Man'yōgana(Vạn diệp 仮 danh,Japanese pronunciation:[maɰ̃joꜜːɡana]or[maɰ̃joːɡana])is an ancientwriting systemthat usesChinese charactersto represent theJapanese language.It was the first knownkanasystem to be developed as a means to represent the Japanese language phonetically. The date of the earliest usage of this type of kana is not clear, but it was in use since at least the mid-7th century. The name "man'yōgana" derives from theMan'yōshū,aJapanese poetryanthology from theNara periodwritten withman'yōgana.

| Man'yōgana Vạn diệp 仮 danh | |

|---|---|

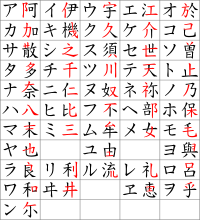

Katakanacharacters and the man'yōgana they originated from | |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 650 CE toMeiji era |

| Direction | Top-to-bottom |

| Languages | JapaneseandOkinawan |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Oracle bone script

|

Child systems | Hiragana,Katakana |

Sister systems | Contemporarykanji |

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(November 2022) |

Texts using the system also often use Chinese charactersfor their meaning,butman'yōganarefers to such characters only when they are used to represent a phonetic value. The values were derived from the contemporary Chinese pronunciation, but native Japanese readings of the character were also sometimes used. For example,Mộc(whose character means 'tree') could represent/mo/(based onMiddle Chinese[məwk]),/ko/,or/kwi/(meaning 'tree' inOld Japanese).[1]

Simplified versions ofman'yōganaeventually gave rise to both thehiraganaandkatakanascripts, which are used in Modern Japanese.[2]

Origin

editScholars from the Korean kingdom ofBaekjeare believed to have introduced theman'yōganawriting system to theJapanese archipelago.The chroniclesKojikiand theNihon shokiboth state so; though direct evidence is hard to come by, scholars tend to accept the idea.[3]

A possible oldest example ofman'yōganais the ironInariyama Sword,which was excavated at the InariyamaKofunin 1968. In 1978,X-rayanalysis revealed a gold-inlaid inscription consisting of at least 115 Chinese characters, and this text, written in Chinese, included Japanese personal names, which were written for names in a phonetic language. This sword is thought to have been made in the yearTân hợi năm(471 AD in the commonly-accepted theory).[4]

There is a strong possibility that the inscription of the Inariyama Sword may be written in a version of the Chinese language used in Baekje.[5]

Principles

editMan'yōganauseskanjicharacters for their phonetic rather than semantic qualities. In other words, kanji are used for their sounds, not their meanings. There was no standard system for choice of kanji, and different ones could be used to represent the same sound, with the choice made on the whims of the writer. By the end of the 8th century, 970 kanji were in use to represent the 90moraeof Japanese.[6]For example, theMan'yōshūpoem 17/4025 was written as follows:

| Man'yōgana | Chi chăng lộ nhưng lương | Nhiều thái cổ muốn lâu lễ bà | Sóng lâu so có thể hải | An tá nại nghệ tư nhiều lý | Thuyền vĩ mẫu ta mao |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katakana | シオジカラ | タダコエクレバ | ハクヒノウミ | アサナギシタリ | フネカジモガモ |

| Modern | Chí hùng lộ から | ただ càng え tới れば | Vũ sao の hải | Triều phong したり | Thuyền vĩ もがも |

| Romanized | Shioji kara | tadakoe kureba | Hakuhi no umi | asanagi shitari | funekaji mogamo |

In the poem, the soundsmo(Mẫu, mao) andshi(Chi, tư) are written with multiple, different characters. All particles and most words are represented phonetically (Nhiều quátada,An táasa), but the wordsji(Lộ),umi(Hải) andfunekaji(Thuyền vĩ) are rendered semantically.

In some cases, specific syllables in particular words are consistently represented by specific characters. That usage is known asJōdai Tokushu Kanazukaiand usage has led historical linguists to conclude that certain disparate sounds inOld Japanese,consistently represented by differing sets ofman'yōganacharacters, may have merged since then.

Types

editIn writing which utilizesman'yōgana,kanji are mapped to sounds in a number of different ways, some of which are straightforward and others which are less so.

Shakuon kana(Mượn âm 仮 danh) are based on a Sino-Japaneseon'yomireading, in which one character represents either onemoraor two morae.[7]

| Morae | 1 character, complete | 1 character, partial |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lấy (い)Lữ (ろ)Sóng (は) | An (あ)Nhạc (ら)Thiên (て) |

| 2 | Tin (しな)Lãm (らむ)Tương (さが) | |

Shakkun kana(Mượn huấn 仮 danh) are based on a nativekun'yomireading, one to three characters represent one to three morae.[7]

| Morae | 1 character, complete | 1 character, partial | 2 characters | 3 characters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nữ (め) Mao (け) Muỗi (か) |

Thạch (し) Tích (と) Thị (ち) |

Ô hô (あ) 50 (い) Đáng yêu (え) Nhị nhị (し) Ong âm (ぶ) |

|

| 2 | Kiến (あり) Cuốn (まく) Vịt (かも) |

81 (くく) Thần tiếng nhạc (ささ) | ||

| 3 | Giận (いかり) Hạ (おろし) Xuy (かしき) |

|||

| – | K | S | T | N | P | M | Y | R | W | G | Z | D | B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | A an anh đủ ưởng | Nhưng gì thêm giá hương muỗi già | Tả tá sa tác giả sài sa thảo tán | Quá nhiều hắn đan đà điền tay lập | Kia nam nại Nam Ninh khó bảy tên cá đồ ăn | Bát phương phương phòng nửa bạn lần đậu sóng bà phá mỏng bá cờ vũ sớm giả tốc diệp xỉ | Vạn mạt ma ma ma ma mãn trước thật gian quỷ | Cũng di đêm dương gia dã tám thỉ phòng | Lương lãng lang nhạc la chờ | Cùng hoàn luân | Ta gì hạ | Xã bắn tạ gia xa trang tàng | Đà quá lớn túi | Phạt bà ma ma |

| i1 | Y di lấy dị đã di bắn năm | Khí chi kĩ kỳ xí bỏ tấc cát xử tới | Tử chi chi thủy bốn tư từ tư chí tư tin ti chùa hầu khi ca thơ sư tím tân chỉ chỉ thứ này chết sự chuẩn cơ vi | Biết trí trần ngàn nhũ huyết mao | Nhị hai người ngày nhân ngươi 儞 nhĩ ni bùn nhĩ nhu đan hà tựa nấu chiên | So tất ti tân ngày băng cơm phụ tần cánh tay tránh quỹ | Dân di mỹ tam tham thủy thấy coi ngự | Lý lợi lê lân nhập chiên | Vị vi gọi giếng heo lam | Kĩ chỉ nghệ kỳ nghi kiến | Tự sĩ sĩ tư khi tẫn từ nhĩ nhị nhi hai ngươi | Trì trị mà sỉ ni bùn | Tì mũi di | |

| i2 | Quý kỷ nhớ kỳ gửi kỵ mấy mộc thành | Phi bi phỉ hỏa phì phi thông làm càn bỉ bị bí | Chưa vị đuôi hơi thân thật ki | Nghi nghi nghĩa nghĩ | Bị phì phi càn mi mị | |||||||||

| u | Vũ vũ ô với có mão quạ đến | Lâu chín khẩu luống khổ cưu tới | Tấc cần chu rượu châu châu châu số tạc tê chử | Đều đậu đậu thông truy xuyên tân | Nô nỗ giận nông nùng chiểu túc | Không không bố phụ bộ đắp kinh lịch | Mưu võ vô mô vụ mưu sáu | Từ 喩 du canh | Lưu lưu loại | Cụ ngộ ngung cầu ngu ngu | Chịu thụ thù nho | Đậu đậu đầu nỏ | Phu đỡ phủ văn nhu bộ bộ | |

| e1 | Y y ái giả | Kỳ gia kế hệ giới kết kê | Thế tây tề thế thi lưng bách lại | Đê Thiên Đế đế tay đại thẳng | Di ni bùn cuối năm túc | Sửa lại án xử sai phản biện tệ bệ biến bá bộ biên trọng cách | Bán mặt ngựa nữ | Kéo duyên muốn dao duệ huynh giang cát chi y | Lễ liệt lệ liệt liền | Hồi huệ mặt tiếu | Hạ nha nhã hạ | Là thoan | Đại điền bùn đình truyền điện mà niết đề đệ | Biện liền đừng bộ |

| e2 | Khí đã mao nuôi tiêu | Bế lần bồi 拝 hộ kinh | Mai mễ mê muội mục mắt hải | Nghĩa khí nghi ngại tước | Lần mỗi | |||||||||

| o1 | Ý nhớ với ứng | Cổ cô khô cố hầu cô nhi phấn | Tông tổ tố tô mười nhặt | Đao thổ đấu độ hộ lợi tốc | Nỗ giận nông dã | Phàm phương ôm bằng lần bảo bảo phú trăm phàm tuệ bổn | Mao mẫu mông mộc hỏi nghe | Dùng dung dục đêm | Lộ lậu | Chăng hô xa điểu oán càng ít tiểu đuôi ma nam tự hùng | Ngô ngô hồ ngu sau lung nhi ngộ lầm | Tục | Thổ độ độ nô giận | Phiền bồ phiên phiên |

| o2 | Mình cự đi cư kỵ hứa hư hưng mộc | Sở tắc từng tăng tăng ghét y bối uyển | Ngăn chờ đăng trừng đến đằng mười điểu thường tích | Nãi có thể cười hà | Phương diện quên mẫu văn mậu nhớ chớ vật vọng môn tang thường tảo | Cùng dư bốn nhiều thế hệ cát | Lữ lữ | Này kỳ kỳ ngữ ngự ngự ngưng | Tự tự tặc tồn như cuốc | Đặc đằng đằng chờ nại trừ trữ |

Development

editDue to the major differences between the Japanese language (which waspolysyllabic) and the Chinese language (which wasmonosyllabic) from which kanji came,man'yōganaproved to be very cumbersome to read and write. As stated earlier, since kanji has two different sets of pronunciation, one based on Sino-Japanese pronunciation and the other on native Japanese pronunciation, it was difficult to determine whether a certain character was used to represent its pronunciation or its meaning, i.e., whether it wasman'yōganaor actual kanji, or both.[citation needed] To alleviate the confusion and to save time writing, kanji that were used asman'yōganaeventually gave rise tohiragana,including the now-obsoletehentaigana(変 thể 仮 danh)alternatives, alongside a separate system that becamekatakana.Hiragana developed fromman'yōganawritten in the highlycursivesōsho(Lối viết thảo)style popularly used by women; meanwhile, katakana was developed by Buddhist monks as a form of shorthand, utilizing, in most cases, only fragments (for example, usually the first or last few strokes) ofman'yōganacharacters. In some cases, oneman'yōganacharacter for a given syllable gave rise to a hentaigana that was simplified further to result in the current hiragana character, while a differentman'yōganacharacter was the source for the current katakana equivalent. For example, the hiraganaる(ru)is derived from theman'yōganaLưu,whereas the katakanaル(ru)is derived from theman'yōganaLưu.The multiple alternative hiragana forms for a single syllable were ultimately standardized in 1900, and the rejected variants are now known ashentaigana.

Man'yōganacontinues to appear in some regional names of present-day Japan, especially inKyūshū.[citation needed][8]A phenomenon similar toman'yōgana,calledateji(Đương て tự),still occurs, where words (includingloanwords) are spelled out using kanji for their phonetic value. Examples includeĐều lặc bộ(kurabu,"club" ),Phật lan tây(Furansu,France),A phất lợi thêm(Afurika,Africa)andÁ mễ lợi thêm(America,America).

| – | K | S | T | N | H | M | Y | R | W | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | A | Thêm | Tán | Nhiều | Nại | Tám | Mạt | Cũng | Lương | Cùng | ||

| ア | カ | サ | タ | ナ | ハ | マ | ヤ | ラ | ワ | |||

| i | Y | Cơ | Mấy | Chi | Ngàn | Nhân | So | Tam | Lợi | Giếng | ||

| イ | キ | シ | チ | ニ | ヒ | ミ | リ | ヰ | ||||

| u | Vũ | Lâu | Cần | Châu | Xuyên | Nô | Không | Mưu | Từ | Lưu | ||

| ウ | ク | ス | ツ | ヌ | フ | ム | ユ | ル | ||||

| e | Giang | Giới | Thế | Thiên | Di | Bộ | Nữ | Giang | Lễ | Huệ | ||

| エ | ケ | セ | テ | ネ | ヘ | メ | エ | レ | ヱ | |||

| o | Với | Mình | Tằng | Ngăn | Nãi | Bảo | Mao | Cùng | Lữ | Chăng | ||

| オ | コ | ソ | ト | ノ | ホ | モ | ヨ | ロ | ヲ | |||

| – | Ngươi | |||||||||||

| ン | ||||||||||||

| – | K | S | T | N | H | M | Y | R | W | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | An | Thêm | Tả | Quá | Nại | Sóng | Mạt | Cũng | Lương | Cùng | |

| あ | か | さ | た | な | は | ま | や | ら | わ | ||

| i | Lấy | Cơ | Mấy | Chi | Biết | Nhân | So | Mỹ | Lợi | Vi | |

| い | き | し | ち | に | ひ | み | り | ゐ | |||

| u | Vũ | Lâu | Tấc | Xuyên | Nô | Không | Võ | Từ | Lưu | ||

| う | く | す | つ | ぬ | ふ | む | ゆ | る | |||

| e | Y | Kế | Thế | Thiên | Di | Bộ | Nữ | Giang | Lễ | Huệ | |

| え | け | せ | て | ね | へ | め | 𛀁 | れ | ゑ | ||

| o | Với | Mình | Tằng | Ngăn | Nãi | Bảo | Mao | Cùng | Lữ | Xa | |

| お | こ | そ | と | の | ほ | も | よ | ろ | を | ||

| – | Vô | ||||||||||

| ん | |||||||||||

See also

edit- Syllabogram

- Sōgana– Archaic Japanese syllabary

- Idu script,Korean analogue

References

editCitations

edit- ^Bjarke Frellesvig (29 July 2010).A History of the Japanese Language.Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–15.ISBN978-1-139-48880-8.

- ^Peter T. Daniels (1996).The World's Writing Systems.Oxford University Press. p. 212.ISBN978-0-19-507993-7.

- ^Bentley, John R. (2001). "The origin of man'yōgana".Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies.64(1): 59–73.doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040.ISSN0041-977X.S2CID162540119.

- ^Seeley, Christopher (2000).A History of Writing in Japan.University of Hawaii. pp. 19–23.ISBN9780824822170.

- ^Farris, William Wayne (1998).Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan.University of Hawaii Press. p. 99.ISBN9780824820305.

The writing style of several other inscriptions also betrays Korean influence... Researchers discovered the longest inscription to date, the 115-character engraving on the Inariyama sword, inSaitamain theKanto,seemingly far away from any Korean emigrés. The style that the author chose for the inscription, however, was highly popular in Paekche.

- ^Joshi & Aaron 2006,p. 483.

- ^abAlex de Voogt; Joachim Friedrich Quack (9 December 2011).The Idea of Writing: Writing Across Borders.BRILL. pp. 170–171.ISBN978-90-04-21545-0.

- ^Al Jahan, Nabeel (2017)."The Origin and Development of Hiragana and Katakana".Academia.edu:8.

Works cited

edit- Joshi, R. Malatesha; Aaron, P. G. (2006).Handbook Of Orthography And Literacy.Routledge.ISBN978-0-8058-5467-1.

- Bentley, John R. (2001). "The origin ofman'yōgana".Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies.64(1): 59–73.doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040.JSTOR3657541.S2CID162540119.