Thepharyngeal arches,also known asvisceral arches,are transient structures seen in theembryonic developmentofhumansand othervertebrates,that are recognisable precursors for many structures.[1]Infish,the arches support thegillsand are known as thebranchial arches,or gill arches.

| Pharyngeal arch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Carnegie stage | 11–14 |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | arcus pharyngei |

| MeSH | D001934 |

| TE | arch_by_E5.4.2.0.0.0.2 E5.4.2.0.0.0.2 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

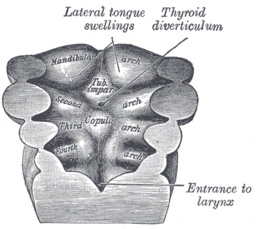

- I–IV: pharyngeal arches

- 1–4:pharyngeal pouches(inside) and/orpharyngeal grooves(outside)

- a:Tuberculum laterale

- b:Tuberculum impar

- c:Foramen cecum

- d:Ductus thyreoglossus

- e:Sinus cervicalis

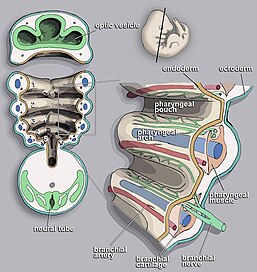

In thehuman embryo,the arches are first seen during the fourth week ofdevelopment.They appear as a series of outpouchings ofmesodermon both sides of the developingpharynx.Thevasculatureof the pharyngeal arches are theaortic archesthat arise from theaortic sac.

Structure

editInhumansand othervertebrates,the pharyngeal arches are derived from all threegerm layers(the primary layers of cells that form duringembryonic development).[2]Neural crest cellsenter these arches where they contribute to features of theskullandfacial skeletonsuch as bone and cartilage.[2]However, the existence of pharyngeal structures before neural crest cells evolved is indicated by the existence of neural crest-independent mechanisms of pharyngeal arch development.[3]The first, most anteriorpharyngeal archgives rise to themandible.The second arch becomes thehyoidand jaw support.[2]In fish, the other posterior arches contribute to the branchial skeleton, which support the gills; in tetrapods the anterior arches develop into components of the ear, tonsils, and thymus.[4]The genetic and developmental basis of pharyngeal arch development is well characterized. It has been shown thatHox genesand other developmental genes such asDLXare important for patterning the anterior/posterior and dorsal/ventral axes of thebranchial arches.[5]Some fish species have a second set of jaws in their throat, known aspharyngeal jaws,which develop using the same genetic pathways involved in oral jaw formation.[6]

Duringembryonic development,a series of pharyngeal arch pairs form. These project forward from the back of the embryo toward the front of the face and neck. Each arch develops its own artery, nerve that controls a distinct muscle group, and skeletal tissue. The arches are numbered from 1 to 6, with 1 being the arch closest to the head of the embryo, and arch 5 existing only transiently.[7]

These grow and join in the ventral midline. The first arch, as the first to form, separates the mouth pit orstomodeumfrom thepericardium.By differential growth the neck elongates and new arches form, so the pharynx has six arches ultimately.

Each pharyngeal arch has acartilaginousstick, amusclecomponent that differentiates from the cartilaginous tissue, an artery, and acranial nerve.Each of these is surrounded bymesenchyme.Arches do not develop simultaneously but instead possess a "staggered" development.

Pharyngeal pouchesform on theendodermalside between the arches, andpharyngeal grooves(or clefts) form from the lateralectodermalsurface of theneckregion to separate the arches.[8]In fish, the pouches line up with the clefts, and these thin segments becomegills.In mammals theendodermandectodermnot only remain intact but also continue to be separated by amesodermlayer.

The development of the pharyngeal arches provides a useful landmark with which to establish the precise stage of embryonic development. Their formation and development corresponds toCarnegie stages10 to 16 inmammals,andHamburger–Hamilton stages14 to 28 in thechicken.Although there are six pharyngeal arches, in humans the fifth arch exists only transiently duringembryogenesis.[9]

First arch

editThefirst pharyngeal arch,alsomandibular arch(corresponding to the first branchial arch of fish), is the first of six pharyngeal arches that develops during the fourth week ofdevelopment.[10]It is located between thestomodeumand thefirst pharyngeal groove.

Processes

editThis arch divides into amaxillary processand amandibular process,giving rise to structures including thebonesof the lower two-thirds of the face and the jaw. The maxillary process becomes themaxilla(orupper jaw,although there are large differences among animals[11]), andpalatewhile the mandibular process becomes themandibleorlower jaw.This arch also gives rise to themuscles of mastication.

Meckel's cartilage

editMeckel's cartilageforms in themesodermof the mandibular process and eventually regresses to form theincusandmalleusof themiddle ear,the anterior ligament of the malleus and thesphenomandibular ligament.Themandibleor lower jaw forms by perichondralossificationusing Meckel's cartilage as a 'template', but the maxillary doesnotarise from direct ossification of Meckel's cartilage.

Derivatives

editThe skeletal elements and muscles are derived from mesoderm of the pharyngeal arches.

Skeletal

- malleusandincusof themiddle ear

- maxillaandmandible

- spine of sphenoid bone

- sphenomandibular ligament

- palatine bone

- squamous part of temporal bone

- anterior ligament of malleus

Muscles

- muscles of mastication(chewing)

- mylohyoid muscle

- digastric muscle,anterior belly

- tensor veli palatini muscle

- tensor tympani muscle

Other

Mucous membraneand glands of theanterior two thirds of the tongueare derived fromectodermandendodermof the arch.

Nerve supply

editThe mandibular and maxillary branches of thetrigeminal nerve(CN V) innervate the structures derived from the corresponding processes of the first arch. In some lower animals, each arch is supplied by two cranial nerves. The nerve of the arch itself runs along the cranial side of the arch and is called post-trematic nerve of the arch. Each arch also receives a branch from the nerve of the succeeding arch called the pre-trematic nerve which runs along the caudal border of the arch. In human embryo, a double innervation is seen only in the first pharyngeal arch. The mandibular nerve is the post-trematic nerve of the first arch andchorda tympani(branch of facial nerve) is the pre-trematic nerve. This double innervation is reflected in the nerve supply of anterior two-thirds oftonguewhich is derived from the first arch.[12]

Blood supply

editThe artery of the first arch is the firstaortic arch,[13]which partially persists as themaxillary artery.

Second arch

editThesecond pharyngeal archorhyoid arch,is the second of fifth pharyngeal arches that develops infetal lifeduring the fourth week of development[10]and assists in forming the side and front of theneck.

Reichert's cartilage

editCartilage in the second pharyngeal arch is referred to as Reichert's cartilage and contributes to many structures in the fully developed adult.[14]In contrast to theMeckel's cartilageof thefirst pharyngeal archit does not constitute a continuous element, and instead is composed of two distinct cartilaginous segments joined by a faint layer ofmesenchyme.[15]Dorsal ends of Reichert's cartilageossifyduring development to form thestapesof themiddle earbefore being incorporated into the middle ear cavity, while the ventral portion ossifies to form the lesser cornu and upper part of the body of thehyoid bone.Caudal to what will eventually become thestapes,Reichert's cartilage also forms thestyloid processof thetemporal bone.The cartilage between thehyoid boneandstyloid processwill not remain as development continues, but itsperichondriumwill eventually form thestylohyoid ligament.

Derivatives

editSkeletal

From the cartilage of the second arch arises

Muscles

- Facial muscles

- Occipitofrontalismuscle

- Platysma

- Stylohyoidmuscle

- Posterior belly ofdigastric muscle

- Stapediusmuscle

- Auricular muscles

Nerve supply

editFacial nerve(CN VII)

Blood supply

editThe artery of the second arch is the secondaortic arch,[13]which gives origin to thestapedial arteryin some mammals but atrophies in most humans.

Muscles derived from the pharyngeal arches

editPharyngeal muscles or Branchial musclesarestriated musclesof the head and neck. Unlikeskeletal musclesthat developmentally come fromsomites,pharyngeal muscles are developmentally formed from the pharyngeal arches.

Most of the skeletal musculature supplied by the cranial nerves (special visceral efferent) is pharyngeal. Exceptions include, but are not limited to, theextraocular musclesand some of the muscles of the tongue. These exceptions receivegeneral somatic efferentinnervation.

First arch

editAll of thepharyngeal musclesthat come from the first pharyngeal arch are innervated by the mandibular divisions of thetrigeminal nerve.[16]These muscles include all themuscles of mastication,the anterior belly of thedigastric,themylohyoid,tensor tympani,andtensor veli palatini.

Second arch

editAll of the pharyngeal muscles of the second pharyngeal arch are innervated by thefacial nerve.These muscles include themuscles of facial expression,the posterior belly of thedigastric,thestylohyoidmuscle, the auricular muscle[16]and thestapediusmuscle of the middle ear.

Third arch

editThere is only one muscle of the third pharyngeal arch, thestylopharyngeus.The stylopharyngeus and other structures from the third pharyngeal arch are all innervated by theglossopharyngeal nerve.

Fourth and sixth arches

editAll the pharyngeal muscles of the fourth and sixth arches are innervated by the superior laryngeal and the recurrent laryngeal branches of thevagus nerve.[16]These muscles include all the muscles of the palate (exception of thetensor veli palatiniwhich is innervated by thetrigeminal nerve), all the muscles of the pharynx (exceptstylopharyngeuswhich is innervated by theglossopharyngeal nerve), and all the muscles of the larynx.

In humans

editIt has been proposed that the five arches in amniotes numbered 1–4 and 6, be re-named as simply 1–5.[17]The fifth arch is seen to be a transient structure and becomes the sixth arch, (the fifth being absent). More is known about the fate of the first arch than the remaining four. The first three contribute to structures above the larynx, whereas the last two contribute to thelarynxandtrachea.

Therecurrent laryngeal nervesare produced from the nerve of arch 5, and the laryngeal cartilages from arches 4 and 5. The superior laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve arises from arch 4. Its arteries, which project between the nerves of the fourth and fifth arches, become the left-side arch of the aorta and the rightsubclavian artery.On the right side, the artery of arch 5 is obliterated while, on the left side, the artery persists as theductus arteriosus;circulatory changes immediately following birth cause the vessel to close down, leaving a remnant, theligamentum arteriosum.During growth, these arteries descend into their ultimate positions in the chest, creating the elongated recurrent paths.[7]

Terminology

editIt has been proposed that the arches be re-named simply as 1–5. The argument is the existence of the fifth arch (and pouch), held to be a transient structure in the embryo.[17][23]

Additional images

edit-

Schematic of developinghuman embryowith first (mandibular), second (hyoid),pharyngeal arches and third arches labelled

See also

editReferences

edit- ^Zbasnik, N; Fish, JL (2023)."Fgf8 regulates first pharyngeal arch segmentation through pouch-cleft interactions".Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.11:1186526.doi:10.3389/fcell.2023.1186526.PMC10242020.PMID37287454.

- ^abcGraham A (2003). "Development of the pharyngeal arches".Am J Med Genet A.119A(3): 251–256.doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.10980.PMID12784288.S2CID28318053.

- ^Graham A, Smith A (2001). "Patterning the pharyngeal arches".BioEssays.23(1): 54–61.doi:10.1002/1521-1878(200101)23:1<54::AID-BIES1007>3.0.CO;2-5.PMID11135309.S2CID10792335.

- ^Kardong KV (2003). "Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution".Third Edition.New York (McGraw Hill).

- ^Depew MJ, Lufkin T, Rubenstein JL (2002)."Specification of jaw subdivisions by Dlx genes".Science.298(5592): 381–385.doi:10.1126/science.1075703.PMID12193642.S2CID10274300.

- ^Fraser GJ, Hulsey D, Bloomquist RF, Uyesugi K, Manley NR, Streelman T (2009). Jernvall J (ed.)."An Ancient Gene Network Is Co-opted for Teeth on Old and New Jaws".PLOS Biology.7(2): 0233–0247.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000031.PMC2637924.PMID19215146.

- ^abLarsen, William J. (1993).Human embryology.New York: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 318–323.ISBN0-443-08724-5.

- ^McKenzie, James C."Lecture 24. Branchial Apparatus".Howard University. Archived fromthe originalon 2003-05-02.Retrieved2007-09-09.

- ^Marino, Thomas A."Text for Pharyngeal Arch Development".Temple University. Archived fromthe originalon 2007-09-09.Retrieved2007-09-09.

- ^abWilliam J. Larsen (2001). Human embryology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.ISBN0-443-06583-7

- ^Higashiyama, Hiroki; Koyabu, Daisuke; Hirasawa, Tatsuya; Werneburg, Ingmar; Kuratani, Shigeru; Kurihara, Hiroki (November 2, 2021)."Mammalian face as an evolutionary novelty".PNAS.118(44): e2111876118.Bibcode:2021PNAS..11811876H.doi:10.1073/pnas.2111876118.PMC8673075.PMID34716275.

- ^Inderbir Sing, G.P Pal-Human Embryology

- ^abMcMinn, R., 1994.Last's anatomy: Regional and applied (9th ed).

- ^Sudhir, Sant, 2008.Embryology for Medical Students 2nd edition

- ^Rodríguez-Vázquez JF (2008)."Morphogenesis of the second pharyngeal arch cartilage (Reichert's cartilage) in human embryos".J. Anat.208(2): 179–189.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00524.x.PMC2100189.PMID16441562.

- ^abcdeSadler, Thomas W. (February 2009).Langman's Medical Embryology.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 366–369.ISBN978-0781790697.

- ^abGraham, Anthony; Poopalasundaram, Subathra (11 Aug 2019)."A reappraisal and revision of the numbering of the pharyngeal arches".J. Anat.235(6): 1019–1023.doi:10.1111/joa.13067.PMC6875933.PMID31402457.

- ^"marshall.edu".Archived fromthe originalon 2009-02-27.Retrieved2007-09-09.

- ^Sadler, Thomas W. (February 2009).Langman's Medical Embryology.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 366–372.ISBN978-0781790697.

- ^Higashiyama H, Kuratani S (2014). "On the maxillary nerve".Journal of Morphology.275(1): 17–38.doi:10.1002/jmor.20193.PMID24151219.S2CID32707087.

- ^abNetter, Frank H.; Cochard, Larry R. (2002).Netter's Atlas of human embryology.Teterboro, N.J: Icon Learning Systems. p. 227.ISBN0-914168-99-1.

- ^abKyung Won Chung (2005).Gross Anatomy (Board Review).Hagerstown, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.ISBN0-7817-5309-0.

- ^Graham, Anthony; Hikspoors, Jill P. J. M.; Anderson, Robert H.; Lamers, Wouter H.; Bamforth, Simon D. (October 2023)."A revised terminology for the pharyngeal arches and the arch arteries".Journal of Anatomy.243(4): 564–569.doi:10.1111/joa.13890.PMC10485586.PMID37248750.

External links

edit- Graham A, Okabe M, Quinlan R (2005)."The role of the endoderm in the development and evolution of the pharyngeal arches".J. Anat.207(5): 479–87.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00472.x.PMC1571564.PMID16313389.