East Los Angeles(Spanish:Este de Los Ángeles), orEast L.A.,is anunincorporated areasituated withinLos Angeles County, California,United States. According to theUnited States Census Bureau,East Los Angeles is designated as acensus-designated place(CDP) for statistical purposes. The most recent data from the2020 censusreports a population of 118,786, reflecting a 6.1% decrease compared to the2010population of 126,496.[3]

East Los Angeles, California | |

|---|---|

Images, from top and left to right: East LA Public Library, Civic Center Park,Atlantic E Line Station | |

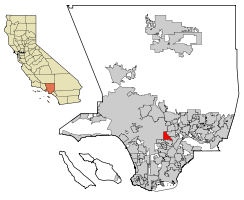

Location of East Los Angeles inLos Angeles County, California | |

| Coordinates:34°2′N118°10′W/ 34.033°N 118.167°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Los Angeles |

| Area | |

• Total | 7.46 sq mi (19.31 km2) |

| • Land | 7.45 sq mi (19.30 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) 0.06% |

| Elevation | 200 ft (61 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 118,786 |

| • Density | 15,938.01/sq mi (6,153.58/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8(PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7(PDT) |

| ZIP code | 90022, 90063 |

| Area code(s) | 213 and 323 |

| FIPS code | 06-20802 |

| GNISfeature ID | 1660583[2] |

Theconcentration of Hispanic/Latino Americansis 95.16 percent, the highest of any city or census-designated place in the United States outside ofPuerto Rico.[4]

History

editOriginal East Los Angeles

editHistorically, when it was founded in 1873, the neighborhood northeast of downtown known today asLincoln Heightswas originally named East Los Angeles, but in 1917, residents voted to change the name to its present name. Today, it is considered part ofEastside Los Angeles,the geographic region east of theLos Angeles Riverthat includes three neighborhoods within the city of Los Angeles (Boyle Heights,El Sereno,and Lincoln Heights) and the unincorporated community in Los Angeles County known today as "East Los Angeles". Lincoln Heights is 4 miles (6 km) northwest of present-day East Los Angeles. When Lincoln Heights, the first Eastside subdivision created in 1873, changed its name in 1917, Belvedere (Belvedere Gardens and Belvedere Heights) and surrounding unincorporated county areas were given the moniker of East Los Angeles. By the 1930s, most maps had started to label the Belvedere area as "East Los Angeles".

Belvedere

editThe cornerstone of the first building ofOccidental Collegewas laid in September 1887 on Rowan Street.[5]In 1896, the building was destroyed by fire.[5]

On April 2, 1905, it was reported that theJanss Investment Companywould be developing an area "on Boyle Heights" (later,Boyle Heightswould refer only to a smaller area to the west, i.e. the neighborhood now called Boyle Heights within the Los Angeles city limits). The 170-acre (0.69 km2) tract was located at the eastern terminus of theLos Angeles Railway's"R" streetcar line. Originally known as "Hazard's Eastside Extension", was to be namedHighland Villa,[6]but would later be rechristenedBelvedere Heights.[7][8]Belvedere Heights, at its launch in 1905, extended from the L.A. city limits (Indiana Av.) on the west to Rowan Av. on the east, from Aliso St. on the south to Wabash Av. on the north, the northwestern portion of today's East Los Angeles,[6]thus including the lower portions of what today is calledCity Terrace.

By the early 1920s, workers in the sprouting industrial district to the south were seeking nearby housing. At the time, the unincorporated region was undeveloped and or preserved foragricultureandoil extraction.[9]Belvedere township included the territory that in 1902 became the city ofMontebello.[10]

By 1922 Janss advertised that it had sold 6000 lots there and that 35,000 people lived in Belvedere Heights. Buildings that were described as being in Belvedere Heights included the junior high school on Record between Brooklyn and Michigan, now called Belvedere Middle School.[11]

In February 1921 Janss announced that it had purchased 150 acres (61 ha) adjacent to the end of the streetcar line on Stephenson Avenue, nowWhittier Boulevard,south of Belvedere Heights, and divided the empty land into housing lots of square-milegrid cells.[12]Janss called the new tractBelvedere Gardens,[11]an area still found today on maps for the area east of theLong Beach Freeway.[13]

The area was able to avoid being annexed into the City of Los Angeles because of a private groundwater utility formed in 1926 now known as theCalifornia Water Service,which would later become a customer of theMetropolitan Water District.Prior to the passage ofProposition 13in 1978, governing bodies would set property taxes independently, which led to a cumulative overlapping rate including bond taxes for large infrastructure projects such as the building of the Port of Los Angeles. However, unincorporated areas were often forced to incorporate or be annexed into these ta xing entities in order to obtain critical municipal services such as water from the Los Angeles Aqueduct. For decades, the lack of a city property tax and bond taxes made East Los Angeles a tax haven for the working class.

New name: East Los Angeles

editIn 1932 local business leaders gave the name East Los Angeles to Belvedere and adjacent areas (that had been known as Belvedere Gardens, Belvedere Heights, Laguna, etc.) However, in 1937 the Automobile Club of Southern California put up three large signs, "Belvedere Gardens". This led to the business leaders uprooting the signs, with a "burial ceremony" for the signs with 150 state, county, and city officials attending, and they rechristeed the area East Los Angeles. Several county buildings were renamed in line with the new appellation. At that time the area had 75,000 residents and was "declared to be the largest unincorporated locality in the world."[14]

East Los Angeles was a significant site during theChicano Movement,which included theEast L.A. Walkoutsin 1968 and the NationalChicano Moratorium,in whichRuben Salazarwas killed.[15][16]

Multiple campaigns by residents have been made forcityhoodfor East Los Angeles, such as in 2010.[17]

Geography

editEast L.A. is located immediately east of theBoyle Heightsdistrict of Los Angeles, south of theEl Serenodistrict of Los Angeles, north of the city ofCommerce,and west of the cities ofMonterey ParkandMontebello.

The unincorporated area known asCity Terrace[18]occupies the northern part of the CDP. The Census Bureau definition of the area may not precisely correspond to the local understanding of the community.

Climate

editEast L.A. has a very warmhot-summer Mediterranean climate.

| Climate data for East Los Angeles, California (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

74 (23) |

76 (24) |

80 (27) |

83 (28) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

83 (28) |

77 (25) |

73 (23) |

81 (27) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 48 (9) |

48 (9) |

51 (11) |

53 (12) |

57 (14) |

61 (16) |

65 (18) |

65 (18) |

63 (17) |

58 (14) |

52 (11) |

47 (8) |

56 (13) |

| Averageprecipitationinches (mm) | 3.78 (96) |

3.53 (90) |

2.66 (68) |

0.93 (24) |

0.33 (8.4) |

0.06 (1.5) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.18 (4.6) |

0.30 (7.6) |

1.21 (31) |

2.43 (62) |

16.43 (417) |

| Source:[19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editEast Los Angeles is the least ethnically diverse community inLos Angeles County,as noted by theLos Angeles Times'"Mapping L.A."survey.Mexican(85.4%) andItalian(0.2%) are the most common ancestries.MexicoandEl Salvadorwere the most common foreign places of birth.[20]

2010

editThe2010 United States Census[21]reported that East Los Angeles had a population of 126,496.Population densitywas 16,973.5 people per square mile (6,553.5 people/km2). The racial makeup of East Los Angeles was 53,934 (50.5%)White(1.5% Non-Hispanic White),[22]817 (0.6%)African American,1,549 (1.2%)Native American,1,144 (0.9%)Asian,63 (0.0%)Pacific Islander,54,846 (43.4%) fromother races,and 4,143 (4.3%) from two or more races.HispanicorLatinoof any race were 122,784 persons (97.1%).

The Census reported that 126,176 people (99.7% of the population) lived in households, 174 (0.1%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 146 (0.1%) were institutionalized.

There were 30,816 households, out of which 17,509 (56.8%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 15,497 (50.3%) wereopposite-sex married couplesliving together, 7,104 (23.1%) had a female householder with no husband present, 3,238 (10.5%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 2,516 (8.2%)unmarried opposite-sex partnerships,and 199 (0.6%)same-sex married couples or partnerships.3,781 households (12.3%) were made up of individuals, and 1,781 (5.8%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.09. There were 25,839families(83.8% of all households); the average family size was 4.33.

The population was spread out, with 39,804 people (31.5%) under the age of 18, 15,193 people (12.0%) aged 18 to 24, 37,354 people (29.5%) aged 25 to 44, 23,281 people (18.4%) aged 45 to 64, and 10,864 people (8.6%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.1 males.

There were 32,201 housing units at an average density of 4,320.8 units per square mile (1,668.3 units/km2), of which 10,986 (35.7%) were owner-occupied, and 19,830 (64.3%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.2%; the rental vacancy rate was 3.2%. 47,123 people (37.3% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 79,053 people (62.5%) lived in rental housing units.

According to the 2010 United States Census, East Los Angeles had a median household income of $37,982, with 26.9% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[22]

2000

editAs of 2000,[23]there were 124,283 people, 29,844 households, and 25,068 families residing in the community. The population density was 16,697.4 inhabitants per square mile (6,446.9/km2). There were 31,096 housing units at an average density of 4,177.8 units per square mile (1,613.1 units/km2). The racial makeup of the community was 39.3%White,4.52%BlackorAfrican American,1.29%Native American,0.77%Asian,0.06%Pacific Islander,54.01% fromother races,and 4.22% from two or more races. 96.8% of the population wereHispanicorLatino.

As of 2000, speakers ofSpanishas afirst languageaccounted for 87.30%, whileEnglishaccounted for 12.65%,Japanesewas spoken by 0.16%,Armenianmade up 0.09%,Vietnamesewas at 0.07%,Chineseat 0.05%,Russianat 0.04%,Tagalogat 0.03%, andMandarinwas at 0.03% of the population.[24]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 104,270 | — | |

| 1970 | 104,881 | 0.6% | |

| 1980 | 110,017 | 4.9% | |

| 1990 | 126,379 | 14.9% | |

| 2000 | 124,283 | −1.7% | |

| 2010 | 126,496 | 1.8% | |

| 2020 | 118,786 | −6.1% | |

| [25][26] | |||

There were 29,844 households, out of which 51.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.1% were married couples living together, 21.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 16.0% were non-families. 12.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.15 and the average family size was 4.42.

The age distribution of the community was as follows: 34.6% under the age of 18, 12.6% from 18 to 24, 30.7% from 25 to 44, 14.2% from 45 to 64, and 7.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 26 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 99.2 males.

The median income for a household in the community was $28,544, and the median income for a family was $29,755. Males had a median income of $21,065 versus $18,475 for females. Theper capita incomefor the community was $9,543. About 24.7% of families and 27.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 35.0% of those under age 18 and 13.5% of those age 65 or over. East Los Angeles has a very large Latino population that consists of Mexicans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Nicaraguans.

Latino communities These were the tencitiesorneighborhoodsin Los Angeles County with the largest percentage ofLatino residents,according to the 2000 census:[27]

- East Los Angeles, California,96.7%

- Maywood, California,96.4%

- City Terrace, California,94.4%

- Huntington Park, California,95.1%

- Boyle Heights, Los Angeles,94.0%

- Cudahy, California,93.8%

- Bell Gardens, California,93.7%

- Commerce, California93.4%

- Vernon, California,92.6%

- South Gate, California,92.1%

Homelessness

editIn 2022,Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority's Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count counted 617 homeless individuals in East Los Angeles.[28]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 231 | — |

| 2017 | 461 | +99.6% |

| 2018 | 343 | −25.6% |

| 2019 | 604 | +76.1% |

| 2020 | 550 | −8.9% |

| 2022 | 617 | +12.2% |

| Source:Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority | ||

Government

editIn theUnited States House of Representativeshouse, East Los Angeles is in theCalifornia's 34th congressional districtdistrict served byJimmy Gomez.

At theCalifornia State Legislature,East Los Angeles is inthe 26th Senate District,represented byDemocratMaría Elena Durazo,and inthe 52nd Assembly District,represented byDemocratWendy Carrillo.[29]

As East Los Angeles is an unincorporated community, it does not have a local government and relies on the County of Los Angeles for local services. SupervisorHilda L. Solisrepresents East LA on theBoard of Supervisors.

The East Los Angelescounty hallhouses theLos Angeles County Department of Public Works- East Los Angeles Building And Safety Office.[30]

Since East Los Angeles is an unincorporated area, fire protection in East Los Angeles is provided by theLos Angeles County Fire Departmentwith ambulance transport byCare Ambulance Service.

TheLos Angeles County Sheriff's Department(LASD) operates the East Los Angeles Station in East Los Angeles.[31]

TheLos Angeles County Department of Health Servicesoperates the Central Health Center inDowntown Los Angeles,serving East Los Angeles.[32]

TheUnited States Postal ServiceEast Los Angeles Post Office is located at 975 SouthAtlantic Boulevard.[33]

Transportation

editLight railservice to East L.A. is provided by theE Line's Eastside Extension, which opened in 2009 as the Gold Line. The E Line train is not the first light rail line to travel to East LA. In the early 1900s, people needing to access the cemeteries on the east side took the streetcar, the Stephenson Avenue Line. Stephenson Avenue (before 1920) now known as Whittier Boulevard. In time factories needed a better road to move their goods south. Stephenson Avenue was public choice. Historian Matt Roth of theAuto Clubsays Whittier Boulevard is the main thoroughfare through the east side. "The City Council renamed it Whittier Boulevard in 1921," he says, "out of recognition that it was serving an inter-regional function because it was the main road to Whittier and beyond."[34]Into the 1960sUnion PacificChicago-bound passenger trains made stops in East Los Angeles.[35]

TheLos Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority(Metro) providesbusservice from East L.A. throughout the L.A. area. A Metro Customer Center is located at 4501 B Whittier Blvd.[36]Local shuttle service is provided byEl Sol(the East Los Angeles Shuttle).

The Metro AtlanticParking Structureis a paid daily on-site parking with 238 spaces and paid reserved on-site parking 24 spaces supporting the E Line.[37]Bike rackSpaces and bike lockers also support most E Line stations.

Education

editPrimary and secondary schools

editPublic schools

editEast Los Angeles is split betweenLos Angeles Unified School DistrictandMontebello Unified School District.[38][39]LAUSD operates Amanecer PC in East Los Angeles, which is apreschool.[40]

LAUSDelementary schoolsin East Los Angeles include Anton, Belvedere, Brooklyn Avenue, City Terrace, Eastman, Fourth Street, Ford Boulevard (open July 1, 1923), Harrison, Humphreys Avenue Elementary School andSTEMMagnetSchool (open July 1, 1922), Robert F. Kennedy, Marianna, Rowan Avenue and Hamasaki Elementarymedicalandsciencemagnet,originally named Riggin Elementary School and renamed in 1990.[41][39]Montebello USD schools include Gascon Elementary School, Montebello Park Elementary School, and Winter Gardens Elementary School.[39]At one time Hammel Elementary School was in East Los Angeles.[42]

Middle schoolsinclude Belvedere and GriffithSTEAMMagnet.[39]In 2017, a petition was started to remove the nameD. W. Griffithfrom the East Los Angeles middle school because his 1915 filmThe Birth of a Nationcelebrated theKu Klux Klan.[43][39]Griffith who also co-producedThe Life of General Villa,abiographicalaction–drama film starringPancho Villaas himself, shot on location in Mexico during theMexican Revolution.[44]

James A. Garfield High SchoolandComputer ScienceMagnet is the sole traditional LAUSD publichigh schoolin East Los Angeles.[39]Garfield High School opened its doors in 1925, grades 7 through 12. It was a six-year school in which one could earn two diplomas, one from Garfield Junior High School after completion of 9th grade and one from Garfield Senior High School. By the late 1930s, Garfield became overcrowded and a new Junior High School for grades 7 through 9 was built, Kern Avenue Junior High School, located on Fourth Street and Kern Avenue, now called Griffith STEAM Magnet Middle School.[45]Garfield High School participates in the "East LA Classic"againstTheodore Roosevelt High Schoolafootballgame that traditionally draws over 25,000 fans.[46]Ramona Opportunity High School, an alternative allgirl public high school,is in East Los Angeles serving grades 7-12.[47]Esteban Torres High Schoolopened in 2010 on the former Hammel Street Elementary School grounds and in former housing developments. There are five autonomous pilot high schools located on theEsteban E. TorresHigh School campus, part of the Los Angeles Education Partnership's network of partner and community schools.[42][48][49]Monterey High School, a continuation high school, serves the needs of at-risk students in the East Los Angeles community.

In 2013 adult education programs from theEastside Learning CenterandEast Los Angeles Occupational Centerrelocated at theEast Los Angeles Star Hospitalsite to form an adult learning center and high school academy. The modified 1929, three-story structure houses theHilda L. Solis Learning Academy School of Technology, Business and Education(STBE) high school andEast LA Star Adult Education[50][51]

East Los Angeles College(ELAC) was part of unincorporated East Los Angeles before it was annexed by Monterey Park in the early 1970s.

Charter schools

editOther schools in the area include theKnowledge Is Power Program(KIPP)charter schoolsRaíces Academy (GradesTransitional kindergarten(TK)-4), Iluminar Academy (Grades TK-4), Sol Academy (Grades 5-8), Academy of Innovation (Grades 5-8).[52]The KIPP is a nationwide network of free open-enrollment college-preparatory schools. The Arts in Action Community Charter Elementary School (Grades TK-5) open and started classes at its new school site in the 2019–2020 school year.[53]

Five middle schools that include in 2014 the ÁnimoEllen OchoaCharter Middle School was founded and named after formerastronautand Director of theJohnson Space Center.The Alliance College-Ready Middle Academy 8 opened August 1, 2014.[54]The Arts in Action Charter Middle school opened in summer 2020.

Construction of a new Ednovate Charter High School to be named Esperanza College Prep was started in October 2021. Expected to be ready by fall 2022. Once completed, about 440 Esperanza students currently split between Hilda Solis Learning Academy and the former Our Lady of Soledad (Our Lady of Solitude) School will be taught under one roof. A performance space and adance studiowill allow aBaile Folkloricodance program to practice.[55]The Alliance Morgan McKinzie High School opened August 31, 2009.[56]TheOscar De La Hoya Ánimo Charter High Schoolwas temporary in the Salesian Boys and Girls Club of Los Angeles before it moved to it new location in Boyle Heights (it opened its doors in August 2003).

Private schools

editTheRoman Catholic Archdiocese of Los AngelesoperatesCatholicprivate schoolsin the CDP.[39]Schools includeOur Lady of LourdesSchool (July 1, 1980 K-8),[57]St. AlphonsusSchool (July 1, 1980 K-8),[58]andOur Lady of GuadalupeSchool (July 1, 1980 K-8).[59]

Public libraries

editEast Los Angeles

editTheCounty of Los Angeles Public Libraryoperates the East Los Angeles Library.[39][60]The East Los Angeles Library opened on May 1, 1923; originally it was a collection of books in a store. A building was built to house the collection several months later. A new library building opened in 1924. In 1932 the library moved to a new building. In 1967 the library moved into another building, which was 15,120 square feet (1,405 m2) large. In 2004 the library moved to its current location, a 26,300 square feet (2,440 m2) facility designed by Stephen Finney of theGlendalefirm CWA AIA, Inc. The current library has areas for adults and children, theChicanoResource Center (CRC) established in 1976, a 175-person meeting room, a computer room, a Friends of the Library bookstore, and free parking areas. The library design hasMayandesign and themes, as requested from area residents. References to the sun and moon, which are themes in Mayan art, were incorporated in the library.[60]

Anthony Quinn

editThe county operates theAnthony QuinnLibrary with amoderne architecture,originally known as the Belvedere Library, which opened in January 1914. In 1925 the library moved to a storefront facility; at that time its collection was several thousand books. In 1937 the library moved to a new site. In 1973 the library moved to its current location. On January 5, 1982, the library took its current name; the childhood house of actor Anthony Quinn was located on the present day site of the library, and the library was renamed after Quinn. In 1987, Quinn donated his collection of movie scripts, scrapbooks, and personal papers to the library name after him.[61]The First Supervisorial District funded a renovation that occurred in 2000. The library reopened in February 2001 with a new appearance and new furnishings.[39][62]

Other

editThe county operates the El Camino Real Library at 5,529 sq ft. with a meeting room capacity 45.[39][63]The library opened in 1929 as the Stephenson Library. In 1972 the library moved to its current location, and in 1975 it was rededicated as the El Camino Real library, as it is located on the historicEl Camino Real.[63]The library was rededicated again in November 2014 after a renovation and expansion that added ameeting room,teen area, and outdoor reading patio.[64] The county operates the City Terrace Library. The library has been in its current location since 1979 and refurbished in 2009.[39][65][66]

Notable places

editOur Lady of Solitude

editOur Lady of Solitude,known as Soledad Church, opened its doors onChristmas Dayin 1925. Located in the neighborhood now known as Old Town Maravilla. The church was constructed inSpanish Colonial Revivalarchitecture. In December 1931, the Church held its first outdoor procession in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe, a ritual that continues today. The GuadalupeProcessionis the oldest religious procession in Los Angeles.[67]

Starting in the 1960s, labor leaderCesar Chavezand members of theUnited Farm Workersmet with the Claretian priests, who also became activists, in the church's basement. The street in front of the church is known asCesar Chavez Avenue.In October 1993, theLos Angeles City Counciland theCounty Board of Supervisorsapproved the renaming of the stretch of roadway, but agreed to delay the change until 1994 and to put up historic plaques along Brooklyn Avenue to accommodate the opposition,[68]many of whom believed that the new name would cause people to forget theJewish history of the area.In 1979, the tile-cladcupolaandbell towerwere removed due to termite damage, and thebellswere reinstalled near the church entrance.[69]

The Golden Gate Theater

editThe formerGolden Gate Theatermovie palace aSpanish Baroque RevivalChurrigueresque-style building built in 1927, is one of fewer than two dozen buildings in Los Angeles in the Spanish Churrigueresque style and one of a few remaining in southern California. The Golden Gate Theater is the first East Los Angeles building listed in theNational Register of Historic Placesin 1982.[70]

Maravilla Handball Court and El Centro Grocery

editCompleted in 1928 the Maravillahandballcourt was built brick-by-brick by residents, with the El Centro Grocery and residence added in 1946. The oldest remaining handball court in the Los Angeles region. In the early 1940s, Michi and Tommy Nishiyama operated the property and in the 1950s following Michi's internment at aJapanese relocation camp.The only court in East Los Angeles where players still playedbola basca,also known asBasque pelota.[71]In 2012, the Maravilla handball court and grocery store were put on theCalifornia Register of Historical Resources.[72]

Veterans memorial

editThe obelisk-shaped monument at Atlantic Park was dedicated on May 30, 1930, during a Memorial Day Parade that ended at what was then called Belvedere Gardens Park. A plaque on the monument reads, "In memory of heroes of all American wars".[73]

Latino Walk of Fame

editThe Walk of Fame is similar to the one inHollywoodbut with a focus onLatinocelebrities. The Latino Walk of Fame was inaugurated on April 30, 1997, to honor outstanding leaders who have made historical and social contributions with a Sun Plaque on Whittier Boulevard the heart of East L.A. Spaces have been created for over 280 plaques. Permanent granite plaques have been put in place for the first 20 honorees. The merchants’ association of East Los Angeles sponsors a comprehensive clean-up campaign that cleans the sidewalks and gutters daily and removes litter and trash.[74][75]Though the Latino Walk of Fame is there, it seems to go unnoticed, "The Latino Walk of Fame had a good run once it started...".

El Pino

editEl Pino (The Pine Tree)is a largebunya pinelocated on the southeastern corner of Folsom Street and N. Indiana Street overlooking the Wellington Heights neighborhood of East Los Angeles and the Boyle Heights from atop a small hill.[76]The people of East Los Angeles consider the tree aliving monumentof the area's multifaceted ethnic background.[77]The tree has become a symbol of community resistance to thegentrificationof their neighborhood.[77][78]

Parks and recreation

editLos Angeles County operates parks and recreation in East Los Angeles.

Built in 1942 and originally known as Soledad Park, the 39.1-acre (15.8 ha) Belvedere Community Regional Park has a baseball diamond and picnic area that was upgrade in the 1980s, basketball courts, a playground, community center, fitness zone, gymnasium, skate park, soccer field, splash pad, an Olympic-size swimming pool, and tennis courts.[39][79]The park was renamed in 1949 and has aVernacular architecturestyle. The LA county constructed a courthouse and sheriff's station on the south end of Belvedere Park in the mid-1950s. Then more buildings were added in time, in conjunction with the East Los Angeles Library, turning the southern end of the park into in effect a civic center. The construction of thePomona Freeway(I-60) in the 1960s cut through the park, dividing it into two connected by a bridge. In the late 1960s the county also constructed a pond (Belvedere Lake) in the southern area of the park, known to locals as "El Parque de los Patos" (The duck park). The park is a popular place for festivals and host musicians, artisans, fishing and other events in its lakeside amphitheater. TheCalifornia Department of Fish and Wildlifesupplies the lake withrainbow troutduring the Winter through early Spring andcatfishduring the Summer. There are also somelargemouth bass,carpandbluegillin the lake.[80]On August 29, 1970, Belvedere Park was the starting point of theChicano Moratorium.An estimated 30,000 people marched from Belvedere Park to Laguna Park (now Salazar Park). In the 1990s the northern region of the part was revitalized.[81]

Atlantic Avenue Park has a children's play area, picnic, and barbecue areas, a men's locker room, a women's locker room, and a 50-meter, six-lane swimming pool. In addition, the park has a rose garden maintained by volunteers.[82]

Eugene A. Obregon Park is named afterEugene A. Obregon,a veteran andMedal of Honorrecipient. The park's official opening was on May 26, 1966. The park includes basketball courts, ceramic rooms, a community room, a computer center, a fitness zone, a gymnasium, a multi-purpose field, a swimming pool, and a walking path.[39][83]

The 8.4-acre (3.4 ha)Salazar Parkis within East Los Angeles and has amoderne architecture.The county purchased the original 1.47 acres (0.59 ha) of park property fromCedars of Lebanon Hospitalon March 8, 1938. The land was officially designated as the "East Los Angeles Playground" two months later. On June 25, 1940, the property was renamed the "Laguna Park and Playground." On September 17, 1970, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors gave the park its current name. The park includes a baseball diamond, basketball courts, a children's play area, a community room, a computer center, a gymnasium, picnic shelters, a senior center, a swimming pool, and tennis courts.[39][84]On August 29, 2014, the County dedicated a plaque at the site in honor of Ruben Salazar.[85]

The 4.8-acre (1.9 ha) Saybrook Park is also in East Los Angeles. The County Board of Supervisors approved final plans for developing the park on May 1, 1973. The park includes two outdoor basketball courts, a ball diamond, children's play areas, a community building with a community room, a computer technology building with a computer room, picnic and barbecue areas, and a tennis court.[39][86]

City Terrace County Park was developed in 1933 byWorks Progress Administrationcrews; the park occupied a piece of 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) terrace that was formed after crews hacked a rugged and barren hill. In 1957 600,000 cubic yards (460,000 m3) of soil that had been removed from the construction of theLos Angeles Civic Centerwas transported to the City Terrace County Park. The soil filled a ravine, tripling the park's original acreage. The park has a basketball court, a children's playground, a community room, a computer center, a gymnasium, a multi-purpose field, a swimming pool, and tennis courts.[39][87]

The Eastside Eddie Heredia Bo xing Club, operated by the county, is inside a former fire station. The club was named after Eddie Heredia, the first club champion, who died of leukemia at age 17. One of the members of the Heredia club became a member of the United States Olympic Bo xing Team and entered the2008 Beijing Olympics.[39][88]

Notable people

edit- Roberto Esteban Chavez,artist, muralist

- Julian NavaUnited States Ambassador to Mexico and prominent educator

- Gary Clarke,American actor best known for his role as Steve Hill

- Oscar De La Hoya,world bo xing champion and 1992 Olympic gold medalist,[89][90]born toMexican migrant farmworkerparents[91]: 101

- Jaime Escalante,educator, subject of the filmStand and Deliver[92]

- Seniesa Estrada,world bo xing champion[93]

- Dorothy Granada,nurse, humanitarian, and peace and social justice activist who was raised in East Los Angeles and won theInternational Pfeffer Peace Awardin 1997[94]

- Suzanna Guzmán,mezzo soprano,an original associate artists ofLos Angeles Opera

- Antonia Hernandez,philanthropist, attorney, activist

- Sam Johnson,American football player[95]

- Patrick Kearney,serial killer, rapist, and necrophile[96]

- Constance Marie,actress[97]

- Carlos Mencia,comedian[90]

- Xavier Montelongo,professional boxer[98]

- Carlos Montes,Chicano activist and co-founder of theBrown Berets[99]

- Sergio Mora,boxer[100]

- Edward James Olmos,actor, producer, and director[101]

- Dan Peña,financial analystonWall Street

- Anthony Quinn,actor

- Luis J. Rodriguez,writer and activist[102]

- Lucille Roybal-Allard,U.S. Representative[103]

- Hope Sandoval,singer and songwriter[104]

- Jesse Valadez,owner of the famouslowriderGypsy Rose

- Linda Vallejois an American artist known for painting, sculpture and ceramics.

- Antonio Villaraigosa,41st mayor of Los Angeles

- Maria Helena Viramontes,writer and professor[105][106]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^"2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files".United States Census Bureau.RetrievedOctober 30,2021.

- ^"East Los Angeles".Geographic Names Information System.United States Geological Survey,United States Department of the Interior.

- ^"Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), East Los Angeles CDP, California".American FactFinder.U.S. Census Bureau. Archived fromthe originalon February 13, 2020.RetrievedSeptember 4,2019.

- ^"P2: HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE".2020 Census.United States Census Bureau.Archivedfrom the original on October 16, 2021.RetrievedOctober 10,2021.

- ^abMurphy, William S. (April 20, 1987)."Occidental College: A Lively Center of Learning Turns 100".Los Angeles Times.RetrievedMarch 29,2015.

- ^ab"Broad Acres To Be Platted; Janss Investment Company Makes Big Purchase".Los Angeles Herald. April 2, 1905. p. 3.RetrievedJuly 4,2024.

- ^Spitzzeri, Paul R. (September 25, 1911)."Getting Schooled at Belvedere School, East Los Angeles, 25 September 1911".homestead museum.RetrievedAugust 18,2019.

- ^Hernandez, Kim. "The Bungalow Boom".Southern California Quarterly:376.

- ^"Who Moved East L.A.?".RetrievedAugust 8,2019.

- ^"About Belvedere".RetrievedAugust 8,2019.

- ^ab"Janss Company Celebrates Twenty-First Birthday".Los Angeles Evening Express. April 15, 1922.

- ^"Open Little Farm Home Tract on City Car Line".Los Angeles Evening Express. February 23, 1921.

- ^"Belvedere Gardens", Google Maps, accessed October 16, 2020

- ^"Belvedere drops name: East Los Angeles Conducts Burial for District's Old Title".Los Angeles Times.September 11, 1937. p. 6.

- ^Suderburg, Erika (2000).Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art.University of Minnesota Press. p. 191.ISBN9780816631599.

- ^Sahagun, Louis."Know your East L.A. history. A day of rage and racist neglect".Los Angeles Times.RetrievedJanuary 27,2023.

- ^"Cityhood for East Los Angeles".cityhoodforeastla.org.Archived fromthe originalon November 10, 2010.RetrievedNovember 22,2010.

- ^Bureau, U.S. Census."American FactFinder - Search".factfinder.census.gov.Archived fromthe originalon February 16, 2020.RetrievedApril 9,2018.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^"Average Weather for East Los Angeles, CA - Temperature and Precipitation".weather.RetrievedMay 3,2014.

- ^"Diversity Ranking - Mapping L.A. - Los Angeles Times".maps.latimes.RetrievedMay 3,2014.

- ^"2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - East Los Angeles CDP".U.S. Census Bureau. Archived fromthe originalon July 15, 2014.RetrievedJuly 12,2014.

- ^ab"East Los Angeles CDP QuickFacts".US Census Bureau.2014. Archived fromthe originalon August 10, 2012.RetrievedJuly 29,2014.

- ^"American FactFinder".factfinder.census.gov.RetrievedMay 3,2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^"MLA Data Center Results for East Los Angeles, California".Modern Language Association.RetrievedNovember 19,2007.

- ^"California: Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990".US Bureau of the Census.1997.RetrievedJuly 29,2014.

- ^"American FactFinder".US Census Bureau.[dead link]

- ^"Latino" Mapping L.A.,Los Angeles Times

- ^"Homeless Count by City/Community".LAHSA.RetrievedApril 14,2023.

- ^"Statewide Database".Regents of the University of California.RetrievedMay 7,2015.

- ^"East Los Angeles Building And Safety Office".RetrievedAugust 11,2019.

- ^"East Los Angeles StationArchived2010-01-25 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department.Retrieved on January 21, 2010.

- ^"Central Health Center."Los Angeles County Department of Health Services.Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^"Post Office Location - EAST LOS ANGELESArchived2009-02-10 at theWayback Machine."United States Postal Service.Retrieved on December 6, 2008.

- ^"Stephenson Avenue".89.3 KPCC Member-supported news for Southern California Street Stories. November 21, 2009. Archived fromthe originalon August 19, 2019.RetrievedAugust 19,2019.

- ^Union Pacific April 12, 1964, Tables A, E, O, R

- ^"Customer Centers".metro.net.

- ^"Atlantic Parking Structure".metro.net. Archived fromthe originalon October 23, 2019.RetrievedAugust 11,2019.

- ^"Los Angeles Unified School District: Education K-12".Unincorporated Area East Los Angeles.2013. Archived fromthe originalon July 10, 2012.RetrievedJuly 29,2014.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopq"East Los Angeles CDP, California".U.S. Census Bureau.Archived fromthe originalon June 6, 2011.RetrievedMarch 15,2010.

- ^"Amanecer PCArchived2011-03-21 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles Unified School District.Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"Elementary School Named for Deceased Principal".Los Angeles Times.February 15, 1990. Archived fromthe originalon June 4, 2011.RetrievedMarch 15,2010.

Renamed: an East Los Angeles elementary school in honor of its popular principal,... Riggin Elementary School will become Morris K. Hamasaki Elementary.

- ^abDiMassa, Cara Mia. "Los Angeles; Accord Reached on High School for East L.A.; Proposal aims to ease the enrollment burden at Garfield. It involves building on the site of an elementary campus.ArchivedOctober 25, 2012, at theWayback Machine"Los Angeles Times.May 22, 2004. California Metro, Part B, Metro Desk. B3. Retrieved on March 15, 2010. "building the school on the site of what is now Hammel Street Elementary."

- ^Home pageArchivedDecember 3, 2016, at theWayback Machine."la school report. Retrieved on March 09, 2017.

- ^"D.W. Griffith: Hollywood Independent".Cobbles. June 26, 1917.RetrievedJune 5,2011.

- ^"Garfield Junior High School Comes to a Close".James A Garfield Senior High School.

- ^"Weingart Stadium at East Los Angeles College".lasports.org.Archived fromthe originalon June 22, 2006.RetrievedJuly 29,2019.

- ^"Ramona High SchoolArchived2011-03-21 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles Unified School District./ Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"Project Details".laschools.org.RetrievedMay 3,2014.

- ^Merl, Jean. "Los Angeles; District Seeks Space for Charter Campuses, Eastside High School; L.A. Unified acts to provide land for charter sites under state law. Marchers demand a new campus for the East L.A. area.ArchivedOctober 25, 2012, at theWayback Machine"Los Angeles Times.March 31, 2004. California Metro, Part B, Metro Desk. B3. Retrieved on March 15, 2010. "next-best site for a 2000-student high school: Hammel Street Elementary and some adjacent housing in East Los Angeles. The grade school would be moved."

- ^"Project Details".csdadesigngroup. April 12, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 8,2019.

- ^"LAUSD Offcials[sic] Cut the Ribbon on the Hilda L. Solis Learning Academy".home.lausd.net.

- ^"KIPP Elementary & Middle Schools".RetrievedAugust 11,2019.

- ^"ARTS IN ACTION COMMUNITY CHARTER SCHOOLS".RetrievedJuly 28,2019.

- ^"Alliance College-Ready Middle Academy 8".RetrievedAugust 11,2019.

- ^Rodriguez, Monica."East L.A. makes room for new charter school campus Esperanza College Prep".The Eastsider la.RetrievedMay 18,2022.

- ^"Alliance Morgan McKinzie High School".RetrievedAugust 11,2019.

- ^"Our Lady of Lourdes LA[permanent dead link]."Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles.Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"Home".saintalphonsusschool.org.

- ^"Our Lady of Guadalupe LA[permanent dead link]."Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles.Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^ab"East Los Angeles LibraryArchived2010-01-26 at theWayback Machine."County of Los Angeles Public Library.Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"Anthony Quinn Library overview".laconservancy.org.June 26, 2018.RetrievedAugust 4,2019.

- ^"Anthony Quinn Library."County of Los Angeles Public Library.Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^ab"El Camino Real LibraryArchived2010-01-26 at theWayback Machine."County of Los Angeles Public Library.Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"El Camino Real library COMMUNITY tab Library History."County of Los Angeles Public Library.Retrieved on August 10, 2019.

- ^"City Terrace LibraryArchived2010-07-03 at theWayback Machine."County of Los Angeles Public Library.Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"City Terrace Library - County of Los Angeles Public Library".colapublib.org.Archived fromthe originalon April 25, 2018.RetrievedAugust 10,2019.

- ^"Annual Our Lady of Guadalupe Procession Archdiocese honors Our Lady of Guadalupe".la-archdiocese.org.RetrievedAugust 16,2019.

- ^"Cesar Chavez Avenue Gets OK After Concessions To Critics Of Site."Los Angeles Times.Oct. 14, 1993. p. B 3.

- ^"Our Lady of Solitude".laconservancy.org.RetrievedAugust 16,2019.

- ^"William and Clifford Balch".laconservancy.org.RetrievedAugust 3,2019.

- ^"Maravilla Handball Court and El Centro Grocery".laconservancy.org.RetrievedAugust 3,2019.

- ^"Japanese American Heritage".laconservancy.org.RetrievedAugust 3,2019.

- ^Salgado, C. J. (May 23, 2019)."Neglected East L.A. veterans monument once again commanding attention".The Eastsider.theeastsiderla.RetrievedFebruary 20,2021.

- ^"Exploring East Los Angeles".amoeba.RetrievedAugust 3,2019.

- ^"The Latino Walk Of Fame".highschool.latimes. May 4, 2016.RetrievedAugust 3,2019.

- ^Arellano, Gustavo (January 1, 2021)."Column: People came by to pay final respects to this East L.A. tree that went Hollywood. Too soon?".Los Angeles Times.RetrievedJanuary 17,2024.

- ^abZornosa, Laura (March 2, 2021)."Why East L.A. community members still worry about the future of a beloved tree".Los Angeles Times.RetrievedNovember 28,2021.

- ^Vives, Ruben (July 18, 2017)."A community in flux: Will Boyle Heights be ruined by one coffee shop?".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on October 9, 2017.RetrievedOctober 11,2017.

- ^"Belvedere Community Regional Park."Los Angeles County. Retrieved on August 09, 2019.

- ^"[1]"BELVEDERE PARK LAKE Retrieved on August 9, 2019.

- ^"[2]."Belvedere Park. Retrieved on August 5, 2019.

- ^"Atlantic Avenue ParkArchived2011-07-25 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles County. Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"Eugene A. Obregon ParkArchived2011-07-21 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles County. Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"Ruben Salazar ParkArchived2011-07-21 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles County. Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"[3]."laconservancy. Retrieved on August 06, 2019.

- ^"Saybrook County ParkArchived2011-07-21 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles County. Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"City Terrace County ParkArchived2011-07-25 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles County. Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"Eastside Eddie Heredia Bo xing ClubArchived2011-07-25 at theWayback Machine."Los Angeles County. Retrieved on March 15, 2010.

- ^"Barcelona 1992: De La Hoya".olympic.org.RetrievedDecember 20,2013.

- ^abRivera, Carla. "East L.A.'s loss is personal."Los Angeles Times.May 22, 2007. p.1.Retrieved on March 29, 2014. "Its alumni include an array of politicians, actors, comedians, musicians, artists and sports figures, including comic Carlos Mencia and boxer Oscar De La Hoya."

- ^Overmyer, Mark (2008).Latino America: A State-by-State Encyclopedia.Westport, Conn.,US:Bloomsbury Publishing.pp. xxiii&957.ISBN978-1-57356-980-4.OCLC428815591.ISBN9780313341168.

- ^"Obituaries".Los Angeles Times.April 26, 2013.RetrievedFebruary 19,2021.

- ^Arum, Bob [@BobArum](November 7, 2022)."Bob Arum"(Tweet) – viaTwitter.

- ^Malikoff, Marina. "Work in Nicaragua lauded: Ex-Santa Cruz resident wins Pfeffer Prize."Santa Cruz, California:Santa Cruz Sentinel,April 12, 1998, front page (subscription required).

- ^"Sam Johnson Statistics on JustSportsStats".justsportsstats.

- ^"PATRICK WAYNE KEARNEY (1939- Serial Killer".June 12, 2015.

- ^"Constance Marie".IMDb.RetrievedSeptember 20,2017.

- ^"Xavier Montelongo Jr. Closes Out Amateur Career!".

- ^"Carlos Montes oral history interview conducted by David P. Cline in Alhambra, California, 2016 June 27".Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.RetrievedMay 14,2023.

- ^"Sergio Mora - Boxrec Bo xing Encyclopaedia".Boxrec.

- ^"Biography".Edward James Olmos.RetrievedSeptember 4,2019.

- ^"Luis J. Rodriguez".Poetry Foundation.RetrievedOctober 19,2020.

...grew up in the San Gabriel Valley of East Los Angeles

- ^"Biography".Office of Congresswoman Lucille Roybal-Allard.United States House of Representatives.RetrievedDecember 20,2013.

- ^"Bio".Hope Sandoval's official website.RetrievedDecember 20,2013.

- ^"Helena Viramontes, Professor, Graduate Faculty Member".cornell.edu.RetrievedDecember 20,2013.

- ^Arellano, Gustavo."The Sad Fate of East LA's Forgotten Walk of Fame".Los Angeles Times.RetrievedDecember 12,2023.