CD93(Cluster ofDifferentiation 93) is aproteinthat in humans is encoded by theCD93gene.[5][6][7]CD93 is aC-type lectintransmembrane receptorwhich plays a role not only in cell–cell adhesion processes but also in host defense.[7]

| CD93 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | CD93,C1QR1, C1qR(P), C1qRP, CDw93, ECSM3, MXRA4, dJ737E23.1, CD93 molecule | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM:120577;MGI:106664;HomoloGene:7823;GeneCards:CD93;OMA:CD93 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Family

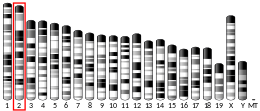

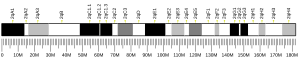

editCD93 belongs to the Group XIV C-Typelectinfamily,[8]a group containing three other members, endosialin (CD248), CLEC14A[9]andthrombomodulin,a well characterized anticoagulant. All of them contain a C-type lectin domain, a series ofepidermal growth factor like domains,a highly glycosylated mucin-like domain, a unique transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic tail. Due to their strong homology and their close proximity on chromosome 20, CD93 has been suggested to have arisen from the thrombomodulin gene through aduplicationevent.

Expression

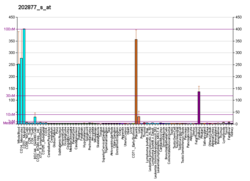

editCD93 was originally identified in mice as an earlyB cellmarker through the use of AA4.1 monoclonal antibody.[10][11]Then this molecule was shown to be expressed on an early population ofhematopoietic stem cells,which give rise to the entire spectrum of mature cells in the blood. Now CD93 is known to be expressed by a wide variety of cells such asplatelets,monocytes,microgliaandendothelialcells. In the immune system CD93 is also expressed onneutrophils,activatedmacrophages,B cell precursors until the T2 stage in the spleen, a subset of dendritic cells and of natural killer cells. Molecular characterization of CD93 revealed that this protein is identical with C1qRp, a human protein identified as a putativeC1qreceptor.[12]C1q belongs to thecomplementactivation proteins and plays a major role in the activation of the classical pathway of the complement, which leads to the formation of the membrane attack complex. C1q is also involved in other immunological processes such as enhancement of bacterial phagocytosis, clearance ofapoptoticcells or neutralisation of virus. Strikingly, it has been shown that anti-C1qRp significantly reduced C1q enhanced phagocytosis. A more recent study confirmed that C1qRp is identical to CD93 protein, but failed to demonstrate a direct interaction between CD93 and C1q under physiological conditions. Recently it has been shown that CD93 is re-expressed during the late B cell differentiation and CD93 can be used in this context as a plasma cell maturation marker. CD93 has been found to be differentially expressed in grade IV glioma vasculature when compared to low grade glioma or normal brain and its high expression correlated with the poor survival of the patients.[13][14]

Function

editCD93 was initially thought to be a receptor for C1q, but now is thought to instead be involved in intercellularadhesionand in the clearance of apoptotic cells. The intracellular cytoplasmic tail of this protein contains two highly conserved domains which may be involved in CD93 function. Indeed, the highly charged juxtamembrane domain has been found to interact withmoesin,a protein known to play a role in linking transmembrane proteins to thecytoskeletonand in the remodelling of the cytoskeleton. This process appears crucial for both adhesion,migrationandphagocytosis,three functions in which CD93 may be involved.

In the context of late B cell differentiation, CD93 has been shown to be important for the maintenance of high antibody titres after immunization and in the survival oflong-lived plasma cellsin the bone marrow. Indeed, CD93 deficient mice failed to maintain high antibody level upon immunization and present a lower amount of antigen specific plasma cells in the bone marrow.

In the context of the endothelial cells, CD93 is involved in endothelial cell-cell adhesion, cell spreading, cell migration, cell polarization as well as tubular morphogenesis.[14]Recently it has been found that CD93 is able to control endothelial cell dynamics through its interaction with an extracellular matrix glycoprotein MMRN2.[15]Absence of CD93 or its interacting partner MMRN2 in the endothelial cells lead to disruption of extracellular matrix proteinfibronectinfibrillogenesis and decreasedintegrin B1activation.[15]

CD93 plays a significant role in the glioma development. CD93 knockout mice with glioma show smaller tumor size and improved survival.[14]The tumors also show disrupted fibronectin fibrillogenesis and decreasedintegrin B1activation.[15]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^abcGRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000125810–Ensembl,May 2017

- ^abcGRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000027435–Ensembl,May 2017

- ^"Human PubMed Reference:".National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^"Mouse PubMed Reference:".National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^Nepomuceno RR, Henschen-Edman AH, Burgess WH, Tenner AJ (February 1997)."cDNA cloning and primary structure analysis of C1qR(P), the human C1q/MBL/SPA receptor that mediates enhanced phagocytosis in vitro".Immunity.6(2): 119–29.doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80419-7.PMID9047234.

- ^Webster SD, Park M, Fonseca MI, Tenner AJ (January 2000). "Structural and functional evidence for microglial expression of C1qR(P), the C1q receptor that enhances phagocytosis".Journal of Leukocyte Biology.67(1): 109–16.doi:10.1002/jlb.67.1.109.PMID10648005.S2CID14982216.

- ^ab"Entrez Gene: CD93 CD93 molecule".

- ^Khan KA, McMurray J, Mohammed FM, Bicknell R (2019)."C-type lectin domain group 14 proteins in vascular biology, cancer and inflammation".FEBS Journal.286(17): 3299–3332.doi:10.1111/febs.14985.PMC6852297.PMID31287944.

- ^Mura M, Swain RK, Zhuang X, Vorschmitt H, Reynolds G, Durant S, Beesley JF, Herbert JM, Sheldon H, Andre M, Sanderson S, Glen K, Luu NT, McGettrick HM, Antczak P, Falciani F, Nash GB, Nagy ZS, Bicknell R (January 2012)."Identification and angiogenic role of the novel tumor endothelial marker CLEC14A".Oncogene.31(3): 293–305.doi:10.1038/onc.2011.233.PMID21706054.

- ^McKearn JP, Baum C, Davie JM (January 1984)."Cell surface antigens expressed by subsets of pre-B cells and B cells".Journal of Immunology.132(1): 332–9.doi:10.4049/jimmunol.132.1.332.PMID6606670.S2CID27256762.

- ^Zekavat G, Mozaffari R, Arias VJ, Rostami SY, Badkerhanian A, Tenner AJ, Nichols KE, Naji A, Noorchashm H (June 2010)."A novel CD93 polymorphism in non-obese diabetic (NOD) and NZB/W F1 mice is linked to a CD4+ iNKT cell deficient state".Immunogenetics.62(6): 397–407.doi:10.1007/s00251-010-0442-3.PMC2875467.PMID20387063.

- ^McGreal EP, Ikewaki N, Akatsu H, Morgan BP, Gasque P (May 2002)."Human C1qRp is identical with CD93 and the mNI-11 antigen but does not bind C1q".Journal of Immunology.168(10): 5222–32.doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5222.PMID11994479.

- ^Dieterich LC, Mellberg S, Langenkamp E, Zhang L, Zieba A, Salomäki H, Teichert M, Huang H, Edqvist PH, Kraus T, Augustin HG, Olofsson T, Larsson E, Söderberg O, Molema G, Pontén F, Georgii-Hemming P, Alafuzoff I, Dimberg A (November 2012). "Transcriptional profiling of human glioblastoma vessels indicates a key role of VEGF-A and TGFβ2 in vascular abnormalization".The Journal of Pathology.228(3): 378–90.doi:10.1002/path.4072.PMID22786655.S2CID31223309.

- ^abcLangenkamp E, Zhang L, Lugano R, Huang H, Elhassan TE, Georganaki M, Bazzar W, Lööf J, Trendelenburg G, Essand M, Pontén F, Smits A, Dimberg A (November 2015)."Elevated expression of the C-type lectin CD93 in the glioblastoma vasculature regulates cytoskeletal rearrangements that enhance vessel function and reduce host survival".Cancer Research.75(21): 4504–16.doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3636.PMID26363010.

- ^abcLugano R, Vemuri K, Yu D, Bergqvist M, Smits A, Essand M, Johansson S, Dejana E, Dimberg A (August 2018)."CD93 promotes β1 integrin activation and fibronectin fibrillogenesis during tumor angiogenesis".The Journal of Clinical Investigation.128(8): 3280–3297.doi:10.1172/JCI97459.PMC6063507.PMID29763414.

Further reading

edit- Chevrier S, Genton C, Kallies A, Karnowski A, Otten LA, Malissen B, Malissen M, Botto M, Corcoran LM, Nutt SL, Acha-Orbea H (March 2009)."CD93 is required for maintenance of antibody secretion and persistence of plasma cells in the bone marrow niche".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.106(10): 3895–900.Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3895C.doi:10.1073/pnas.0809736106.PMC2656176.PMID19228948.

- Tenner AJ (August 1998). "C1q receptors: regulating specific functions of phagocytic cells".Immunobiology.199(2): 250–64.doi:10.1016/s0171-2985(98)80031-4.PMID9777410.

- Ghebrehiwet B, Peerschke EI, Hong Y, Munoz P, Gorevic PD (June 1992). "Short amino acid sequences derived from C1q receptor (C1q-R) show homology with the Alpha chains of fibronectin and vitronectin receptors and collagen type IV".Journal of Leukocyte Biology.51(6): 546–56.doi:10.1002/jlb.51.6.546.PMID1377218.S2CID1214598.

- Peerschke EI, Ghebrehiwet B (November 1990)."Platelet C1q receptor interactions with collagen- and C1q-coated surfaces".Journal of Immunology.145(9): 2984–8.doi:10.4049/jimmunol.145.9.2984.PMID2212670.S2CID25469682.

- Eggleton P, Lieu TS, Zappi EG, Sastry K, Coburn J, Zaner KS, Sontheimer RD, Capra JD, Ghebrehiwet B, Tauber AI (September 1994)."Calreticulin is released from activated neutrophils and binds to C1q and mannan-binding protein".Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology.72(3): 405–9.doi:10.1006/clin.1994.1160.PMID8062452.

- Joseph K, Ghebrehiwet B, Peerschke EI, Reid KB, Kaplan AP (August 1996)."Identification of the zinc-dependent endothelial cell binding protein for high molecular weight kininogen and factor XII: identity with the receptor that binds to the globular" heads "of C1q (gC1q-R)".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.93(16): 8552–7.Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.8552J.doi:10.1073/pnas.93.16.8552.PMC38710.PMID8710908.

- Cáceres J, Brandan E (May 1997). "Interaction between Alzheimer's disease beta A4 precursor protein (APP) and the extracellular matrix: evidence for the participation of heparan sulfate proteoglycans".Journal of Cellular Biochemistry.65(2): 145–58.doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(199705)65:2<145::AID-JCB2>3.0.CO;2-U.PMID9136074.S2CID43911847.

- Nepomuceno RR, Tenner AJ (February 1998)."C1qRP, the C1q receptor that enhances phagocytosis, is detected specifically in human cells of myeloid lineage, endothelial cells, and platelets".Journal of Immunology.160(4): 1929–35.doi:10.4049/jimmunol.160.4.1929.PMID9469455.S2CID25486549.

- Stuart GR, Lynch NJ, Day AJ, Schwaeble WJ, Sim RB (December 1997). "The C1q and collectin binding site within C1q receptor (cell surface calreticulin)".Immunopharmacology.38(1–2): 73–80.doi:10.1016/S0162-3109(97)00076-3.PMID9476117.

- Nepomuceno RR, Ruiz S, Park M, Tenner AJ (March 1999)."C1qRP is a heavily O-glycosylated cell surface protein involved in the regulation of phagocytic activity".Journal of Immunology.162(6): 3583–9.doi:10.4049/jimmunol.162.6.3583.PMID10092817.S2CID22415546.

- Norsworthy PJ, Taylor PR, Walport MJ, Botto M (August 1999). "Cloning of the mouse homolog of the 126-kDa human C1q/MBL/SP-A receptor, C1qR(p)".Mammalian Genome.10(8): 789–93.doi:10.1007/s003359901093.PMID10430665.S2CID2160211.

- Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA (November 2000)."DNA cloning using in vitro site-specific recombination".Genome Research.10(11): 1788–95.doi:10.1101/gr.143000.PMC310948.PMID11076863.

- Kittlesen DJ, Chianese-Bullock KA, Yao ZQ, Braciale TJ, Hahn YS (November 2000)."Interaction between complement receptor gC1qR and hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits T-lymphocyte proliferation".The Journal of Clinical Investigation.106(10): 1239–49.doi:10.1172/JCI10323.PMC381434.PMID11086025.

- Joseph K, Shibayama Y, Ghebrehiwet B, Kaplan AP (January 2001). "Factor XII-dependent contact activation on endothelial cells and binding proteins gC1qR and cytokeratin 1".Thrombosis and Haemostasis.85(1): 119–24.doi:10.1055/s-0037-1612914.PMID11204562.S2CID35432595.

- Simpson JC, Wellenreuther R, Poustka A, Pepperkok R, Wiemann S (September 2000)."Systematic subcellular localization of novel proteins identified by large-scale cDNA sequencing".EMBO Reports.1(3): 287–92.doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvd058.PMC1083732.PMID11256614.

- Steinberger P, Szekeres A, Wille S, Stöckl J, Selenko N, Prager E, Staffler G, Madic O, Stockinger H, Knapp W (January 2002). "Identification of human CD93 as the phagocytic C1q receptor (C1qRp) by expression cloning".Journal of Leukocyte Biology.71(1): 133–40.doi:10.1189/jlb.71.1.133.PMID11781389.S2CID31767877.

External links

edit- CD93+protein,+humanat the U.S. National Library of MedicineMedical Subject Headings(MeSH)

- HumanCD93genome location andCD93gene details page in theUCSC Genome Browser.