. G.; Even-Sapir, E.; Fair, J.; Sajdak, R.; Smith, G. T. (4 November 2010)."SNM Practice Guideline for Sodium 18F-Fluoride PET/CT Bone Scans 1.0".Journal of Nuclear Medicine.51(11): 1813–1820.doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.082263.PMID21051652.

- ^Beheshti, M.; Mottaghy, F. M.; Payche, F.; Behrendt, F. F. F.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Fogelman, I.; Strobel, K.; Celli, M.; Fanti, S.; Giammarile, F.; Krause, B.; Langsteger, W. (23 July 2015)."18F-NaF PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for bone imaging".European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging.42(11): 1767–1777.doi:10.1007/s00259-015-3138-y.PMID26201825.

- ^Langsteger, Werner; Rezaee, Alireza; Pirich, Christian; Beheshti, Mohsen (November 2016). "18F-NaF-PET/CT and 99mTc-MDP Bone Scintigraphy in the Detection of Bone Metastases in Prostate Cancer".Seminars in Nuclear Medicine.46(6): 491–501.doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2016.07.003.PMID27825429.

- ^Beheshti, Mohsen (October 2018). "18F-Sodium Fluoride PET/CT and PET/MR Imaging of Bone and Joint Disorders".PET Clinics.13(4): 477–490.doi:10.1016/j.cpet.2018.05.004.PMID30219183.S2CID52280057.

External links

edit- "Bone scans".WebMD.RetrievedJuly 9,2008.