Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev[a](17 March 1938 – 6 January 1993) was a Soviet-born ballet dancer and choreographer. Nureyev is widely regarded as the preeminent male ballet dancer of his generation as well as one of the greatest ballet dancers of all time.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Rudolf Nureyev | |

|---|---|

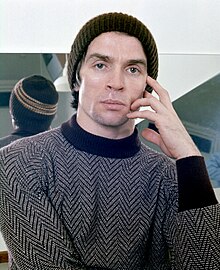

Nureyev in 1973 | |

| Born | Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev 17 March 1938 NearIrkutsk,Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | 6 January 1993(aged 54) Levallois-Perret,France |

| Cause of death | AIDS-related complications |

| Resting place | Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Cemetery,Paris, France |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Kirov Ballet School |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1958–1992 |

| Height | 173 cm (5 ft 8 in) |

| Partners |

|

| Website | nureyev.org |

Nureyev was born on aTrans-Siberiantrain nearIrkutsk,Siberia, Soviet Union, to aTatarfamily. He began his early career with the company that in the Soviet era was called theKirov Ballet(now called by its original name, the Mariinsky Ballet) inLeningrad.Hedefectedfrom theSoviet Unionto the West in 1961, despiteKGBefforts to stop him.[8]This was the first defection of a Soviet artist during theCold War,and it created an international sensation. He went on to dance withThe Royal Balletin London and from 1983 to 1989 served as director of theParis Opera Ballet.Nureyev was also a choreographer serving as the chief choreographer of the Paris Opera Ballet. He produced his own interpretations of numerous classical works,[9]includingSwan Lake,GiselleandLa Bayadère.[10]

Early life

editNureyev's grandfather, Nurakhmet Fazlievich Fazliev, and his father, Khamit Fazleevich Nureyev (1903–1985), were fromAsanovoin the Sharipov volost of the Ufa District of theUfa Governorate(now theUfa Districtof theRepublic of Bashkortostan). His mother, Farida Agliullovna Nureyeva (Agliullova) (1907–1987), was born in the village of Tatarskoye Tyugulbaevo, Kuznechikhinsky volost,Kazan Governorate(nowAlkeyevsky Districtof theRepublic of Tatarstan).

Nureyev was born on aTrans-Siberian trainnear Irkutsk, Siberia, while his mother Farida was travelling toVladivostok,where his father Khamet, aRed Armypolitical commissar, was stationed.[11]He was raised as the only son with three older sisters in aTatar Muslimfamily.[12][13][14]In his autobiography, Nureyev noted about his Tatar heritage: "My mother was born in the beautiful ancient city ofKazan.We are Muslims. Father was born in a small village nearUfa,the capital of theRepublic of Bashkiria.Thus, on both sides our relatives are Tatars andBashkirs.I cannot define exactly what it means to me to be a Tatar, and not a Russian, but I feel this difference in myself. Our Tatar blood flows somehow faster and is always ready to boil ".[15]

Career

editEducation at Vaganova Academy

editWhen his mother took Nureyev and his sisters into a performance of the balletSong of the Cranes,he fell in love with dance.[11]As a child, he was encouraged to dance in Bashkir folk performances and his precocity was soon noticed by teachers who encouraged him to train inLeningrad(now Saint Petersburg). On a tour stop in Moscow with a local ballet company, Nureyev auditioned for theBolshoiballet company and was accepted. However, he felt that theMariinsky Balletschool was the best, so he left the local touring company and bought a ticket to Leningrad.[16]

Owing to the disruption of Soviet cultural life caused by World War II, Nureyev was unable to enroll in a major ballet school until 1955, aged 17, when he was accepted by theVaganova Academy of Russian Balletof Leningrad, the associate school of the Mariinsky Ballet. The ballet masterAlexander Ivanovich Pushkintook an interest in him professionally and allowed Nureyev to live with him and his wife.[17]

Principal with Kirov Ballet

editUpon his graduation in 1958, Nureyev joined the Kirov Ballet (now Mariinsky). He moved immediately beyond the corps level, and was given solo roles as a principal dancer from the outset.[2]Nureyev regularly partnered withNatalia Dudinskaya,the company's senior ballerina and wife of its director,Konstantin Sergeyev.Dudinskaya, who was 26 years his senior, first chose him as her partner[17]in the balletLaurencia.

Before long, Nureyev became one of the Soviet Union's best-known dancers. From 1958 to 1961, in his three years with the Kirov, he danced 15 roles, usually opposite his partner,Ninel Kurgapkina,with whom he was very well paired, although she was almost a decade older than he was.[18]Nureyev and Kurgapkina were invited to dance at a gathering atKhrushchev'sdacha,[17]and in 1959 they were allowed to travel outside the Soviet Union, dancing inViennaat the International Youth Festival. Not long after, he was told by the Ministry of Culture that he would not be allowed to go abroad again.[19]In one memorable incident, Nureyev interrupted a performance ofDon Quixotefor 40 minutes, insisting on dancing in tights and not in the customary trousers. He relented in the end, but his preferred dress code was adopted in later performances.[17]

Defection at Paris airport

editBy the late 1950s, Nureyev had become a sensation in the Soviet Union. Though Nureyev's rebellious character and non-conformist attitude made him an unlikely candidate for the tour with the Kirov Ballet, it became more essential he join the tour which the Soviet government considered crucial to its ambitions to demonstrate its "cultural supremacy" over the West.

Furthermore, tensions were growing between Nureyev and the Kirov's artistic director Konstantin Sergeyev, who was also the husband of Nureyev's former dance partner Natalia Dudinskaya.[20]After a representative of the French tour organisers saw Nureyev dance in Leningrad in 1960, the French organisers urged Soviet authorities to let him dance in Paris, and he was allowed to go.[17]

In Paris, his performances electrified audiences and critics. Oliver Merlin inLe Mondewrote,

I will never forget his arrival running across the back of the stage, and his catlike way of holding himself opposite the ramp. He wore a white sash over anultramarinecostume, had large wild eyes and hollow cheeks under a turban topped with a spray of feathers, bulging thighs, immaculate tights. This was already Nijinsky inFirebird.[21]

Nureyev was seen to have broken the rules about mingling with foreigners and reportedly frequentedgay barsin Paris, which alarmed the Kirov's management[22]and theKGBagents observing him. The KGB wanted to send him back to the Soviet Union. On 16 June 1961 when the Kirov company gathered atLe Bourget Airportin Paris to fly to London, Sergeyev took Nureyev aside and told him that he must return to Moscow for a special performance in theKremlin,rather than go on to London with the rest of the company. Nureyev became suspicious and refused.

Next he was told that his mother had fallen severely ill and he needed to go home immediately to see her.[23]Nureyev refused again, believing that on return to the USSR he was likely to be imprisoned. With the help of French police and a Parisian socialite friend, Clara Saint, who had been engaged to Vincent Malraux, the son of the French Minister of Culture,André Malraux,[24]Nureyev escaped his KGB minders and asked for asylum. Sergeyev and the KGB tried to dissuade him, but he chose to stay in Paris.

Within a week, he was signed by theGrand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevasand performedThe Sleeping BeautywithNina Vyroubova.

On a tour of Denmark he metErik Bruhn,soloist at theRoyal Danish Ballet.[25]Bruhn became his lover, his closest friend and his protector until Bruhn's death in 1986.[26]He and Bruhn both appeared as guest dancers with the newly formedAustralian Balletat Her Majesty's Theatre, Sydney in December 1962.

Soviet authorities made Nureyev's father, mother, and dance teacher Pushkin write letters to him, urging him to return, without effect.[17]Although he petitioned the Soviet government for many years to be allowed to visit his mother, he was not allowed to do so until 1987, when his mother was dying andMikhail Gorbachevconsented to the visit.

In 1989, he was invited to dance the role ofJamesinLa Sylphidewith the Mariinsky Ballet at theMariinsky TheatreinLeningrad.[27]The visit gave him the opportunity to see many of the teachers and colleagues he had not seen since his defection.[28]

The Royal Ballet

editPrincipal dancer

editDameNinette de Valoisoffered him a contract to joinThe Royal Balletas Principal Dancer. During his time at the company, however, many critics became enraged as Nureyev made substantial changes to the productions ofSwan LakeandGiselle.[29]Nureyev stayed with the Royal Ballet until 1970, when he was promoted to Principal Guest Artist, enabling him to concentrate on his increasing schedule of international guest appearances and tours. He continued to perform regularly with The Royal Ballet until committing his future to theParis Opera Balletin the 1980s.

Fonteyn and Nureyev

editNureyev's first appearance with prima ballerinaDame Margot Fonteynwas in a ballet matinée organised by The Royal Ballet:Giselle,21 February 1962.[30]The event was held in aid of theRoyal Academy of Dance,a classical ballet teaching organisation of which she was president. He dancedPoème Tragique,a solo choreographed byFrederick Ashton,and theBlack Swanpas de deuxfromSwan Lake.They were so well received that Fonteyn and Nureyev proceeded to form a partnership that endured for many years. They premieredRomeo and Julietfor the company in 1965.[31]Fans of the duo would tear up their programmes to make confetti to throw at the dancers. Nureyev and Fonteyn sometimes did more than 20curtain calls.[30][32]A film of this performance was made in 1966 and is available on DVD.

On 11 July 1967, Fonteyn and Nureyev, after performing in San Francisco, were arrested on nearby roofs, having fled during a police raid on a home in theHaight-Ashburydistrict. They were bailed out, and charges of disturbing the peace and visiting a place where marijuana was used were dropped later that day for lack of sufficient evidence.[33]

Other international appearances

editAmong many appearances in North America, Nureyev developed a long-lasting connection with the National Ballet of Canada, appearing as a guest artist on many occasions. In 1972, he staged a spectacular new production ofSleeping Beautyfor the company, with his own additional choreography augmenting that of Petipa. The production toured widely in the U.S. and Canada after its initial run in Toronto, one performance of which was televised live and subsequently issued on video.

Among the National Ballet's ballerinas, Nureyev most frequently partnered withVeronica TennantandKaren Kain.In 1975 Nureyev worked extensively with American Ballet Theatre resurrectingLe Corsairewith Gelsey Kirkland. He recreatedSleeping Beauty,Swan Lake,andRamondawith Cynthia Gregory. Gregory and Brun joined Nureyev in a pas des trois from the little-knownAugust BournonvilleballetLa Ventana.[34]

Director of the Paris Opera Ballet

editIn January 1982,Austriagranted Nureyev citizenship, ending more than twenty years ofstatelessness.[35][36]In 1983, he was appointed director of theParis Opera Ballet,where, as well as directing, he continued to dance and to promote younger dancers. He remained there as a dancer and chief choreographer until 1989. Among the dancers he mentored wereSylvie Guillem,Isabelle Guérin,Manuel Legris,Elisabeth Maurin,Élisabeth Platel,Charles Jude, andMonique Loudières.

His artistic directorship of the Paris Opera Ballet was a great success, lifting the company out of a dark period. His version ofSleeping Beautyremains in the repertoire and was revived and filmed with his protégéManuel Legrisin the lead.

Despite advancing illness towards the end of his tenure, he worked tirelessly, staging new versions of old standbys and commissioning some of the most ground-breaking choreographic works of his time. His ownRomeo and Julietwas a popular success. When he was sick towards the end of his life, he worked on a final production ofLa Bayadèrewhich closely follows theMariinsky Balletversion he danced as a young man.

Final years

editWhenAIDSappeared in France's news around 1982, Nureyev took little notice. The dancer testedpositiveforHIVin 1984, but for several years he simply denied that anything was wrong with his health. However, by the late 1980s his diminished capabilities disappointed his admirers who had fond memories of his outstanding prowess and skill.[37]Nureyev began a marked decline only in the summer of 1991 and entered the final phase of the disease in the spring of 1992.[38]

In March 1992, living with advanced AIDS, he visitedKazanand appeared as a conductor in front of the audience at Musa Cälil Tatar Academic Opera and Ballet Theater, which now presents the Rudolf Nureyev Festival inTatarstan.[39][40]Returning to Paris, with a high fever, he was admitted to the hospital Notre Dame du Perpétuel Secours inLevallois-Perret,a suburb northwest of Paris, and was operated on forpericarditis,an inflammation of the membranous sac around the heart. At that time, what inspired him to fight his illness was the hope that he could fulfill an invitation to conductProkofiev'sRomeo and Julietat anAmerican Ballet Theatrebenefit on 6 May 1992 at theMetropolitan Opera Housein New York. He did so and was elated at the reception.[38]

In July 1992, Nureyev showed renewed signs of pericarditis but determined to forswear further treatment. His last public appearance was on 8 October 1992, at the premiere atPalais Garnierof a new production ofLa Bayadèrethat he choreographed afterMarius Petipafor theParis Opera Ballet.Nureyev had managed to obtain a photocopy ofLudwig Minkus' original score when in Russia in 1989.[41]The ballet was a personal triumph although the gravity of his condition was evident. The French Culture Minister,Jack Lang,presented him that evening on stage with France's highest cultural award, theCommandeurde l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.[38]

Death

editNureyev re-entered the hospital Notre Dame du Perpétuel Secours in Levallois-Perret on 20 November 1992 and remained there until his death from AIDS complications at age 54 on 6 January 1993. His funeral was held in the marble foyer of theParis Garnier Opera House.Many paid tribute to his brilliance as a dancer. One such tribute came fromOleg Vinogradovof the Mariinsky Ballet, stating: "What Nureyev did in the West, he could never have done here."[42]

Nureyev's grave, at the Russian cemetery inSainte-Geneviève-des-Boisnear Paris, features a tomb draped in a mosaic of an Oriental carpet, aKelim.Nureyev was an avid collector of beautiful carpets and antique textiles.[38][39][43]As his coffin was lowered into the ground, music from the last act ofGisellewas played and his ballet shoes were cast into the grave along with white lilies.[44]

Tributes

editAfter so many years of having been denied a place in the Mariinsky Ballet's history, Nureyev's reputation was restored.[42]His name was re-entered in the history of the Mariinsky, even though he danced there for only three years. Some of his personal effects were placed on display at the theatre museum in what is nowSt. Petersburg.[42]A rehearsal room was named in his honour at the famed Vaganova Academy.[42]As of October 2013, theCentre National du Costume de Scènehas a permanent collection of Nureyev's costumes "that offers visitors a sense of his exuberant, vagabond personality and passion for all that was rare and beautiful."[45]In 2015, he was inducted into theLegacy Walk.[46]

Since his death in 1993, the Paris Opera has instituted a tradition of presenting an evening of dance homage to Nureyev every 10 years. Because he was born in March, these performances have been given on 20 March 2003, 6 March 2013 and 18 March 2023.[47]Peers of Nureyev who speak about and remember him, likeMikhail Baryshnikov,are often deeply touched.[48][49]

On 7 November 2018, a monument honouring Nureyev was unveiled at the square near the Musa Cälil Tatar Academic Opera and Ballet Theater in Kazan. The monument was designed byZurab Tsereteliand its unveiling ceremony was attended by President of TatarstanRustam Minnikhanov,state adviser of the Republic of TatarstanMintimer Shaimievand mayor of KazanIlsur Metshin.At a speech in the unveiling event, Minnikhanov stated "I think, not only for the Republic, Rudolf Nureyev is an international value. Such people are born once in a hundred years."[50][51][52]

Repertoire

editA selected list of ballet performances, ballet productions and original ballets.[53]

- Laurencia– Frondoso

- Swan Lake– Prince Siegfried, Rothbart

- The Nutcracker– Drosselmeyer, Prince

- Sleeping Beauty– Blue Bird, Prince Florimund (Desiree)

- Marguerite and Armand– Armand

- La Bayadere– Solor

- Raymonda– Four Knights, Jean de Brienne

- Giselle– Count Albert

- Don Quixote– Basilio

- Le Corsaire– a slave

- Romeo and Juliet– Romeo, Mercutio

- La Sylphide– James

- Petrushka– Petrushka

- Le Spectre de la rose– The Spirit of the Rose

- Scheherazade– Golden Slave

- Afternoon Rest of the Faun– Faun

- Apollo– Apollo

- The Young Man and Death– Youth

- Prodigal Son

- Phaedra's Dream,choreographed byMartha Grahamas the role of Hippolyte.

- Paradise Lost,choreographed byRoland Petit

- Les Sylphides– Youth

- HamletbyRobert Helpmann– Hamlet

- Cinderella,choreographed and produced Nureyev.

- Gayane,choreographed byNina Anisimova(solo performance).

- Pierrot Lunairechoreographed byGlen Tetleyas the role of Pierrot.

- Lucifer,choreographed by Martha Graham – Lucifer

- IdiotbyValery Panov– Prince Myshkin

- Coppélia

- Songs of a Wayfarer,choreographed byMaurice Béjart

- The Rite of Spring

- The Moor's Pavane– Othello

- Orpheus,choreographed byGeorge Balanchineas the role of Orpheus.

- Songs Without Words,choreographed byHans van Manen

- The Tempest,choreographed by Nureyev as the role of Prospero.

- Night Journey,choreographed by Martha Graham as the role of Oedipus.

- The Scarlet Letter,choreographed by Martha Graham as the role of Rev. Dimsdale.

- Notre Dame of Paris,choreographed by Roland Petit as the role of Quasimodo.

- La Esmeralda,choreographed by Vakhtang Chabukiani.

- "Ecuatorial", choreographed by Martha Graham, lead withYuriko Kimura

Dance partnerships

editYvette Chauviréof the Paris Opera Ballet often danced with Nureyev; he described her as a "legend".[54](Chauviré attended his funeral with French dancer and actressLeslie Caron.)[55]

At the Royal Ballet, Nureyev andMargot Fonteynbecame long-standing dance partners. Nureyev once said of Fonteyn, who was 19 years older than him, that they danced with "one body, one soul". Together Nureyev and Fonteyn premieredSir Frederick Ashton's balletMarguerite and Armand,a ballet danced toLiszt'sPiano Sonata in B minor,which became their signature piece.Kenneth MacMillanwas forced to allow them to premiere hisRomeo and Juliet,which was intended for two other dancers,Lynn SeymourandChristopher Gable.[56]Films exist of their partnership inLes Sylphides,Swan Lake,Romeo and Juliet,and other roles. They continued to dance together for many years after Nureyev's departure from the Royal Ballet. Their last performance together was inBaroque Pas de Troison 16 September 1988 when Fonteyn was 69, Nureyev was aged 50, withCarla Fracci,aged 52, also starring.

He celebrated another long-time partnership withEva Evdokimova.They first appeared together inLa Sylphide(1971) and in 1975 he selected her as hisSleeping Beautyin his staging forLondon Festival Ballet.Evdokimova remained his partner of choice for many guest appearances and tours across the globe with "Nureyev and Friends" for more than fifteen years.

During his American stage debut in 1962, Nureyev also partnered withSonia Arovaat New York City'sBrooklyn Academy of Music.In collaboration withRuth Page'sChicago Opera Ballet,they performed the grand pas de deux fromDon Quixote.[57][58][59][60]

Legacy

editAs an influence

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Nureyev and the Joffrey Balletin PBS'sTribute to Nijinskydancing: Petrouchka(Fokine) Le Spectre de la Rose(Fokine) L'Apres midi d'un Faune(Nijinsky) in 1981 |

Nureyev was above all a stickler for classical technique, and his mastery of it made him a model for an entire generation of dancers. If the standard of male dancing rose so visibly in the West after the 1960s, it was largely because of Nureyev's inspiration.[2]

Nureyev's influence on the world of ballet changed the perception of male dancers; in his own productions of the classics the male roles received much more choreography.[62]Another important influence was his crossing the borders between classical ballet and modern dance by performing both.[63]Today it is normal for dancers to receive training in both styles, but Nureyev was the originator and excelled in modern and classical dance. He went out of his way to work with modern dance great,Martha Graham,and she created a work specially for him.[64]WhileGene Kellyhad done much to combine modern and classical styles in film, he came from a more Modern Dance influenced "popular dance" environment, while Nureyev made great strides in gaining acceptance of Modern Dance in the "Classical Ballet" sphere.[64]

Nureyev's charisma, commitment and generosity were such that he did not just pass on his knowledge.[65]He personified the school of life for a dancer. Several dancers, who were principals with the Paris Opera Ballet under his direction, went on to become ballet directors themselves inspired to continue Nureyev's work and ideas. Manuel Legris was director of theVienna State Balletand now directsLa Scala Theatre Ballet,Laurent Hilairewas ballet director of theStanislavski Theatre of Moscowand is now director ofBavarian State Balletat Munich, and Charles Jude was ballet director of theGrand Théâtre de Bordeaux.[65]

Mikhail Baryshnikov,the other great dancer who like Nureyev defected to the West, holds Nureyev in high regard. Baryshnikov said in an interview that Nureyev was an unusual man in all respects, instinctive, intelligence, constant curiosity, and extraordinary discipline, that was his goal of life and of course love in performing.[48][66]

Technique and quest for perfection

editNureyev had a late start to ballet and had to perfect his technique to be a success.John Tooleywrote that Nureyev grew up very poor and had to make up for three to five years in ballet education at a high-level ballet school, giving him a decisive impetus to acquire the maximum of technical skills[67]and to become the best dancer working on perfection during his whole career.[68]The challenge for all dancers whom Nureyev worked with was to follow suit and to share his total commitment for dance. Advocates to describe the Nureyev phenomenon precisely are John Tooley, former general director of the London'sRoyal Opera House,Pierre Bergé,former president of Opéra Bastille, venue of the Paris Opera Ballet (in addition to the Palais Garnier) andManuel Legris,principal dancer with the Paris Opera Ballet nominated by Nureyev in New York.

Nureyev put it like this: "I approach dancing from a different angle than those who begin dancing at eight or nine. Those who have studied from the beginning never question anything."[69]Nureyev entered the Vaganova Ballet Academy at the age of 17 staying there for only three years compared to dancers who usually become principal dancers after entering the Vaganova school at nine and go through the full nine years of dance education. Nureyev was a contemporary ofVladimir Vasiliev,who was the premiere dancer at the Bolshoi. Later, Nureyev was a predecessor toMikhail Baryshnikovat the Kirov Ballet, now the Mariinsky Theater. Unlike Vasiliev and Baryshnikov, Nureyev did not build his reputation on success in international ballet competitions, but rather through his performances and popular image.

Paradoxically, both Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov became masters of perfection in dance.[67][1][70]Dance and life was one and the same, Pierre Bergé said about Nureyev: "He was a dancer like any other dancer. It is extraordinary to have 19 points out of 20. It is extremely rare to have 20 out of 20. However, to have 21 out of 20 is even much rarer. And this was the situation with Nureyev."[71][72]Legris said: "Rudolf Nureyev was a high-speed train (he was a TGV)."[73][74]Working with Nureyev involved having to surpass oneself and "stepping on it."[75]

Personal life

editNureyev did not have much patience with rules, limitations and hierarchical order and had at times a volatile temper.[76]He was apt to throw tantrums in public when frustrated.[77]His impatience mainly showed itself when the failings of others interfered with his work.

He socialised withRingo Starr,Gore Vidal,Freddie Mercury,Jackie Kennedy Onassis,Mick Jagger,Liza Minnelli,Andy Warhol,Lee RadziwillandTalitha Pol,Jessye Norman,Tamara Toumanovaand occasionally visited the New York discothequeStudio 54in the late 1970s, but developed an intolerance for celebrities.[78] He kept up old friendships in and out of the ballet world for decades, and was considered to be a loyal and generous friend.[79]

Most ballerinas with whom Nureyev danced, includingAntoinette Sibley,Cynthia Gregory,Gelsey KirklandandAnnette Page,paid tribute to him as a considerate partner. He was known as extremely generous to many ballerinas, who credit him with helping them during difficult times. In particular, the Canadian ballerinaLynn Seymour– distressed when she was denied the opportunity to premiereMacMillan'sRomeo and Juliet– says that Nureyev often found projects for her even when she was suffering from weight problems and depression and thus had trouble finding roles.[80]

Depending on the source, Nureyev is described as either bisexual,[81][82]as he did have heterosexual relationships as a younger man, or homosexual.[83][84][85]He had a turbulent personal life, with numerous bathhouse visits and anonymous pick-ups.[77]Nureyev metErik Bruhn,the celebratedDanishdancer, after Nureyev defected to the West in 1961. Nureyev was a great admirer of Bruhn, having seen filmed performances of the Dane on tour in the Soviet Union with theAmerican Ballet Theatre,although stylistically the two dancers were very different. Bruhn and Nureyev became a couple[83][86]and the two remained together on and off, with a very volatile relationship for 25 years, until Bruhn's death in 1986.[87]

In 1978, Nureyev met the 23-year-old American dancer and classical arts studentRobert Tracy[85]and a two-and-a-half-year love affair began. Tracy later became Nureyev's secretary and live-in companion for over 14 years in a long-term open relationship until death. According to Tracy, Nureyev said that he had a relationship with three women in his life, he had always wanted a son, and once had plans to father one withNastassja Kinski.[62]

Awards and honours

edit| Chevalier of theLegion of Honour (France)[88] |

Commandeur of theOrdre des Arts et des Lettres (France)[89] |

Film, television and musical roles

editIn 1962, Nureyev made his screen debut in a film version ofLes Sylphides.He decided against an acting career to branch into modern dance with theDutch National Ballet[90]in 1968. Nureyev also made his debut in 1962 on network television in America partnered withMaria Tallchiefdancing the pas de deux fromAugust Bournonville'sFlower Festival in GenzanoonThe Bell Telephone Hour.[57][91][92]

In 1972, SirRobert Helpmanninvited him to tour Australia with Nureyev's production ofDon Quixote.[93] In 1973, a film version ofDon Quixotewas directed by Nureyev and Helpmann and features Nureyev asBasilio,Lucette AldousasKitri,Helpmann asDon Quixoteand artists of theAustralian Ballet.

In 1972, Nureyev was a guest inDavid Winters' television specialThe Special London Bridge Special.[94]In 1973 he appeared in a cameo for The Morecambe & Wise Show Christmas Special.

In 1977, Nureyev playedRudolph ValentinoinKen Russell's filmValentino.

In 1978, he appeared as a guest star on the television seriesThe Muppet Show[95]where he danced in a parody called "Swine Lake", sang "Baby, It's Cold Outside"in a sauna duet withMiss Piggy,and sang and tap-danced in the show's finale, "Top Hat, White Tie and Tails".His appearance is credited with makingJim Henson's series become one of the most sought after programs to appear in.[96]

In 1979, Rudolf Nureyev collaborated withStanley Dorfmanto direct a stage and television special performance of Giselle, with music composed byAdolphe Adam.Dorfman also took on the role of producer.[97][98]The ballet was recorded in a studio setting and remains the only filmed performance of the unabridged version featuring Nureyev.[99]Nureyev portrayed the character of Prince Albrecht, whileLynn Seymourtook on the role of Giselle.Monica MasonfromThe Royal Balletperformed as Myrtha, the Queen of the ghostly Wilis. The Ballet of theBavarian State Operaplayed a significant part in the production, and The New World Philharmonic was conducted by David Coleman.[97]

In 1983, he had a non-dancing role in the movieExposedwithNastassja Kinski.

In 1989, he toured the United States and Canada for 24 weeks with a revival of the Broadway musicalThe King and I.

Documentary films

edit- Rudolf Noureev au travail à la barre(Rudolf Noureev Exercising at the Barre) (1970) (4 min 13)[100]

- Nureyev(1981), byThames Television.Includes a candid interview, as well as access to him in the studio.[101]

- Nureyev(1991). Directed by Patricia Foy, the 90-minute documentary chronicles the ups and downs of Nureyev's career, and his professional relationship with Margot Fonteyn, his rumoured depression and his overall effect on modern dance.[102]

- Rudolf Nureyev – As He Is(1991). Directed by Nikolai Boronin, the 47-minute Soviet documentary about Nureyev also includes a long interview with Nureyev during his visit toLeningradin 1990.[103]

- Nureyev: From Russia With Love(2007), by John Bridcut

- Rudolf Nureyev: Rebellious Demon(2012). Directed by Tatyana Malova, the Russian documentary explores the life of Nureyev. The documentary was released on the 80th birth anniversary of Nureyev.[104]

- Rudolf Nureyev – Dance To Freedom(2015), Richard Curson Smith

- Rudolf Nureev. The Island of his Dream(2016) (Russian:Рудольф Нуреев. Остров его мечты, Rudolf Nureyev. Ostrov ego mechty) by Evgeniya Tirdatova

- Nureyev: Lifting the Curtain(2018). Directed by David and Jacqui Morris, the documentary looks into the extraordinary life of Nureyev, with archive interviews and dance sequences.[105]

Posthumous representation

editBallet

edit- Nureyev(2017), a ballet production of theBolshoi Theater,directed byKirill Serebrennikovand Yuri Posokhov. The premiere, scheduled for July 11, 2017, was suddenly canceled by theater directorVladimir Urinthree days before the opening,[106]reportedly by the intervention over "gay propaganda" by Culture MinisterVladimir Medinsky,[107]and finally opened on December 9 and 10, 2017.[108]It was permanently dropped from the theatre's repertroire in April 2023, due to the signing into law ofLGBT censorship.[107]

Books

edit- McCann, Colum(2003).Dancer.Weidenfeld.ISBN978-0-8050-6792-7.Novel based on Nureyev's life.

Film

edit- The White Crow(2018).[109][110]Directed byRalph Fiennes,Oleg Ivenkoplays Nureyev as an adult.[111]The film culminates in his defection at Le Bourget Airport when he was 23 years old. Earlier scenes narrate Nureyev's life: from his birth aboard the train, to childhood lessons in his nativeTatardance, his "ruthless dedication" to the art form, his rigorous training and early ballet performances at the Mariinsky Theater. The film shows his strongindividualisttendency and aloof demeanour, at times appearing arrogant and even cruel.[112]

Music

edit- "Dancing Star",a 2024 song by Englishsynth-popduoPet Shop Boys,recounts Nureyev's life and career.[113]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^/ˈnjʊəriɛf,njʊˈreɪɛf/NURE-ee-ef, nyuurr-AY-ef;Russian:Рудольф Хаметович Нуреев[rʊˈdolʲfxɐˈmʲetəvʲɪtɕnʊˈrʲejɪf];Tatar:Rudolf Xämit ulı Nuriev;Bashkir:Рудольф Хәмит улы Нуриев.

References

edit- ^abLord of the dance – Rudolf Nureyev at the National Film Theatre, London, 1–31 January 2003Archived1 December 2017 at theWayback Machine,by John Percival,The Independent,26 December 2002.

- ^abcRudolf Nureyev, Charismatic Dancer Who Gave Fire to Ballet's Image, Dies at 54Archived10 June 2021 at theWayback Machine,by Jack Anderson,The Independent,7 January 1993.

- ^(in French)Rudolf Noureev exercising at the barreArchived7 August 2017 at theWayback Machine,21 December 1970, site INA (4 min 13).

- ^Philippe Noisette,(in French)« Que reste-t-il de Noureev? »Archived17 August 2016 at theWayback Machine,Les Échos,1 March 2013.

- ^"Rudolf Nureyev: How the dance legend continues to inspire".29 September 2018.Retrieved17 August2024.

- ^Crompton, Sarah (25 September 2018)."'You couldn't take your eyes off him': the triumph and tragedy of Rudolf Nureyev ".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved17 August2024.

- ^Duffy, Martha (18 January 1993)."Two Who Transformed Their Worlds: Rudolf Nureyev (1938-1993)".TIME.Retrieved17 August2024.

- ^Bridcut, John (17 September 2007)."The KGB's long war against Rudolf Nureyev".The Telegraph.London.Archivedfrom the original on 22 March 2016.Retrieved22 May2010.

- ^"Rudolf Nureyev's Choreographies – The Rudolf Nureyev Foundation".Nureyev.org.10 December 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 5 August 2020.Retrieved15 March2020.

- ^Noisette, Philippe (26 January 2013)."Benjamin Millepied, le pari de Stéphane Lissner".Paris Match(in French).Archivedfrom the original on 18 February 2017.

- ^ab"Rudolf Nureyev Foundation official website".Nureyev.org.Archivedfrom the original on 9 February 2019.Retrieved30 August2007.

- ^"Официальный сайт Фонда Рудольф Нуреев".Rudolfnureyev.ru(in Russian). Archived fromthe originalon 17 January 2019.Retrieved26 September2015.

- ^"Rudolf Nureyev's short biography – The Rudolf Nureyev Foundation".Nureyev.org.10 December 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 17 January 2019.Retrieved15 March2020.

- ^"Rudolf Nureyev IBC – Biography".Nureyevibc.Archivedfrom the original on 20 July 2016.Retrieved26 September2015.

- ^Nureyev, Rudolf (1963).Nureyev: an autobiography/Rudolph Nureyev(in Russian). N.Y: E.P. Dutton. p. 233.ISBN978-0-525-16986-4.OCLC869225790.

Original quote: Мать моя родилась в прекрасном древнем городе Казани. Мы мусульмане. Отец родился в небольшой деревушке около Уфы, столицы республики Башкирии. Таким образом, с обеих сторон наша родня — это татары и башкиры....Я не могу точно определить, что значит для меня быть татарином, а не русским, но я в себе ощущаю эту разницу. Наша татарская кровь течет как-то быстрее и готова вскипеть всегда.

- ^"3 Years in the Kirov Theatre".Nureyev.Archived fromthe originalon 16 July 2007.Retrieved20 March2021.

- ^abcdefJohn Bridcut (2007).Nureyev: From Russia With Love(Motion picture). BBC.

- ^"Rudolf Nureyev Foundation official website".Nureyev.org.Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2016.Retrieved30 August2007.

- ^Watson, P., Nureyev: A Biography, p.147

- ^Richard Curson Smith (producer/director) (2015).Rudolf Nureyev – Dance To Freedom.BBC Two(Motion picture).

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.152

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.151

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.161

- ^"The girl who led Nureyev to defect".The Australian.14 December 2015.

- ^(At the time of Nureyev's meeting Bruhn, soloist was the Royal Danish Ballet's highest rank.)

- ^Soutar, Carolyn (2006).The Real Nureyev.St. Martin's Press.ISBN0-312-34097-4.

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.426

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.429

- ^Ballets in which he partnered with Fonteyn.

- ^abAcocella, Joan (8 October 2007)."Wild Thing; Rudolf Nureyev, onstage and off".The New Yorker.Archivedfrom the original on 20 September 2018.Retrieved30 September2018.

- ^"The Royal Ballet's Romeo and Juliet: 50 years of star-crossed dancers – in pictures".The Guardian.2 October 2015.ISSN0261-3077.Archivedfrom the original on 30 September 2018.Retrieved30 September2018.This ballet had been originally created forLynn SeymourandChristopher Gable.

- ^See section "Nureyev and his dance partnerships".

- ^From the archive, 12 July 1967: Charges against ballet stars droppedArchived6 May 2019 at theWayback Machine,The Guardian,12 July 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^Nureyev-His Life by Diane Solway, p. 404

- ^Krebs, Albin;Thomas, Robert McG. Jr.(20 January 1982)."NOTES ON PEOPLE; Austria Adopts Nureyev as One of Its Own".The New York Times.p. 19.Archivedfrom the original on 22 April 2021.Retrieved25 January2021.

- ^"Rudolf Nureyev".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 17 March 2021.Retrieved24 January2021.

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.407

- ^abcd"Nureyev Did Have AIDS, His Doctor Confirms".The New York Times.16 January 1993.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2018.Retrieved18 September2011.

- ^abYaroslav Sedov. Russian Life. Montpelier: Jan/Feb 2006. Vol. 49, Iss. 1; p. 49

- ^"Rudolf Nureyev Foundation official website".Archivedfrom the original on 18 July 2011.Retrieved18 January2011.

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.441

- ^abcdWatson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.455

- ^John Rockwell(13 January 1993)."Rudolf Nureyev Eulogized And Buried in Paris Suburb".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 31 August 2018.Retrieved5 December2009.

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.457

- ^Roslyn Sulcas (11 December 2013)."At a French Museum, Peeks at Nureyev's World".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 17 December 2013.Retrieved16 December2013.

- ^"Legacy Walk unveils five new bronze memorial plaques – 2342 – Gay Lesbian Bi Trans News".Windy City Times.Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2020.Retrieved15 January2016.

- ^Tribute to Rudolf Nureyev – Ballet de l'Opéra de Paris (2012–2013 season)Archived30 April 2021 at theWayback Machine,Homage to Rudolf Noureev, ballet director Brigitte Lefèvre explains why

- ^abMikhail Baryshnikov about Rudolf NureyevArchived11 February 2017 at theWayback Machine,interview with Mikhail Baryshnikov filmed by David Makhateli at Le Palais des Congrès in May 2013, D&D Art Productions (1 min 55)

- ^Speaking to an audience Brigitte Lefèvre and Mikhail Baryshnikov refer to Nureyev as Rudolf.

- ^"В Казани открыли памятник Рудольфу Нуриеву – фоторепортаж".inkazan.ru.7 November 2018.Retrieved19 July2022.

- ^"Рустам Минниханов и Зураб Церетели открыли в Казани памятник Рудольфу Нуриеву".tatar-inform.ru.7 November 2018.Retrieved19 July2022.

- ^"Рустам Минниханов и Зураб Церетели открыли в Казани памятник Рудольфу Нуриеву".protatarstan.ru.7 November 2018.Retrieved19 July2022.

- ^"A chronology by Marilyn J. La Vine".Rudolf Nureyev Foundation. 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 17 January 2019.Retrieved17 January2019.

- ^"Mémoires d'étoiles, Yvette Chauviré".lieurac.Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2018.Retrieved24 July2013.

- ^Rockwell, John (13 January 1993)."Rudolf Nureyev Eulogized And Buried in Paris Suburb".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 9 February 2010.Retrieved7 January2022.

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.283

- ^ab"Danceheritage.org"(PDF).danceheritage.org.Archived(PDF)from the original on 6 September 2015.Retrieved16 December2017.

- ^Rudolf Nureyev, Charismatic Dance Who Gave Fire to Ballet's Image, Dies at 54Archived10 June 2021 at theWayback Machine,The New York Times,7 January 1993

- ^Ruth Page: Early Architect of the American Balletby Joellen A. Meglin on Dance Heritage CoalitionArchived16 September 2013 at theWayback Machine,Danceheritage.org

- ^archives.nypl.org – Ruth Page collectionArchived7 February 2015 at theWayback MachineThe Ruth Page Collection 1918–70at the New York Public Library Archives

- ^Devon Carney, Artistic Director at the Kansas City Ballet, Todd Bolender Center for Dance & Creativity 2013.https://kcballet.org/company/devon-carney/

- ^abEzard, John; Soutar, Carolyn (30 January 2003)."Nureyev and me".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2020.Retrieved19 October2016.

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p. 436

- ^abWatson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,pp. 339–340

- ^abCharles JUDE Artistic Director for the Bordeaux National OperaArchived20 February 2019 at theWayback Machine,site of the Nureyev foundation.

- ^Baryshnikov's tribute to NureyevArchived20 February 2019 at theWayback Machine,the wording of Mikhail Baryshnikov's statement about Rudolf Nureyev, filmed by David Makhateli at Le Palais des Congrès in May 2013, site of the Nureyev foundation.

- ^abMichael Gard (2006). Men who Dance: Aesthetics, Athletics & the Art of Masculinity, New York, Peter Lang Publishing Inc., p. 65.

- ^Sir John Tooley – Nureyev's influence on the development of Ballet in the WestArchived20 February 2019 at theWayback Machine,official site of the Nureyev foundation.

- ^Rudolf Nureyev's childhood in RussiaArchived5 February 2019 at theWayback Machine,citation of Rudolf Nureyev, official site of the Nureyev foundation.

- ^Mikhail BaryshnikovArchived16 January 2021 at theWayback Machine,biography, site of the Kennedy center.

- ^Il était danseur comme les autres. C'est formidable d'avoir 19 sur 20. C'est très rare d'avoir 20 sur 20. Mais, d'avoir 21 sur 20, c'est encore beaucoup plus rare. Et ça, c'était le cas de Noureev. » (original citation of Pierre Bergé).

- ^Obituary in LeSoir France in 1993

- ^« Rudolf Noureev était un TGV. » (original citation of Manuel Legris).

- ^La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballets,documentary film by Frederick Wiseman, 2009.

- ^(in French)Rudolf Noureev, danseur et chorégrapheArchived19 January 2015 at theWayback Machine,review by Kader Belarbi, 6 November 2013, website of the Théâtre du Capitol, Paris, extract: "À côté de lui, il fallait vraiment se surpasser.... À partir de ce moment-là, j'ai commencé à mettre les bouchées doubles." – By his side, you had to surpass oneself.... From this very moment I started stepping on it. (Kader Belarbi, principal dancer with the Paris Opera Ballet when Nureyev was director and chief choreographer).

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.133

- ^abBentley, Toni (2 December 2007)."Nureyev: The Life – Julie Kavanagh – Book Review".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 8 June 2019.Retrieved7 January2022.

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.370

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.369

- ^Watson, P.,Nureyev: A Biography,p.321.

- ^Acocella, Joan (8 October 2007)."Wild Thing".The New Yorker.Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2015.Retrieved23 August2015.

- ^Soutar, Carolyn (27 December 2005).The Real Nureyev: An Intimate Memoir of Ballet's Greatest Hero.New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books. p. 84.ISBN978-0-312-34097-1.Archivedfrom the original on 22 April 2021.Retrieved21 January2016.

- ^abKavanagh, Julie (2007).Rudolph Nureyev: The Life.London; New York: Fig Tree.ISBN978-1-905-49015-8.OCLC77013261.

- ^"TV dance-winner Archambault tackles Nureyev - Arts & Entertainment - CBC News".Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The Canadian Press. 30 November 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2013.Retrieved3 May2012.

- ^abJohn Ezard and Carolyn Soutar (30 January 2003)."Nureyev and me".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2020.Retrieved3 May2012.

- ^"Literary Review".Archived fromthe originalon 22 April 2009.Retrieved13 March2009.

- ^"Rudolf Nureyev Foundation Official Website".Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2019.Retrieved19 March2009.

- ^Rockwell, John (13 January 1993)."Rudolf Nureyev Eulogized And Buried in Paris Suburb".The New York Times.Retrieved25 January2022.

- ^Jennings, Luke (20 December 1992)."Nureyev's Coda".The New Yorker.Retrieved25 January2022.

- ^"Chris Chambers meets Rudi van Dantzig".13 October 2002.Archivedfrom the original on 24 May 2020.Retrieved19 January2020.

- ^Rudolf Nureyev Charismatic Dancer Who Gave Fire to Ballet's Image Dies at 54Archived10 June 2021 at theWayback Machine,The New York Times– Arts Section 7 January 1993

- ^Maria Tallchief, a Dazzling Ballerina and Muse for Balanchine Dies at 88Archived6 February 2018 at theWayback Machine,The New York Times– Dance Section, 12 April 2013

- ^Set and Costume Designs forDon QuixotebyBarry Kayfor both the stage production at the Adelaide Festival (1970) and Nureyev's movie version, gala world premiere at the Sydney Opera House, 1973.

- ^"Lake Havasu city plays a starring role in special".Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph.6 May 1972. p. 12-D.

- ^Garlen, Jennifer C.; Graham, Anissa M. (2009).Kermit Culture: Critical Perspectives on Jim Henson's Muppets.McFarland & Company. p.218.ISBN978-0-7864-4259-1.

- ^McKim, D. W.; Brian Henson."Muppet Central Guides – The Muppet Show: Rudolf Nureyev".Archivedfrom the original on 22 March 2019.Retrieved19 July2009.

- ^ab"Giselle (ITV Ballet, Rudolf Nureyev, Lynn Seymour)".Memorable TV.6 August 2020.Retrieved24 June2023.

- ^"Giselle".TVGuide.Retrieved24 June2023.

- ^"GISELLE – SEYMOUR AND NUREYEV".Fondation Rudolf Noureev.Retrieved24 June2023.

- ^ORTF(21 December 1970)."Rudolf Noureev au travail à la barre".INA(in French).Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2017.Retrieved10 February2017.

- ^Clark, Lester; Catherine, Freeman.After noon plus. Nureyev.U.K.: Thames Television, 1982, 1981.OCLC83489928.

Originally aired on June 17, 1981. Contains an updated introduction by Mavis Nicholson. The profile, titled Nureyev, features interviews with Nureyev recorded in a restaurant and in the studio during a rehearsal for Maurice Béjart's Songs of a wayfarer Chant du compagnon errant.

- ^King, Susan (2 May 1993)."PATRICIA FOY: Keeping Step With Nureyev".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2022.Retrieved7 January2022.

- ^"Фестиваль" Нуреевские сезоны "" Рудольф Нуреев – как он есть ", документальный фильм".meloman.ru.10 November 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2022.Retrieved7 January2022.

- ^"Рудольф Нуреев. Мятежный демон".tatmsk.tatarstan.ru.16 March 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2022.Retrieved7 January2022.

- ^Gleiberman, Owen (18 April 2018)."Film Review: 'Nureyev'".Variety.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2019.Retrieved7 January2022.

- ^"Bolshoi theatre cancels Nureyev ballet premiere".BBC News.8 July 2017.Retrieved19 April2023.

- ^ab"Bolshoy Theater drops 'Nureyev' ballet from repertoire, bending to Russia's anti-LGBT censorship law".Meduza.Retrieved19 April2023.

- ^Нуреев: Балет в двух действиях 18+.Bolshoi Theatre.Archived fromthe originalon 17 June 2021.

- ^Dowd, Vincent (20 March 2019)."White Crow's star dancer 'channelled' Rudolf Nureyev".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 20 March 2019.Retrieved20 March2019.

- ^Vennard, Martin (30 September 2018)."How dance legend Nureyev continues to inspire".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 30 September 2018.Retrieved30 September2018.

- ^Rudolf NureyevatIMDbAccessed 11 April 2019.

- ^Tobias Grey, "Decoding Nureyev's Rebellious Streak" inThe Wall Street Journal,15 April 2019. Interview withDavid HareArchived7 January 2022 at theWayback Machine,author ofThe White Crowscreenplay: quotes; 'white crow' as a "childhood nickname denoting someone who is 'unusual' and 'an outsider'."

- ^Murray, Robin (4 April 2024)."Pet Shop Boys' 'Dancing Star' Is An Ode To Rudolf Nureyev".Clash.Music Republic Ltd.Retrieved10 April2024.

Sources

edit- Nureyev, R.; Bland, A. (1962).Nureyev: An Autobiography with Pictures.London:Hodder & Stoughton.OCLC65776396.

- Percival, J. (1976).Nureyev: Aspects of the Dancer.London:Faber.ISBN0-571-10627-7.OCLC2689702.

- Bland, A. (1977).The Nureyev Valentino: Portrait of a Film.London: Studio Vista.ISBN0-289-70795-1.OCLC3933869.

- Nureyev, R.; Bland A. (1993).Nureyev: His Spectacular Early Years.London:Hodder & Stoughton.ISBN0-340-60042-X.OCLC28496501.

- Watson, P. (1994).Nureyev: A Biography.London:Hodder & Stoughton.ISBN0-340-59615-5.OCLC32162130.

- Kaiser, Charles (1997).The Gay Metropolis: 1940–1996.Houghton Mifflin Company. pp.404 pages.ISBN0-395-65781-4.

- Sokou, R.; Maradei I. (2003).Nureyev-as I knew him.Athens: Kaktos.ISBN960-382-503-4.

- Solway, D. (1998).Nureyev, his life.New York:William Morrow.ISBN0-688-12873-4.OCLC38485934.

- Kavanagh, J. (2007).Rudolph Nureyev: The Life.London; New York: Fig Tree.ISBN978-1-905-49015-8.OCLC77013261.

External links

edit- Website of the Rudolf Nureyev Foundation

- Frank A. Florentine Papers Relating to Rudolf Nureyevat theLibrary of Congress

- Rudolf NureyevatIMDb

- Rudolf Nureyevat theInternet Broadway Database

- Rudolph NureyevFBI Records: The Vault, U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation

Reviews and interviews

edit- "Balanchine-Robbins Work for Nureyev From Moliere; The Casts",The New York Times,Anna Kisselgoff,9 April 1979

- Mikhail Baryshnikov speaks about Rudolf Nureyev,interview by David Makhateli, D&D Art Productions (1 min 55)

- The Boston Phoenixreview of Nureyev'sDon Quixote,1982

- BBC Interviews with Nureyev

- New York Sunreview of PBS's "Nureyev: The Russian Years"Archived16 May 2008 at theWayback Machine

- Lord of the dance – Rudolf Nureyev at the National Film Theatre, London, 1–31 January 2003