TheLapis Niger(Latin,"Black Stone" ) is an ancient shrine in theRoman Forum.Together with the associatedVulcanal(a sanctuary toVulcan) it constitutes the only surviving remnants of the oldComitium,an early assembly area that preceded the Forum and is thought to derive from an archaic cult site of the 7th or 8th century BC.

| |

| Location | Regione VIIIForum Romanum |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′33″N12°29′5″E/ 41.89250°N 12.48472°E |

| Type | Shrine |

| History | |

| Builder | Tullus Hostilius |

| Founded | 5th century BC |

The black marble paving (1st century BC) and modern concrete enclosure (early 20th century) of the Lapis Niger overlie an ancient altar and a stone block with one of the earliest knownOld Latininscriptions (c. 570–550 BC). The superstructure monument and shrine may have been built byJulius Caesarduring his reorganization of the Forum and Comitium space. Alternatively, this may have been done a generation earlier bySulladuring one of his construction projects around theCuria Hostilia.The site was rediscovered and excavated from 1899 to 1905 by ItalianarchaeologistGiacomo Boni.

Mentioned in many ancient descriptions of the Forum dating back to theRoman Republicand the early days of theRoman Empire,the significance of the Lapis Niger shrine was obscure and mysterious to later Romans, but it was always discussed as a place of great sacredness and significance. It is constructed on top of a sacred spot consisting of much older artifacts found about 5 ft (1.5 m) below the present ground level. The name "black stone" may have originally referred to the black stone block (one of the earliest known Latin inscriptions) or it may refer to the later black marble paving at the surface. Located in the Comitium in front of theCuria Julia,this structure survived for centuries due to a combination of reverential treatment and overbuilding during the era of the early Roman Empire.

History

editThe site is believed to date back to theRoman regal period.The inscription includes the wordrex,probably referring to either a king (rex), or to therex sacrorum,a high religious official. At some point, the Romans forgot the original significance of the shrine. This led to several conflicting stories of its origin. Romans believed the Lapis Niger marked either the grave of the first king of Rome,Romulus,or the spot where he was murdered by the Senate;[1]the grave ofHostus Hostilius,grandfather of KingTullus Hostilius;or the location whereFaustulus,foster father of Romulus, fell in battle.

The earliest writings referring to this spot regard it as asuggestumwhere the early kings of Rome would speak to the crowds at the forum and to the Senate. The two altars are common at shrines throughout the early Roman or late Etruscan period.

The Lapis Niger is mentioned in an uncertain and ambiguous way by several writers of the early Imperial period:Dionysius of Halicarnassus,Plutarch,andFestus.They do not seem to know which old stories about the shrine should be believed.

In November 2008 heavy rain damaged the concrete covering that has been protecting the Vulcanal and its monuments since the 1950s. This includes the inscribed stone block accorded the name of "The Black Stone" or Lapis Niger (the marble and cement covering is a mix of the original black marble said to have been used to cover the site by Sulla, and modern cement used to create the covering and keep the marble in place). An awning now protects the ancient relics until the covering is repaired, allowing the public to view the originalsuggestumfor the first time in 50 years.[2]The nature of the coverings and ongoing repairs makes it impossible to see the Lapis Niger which is several meters underground.

Description

editThe shrine

editThe Lapis Niger went through several incarnations. The initial versions were destroyed by fire or the sacking of the city and buried under the slabs of black marble. It is believed this was done by Sulla; however, it has also been argued that Julius Caesar may have buried the site during his re-alignment of the Comitium.

The original version of the site, first excavated in 1899, included a truncated cone oftuff(possibly a monument) and the lower portion of a square pillar (cippus) which was inscribed with anOld Latininscription, perhaps the oldest in existence if not theDuenos inscriptionor thePraeneste fibula.A U-shaped altar, of which only the base still survives, was added some time later. In front of the altar are two bases, which may also have been added separately from the main altar. The antiquarianVerrius Flaccus(whose work is preserved only in the epitome of Pompeius Festus), a contemporary ofAugustus,described a statue of a resting lion placed on each base, "just as they may be seen today guarding graves". This is sometimes referred to as the Vulcanal. Also added at another period was an honorary column, possibly with a statue topping it.

Archaeological excavations (1899–1905) revealed various dedicatory items from vase fragments, statues and pieces of animal sacrifices around at the site in a layer of deliberately placed gravel. All these artifacts date from very ancient Rome, between the 5th and 7th centuries BC.

The second version, placed when the first version was demolished in the 1st century BC to make way for further development in the forum, is a far simpler shrine. A pavement of black marble was laid over the original site and was surrounded by a low white wall or parapet. The new shrine lay just beside theRostra,the senatorial speaking platform.

The inscription

editThe inscription on the stone block has various interesting features. The lettering is closer toGreek lettersthan any known Latin lettering, since it is chronologically closer to the original borrowing of the Greek Alpha bet by peoples of Italy fromItalian Greek colonies,such asCumae.The inscription is writtenboustrophedon.Many of the oldest Latin inscriptions are written in this style. The meaning of the inscription is difficult to discern as the beginning and end are missing and only one third to one half of each line survives. It appears, however, to dedicate the shrine to arexor king and to level grave curses at anyone who dares disturb it.

Attempts have been made at interpreting the meaning of the surviving fragment by Johannes Stroux,[3]Georges DumézilandRobert E. A. Palmer.

Here is the reading of the inscription as given by Dumézil (on the right the reading by Arthur E. Gordon[4]):

|

|

(Roman numbers represent the four faces of thecippus(pedestal) plus the edge. Fragments on each face are marked with letters (a, b, c). Arabic numbers denote lines. A sign (/) marks the end of a line).

(The letters whose reading is uncertain or disputed are given in italics. The extension of the lacuna is uncertain: it may vary from1⁄2to2⁄3or even more. In Gordon's reading thevofduoin line 11 is read inscribed inside theo.)

Dumézil declined to interpret the first seven lines on the grounds that the inscription was too damaged, while acknowledging it was a prohibition under threat.

Dumézil's attempt[5]is based on the assumption of a parallelism of some points of the fragmentary text inscribed on the monument and a passage ofCicero'sDe Divinatione(II 36. 77). In that passage, Cicero, discussing the precautions taken byaugursto avoid embarrassingauspices,states: "to this is similar what we augurs prescribe, in order to avoid the occurrence of theiuges auspicium,that they order to free from the yoke the animals (which are yoked) ".[6]'They' here denotes thecalatores,public slaveswhom the augurs and othersacerdotes(priests) had at their service, and who, in the quoted passage, are to execute orders aimed at preventing profane people from spoiling and, by their inadvertent action thereby rendering void, the sacred operation.[7] Even though impossible to connect meaningfully to the rest of the text, the mention of therexin this context would be significant as at the time of the Roman monarchy, augury was considered as pertaining to the king: Cicero in the same treatise states: "Divination, as well as wisdom, was consideredregal".[8]

Theiuges auspiciumare defined thus byPaul the Deacon:[9]"Theiuges auspiciumoccur when an animal under the yoke makes its excrements ".

Varroin explaining the meaning of the name of theVia Sacra,states that the augurs, advancing along this street after leaving thearxused toinaugurate.[10]While advancing along theVia Sacrathey should avoid meeting aiuges auspicium.As theVia Sacrabegins on theCapitoland stretches along the wholeForum,in the descent from the hill to the Forum the first crossing they met, i.e. the first place where the incident in question could happen, was namedVicus Jugarius:Dumézil thinks its name should be understood according to the prescription on issue.[11]In fact theComitium,where thecippuswas found, is very close to the left side of this crossing. This fact would make it natural that thecippuswere placed exactly there, as a warning to passers by of the possible occurrence of the order of thecalatores.

In support of such an interpretation of the inscription, Dumézil emphasises the occurrence of the wordrecei(dative caseofrex). Lines 8-9 could be read as: (the augur or the rex)[... iubet suu]m calatorem ha[ec *calare],lines 10–11 could be[... iug]ō(or[... subiugi]ōor[... iugari]ō) iumenta capiat,i.e.: "that he take the yoked animals from under the yoke" (with a separation prefixexordebefore the ablative as in Odyssea IX 416:"άπο μεν λίθον ειλε θυράων"=capere). Line 12 could be accordingly interpreted as:[... uti augur/ rex ad...-]m iter pe[rficiat].

The remaining lines could also be interpreted similarly, in Dumézil's view:iustumandliquidumare technical terms used as qualifying auspices, meaning regular, correctly taken and favourable.[12]Moreover, the original form of classic Latinaluus,'abdomen', and also stools, as still attested inCato Maiorwas *aulos,thatMax Niedermannon the grounds ofLithuanianreconstructs as *au(e)los.Thehinquoihauelodcould denote a hiatus as inahēn(e)us,huhuic(i.e. bisyllablehuic). Dumézil then proposes the following interpretation for lines 12–16:... ne, descensa tunc iunctorum iumentoru]m cui aluo, nequ[eatur(religious operation under course in the passive infinitive)auspici]o iusto liquido.The hiatus marked byhin line 13 would require to read the antecedent word asquoii,dative ofquoi:quoieiis the ancient dative of the accentuated relative pronoun, but one could suppose that in the enclitic indefinite pronoun the dative could have early been reduced toquoiī.Theeinauelodcan be an irrational vowel as innumerusfrom *nom-zo:cf. EtruscanAvile.As forloi(u)quod,it may be an archaic form of a type of which one can cite other instances, aslucidusandLucius,fluuidusandflŭuius,liuidusandLīuius.

Michael Grant,in his bookRoman Forumwrites: "The inscription found beneath the black marble... clearly represents a piece of ritual law... the opening words are translatable as a warning that a man who damages, defiles or violates the spot will be cursed. One reconstruction of the text interprets it as referring to the misfortune which could be caused if two yoked draught cattle should happen while passing by to drop excrement simultaneously. The coincidence would be a perilous omen".[13]

That the inscription may contain some laws of a very early period is also acknowledged by Allen C. Johnson.[14]

Palmer instead, on the basis of a detailed analysis of every recognisable word, gave the following interpretation of this inscription, which he too considers to be a law:

Whosoever (will violate) this (grove), let him be cursed. (Let no one dump) refuse (nor throw a body...). Let it be lawful for the king (to sacrifice a cow in atonement). (Let him fine) one (fine) for each (offence). Whom the king (will fine, let him give cows). (Let the king have a —) herald. (Let him yoke) a team, two heads, sterile… Along the route... (Him) who (will) not (sacrifice) with a young animal.. in... lawful assembly in grove...[15]

See also

editFurther reading

edit- Johannes Stroux:Die Foruminschrift beim Lapis nigerIn: Philologus, Vol. 86 (1931), p. 460.

References

edit- ^Festus,De verborum significatus.v. lapis niger.

- ^Owen, Richard."Site of Romulus's murder to be tourist draw".London: Times Online.Retrieved2008-07-01.

- ^Johannes Stroux."Die Foruminschrift beim Lapis niger".InPhilologusVol. 86 (1931), p. 460.

- ^Arthur E. Gordon (1983).Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy.Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 79.

- ^

- "Lejuges auspiciumet les incongruités du teureau attalé de Mugdala ".InNouvelle Clio51953 p. 249–66.

- "Sur l'inscription du Lapis niger".InRevue d'études latins361958 pp. 109–111 and371959 p. 102.

- ^"Huic simile est, quod nos augures praecipimus, ne iuges auspicium obveniat, ut iumenta iubeant diiungere".

- ^Suetonius,Grammatica12; Servius,Ad GeorgicasI 268; Macrobius,SaturnaliaI 16, 9.

- ^Cicero above I 89.

- ^Paulus ex Festus s.v.iuges auspiciump. 226 L2nd:"iuges auspicium est cum iunctum iumentum stercus fecit".

- ^Varro,De Lingua latinaV 47:"ex arce profecti solent inaugurare".

- ^Dumézil thinks the interpretation of this name that connects it to a cult ofJuno Jugashould be due to an etymological pun.

- ^Dumézil states such a use is attested three times in Plautus.

- ^Michael GrantRoman ForumLondon 1974 p. 50.

- ^Allen Chester Johnson, Paul Robinson Coleman-Norton, Frank Card BourneAncient Roman StatutesUniversity of Texas Press1961 p. 5.

- ^Robert E. A. Palmer (1959).The King and the Comitium. A Study of Rome's Oldest Public Document.Wiesbaden. p.51 ff.Historia. Einzelschriften111969. This interpretation is rejected by G. Dumézil (1970),"À propos de l'inscription du Lapis Niger",Latomus291970 pp. 1039–1045, who finds it impossible understandingkapiafor(iumentorum) capita,from a hypothetical *kape=caput'head', and *louqus-forlūcus'grove'.

External links

edit- Forum Romanum: Rostra, Curia, Decennalia Base and Lapis Niger

- LacusCurtius — Lapis Niger and Sepulchrum Romuli (Christian Hülsen, 1906)

- Lapis niger (Bibliotheca Augustana)

- Digital Roman Forum: Lapis Niger,a 3D computer recreation of the second incarnation of the Lapis Niger

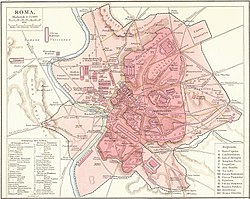

- Plan showing location in the Forum Romanum

- Lapis Niger and Vulcanal