Thedot-com bubble(ordot-com boom) was astock market bubblethat ballooned during the late-1990s and peaked on Friday, March 10, 2000. This period of market growth coincided with the widespread adoption of theWorld Wide Weband theInternet,resulting in a dispensation of availableventure capitaland the rapid growth of valuations in new dot-comstartups.

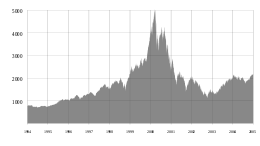

Between 1995 and its peak in March 2000, investments in the NASDAQ composite stock market index rose by 800%, only to fall to 78% from its peak by October 2002, giving up all its gains during the bubble.

During thedot-com crash,manyonline shoppingcompanies, notablyPets,Webvan,andBoo,as well as several communication companies, such asWorldcom,NorthPoint Communications,andGlobal Crossing,failed and shut down.[1][2]Others, likeLastminute,MP3andPeopleSoundremained through its sale and buyers acquisition. Larger companies likeAmazonandCisco Systemslost large portions of their market capitalization, with Cisco losing 80% of its stock value.[2][3]

Background

editHistorically, the dot-com boom can be seen as similar to a number of other technology-inspired booms of the past, includingrailroadsin the 1840s, automobiles in the early 20th century,radioin the 1920s,televisionin the 1940s,transistorelectronics in the 1950s, computer time-sharing in the 1960s, andhome computersandbiotechnologyin the 1980s.[4]

Overview

editLow interest rates in 1998–99 facilitated an increase in start-up companies.

In 2000, the dot-com bubble burst, and many dot-com startups went out of business after burning through theirventure capitaland failing to becomeprofitable.[5]However, many others, particularly online retailers likeeBayandAmazon,blossomed and became highly profitable.[6][7]More conventional retailers found online merchandising to be a profitable additional source of revenue. While some online entertainment and news outlets failed when their seed capital ran out, others persisted and eventually became economically self-sufficient. Traditional media outlets (newspaper publishers, broadcasters and cablecasters in particular) also found the Web to be a useful and profitable additional channel for content distribution, and an additional means to generate advertising revenue. The sites that survived and eventually prospered after the bubble burst had two things in common: a sound business plan, and a niche in the marketplace that was, if not unique, particularly well-defined and well-served.

In the aftermath of the dot-com bubble, telecommunications companies had a great deal of overcapacity as many Internet business clients went bust. That, plus ongoing investment in local cell infrastructure kept connectivity charges low, and helped to make high-speed Internet connectivity more affordable.[citation needed]During this time, a handful of companies found success developing business models that helped make the World Wide Web a more compelling experience. These include airline booking sites,Google'ssearch engineand its profitable approach to keyword-based advertising,[8]as well aseBay's auction site[6]andAmazon's online department store.[7]The low price of reaching millions worldwide, and the possibility of selling to or hearing from those people at the same moment when they were reached, promised to overturn established business dogma in advertising,mail-ordersales,customer relationship management,and many more areas. The web was a newkiller app—it could bring together unrelated buyers and sellers in seamless and low-cost ways. Entrepreneurs around the world developed new business models, and ran to their nearestventure capitalist.[9]While some of the new entrepreneurs had experience in business and economics, the majority were simply people with ideas, and did not manage the capital influx prudently. Additionally, many dot-com business plans were predicated on the assumption that by using the Internet, they would bypass the distribution channels of existing businesses and therefore not have to compete with them; when the established businesses with strong existing brands developed their own Internet presence, these hopes were shattered, and the newcomers were left attempting to break into markets dominated by larger, more established businesses.[10]

The dot-com bubble burst in March 2000, with the technology heavyNASDAQ Compositeindex peaking at 5,048.62 on March 10[11](5,132.52 intraday), more than double its value just a year before. By 2001, the bubble's deflation was running full speed. A majority of the dot-coms had ceased trading, after having burnt through their venture capital and IPO capital, often without ever making a profit. But despite this, the Internet continues to grow, driven by commerce, ever greater amounts of online information, knowledge,social networkingand access by mobile devices.

Prelude to the bubble

editThe 1993 release ofMosaicand subsequentweb browsersduring the following years gave computer users access to theWorld Wide Web,popularizing use of the Internet.[12]Internet use increased as a result of the reduction of the "digital divide"and advances in connectivity, uses of the Internet, and computer education. Between 1990 and 1997, the percentage of households in the United States owning computers increased from 15% to 35% as computer ownership progressed from a luxury to a necessity.[13]This marked the shift to theInformation Age,an economy based oninformation technology,and many new companies were founded.

At the same time, a decline in interest rates increased the availability of capital.[14]TheTaxpayer Relief Act of 1997,which lowered the top marginalcapital gains tax in the United States,also made people more willing to make more speculative investments.[15]Alan Greenspan,then-Chair of the Federal Reserve,allegedly fueled investments in the stock market by putting a positive spin on stock valuations.[16]TheTelecommunications Act of 1996was expected to result in many new technologies from which many people wanted to profit.[17]

The bubble

editAs a result of these factors, many investors were eager to invest, at any valuation, in anydot-com company,especially if it had one of theInternet-related prefixesor a ""suffixin its name.Venture capitalwas easy to raise.Investment banks,which profited significantly frominitial public offerings(IPO), fueled speculation and encouraged investment in technology.[18]A combination of rapidly increasing stock prices in thequaternary sector of the economyand confidence that the companies would turn future profits created an environment in which many investors were willing to overlook traditional metrics, such as theprice–earnings ratio,and base confidence on technological advancements, leading to astock market bubble.[16]Between 1995 and 2000, the Nasdaq Composite stock market index rose 400%. It reached a price–earnings ratio of 200, dwarfing the peak price–earnings ratio of 80 for the JapaneseNikkei 225during theJapanese asset price bubbleof 1991.[16]In 1999, shares ofQualcommrose in value by 2,619%, 12 other large-cap stocks each rose over 1,000% in value, and seven additional large-cap stocks each rose over 900% in value. Even though the Nasdaq Composite rose 85.6% and theS&P 500rose 19.5% in 1999, more stocks fell in value than rose in value as investors sold stocks in slower growing companies to invest in Internet stocks.[19]

An unprecedented amount of personal investing occurred during the boom and stories of people quitting their jobs to trade on the financial market were common.[20]Thenews mediatook advantage of the public's desire to invest in the stock market; an article inThe Wall Street Journalsuggested that investors "re-think" the "quaint idea" of profits,[21]andCNBCreported on the stock market with the same level of suspense as many networks provided to thebroadcasting of sports events.[16][22]

At the height of the boom, it was possible for a promising dot-com company to become apublic companyvia an IPO and raise a substantial amount of money even if it had never made a profit—or, in some cases, realized any material revenue. People who receivedemployee stock optionsbecame instant paper millionaires when their companies executed IPOs; however, most employees were barred from selling shares immediately due tolock-up periods.[18][page needed]The most successful entrepreneurs, such asMark Cuban,sold their shares or entered intohedgesto protect their gains.Sir John Templetonsuccessfullyshortedmany dot-com stocks at the peak of the bubble during what he called "temporary insanity" and a "once-in-a-lifetime opportunity". He shorted stocks just before the expiration of lockup periods ending six months after initial public offerings, correctly anticipating many dot-com company executives would sell shares as soon as possible, and that large-scale selling would force down share prices.[23][24]

Spending tendencies of dot-com companies

editMost dot-com companies incurrednet operating lossesas they spent heavily on advertising and promotions to harnessnetwork effectsto buildmarket shareormind shareas fast as possible, using the mottos "get big fast" and "get large or get lost". These companies offered their services or products for free or at a discount with the expectation that they could build enoughbrand awarenessto charge profitable rates for their services in the future.[25][26]

The "growth over profits" mentality and the aura of "new economy"invincibility led some companies to engage in lavish spending on elaborate business facilities and luxury vacations for employees. Upon the launch of a new product or website, a company would organize an expensive event called adot-com party.[27][28]

Bubble in telecom

editIn the five years after the AmericanTelecommunications Act of 1996went into effect,telecommunications equipmentcompanies invested more than $500 billion, mostly financed with debt, into laying fiber optic cable, adding new switches, and building wireless networks.[17]In many areas, such as theDulles Technology Corridorin Virginia, governments funded technology infrastructure and created favorable business and tax law to encourage companies to expand.[29]The growth in capacity vastly outstripped the growth in demand.[17]Spectrum auctionsfor3Gin the United Kingdom in April 2000, led byChancellor of the ExchequerGordon Brown,raised £22.5 billion.[30]In Germany, in August 2000, the auctions raised £30 billion.[31][32]A 3Gspectrum auctionin the United States in 1999 had to be re-run when the winners defaulted on their bids of $4 billion. The re-auction netted 10% of the original sales prices.[33][34]When financing became hard to find as the bubble burst, the highdebt ratiosof these companies led tobankruptcy.[35]Bond investors recovered just over 20% of their investments.[36]However, several telecom executives sold stock before the crash includingPhilip Anschutz,who reaped $1.9 billion,Joseph Nacchio,who reaped $248 million, andGary Winnick,who sold $748 million worth of shares.[37]

Bursting the bubble

editNearing the turn of the 2000s, spending on technology was volatile as companies prepared for theYear 2000 problem.There were concerns that computer systems would have trouble changing their clock and calendar systems from 1999 to 2000 which might trigger wider social or economic problems, but there was virtually no impact or disruption due to adequate preparation.[38]Spending on marketing also reached new heights for the sector: Two dot-com companies purchased ad spots forSuper Bowl XXXIII,and 17 dot-com companies bought ad spots the following year forSuper Bowl XXXIV.[39]

On January 10, 2000,America Online,led bySteve CaseandTed Leonsis,announced amergerwithTime Warner,led byGerald M. Levin.The merger was the largest to date and was questioned by many analysts.[40]Then, on January 30, 2000, 12 ads of the 61 ads forSuper Bowl XXXIVwere purchased by dot-coms (sources state ranges from 12 up to 19 companies depending on the definition ofdot-com company). At that time, the cost for a 30-second commercial was between $1.9 million and $2.2 million.[41][42]

Meanwhile,Alan Greenspan,thenChair of the Federal Reserve,raised interest rates several times; these actions were believed by many to have caused the bursting of the dot-com bubble. According toPaul Krugman,however, "he didn't raise interest rates to curb the market's enthusiasm; he didn't even seek to impose margin requirements on stock market investors. Instead, [it is alleged] he waited until the bubble burst, as it did in 2000, then tried to clean up the mess afterward".[43]Finance author and commentatorE. Ray Canterberyagreed with Krugman's criticism.[44]

On Friday March 10, 2000, the NASDAQ Composite stock market index peaked at 5,048.62.[45]However, on March 13, 2000, news thatJapanhad once again entered arecessiontriggered a global sell off that disproportionately affected technology stocks.[46]Soon after,Yahoo!andeBayended merger talks and the Nasdaq fell 2.6%, but theS&P 500rose 2.4% as investors shifted from strong performing technology stocks to poor performing established stocks.[47]

On March 20, 2000,Barron'sfeatured a cover article titled "Burning Up; Warning: Internet companies are running out of cash—fast", which predicted the imminent bankruptcy of many Internet companies.[48]This led many people to rethink their investments. That same day,MicroStrategyannounced a revenue restatement due to aggressive accounting practices. Its stock price, which had risen from $7 per share to as high as $333 per share in a year, fell $140 per share, or 62%, in a day.[49]The next day, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates, leading to aninverted yield curve,although stocks rallied temporarily.[50]

Tangentially to all of speculation, JudgeThomas Penfield Jacksonissued his conclusions of law in the case ofUnited States v. Microsoft Corp.(2001)and ruled that Microsoft was guilty ofmonopolizationandtyingin violation of theSherman Antitrust Act.This led to a one-day 15% decline in the value of shares in Microsoft and a 350-point, or 8%, drop in the value of the Nasdaq. Many people saw the legal actions as bad for technology in general.[51]That same day,Bloomberg Newspublished a widely read article that stated: "It's time, at last, to pay attention to the numbers".[52]

On Friday, April 14, 2000, the Nasdaq Composite index fell 9%, ending a week in which it fell 25%. Investors were forced to sell stocks ahead ofTax Day,the due date to pay taxes on gains realized in the previous year.[53]By June 2000, dot-com companies were forced to reevaluate their spending on advertising campaigns.[54]On November 9, 2000,Pets,a much-hyped company that had backing from Amazon, went out of business only nine months after completing its IPO.[55][56]By that time, most Internet stocks had declined in value by 75% from their highs, wiping out $1.755 trillion in value.[57]In January 2001, just three dot-com companies bought advertising spots duringSuper Bowl XXXV.[58]TheSeptember 11 attacksaccelerated the stock-market drop.[59]Investor confidence was further eroded by severalaccounting scandalsand the resulting bankruptcies, including theEnron scandalin October 2001, theWorldCom scandalin June 2002,[60]and theAdelphia Communications Corporationscandal in July 2002.[61]

By the end of thestock market downturn of 2002,stocks had lost $5 trillion inmarket capitalizationsince the peak.[62]At its trough on October 9, 2002, the NASDAQ-100 had dropped to 1,114, down 78% from its peak.[63][64]

Aftermath

editAfter venture capital was no longer available, the operational mentality of executives and investors completely changed. A dot-com company's lifespan was measured by itsburn rate,the rate at which it spent its existing capital. Many dot-com companies ran out of capital and went throughliquidation.Supporting industries, such as advertising and shipping, scaled back their operations as demand for services fell. However, many companies were able to endure the crash; 48% of dot-com companies survived through 2004, albeit at lower valuations.[25]

Several companies and their executives, includingBernard Ebbers,Jeffrey Skilling,andKenneth Lay,were accused or convicted offraudfor misusing shareholders' money, and theU.S. Securities and Exchange Commissionlevied large fines against investment firms includingCitigroupandMerrill Lynchfor misleading investors.[65]

After suffering losses, retail investors transitioned their investment portfolios to more cautious positions.[66]PopularInternet forumsthat focused onhigh techstocks, such asSilicon Investor,Yahoo! Finance,andThe Motley Fooldeclined in use significantly.[67]

Job market and office equipment glut

editLayoffs ofprogrammersresulted in ageneral glutin the job market. University enrollment for computer-related degrees dropped noticeably.[68][69]Aeron chairs,which retailed for $1,100 each, were liquidated en masse.[70]

Legacy

editAs growth in the technology sector stabilized, companies consolidated; some, such asAmazon,eBay,NvidiaandGooglegained market share and came to dominate their respective fields. The most valuable public companies are now generally in the technology sector.

In a 2015 book, venture capitalistFred Wilson,who funded many dot-com companies and lost 90% of his net worth when the bubble burst, said about the dot-com bubble:

A friend of mine has a great line. He says "Nothing important has ever been built withoutirrational exuberance."Meaning that you need some of this mania to cause investors to open up their pocketbooks and finance the building of the railroads or the automobile or aerospace industry or whatever. And in this case, much of the capital invested was lost, but also much of it was invested in a very highthroughputbackbone for the Internet, and lots of software that works, and databases and server structure. All that stuff has allowed what we have today, which has changed all our lives... that's what all this speculative mania built.[71]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^"The greatest defunct Web sites and dotcom disasters".CNET.June 5, 2008.Archivedfrom the original on August 28, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^abKumar, Rajesh (December 5, 2015).Valuation: Theories and Concepts.Elsevier.p. 25.

- ^Powell, Jamie (2021-03-08)."Investors should not dismiss Cisco's dot com collapse as a historical anomaly".Financial Times.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-12-10.Retrieved2022-04-06.

- ^Edwards, Jim (December 6, 2016)."One of the kings of the '90s dot-com bubble now faces 20 years in prison".Business Insider.Archivedfrom the original on October 11, 2018.RetrievedOctober 11,2018.

- ^A revealing look at the dot-com bubble of 2000 — and how it shapes our lives today | (ted )

- ^ab‘Wallets and eyeballs’: how eBay turned the internet into a marketplace | eBay | The Guardian

- ^abHow Amazon Survived the Dot-Com Bubble | HBS Online

- ^The new dot com bubble is here: it’s called online advertising – The Correspondent

- ^Where Are They Now: 17 Dot-Com Bubble Companies And Their Founders (cbinsights )

- ^The Dotcom Bubble Burst (2000) (internationalbanker )

- ^"Nasdaq peak of 5,048.62".Archivedfrom the original on 2017-11-11.Retrieved2022-04-15.

- ^Kline, Greg (April 20, 2003)."Mosaic started Web rush, Internet boom".The News-Gazette.Archivedfrom the original on June 13, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^"Issues in labor Statistics"(PDF).U.S. Department of Labor.1999.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2017-05-12.Retrieved2017-04-14.

- ^Weinberger, Matt (February 3, 2016)."If you're too young to remember the insanity of the dot-com bubble, check out these pictures".Business Insider.Archivedfrom the original on March 13, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^"Here's Why The Dot Com Bubble Began And Why It Popped".Business Insider.December 15, 2010.Archivedfrom the original on April 6, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^abcdTeeter, Preston; Sandberg, Jorgen (2017). "Cracking the Enigma of asset bubbles with narratives".Strategic Organization.15(1): 91–99.doi:10.1177/1476127016629880.S2CID156163200.

- ^abcLitan, Robert E. (December 1, 2002)."The Telecommunications Crash: What To Do Now?".Brookings Institution.Archivedfrom the original on March 30, 2018.RetrievedMarch 30,2018.

- ^abSmith, Andrew(2012).Totally Wired: On the Trail of the Great Dotcom Swindle.Bloomsbury Books.ISBN978-1-84737-449-3.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-01.Retrieved2017-05-08.

- ^Norris, Floyd(January 3, 2000)."THE YEAR IN THE MARKETS; 1999: Extraordinary Winners and More Losers".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on August 31, 2017.RetrievedAugust 26,2017.

- ^Kadlec, Daniel (August 9, 1999)."Day Trading: It's a Brutal World".Time.Archivedfrom the original on April 15, 2017.RetrievedApril 14,2017.

- ^Wysocki, Bernard (May 19, 1999)."Companies Chose to Rethink A Quaint Concept: Profits".The Wall Street Journal.Archivedfrom the original on August 8, 2021.RetrievedAugust 8,2021.

- ^Lowenstein, Roger(2004).Origins of the Crash: The Great Bubble and Its Undoing.Penguin Books.p.115.ISBN978-1-59420-003-8.

- ^Langlois, Shawn (May 9, 2019)."John Templeton profited from 'temporary insanity' in 2000 — now it's your turn, says longtime money manager".MarketWatch.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-07-31.Retrieved2021-04-03.

- ^"Old Dog, New Tricks".Forbes.May 28, 2001.Archivedfrom the original on March 7, 2021.RetrievedApril 3,2021.

- ^abBERLIN, LESLIE (November 21, 2008)."Lessons of Survival, From the Dot-Com Attic".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on September 6, 2017.RetrievedAugust 26,2017.

- ^Dodge, John (May 16, 2000)."MotherNature 's CEO Defends Dot-Coms' Get-Big-Fast Strategy".The Wall Street Journal.Archivedfrom the original on April 15, 2017.RetrievedApril 14,2017.

- ^Cave, Damien (April 25, 2000)."Dot-com party madness".Salon.Archivedfrom the original on March 9, 2018.RetrievedMarch 8,2018.

- ^HuffStutter, P.J. (December 25, 2000)."Dot-Com Parties Dry Up".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on June 13, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^Donnelly, Sally B.; Zagorin, Adam (August 14, 2000)."D.C. Dotcom".Time.Archivedfrom the original on June 7, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^"UK mobile phone auction nets billions".BBC News.April 27, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on August 23, 2017.RetrievedJune 7,2020.

- ^Osborn, Andrew (November 17, 2000)."Consumers pay the price in 3G auction".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on June 7, 2020.RetrievedJune 7,2020.

- ^"German phone auction ends".CNN.August 17, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on June 7, 2020.RetrievedJune 7,2020.

- ^Keegan, Victor (April 13, 2000)."Dial-a-fortune".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on February 5, 2021.RetrievedJune 7,2020.

- ^Sukumar, R. (April 11, 2012)."Policy lessons from the 3G failure".Mint.Archivedfrom the original on June 7, 2020.RetrievedJune 7,2020.

- ^White, Dominic (December 30, 2002)."Telecoms crash 'like the South Sea Bubble'".The Daily Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on June 7, 2020.RetrievedJune 7,2020.

- ^Hunn, David; Eaton, Collin (September 12, 2016)."Oil bust on par with telecom crash of dot-com era".Houston Chronicle.Archivedfrom the original on June 7, 2020.RetrievedJune 7,2020.

- ^"Inside the Telecom Game".Bloomberg Businessweek.August 5, 2002.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-06-07.Retrieved2020-06-07.

- ^Marsha Walton;Miles O'Brien(1 January 2000)."Preparation pays off; world reports only tiny Y2K glitches".CNN.Archived fromthe originalon 7 December 2004.

- ^Beer, Jeff (2020-01-20)."20 years ago, the dot-coms took over the Super Bowl".Fast Company.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-03-02.Retrieved2020-03-02.

- ^Johnson, Tom (January 10, 2000)."Thats AOL folks".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on December 11, 2017.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^Pender, Kathleen (September 13, 2000)."Dot-Com Super Bowl Advertisers Fumble / But Down Under, LifeMinders may win at Olympics".San Francisco Chronicle.Archivedfrom the original on March 2, 2020.RetrievedMarch 2,2020.

- ^Kircher, Madison Malone (February 3, 2019)."Revisiting the Ads From 2000's 'Dot-Com Super Bowl'".New York.Archivedfrom the original on March 2, 2020.RetrievedMarch 2,2020.

- ^Krugman, Paul(2009).The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008.W.W. Norton. p.142.ISBN978-0-393-33780-8.

- ^Canterbery, E. Ray (2013).The Global Great Recession.World Scientific. pp. 123–135.ISBN978-981-4322-76-8.

- ^Long, Tony (March 10, 2010)."March 10, 2000: Pop Goes the Nasdaq!".Wired.Archivedfrom the original on March 8, 2018.RetrievedMarch 8,2018.

- ^"Nasdaq tumbles on Japan".CNN.March 13, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on October 30, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^"Dow wows Wall Street".CNN.March 15, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on October 30, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^Willoughby, Jack (March 10, 2010)."Burning Up; Warning: Internet companies are running out of cash—fast".Barron's.Archivedfrom the original on March 30, 2018.RetrievedMarch 30,2018.

- ^"MicroStrategy plummets".CNN.March 20, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on October 11, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^"Wall St.: What rate hike?".CNN.March 21, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on October 11, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^"Nasdaq sinks 350 points".CNN.April 3, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on August 11, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^Yang, Catherine (April 3, 2000)."Commentary: Earth To Dot Com Accountants".Bloomberg News.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-05-25.Retrieved2017-05-04.

- ^"Bleak Friday on Wall Street".CNN.April 14, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on November 27, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^Owens, Jennifer (June 19, 2000)."IQ News: Dot-Coms Re-Evaluate Ad Spending Habits".AdWeek.Archivedfrom the original on May 25, 2017.

- ^"Pets at its tail end".CNN.November 7, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on July 27, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^"The Pets Phenomenon".MSNBC.October 19, 2016.Archivedfrom the original on June 12, 2018.RetrievedJune 28,2018.

- ^Kleinbard, David (November 9, 2000)."The $1.7 trillion dot lesson".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on October 24, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^Elliott, Stuart (January 8, 2001)."In Super Commercial Bowl XXXV, the not-coms are beating the dot-coms".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on August 31, 2017.RetrievedAugust 26,2017.

- ^"World markets shatter".CNN.September 11, 2001.Archivedfrom the original on September 20, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^Beltran, Luisa (July 22, 2002)."WorldCom files largest bankruptcy ever".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on October 30, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2018.

- ^"SEC Charges Adelphia and Rigas Family With Massive Financial Fraud".sec.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 2010-11-09.Retrieved2021-04-18.

- ^Gaither, Chris; Chmielewski, Dawn C. (July 16, 2006)."Fears of Dot-Com Crash, Version 2.0".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on December 18, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^Glassman, James K. (February 11, 2015)."3 Lessons for Investors From the Tech Bubble".Kiplinger's Personal Finance.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-04-04.Retrieved2020-02-10.

- ^Alden, Chris (March 10, 2005)."Looking back on the crash".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on January 4, 2018.RetrievedMarch 30,2018.

- ^"Ex-WorldCom CEO Ebbers found guilty on all counts – Mar. 15, 2005".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-07-03.Retrieved2021-06-20.

- ^Reuteman, Rob (August 9, 2010)."Hard Times Investing: For Some, Cash Is Everything And Only Thing".CNBC.Archivedfrom the original on May 25, 2017.RetrievedSeptember 9,2017.

- ^Forster, Stacy (January 31, 2001)."Raging Bull Goes for a Bargain As Interest in Stock Chat Wanes".The Wall Street Journal.Archivedfrom the original on December 9, 2018.RetrievedDecember 9,2018.

- ^desJardins, Marie (October 22, 2015)."The real reason U.S. students lag behind in computer science".Fortune.Archivedfrom the original on March 7, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^Mann, Amar; Nunes, Tony (2009)."After the Dot-Com Bubble: Silicon Valley High-Tech Employment And Wages in 2001 and 2008".Bureau of Labor Statistics.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-11-16.Retrieved2017-04-14.

- ^Kennedy, Brian (September 15, 2006)."Remembering the Dot-Com Throne".New York.Archivedfrom the original on June 6, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2020.

- ^Donnelly, Jacob (February 14, 2016)."Here's what the future of bitcoin looks like—and it's bright".VentureBeat.Archivedfrom the original on April 15, 2017.RetrievedApril 14,2017.

Further reading

edit- Abramson, Bruce (2005).Digital Phoenix; Why the Information Economy Collapsed and How it Will Rise Again.MIT Press.ISBN978-0-262-51196-4.

- Aharon, David Y.; Gavious, Ilanit; Yosef, Rami (2010). "Stock market bubble effects on mergers and acquisitions".The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance.50(4): 456–70.doi:10.1016/j.qref.2010.05.002.

- Cassidy, John (2009).Dot.con: How America Lost Its Mind and Its Money in the Internet Era.HarperCollins.ISBN9780061841781.

- Cellan-Jones, Rory (2001).Dot.Bomb: The Rise and Fall of Dot Britain.Aurum.ISBN978-1854107909.

- Daisey, Mike (2014).Twenty-one Dog Years: Doing Time at Amazon.Free Press.ISBN978-0-7432-2580-9.

- Goldfarb, Brent D.; Kirsch, David; Miller, David A. (April 24, 2006). "Was There Too Little Entry During the Dot Com Era?".Robert H. Smith School Research Paper(RHS 06-029).SSRN899100.

- Kindleberger, Charles P. (2005).Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises.John Wiley & Sons.ISBN9780230365353.[permanent dead link]

- Kuo, David(2001).dot.bomb: My Days and Nights at an Internet Goliath.Little, Brown.ISBN978-0-316-60005-7.

- Lowenstein, Roger(2004).Origins of the Crash: The Great Bubble and Its Undoing.Penguin Books.ISBN978-1-59420-003-8.

- Wolff, Michael(1999).Burn Rate: How I Survived the Gold Rush Years on the Internet.Orion Publishing Group.ISBN9780752826066.Burn RateatGoogle Books.