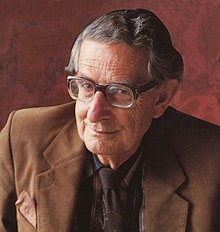

Hans Jürgen Eysenck[1](/ˈaɪzɛŋk/EYE-zenk;4 March 1916 – 4 September 1997) was a German-born British psychologist. He is best remembered for his work onintelligenceandpersonality,although he worked on other issues in psychology.[2][3]At the time of his death, Eysenck was the most frequently cited living psychologist in thepeer-reviewedscientific journalliterature.[4]

Hans Eysenck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Hans Jürgen Eysenck 4 March 1916 |

| Died | 4 September 1997(aged 81) London, England |

| Nationality | German |

| Citizenship | British |

| Alma mater | University College London(PhD) |

| Known for | Intelligence,personality psychology,Eysenck Personality Questionnaire,differential psychology,education,psychiatry,behaviour therapy |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychology |

| Institutions | Institute of Psychiatry King's College London |

| Thesis | An experimental and statistical investigation of some factors influencing aesthetic judgment(1940) |

| Doctoral advisor | Cyril Burt |

| Doctoral students | Jeffrey Alan Gray,Donald Prell |

Eysenck's research purported to show that certain personality types had an elevated risk ofcancerandheart disease.Scholars have identified errors and suspected data manipulation in Eysenck's work, and large replications have failed to confirm the relationships that he purported to find. An enquiry on behalf ofKing's College Londonfound the papers by Eysenck coauthored withRonald Grossarth-Maticekto be "incompatible with modern clinical science",[5]with 26 of the joint papers considered "unsafe".[clarification needed][6][7][5]Fourteen papers were retracted in 2020, and over 60 statements of concern were issued by scientific journals in 2020 about publications by Eysenck.[5]David Marksand Rod Buchanan, a biographer of Eysenck, have argued that 87 publications by Eysenck should be retracted.[8][5]

During his life, Eysenck's claims aboutIQ scores and race,first published in 1971, were a significant source of controversy.[9][10]Eysenck claimed that IQ scores were influenced bygeneticdifferences betweenracial groups.Eysenck's beliefs on race have been discredited by subsequent research, and are no longer accepted as part of mainstream science.[9][10]

Life

editEysenck was born inBerlin,Germany. His mother wasSilesian-born film starHelga Molander,and his father, Eduard Anton Eysenck, was an actor and nightclub entertainer who was once voted "handsomest man on the Baltic coast". His mother was Lutheran and his father was Catholic. Eysenck was brought up by his maternal grandmother who was a Jewish convert to Catholicism. Subjected to theNuremberg laws,she was deported and died in a concentration camp.[11]: 8–11 [12]: 80 An initial move to England in the 1930s became permanent because of his opposition to theNaziparty and its persecutions. "My hatred ofHitlerand the Nazis, and all they stood for, was so overwhelming that no argument could counter it. "[11]: 40 Because of his German citizenship, he was initially unable to gain employment, and he came close to being interned during the war.[13]He received his PhD in 1940 fromUniversity College London(UCL) working in the Department of Psychology under the supervision of Professor SirCyril Burt,with whom he had a tumultuous professional relationship throughout his working life.[11]: 118–119

Eysenck was Professor of Psychology at theInstitute of Psychiatry,King's College London,from 1955 to 1983. He was a major contributor to the modern scientific theory of personality and helped find treatment for mental illnesses.[14][15]Eysenck also created and developed a distinctive dimensional model of personality structure based on empirical factor-analytic research, attempting to anchor these factors in biogenetic variation.[16]In 1981, Eysenck became a founding member of theWorld Cultural Council.[17]He was the founding editor of the international journalPersonality and Individual Differences,and wrote about 80 books and more than 1,600 journal articles.[18]With his first wife, Hans Eysenck had a sonMichael Eysenck,who is also a psychology professor. He had four children with his second wife, Sybil Eysenck: Gary, Connie, Kevin, and Darrin. Hans and Sybil Eysenck collaborated as psychologists for many years at the Institute of Psychiatry, University of London, as co-authors and researchers. Sybil Eysenck died in December 2020, and Hans Eysenck died of a brain tumour[19]in a London hospice in 1997.[20]He was an atheist.[21]

The Eysencks' home was at10 Dorchester Drive,Herne Hill, London from 1960 until their respective deaths.[22]

Views and their reception

editExamples of publications in which Eysenck's views roused controversy include (chronologically):

- A paper in the 1950s[23]concluding that available data "fail to support the hypothesis that psychotherapy facilitates recovery from neurotic disorder".

- A chapter inUses and Abuses of Psychology(1953) entitled "What is wrong with psychoanalysis".

- The Psychology of Politics(1954)

- Race, Intelligence and Education(1971) (in the US:The IQ Argument).

- Sex, Violence and the Media(1978).

- Astrology — Science or Superstition?(1982).

- Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire(1985).

- Smoking, Personality and Stress(1991).

Eysenck's attitude was summarised in his autobiographyRebel with a Cause:[11]"I always felt that a scientist owes the world only one thing, and that is the truth as he sees it. If the truth contradicts deeply held beliefs, that is too bad. Tact and diplomacy are fine in international relations, in politics, perhaps even in business; in science only one thing matters, and that is the facts." He was one of the signers of theHumanist Manifesto.[24]

The Psychology of Politics

editIn this book, Eysenck suggests that political behavior may be analysed in terms of two independent dimensions: the traditional left-right distinction, and how 'tenderminded' or 'toughminded' a person is. Eysenck suggests that the latter is a result of a person's introversion or extraversion respectively.

Colleagues critiqued the research that formed the basis of this book, on a number of grounds, including the following:

- Eysenck claims that his findings can be applied to theBritish middle classas a whole, but the people in his sample were far younger and better educated than the British middle class as a whole.

- Supporters of different parties were recruited in different ways: Communists were recruited through party branches, fascists in an unspecified manner, and supporters of other parties by giving copies of the questionnaire to his students and telling them to apply it to friends and acquaintances.

- Scores were obtained by applying the same weight to groups of different sizes. For example, the responses of 250 middle-class supporters of theLiberal Partywere given the same weight as those of 27 working-class Liberals.

- Scores were rounded without explanation, in directions that supported Eysenck's theories.[25]

Genetics, race and intelligence

editEysenck advocated a strong influence fromgeneticsandrace on IQ differences.Eysenck supportedArthur Jensen's questioning of whether variation inIQbetweenracial groupswas entirely environmental.[26][27]In opposition to this position, Eysenck was punched in the face by a protester during a talk at theLondon School of Economics.[28]Eysenck also received bomb threats and threats to kill his young children.[29]

Eysenck claimed that the media had given people the misleading impression that his views were outside the mainstream scientific consensus. Eysenck citedThe IQ Controversy, the Media and Public Policyas showing that there was majority support for all of the main contentions he had put forward, and further claimed that there was no real debate about the matter among relevant scientists.[30][31]

Regarding this controversy, in 1988 S. A. Barnett described Eysenck as a "prolific popularizer" and he exemplified Eysenck's writings on this topic with two passages from his early 1970s books:[32]

All the evidence to date suggests the... overwhelming importance of genetic factors in producing the great variety of intellectual differences which we observe in our culture, and much of the difference observed between certain racial groups.

— HJ Eysenck,Race, Intelligence and Education,1971, London: Temple Smith, p. 130

the whole course of development of a child's intellectual capabilities is largely laid down genetically, and even extreme environmental changes... have little power to alter this development. H. J. EysenckThe Inequality of Man,1973, London: Temple Smith, pp. 111–12

Barnett quotes additional criticism ofRace, Intelligence and EducationfromSandra Scarr,[32]who wrote in 1976 that Eysenck's book was "generally inflammatory"[33]and that there "is something in this book to insult almost everyone exceptWASPsand Jews. "[34]Scarr was equally critical of Eysenck's hypotheses, one of which was the supposition that slavery on plantations had selected African Americans as a less intelligent sub-sample of Africans.[35]Scarr also criticised another statement of Eysenck on the alleged significantly lower IQs of Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and Greek immigrants in the US relative to the populations in their country of origin. "Although Eysenck is careful to say that these are not established facts (because no IQ tests were given to the immigrants or nonimmigrants in question?"[35]) Scarr writes that the careful reader would conclude that "Eysenck admits that scientific evidence to date does not permit a clear choice of the genetic-differences interpretation of black inferiority on intelligence tests," whereas a "quick reading of the book, however, is sure to leave the reader believing that scientific evidence today strongly supports the conclusion that US blacks are genetically inferior to whites in IQ."[35]

Some of Eysenck's later work was funded by thePioneer Fund,an organization which promotedscientific racism.[36][37]

Cancer-prone personality

editEysenck also received funding for consultation research via the New York legal firm Jacob & Medinger, which was acting on behalf of the tobacco industry. In a talk[38]given in 1994 he mentioned that he askedReynoldsfor funding to continue research. Asked what he felt about tobacco industry lawyers being involved in selecting scientists for research projects, he said that research should be judged on its quality, not on who paid for it, adding that he had not personally profited from the funds.[39]According to the UK newspaperThe Independent,Eysenck received more than £800k in this way.[40]Eysenck conducted many studies making claims about the role of personality in cigarette smoking and disease,[41][42][43]but he also said "I have no doubt, smoking is not a healthy habit."[44]

His article "Cancer, personality and stress: Prediction and prevention"[45]very clearly defines Cancer-prone (Type C) personality. The science behind this claim has now come under public scrutiny in the 2019 King's College London enquiry (see below).

Genetics of personality

editIn 1951, Eysenck's first empirical study into thegeneticsof personality was published. It was an investigation carried out with his student and associateDonald Prell,from 1948 to 1951, in whichidentical (monozygotic) and fraternal (dizygotic) twins,ages 11 and 12, were tested for neuroticism. It is described in detail in an article published in theJournal of Mental Science.Eysenck and Prell concluded: "The factor of neuroticism is not a statistical artifact, but constitutes a biological unit which is inherited as a whole....neuroticpredisposition is to a large extent hereditarily determined."[46]

Model of personality

editThe two personality dimensionsextraversionandneuroticismwere described in his 1947 bookDimensions of Personality.It is common practice in personality psychology to refer to the dimensions by the first letters, E and N.

E and N provided a two-dimensional space to describe individual differences in behaviour. Eysenck noted how these two dimensions were similar to thefour personality typesfirst proposed by the Greek physicianGalen.

- High N and high E = Choleric type

- High N and low E = Melancholic type

- Low N and high E = Sanguine type

- Low N and low E = Phlegmatic type

The third dimension,psychoticism,was added to the model in the late 1970s, based upon collaborations between Eysenck and his wife,Sybil B. G. Eysenck.[47]

Eysenck's model attempted to provide detailed theory of the causes of personality.[48]For example, Eysenck proposed that extraversion was caused by variability in cortical arousal: "introverts are characterized by higher levels of activity than extraverts and so are chronically more cortically aroused than extraverts".[49]Similarly, Eysenck proposed that location within the neuroticism dimension was determined by individual differences in thelimbic system.[50]While it seems counterintuitive to suppose that introverts aremorearoused than extraverts, the putative effect this has on behaviour is such that the introvert seeks lower levels of stimulation. Conversely, the extravert seeks to heighten his or her arousal to a more favourable level (as predicted by theYerkes-Dodson Law) by increased activity, social engagement and other stimulation-seeking behaviours.

Comparison with other theories

editJeffrey Alan Gray,a former student of Eysenck's, developed a comprehensive alternative theoretical interpretation (calledGray's biopsychological theory of personality) of the biological and psychological data studied by Eysenck – leaning more heavily on animal and learning models. Currently, the most widely used model of personality is theBig Five model.[51][52]The purported traits in the Big Five model are as follows:

- Conscientiousness

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism

- Openness to experience

- Extraversion

Extraversion and neuroticism in the Big Five are very similar to Eysenck's traits of the same name. However, what he calls the trait of psychoticism corresponds to two traits in the Big Five model: conscientiousness and agreeableness (Goldberg & Rosalack 1994). Eysenck's personality system did not address openness to experience. He argued that his approach was a better description of personality.[53]

Psychometric scales

editEysenck's theory of personality is closely linked with the psychometric scales that he and his co-workers constructed.[54]These included the Maudsley Personality Inventory (MPI), the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI), theEysenck Personality Questionnaire(EPQ),[55]as well as the revised version (EPQ-R) and its corresponding short-form (EPQ-R-S). The Eysenck Personality Profiler (EPP) breaks down different facets of each trait considered in the model.[56]There has been some debate about whether these facets should include impulsivity as a facet ofextraversionas Eysenck declared in his early work, or ofpsychoticism,as he declared in his later work.[54]

Publication in far right-wing press

editEysenck was accused of being a supporter of political causes on the extreme right. Connecting arguments were that Eysenck had articles published in the German newspaperNational-Zeitung,[57]which called him a contributor, and inNation und Europa,and that he wrote the preface to a book by a far-right French writer named Pierre Krebs,Das unvergängliche Erbe,that was published by Krebs'Thule Seminar.LinguistSiegfried Jägerinterpreted the preface to Krebs' book as having "railed against the equality of people, presenting it as an untenable ideological doctrine." In theNational ZeitungEysenck reproachedSigmund Freudfor alleged trickiness and lack of frankness.[58][59]Other incidents that fuelled Eysenck's critics likeMichael BilligandSteven Roseinclude the appearance of Eysenck's books on the UKNational Front's list of recommended readings and an interview with Eysenck published by National Front'sBeacon(1977) and later republished in the US neo-fascistSteppingstones;a similar interview had been published a year before byNeue Anthropologie,described by Eysenck's biographer Roderick Buchanan as a "sister publication toMankind Quarterly,having similar contributors and sometimes sharing the same articles. "[60]Eysenck also wrote an introduction forRoger Pearson'sRace, Intelligence and Bias in Academe.[61]In this introduction to Pearson's book, Eysenck retorts that his critics are "the scattered troops" of theNew Left,who have adopted the "psychology of the fascists".[62]Eysenck's bookThe Inequality of Man,translated in French asL'Inegalite de l'homme,was published byGRECE's publishing house, Éditions Corpernic.[63]In 1974, Eysenck became a member of the academic advisory council ofMankind Quarterly,joining those associated with the journal in attempting to reinvent it as a more mainstream academic vehicle.[64][65]Billig asserts that in the same year Eysenck also became a member of thecomité de patronageof GRECE'sNouvelle École.[66]

Remarking on Eysenck's alleged right-wing connections, Buchanan writes: "For those looking to thoroughly demonize Eysenck, his links with far right groups revealed his true political sympathies." According to Buchanan, these harsh critics interpreted Eysenck's writings as "overtly racist". Furthermore, Buchanan writes that Eysenck's fiercest critics were convinced that Eysenck was "willfully misrepresenting a dark political agenda". Buchanan argued that "There appeared to be no hidden agenda to Hans Eysenck. He was too self-absorbed, too preoccupied with his own aspirations as a great scientist to harbor specific political aims."[64]

As Buchanan commented:

Harder to brush off was the impression that Eysenck was insensitive, even willfully blind to the way his work played out in a wider political context. He did not want to believe, almost to the point of utter refusal, that his work gave succor to right-wing racialist groups. But there is little doubt that Jensen and Eysenck helped revive the confidence of these groups. [...] It was unexpected vindication from a respectable scientific quarter. The cautionary language of Eysenck's interpretation of the evidence made little difference. To the racialist right, a genetic basis for group differences in intelligence bore out racialist claims of inherent, immutable hierarchy.[64]

According to Buchanan, Eysenck believed that the quality of his research would "help temper social wrongs and excesses".[64]Eysenck's defence was that he did not shy away from publishing or being interviewed in controversial publications, and that he did not necessarily share their editorial viewpoint. As examples, Buchanan mentions contributions by Eysenck to pornographic magazinesMayfairandPenthouse.[64]

Eysenck described his views in the introduction toRace, Education and Intelligence:

My recognition of the importance of the racial problem, and my own attitudes of opposition to any kind of racial segregation, and hatred for those who suppress any sector of the community on grounds of race (or sex or religion) were determined in part by the fact that I grew up in Germany, at a time when Hitlerism was becoming the very widely held doctrine which finally prevailed and led to the deaths of several million Jews whose only crime was that they belonged to an imaginary "race" which had been dreamed up by a group of men in whom insanity was mixed in equal parts with craftiness, paranoia with guile, and villainy with sadism.[67]

Parapsychology and astrology

editEysenck believed that empirical evidence supportedparapsychologyandastrology.[68][69]He was criticised byscientific skepticsfor endorsingfringe science.Henry Gordonfor example stated that Eysenck's viewpoint was "incredibly naive" because many of the parapsychology experiments he cited as evidence contained serious problems and were never replicated.[70]Magician and skepticJames Randinoted that Eysenck had supported fraudulent psychics as genuine and had not mentioned theirsleight of hand.According to Randi, he had given "a totally-one sided view of the subject".[71]In 1983, Eysenck andCarl Sargentpublished their bookKnow Your Own Psi-IQ,which was designed to test readers'extrasensory perceptionabilities.[72]According to Randi, "the authors instead gave users a highly biased procedure that would make experiments meaningless and certainly discourage further investigation by the amateur."[72]

Later work

editIn 1994, he was one of 52 signatories on "Mainstream Science on Intelligence",[73]an editorial written byLinda Gottfredsonand published inThe Wall Street Journal,which described the consensus of the signing scholars on issues related to intelligence research following the publication of the bookThe Bell Curve.[74]Eysenck included the entire editorial in his 1998 bookIntelligence: A New Look.[75]

Posthumous reevaluation

editEysenck's work has undergone reevaluation since his death.

PsychologistDonald R. Petersonnoted in letters written in 1995 and published in 2005 that years earlier he had stopped trusting Eysenck's work after he tried to replicate a study done in Eysenck's lab and concluded that the results of the original study must have been "either concocted or cooked".[76]

2019 King's College London enquiry

editIn 2019 the psychiatristAnthony Pelosi,writing for theJournal of Health Psychology,described Eysenck's work as unsafe.[77][78]Pelosi described some of Eysenck's work as leading to "one of the worstscientific scandalsof all time ",[7]with "what must be the most astonishing series of findings ever published in thepeer-reviewedscientific literature "[7]and "effect sizesthat have never otherwise been encountered in biomedical research. "[7]Pelosi cited 23 "serious criticisms" of Eysenck's work that had been published independently by multiple authors between 1991 and 1997, noting that these had never been investigated "by any appropriate authority" at that time.[77]The reportedly fraudulent papers covered the links between personality andcancer.Grossarth and Eysenck claimed the existence of a "cancer prone personality" were supposed to have a risk of dying of cancer 121 times greater than controls, when exposed to thecarcinogenphysical factor tobacco smoking. Bosely (2019): The "heart disease-prone personality" exposed to physical risk factors is asserted to have 27 times the risk of dying of heart disease as controls.[7]Pelosi concluded "I honestly believe, having read it so carefully and tried to find alternative interpretations, that this is fraudulent work."[7]

Pelosi's writing prompted additional analysis from other academics and journalists. Citing Pelosi, psychologistDavid F. Markswrote an open letter (also published in theJournal of Health Psychology) calling for the retraction or correction of 61 additional papers by Eysenck.[79][80]In 2019, 26 of Eysenck's papers (all coauthored withRonald Grossarth-Maticek) were "considered unsafe" by an enquiry on behalf ofKing's College London.[6][7][78]It concluded that these publications describing experimental or observational studies were unsafe. It decided that the editors of the 11 journals in which these studies appeared should be informed of their decision.[6][7]All of the 26 papers were cited in Marks' open letter.[79]

The publications under discussion were criticized, among other things, for the reason that Eysenck's research work was partly financed by the tobacco industry and he therefore may have had an interest to show an association between personality and cancer (instead of an association of smoking and cancer).[citation needed]Eysenck said in 1990, "Note that I have never stated that cigarette smoking is not causally related to cancer and coronary heart disease; to deny such a relationship would be irresponsible and counter to the evidence. I have merely stated that the available evidence is insufficient toprovea causal relationship, and this I believe to be true. "In his statement at the time, Eysenck failed to take into account the highly addictive effect ofnicotine,which was only later clearly proven byneurophysiologicalstudies.[82][non-primary source needed]

Grossarth emphasized that the development of disease is often multicausal, whereby the factors reinforce each other in their effect, and he explicitly speaks ofbehavioralcharacteristics that maychangedue topsychological intervention.Grossarth emphasises their changeability throughcognitive behavioral therapyin his intervention studies. Noting that Eysenck died many years ago and cannot defend himself, Grossarth-Maticek wrote a rebuttal and announced legal actions.[81]

Following the King's College London enquiry theInternational Journal of Sport Psychologyretracted a paper that was coauthored by Eysenck in 1990.[83]Later, 13 additional papers were retracted.[84]As of the end of 2020, there had been fourteen retractions and seventy-one expressions of concern on papers from as far back as 1946.[85]Some of these are early papers having nothing to do with health and the King's College enquiry "did not specifically name the articles this expression of concern relates to as problematic".[86]

Portraits

editThere are five portraits of Eysenck in the permanent collection of theNational Portrait Gallery, London,including photographs byAnne-Katrin PurkissandElliott and Fry.[87]

Biographies

edit- Buchanan, Roderick D. (2010).Playing with Fire: The Controversial Career of Hans J. Eysenck.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-856688-5.,review in:Rose, Steven (August 2010). "Hans Eysenck's controversial career".The Lancet.376(9739): 407–408.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61207-X.S2CID54303305.

- Corr, P. J. (2016).Hans Eysenck: A Contradictory Psychology.Macmillan Education-Palgrave.ISBN978-0-230-24940-0.

- Eysenck, Hans (1997).Rebel with a cause.Transaction Publishers.ISBN978-1-56000-938-2.

- Gibson, H. B.(1981).Hans Eysenck: The man and his work.Peter Owen.ISBN978-0-7206-0566-2.

Works

editBooks

edit- Dimensions of Personality(1947)

- The Scientific Study of Personality(1952)

- The Structure of Human Personality(1952) and later editions

- Uses and Abuses of Psychology(1953)

- The Psychology of Politics(1954)

- Psychology and the Foundations of Psychiatry(1955)

- Sense and Nonsense in Psychology(1956)

- The Dynamics of Anxiety and Hysteria(1957)

- Perceptual Processes and Mental Illnesses(1957) with G. Granger and J. C. Brengelmann

- Manual of the Maudsley Personality Inventory(1959)

- Know Your Own I.Q.(1962)

- Crime and Personality(1964) and later editions

- Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory(1964) with S. B. G. Eysenck

- The Causes and Cures of Neuroses(1965) with S. Rachman

- Fact and Fiction in Psychology(1965)

- Smoking, Health and Personality(1965)

- Check Your Own I.Q.(1966)

- The Effects of Psychotherapy(1966)

- The Biological Basis of Personality(1967)

- Eysenck, H. J. & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1969).Personality Structure and Measurement.London: Routledge.

- Readings in Extraversion/Introversion(1971) three volumes

- Race, Intelligence and Education(1971) in US asThe IQ Argument

- Psychology is about People(1972)

- Lexicon de Psychologie(1972) three volumes, with W. Arnold and R. Meili

- The Inequality of Man(1973). German translationDie Ungleichheit der Menschen.Munich: Goldman. 1978. With an introduction by Eysenck.

- Eysenck, Hans J.; Wilson, Glenn D. (1973).The Experimental Study of Freudian Theories.London: Methuen.

- Eysenck, Hans J.; Wilson, Glenn D. (1976).Know your own personality.Harmondsworth, Eng. Baltimore etc: Penguin Books.ISBN978-0-14-021962-3.

- Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire(1975) with S. B. G. Eysenck

- Eysenck, Hans J.; Wilson, Glenn D. (1976).A Textbook of Human Psychology.Lancaster: MTP Press.

- Sex and Personality(1976)

- Eysenck, H. J. & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1976).Psychoticism as a Dimension of Personality.London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Reminiscence, Motivation and Personality(1977) with C. D. Frith

- You and Neurosis(1977)

- Die Zukunft der Psychologie(1977)

- Eysenck, Hans J.; Nias, David K. B. (1979).Sex, violence, and the media.New York: Harper Collins.ISBN978-0-06-090684-9.

- The Structure and Measurement of Intelligence(1979)

- Eysenck, Hans J.; Wilson, Glenn D. (1979).The psychology of sex.London: J. M. Dent.ISBN978-0-460-04332-8.

- The Causes and Effects of Smoking(1980)

- Mindwatching(1981) with M. W. Eysenck, and later editions

- The Battle for the Mind(1981) withL. J. Kamin,in US asThe Intelligence Controversy

- Personality, Genetics and Behaviour(1982)

- Explaining the Unexplained(1982, 2nd edition 1993) withCarl Sargent

- H. J. Eysenck & D. K. B. Nias,Astrology: Science or Superstition?Penguin Books (1982),ISBN0-14-022397-5

- Know Your Own Psi-Q(1983) withCarl Sargent

- …'I Do'. Your Happy Guide to Marriage(1983) with B. N. Kelly.

- Personality and Individual Differences: A Natural Science Approach(1985) with M. W. Eysenck

- Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire(1985)

- Rauchen und Gesundheit(1987)

- The Causes and Cures of Criminality(1989) with G. H. Gudjonsson

- Genes, Culture and Personality: An Empirical Approach(1989) with L. Eaves and N. Martin

- Mindwatching(1989) with M. W. Eysenck. Prion,ISBN1-85375-194-4

- Genius: The natural history of creativity(1995). Cambridge University Press,ISBN0-521-48014-0

- Intelligence: A New Look(1998)

Edited books

edit- Handbook of Abnormal Psychology(1960), later editions

- Experiments in Personality(1960) two volumes

- Behaviour Therapy and Neuroses(1960)

- Experiments with Drugs(1963)

- Experiments in Motivation(1964)

- Eysenck on Extraversion(1973)

- The Measurement of Intelligence(1973)

- Case Histories in Behaviour Therapy(1974)

- The Measurement of Personality(1976)

- Eysenck, Hans J.; Wilson, Glenn D. (1978).The Psychological basis of ideology.Baltimore: University Park Press.ISBN978-0-8391-1221-1.

- A Model for Personality(1981)

- A Model for Intelligence(1982)

- Suggestion and Suggestibility(1989) with V. A. Gheorghiu, P. Netter, and R. Rosenthal

- Personality Dimensions and Arousal(1987) with J. Strelau

- Theoretical Foundations of Behaviour Therapy(1988) with I. Martin

Other

edit- Preface to Pierre Krebs.Das Unverganglich Erbe

See also

editReferences

edit- ^"Hans Eysenck Official Site".Hans Eysenck.Retrieved30 January2020.

- ^Boyle, G.J., & Ortet, G. (1997). Hans Jürgen Eysenck: Obituario.Ansiedad y Estrés (Anxiety and Stress), 3,i-ii.

- ^Boyle, G.J. (2000). Obituaries: Raymond B. Cattell and Hans J. Eysenck.Multivariate Experimental Clinical Research, 12,i-vi.

- ^Haggbloom, S. J. (2002). "The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century".Review of General Psychology.6(2): 139–152.doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139.S2CID145668721.

- ^abcdO'Grady, Cathleen (15 July 2020)."Misconduct allegations push psychology hero off his pedestal".Science | AAAS.Retrieved24 July2020.

- ^abcd"King's College London enquiry into publications authored by Professor Hans Eysenck with Professor Ronald Grossarth-Maticek"(PDF).October 2019.

- ^abcdefghiBoseley, Sarah (11 October 2019)."Work of renowned UK psychologist Hans Eysenck ruled 'unsafe'".The Guardian.

- ^Marks, David F; Buchanan, Roderick D (January 2020)."King's College London's enquiry into Hans J Eysenck's 'Unsafe' publications must be properly completed".Journal of Health Psychology.25(1): 3–6.doi:10.1177/1359105319887791.PMID31841048.

- ^abRose, Steven (7 August 2010)."Hans Eysenck's controversial career".The Lancet.376(9739): 407–408.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61207-X.ISSN0140-6736.S2CID54303305.Retrieved24 March2022.

- ^abColman, Andrew M.(December 2016)."Race differences in IQ: Hans Eysenck's contribution to the debate in the light of subsequent research".Personality and Individual Differences.103:182–189.doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.050.hdl:2381/37768.

To many people, Hans Eysenck's name is principally associated with certain claims that he first published in 1971 about the heritability of intelligence and race differences in IQ scores.

- ^abcdEysenck, H. J.,Rebel with a Cause (an Autobiography),London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1990

- ^Buchanan, R. D. (2010).Playing With Fire: The Controversial Career of Hans J. Eysenck.Oxford University Press. pp. 25–30.ISBN978-0-19-856688-5.

- ^"Hans Jürgen Eysenck Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia articles about Hans Jürgen Eysenck".Encyclopedia.Retrieved22 July2011.

- ^Behaviour Therapy and the Neurosis,edited by Hans Eysenck, London: Pergamon Press, 1960.

- ^Eysenck, Hans J.,Experiments in Behaviour Therapy,London:Pergamon Press,1964.

- ^"Buchanan, R. D." Looking back: The controversial Hans Eysenck ",The Psychologist, 24,Part 4, April 2011 ".Archived fromthe originalon 26 August 2014.Retrieved18 April2012.

- ^"About Us".World Cultural Council.Retrieved8 November2016.

- ^Honan, William H.(10 September 1997)."Hans J. Eysenck, 81, a Heretic in the Field of Psychotherapy".The New York Times.Retrieved4 May2010.

- ^"APA Presidents Remember: Hans Eysenck — Visionary Psychologist".Archived fromthe originalon 7 October 2008.Retrieved13 November2008.

- ^"Hans J. Eysenck".Archived fromthe originalon 6 November 2008.Retrieved13 November2008.

- ^Martin, Michael (2007).The Cambridge Companion to Atheism.Cambridge University Press. p. 310.ISBN9780521842709.

Among celebrity atheists with much biographical data, we find leading psychologists and psychoanalysts. We could provide a long list, including...Hans Jürgen Eysenck...

- ^Marsh, Laurence (Winter 2021)."When is a house unique?".Herne Hill(152). Herne Hill Society.

- ^"Classics in the History of Psychology – Eysenck (1957)".Psychclassics.yorku.ca. 23 January 1952.Retrieved22 July2011.

- ^"Humanist Manifesto II".American Humanist Association. Archived fromthe originalon 20 October 2012.Retrieved3 October2012.

- ^Altemeyer, Bob.Right Wing Authoritarianism(Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press, 1981) 80–91,ISBN0-88755-124-6.

- ^Eysenck, H. (1971).Race, Intelligence and Education.London: Maurice Temple Smith.

- ^Boyle, Gregory J.; Stankov, Lazar; Martin, Nicholas G.; Petrides, K.V.; Eysenck, Michael W.; Ortet, Generos (December 2016)."Hans J. Eysenck and Raymond B. Cattell on intelligence and personality"(PDF).Personality and Individual Differences.103:40–47.doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.029.S2CID151437650.

- ^Roger Pearson,Race, Intelligence and Bias in Academe,2nd edition, Scott-Townsend (1997),ISBN1-878465-23-6,pp. 34–38.

- ^Staff Reporter (12 September 1997)."Scientist or showman?".Mail & Guardian.Africa.Retrieved23 June2022.

- ^Eysenck, Hans J.,Rebel with a Cause (an Autobiography),London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1990, pp. 289–291.

- ^BBC televisionseriesFace To Face• Hans Eysenck – broadcast 16 October 1990.

- ^abBarnett, S. A. (1988).Biology and Freedom: An Essay on the Implications of Human Ethology.Cambridge University Press. pp. 160–161.ISBN978-0-521-35316-8.

- ^Sandra Scarr (1976)."Unknowns in the IQ equation".In Ned Joel Block and Gerald Dworkin (ed.).The I.Q. Controversy: Critical Readings.Pantheon Books. p.114.ISBN978-0-394-73087-5.

- ^Sandra Scarr (1976)."Unknowns in the IQ equation".In Ned Joel Block and Gerald Dworkin (ed.).The I.Q. Controversy: Critical Readings.Pantheon Books. p.116.ISBN978-0-394-73087-5.

- ^abcScarr, Sandra (1981).Race, Social Class, and Individual Differences in IQ.Psychology Press. pp. 62–65.ISBN978-0-89859-055-5.

- ^William H. Tucker,The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund.University of Illinois Press, 2002.

- ^"Grantees".Pioneerfund.org. Archived fromthe originalon 27 July 2011.Retrieved22 July2011.

- ^Archived atGhostarchiveand theWayback Machine:Hans Eysenck (1994) personality and cancer lecture,13 September 2015,retrieved30 January2020

- ^Example document here"Memorandum Regarding Professor Eysenck's Research Progress".Archived12 January 2012 at theWayback Machine

- ^Peter pringle, "Eysenck took pounds 800,000 tobacco funds",The Independent,31 October 1996.

- ^Eysenck, H. J.; Tarrant, Mollie; Woolf, Myra; England, L. (14 May 1960)."Smoking and Personality".British Medical Journal.1(5184): 1456–1460.doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5184.1456.PMC1967328.PMID13821141.

- ^Eysenck, H.J. (July 1964). "Personality and cigarette smoking".Life Sciences.3(7): 777–792.doi:10.1016/0024-3205(64)90033-5.PMID14203979.

- ^Eysenck, H.J. (1988). "The respective importance of personality, cigarette smoking and interaction effects for the genesis of cancer and coronary heart disease".Personality and Individual Differences.9(2): 453–464.doi:10.1016/0191-8869(88)90123-7.

- ^Buchanan, Roderick D. (2010).Playing with Fire: The Controversial Career of Hans J. Eysenck.OUP Oxford. p. 376.ISBN978-0-19-856688-5.

- ^Eysenck, H.J. (January 1994). "Cancer, personality and stress: Prediction and prevention".Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy.16(3): 167–215.doi:10.1016/0146-6402(94)00001-8.

- ^The Journal of Mental Health,July 1951, Vol. XCVII, "The Inheritance of Neuroticism: An Experimental Study", H. J. Eysenck and D. B. Prell, p. 402.

- ^H. J. Eysenck and S. B. G. Eysenck (1976).Psychoticism as a Dimension of Personality.London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- ^Eysenck, H. J. (1967).The Biological Basis of Personality.Springfield, IL: Thomas.

- ^(Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985)

- ^Thomas, Kerry. (2007). The individual differences approach to personality. InMapping Psychology(p. 315). The Open University.

- ^Boyle, G. J. (2008). Critique of Five-Factor Model (FFM). In G. J. Boyle et al. (Eds.),The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Vol. 1 - Personality Theories and Models.Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publishers.ISBN978-1-4129-4651-3ISBN1-4129-2365-4

- ^Grohol, John M. (30 May 2019)."The Big Five Personality Traits".psychcentral.Retrieved22 August2020.

- ^Eysenck, H.J. (June 1992). "Four ways five factors are not basic".Personality and Individual Differences.13(6): 667–673.doi:10.1016/0191-8869(92)90237-J.

- ^abFurnham, A., Eysenck, S. B. G., & Saklofske, D. H. (2008). The Eysenck personality measures: Fifty years of scale development. In G.J. Boyle, G. Matthews, & D.H. Saklofske. (Eds.),The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Vol. 2 – Personality Measurement and Testing(pp. 199-218). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publishers.

- ^Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975).Manual of the Eysenck Personality Qyestionnaire (Junior and Adult).London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- ^Eysenck, H. J., & Wilson, G. D. (1991).The Eysenck Personality Profiler.London: Corporate Assessment Network.

- ^Christina Schori-Liang.Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right.Ashgate 2007. p.160.

- ^Siegfried Jäger. "Der Singer-Diskurs sowie einige Bemerkungen zu seiner Funktion für die Stärkung rassistischer und rechtsextremer Diskurse in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland".First appeared in Siegfried Jäger andJobst Paul(1991).Von Menschen und Schweinen. Der Singer-Diskurs und seine Funktion für den Neo-Rassismus.Duisburg: Diss-Texte Nr. 13. p. 7-30.ISBN3885151219.Quotation: "Eysenck stellt sich zudem rückhaltlos hinter rechtsextreme Theorie-Zirkel wie z.B. das Kasseler Thule-Seminar. Zu dem von dessen Leiter herausgegebenen Buch mit dem Titel" Das unvergängliche Erbe "verfaßte er das Vorwort, in dem er gegen die Gleichheit der Menschen wettert, indem er sie als" unhaltbare ideologische Doktrin "abtut. (in Krebs 1981, S. 12)"

- ^Roderick D. Buchanan (2010).Playing With Fire: The Controversial Career of Hans J. Eysenck.Oxford University Press. pp. 324–326.ISBN978-0-19-856688-5.

- ^Roderick D. Buchanan (2010).Playing With Fire: The Controversial Career of Hans J. Eysenck.Oxford University Press. pp. 320–321.ISBN978-0-19-856688-5.

- ^Roderick D. Buchanan (2010).Playing With Fire: The Controversial Career of Hans J. Eysenck.Oxford University Press. p. 323.ISBN978-0-19-856688-5.

- ^Stefan Kuhl (1994).The Nazi Connection:Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism.Oxford University Press. p. 5.ISBN978-0-19-988210-6.

- ^J.G. Shields (2007).The Extreme Right in France.Taylor & Francis. pp. 150, 145.ISBN978-0-415-09755-0.

- ^abcdeRoderick D. Buchanan (2010).Playing With Fire: The Controversial Career of Hans J. Eysenck.Oxford University Press. p. 323.ISBN978-0-19-856688-5.

- ^Leonie Knebel and Pit Marquardt (2012)."Vom Versuch, die Ungleichwertigkeit von Menschen zu beweisen".In Michael Haller and Martin Niggeschmidt (ed.).Der Mythos vom Niedergang der Intelligenz: Von Galton zu Sarrazin: Die Denkmuster und Denkfehler der Eugenik.Springer DE. p. 104.doi:10.1007/978-3-531-94341-1_6.ISBN978-3-531-18447-0.referring toP. Krebs,ed. (1981).Das unvergängliche Erbe. Alternativen zum Prinzip der Gleichheit.Tübingen:Grabert Verlag.ISBN978-3-87847-051-9.

- ^Michael Billig, (1979)Psychology, Racism, and FascismArchived3 March 2016 at theWayback Machine,on-line edition

- ^Hans Eysenck (1973).Race, Education and Intelligence.Maurice Temple Smith. pp. 9–10.ISBN978-0-8511-7009-1.

- ^Eysenck, H. J. (1957),Sense and Nonsense in Psychology.London: Pelican Books. p. 131.

- ^Eysenck &Sargent(2nd edition, 1993),Explaining the Unexplained.London: BCA, No ISBN. Preface & ff.

- ^Gordon, Henry. (1988).Extrasensory Deception: ESP, Psychics, Shirley MacLaine, Ghosts, UFO.Prometheus Books. pp. 139-140.ISBN0-87975-407-9

- ^Nias, David K. B.; Dean, Geoffrey A. (2012)."Astrology and Parapsychology".In Modgil, Sohan; Modgil, Celia (eds.).Hans Eysenck: Consensus And Controversy.pp. 371–388.doi:10.4324/9780203299449-38.ISBN978-0-203-29944-9.

- ^abRandi, James(1995).An encyclopedia of claims, frauds, and hoaxes of the occult and supernatural: decidedly sceptical definitions of alternative realities.New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin.ISBN978-0-312-15119-5.

- ^Gottfredson, Linda (13 December 1994).Mainstream Science on Intelligence.Wall Street Journal,p. A18.

- ^Gottfredson, Linda (1997). "Mainstream Science on Intelligence: An Editorial With 52 Signatories, History, and Bibliography".Intelligence.24(1): 13–23.doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(97)90011-8.

- ^Eysenck, Hans (1998).Intelligence: A New Look.New Brunswick (NJ): Transaction Publishers. pp. 1–6.ISBN978-1-56000-360-1.

- ^Peterson, Donald R.(2005).Twelve Years of Correspondence with Paul Meehl: Tough Notes from a Gentle Genius.Mahwah, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.pp. 23, 136.doi:10.4324/9781315084510.ISBN9780805854893.OCLC57754047.

- ^abcPelosi, Anthony J. (2019)."Personality and fatal diseases: Revisiting a scientific scandal".Journal of Health Psychology.24(4): 421–439.doi:10.1177/1359105318822045.PMC6712909.PMID30791726.

- ^abBoseley, Sarah (11 October 2019)."Work of renowned UK psychologist Hans Eysenck ruled 'unsafe'".The Guardian– via theguardian.

- ^abMarks, David F(March 2019)."The Hans Eysenck affair: Time to correct the scientific record".Journal of Health Psychology.24(4): 409–420.doi:10.1177/1359105318820931.PMID30791728.

- ^"Is this 'one of the worst scientific scandals of all time'?".Cosmos Magazine.21 October 2019.Retrieved3 November2019.

- ^abGrossarth-Maticek, Ronald."Answers to Pelosi and Marks".Krebs Chancen.Retrieved19 November2019.

- ^Aho v. Suomen; Tupakka Oy:Tobacco Documents Library Id: kqgf0028. Available at: Truth Tobacco Industry documents: Sworn statement of HANS JURGEN EYSENCK, Ph.D., Sc.D.,December 10, 1990, page 10 – 11 and following.

- ^Oransky, Ivan (21 January 2020)."Journal retracts 30-year-old paper by controversial psychologist Hans Eysenck".Retraction Watch.Retrieved22 January2020.

- ^Oransky, Ivan (12 February 2020)."Journals retract 13 papers by Hans Eysenck, flag 61, some 60 years old".Retraction Watch.Retrieved13 February2020.

- ^Marks, David F. (November–December 2020)."Hans J. Eysenck: The Downfall of a Charlatan".Skeptical Inquirer.Amherst, New York:Center for Inquiry.pp. 35–39.Retrieved16 February2021.

- ^"EXPRESSION OF CONCERN: Articles by Hans J. Eysenck".Perceptual and Motor Skills.124(2): 922–924.

- ^"National Portrait Gallery – Person – Hans Jürgen Eysenck".Npg.org.uk. 1 October 1950.Retrieved22 July2011.

Further reading

edit- Goldberg, Lewis R.; Rosolack, Tina K. (2014)."The Big Five factor structure as an integrative framework: An empirical comparison with Eysenck's P-E-N model".In Halverson, Charles F.; Kohnstamm, Gedolph A.; Martin, Roy P. (eds.).The Developing Structure of Temperament and Personality From Infancy To Adulthood.Psychology Press. pp. 7–35.ISBN978-1-317-78179-0.

External links

edit- Hans Eysenck:Hour-long lecture on the "Biological Basis of Personality"onYouTube(St Göran lecture, 1980).