You can helpexpand this article with text translated fromthe corresponding articlein Chinese.(January 2022)Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

TheYan'an Sovietwas asovietgoverned by theChinese Communist Party(CCP) during the 1930s and 1940s.[1]In October 1936 it became the final destination of theLong March,and served as the CCP's main base until after theSecond Sino-Japanese War.[2]: 632 After the CCP andKuomintang(KMT) formed theSecond United Frontin 1937, the Yan'an Soviet was officially reconstituted as theShaan–Gan–Ning Border Region(traditional Chinese:Thiểm Cam ninh biên khu;simplified Chinese:Thiểm Cam ninh biên khu;pinyin:Shǎn gān níng Biānqū;Wade–Giles:Shan3-kan1-ning2Pien1-ch'ü1).[a][3]

| Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region Thiểm Cam ninh biên khu | |

|---|---|

| Rump stateof theChinese Soviet Republic | |

| 1937–1950 | |

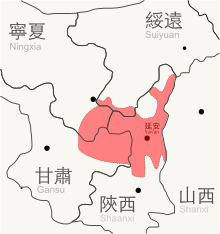

Map of Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region. | |

| Capital | Yan'an(1937–47, 1948–49) Xi'an(1949–50) |

| Area | |

• 1937 | 134,500 km2(51,900 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1937 | 1,500,000 |

| Government | |

| Chairman | |

• 1937–1948 | Lin Boqu |

| Deputy Chairman | |

• 1937–1938 | Zhang Guotao |

• 1938–1945 | Gao Zili |

| Historical era | Chinese Civil War |

• Established | 6 September 1937 |

• Disestablished | 19 January 1950 |

| Today part of | China |

Organization

editThe Shaan-Gan-Ning base area, of which Yan'an was a part, was founded in 1934.[4]: 129

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region became one of a number of border region governments established by the Communists. Other regions included theJin-Sui Border Region(inShanxiandSuiyuan),[b]theJin-Cha-Ji Border Region(in Shanxi,Chahar,andHebei) and theJi-Lu-Yu Border Region(in Hebei,HenanandShandong).

Although not on the front lines of theSecond Sino-Japanese War,the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region was the most politically important and influentialrevolutionary base areadue to its function as thede factocapital of theChinese Communist Revolution.[5]: 129

Economy

editImmediately after setting up the Soviet, the CCP began their "land revolution", confiscating propertyen-massefrom the landlords and gentry of the region.[3]: 265 Its vigour in doing so resulted from two factors, its ideological commitment to peasant revolution and economic necessity. The base area's economic situation was precarious.[4]: 129 ,such that in 1936 the entire Soviet's revenue stood at just 1,904,649 yuan, of which some 652,858 yuan came from confiscation of property.[3]: 266 The program of land redistribution, the party's hostility towards merchants and its ban onopiumdepressed the local economy severely, and by 1936 the Communists were reduced to raiding nearbyShanxi(then ruled by Nationalist-backed warlordYan Xishan) in order to acquire grain and other supplies.[3]: 266 The tightening of the Nationalist blockade in the same year made it difficult to secure resources from outside the region.[4]: 129 At no point during the period 1934-1941 was the Yan'an Soviet financially solvent, being dependent first on the confiscation of property from "enemy classes" and then on Nationalist aid,[3]: 265 the latter of which comprised around 70% of the Soviet's revenue from 1937 to 1940.[3]: 269

The blockade decreased during theSecond United Front,but the Nationalists intensified it after military hostilities began again in 1941.[4]: 129 Japanese assaults in the region and poor harvests worsened the effects of blockade and the region had a severe economic crisis in 1941 and 1942.[4]: 130 By 1944, the region had suffered cumulative inflation of 564,700% since 1937, compared with 75,550% in Nationalist areas.[6]CCP leaders raised the issue of abandoning the area, whichMao Zedongrefused to do.[4]: 130 Mao implemented amass linestrategy,[4]: 130 and imposed heavy taxes on the population in order to pay military expenses, which resulted in what is known as the "Yan'an Way", establishing the Border Region's independence from Nationalist subsidy.[6]However, the economy of the Border Region was also substantially supported by the production and export of opium into Japanese and Nationalist areas,[6]with academicChen Yung-faarguing that the economy of the Border Region was so dependent on opium that, had the CCP not engaged in opium trading, the so-called "Yan'an Way" would have been impossible.

Media

editIn January 1937, American journalistAgnes Smedleyvisited Yan'an.[7]: 165–166 In April,Helen Foster Snowtraveled to Yan'an for research, interviewing Mao and other leaders.[7]: 166

TheEighth Route Armyestablished its first film production group in the Yan'an Soviet during September 1938.[8]: 69

Yuan Muzhiarrived in Yan'an in fall 1938.[4]: 128 With Wu Yinxian, Yuan made a feature-length documentary,Yan'an and the Eighth Route Army,which depicted the Eighth Route Army's combat against the Japanese.[4]: 128 They also filmedNorman Bethuneperforming surgeries close to the front lines.[4]: 128

In 1943, the CCP released their first campaign film,Nanniwan,which sought to develop relationships between the CCP army and local people in the Yan'an area by showcasing the army's production campaign to alleviate material shortages.[4]: 16

In 1944, the CCP welcomed a large group of foreign (primarily American) journalists to Yan'an.[7]: 17 In an effort to contrast the party with the Nationalists, the CCP generally did not censor these foreign reports.[7]: 17 In December 1945, theparty's Central Committeeinstructed the party to facilitate the work of American journalists out of the hope that it would have a progressive influence on American policies toward China.[7]: 17–18

Diplomacy

editAfter the US entry into World War II, the CCP sought military support from the US.[7]: 15 Mao welcomed theAmerican Military Observation Groupin Yan'an and in 1944 invited the US to establish a consulate there.[7]: 15

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^Postal romanization:Shen–Kan–Ning.The name comes from the Chinese abbreviations ofShaanxi,Gansu,andNingxiaprovinces.

- ^Suiyuan is no longer a province, being incorporated intoInner Mongoliain 1954.

Citations

edit- ^"The Yan'an Soviet".18 September 2019.

- ^Van Slyke, Lyman (1986). "The Chinese Communist movement during the Sino-Japanese War 1937–1945". InFairbank, John K.;Feuerwerker, Albert(eds.).Republican China 1912–1949, Part 2.The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. pp. 609–722.doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243384.013.ISBN9781139054805.

- ^abcdefSaich, Tony; Van De Ven, Hans J. (2015-03-04). "The Blooming Poppy under the Red Sun: The Yan'an Way and the Opium Trade".New Perspectives on the Chinese Revolution(0 ed.).Routledge.pp. 263–297.doi:10.4324/9781315702124.ISBN978-1-317-46391-7.OCLC904437646.

- ^abcdefghijkQian, Ying (2024).Revolutionary Becomings: Documentary Media in Twentieth-Century China.New York, NY:Columbia University Press.ISBN9780231204477.

- ^Opper, Marc (2020).People's Wars in China, Malaya, and Vietnam.Ann Arbor:University of Michigan Press.doi:10.3998/mpub.11413902.hdl:20.500.12657/23824.ISBN978-0-472-90125-8.JSTOR10.3998/mpub.11413902.S2CID211359950.

- ^abcMitter, Rana (2013). "Hunger in Henan".China's War with Japan(1 ed.).Penguin Books.pp. 279–280.

- ^abcdefgLi, Hongshan (2024).Fighting on the Cultural Front: U.S.-China Relations in the Cold War.New York, NY:Columbia University Press.doi:10.7312/li--20704.ISBN9780231207058.JSTOR10.7312/li--20704.

- ^Li, Jie (2023).Cinematic Guerillas: Propaganda, Projectionists, and Audiences in Socialist China.Columbia University Press.ISBN9780231206273.