This article has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

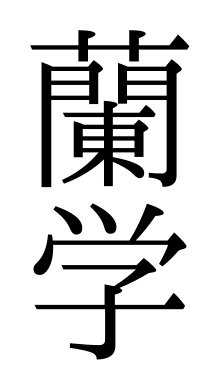

Rangaku(Kyūjitai:Lan học,[a]English:Dutch learning), and by extensionYōgaku(Japanese:Dương học,"Western learning"),is a body of knowledge developed byJapanthrough its contacts with the Dutch enclave ofDejima,which allowed Japan to keep abreast ofWesterntechnologyandmedicinein the period when the country was closed to foreigners from 1641 to 1853 because of theTokugawa shogunate's policy of national isolation (sakoku).

Through Rangaku, some people in Japan learned many aspects of thescientific and technological revolutionoccurring inEuropeat that time, helping the country build up the beginnings of a theoretical and technological scientific base, which helps to explain Japan's success in its radical and speedy modernization following theforced American opening of the country to foreign tradein 1854.[1]

History

editTheDutchtraders atDejimainNagasakiwere the only Europeans tolerated in Japan from 1639 until 1853 (the Dutch had a trading post inHiradofrom 1609 till 1641 before they had to move to Dejima), and their movements were carefully watched and strictly controlled, being limited initially to one yearly trip to give theirhomage to theshōguninEdo.They became instrumental, however, in transmitting to Japan some knowledge of theIndustrialandScientific Revolutionthat was occurring in Europe: In 1720 the ban on Dutch books was lifted and the Japanese purchased and translated scientific books from the Dutch, obtained from them Western curiosities and manufactures (such as clocks, medical instruments, celestial and terrestrial globes, maps and plant seeds) and received demonstrations of Western innovations, including of electrical phenomena, as well as the flight of a hot air balloon in the early 19th century. While other European countries faced ideological and political battles associated with theProtestant Reformation,the Netherlands were afree state,attracting leading thinkers such asRené Descartes.[citation needed]

Altogether, thousands of such books were published, printed, and circulated. Japan had one of the largest urban populations in the world, with more than one million inhabitants inEdo,and many other large cities such asOsakaandKyoto,offering a large, literate market to such novelties. In the large cities some shops, open to the general public, specialized in foreign curiosities.[citation needed]

Beginnings (1640–1720)

editThe first phase of Rangaku was quite limited and highly controlled. After the relocation of the Dutch trading post toDejima,trade as well as the exchange of information and the activities of the remaining Westerners (dubbed "Red-Heads" (kōmōjin)) were restricted considerably. Western books were prohibited, with the exemption of books on nautical and medical matters. Initially, a small group ofhereditaryJapanese–Dutch translators labored in Nagasaki to smooth communication with the foreigners and transmit bits of Western novelties.

The Dutch were requested to give updates of world events and to supply novelties to theshōgunevery year on their tripstoEdo.Finally, the Dutch factories in Nagasaki, in addition to their official trade work in silk and deer hides, were allowed to engage in some level of "private trade". A small, lucrative market for Western curiosities thus developed, focused on the Nagasaki area. With the establishment of a permanent post for a surgeon at the Dutch trading post Dejima, high-ranking Japanese officials started to ask for treatment in cases when local doctors were of no help. One of the most important surgeons wasCaspar Schamberger,who induced a continuing interest in medical books, instruments, pharmaceuticals, treatment methods etc. During the second half of the 17th century high-ranking officials ordered telescopes, clocks, oil paintings, microscopes, spectacles, maps, globes, birds, dogs, donkeys, and other rarities for their personal entertainment and for scientific studies.[2]

Liberalization of Western knowledge (1720–)

editAlthough most Western books were forbidden from 1640, rules were relaxed undershōgunTokugawa Yoshimunein 1720, which started an influx of Dutch books and their translations into Japanese. One example is the 1787 publication ofMorishima Chūryō’sSayings of the Dutch(Hồng mao tạp lời nói,Kōmō Zatsuwa,lit. "Red Hair Chitchat" ),recording much knowledge received from the Dutch. The book details a vast array of topics: it includes objects such asmicroscopesandhot air balloons;discusses Western hospitals and the state of knowledge of illness and disease; outlines techniques forpaintingandprinting with copper plates;it describes the makeup ofstatic electricitygenerators and largeships;and it relates updatedgeographical knowledge.[citation needed]

Between 1804 and 1829, schools opened throughout the country by theShogunate(Bakufu) as well asterakoya(temple schools) helped spread the new ideas further.[citation needed]

By that time, Dutch emissaries and scientists were allowed much more free access to Japanese society. The German physicianPhilipp Franz von Siebold,attached to the Dutch delegation, established exchanges with Japanese students. He invited Japanese scientists to show them the marvels of Western science, learning, in return, much about the Japanese and their customs. In 1824, von Siebold began a medical school in the outskirts of Nagasaki. Soon thisNarutaki-juku(Minh lung thục)grew into a meeting place for about fifty students from all over the country. While receiving a thorough medical education they helped with the naturalistic studies of von Siebold.[citation needed]

Expansion and politicization (1839–)

editThe Rangaku movement became increasingly involved in Japan's political debate over foreign isolation, arguing that the imitating of Western culture would strengthen rather than harm Japan. The Rangaku increasingly disseminated contemporary Western innovations.

In 1839, scholars of Western studies (called lan học giả "rangaku-sha") briefly suffered repression by the Edo shogunate in theBansha no goku(Man xã の ngục,roughly "imprisonment of the society for barbarian studies" )incident, due to their opposition to the introduction of thedeath penaltyagainst foreigners (other than Dutch) coming ashore, recently enacted by theBakufu.The incident was provoked by actions such as theMorrison Incident,in which an unarmed American merchant ship was fired upon under theEdict to Repel Foreign Ships.The edict was eventually repealed in 1842.

Rangaku ultimately became obsolete when Japan opened up during thelast decades of the Tokugawa regime(1853–67). Students were sent abroad, and foreign employees (o-yatoi gaikokujin) came to Japan to teach and advise in large numbers, leading to an unprecedented and rapid modernization of the country.

It is often argued that Rangaku kept Japan from being completely uninformed about the critical phase of Western scientific advancement during the 18th and 19th century, allowing Japan to build up the beginnings of a theoretical and technological scientific base. This openness could partly explain Japan's success in its radical and speedy modernization following the opening of the country to foreign trade in 1854.[citation needed]

Types

editMedical sciences

editFrom around 1720, books on medical sciences were obtained from the Dutch, and then analyzed and translated into Japanese. Great debates occurred between the proponents oftraditional Chinese medicineand those of the new Western learning, leading to waves of experiments anddissections.The accuracy of Western learning made a sensation among the population, and new publications such as theAnatomy(Tàng chí,Zōshi,lit. "Stored Will" )of 1759 and theNew Text on Anatomy(Giải thể sách mới,Kaitai Shinsho,lit. "Understanding [of the] Body New Text" )of 1774 became references. The latter was a compilation made by several Japanese scholars, led bySugita Genpaku,mostly based on the Dutch-languageOntleedkundige Tafelenof 1734, itself a translation ofAnatomische Tabellen(1732) by the German authorJohann Adam Kulmus.

In 1804,Hanaoka Seishūperformed the world's firstgeneral anaesthesiaduring surgery for breast cancer (mastectomy). The surgery involved combining Chinese herbal medicine and Westernsurgerytechniques,[3]40 years before the better-known Western innovations ofLong,WellsandMorton,with the introduction ofdiethyl ether(1846) andchloroform(1847) as general anaesthetics.

In 1838, the physician and scholarOgata Kōanestablished the Rangaku school namedTekijuku.Famous alumni of the Tekijuku includeFukuzawa YukichiandŌtori Keisuke,who would become key players in Japan's modernization. He was the author of 1849'sIntroduction to the Study of Disease(Bệnh học thông luận,Byōgaku Tsūron),which was the first book on Westernpathologyto be published in Japan.[citation needed]

Physical sciences

editSome of the first scholars of Rangaku were involved with the assimilation of 17th century theories in thephysical sciences.This is the case ofShizuki Tadao(ja: Chí trúc trung hùng) an eighth-generation descendant of the Shizuki house of NagasakiDutchtranslators, who after having completed for the first time a systematic analysis of Dutch grammar, went on to translate the Dutch edition ofIntroductio ad Veram Physicamof the British authorJohn Keilon the theories ofNewton(Japanese title:Rekishō Shinsho(Lịch tượng sách mới,roughly: "New Text on Transitive Effects" ),1798). Shizuki coined several key scientific terms for the translation, which are still in use in modern Japanese; for example, "gravity"(Trọng lực,jūryoku),"attraction"(Dẫn lực,inryoku)(as inelectromagnetism), and "centrifugal force"(Xa tâm lực,enshinryoku).A second Rangaku scholar,Hoashi Banri(ja: Phàm đủ vạn dặm), published a manual of physical sciences in 1810 –Kyūri-Tsū(Nghèo lý thông,roughly "On Natural Laws" )– based on a combination of thirteen Dutch books, after learning Dutch from just one Dutch-Japanese dictionary.[citation needed]

Electrical sciences

editElectrical experiments were widely popular from around 1770. Following the invention of theLeyden jarin 1745, similarelectrostatic generatorswere obtained for the first time in Japan from the Dutch around 1770 byHiraga Gennai.Static electricitywas produced by the friction of a glass tube with a gold-plated stick, creating electrical effects. The jars were reproduced and adapted by the Japanese, who called it "Elekiteru"(エレキテル,Erekiteru).As in Europe, these generators were used as curiosities, such as making sparks fly from the head of a subject or for supposed pseudoscientific medical advantages. InSayings of the Dutch,theelekiteruis described as a machine that allows one to take sparks out of the human body, to treat sick parts. Elekiterus were sold widely to the public in curiosity shops. Many electric machines derived from theelekiteruwere then invented, particularly bySakuma Shōzan.[citation needed]

Japan's first electricity manual,Fundamentals of theelekiteruMastered by the Dutch(A Lan đà thủy chế エレキテル cứu lý nguyên,Oranda Shisei Erekiteru Kyūri-Gen)byHashimoto Soukichi(ja: Kiều bổn tông cát), published in 1811, describes electrical phenomena, such as experiments with electric generators, conductivity through the human body, and the 1750 experiments ofBenjamin Franklinwithlightning.[citation needed]

Chemistry

editIn 1840,Udagawa Yōanpublished hisOpening Principles of Chemistry(Xá mật khai tông,Seimi Kaisō),a compilation of scientific books in Dutch, which describes a wide range of scientific knowledge from the West. Most of the Dutch original material appears to be derived fromWilliam Henry’s 1799Elements of Experimental Chemistry.In particular, the book contains a detailed description of theelectric batteryinvented byVoltaforty years earlier in 1800. The battery itself was constructed by Udagawa in 1831 and used in experiments, including medical ones, based on a belief that electricity could help cure illnesses.[citation needed]

Udagawa's work reports for the first time in details the findings and theories ofLavoisierin Japan. Accordingly, Udagawa made scientific experiments and created new scientific terms, which are still in current use in modern scientific Japanese, like "oxidation"(Toan hóa,sanka),"reduction"(Còn nguyên,kangen),"saturation"(Bão hòa,hōwa),and "element"(Nguyên tố,genso).[citation needed]

Optical sciences

editTelescopes

editJapan's firsttelescopewas offered by theEnglishcaptainJohn SaristoTokugawa Ieyasuin 1614, with the assistance ofWilliam Adams,during Saris's mission to open trade between England and Japan. This followed the invention of the telescope by DutchmanHans Lippersheyin 1608 by a mere six years.Refracting telescopeswere widely used by the populace during theEdo period,both for pleasure and for the observation of the stars.

After 1640, the Dutch continued to inform the Japanese about the evolution of telescope technology. Until 1676 more than 150 telescopes were brought to Nagasaki.[4]In 1831, after having spent several months in Edo where he could get accustomed with Dutch wares,Kunitomo Ikkansai(a former gun manufacturer) built Japan's firstreflecting telescopeof theGregoriantype. Kunitomo's telescope had amagnificationof 60, and allowed him to make very detailed studies ofsun spotsand lunar topography. Four of his telescopes remain to this day.[citation needed]

-

Kunitomo'sreflecting telescope,1831

-

Observation of the moon by Kunitomo in 1836

Microscopes

editMicroscopes were invented in the Netherlands during the 17th century, but it is unclear when exactly they reached Japan. Clear descriptions of microscopes are made in the 1720Nagasaki Night Stories Written(Nagasaki dạ thoại thảo,Nagasaki Yawasō)and in the 1787 bookSaying of the Dutch.Although Europeans mainly used microscopes to observe small cellular organisms, the Japanese mainly used them forentomologicalpurposes, creating detailed descriptions ofinsects.[citation needed]

Magic lanterns

editMagic lanterns, first described in the West byAthanasius Kircherin 1671, became very popular attractions in multiple forms in 18th-century Japan.

The mechanism of a magic lantern, called "shadow picture glasses"(Ảnh hội mắt kính,Kagee Gankyō)was described using technical drawings in the book titled Tengu-tsū(Thiên cẩu thông)in 1779.[citation needed]

Mechanical sciences

editAutomata

editKarakuriare mechanizedpuppetsorautomatafromJapanfrom the 18th century to 19th century. The word means "device" and carries the connotations of mechanical devices as well as deceptive ones. Japan adapted and transformed the Western automata, which were fascinating the likes ofDescartes,giving him the incentive for hismechanist theoriesoforganisms,andFrederick the Great,who loved playing with automatons andminiature wargames.

Many were developed, mostly for entertainment purposes, ranging fromtea-servingtoarrow-shootingmechanisms. These ingenious mechanical toys were to become prototypes for the engines of the industrial revolution. They were powered byspringmechanisms similar to those ofclocks.[citation needed]

Clocks

editMechanical clocks were introduced into Japan byJesuitmissionariesorDutchmerchants in the sixteenth century. These clocks were of thelantern clockdesign, typically made ofbrassoriron,and used the relatively primitiveverge and foliotescapement.These led to the development of an original Japanese clock, calledWadokei.[citation needed]

Neither thependulumnor thebalance springwere in use among European clocks of the period, and as such they were not included among the technologies available to the Japanese clockmakers at the start of theisolationist periodinJapanese history,which began in 1641. As the length of an hour changed during winter, Japanese clock makers had to combine two clockworks in one clock. While drawing from European technology they managed to develop more sophisticated clocks, leading to spectacular developments such as the UniversalMyriad year clockdesigned in 1850 by the inventorTanaka Hisashige,the founder of what would become theToshibacorporation.[citation needed]

Pumps

editAir pump mechanisms became popular in Europe from around 1660 following the experiments ofBoyle.In Japan, the first description of avacuum pumpappear inAochi Rinsō(ja: Thanh mà lâm tông)’s 1825Atmospheric Observations(Khí hải quan lan,Kikai Kanran),and slightly later pressure pumps and void pumps appear inUdagawa Shinsai(Vũ điền xuyên trăn trai ( Huyền Chân ))’s 1834Appendix of Far-Western Medical and Notable Things and Thoughts(Xa Tây y phương sự vật và tên gọi khảo phần bổ sung,Ensei Ihō Meibutsu Kō Hoi).These mechanisms were used to demonstrate the necessity of air for animal life and combustion, typically by putting a lamp or a small dog in a vacuum, and were used to make calculations of pressure and air density.[citation needed]

Many practical applications were found as well, such as in the manufacture ofair gunsbyKunitomo Ikkansai,after he repaired and analyzed the mechanism of some Dutch air guns which had been offered to theshōguninEdo.A vast industry of perpetualoil lamps(Vô tận đèn,Mujintō)developed, also derived by Kunitomo from the mechanism of air guns, in which oil was continuously supplied through a compressed air mechanism.[5]Kunitomo developed agricultural applications of these technologies, such as a giant pump powered by anox,to lift irrigation water.

-

Kunitomo's "Aspiration pump driven by an ox" (1810 advertisement)

-

Air gun trigger mechanism

Aerial knowledge and experiments

editThe first flight of ahot air balloonby the brothersMontgolfierin France in 1783, was reported less than four years later by the Dutch in Dejima, and published in the 1787Sayings of the Dutch.

In 1805, almost twenty years later, theSwissJohann Caspar Hornerand thePrussianGeorg Heinrich von Langsdorff,two scientists of theKruzenshternmission that also brought the Russian ambassadorNikolai Rezanovto Japan, made a hot air balloon out of Japanese paper (washi) and made a demonstration of the new technology in front of about 30 Japanese delegates.[6]

Hot air balloons would mainly remain curiosities, becoming the object of experiments and popular depictions, until the development of military usages during the earlyMeiji period.[citation needed]

Steam engines

editKnowledge of thesteam enginestarted to spread in Japan during the first half of the 19th century, although the first recorded attempts at manufacturing one date to the efforts ofTanaka Hisashigein 1853, following the demonstration of a steam engine by the Russian embassy ofYevfimiy Putyatinafter his arrival in Nagasaki on August 12, 1853.

The Rangaku scholarKawamoto Kōmincompleted a book namedOdd Devices of the Far West(Xa tây kỳ khí thuật,Ensei Kiki-Jutsu)in 1845, which was finally published in 1854 as the need to spread Western knowledge became even more obvious withCommodore Perry’sopening of Japanand the subsequent increased contact with industrial Western nations. The book contains detailed descriptions of steam engines and steamships. Kawamoto had apparently postponed the book's publication due to theBakufu's prohibition against the building of large ships.[citation needed]

Geography

editModern geographical knowledge of the world was transmitted to Japan during the 17th century through Chinese prints ofMatteo Ricci's maps as well as globes brought to Edo by chiefs of the VOC trading post Dejima. This knowledge was regularly updated through information received from the Dutch, so that Japan had an understanding of the geographical world roughly equivalent to that of contemporary Western countries. With this knowledge,Shibukawa Shunkaimade the first Japaneseglobein 1690.[citation needed]

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, considerable efforts were made atsurveyingandmappingthe country, usually with Western techniques and tools. The most famous maps using modern surveying techniques were made byInō Tadatakabetween 1800 and 1818 and used as definitive maps of Japan for nearly a century. They do not significantly differ in accuracy with modern ones, just like contemporary maps of European lands.

Biology

editThe description of the natural world made considerable progress through Rangaku; this was influenced by theEncyclopedistsand promoted byvon Siebold(a German doctor in the service of the Dutch at Dejima).Itō Keisukecreated books describing animal species of the Japanese islands, with drawings of a near-photographic quality.

Entomologywas extremely popular, and details about insects, often obtained through the use of microscopes (see above), were widely publicized.[citation needed]

In a rather rare case of "reverse Rangaku" (that is, the science of isolationist Japan making its way to the West), an 1803 treatise on the raising ofsilk wormsand manufacture ofsilk,theSecret Notes onSericulture(Dưỡng tằm bí lục,Yōsan Hiroku)was brought to Europe by von Siebold and translated into French and Italian in 1848, contributing to the development of the silk industry in Europe.

Plants were requested by the Japanese and delivered from the 1640s on, including flowers such as precious tulips and useful items such as thecabbageand thetomato.[citation needed]

Other publications

edit- Automatons:Karakuri Instructional Pattern Notes(Cơ huấn mông giam thảo,Karakuri Kinmō Kagami-Gusa),1730.

- Mathematics:Western-Style Calculation Text(Tây Dương tính thư,Seiyō Sansho).

- Optics:Telescope Production(Xa kính chế tạo,Enkyō Seizō).

- Glass-making:Glass Production(Tiêu tử chế tạo,Garasu Seizō).

- Military:Tactics of the Three Combat Arms(Tam binh đáp cổ biết mấy,Sanpei Takuchiiki),byTakano Chōeiconcerning the tactics of thePrussian Army,1850.

- Description of the method ofamalgamforgold platingin Sōken Kishō(Trang kiếm kỳ thưởng),orTrang kiếm kỳ thưởnginShinjitai,byInaba Shin'emon( đạo diệp tân hữu vệ môn ), 1781.

Aftermath

editCommodore Perry

editWhenCommodore Perryobtained the signature of treaties at theConvention of Kanagawain 1854, he brought technological gifts to the Japanese representatives. Among them was a small telegraph and a smallsteam traincomplete with tracks. These were promptly studied by the Japanese as well.

Essentially considering the arrival of Western ships as a threat and a factor for destabilization, theBakufuordered several of its fiefs to build warships along Western designs. These ships, such as theHōō-Maru,theShōhei-Maru,and theAsahi-Maru,were designed and built, mainly based on Dutch books and plans. Some were built within a mere year or two of Perry's visit. Similarly, steam engines were immediately studied.Tanaka Hisashige,who had made theMyriad year clock,created Japan's first steam engine, based on Dutch drawings and the observation of a Russian steam ship in Nagasaki in 1853. These developments led to theSatsumafief building Japan's first steam ship, theUnkō-Maru( vân hành hoàn ), in 1855, barely two years after Japan's first encounter with such ships in 1853 during Perry's visit.

In 1858, the Dutch officerKattendijkecommented:

There are some imperfections in the details, but I take my hat off to the genius of the people who were able to build these without seeing an actual machine, but only relied on simple drawings.[8]

Last phase of "Dutch" learning

editFollowing Commodore Perry's visit, the Netherlands continued to have a key role in transmitting Western know-how to Japan for some time. The Bakufu relied heavily on Dutch expertise to learn about modern Western shipping methods. Thus, theNagasaki Naval Training Centerwas established in 1855 right at the entrance of the Dutch trading post ofDejima,allowing for maximum interaction with Dutch naval knowledge. From 1855 to 1859, education was directed by Dutch naval officers, before the transfer of the school toTsukijiinTokyo,where English educators became prominent.[citation needed]

The center was equipped with Japan's first steam warship, theKankō Maru,given by the government of theNetherlandsthe same year, which may be one of the last great contributions of the Dutch to Japanese modernization, before Japan opened itself to multiple foreign influences. The future AdmiralEnomoto Takeakiwas one of the students of the Training Center. He was also sent to the Netherlands for five years (1862–1867), with several other students, to develop his knowledge of naval warfare, before coming back to become the admiral of theshōgun's fleet.[citation needed]

Enduring influence of Rangaku

editScholars of Rangaku continued to play a key role in the modernization of Japan. Scholars such asFukuzawa Yukichi,Ōtori Keisuke,Yoshida Shōin,Katsu Kaishū,andSakamoto Ryōmabuilt on the knowledge acquired during Japan's isolation and then progressively shifted the main language of learning fromDutchtoEnglish.

As these Rangaku scholars usually took a pro-Western stance, which was in line with the policy of theShogunate(Bakufu) but against anti-foreign imperialistic movements, several were assassinated, such asSakuma Shōzanin 1864 andSakamoto Ryōmain 1867.[citation needed]

Notable scholars

edit- Arai Hakuseki(Tân giếng bạch thạch,1657–1725), author ofSairan IgenandSeiyō Kibun

- Aoki Kon'yō(Thanh mộc côn dương,1698–1769)

- Maeno Ryōtaku(Trước dã lương trạch,1723–1803)

- Yoshio Kōgyū(Cát hùng trâu cày,1724–1800)

- Ono Ranzan(Tiểu dã lan sơn,1729–1810), author ofBotanical Classification(Bản Thảo Cương Mục khải mông,Honzō Kōmoku Keimō).

- Hiraga Gennai(Bình hạ nguyên nội,1729–79) proponent of the "Elekiter"

- Gotō Gonzan(Sau đằng Cấn Sơn)

- Kagawa Shūan(Hương xuyên tu am)

- Sugita Genpaku(Sam điền huyền bạch,1733–1817) author ofNew Treatise on Anatomy(Giải thể sách mới,Kaitai Shinsho).

- Asada Gōryū(Ma điền mới vừa lập,1734–99)

- Motoki Ryōei(Bổn mộc lương vĩnh,1735–94), author ofUsage of Planetary and Heavenly Spheres(Thiên địa nhị cầu cách dùng,Tenchi Nikyū Yōhō)

- Shiba Kōkan(Tư Mã giang hán,1747–1818), painter.

- Shizuki Tadao(Chí trúc trung hùng,1760–1806), author ofNew Book on Calendar Phenomena(Lịch tượng sách mới,Rekishō Shinsho),1798 and translator ofEngelbert Kaempfer'sSakokuron.

- Hanaoka Seishū(Hoa cương thanh châu,1760–1835), first physician who performed surgery using generalanaesthesia.

- Takahashi Yoshitoki(Cao kiều đến khi,1764–1804)

- Motoki Shōei(Bổn mộc chính vinh,1767–1822)

- Udagawa Genshin(Vũ điền xuyên Huyền Chân,1769–1834), author ofNew Volume on Public Welfare(Cuộc sống giàu có tân biên,Kōsei Shinpen).

- Aoji Rinsō(Thanh mà lâm tông,1775–1833), author ofStudy of the Atmosphere(Khí hải quan lan,Kikai Kanran),1825.

- Hoashi Banri(Phàm đủ vạn dặm,1778–1852), author ofPhysical Sciences(Cứu lý thông,Kyūri Tsū).

- Takahashi Kageyasu(Cao kiều cảnh bảo,1785–1829)

- Matsuoka Joan(Tùng cương thứ am)

- Udagawa Yōan(Vũ điền xuyên đa am,1798–1846), author ofBotanica Sutra(Bồ nhiều ni kha kinh,Botanika Kyō,using theLatin"botanica"inateji)andChemical Sciences(Xá mật khai tông,Seimi Kaisō)

- Itō Keisuke(Y đằng khuê giới,1803–1901), author of Western Plant Taxonomy(Âu Châu thảo mộc danh sơ,Taisei Honzō Meiso)

- Takano Chōei(Cao dã trường anh,1804–50), physician, dissident, co-translator of a book on the tactics of thePrussian Army,Tactics of the Three Combat Arms(Tam binh đáp cổ biết mấy,Sanpei Takuchiiki),1850.

- Ōshima Takatō(Đại đảo cao nhậm,1810–71), engineer — established the first western style blast furnace and made the first Western-style cannon in Japan.

- Kawamoto Kōmin(Xuyên bổn hạnh dân,1810–71), author ofStrange Machines of the Far West(Xa tây kỳ khí thuật,Ensei Kikijutsu),completed in 1845, published in 1854.

- Ogata Kōan(Tự phương hồng am,1810–63), founder of theTekijuku,and author ofIntroduction toPathology(Bệnh học thông luận,Byōgaku Tsūron),Japan's first treatise on the subject.

- Sakuma Shōzan(Tá lâu gian tượng sơn,1811–64)

- Hashimoto Sōkichi(Kiều bổn tông cát)

- Hazama Shigetomi(Gian trọng phú)

- Hirose Genkyō(Quảng lại nguyên cung), author ofScience Compendium(Lý học lược thuật trọng điểm,Rigaku Teiyō).

- Takeda Ayasaburō(Võ điền phỉ Tam Lang,1827–80), architect of the fortress ofGoryōkaku

- Ōkuma Shigenobu(Đại ôi trọng tin,1838–1922)

- Yoshio Kōgyū(Cát hùng trâu cày,1724–1800), translator, collector and scholar

See also

editNotes

edit- ^Erlita Tantri (Jun 2012)."The Dutch Science (Rangaku) and its Influence on Japan".Jurnal Ka gian Wilayah.Indonesian Institute of Sciences.3(2): 141-158.doi:10.14203/jkw.v3i2.276

- ^W Michel,Medicine and Allied Sciences in the Cultural Exchange between Japan and Europe in the Seventeenth Century.In: Hans Dieter Ölschleger (Hrsg.):Theories and Methods in Japanese Studies. Current State & Future Developments.Papers in Honor ofJosef Kreiner.Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Unipress, Göttingen 2007,ISBN978-3-89971-355-8,S. 285–302pdf.

- ^"The first use of general anaesthesia probably dates to early nineteenth century Japan. On 13 October 1804, Japanese doctor Seishu Hanaoka (1760–1835) surgically removed a breast tumor under general anaesthesia. His patient was a 60-year-old woman named Kan Aiya."Source

- ^Wolfgang Michel,On Japanese Imports of Optical Instruments in the Early Edo-Era. Yōgaku - Annals of the History of Western Learning in Japan,Vol. 12 (2004), pp. 119-164[1].

- ^Seeing and Enjoying Technology of Edo,p. 25.

- ^Ivan Federovich Kruzenshtern. "Voyage round the world in the years 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806, on orders of his Imperial Majesty Alexander the First, on the vesselsNadezhdaandNeva".

- ^"Papier-mache terrestrial globe - National Museum of Nature and Science".

- ^Kattendijke,1858, quoted inSeeing and Enjoying Technology of Edo,p. 37.

References

edit- Seeing and Enjoying Technology of Edo(Thấy て lặc しむ giang hộ の テクノロジー), 2006,ISBN4-410-13886-3(Japanese)

- The Thought-Space of Edo(Giang hộ の tư tưởng không gian) Timon Screech, 1998,ISBN4-7917-5690-8(Japanese)

- Glimpses of medicine in early Japanese-German intercourse.In: International Medical Society of Japan (ed.): The Dawn of Modern Japanese Medicine and Pharmaceuticals -The 150th Anniversary Edition of Japan-German Exchange. Tokyo: International Medical Society of Japan (IMSJ), 2011, pp. 72–94. (ISBN978-4-9903313-1-3)

External links

edit- Spackman, Chris,Encyclopedia of Japanese History,Open History.

- Rangaku World maps,Japan: Kyoto U, archived fromthe originalon 2004-08-29.

- Rangaku Kotohajime: Dawn of Western Science in Japan,The Human Brain project, archived fromthe originalon 2009-04-17.

- Further reading/bibliography,ENG, UK: East Asia Institute,University of Cambridge,archived fromthe originalon 2007-08-09.