This article has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

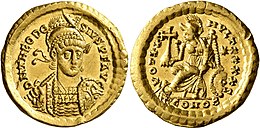

Thesolidus(Latin'solid';pl.:solidi) ornomisma(Greek:νόμισμα,romanized:nómisma,lit. 'coin') was a highly puregold coinissued in theLater Roman EmpireandByzantine Empire.The early 4th century saw the solidus introduced in mintage as a successor to theaureus,which was permanently replaced thereafter by the new coin, whose weight of about 4.5 grams remained relatively constant for seven centuries.

In the Byzantine Empire, the solidus or nomisma remained a highly pure gold coin until the 11th century, when several Byzantine emperors began to strike the coin withless and less gold.The nomisma was finally abolished byAlexios I Komnenosin 1092, who replaced it with thehyperpyron,which also came to be known as a "bezant".The Byzantine solidus also inspired thezolotnikin theKievan Rus'and the originally slightly less puregold dinarfirst issued by theUmayyad Caliphatebeginning in 697.

In Western Europe, the solidus was the main gold coin of commerce from late Roman times toPepin the Short'scurrency reform in the 750s,which introduced thesilver-basedpound-shilling-pennysystem.

In Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the solidus also functioned as a unit of weight equal to1⁄72Roman pound (approximately 4.5 grams).

Solidus as a Roman coin

editThe solidus was initially introduced byDiocletianin small issues and later reintroduced for mass circulation byConstantine the Greatinc. AD 312and was composed of relatively solidgold.[1][2][3]Constantine's solidus was struck at a rate of 72 to aRoman pound(of about 326.6 g) of gold; each coin weighed 24 Greco-Romancarats (189 mg each),[4]or about 4.5 grams of gold per coin. By this time, the solidus was worth 275,000 increasingly debaseddenarii,each denarius containing just 5% (or one twentieth) of the amount of silver it had three and a half centuries beforehand.[5]With the exception of the early issues of Constantine the Great and the odd usurpers, the solidus today is a much more affordable gold Roman coin to collect, compared to the older aureus, especially those of Valens, Honorius and later Byzantine issues.

In the Byzantine period

editThe solidus was maintained essentially unaltered in weight, dimensions and purity, until the 10th century. During the 6th and 7th centuries "lightweight" solidi of 20, 22 or 23siliquae(onesiliquawas 1/24 of a solidus) were struck along with the standard weight issues, presumably for trade purposes or to pay tribute. The lightweight solidi were especially popular in the West, and many of these lightweight coins have been found in Europe, Russia and Georgia. The lightweight solidi were distinguished by different markings on the coin, usually in theexerguefor the 20 and 22siliquaecoins, and by stars in the field for the 23siliquaecoins.

Despite the Eastern half of the Roman Empire being predominantlyGreekspeaking, the words on the coinage continued to be struck in Latin well into the eighth century. The letters on the coinage began to lose theirClassical Latinlook under the emperorHeraclius,but until the reign ofConstantine VIthe coins continued to feature Latin text, being finally replaced with Greek script in the early years of the ninth century.

In theory, the solidus was struck from pure gold, but because of the limits of refining techniques, in practice – the coins were often about 23k fine (95.8% gold). In the Greek-speaking world during the Roman period, and then in theByzantine economy,the solidus was known as the νόμισμα (nomisma,pluralnomismata).[4]In the 10th century Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas (963–969) introduced a new lightweight gold coin called thetetarteron nomismathat circulated alongside the solidus, and from that time the solidus (nomisma) became known as the ἱστάμενον νόμισμα (histamenon nomisma), in the Greek speaking world. Initially it was difficult to distinguish the two coins, as they had the same design, dimensions and purity, and there were no marks of value to distinguish the denominations. The only difference was the weight. Thetetarteronnomismawas a lighter coin, about 4.05 grams, reminiscent of the lightweight solidi of the 6th and 7th centuries, but thehistamenon nomismamaintained the traditional weight of 4.5 grams. To eliminate confusion between the two, from the reign of Basil II (975–1025) the solidus (histamenon nomisma) was struck as a thinner coin with a larger diameter but with the same weight and purity as before. From the middle of the 11th century, the larger diameterhistamenon nomismawas struck on a concave (cup-shaped) flan, while the smallertetarteron nomismacontinued to be struck on a smaller flat flan.

Debasement, decline, and elimination of the solidus

editWhen the former money changerMichael IV the Paphlagonian(1034–41) assumed the imperial throne in 1034, he began the slow process of debasing both thetetarteron nomismaand thehistamenon nomisma.The debasement was gradual at first, but then accelerated rapidly: about 21 carats (87.5% pure) during the reign ofConstantine IX Monomachos(1042–1055), 18 carats (75%) underConstantine X Doukas(1059–1067), and 16 carats (66.7%) underRomanos IV Diogenes(1068–1071). After Romanos lost the disastrousBattle of Manzikertto the Turks, the empire's ability to generate revenue deteriorated further and the solidus continued to be debased. The coin's purity reached 14 carats (58%) underMichael VII Doukas(1071–1078), 8 carats (33%) underNikephoros III Botaneiates(1078–1081) and 0 to 8 carats during the first eleven years of the reign ofAlexios I Komnenos(1081–1118). Alexios reformed the coinage in 1092 and eliminated the solidus (histamenon nomisma) altogether. In its place he introduced a new gold coin called thehyperpyronnomismaat about 20.5k fine (85%). The weight, dimensions and purity of thehyperpyron nomismaremained stable until theSack of Constantinopleby the Crusaders in 1204. After that time the exiled Empire of Nicea continued to strike a debasedhyperpyron nomisma.Michael VIII Palaiologosrecaptured Constantinople in 1261, and under him the restored Byzantine Empire continued to strike the debasedhyperpyron nomismauntil the joint reign ofJohn V Palaiologosand John VI (1347–1354), who struck the final Byzantine gold coins. After that time thehyperpyron nomismacontinued as a unit of account, but it was no longer struck in gold.

Mints across the empire

editFrom the 4th to the 11th centuries,solidiwere minted mostly at theConstantinoplemint. However, certain branch mints were active producers of solidi. In theRoman Empireduring the 4th century,Trier,Rome,Milan,andRavennawere the main producers of gold coins in the West, while Constantinople,Antioch,Thessalonica,andNicomediastruck gold coins in the East. The Germanic invasions of the early fifth century led to the closure of many provincial mints, and by 410 the only mints that struck gold solidi were Rome, Ravenna, Constantinople, and Thessalonica. TheFall of the Western Roman Empirein 476 saw the end of official Roman coinage in the West, though Germanic successor kingdoms such as theOstrogothic Kingdomand theFrankscontinued to strike imitative solidi, with the portrait and title of the emperor in Constantinople.

Justinian I'sreconquests in the Western Empire reopened several mints, which began to strike gold solidi. His reconquest of theVandal Kingdomreopened the mint atCarthage,where a great number of solidi were struck. In the early seventh century, the mint at Carthage began to strike small "globular" solidi, about half the size of a normal solidus but much thicker. These "globular" solidi were only struck in Carthage, and the mint continued to produce great quantities of solidi until its conquest by the Arabs in 698. Justinian's conquests also allowed for imperial mints to begin coining solidi in Italy, with the mints at Ravenna and Rome once again striking official Roman coins. Under Justinian, Antioch in Syria started to mint solidi again after a 150-year hiatus, and a few solidi were struck atAlexandriain Egypt, though these are very rare today.

The mint at Syracuse grew beginning in the mid-seventh century during the reign ofConstans II,who briefly moved the empire's capital to the city. During the 8th and 9th centuries, the Syracuse mint produced a large number ofsolidithat failed to meet the specifications of the coins produced by the imperial mint in Constantinople. The Syracusesolidiwere generally lighter (about 3.8g) and only 19k fine (79% pure).

Although imperial law forbade merchants from exporting solidi outside imperial territory, this was very loosely enforced, and many solidi have been found in Russia, Central Europe, Georgia, and Syria. In particular, it seems as if the light-weight solidi were meant for foreign trade. In the 7th century they became a desirable circulating currency in Arabian countries. Since the solidi circulating outside the empire were not used to pay taxes to the emperor, they did not get reminted, and the soft pure-gold coins quickly became worn.[4]

Through the end of the 7th century, Arabian copies of solidi –dinarsminted by the caliphAbd al-Malik ibn Marwan,who had access to supplies of gold from theupper Nile– began to circulate in areas outside the Byzantine Empire. These corresponded in weight to only 20 carats (4.0 g), but matched the weight of the lightweight (20siliquae) solidi that were circulating in those areas. The two coins circulated together in these areas for a time.[4]

The solidus was not marked with any face value throughout its seven-century manufacture and circulation. Fractions of the solidus known assemissis(half-solidi) andtremissis(one-third solidi) were also produced. The fractional gold coins were especially popular in the West where the economy had been significantly simplified and few purchases required a denomination so large as the solidus.

The wordsoldieris ultimately derived fromsolidus,referring to the solidi with which soldiers were paid.[6]

Impact on world currencies

editIn medieval Europe, where the only coin in circulation was the silver penny (denier), the solidus was used as a unit of account equal to 12deniers.Variations on the wordsolidusin the local language gave rise to a number of currency units:

France

editIn the French language, which evolved directly from common orvulgar Latinover the centuries,soliduschanged tosoldus,thensolt,thensoland finallysou.No goldsolidiwere minted after theCarolingiansadopted the silver standard. Thenceforward, thesolidusorsolwas a paper accounting unit equivalent to one-twentieth of a pound (librumorlivre) of silver and divided into 12denariiordeniers.[7]The monetary unit disappeared with decimalisation and introduction of thefrancby theFrench First Republicduring theFrench Revolutionin 1795, but the coin of 5 centimes, a twentieth part of the franc, inherited the name "sou" as a nickname: in the first half of the 20th century, a coin or an amount of 5 francs was still often referred to ascent sous.

To this day, in French around the world,soldemeans thebalanceof an account or invoice, or sales (seasonal rebate), and is the specific name of asoldier'ssalary.Although thesouas a coin disappeared more than two centuries ago, the word is still used as a synonym of money in many French phrases:avoir des sousis being rich,être sans un souis being poor (same construction as "penniless" ).

Quebec

editIn Canadian French,souandsou noirare commonly employed terms for theCanadian cent.Cenneandcenne noireare also regularly used. The European Frenchcentimeis not used in Quebec. In Canada one hundredth of adollaris officially known as a cent (pronounced /sɛnt/) in both English and French. However, in practice, a feminine form ofcent,cenne(pronounced /sɛn/) has mostly replaced the official "cent"outside bilingual areas. Spoken use of the official masculine form of cent is uncommon in francophone-only areas of Canada.Quarter dollar coinsin colloquial Quebec French are sometimes calledtrente-sous(thirty cents), because of a series of changes in terminology, currencies, and exchange rates. After the British conquest ofCanadain 1759, French coins gradually fell out of use, andsoubecame a nickname for thehalfpenny,which was similar in value to the Frenchsou.Spanish pesos and U.S. dollars were also in use, and from 1841 to 1858 the exchange rate was fixed at $4 = £1 (or 400¢ = 240d). This made 25¢ equal to 15d, or 30 halfpence i.e.trente sous.In 1858, pounds, shillings, and pence were abolished in favour of dollars and cents, and the nicknamesoubegan to be used for the1¢ coin,but the termun trente-sousfor a 25¢ coin has endured.[8] In the vernacular Quebec Frenchsousandcennesare also frequently used to refer to money in general, especially small amounts.

Italy

editThe name of the medieval Italian silversoldo(pluralsoldi), coined since the 11th century, was derived fromsolidus.

This word is still in common use today in Italy in its pluralsoldiwith the same meaning as the English equivalent "money". The wordsaldo,like the Frenchsoldementioned above, means the balance of an account or invoice; the GermanSaldois a loan word with the same meaning.[9]It also means "seasonal rebate".[citation needed]

Switzerland

editIn the Italian speaking regions, the word "soldo", on top of its modern uses in Italian, is still currently used in its archaic meaning: the pay soldiers receive, this is also true in French speaking Switzerland, where Swiss soldiers will receive "il soldo" – "la solde"; and German speaking Switzerland, where it is "der Sold".

In Italian the verb Soldare (Assoldare) means hiring, more often soldiers (Soldati) or mercenaries, deriving exactly from the use of the word as described above.

Spain and Peru, Portugal and Brazil

editAs withsoldierin English, the Spanish and Portuguese equivalent issoldado(almost the samepronunciation). The name of the medievalSpanishsueldoand Portuguesesoldo(which also means salary) were derived fromsolidus;the termsweldoin most Philippine languages (Tagalog,Cebuano,etc.) is derived from the Spanish.

The Spanish and Portuguese wordsaldo,like the Frenchsolde,means the balance of an account or invoice. It is also used in some other languages, such as German and Afrikaans.

Some have suggested that the Peruvian unit of currency, thesol,is derived fromsolidus,but the standard unit of Peruvian currency was therealuntil 1863. Throughout the Spanish world the dollar equivalent was 8 reales ( "pieces of eight" ), which circulated legally in the United States until 1857. In the US, the colloquial expression "two bits" for a quarter dollar, and the stock market currencyreallast used for accounting, traded in1⁄8of a U.S. dollar until 2001, still echoes the legal usage in the US in the 19th century.

The Peruviansolwas introduced at a rate of 5.25 per British Pound, or just under four shillings (the legacysoldus). The termsoles de orowas introduced in 1933, three years after Peru had actually abandoned the gold standard. In 1985 the Peruvian sol was replaced at one thousand to one by theinti,representing the sun god of the Incas. By 1991 it had to be replaced with a newsolat a million to one, after which it remained reasonably stable.

United Kingdom

editKingOffa of Merciabegan mintingsilver pennieson theCarolingian systemc. 785.As on the continent, English coinage was restricted for centuries to the penny, while thescilling,understood to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere,[10]was merely aunit of accountequivalent to 12 pence. TheTudorsminted the first shilling coins. Prior todecimalisationin the United Kingdom in 1971, the abbreviations.(fromsolidus) was used to representshillings,just asd.(denarius) and£(libra) were used to representpenceandpoundsrespectively.

Under the influence of the oldlong S⟨ſ⟩,[citation needed]the abbreviations "£sd"eventually developed into the use of aslash⟨/⟩,which gave rise to that symbol's ISO and Unicode name "solidus".

Vietnam

editThe French termsouwas borrowed intoVietnameseas the wordxu(Chinese:Xu).[11]The term is usually used to simply mean the word "coin" often in compound in the forms ofđồng xu(Đồng xu) ortiền xu(Tiền xu). The modernVietnamese đồngis nominally divided into 100xu.

See also

edit- RomanandByzantine coinage

- Bezant

- Hoxne Hoard

- Solidusandslashpunctuation marks

References

editNotes

edit- ^Mattingly, Harold (1946)."The Monetary Systems of the Roman Empire from Diocletian to Theodosius I".The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society.Sixth Series.6(3/4): 111–120.JSTOR42663245.

- ^Spufford, Peter (1988).Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe.Cambridge University Press. p. 398.ISBN9780521375900.

- ^Jones, A. H. M. (1953)."Inflation under the Roman Empire".The Economic History Review.New Series.5(3): 293–318.doi:10.2307/2591810.JSTOR2591810.

- ^abcdPorteous 1969

- ^"Reproduction Solidus".Dorchesters Reproduction Coins & Medals.

- ^"Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary".Merriam-Webster.Retrieved2008-12-05.

- ^Spufford, Peter (1993).Money and its use in medieval Europe.Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–9, 18–19, 25, 33–35, 37, 50–52, 397, 400.ISBN978-0-521-37590-0.

- ^Frédéric Farid (26 September 2008)."Pourquoi trente sous = 25 cents?".Retrieved6 October2010.

- ^"Saldo".Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache(in German).RetrievedDecember 17,2021.

- ^Hodgkin, Thomas (1906).The history of England… to the Norman conquest.London, New York and Bombay: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 234.ISBN9780722222454.

- ^"Soạn bài Thực hành Tiếng Việt bài 3 SGK Ngữ văn 6 tập 1 Cánh diều chi tiết | Soạn văn 6 – Cánh diều chi tiết".loigiaihay(in Vietnamese).RetrievedJan 14,2023.

Bibliography

edit- Porteous, John (1969)."The Imperial Foundations".Coins in history: a survey of coinage from the reform of Diocletian to the Latin Monetary Union.Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp.14–33.ISBN0-297-17854-7.

External links

edit- Media related toSolidusat Wikimedia Commons

- Online numismatic exhibit: "This round gold is but the image of the rounder globe" (H.Melville). The charm of gold in ancient coinage

- .Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). 1911.